AIRPORT

COOPERATIVE

RESEARCH

PROGRAM

ACRP

SYNTHESIS 8

A Synthesis of Airport Practice

Common Use Facilities and

Equipment at Airports

ACRP OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE*

CHAIR

JAMES WILDING

Independent Consultant

VICE CHAIR

JEFF HAMIEL

Minneapolis–St. Paul

Metropolitan Airports Commission

MEMBERS

JAMES CRITES

Dallas–Ft. Worth International Airport

RICHARD DE NEUFVILLE

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

KEVIN C. DOLLIOLE

UCG Associates

JOHN K. DUVAL

Beverly Municipal Airport

STEVE GROSSMAN

Oakland International Airport

TOM JENSEN

National Safe Skies Alliance

CATHERINE M. LANG

Federal Aviation Administration

GINA MARIE LINDSEY

Los Angeles World Airports

CAROLYN MOTZ

Hagerstown Regional Airport

RICHARD TUCKER

Huntsville International Airport

EX OFFICIO MEMBERS

SABRINA JOHNSON

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

RICHARD MARCHI

Airports Council International—

North America

LAURA McKEE

Air Transport Association of America

HENRY OGRODZINSKI

National Association of State Aviation

Officials

MELISSA SABATINE

American Association of Airport

Executives

ROBERT E. SKINNER, JR.

Transportation Research Board

SECRETARY

CHRISTOPHER W. JENKS

Transportation Research Board

*Membership as of May 2008.*Membership as of June 2008.

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2008 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE*

OFFICERS

Chair: Debra L. Miller, Secretary, Kansas DOT, Topeka

Vice Chair: Adib K. Kanafani, Cahill Professor of Civil Engineering, University of California,

Berkeley

Executive Director: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board

MEMBERS

J. BARRY BARKER, Executive Director, Transit Authority of River City, Louisville, KY

ALLEN D. BIEHLER, Secretary, Pennsylvania DOT, Harrisburg

JOHN D. BOWE, President, Americas Region, APL Limited, Oakland, CA

LARRY L. BROWN, SR., Executive Director, Mississippi DOT, Jackson

DEBORAH H. BUTLER, Executive Vice President, Planning, and CIO, Norfolk Southern

Corporation, Norfolk, VA

WILLIAM A.V. CLARK, Professor, Department of Geography, University of California, Los Angeles

DAVID S. EKERN, Commissioner, Virginia DOT, Richmond

NICHOLAS J. GARBER, Henry L. Kinnier Professor, Department of Civil Engineering,

University of Virginia, Charlottesville

JEFFREY W. HAMIEL, Executive Director, Metropolitan Airports Commission, Minneapolis, MN

EDWARD A. (NED) HELME, President, Center for Clean Air Policy, Washington, DC

WILL KEMPTON, Director, California DOT, Sacramento

SUSAN MARTINOVICH, Director, Nevada DOT, Carson City

MICHAEL D. MEYER, Professor, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Georgia

Institute of Technology, Atlanta

MICHAEL R. MORRIS, Director of Transportation, North Central Texas Council of Governments,

Arlington

NEIL J. PEDERSEN, Administrator, Maryland State Highway Administration, Baltimore

PETE K. RAHN, Director, Missouri DOT, Jefferson City

SANDRA ROSENBLOOM, Professor of Planning, University of Arizona, Tucson

TRACY L. ROSSER, Vice President, Corporate Traffic, Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., Bentonville, AR

ROSA CLAUSELL ROUNTREE, Executive Director, Georgia State Road and Tollway Authority,

Atlanta

HENRY G. (GERRY) SCHWARTZ, JR., Chairman (retired), Jacobs/Sverdrup Civil, Inc.,

St. Louis, MO

C. MICHAEL WALTON, Ernest H. Cockrell Centennial Chair in Engineering, University of

Texas, Austin

LINDA S. WATSON, CEO, LYNX–Central Florida Regional Transportation Authority, Orlando

STEVE WILLIAMS, Chairman and CEO, Maverick Transportation, Inc., Little Rock, AR

EX OFFICIO MEMBERS

THAD ALLEN (Adm., U.S. Coast Guard), Commandant, U.S. Coast Guard, Washington, DC

JOSEPH H. BOARDMAN, Federal Railroad Administrator, U.S.DOT

REBECCA M. BREWSTER, President and COO, American Transportation Research Institute,

Smyrna, GA

PAUL R. BRUBAKER, Research and Innovative Technology Administrator, U.S.DOT

GEORGE BUGLIARELLO, Chancellor, Polytechnic University of New York, Brooklyn, and Foreign

Secretary, National Academy of Engineering, Washington, DC

SEAN T. CONNAUGHTON, Maritime Administrator, U.S.DOT

LEROY GISHI, Chief, Division of Transportation, Bureau of Indian Affairs, U.S. Department

of the Interior, Washington, DC

EDWARD R. HAMBERGER, President and CEO, Association of American Railroads, Washington, DC

JOHN H. HILL, Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administrator, U.S.DOT

JOHN C. HORSLEY, Executive Director, American Association of State Highway and

Transportation Officials, Washington, DC

CARL T. JOHNSON, Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administrator, U.S.DOT

J. EDWARD JOHNSON, Director, Applied Science Directorate, National Aeronautics and

Space Administration, John C. Stennis Space Center, MS

WILLIAM W. MILLAR, President, American Public Transportation Association, Washington, DC

NICOLE R. NASON, National Highway Traffic Safety Administrator, U.S.DOT

JAMES RAY, Acting Administrator, Federal Highway Administration, U.S.DOT

JAMES S. SIMPSON, Federal Transit Administrator, U.S.DOT

ROBERT A. STURGELL,

Acting Administrator, Federal Aviation Administration, U.S.DOT

ROBERT L. VAN ANTWERP (Lt. Gen., U.S. Army), Chief of Engineers and Commanding

General, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Washington, DC

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD

WASHINGTON, D.C.

2008

www.TRB.org

AIRPORT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAM

ACRP SYNTHESIS 8

Research Sponsored by the Federal Aviation Administration

SUBJECT AREAS

Aviation

Common Use Facilities and

Equipment at Airports

A Synthesis of Airport Practice

CONSULTANT

RICK BELLIOTTI

Barich, Inc.

Chandler, Arizona

AIRPORT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAM

Airports are vital national resources. They serve a key role in

transportation of people and goods and in regional, national, and

international commerce. They are where the nation’s aviation sys-

tem connects with other modes of transportation and where federal

responsibility for managing and regulating air traffic operations

intersects with the role of state and local governments that own and

operate most airports. Research is necessary to solve common oper-

ating problems, to adapt appropriate new technologies from other

industries, and to introduce innovations into the airport industry.

The Airport Cooperative Research Program (ACRP) serves as one

of the principal means by which the airport industry can develop

innovative near-term solutions to meet demands placed on it.

The need for ACRP was identified in TRB Special Report 272:

Airport Research Needs: Cooperative Solutions in 2003, based on

a study sponsored by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

The ACRP carries out applied research on problems that are shared

by airport operating agencies and are not being adequately

addressed by existing federal research programs. It is modeled after

the successful National Cooperative Highway Research Program

and Transit Cooperative Research Program. The ACRP undertakes

research and other technical activities in a variety of airport subject

areas, including design, construction, maintenance, operations,

safety, security, policy, planning, human resources, and adminis-

tration. The ACRP provides a forum where airport operators can

cooperatively address common operational problems.

The ACRP was authorized in December 2003 as part of the

Vision 100-Century of Aviation Reauthorization Act. The primary

participants in the ACRP are (1) an independent governing board,

the ACRP Oversight Committee (AOC), appointed by the Secretary

of the U.S. Department of Transportation with representation from

airport operating agencies, other stakeholders, and relevant indus-

try organizations such as the Airports Council International-North

America (ACI-NA), the American Association of Airport Execu-

tives (AAAE), the National Association of State Aviation Officials

(NASAO), and the Air Transport Association (ATA) as vital links

to the airport community; (2) the TRB as program manager and sec-

retariat for the governing board; and (3) the FAA as program spon-

sor. In October 2005, the FAA executed a contract with the National

Academies formally initiating the program.

The ACRP benefits from the cooperation and participation of air-

port professionals, air carriers, shippers, state and local government

officials, equipment and service suppliers, other airport users, and

research organizations. Each of these participants has different

interests and responsibilities, and each is an integral part of this

cooperative research effort.

Research problem statements for the ACRP are solicited period-

ically but may be submitted to the TRB by anyone at any time. It is

the responsibility of the AOC to formulate the research program by

identifying the highest priority projects and defining funding levels

and expected products.

Once selected, each ACRP project is assigned to an expert panel,

appointed by the TRB. Panels include experienced practitioners and

research specialists; heavy emphasis is placed on including airport

professionals, the intended users of the research products. The panels

prepare project statements (requests for proposals), select contractors,

and provide technical guidance and counsel throughout the life of the

project. The process for developing research problem statements and

selecting research agencies has been used by TRB in managing coop-

erative research programs since 1962. As in other TRB activities,

ACRP project panels serve voluntarily without compensation.

Primary emphasis is placed on disseminating ACRP results to the

intended end-users of the research: airport operating agencies, service

providers, and suppliers. The ACRP produces a series of research

reports for use by airport operators, local agencies, the FAA, and other

interested parties, and industry associations may arrange for work-

shops, training aids, field visits, and other activities to ensure that

results are implemented by airport-industry practitioners.

ACRP SYNTHESIS 8

Project 11-03, Topic S10-02

ISSN 1935-9187

ISBN 978-0-309-09805-2

Library of Congress Control Number 2008925354

© 2008 Transportation Research Board

COPYRIGHT PERMISSION

Authors herein are responsible for the authenticity of their materials and for

obtaining written permissions from publishers or persons who own the

copyright to any previously published or copyrighted material used herein.

Cooperative Research Programs (CRP) grants permission to reproduce

material in this publication for classroom and not-for-profit purposes.

Permission is given with the understanding that none of the material will

be used to imply TRB or FAA endorsement of a particular product, method,

or practice. It is expected that those reproducing the material in this

document for educational and not-for-profit uses will give appropriate

acknowledgment of the source of any reprinted or reproduced material. For

other uses of the material, request permission from CRP.

NOTICE

The project that is the subject of this report was a part of the Airport

Cooperative Research Program conducted by the Transportation Research

Board with the approval of the Governing Board of the National Research

Council. Such approval reflects the Governing Board’s judgment that the

project concerned is appropriate with respect to both the purposes and

resources of the National Research Council.

The members of the technical advisory panel selected to monitor this

project and to review this report were chosen for recognized scholarly

competence and with due consideration for the balance of disciplines

appropriate to the project. The opinions and conclusions expressed or

implied are those of the research agency that performed the research, and

while they have been accepted as appropriate by the technical panel, they

are not necessarily those of the Transportation Research Board, the National

Research Council, or the Federal Aviation Administration of the U.S.

Department of Transportation.

Each report is reviewed and accepted for publication by the technical

panel according to procedures established and monitored by the

Transportation Research Board Executive Committee and the Governing

Board of the National Research Council.

The Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, the National

Research Council, and the Federal Aviation Administration (sponsor of

the Airport Cooperative Research Program) do not endorse products or

manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because

they are considered essential to the clarity and completeness of the project

reporting.

Published reports of the

AIRPORT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAM

are available from:

Transportation Research Board

Business Office

500 Fifth Street, NW

Washington, DC 20001

and can be ordered through the Internet at

http://www.national-academies.org/trb/bookstore

Printed in the United States of America

The National Academy of Sciences is a private, nonprofit, self-perpetuating society of distinguished schol-

ars engaged in scientific and engineering research, dedicated to the furtherance of science and technology

and to their use for the general welfare. On the authority of the charter granted to it by the Congress in

1863, the Academy has a mandate that requires it to advise the federal government on scientific and techni-

cal matters. Dr. Ralph J. Cicerone is president of the National Academy of Sciences.

The National Academy of Engineering was established in 1964, under the charter of the National Acad-

emy of Sciences, as a parallel organization of outstanding engineers. It is autonomous in its administration

and in the selection of its members, sharing with the National Academy of Sciences the responsibility for

advising the federal government. The National Academy of Engineering also sponsors engineering programs

aimed at meeting national needs, encourages education and research, and recognizes the superior achieve-

ments of engineers. Dr. Charles M. Vest is president of the National Academy of Engineering.

The Institute of Medicine was established in 1970 by the National Academy of Sciences to secure the

services of eminent members of appropriate professions in the examination of policy matters pertainin

g

to the health of the public. The Institute acts under the responsibility given to the National Academy of

Sciences by its congressional charter to be an adviser to the federal government and, on its own initiative,

to identify issues of medical care, research, and education. Dr. Harvey V. Fineberg is president of the

Institute of Medicine.

The National Research Council was organized by the National Academy of Sciences in 1916 to associate

the broad community of science and technology with the Academyís p urposes of furthering knowledge and

advising the federal government. Functioning in accordance with general policies determined by the Acad-

emy, the Council has become the principal operating agency of both the National Academy of Sciences

and the National Academy of Engineering in providing services to the government, the public, and the scien-

tific and engineering communities. The Council is administered jointly by both the Academies and the Insti-

tute of Medicine. Dr. Ralph J. Cicerone and Dr. Charles M. Vest are chair and vice chair, respectively,

of the National Research Council.

The Transportation Research Board is one of six major divisions of the National Research Council. The

mission of the Transportation Research Board is to provide leadership in transportation innovation and

progress through research and information exchang

e, conducted within a setting that is objective, interdisci-

plinary, and multimodal. The Board’s varied activities annually engage about 7,000 engineers, scientists, and

other transportation researchers and practitioners from the public and private sectors and academia, all of

whom contribute their expertise in the public interest. The program is supported by state transportation depart-

ments, federal agencies including the component administrations of the U.S. Department of Transportation,

and other organizations and individuals interested in the development of transportation. www.TRB.org

www.national-academies.org

ACRP COMMITTEE FOR PROJECT 11-03

CHAIR

BURR STEWART

Port of Seattle

MEMBERS

GARY C. CATHEY

California Department of Transportation

KEVIN C. DOLLIOLE

Unison Consulting, Inc.

BERTA FERNANDEZ

Landrum & Brown

JULIE KENFIELD

Jacobs

CAROLYN MOTZ

Hagerstown Regional Airport

FAA LIAISON

LORI PAGNANELLI

ACI–NORTH AMERICA LIAISON

RICHARD MARCHI

TRB LIAISON

CHRISTINE GERENCHER

COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAMS STAFF

CHRISTOPHER W. JENKS, Director, Cooperative Research Programs

CRAWFORD F. JENCKS, Deputy Director, Cooperative Research

Programs

EILEEN P. DELANEY, Director of Publications

ACRP SYNTHESIS STAFF

STEPHEN R. GODWIN, Director for Studies and Special Programs

JON M. WILLIAMS, Associate Director, IDEA and Synthesis Studies

GAIL STABA, Senior Program Officer

DON TIPPMAN, Editor

CHERYL Y. KEITH, Senior Program Assistant

TOPIC PANEL

GERRY ALLEY, San Francisco International Airport

CHRISTINE GERENCHER, Transportation Research Board

SAMUEL INGALLS, McCarran International Airport

HOWARD KOURIK, San Diego County Regional Airport Authority

ALAIN MACA, JFK International Air Terminal, LLC

TIM McGRAW, American Airlines

ROBIN R. SOBOTTA, Embry–Riddle Aeronautical University

GIL NEUMANN, Federal Aviation Administration (Liaison)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks are extended to Dr. Robin Sobotta for her major con-

tributions to the common use continuum table and chart. Additional

thanks are extended to members of the Topic Panel. Thanks are also

extended to Frank Barich, Ted Melnik, Paul Reed, Justin Phy, Yvonne

Esparza, and Theresa Belliotti for their editing and content updates.

Thanks to Alexandra, Mykenzie, Courtney, Gabriella, and Lyndsee.

Special thanks also to San Francisco Airport, Las Vegas Airport, and

JFK Terminal 4 for providing images of their airports for inclusion in

this paper.

Airport operators, service providers, and researchers often face problems for which infor-

mation already exists, either in documented form or as undocumented experience and prac-

tice. This information may be fragmented, scattered, and unevaluated. As a consequence,

full knowledge of what has been learned about a problem may not be brought to bear on its

solution. Costly research findings may go unused, valuable experience may be overlooked,

and due consideration may not be given to recommended practices for solving or alleviat-

ing the problem.

There is information on nearly every subject of concern to the airport industry. Much of

it derives from research or from the work of practitioners faced with problems in their day-

to-day work. To provide a systematic means for assembling and evaluating such useful

information and to make it available to the entire airport community, the Airport Coopera-

tive Research Program authorized the Transportation Research Board to undertake a con-

tinuing project. This project, ACRP Project 11-03, “Synthesis of Information Related to

Airport Practices,” searches out and synthesizes useful knowledge from all available

sources and prepares concise, documented reports on specific topics. Reports from this

endeavor constitute an ACRP report series, Synthesis of Airport Practice.

This synthesis series reports on current knowledge and practice, in a compact format,

without the detailed directions usually found in handbooks or design manuals. Each report

in the series provides a compendium of the best knowledge available on those measures

found to be the most successful in resolving specific problems.

FOREWORD

By Gail Staba

Senior Program Officer

Transportation

Research Board

This synthesis study is intended to inform airport operators, stakeholders, and policy

makers about common use technology that enables an airport operator to take space that has

previously been exclusive to a single airline and make it available for use by multiple air-

lines and their passengers.

Common use is a fundamental shift in the philosophy of airport space utilization. It

allows the airport operator to use existing space more efficiently, thus increasing the capac-

ity of the airport without necessarily constructing new gates, concourses, terminals, or

check-in counters. Common use, while not new to the airlines, is a little employed tactic in

domestic terminals in the United States airport industry.

This synthesis was prepared to help airport operators, airlines, and other interested par-

ties gain an understanding of the progressive path of implementing common use, noted as

the common use continuum. This synthesis serves as a good place to begin learning about

the state of common use throughout the world and the knowledge currently available and

how it is currently employed in the United States. It identifies advantages and disadvan-

tages to airports and airlines, and touches on the effects of common use on the passenger.

This synthesis attempts to present the views of both airlines and airports so that a complete

picture of the effects of common use can be gathered.

The information for the synthesis was gathered through a search of existing literature,

results from surveys sent to airport operators and airlines, and through interviews conducted

with airport operators and airlines.

Rick Belliotti, Barich, Inc., Chandler, Arizona, collected and synthesized the informa-

tion and wrote the report. The members of the topic panel are acknowledged on the pre-

ceding page. This synthesis is an immediately useful document that records the practices

that were acceptable within the limitations of the knowledge available at the time of its

preparation. As progress in research and practice continues, new knowledge will be added

to that now at hand.

PREFACE

CONTENTS

1 SUMMARY

5 CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION

Background, 5

Purpose, 5

Scope, 5

Data Collection, 6

Document Organization, 6

7 CHAPTER TWO COMMON USE CONTINUUM

Exclusive Use Model, 7

Full Common Use Model, 8

Common Use Technology, 10

State of Airports Along the Continuum, 11

13 CHAPTER THREE ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF COMMON USE

Advantages of Common Use, 13

Airport Considerations for Common Use, 13

17 CHAPTER FOUR AIRPORTS—IMPLEMENTING COMMON USE

Technology, 17

Physical Plant, 17

Competition Planning, 18

Fiscal Management, 18

Maintenance and Support, 19

21 CHAPTER FIVE AIRLINES OPERATING IN COMMON USE

Additional Resources for Planning, Design, and Implementation, 21

Airline Operations, 22

Common Use Hardware and Software, 22

Additional Costs, 22

Branding, 23

Local Support, 23

25 CHAPTER SIX REAL-WORLD EXPERIENCE

Airlines, 25

Airports, 28

30 CHAPTER SEVEN AIRPORT CONSIDERATIONS FOR COMMON USE

IMPLEMENTATIONS

Political Backing, 31

Business Model and Business Case, 31

Assessing Impact on All Airport Operations, 31

Understanding Airline Operations, 32

Airline Agreement Modifications, 32

33 CHAPTER EIGHT ANALYSIS OF DATA COLLECTION

Survey, 33

Literature, 39

Industry Sources and Experience, 39

42 CHAPTER NINE SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

45 GLOSSARY

47 REFERENCES

48 BIBLIOGRAPHY

49 APPENDIX A CUTE AND CUSS IMPLEMENTATIONS, WORLD-WIDE

64 APPENDIX B CASE STUDIES

69 APPENDIX C SURVEY INSTRUMENT

78 APPENDIX D COMPILED SURVEY RESULTS

116 APPENDIX E FAA INITIATIVE SUMMARIES

121 APPENDIX F SURVEY RESPONDENTS

Airport operators and airlines are trying to balance growth and costs. This search for balance

has caused airlines to consider carefully how changes at airports affect the airlines’ overall

expenses. It has also encouraged airport operators to find alternative ways to facilitate growth

and competition, while keeping the overall charges to the airlines as low as possible. The

entry of many new low-cost carriers has also highlighted the need to keep costs down at

airports. One opportunity that airport operators around the world are seizing is the imple-

mentation of common use. Common use technology enables an airport operator to take space

that was previously assigned exclusively to a single airline and make it available for use by

multiple airlines and their passengers.

Common use is a fundamental shift in the philosophy of airport space utilization. It allows

the airport operator to use existing space more efficiently, thus increasing airport capacity

without necessarily constructing new gates, concourses, terminals, or check-in counters.

In the construction of new gates, concourses, terminals, or check-in counters, it has been

determined by de Neufville and Belin that the deployment of a common use strategy can help

an airport save up to 30% of the costs of such new construction. Common use, although not

new to the airline industry, is a seldom-employed tactic in domestic airline terminals in the

United States.

This synthesis was prepared to help airport operators, airlines, and other interested parties

gain an understanding of the progressive path of implementing common use, noted as the

“common use continuum.” It serves as an introduction to the state of common use through-

out the world, reviews the knowledge currently available, and provides examples of how it is

currently employed in the United States. The report identifies advantages and disadvantages

of common use to airports and airlines, and touches on how common use affects the airline

passenger. It also presents seven case studies of real-world experiences with common use.

This synthesis presents the views of both airlines and airports so that a complete picture of

the effects of common use can be determined.

Information for this synthesis was gathered through a search of existing literature, surveys

sent to airport operators and airlines, and through interviews conducted with airport opera-

tors and airlines. Because the common use continuum is an ever-changing concept and

practice, the literature search generally was restricted to information less than seven years

old. Resources used in conducting the literature search included industry organizations [Inter-

national Air Transport Association (IATA), ATA, ACI-NA], Internet and web searches, and

vendor documents.

In conjunction with the literature search, surveys were sent to a broad sample of airports,

including European, Asian, and North American airports. The airports selected had varying

experiences with common use so as to gain an accurate picture of the state of common use

throughout the industry. Surveys were also sent to airlines from the same regions and with

the same varying experiences with common use. A total of 13 airlines and 24 airports were

invited to complete the surveys; with survey responses received from 12 airlines and 20 air-

ports, an overall response rate of 86%.

SUMMARY

COMMON USE FACILITIES AND EQUIPMENT

AT AIRPORTS

The survey responses confirmed that airports outside of the United States have progressed

further along the common use continuum. This affects U.S. airlines that fly to destinations

outside the United States, because they have to operate in airports that are already moving

along the common use continuum.

Interviews were conducted with representatives from airlines and airports that have

implemented common use in some fashion. The airlines interviewed included Alaska Air-

lines, American Airlines, British Airways, and Lufthansa Airlines. The airports interviewed

included Amsterdam Airport Schiphol, Las Vegas McCarran, and Frankfurt International

Airport. Interviews were also conducted at Salt Lake City Airport because it had previously

considered, but chose not to implement, common use.

The information acquired was processed and is presented in this synthesis. From the

information, the following conclusions were drawn:

• Industry-Wide Importance and Benefit of the Common Use Continuum

Common use is of a growing interest to airports and airlines. Although the literature and

available recorded knowledge are limited, common use is an important field and has a

great impact on the airport and airline community. U.S. airport operators and airlines

have an opportunity to benefit from the implementation of common use technology. Air-

port operators gain by using their space more efficiently, expanding the capacity of the

airport, providing for greater competition, being more flexible in the use of the space, and

creating an environment that is easier to maintain. Airlines gain greater flexibility in

changing schedules (either increasing or decreasing service) and greater ease in accom-

modating failed gate equipment or other disruptive operational activities, such as con-

struction; acquire the opportunity to lower costs; and potentially obtain a lower cost of

entry into a new market. The converse is also true, in that if a common use implementa-

tion is poorly planned and implemented, airport operators and airlines stand to lose.

Passengers also recognize the benefits of common use. When an airport operator

moves along the common use continuum, the passenger experience can be greatly en-

hanced. Common use enables airport operators and airlines to move the check-in

process farther from the airport, thus allowing passengers to perform at least part of the

check-in process remotely, sometimes at off-site terminals. In some cases, the passen-

ger can complete the check-in process, including baggage check, before ever entering

the airport. This allows passengers to travel more easily, without the need to carry their

baggage.

It also allows the passenger to have a more leisurely trip to the airport and to enjoy

their travels a little longer, without the stress of having to manage their luggage. Pas-

sengers arriving at an airport that has implemented common use have more time avail-

able to get to their gate and may not feel as rushed and frustrated by the traveling expe-

rience.

Passengers also benefit because space utilization can be optimized as necessary to

accommodate their needs. In today’s environment, air carriers often increase their

schedules very dynamically. With dynamic changes, passengers can suffer by being

placed into waiting areas that are too small and/or occupied, and by having to cope with

concessions, restroom facilities, and stores that are unable to accommodate the

increased demand. Through common use, the airport operator is able to adjust airport

space dynamically to help accommodate passenger needs. This creates a positive expe-

rience for the passenger, and results in a positive image of both the airport and the

airline. This positive experience can lead to recognition and increased business for the

airlines and the airport operators.

2

• Lack of Information Resources

Throughout this process, it has become evident that the lack of resources available to

educate interested parties leads to their gaining knowledge about the benefits of com-

mon use through site-specific experience—an inefficient way of learning about this

industry “best practice.” There is a significant amount of “tribal” knowledge through-

out a portion of the industry; however, it has not been formally gathered and evaluated

for industry-wide consumption. Most of the existing documented sources consist of

vendor-provided marketing materials. Although the key concepts of common use may

be gleaned from these documents, they do not present a balanced, unbiased picture

of the common use continuum to assist stakeholders in learning about common use.

Unlike some topics, there was no central place to go to learn about the topic of common

use. Information available from industry organizations, such as IATA, is provided at a

very high level or is not freely available.

• Need for Careful Planning and Open Communication

It is important that any movement along the common use continuum be carefully con-

sidered so that the benefits and concerns of all parties are addressed. Airport operators

must consider whether or not common use would be appropriate at their airport. If the

airport has only one or two dominant carriers, it may not make sense to move too far

along the common use continuum. If common use were to become widely adopted

throughout the United States, however, more of the “dominant” carriers at many loca-

tions would be inclined to work in a common use environment. In essence, this is a

“Catch-22” situation, where the wide acceptance of common use technology is some-

what dependent on it being widely accepted. Airports and airlines must work closely

together during the design of the common use strategy at each airport operator’s loca-

tion to ensure that the passengers receive the benefit of the effort.

It is the airline that brings the customer to the airport, but it is the airport that is nec-

essary for the airline to operate in a given market. Both airlines and airport operators

must move toward working together cooperatively for the benefit of their mutual cus-

tomer.

It is important for both airlines and airport operators to communicate openly and

honestly when introducing common use. If airport operators include airlines, ground

handlers, and other stakeholders in the design process, then all interested parties are able

to affect the outcome of the strategy, usually for the better. In addition, the airport

operators should make an extra effort to ensure that airline participation is facilitated.

Having tools that facilitate remote meetings along with face-to-face meetings is one way

to allow the inclusion of airline staff. Airlines, likewise, need to make a commitment

to participate in the process. When an airport operator moves along the common use

continuum, it is in the best interest of the airline to participate in the design. In many

cases, the airport operator will move forward without the input of the airlines, if the air-

lines refuse to participate.

• Understanding of the Airlines’ Resistance to the Common Use Continuum

In general, U.S. airlines have a skeptical view of common use for many reasons. As will

be shown in the body of this synthesis, when a non-U.S. airport operator views common

use as a profit center, the airlines are not inclined to favor the initiative.

Also, when airport operators move along the common use continuum without the

input of the airlines currently serving that airport there is distrust in their motivation and

also a concern that the strategy will not support the airlines’ business processes put in

3

place to support their passengers. The converse is also true, in that the airlines must sup-

port the airport operators in their common use implementation strategy to ensure the air-

ports achieve maximum benefit from the common use implementation.

The common use continuum continues to be of interest to airports and airlines as both

ACI–NA and IATA are at the forefront, creating the standards and recommended practices

governing the common use continuum.

Through further development, experience, and knowledge of the common use continuum,

the airport and airline industry can jointly discover new ways to accommodate growth and

competition.

4

5

BACKGROUND

The U.S. air travel industry is undergoing a period of econo-

mization to remain competitive and solvent. As a result, air-

lines and airport operators are working together to reduce

costs and make air travel more efficient. At the same time,

the air travel industry continues to look for ways to improve

customer service, the customer experience, and to speed up

the passenger processing flow.

Concurrent with the airlines seeking to economize to re-

duce their operating costs is that airport operators across the

United States are regaining control of their airport re-

sources (i.e., terminals, gates, etc.) through the expiration

of long-term leases, and sometimes by airlines ceasing or

dramatically reducing operations at the airport operators’

locations. This has caused U.S. airport operators to reeval-

uate the business model used to work with airlines to ensure

the local needs of the cities being served are met, as well as

the needs of the airlines.

One solution with the potential for addressing these

needed areas of improvement is the implementation of com-

mon use. Common use enables an airport operator to take

space that has previously been exclusive to a single airline

and make it available for use by multiple airlines. These

spaces include ticketing areas, gate hold rooms, gates, curb-

side areas, loading bridges, apron areas, and club spaces.

Common use provides airports and airlines with the ability to

better manage operations in the passenger processing envi-

ronment, improving passenger flow and ultimately reducing

overall costs. However, even with more than two decades of

implementation history, the benefits of common use are still

not adequately catalogued.

Common use may also include any space that is used or

can be used to provide a service to the passenger. In this way,

parking lots, baggage claim areas, and passageways can be

considered common use. Common use also affects physical

plant facilities such as preconditioned air and power. Other

systems typically affected include ticketing, kiosks, baggage

systems, check-in, next-generation check-in, and telephony.

Airport common use systems also are increasingly being em-

ployed in cruise ship terminals, hotels, ground transportation,

and other nonairport environments.

PURPOSE

The objective of this synthesis is to provide a document that

consolidates information on common use for airports in a sin-

gle source. This report therefore functions as a good starting

point in the understanding of common use. It is intended that

this synthesis be presented to all stakeholders, including air-

lines, airport operators, passengers, government entities,

vendors, and ground handlers.

The synthesis assembles literature and survey informa-

tion on the effect of common use on airport and airline fi-

nances, technology, operations, facilities, and business and

policy decisions. Common use information is synthesized

from the perspectives of passenger processing, ground

handling, and technology infrastructure. The synthesis

should leave the reader with a better understanding of com-

mon use and the expected risks, rewards, and issues that

may exist.

SCOPE

This synthesis presents the research conducted with airports,

relevant committees, airlines, and applicable vendors on

their collective experience with current and planned common

use strategies. Throughout the document, the synthesis draws

from both actual experiences to date, as well as from known

future developments.

Collection of information was through the following

resources:

• Existing knowledge source research:

– Objective literature from international and domestic

locations on facilities and practices (whether or not

common use is in place);

– Aviation industry emerging standards;

– Airline literature;

– International Air Transport Association’s (IATA’s)

Simplifying the Business surveys, initiatives, and

articles; and

– Applicable vendor literature.

• Airline and airport surveys (conducted in coordination

with this synthesis).

• Interviews with airport operators and airlines represent-

ing different aspects of common use implementation.

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

DATA COLLECTION

Data for this synthesis were collected in the following ways.

First, a thorough literature search was conducted to deter-

mine the scope of available information. This search revealed

that whereas journal articles and documentation exists, it is

not abundant—highlighting the relative lack of information

on this topic industry-wide. Of the documentation found

through the literature search, it was noted that many of the

same people were interviewed for inclusion in the articles.

An Internet search was also conducted, which revealed a

limited amount of available information on common use. Most

of the information available was provided by vendors in the

form of marketing material. Although information can be

gleaned from these documents, they do not present a balanced,

unbiased picture of common use strategies to assist stakehold-

ers in the learning process. Unlike some topics, there was no

central place to go to study the topic of common use. Informa-

tion available from industry organizations, such as IATA, is

provided at a very high level or is not freely available.

Information was also obtained from IATA, vendors who

provide common use solutions, and airlines and airports that

have implemented these solutions. This information was

primarily focused on CUTE (Common Use Terminal Equip-

ment) and CUSS (Common Use Self-Service) installations

(discussed further later in this synthesis). A spreadsheet

containing the information acquired is contained in Appen-

dix A. The researchers verified the data contained in this

spreadsheet to confirm their accuracy; however, as time pro-

gresses, the data will become stale, and ultimately irrelevant.

Additional information was gathered through interviews,

conversations, and experience. Although this synthesis does

not formalize the collection of this interview information,

primary use of the knowledge gathered is found in chapters

two through five.

Surveys were also conducted to find out the state of

the industry, both in implementation and understanding

6

of common use strategies. Full survey results can be found

in Appendix D. The survey results are analyzed later in

this document. Separate surveys were sent to airlines and

to airports. This was done primarily because the perspec-

tive of each is different, and therefore warranted different

questions.

DOCUMENT ORGANIZATION

Chapter one contains the background information required to

set the basis for the remaining chapters. Chapter two uses the

information gathered through the existing knowledge

sources noted in chapter one and presents the general pro-

gression for implementing common use. This is noted as the

“common use continuum.” This chapter discusses the vari-

ous systems and technologies typically associated with com-

mon use. To support its case, the synthesis references specific

industry documentation or “expert knowledge” sources

where applicable. Chapter three presents information on the

perceived advantages and disadvantages of common use

from airline, airport, and passenger perspectives. As with

chapter two, this chapter presents its findings from informa-

tion gathered through the existing knowledge sources noted

in chapter one. Chapters four and five build on the informa-

tion presented in chapters two and three and reviews business

and operational practices affected by common use. These

chapters further discuss modifications needed to implement

common use from both the airline and the airport perspec-

tives. Chapter six presents seven case studies representing

different aspects of “real-world” common use implementa-

tions. Further information on the case studies and the inter-

view process is included in the appendices. Chapter seven

presents airport considerations for common use implementa-

tions. Chapter eight provides the results and analysis of a

survey conducted as part of the synthesis. Chapter nine sum-

marizes the findings and presents suggestions for further

study.

Appendices are included where needed for supporting

documentation and are noted throughout this synthesis.

7

Airport operators and airlines are continually looking for op-

portunities to be more efficient and at the same time improve

the customer experience. In this search for efficiency, every as-

pect of the business model is reviewed, analyzed, and inspected

to determine if there are better ways to provide a more stream-

lined travel experience at a lower cost and a higher profit. It is

at the airport where the goals of airports and airlines meet. Air-

lines may be looking to increase or decrease the number of

flights to a given market, change seasonal flight schedules to

meet demand, or adjust their fleet based on the requirements of

a given market. Airport operators, on the other hand, are look-

ing for ways to improve and ensure the continuity of the service

provided to their region by adding flights, adding additional air-

lines, and maximizing the use of their facilities.

One key factor in any decision making is the cost of

doing business in a given market. “Airport operators are

constantly challenged by the dual objective of needing to

maximize limited resources while providing a passenger-

friendly experience” (Finn 2005). Because of these contra-

dictory factors, airport operators are challenged with

increasing their passenger throughput while minimizing

their capital expenditures and construction. One effective

way to reduce capital expenditures is to develop programs to

utilize existing space more efficiently so that capital expen-

ditures end up being deferred. It has also been shown that

once capital expenditures are incurred for new construction

of a gate, concourse, or terminal, these costs can be reduced

by as much as 30% if a common use strategy is used in the

design (de Neufville and Belin 2002).

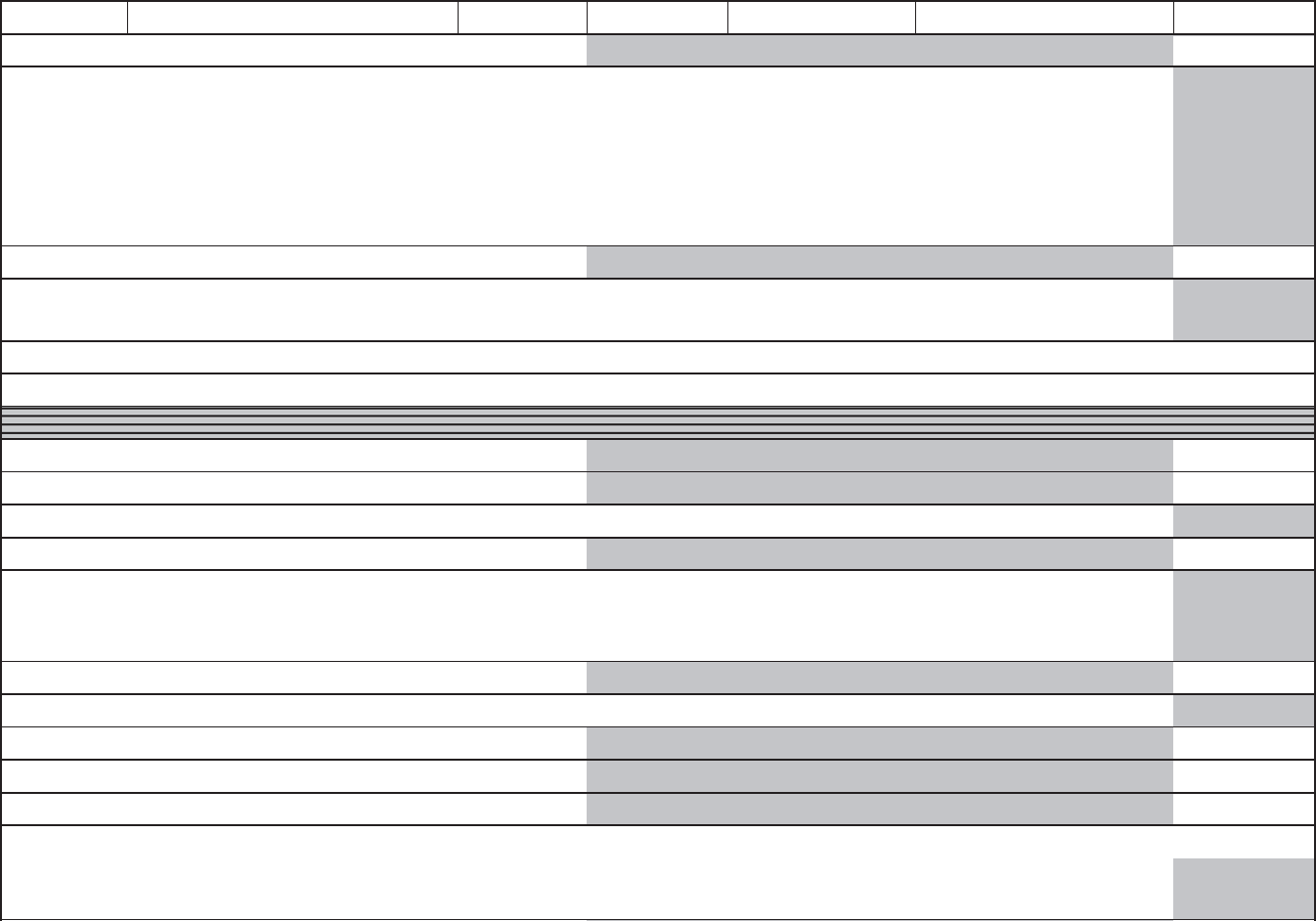

The concept of the common use continuum, as shown in

Figure 1, indicates that airport operators can gain centralized

control over facilities and technology, increase passenger pro-

cessing options, and acquire shared use efficiencies as they

move from exclusive use toward common use. Conversely,

airline tenants in an exclusive use arrangement retain a level

of tenant autonomy over their physical space. Airport com-

mon usable space is defined as space in which any airline may

operate and, as space that is not specifically dedicated to any

single airline. As shown in Figure 1, it is highly unlikely that

any airport with more than one airline servicing it does not

provide some level of common use. Table 1 defines several

airport management models on the common use continuum,

shows key differences and benefits of each, differences in

common use locations, and their impact on key stakeholders

(e.g., airlines, passengers, and airport operators).

All airports begin with a basic level of common use.

Based on interviews, once an airport facility moves beyond

the basic level, the airport operator, airlines, and passengers

begin to see additional benefits with common use. Beyond

the basic level, however, there is an inherent lag-time be-

tween when an airport is capable of a common use model and

when they choose to implement that common use model. As

explained in chapter seven, there may be operational and

business considerations that have to be identified before

moving along the common use continuum.

EXCLUSIVE USE MODEL

At one end of the common use continuum is the exclusive use

model. This model defines all airline-specific space as used

exclusively by a given airline. In this model, each airline has

dedicated ticketing counters, gates, office space, ramp space,

etc. Airlines have traditionally favored this model because it

gives them the most direct control over their flight schedule

and operations. The airline provides gate management and

other specialty applications to ensure efficient operations

within the airline’s allotted space. To add flights, the airline

must have space available at its gates or be able to acquire

additional gates at the airport.

In the exclusive use model, airlines pay for the space, even

if the airline is not using that space. Airport operators therefore

reap the benefit of having space leased whether it is actively

used or not. Another benefit for the airport operator is that man-

agement of space is minimal. In the exclusive use model, air-

port operators only manage their airport usage based on airline

and total number of gates used exclusively by those airlines.

Airports, however, do not achieve maximum utilization in

the overall use of the facility, especially if the airlines that

service that airport do not have fully loaded schedules.

There will be obvious times of day when concourses will

be crowded, with many flights arriving and departing at the

same time, as well as times when the concourses are com-

pletely empty. The airport operator has few options available

to manage the peaks and valleys in the demand effectively

over the course of a day.

As more flight services are added within peak time peri-

ods in the airport, the airport operator must add more gates

and/or counter space. Once the airport operator is physically

CHAPTER TWO

COMMON USE CONTINUUM

8

unable to add more gates, the growth of service to that airport

stops. Likewise, as airlines add more flights into their sched-

ule to a specific market, they must manage these flights based

on the physical limitations of the exclusive space leased. At

some point, the only way to add new flights or new airlines

under the exclusive use model is to remove other services or

wait until another airline relinquishes space.

In the exclusive use model, passengers are affected by the

peaks and valleys caused by the flight schedules of the various

airlines. In all areas of the airport, a peak demand of flights is

the root cause of congestion. “Passengers are eager to reduce

the time spent ‘processing’” (Behan 2006). To the passenger,

the airport is not the destination, but merely a point along a

journey. The goal should be to move passengers through that

point as expeditiously as possible. The exclusive use model

may be a reasonable choice for airports that do not have a large

number of airlines servicing the airport. If the airport has one

or two dominant carriers, or if a particular terminal within an

airport is dominated by a few carriers, the airport operator may

choose not to implement common use. If the airport is not re-

quired to complete a competition plan, or is not planning to add

additional airlines, then a traditional exclusive use model will

probably remain and limited common use strategies and tech-

nologies may be implemented instead. For instance, for a hub

airport, where 60% or more of the airport usage is dominated

by one airline (e.g., Salt Lake City International Airport), a

common use strategy may not make sense. The remaining

40% (or less) of airport capacity, however, may represent an

excellent opportunity for common use implementation, be-

cause the remaining 40% of the gates may be in high demand.

As will be discussed later, these “hub” airport operators need

to consider all potential scenarios that could result if one of

their dominant airlines ceased operations, or declared bank-

ruptcy, necessitating drastic changes in its operations.

FULL COMMON USE MODEL

At the other end of the common use continuum is the full com-

mon use model. In this model, all airline usable airport space

is available for use by any airline. The goal of the full common

use model is to minimize the amount of time any given airline

resource is not in use, as well as maximize the full use of the

airport. Airports benefit from increased utilization of existing

resources. In a full common use airport, airlines are assigned

with no preferences given to any individual airline, similar to

the air traffic control process. For example, each aircraft is put

in the queue and assigned to a gate that best fits the needs of the

airport gate management process. Technology plays a key role

in the full common use model. To manage resources properly,

computer software and systems are put in place to perform

complex calculations, monitor usage, and provide status re-

porting. There are no dedicated spaces in a full common use

airport. All resources are managed very closely by the airport

operator, and the result is an efficient use of limited resources.

Airlines are less comfortable with this model because it

removes direct control over their gate assignments within the

market. The benefit of this model to the airlines, however, is

more flexibility. Gates and ticket counters that were once ex-

clusively held by a competing airline 24 hours a day, 7 days

a week now become available for everyone’s use.

Airlines can enter markets, expand in markets, and even

exit markets much easier under this model because the lease

changes from exclusive to common use. Although there are

many models for leasing, airlines begin paying for only the

portion of the airport used. In addition, there are more

options available to airlines should a flight be delayed. The

airline no longer has to wait for one of its exclusive gates to

become available; the flight can be assigned to any available

open gate. A common use airport allows “...carriers to focus

on what they do best: moving passengers from one destina-

tion to another” (Guitjens 2006).

Airport operators must manage airport space at a more de-

tailed level under the full common use model. The airport

operator takes on full responsibility for the common use infra-

structure; any service that is space-specific must now be

viewed as common use. For example, jet bridges are now pur-

chased and maintained by the airport operator. Again, tech-

nology plays a large role in allowing this to take place. As with

space-specific resources, the common use terminal equipment

(CUTE) systems and hardware also become the airport opera-

tor’s responsibility, except in the cases of CUTE Local User

Boards (CLUB) models. Airports benefit from increased uti-

lization of existing resources. A CUTE CLUB is a system in

which the airlines make the decisions on how the CUTE sys-

tem will be paid for, operated, and maintained, for the benefit

of all the CUTE CLUB members. Under this scenario, the air-

port operator does not usually own the CUTE system. In the

United States this model is sometimes modified, where main-

tenance of the common use system is under a “CUTE CLUB”

type model, while the airport retains ownership of the assets.

The passengers’ experience in the full common use model

is improved as they flow through the process of enplaning or

Airport Passenger Processing “Common Use” Continuum

Common

Use

Preferential

Use

Exclusive

Use

Mixed Use

FIGURE 1 Common use continuum.

Models Exclusive Use (EU) Mixed Use (MU) Preferential Use (PU) (Full) Co mm on Use (CU)

Approach

Passenger Processing

Facilities (PPFs), technology,

and agreem ents are

predom inately owned/leased

and operated by singular

users.

Som e investment and conversion

to CU PPF technology and

system s. CU equipm ent may be

installed but not implemented,

pending renegotiation.

Substantial invest me nt and conversion to

CU technology and systems. PU

agreem ents are established, allowing select

tenants priority over space under specific

term s.

Complete commitment to CU equipment,

system s, and agreem ents. (Few or no EU

or PU agreem ents.) CU ma y extend

beyond term inal curbs and walls (to ramps

and other facilities).

Common

Use

Locations

Som e baggage claim devices,

paging system s, access

control, building system s, etc.

CUTE in new/remodeled areas,

international gates/jet bridges,

CCTV, CUSS, re mo te check -

in/out, inform ation displays, etc.

CUTE at all PPFs, including ticket

counters and in gate ma nagem ent.

Extensive com puter/phone system

hard/software acquisition and integration.

CU ma y extend to ram p area: gate

ma nagem ent, ground handling (GH), and

other airport and non-airport areas.

Stakeholders EU tends to: MU tends to: PU tends to: CU tends to:

Airports

Create underutilized spaces

Deter new air service

entrants

Help to ensure air service

continuation by som e

existing airlines in

precarious ma rkets

Increase efficient use of

selected underutilized spaces

Reduce space expansion needs

Prom pt renegotiation of

existing agreem ents

Familiarize tenants with CU

Increase efficient use of underutilized

spaces

Reduce future expansion needs/costs

Increase technology costs/expenditures

Offer mo re consistency for users than

MU

Require staff/vendor for CU

main tenance and IT functions. (Assume

risks with outages.)

Maxi mi ze efficient use of space and

technology

Require high initial technology

invest me n t , b u t resu lt in long er term per

passenger savings

Reduce future expansion needs/costs

Allow increased access to new entrants

Require staff/vendor for GH functions

Passengers

Be relatively uncomplicated

and allow ease in way-

finding

Lim it PP F choices

Increase PPF choices

Complicate way-finding, if not

consistently used

Increase PPF choices

Offer elevated tenant consistency, which

supports way-finding

Increase PPF choices

Support way-finding if coupled with

effective dynam ic signage

Tenant/Airline

Offer high tenant autonom y

and perception of ìcontrol ”

Support traditional branding

of physical spaces

Allow use of existing

co mp any

equipm ent/program s, so no

retraining/learning curve

Lim

CUTE = common use terminal equipment; CCTV = closed-circuit television; CUSS = common use self-service; IT = information technolo

gy

.

it access to com petitors

Lessen tenant autonom y

Lessen opportunity for

traditional branding of spaces

Require CU technology

training (learning curve)

Allow som e increased access

and cost benefits

Create delays in transactions

atte mp ted on CU equipment

Lessen tenant autonom y

Prom pt branding concerns, unless

addressed with dynam ic signage

Require CU technical training (learning

curve)

Create dependence on non-airline

personnel (for CU system main tenance)

Provide space for em ergencies and new

service

Allow for cost savings when

underutilized spaces are released

Lessen tenant autonom y

Prom pt branding concerns, unless

addressed with dynam ic signage

Require CU technical training (learning

curve

Additionally create dependence on non-

airline personnel for ground handling

Provide space for em ergencies and new

service

Allow for cost savings when

underutilized spaces are released

TABLE 1

COMMON USE CONTINUUM

10

deplaning. This improvement is the result of more efficient

flow through the airport. Because the overall airport space is

used more efficiently, congestion, queues, and general

crowding can be better managed and peaks in flight sched-

ules can be spread across the airport more efficiently. Com-

mon use implementation can lead to satisfied customers and

result in awards to airports and airlines for improved cus-

tomer service, such as the Las Vegas McCarran International

Airport’s 2006 J.D. Power & Associates award for customer

service (Ingalls 2007).

As will be discussed later in this document, there are chal-

lenges, concerns, and risks involved with implementing

common use. Airport operators surveyed and interviewed for

this report indicated that often, airlines are not always will-

ing to make the change from proprietary, exclusive space, to

some other step along the common use continuum. As shown

in Table 1, as airport operators move their airports along the

common use continuum, airlines perceive a loss of autonomy

and control over their operations.

COMMON USE TECHNOLOGY

The role of technology is critical in implementing common

use because the processes needed to manage a common use

environment are complex. Technology systems can include:

• Networking—both wired and wireless,

• Passenger paging systems—both audible and visual,

• Telephone systems,

• Multi-User Flight Information Display Systems

(MUFIDS) (see Figure 2),

• Multi-User Baggage Information Display Systems

(MUBIDS),

• Resource and gate management,

• Common use terminal equipment (CUTE),

• Common use self-service kiosks (CUSS),

• Local departure control systems (LDCS),

• Airport operational database (AODB),

• Common use baggage sorting systems, and

• Baggage reconciliation.

Although this list is not exhaustive, it does demonstrate the

impact that technology has on making an airport common

use.

Common use technology implementation requires coordi-

nation among several entities, which ultimately become part-

ners in this endeavor. These partners include the platform

provider, the entity that provides the technology and the

hardware; the application provider, the entity that provides

the computer applications that operate on the technology and

the hardware; and the service provider, the entity that pro-

vides first- and second-level support for the technology.

These partners, together with the airport operator and the air-

lines, must cooperate to make any common use technology

implementation successful (Gesell and Sobotta 2007).

Wired and wireless networks, often referred to as premises

distribution systems (PDS), are the backbones of all other

technology systems. The PDS provides a way for technology

systems to be interconnected throughout the airport campus

and, if necessary, to the outside world.

Although a PDS is not necessary in a common use envi-

ronment, it is does allow for the management of another finite

resource—the space behind the walls, under the floors, in the

ceilings, and in roadways.

Passenger paging systems are those systems used to com-

municate information to the passenger. Traditionally, this

system was the “white paging phone” and the audio system

required to broadcast messages throughout the airport. These

systems are installed inside buildings in almost all passenger

areas, and used by the airport staff, airlines, and public

authorities. Today, these systems are expanding to include a

visual paging component for those who are deaf or hard of

hearing.

MUFIDS are dynamic displays of airport-wide flight in-

formation. These consolidated flight information displays

enable passengers to quickly locate flight information and

continue on their journey (see Figure 2). MUBIDS are dy-

namic displays capable of displaying arriving baggage

carousel information for more than one airline. MUFIDS,

MUBIDS, and a resource management system should inter-

act with a central AODB to aid and complement the most

efficient utilization of an airport common use system. Imple-

mentation of multi-user displays manages the space required

to communicate flight information.

Resource and gate management systems allow the airport

operator to effectively manage the assignment of gates and

associated passenger processing resources to airlines. These

FIGURE 2 Multi-user flight information display systems

(MUFIDS).

11

systems operate on complex algorithms to take into account

information such as preferential gate assignments, altered

flight schedules, size of aircraft, and other factors that affect

the airline use of gates. Such systems may tie into accounting

and invoicing systems to assist the airport operator with air-

line financial requirements.

CUTE systems allow an airport to make gates and ticket

counters common use. These systems are known as “agent-

facing” systems, because they are used by the airline agents

to manage the passenger check-in and boarding process.

Whenever an airline agent logs onto the CUTE system, the

terminal is reconfigured and connected to the airline’s host

system. From an agent’s point of view, the agent is now

working within his or her airline’s information technology

(IT) network. CUTE was first implemented in 1984 for the

Los Angeles Summer Olympic Games (Finn 2005). It was at

this point that IATA first created the recommended practice

(RP) 1797 defining CUTE. It should be noted that ATA does

not have a similar standard for common use. From 1984 until

the present, approximately 400 airports worldwide have in-

stalled some level of CUTE.

Since 1984, several system providers have developed

systems that, owing to the vagueness of the original CUTE

RP, operate differently and impose differing airline system

modifications and requirements. This has been problematic

for the airlines, which must make their software and opera-

tional model conform with each individual, unique system.

Making these modifications for compatibility’s sake has

been a burden for the airlines.

As a result, IATA is currently developing a new standard

of RPs for common use systems called “common use pas-

senger processing systems” (CUPPS). The updated RP was

expected to gain approval at the fall 2007 Joint Passenger

Services Conference (JPSC), conducted jointly by ATA and

IATA. Subsequent IATA plans are that the CUPPS RP will

fully replace the current CUTE RP in 2008. This action will

eliminate airline concerns about continuing system compati-

bility to manage multiple system/vendor compatibility.

In addition to IATA, the CUPPS RP is to be adopted by

ATA (RP 30.201) and ACI (RP 500A07), giving the RP

industry-wide endorsement. The Common Use Self-Service

(CUSS) Management Group is monitoring the progress of

the CUPPS committee to assess future migration with

CUPPS.

“CUSS is the standard for multiple airlines to provide a

check-in application for use by passengers on a single [kiosk]

device” (Simplifying the Business Common Use Self Service

2006). CUSS devices run multiple airlines’ check-in appli-

cations, relocating the check-in process away from tradi-

tional check-in counters. Passengers can check in and print

boarding passes for flights in places that heretofore were

unavailable. Examples include parking garages, rental car

centers, and even off-site locations such as hotels and con-

vention centers. The CUSS RP was first published by IATA

in 2003 (Behan 2006) (see Figure 3 for a display of CUSS

kiosks).

LDCSs are stand-alone check-in and boarding systems.

These systems allow airlines that do not own or have access

to a host-based departure control system (e.g., seasonal char-

ter operators) to perform electronic check-in and boarding

procedures at the gate. Without an LDCS, airlines that do not

have access to a departure control system must board pas-

sengers through a manual process.

AODBs are the data storage backbone of a common use

strategy. These databases enable all of the technology com-

ponents of a common use environment to share data. The

AODB facilitates integration between otherwise disparate

systems and enables data analysis and reporting to be com-

pleted on various components of the common use system.

These databases also help in the calculation of charges for

airport operators. Baggage recognition systems provide the

necessary components to track bags and ensure that they

reach their intended aircraft.

Baggage reconciliation systems provide positive bag

matching, baggage tracking, and reporting functionality. As

airports move along the common use continuum, common

baggage systems, and eventually common baggage drop lo-

cations, will necessitate the need for baggage reconciliation

systems.

STATE OF AIRPORTS ALONG THE CONTINUUM

Common use acceptance and implementation differ dramat-

ically between U.S-based airports and non-U.S-based

airports. Much of this relates to the geography of the coun-

tries, as well as to the history of how airports were founded

in the United States versus other countries. In Europe, for ex-

ample, the close proximity of multiple countries makes the

FIGURE 3 Common use self-service kiosks.

12

majority of flights international. Because these airports sup-

port more international flights, they have been more disposed

to implementing common use. Historically, airports in the

United States were developed in conjunction with a flagship

carrier. These relationships resulted in long leases and cre-

ated the hub airport. European airports were developed

mostly by governments and therefore do not have as many

long-term leases with flagship carriers.

Although most airports started out as exclusive use, many

have begun the journey along the common use continuum.

Some U.S.-based airport operators, such as at Westchester

County Airport (White Plains, N.Y.), manage counter and

gate space by use of a lottery system (McCormick 2006),

whereas other airport operators, such as at Orlando Interna-

tional Airport, assign gates and counter space by preferential

use and historical precedence (“Common Use Facilities”

2004). Some airports employ a minimalist “use it or lose it”

approach to gate assignments.

Another U.S.-based airport that has migrated along the com-

mon use continuum is Terminal 4 at JFK. JFK, Terminal 4, is

unique in the United States in that it is operated by JFK IAT,

LLC, a private consortium of Amsterdam Airport Schiphol;

LCOR, Inc.; and Lehman Brothers. Unlike an airline-operated

terminal, Terminal 4 serves multiple international and domes-

tic airlines and manages its gate allocations (Guitjens 2006).

The Clark County Airport Authority at Las Vegas

McCarran International Airport has taken a slightly different

common use approach by moving check-in operations off

site. The airport operator has installed CUSS kiosks in

locations such as hotels, convention centers, and other desti-

nations where travelers may be located. By doing this, the

airport operator has effectively extended the stay of vaca-

tioning passengers, allowing passengers to perform most of

their check-in processes (e.g., check bags and obtain board-

ing passes) before coming to the airport.

Outside the United States, airport operators are also mov-

ing along the common use continuum. Amsterdam Airport

Schiphol has long been identified as a leader in the effort to

improve passenger processing. Much of the airport is com-

mon use, even though the airport has a dominant carrier,

KLM. Amsterdam Airport Schiphol is working on fully

automating the passenger process from check-in, through

border crossing, and finally through security.

To understand common use, it is helpful to understand,

from a technology point of view, how many airports in the

world (outside the United States) have enthusiastically

adopted CUSS and CUTE. The reason that these two systems

are a focus is because they serve as key ingredients in the

common use continuum. Based on information from vendors,

IATA, airports, and airlines, as of June 2007, approximately

400 airports worldwide had some level of CUTE installed.

Approximately 80 airports worldwide have CUSS installed.

As mentioned earlier in this document, CUTE has been in

existence since 1984, whereas CUSS has been in existence

since 2003. It is interesting to note that only 60 airports

worldwide have implemented both CUSS and CUTE (see

Appendix A for more detail).

Common use implementations are increasing annually.

For example, in 2005, seven airports had signed memoranda

of understanding with IATA to implement CUSS. By early

2006, 17 airports had implemented CUSS (Behan 2006).

From early 2006 to early 2007, the number of implementa-

tions increased to 62. Similar interest is being shown with

other common use technologies.

One airport that was interviewed, Salt Lake City, stated

that it had determined that it was not in the best interest of the

airport to pursue common use. The main reason given was

that Delta Airlines accounted for 80% of its flight operations.

The airport noted that, as it looks toward the future and con-

struction of a new terminal, it may reconsider common use.

13

As airports and airlines move along the common use contin-

uum, it is important that they understand the advantages and

disadvantages associated with common use. Although the

common use model is implemented at airports, airlines have

a high stake in the changes as well. Changes may affect all

facets of airport operations including lease structures, oper-

ating procedures, branding, traveler way-finding, mainte-

nance, and software applications. Therefore, although the

implementation of common use occurs at the airport, the air-

port should take into consideration the impact of common

use systems on the airlines that service the market. More of

this will be discussed in later sections of this document.

ADVANTAGES OF COMMON USE

The greatest benefit driving common use in airports is more

efficient use of existing airport space. Other benefits include

improved traveling options for passengers and reduced capi-

tal expenditures for airports and airlines. In New York’s JFK

International Airport, Terminal 4 is privately operated and

currently has 16 gates. The terminal is expandable by up to

42 gates. With just the current 16-gate configuration, Terminal

4 is able to support 50 different airlines. A typical domestic

U.S. terminal without common use would only be able to