64 www.mca-marines.org/gazette

Marine Corps Gazette • December 2015

Ideas & Issues (Performance eva luat Io n system)

S

election boards rely heavily on

fitness report relative values to

assess performance, but these

numbers are poorly understood

and widely misinterpreted—even by

subject matter experts.

1

For example,

in this journal, the head of Policy

and Compliance for the Performance

Evaluation System claimed that relative

values “take the guesswork out of rank-

ing Marines;” the staff of the Officer

Assignments Branch wrote that values

above 90 reflect “above average perfor-

mance;” and an article by a member of

a promotion board wrote that relative

values place Marines on a “bell curve.”

2

Similar statements appear in official

publications. Until February 2015, the

order governing the Performance Evalu-

ation System (the PES Manual) said “a

relative value of 80 indicates the report

has the lowest fitness report average of

any report written by the RS [reporting

senior] on a Marine of that grade,” and

the student handout on fitness reports

at The Basic School has long taught

new officers that relative values place

Marines on a bell curve to “guarantee

consistent evaluation.”

3

All these statements are either wrong

or highly misleading. As we show below,

a relative value does not place Marines

on a bell curve, nor does a value of 80

mean a report is the lowest report in

the RS’s profile, nor does it take the

guesswork out of ranking Marines.

More importantly, we show that rela-

tive values are an unreliable measure of

relative performance that often change

an RS’s evaluation—sometimes in ways

that selection boards cannot currently

detect. The use of relative values there-

fore increases the odds that selection

boards will make mistakes, and the

Marine Corps should abandon them

in favor of simpler metrics.

In this article, we first review the

importance of relative values in the se-

lection board process. Then we show

both why relative values cannot be

properly interpreted with the tools se-

lection boards currently use and how

to correct the problem. Following some

concluding remarks, we include a short

appendix that presents the mathemati-

cal equation for relative value and pro-

vides a detailed explanation of how the

number is calculated.

The Importance of Relative Values

Consistently high relative values do

not guarantee a Marine will be retained

or promoted, nor do consistently low

relative values guarantee a short career.

Past board members we talked to have

seen Marines with very high relative

values get passed over and Marines with

comparatively low relative values select-

ed with enthusiasm. Our impression,

based on both interviews and general

observation, is that the Marine Corps

does a reasonably good job of assessing

the entirety of a Marine’s record when

making selection decisions and does not

place excessive weight on relative values.

Still, relative values shape the way

boards view Marines and affect the

overall probability of selection. After-

action surveys from the Fiscal Year

2015 Sergeant Major Through Master

Sergeant Selection Board and the Fis-

cal Year 2014 Staff Sergeant Selection

Board reveal that a large majority of

board members thought relative val-

ues were of equal or greater importance

than the narrative comments in a fitness

report (in part because most narrative

comments have to be neutral or positive

or the report will be rendered adverse).

Members of the Sergeant Major through

Master Sergeant Board said relative

values “set the tone,” and the narrative

comments “would either confirm the

RV or slightly improve the perception

of the RV … in cases of extreme ambi-

guity.” They emphasized that while the

relative value was only one tool among

many, “it did give the briefer a good

Miscalculating

Performance

How relative values work,

and why the Marine Corps should stop using them

by Maj Ryan T. Baker, USMCR & Capt Yuk Wing Kwan

>Maj Baker is a 3002 supply officer. He spent five years on active duty before

transferring to the Reserves to start graduate school. While on active duty, he

deployed twice with 2d Battalion, 5th Marines: once in support of Operation

Iraqi Freedom and once with the 15th MEU. He is currently the airfield opera-

tions company commander for MWSS-472 and a full-time PhD candidate at

George Washington University.

>>Capt Kwan is an 0402 logistics officer. He has a combined 15 years of enlisted

and officer experience, including a combat deployment in support of Operation

Enduring Freedom with 1st MarDiv. Capt Kwan is currently the integrated active

duty officer-in-charge for MWSS-472.

www.mca-marines.org/gazette 65Marine Corps Gazette • December 2015

snapshot of where the Marine actually

stood.” Briefers from both boards also

said that the master brief sheet and fit-

ness reports were the two most helpful

documents for representing a Marine

to the board.

4

Exactly how much influence relative

values have varies from board to board

(they appear to have been less influential

on the staff sergeant board discussed

above, for example), but they are im-

portant more often than not. Using of-

ficial Marine Corps data, students at the

Naval Postgraduate School have found

that relative values affect the probability

of officer promotion even when control-

ling for a host of other variables like

PME completion, combat experience,

personal awards, time in grade, civilian

education, commissioning source, PFT

score, occupational field, command

billets, and reviewing officer marks,

among other things.

5

One of these

studies estimated that a captain with

an average cumulative relative value of

92 is about 4.5 percentage points more

likely to be selected for promotion than

a captain with an average cumulative

relative value of 88, even when con-

trolling for all the factors listed above.

While this effect is smaller than the

estimated effect of PME completion,

it is larger than adding an additional

personal award to a Marine’s file.

6

Some Problems with Relative Values

Figure 1 provides an overview of how

relative values are calculated (for a more

complete explanation, see the short ap-

pendix at the end of this article). For

the relative value to be a reliable sum-

mary of relative performance, RSs must

have observed a mix of strong and weak

performers, and those Marines must be

split symmetrically on either side of the

profile average.

7

Observing both strong

and weak performers ensures that the

difference between 80 and 100 corre-

sponds to a meaningful difference in

performance. Symmetry is required be-

cause the relative value is derived from

the mean average, which is informative

when summarizing symmetrical dis-

tributions but often misleading when

distributions are skewed.

8

Assuming

RSs are marking their reports in accor-

dance with the PES Manual, both the

symmetry and the performance spread

of their profiles is determined by the

mix of Marines they have observed. For

example, an RS may have had one good

Marine and several average Marines, or

one bad Marine and several excellent

ones, or several very similar Marines, or

four very good ones and two very bad

ones, or some similar combination. In

such cases, the accuracy of the relative

value will be degraded.

Figure 2 shows just how poorly rela-

tive values sometimes capture relative

performance. The figure shows four

possible RS profiles, each of which has

the same profile average and the same

highest report. Within these profiles,

the report average and the relative value

of the highlighted reports is also exactly

the same. Notice that the rank of the

highlighted report is different in each

profile. In profile one, the highlighted

report is ranked third of six; in profile

four, the report with the same average

and same relative value is sixth of six.

These reports suggest very different rela-

tive performance, but since these two

profiles have exactly the same summary

statistics, they are indistinguishable

on a master brief sheet.

9

They are also

indistinguishable to a selection board

because selection boards do not consider

the position of a report in the RS profile,

only the relative value (we confirmed

this through interviews with members

of past promotion boards).

In addition to the raw relative values,

selection boards are also interested in

which “third” of the relative value scale

a report falls. Reports with a relative

value between 80.00 and 86.66 are con-

sidered bottom third; those between

86.67 and 93.33 are middle third; and

those between 93.34 and 100.00 are top

third.

10

The assumption is that Marines

with reports consistently in the top third

are better performers than Marines with

reports consistently in the bottom third,

but this assumption does not always

hold true. Note that even though each

highlighted report in Figure 2 falls in a

different place in each RS profile, they

will all be in the middle third from the

point of view of a selection board.

11

This can be a blessing or a curse.

For the Marine ranked sixth of six

in Figure 2, it is certainly a blessing,

since selection boards will not know

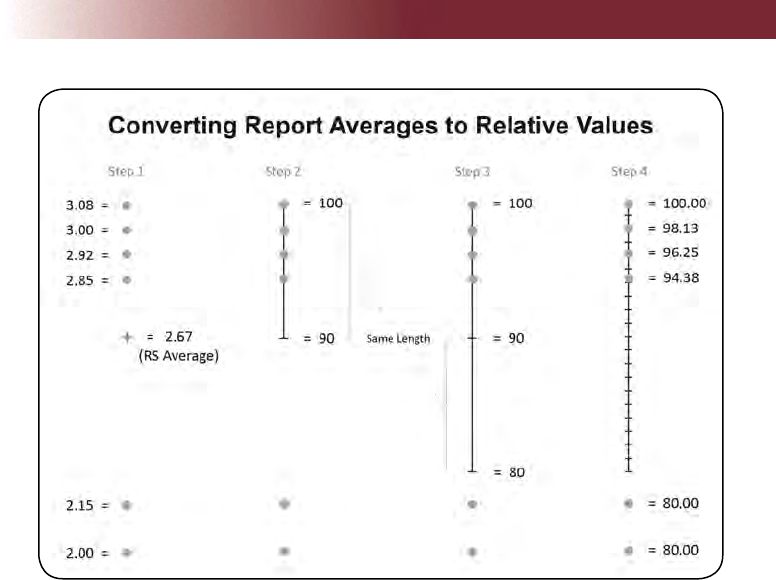

Figure 1. This figure shows how relative value is calculated using a hypothetical RS profile

with six reports. The numbers on the far left are fitness report averages; those on the far

right are relative values. Each dot represents one fitness report in the RS profile.

Note the absence of a bell curve, the fact that a relative value of 80 does not mean the report

is the lowest in the profile, and that no Marines fall in the middle third

(we discuss thirds in more detail later).

66 www.mca-marines.org/gazette

Marine Corps Gazette • December 2015

Ideas & Issues (Performance eva luat Io n system)

that the RS actually ranked them in

the bottom third of the Marines they

observed (by quantile). But the process

can also work in reverse: a Marine with

the second highest report a RS has ever

written can also fall into the bottom

third. This means relative values can

effectively change the evaluation of an

RS. If, for example, the RS in profile

four intentionally ranked the Marine

last to communicate to the board the

Marine is a below average performer,

the board’s reliance on relative values

will instead lead them to see a “middle

third” Marine.

Another important feature of relative

values is that they can magnify small

differences in fitness reports. When a

RS has written only three reports, it is

possible for the smallest change in one

attribute mark to be the only difference

between a report with a relative value

of 100 and one with an 85 (top third

versus bottom third). This happens

when changing a single mark can pro-

duce a tie with either of the other two

reports in the RS profile—a situation

not unlikely when an RS has written

multiple reports on the same Marine

or has multiple Marines with similar

performance.

12

More generally, unless

all reports in the profile have the same

average, there will always be at least

one with a relative value of 100, and

always at least one below 90, even if

the performance of the Marines in the

RS’s profile was very similar.

13

How to Fix It

Except by chance, most relative

values cannot be properly interpreted

without referencing the RS profiles from

which they are derived.

14

Consequently,

selection boards must either find a way

to actively consult RS profiles during

their deliberations, change the way rela-

tive values are calculated, or abandon

the use of relative values altogether. This

give the Marine Corps several options:

one approach would be to add a copy of

all the relevant RS profiles to the stack

of material each board must review, and

then charge them with interpreting the

relative values and the RS profiles in re-

lation to one another. Another approach

would be to reformat the master brief

sheet to show graphically where each

Marine falls within the distribution of

reports in the RS profile (perhaps us-

ing a “box-and-whisker” plot that splits

profiles into thirds). Still another ap-

proach would be to change the equation

for relative value so that it becomes a

nonparametric statistic.

However, we think the best solu-

tion is for selection boards to abandon

relative values entirely, and instead

use raw RS profiles and a Marine’s

rank within them. This solution is

not perfect, but it solves the current

problem and has important virtues: it

allows for the calculation of thirds in a

more meaningful way (using quantiles,

similar to the way class standing works

at The Basic School), it requires the

least training and effort to implement,

and it is by far the most straightfor-

ward conceptually. Put simply, Ma-

rines intuitively understand the RS

profile and ranking in a way they do

not understand relative values, which

increases the odds that fitness reports

will be interpreted with due skepticism

by selection boards.

Until the Marine Corps comes

around to this view, we strongly recom-

mend RSs track their profile carefully

and write reports to achieve a specific

relative value, since it is the only way

for an RS to ensure that a selection

board will accurately interpret their

evaluation.

15

The PES Manual explic-

itly forbids this practice, but we believe

this restriction undermines rather than

upholds the Commandant’s intent for

the Performance Evaluation System.

16

At the moment, the Marine Corps does

not provide a way for RSs to determine

the relative value of a report before it is

processed, or a way to look up the rela-

tive values of reports they have already

written (the relative value appears only

on the MRO’s master brief sheet). To

help RSs track their reports, we have

created a free “FitRep Tracker” that cal-

culates cumulative relative values and

posted it online at https://sites.google.

com/site/bakerryant/research (the file

cannot be downloaded using a Marine

Corps computer, unfortunately). We

encourage RSs to either use this or some

similar tool while they are writing their

fitness reports.

Conclusion

Relative values are not the only thing

that determines whether a Marine is

selected by a board, but they are im-

portant enough that we should care

Figure 2. This table shows four possible RS profiles (the numbers are fitness report aver-

ages). The highlighted reports all have a report average of 3.00 and a relative value of 86.67.

The RS average and RS high are also the same in each profile. The position of the report in

the RS’s distribution varies with the value of the other reports in the profile.

www.mca-marines.org/gazette 67Marine Corps Gazette • December 2015

whether they are interpreted accurately.

As it stands, few Marines understand

how to properly interpret relative val-

ues even among those that are trained

to know. If they did, selection boards

would actively consult RS profiles dur-

ing their deliberations, since that is the

only way to make the number useful

in the way the Marine Corps wants it

to be. This article was written as a first

step toward correcting this problem,

but even if it succeeds, relative values

will still obscure more than they clarify.

Their continued use degrades the ability

of selection boards to meet the demands

of their precept and the Commandant’s

intent, and they should be discarded in

favor of a simpler and more transparent

alternative.

Appendix: How Relative Value is Cal-

culated

Every observed fitness report has a

numerical average based on the values of

the attribute marks in the report. This

average is called a “fitness report aver-

age,” (FRA, or just “report average”),

and it is calculated much the same way

a grade-point average is calculated in

high school. An ‘A’ is assigned a value

of one, a ‘B’ gets a value of two, and so

on up to ‘G,’ which gets a value of seven

(attributes marked “not observed” are

not assigned a value and are excluded

from the calculation). These numbers

are added together and then divided

by the total number of observed attri-

butes to get the report average, which

will always fall somewhere between one

and seven. The collection of all report

averages an RS has written on Marines

of the same rank is called the “RS pro-

file” for that rank.

17

Once a profile has

at least three reports in it, the system

will calculate relative values for each

report.

18

To convert report averages into rela-

tive values takes several steps, and it

will probably help to review Figure 1

as we walk through them. First, the

system calculates the average report

average (i.e., the average FRA) in the

RS profile and assigns it a relative value

of 90 (note that we are now working

with averages on two different levels,

one for the individual reports and one

for the profile as a whole). The highest

report average (or averages, if there is

a tie) is always assigned a relative value

of 100. The only exception is when all

the reports in a profile have the same

average, in which case all are assigned a

value of 90. In every other case, reports

with averages above the profile average

will receive relative values above 90, and

reports with report averages below the

profile average will receive values be-

low 90. Next, the report average for the

highest report (the one with a value of

100) is subtracted from the average of

the report averages (the number that

represents a value of 90). This gives

the “distance” between 100 and 90 on

the relative value scale. This distance is

then duplicated below 90, producing a

symmetrical scale from 80 to 100. Note

that this scale changes over time, since

each new fitness report will normally

change the average of the RS’s profile.

To track this change, both the relative

value at the time of processing and the

cumulative relative value are tracked

on the Marine-reported-on’s (MRO’s)

master brief sheet.

To figure out where an individual

report falls on this scale, the “distance”

of an individual report from the profile

average is compared to the “distance”

from the profile average to the high-

est report average (or to 80, the math

is the same in either case because the

scale is symmetrical). If an above aver-

age report is 90 percent of the distance

from the profile average to the highest

report average, that report is assigned a

relative value of 99. If a below average

report is 40 percent of the distance from

the profile average to the value of 80,

that report is assigned a relative value of

86. It is possible for report averages to

fall below 80 in this calculation. When

this happens, the system automatically

changes the relative value to 80 (this

means several reports toward the bot-

tom of the profile may be assigned a

relative value of 80 even if they are not

the lowest-ranked report in the profile).

Also note that because the relative value

is based on the average and the high-

est report, it is possible for the lowest

report in the profile to have a value sig-

nificantly higher than 80.

19

Figure 3

shows the full mathematical equation

for relative value.

Notes

1. Relative values range from 80 to 100 based

on how far above or below average a report’s

attribute marks are when compared to other

reports written by the same reporting senior

(RS) on Marines of the same rank. They were

devised to help selection boards “level the play-

ing field” by giving them a way to objectively

compare reports written by RSs with different

grading philosophies. See U.S. Marine Corps,

Performance Evaluation System, MCO P1610.7,

(Feb 13, 2015) (hereafter “PES Manual”), 8-5f;

Manpower Management Support Branch-30,

“New Reporting Official PES Brief,” (December

Figure 3. The mathematical equation for relative value.

68 www.mca-marines.org/gazette

Marine Corps Gazette • December 2015

Ideas & Issues (Performance eva luat Io n system)

4, 2014), 69. For a detailed explanation of how

they are calculated, see this article’s appendix.

2. CWO4 Shelby Zimmerman, “Writing Fit-

ness Reports: A Guide,” Marine Corps Gazette,

(Quantico, VA: January 2012): 75; MMOA

Staff, “Your Next Assignment: Officer Career

Advice from MMOA,” Marine Corps Gazette,

(Quantico, VA: August 2009): 68; LtCol

Eugene “Pete” Wittkoff, MSgt Jeremy Rich,

and GySgt Samuel O. Carter, “Performance

Evaluation System: Really Taking Care of Our

Marines,” Marine Corps Gazette, (Quantico,

VA: December 2012): DE12.

3. U.S. Marine Corps, MCO P1610.7F, Perfor-

mance Evaluation System, Chapter 2 (Nov 19,

2010), G-3; The Basic School, “Fitness Reports

B3K3738 Student Handout,” (August 2014),

6. Earlier versions of the TBS student handout

contain the same information.

4. Enlisted Career Counselor and Evaluation

Unit, FY 2015 SGTMAJ Through MSGT Selec-

tion Board Survey, ed. GySgt Trevor L. Goff

(n.d.). Enlisted Career Counselor and Evalua

tion Unit, FY2014 Staff Sergeant Selection Board

Survey, ed. GySgt Trevor L. Goff (n.d.).

5. Joel Hoffman, “Significant Factors in Predict-

ing Promotion to Major, Lieutenant Colonel,

and Colonel in the United States Marine Corps”

(master’s thesis, Naval Postgraduate School,

2008); See also Jacob L. Reynolds, “Effect of

Being an Aviator on Promotion to O-5 in the

USMC” (master’s thesis, Naval Postgraduate

School, 2011); Raul P. Garza, “United States

Marine Corps Career Designation Board:

Significant Factors in Predicting Selection”

(master’s thesis, Naval Postgraduate School,

2014); Shannon Phillips and Adam Clemens,

The Fitness Report System for Marine Officers:

Prior Research (Arlington, VA: Center for Naval

Analyses, 2010). These studies are imperfect,

but they represent the best estimates publicly

available. We requested data from Records and

Performance Branch (MMRP) to do our own

analysis, but they did not have the resources to

support our request.

6. The size of the effect appears to vary sub-

stantially with rank. See Hoffman, “Signifi-

cant Factors in Predicting Promotion to Major,

Lieutenant Colonel, and Colonel in the United

States Marine Corps,” 87–126.

7. We only have space to review a few of the

problems with relative values here. For more

information, we recommend Adam Clemens,

Lauren Malone, Shannon Phillips, Gary Lee,

Cathy Hiatt, and Theresa Kimble, An Evalua-

tion of the Fitness Report System for Marine Of-

ficers (Arlington, VA: Center for Naval Analyses,

2012); Capt Barrett P. Dupuy, “Performance

Evaluation System: The System is Flawed and

We’re Doing Our Marines an Injustice,” Marine

Corps Gazette (Quantico, VA: January 2015);

Capt Erik Hovey, “Fuzzy Math: Do Current

Relative Values Tell an Accurate Story?” (con-

temporary issue paper, Expeditionary Warfare

School, 2005). However, we caution the reader

that none of these studies is free of errors.

8. David Freedman, Robert Pisani, and Roger

Purves, Statistics, 4th ed. (New York: W.W.

Norton & Company, 2007), 63–67.

9. See PES Manual, 8-5f and D-2. The master

brief sheet does not record the rank of a report

within the RS profile, although some Marines

misinterpret the “X of Y ” box as a rank. This

box actually records the order in which a report

was completed. “3 of 5” means the report was

the third one processed of five total reports in

the RS profile.

10. PES Manual, 8-6.

11. Of course, this means there are no Marines

in the bottom third in profile four. Since thirds

are based on the relative value, it is possible for a

third to be entirely empty in an RS profile. For

example, one of the authors wrote 13 observed

fitness reports on sergeants before a single one

fell in the middle third.

12. It takes only a slightly larger change in one

attribute mark to be the difference between a

100 and an 80.

13. By extension, it is mathematically possible

for all but one of a RS’s reports to fall either

above or below 90, regardless of how many re-

ports he or she has written.

14. This is because the relative value is a para-

metric statistic. Parametric statistics make dis-

tributional assumptions that must hold true for

the statistic to be reliable. These assumptions

generally cannot be verified without referencing

the distribution they summarize, which in this

case is the RS profile.

15. We are not the first to make this recommen-

dation, although we do so for slightly different

reasons. See, for example, Wittkoff, Rich, and

Carter, “Performance Evaluation System: Really

Taking Care of Our Marines.”

16. PES Manual, 4-22 and E-2.

17. For more information on RS profiles, see

PES Manual, 8-3ff.

18. Observed reports with an End of Service

(EN) reporting occasion are excluded from the

RS profile. They do not count toward the total of

three observed reports or receive relative values

(see PES Manual, 3-5).

19. Portions of the equation for relative value

can be found in Adam Clemens et al., An Evalu-

ation of the Fitness Report System for Marine Of-

ficers, 8n5; Manpower Management Support

Branch-30, “PES Brief for MROs and Reporting

Officials” (April 12, 2013), 25.

>Authors’ Note: We would like to thank Mi-

chael Joseph, Bryce Loidolt, Col Kurt Stein,

LtCol John Peterson, Maj Ben Connable (re-

tired), Capt Jean-Scott Dodd, Capt Royce

Hyland, Capt Megan MacDonald, Capt Pat-

rick McKavitt, Capt Nicholas Mannweiler,

CWO3 Justin Young (retired), and SgtMaj

Ernest Rose for their assistance, insight, and

criticism. All remaining errors are the fault

of the authors’ alone.

Unit Commanders

Did You Know that Subscriptions to Leatherneck

and Marine Corps Gazette are APPROVED for

Purchase with Your Unit’s Appropriated Funds?

Order your Unit Subscriptions TODAY

www .mca-marines.org

HELP YOUR PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATION

SUPPORT MARINES – JOIN TODAY!

www.mca-marines.org • 866-622-1775

Professional

Development Through

UNIT

SUBSCRIPTIONS!

Enlarged figures for:

Miscalculating Performance

How Relative Values Work, and Why the Marine

Corps Should Stop Using Them

Maj Ryan T. Baker, USMCR

Capt Yuk Wing Kwan, USMC

yuk.w[email protected]

December 4, 2015

Originally published in:

Marine Corps Gazette 99, no. 12 (December 2015): 64–68. [link]

Unfortunately, the figures in the PDF version of “Miscalculating Performance” are blurry. We’re not sure

why, but we thought it would be a good idea to make high quality versions available along with the PDF

article. Semper fidelis.

Figure 1: This figure shows how relative value is calculated using a hypothetical RS profile with six reports. The numbers on the far left are fitness

report averages; those on the far right are relative values. Each dot represents one fitness report in the RS profile. Note the absence of a bell curve, the

fact that a relative value of 80 does not mean the report is the lowest in the profile, and that no Marines fall in the middle third (we discuss thirds in

more detail later).

Figure 2: This table shows four possible RS profiles (the numbers are fitness report averages). The highlighted reports all have a report average of 3.00

and a relative value of 86.67. The RS average and RS high are also the same in each profile. The position of the report in the RS’s distribution varies

with the value of the other reports in the profile.

Figure 3: The mathematical equation for relative value.