Residential Carshare Study for

the New York Metropolitan Area

Final Report | Report Number 20-03 | February 2020

NYSERDA’s Promise to New Yorkers:

NYSERDA provides resources, expertise,

and objective information so New Yorkers can

make confident, informed energy decisions.

Mission Statement:

Advance innovative energy solutions in ways that improve New York’s economy and environment.

Vision Statement:

Serve as a catalyst – advancing energy innovation, technology, and investment; transforming

New York’s economy; and empowering people to choose clean and ecient energy as part

of their everyday lives.

Residential Carshare Study for the New York

Metropolitan Area

Final Report

Prepared for:

New York State Energy Research and Development Authority

New York, NY

Robyn Marquis, PhD

Project Manager, Clea

n Transportation

Prepared by:

WXY Architecture + Urban Design

New York, NY

Adam Lubinsky, PhD, AICP

Managing Principal

Amina Hassen

Associate

Raphael Laude

Urban Planner

with

Barretto Bay Strategies

New York, NY

Paul Lipson

Principal

Luis Torres

Senior Consultant

and

Empire Clean Cities

NYSERDA Report 20-03 NYSERDA Contract 114627 February 2020

ii

Notice

This report was prepared by WXY Architecture + Urban Design, Barretto Bay Strategies, and Empire

Clean Cities in the course of performing work contracted for and sponsored by the New York State

Energy Research and Development Authority (hereafter the "Sponsors"). The opinions expressed in

this report do not necessarily reflect those of the Sponsors or the State of New York, and reference to any

specific product, service, process, or method does not constitute an implied or expressed recommendation

or endorsement of it. Further, the Sponsors, the State of New York, and the contractor make no warranties

or representations, expressed or implied, as to the fitness for particular purpose or merchantability of any

product, apparatus, or service, or the usefulness, completeness, or accuracy of any processes, methods, or

other information contained, described, disclosed, or referred to in this report. The Sponsors, the State

of New York, and the contractor make no representation that the use of any product, apparatus, process,

method, or other information will not infringe privately owned rights and will assume no liability for any

loss, injury, or damage resulting from, or occurring in connection with, the use of information contained,

described, disclosed, or referred to in this report.

NYSERDA makes every effort to provide accurate information about copyright owners and related

matters in the reports we publish. Contractors are responsible for determining and satisfying copyright or

other use restrictions regarding the content of the reports that they write, in compliance with NYSERDA’s

policies and federal law. If you are the copyright owner and believe a NYSERDA report has not properly

attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, please email print@nyserda.ny.gov

Information contained in this document, such as web page addresses, are current at the time

of publication.

Preferred Citation

New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA). 2019. “Residential Carshare

Study for New York Metropolitan Area,” NYSERDA Report Number 20-03. Prepared by WXY

Architecture + Urban Design, Barretto Bay Strategies and Empire Clean Cities.

nyserda.ny.gov/publications

iii

Abstract

Residential Carshare–New York Metro examines the feasibility of a carshare program business model

that deploys electric vehicles (EV) among the vehicle fleet mix, with deployment in different residential

markets, including low- and moderate- income (LMI) housing developments. “Residential carshare”

differs from many current market offerings in that it proposes carshare vehicles at multifamily residences

for the exclusive use of building residents, ensuring greater certainty to building residents of vehicle

availability. Examining New Rochelle, White Plains, and Yonkers as target areas for residential

carshare, this study employed the expertise of project partners, market analysis, and a pro forma to

assess the feasibility of the business model. The study finds that the convergence of three emerging

trendlines—new multifamily development, evolving personal mobility preferences, and generational

transition—has positioned Westchester County as an ideal testbed for EV carsharing. Nevertheless,

a cost premium associated with EV deployment, largely untested demand among LMI consumers, and

the limitations placed on the size of the market due to exclusivity of use all conspire against a rapid

return on investment and a clear path to profitability. To achieve success, a clear and compelling

alignment of interests between city government, the development community, and carsharing

organizations will be required.

Keywords

Residential carshare, carshare, car share, car-share, electric vehicles, EV, ZEV, BEV, PHEV, municipal

fleet, mobility, shared mobility, equitable mobility, sustainable transportation, sustainability, carbon,

service, development, real estate, housing, pro forma, business model, policy, New York, New York

State, Westchester County, Westchester, Yonkers, New Rochelle, White Plains

iv

Table of Contents

Notice .........................................................................................................................................ii

Preferred Citation ......................................................................................................................ii

Abstract ....................................................................................................................................iii

Keywords ..................................................................................................................................iii

List of Figures ........................................................................................................................viii

List of Tables ..........................................................................................................................viii

Acronyms and Abbreviations .................................................................................................ix

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ ES-1

1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................1

1.1 The Shared Mobility Landscape ............................................................................................... 1

1.2 What is Carshare?.................................................................................................................... 2

1.3 Benefits of Carshare ................................................................................................................. 3

1.3.1 Reduced Car Ownership ................................................................................................... 3

1.3.2 Reduce Vehicle Miles Traveled and Greenhouse Gas Emissions ...................................... 3

1.3.3 Transportation Equity ........................................................................................................ 3

1.3.4 Cost Savings .................................................................................................................... 4

1.3.5 Appeal to Shifting Consumer Preferences ......................................................................... 4

1.4 Obstacles for Shared Mobility ................................................................................................... 5

1.5 The Residential Carshare Opportunity ...................................................................................... 5

2 Westchester County

..........................................................................................................7

2.1 Population Growth and Density ................................................................................................ 9

2.1.1 Carshare and the Built Environment ................................................................................ 11

2.2 Demographic Trends .............................................................................................................. 12

2.2.1 Median Income ............................................................................................................... 12

2.2.2 Education ....................................................................................................................... 14

2.2.3 Diversity ......................................................................................................................... 16

2.3 Responding to Demographic Trends....................................................................................... 17

2.3.1 Baby Boomers ................................................................................................................ 17

2.3.2 Millennials ...................................................................................................................... 19

2.4 Mobility and the Built Environment .......................................................................................... 20

2.4.1 Car Ownership ............................................................................................................... 20

2.4.2 Electric Vehicles and Charging Infrastructure .................................................................. 23

2.4.3 Public Transit .................................................................................................................. 25

v

2.4.4 Taxis and Limousines ..................................................................................................... 27

2.4.5 Transportation Network Companies ................................................................................ 27

2.4.6 Walking and Biking ......................................................................................................... 28

2.4.7 The Potential for Carshare in the Evolving Mobility Landscape ........................................ 29

2.5 Target City Profiles ................................................................................................................. 29

2.5.1 New Rochelle ................................................................................................................. 29

2.5.2 White Plains ................................................................................................................... 30

2.5.3 Yonkers .......................................................................................................................... 31

3 The Market for Residential Carshare in Westchester ....................................................33

3.1 User Profiles .......................................................................................................................... 33

3.1.1 Miscellaneous Errands and Nonwork Trips ..................................................................... 33

3.1.2 School Parents ............................................................................................................... 33

3.1.3 Downsizing Seniors and New Empty Nesters .................................................................. 34

3.1.4 Building Management Personnel, Office Workers, and Home-Based Business Owners ... 34

3.1.5 Shift Workers .................................................................................................................. 35

3.2 Market Research .................................................................................................................... 36

3.2.1 Multifamily Rental Construction in Westchester ............................................................... 36

3.2.2 White Plains Multifamily Rental Construction................................................................... 36

3.2.3 New Rochelle Multifamily Rental Construction ................................................................ 37

3.2.4 Yonkers Multifamily Rental Construction ......................................................................... 38

3.3 Identifying Areas of Opportunity .............................................................................................. 38

3.4 Site Analysis .......................................................................................................................... 43

3.4.1 The Community Builders’ Ridgeway Apartments in Yonkers............................................ 44

3.4.1.1 Schoolhouse Terrace (33 and 43 Ashburton Avenue, Yonkers)....................................... 45

3.4.1.2 188 Warburton ............................................................................................................... 45

3.4.1.3 The Villas at The Ridgeway ............................................................................................ 45

3.4.2 L + M and Wilder Balter's 14 Lecount Place, New Rochelle ............................................. 45

3.4.3 Bozzuto Development's 15 Bank Apartments in White Plains .......................................... 46

3.4.4 Wilder Balter's Chappaqua Crossing, Chappaqua ........................................................... 47

4 Carshare Precedents .......................................................................................................49

4.1 Electric Vehicle Carshare Precedents ..................................................................................... 49

4.1.1 Principal Operators ......................................................................................................... 49

4.1.1.1 Bolloré Group ................................................................................................................. 49

4.1.1.2 Car2Go .......................................................................................................................... 49

4.1.1.3 SelfDrive ........................................................................................................................ 50

vi

4.1.1.4 BMW/ReachNow/DriveNow ............................................................................................ 50

4.1.1.5 GM/Maven ..................................................................................................................... 50

4.1.2 Principal Markets—International ..................................................................................... 51

4.1.2.1 Paris, France .................................................................................................................. 51

4.1.2.2 Amsterdam, Netherlands ................................................................................................ 51

4.1.2.3 Den Bosch, Netherlands ................................................................................................. 51

4.1.2.4 Copenhagen, Denmark................................................................................................... 51

4.1.2.5 Singapore ....................................................................................................................... 52

4.1.2.6 Dubai, United Arab Emirates .......................................................................................... 52

4.1.2.7 London, United Kingdom ................................................................................................ 52

4.1.2.8 Cheng Du, China ............................................................................................................ 52

4.1.3 Principal Markets—Domestic .......................................................................................... 53

4.1.3.1 Indianapolis, Indiana ....................................................................................................... 53

4.1.3.2 Portland, Oregon ............................................................................................................ 53

4.1.3.3 Los Angeles, California ................................................................................................... 53

4.1.3.4 Chattanooga, Tennessee ............................................................................................... 53

4.1.3.5 Seattle, Washington ....................................................................................................... 54

4.1.4 Electric Vehicle Carshare Precedents in Low- to Moderate-Income Communities ............ 54

4.1.5 Electric Vehicle Carsharing—Challenges ........................................................................ 55

4.1.5.1 Lack of Suitable Infrastructure ........................................................................................ 55

4.1.5.2 High Costs Associated with Bringing Power to Charging Stations ................................... 55

4.1.5.3 Unfamiliarity with Charging Equipment ............................................................................ 55

4.1.5.4 Costs and Competing Services ....................................................................................... 56

4.1.6 Electric Vehicle Carsharing—Opportunities ..................................................................... 56

4.1.6.1 The Autonomous Future ................................................................................................. 56

4.1.6.2 Suitability of Electric Vehicles for Carsharing .................................................................. 57

4.1.6.3 Bridging Transit Divides .................................................................................................. 57

4.2 Municipal Fleets and Electric Vehicle Carsharing .................................................................... 57

4.2.1 New Rochelle ................................................................................................................. 58

4.2.2 White Plains ................................................................................................................... 59

4.2.3 Yonkers .......................................................................................................................... 59

4.2.4 County of Westchester.................................................................................................... 60

5 The Feasibility of Residential Carshare..........................................................................61

5.1 Customer Segments ............................................................................................................... 61

5.2 Value Proposition ................................................................................................................... 62

vii

5.2.1 Value Proposition for Carshare Customers ..................................................................... 62

5.2.2 Value Proposition for the Broader Public ......................................................................... 62

5.3 Customer Channels and Relationships ................................................................................... 63

5.4 Key Assumptions ................................................................................................................... 63

5.4.1 Development and User Assumptions .............................................................................. 63

5.5 Key Activities and Partners ..................................................................................................... 64

5.6 Cost Structure ........................................................................................................................ 65

5.7 Revenue Streams................................................................................................................... 67

5.7.1 Two-Tiered Pricing Model ............................................................................................... 67

5.7.2 Other Revenue ............................................................................................................... 68

5.7.3 Funding Gap................................................................................................................... 68

5.8 Pro Forma .............................................................................................................................. 68

6 Discussion ........................................................................................................................70

6.1 Aligning Incentives ................................................................................................................. 70

6.2 The Residential Carshare Opportunity in Westchester ............................................................ 70

6.3 Policy Implications .................................................................................................................. 71

6.3.1 Case Studies .................................................................................................................. 72

6.3.1.1 Austin, Texas ................................................................................................................. 72

6.3.1.2 Vancouver, British Columbia ........................................................................................... 72

6.3.1.3 San Francisco, California ................................................................................................ 72

6.3.2 Fleet Sharing .................................................................................................................. 73

6.4 Equity and Carsharing ............................................................................................................ 74

6.4.1 The Equity Policy Imperative ........................................................................................... 74

6.4.1.1 Spatial Factors and Equity .............................................................................................. 76

6.4.1.2 Temporal Factors and Equity .......................................................................................... 77

6.4.1.3 Economic Factors and Equity ......................................................................................... 77

6.4.1.4 Mobility Impairment and Equity ....................................................................................... 80

6.4.1.5 Social Factors and Equity ............................................................................................... 80

6.4.1.6 Equity Facilitators and Intermediaries ............................................................................. 81

6.4.1.7 Ensuring Equity: Recommendations ............................................................................... 82

6.5 Summary of Benefits .............................................................................................................. 82

7 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................84

Appendix: Additional Tables and Figures ........................................................................... A-1

Endnotes ............................................................................................................................ EN-1

viii

List of Figures

Figure 1. Shared Mobility Landscape ..........................................................................................1

Figure 2. Carshare Models ..........................................................................................................2

Figure 3. Complementary Mobility Options ..................................................................................6

Figure 4. Westchester County Up-County and Down-County Population Density .......................8

Figure 5. Westchester County Population Rate of Change (2010–2016).....................................9

Figure 6. Population Density in Westchester County .................................................................10

Figure 7. Median Household Income in Westchester County ....................................................13

Figure 8. Median Income by Educational Attainment in Westchester County ............................15

Figure 9. Vehicle Ownership by Educational Attainment in Westchester County .......................16

Figure 10. Vehicle Ownership by Household Income ................................................................21

Figure 11. Household Car Ownership .......................................................................................22

Figure 12. Electric Vehicle Registration in New York State Counties .........................................23

Figure 13. Electric Vehicle Growth in Westchester County ........................................................24

Figure 14. Charging Ports in Westchester County .....................................................................25

Figure 15. Residential Carshare Suitability Metrics in Westchester County ...............................40

Figure 16. Areas of Opportunity for Residential Carshare in Westchester County .....................42

Figure 17. Potential Frequent Destinations near The Ridgeway Apartments .............................43

Figure 18. Ridgeway Apartments in Yonkers ............................................................................44

Figure 19. Lecount Place Development in New Rochelle ..........................................................45

Figure 20.15 Bank Apartments in White Plains .........................................................................46

Figure 21. Chappaqua Crossing Development in Chappaqua ...................................................47

Figure 22. Pro Forma Summary Slide Preview..........................................................................69

List of Tables

Table 1. Comparison of Westchester County Population and Residential Density ....................11

Table 2. Median Household Quintiles for Westchester County ..................................................14

Table 3. Racial Makeup of Westchester County ........................................................................17

Table 4. Residential Carshare Evaluation Criteria .....................................................................39

ix

Acronyms and Abbreviations

A amps

BEV battery-electric vehicle

EV electric vehicle

EVSE electric vehicle supply equipment

ft feet

GHG greenhouse gas

ICE internal combustion engine

kW kilowatt

kWh kilowatt-hour

PEV plug-in electric vehicle

PHEV plug-in hybrid electric vehicle

POV privately owned vehicle

sf square foot, square feet

TNC Transportation Network Company

V volts

VMT vehicle miles traveled

ZEV zero-emissions vehicle

ES-1

Executive Summary

A typical car is parked 95% of the day,

1

which suggests that many car owners could address their

mobility needs through a shared vehicle. Residential Carshare–New York Metro examines the feasibility

of a carshare program business model that deploys electric vehicles (EV) among the vehicle fleet mix,

with deployment in different residential markets, including low- and moderate-income (LMI) housing

developments. The study leverages expertise of project partners in New Rochelle, White Plains, and

Yonkers as target areas for the study.

The idea behind “residential carshare” differs from many current market offerings in that it proposes

carshare vehicles at multifamily residences for the exclusive use of building residents, ensuring greater

certainty to building residents of vehicle availability. Using zero-emission vehicles (ZEV) as carshare

vehicles can increase mobility without increasing overall greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Policymaking is especially important for support in the growth of the program—public policy that

facilitates expanded mobility options in LMI communities and that trades potentially outdated parking

requirements for EV carsharing implementation is a promising strategy to stimulate demand. The

following research questions guided the research team in identifying a feasible and scalable program

and deployment model for residential carshare:

• What are the challenges to creating residential carshare, including start-up and operational

costs for this program?

• What are the optimal conditions at multifamily residential developments to support a

successful carshare program?

• How can a residential carshare program be leveraged to change public policy around parking

requirements? Conversely, how can policymaking most effectively incentivize EV carsharing

in multifamily residential settings?

• Can a supportive ecosystem of automakers, carshare operators, and residential developers

alone bring about the widespread proliferation of this program, or, are other levers required?

• What are the qualitative and, when possible to establish, quantitative impacts of a residential

carshare program in terms of carbon emissions saved, reduced car ownership, improvements

to mobility options (particularly in the LMI communities), and developer interests?

• Is there currently a residential carshare business model that includes LMI communities

to be financially viable?

• How can carshare utilization be optimized to ensure program viability?

1

1 Introduction

1.1 The Shared Mobility Landscape

Shared mobility is the ensemble of transportation modes where a vehicle is shared by many users,

accessed on an as-needed basis, and does not follow a regular schedule or route. Shared mobility is

typically used to refer to low-capacity shared modes such as carsharing, bike sharing, microtransit,

ride hailing, and ridesharing services (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Shared Mobility Landscape

Shared mobility services promise an alternative to personal vehicle ownership. A sufficiently economical

and robust network of shared mobility services could, in combination, offer the flexibility of privately-

owned vehicles (POVs) without the associated challenges of ownership (e.g. cost, parking, maintenance).

Shared mobility services come with the substantial benefits of reducing congestion and decreasing over

all vehicle miles traveled (VMT); by sharing vehicular trips, or replacing them entirely by walking or

2

biking, roads will flow more smoothly, and reduced emissions can improve community health. Shared

modes promise to improve asset utilization, too; using smaller fleets to fulfill transportation needs means

fleet vehicles can be replaced more regularly, keeping pace with improvements in fuel efficiency and

design, and reducing the total number of vehicles produced.

2

1.2 What is Carshare?

Carshare is a service that allows users to access a vehicle for a short period of time, usually by the hour

or minute, in an effort to utilize vehicles more effectively. Figure 2 shows different models of carshare

available to users.

Figure 2. Carshare Models

The United States represents three-quarters of North America’s carshare market.

3

Carshare membership

has ballooned from less than 180,000 members in 2007 to more than 1.4 million members in 2017.

4

These

figures are even higher—4.8 million members—when an ever expanding peer-to-peer carsharing network

is considered.

5

Carsharing enables drivers to conveniently access a vehicle on a short-term basis and avoid

3

the high cost of owning and maintaining a personal vehicle. The costs of vehicle ownership are especially

high in cities and on college campuses, where vehicle ownership is typically low. As such, carshare is

especially popular in these markets.

6

1.3 Benefits of Carshare

1.3.1 Reduced Car Ownership

Carsharing has potential to substantially reduce POV ownership, particularly in urban markets. Research

by Susan Shaheen at University of California (UC) Berkeley’s Transportation Sustainability Research

Center (TSRC) suggests that one shared car under the round-trip model replaces nine to 13 POVs. One

shared car in a free-floating model replaces seven to 11 POVs (Figure 2).

7

1.3.2 Reduce Vehicle Miles Traveled and Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Shaheen’s research suggests that carshare caused a 1.3% to 5.0% reduction in VMT in urban areas,

correlating with estimated 0.4% to 2.1% reduction in GHG emissions. Households that adopt carshare

see even more substantial savings: households that sell their POV and replace it with carshare may see

annual VMT reduction of 27% to 43% with an associated 34% to 41% reduction in annual household

GHG emissions.

8

1.3.3 Transportation Equity

Overall, low-income Americans spend a higher share of their discretionary income on transportation

and are often unable to afford a POV. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure

Survey indicates that in 2015 and 2016, residents across the U.S. making less than the median

income—$56,277 and $57,617, respectively

9

—spent 22% of their income on transportation while

those making more than median income spent only 12% of their income on transportation.

10

In line

with this finding, the costs of owning a POV are particularly burdensome for LMI households, who

tend to have much less access to a personal vehicle. Those who have a POV often lack the savings for

unexpected repairs,

11

or routine maintenance. Volatility in gas prices can further burden households

on a tight budget. Carshare can help reduce the mobility gap between high- and low-income

households, decreasing expenses for cost-burdened households and, in particular, increasing

LMI individuals’ mobility.

4

1.3.4 Cost Savings

New York City has the highest costs associated with owning and maintaining a POV in the U.S., around

$19,000 annually

12

compared with the national average of around $10,000 per year.

13

Costs for ownership

in Westchester County, where the three cities included in this study are located, are likely to be some

what higher than the national average. This is especially the case in Westchester's cities because most

of the costs associated with owning and maintaining a POV come from parking, and the cities in

Westchester, due to their proximity to New York City, tend to have higher parking fees than the national

average. Shaheen’s research found that households that sell a POV and substitute their trips with carshare

and other modes saw monthly household savings of $154 to $435.

14

These savings could represent more

than 7.5% of household transportation costs for families in the bottom decile, whose annual incomes

were less than $16,500 between 2012 and 2016.

15

1.3.5 Appeal to Shifting Consumer Preferences

It is increasingly common for consumers in dense metro areas to relinquish car ownership. A 2015

Deloitte study revealed that just 64% of Generation Y (also called “millennials”

16

) consumers in

the U.S. view the personal car as a preferred mode of transport.

17

According to the Pew Research

Center, millennials are youth born between 1981 and 1996. The U.S. millennial population now

numbers 83.1 million nationwide representing more than one quarter of the nation’s population,

surpassing the baby boomer population and making them the largest generation.

18

Rapidly evolving

technology, cultural, and economic factors have been cited in consumer studies as key forces

bolstering the carsharing movement, especially among urban millennials.

Major auto original equipment manufacturers (OEM) have introduced carsharing as a way of staying

competitive among consumer groups that are buying fewer cars. Auto OEMs recognize that carsharing

platforms can build brand awareness among sought-after millennials and start to familiarize consumers

with electric drive transportation. Both General Motors (GM) and BMW Group have carsharing

services using new plug-in electric vehicle (PEV) models in dense U.S. and European metros.

According to Navigant Research, the incorporation of EVs in carsharing services is projected

to grow as automakers continue to diversify their fleets with electric drive technology.

5

1.4 Obstacles for Shared Mobility

American attitudes towards car ownership are a big obstacle limiting the uptake of shared modes.

Cars have been the dominant transportation mode for most Americans for well over a century. In 2016,

76% of Americans drove to work alone in a car; in Westchester County the percentage was 58.2%.

19

Not only are cars convenient, but they also hold enormous prominence in American culture, affection,

status, and understandings of freedom. Although the U.S. saw a dip in VMT in 2014, VMT has risen

sharply since 2016 and is now back to pre-recession levels.

20

Younger generations—notoriously

millennials—may be opting for other modes of transportation, although evidence of this explanation

is more tenuous.

21

1.5 The Residential Carshare Opportunity

No mode of transportation offers more flexibility than POVs; cars can relatively cheaply serve trips

of any length, along any route, and at any time. Residential carshare—integrating carshare vehicles

in garages and lots of multifamily buildings for use by building residents and staff—is an exciting

opportunity to shift American attitudes about getting around. Bringing carshare into residential

developments would increase the visibility and convenience of carshare for building residents.

Matching the flexibility of privately owned cars with more sustainable transportation substitutes

is challenging; however, a combination of modes—public transportation, carshare, for-hire vehicles,

walking, and biking—could provide households with sufficient flexibility at a lower cost and with

fewer emissions (Figure 3).

6

Figure 3. Complementary Mobility Options

7

2 Westchester County

Westchester County is located north of New York City in the Hudson Valley, bordering Putnam

County to the north, Rockland County to the west, Bronx County to the south and the Long Island

Sound to the east. Westchester is characterized by a marked difference between its northern and

southern halves (up-county and down-county).

22

Westchester’s southern half hosts more jobs and

people, who live more densely, closer to public transit, and are more diverse. The county’s northern

half, by contrast, hosts more open space, lower population density, greater prevalence of single-family

homes, and higher medium income (Figure 4). The far-southern end of Westchester is primarily urban,

where the county’s configuration of buildings in relation to streets is consistent with that of its densely

populated southern neighbor, the Bronx. Northern Westchester, by contrast, is sparsely populated and

hosts large forested areas and water bodies.

8

Figure 4. Westchester County Up-County and Down-County Population Density

Data: ACS 2016 5-Year, Westchester County GIS

9

2.1 Population Growth and Density

Westchester County, the seventh most populous county in New York State after four New York City

counties and both of Long Island's counties, with an estimated 974,542 people as of 2016,

23

is growing

and priming itself for further growth and development. Westchester grew 2.7% from 2010 to 2016, a

higher growth rate than New York State’s average 0.18% growth over the same period (Figure 5).

24

Much of that growth has been concentrated in the county’s six cities, where mayors and developers

have shown an interest in revitalizing ailing downtowns to accommodate changing resident profiles

and preferences.

Population growth in Westchester has been most pronounced along major transit routes, including

three Metro-North lines, Amtrak Northeast regional service, and the Bee-Line Bus Service. More than

65% of residents live within 0.5 miles of a bus line,

25

and there has been a continuing trend emphasizing

transit-oriented developments.

Figure 5. Westchester County Population Rate of Change (2010–2016)

Data: ACS 2016 5-Year

10

Population density is an important indicator for carshare success. County-wide, population density

was 2,264 persons per square mile.

26

However, there is tremendous variation in population density

across Westchester, as seen in Figure 6. Only 30% of residents live up-county where the population

density is only about three persons per acre (or one household) while 70% of the Westchester population

lives down-county, with an average population density of nine persons per acre (or three households).

By comparison, the average suburban density nationwide is three households per acre.

27

Figure 6. Population Density in Westchester County

Data: ACS 2016 5-Year

11

Around 43% of Westchester residents live in the county’s four biggest and densest municipalities:

Yonkers, New Rochelle, Mount Vernon, and White Plains, in that order (Table 1). Westchester’s

densest municipality, Yonkers, has an average 11,150 persons per square mile. Together, these data

suggest that Westchester’s largest southern cities present the greatest opportunity for residential

carshare, on account of their high-population densities.

Table 1. Comparison of Westchester County Population and Residential Density

Data: ACS 2016 5-Year

New

Rochelle

White

Plains

Yonkers

Westchester

Residential Population

79,557 58,241 200,807 974,542

Population Percent Change (2010–2017)

3.2% 2.4% 2.5% 2.7%

Land Area (Square Miles)

10.4 9.8 18.0 430.5

Residential Density (per sq. mile)

7,687 5,961 11,150 2,264

Residential Density (per acre)

12.0 9.3 17.4 3.5

2.1.1 Carshare and the Built Environment

Density is an essential ingredient for successful carshare and shared mobility in general. Urban markets

have quickly adopted carshare in the U.S. and abroad. Analysis of shared mobility in cities across the U.S.

has found that shared mobility options do well in dense urban areas with high-median income and low-car

ownership.

28

The Shared Use Mobility Center (SUMC) has found that moderately dense neighborhoods,

in particular, hold great opportunity for cities looking to reduce car ownership since they still have a level

of car dependence while also offering many alternative mobility options.

29

When these neighborhoods are

close to major job and transit hubs, that opportunity is even greater.

Further research by SUMC suggests that drivers are also more likely to sell or postpone purchasing a car

if they have access to more modes of transportation.

30

Filling Westchester’s service gaps, particularly the

first and last mile connections, can provide residents with more mobility while reducing the number of

cars on the road.

12

2.2 Demographic Trends

2.2.1 Median Income

Westchester County has a high-median household income of $86,226 in 2016, far above the New York

State median income of $60,741 and the U.S. national median of $57,617 in 2016 dollars.

31

A closer

look at income by municipality reveals a wide range across the county (Figure 7). At the higher end of

the spectrum is Scarsdale, with median income exceeding $250,000,

32

Bronxville ($250,000), New Castle

($204,500), Pound Ridge ($188,400), and North Castle ($177,568). All have more than double the state

median in 2016 dollars.

33

At the lower end of the spectrum are municipalities including Mount Vernon

($51,886) and Peekskill ($55,453) with median incomes below both State average and national average.

34

13

Figure 7. Median Household Income in Westchester County

Data: ACS 2016 5-Year

14

As with population density, the Westchester up-county/down-county divide is pronounced when looking

at income distribution. Table 2 shows that median household income is 138% greater in the Westchester

up-county census tracts. Areas in up-county Westchester tend to have higher median household income

on average, while both highest and lowest earning areas in Westchester are located down-county. These

figures suggest that there is a greater wealth disparity down-county while northern Westchester is more

middle-class.

Table 2. Median Household Quintiles for Westchester County

Data: ACS 5-Year 2016

Median Household Income Quintiles

min 1 2 median 3 4 max

Down-County

$18,482 $48,215 $69,476 $76,183 $83,634 $130,046 >$250,000

Up-County

$35,813 $68,632 $93,006 $105,256 $119,051 $141,326 $237,500

ratio 194% 142% 134% 138% 142% 109% 95%

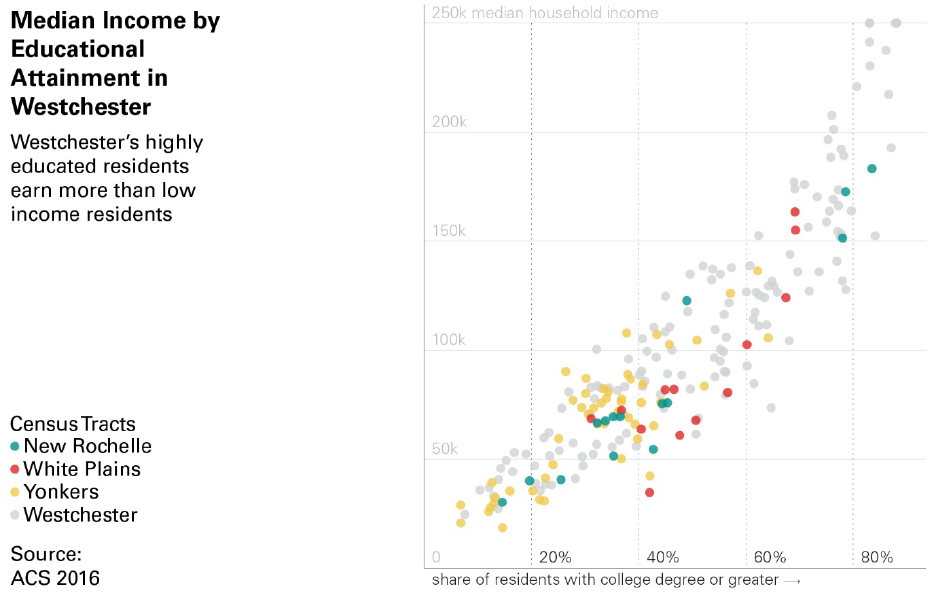

2.2.2 Education

Westchester County has one of the highest education rates in New York State, with 47% of the population

25 years or older holding a bachelor’s degree or postgraduate degree.

35

Educational attainment varies

across the county. Fewer than 32% of residents in Yonkers have a bachelor’s or postgraduate degree, a

rate 20% lower than the New York Metro Area average. By contrast, nearly half of residents in White

Plains (49%) and New Rochelle (47%) have obtained a bachelor’s degree or greater. In Westchester,

household income and educational attainment are strongly correlated (R=0.89), as shown in Figure 8.

15

Figure 8. Median Income by Educational Attainment in Westchester County

Data: ACS 2016 5-Year

Westchester residents are more likely to own a car if they have a bachelor’s degree or greater

(Figure 9). Although less strongly correlated than income and vehicle ownership or income and

educational attainment, educational attainment and vehicle ownership are strongly correlated

(R=0.71), particularly in New Rochelle.

16

Figure 9. Vehicle Ownership by Educational Attainment in Westchester County

Data: ACS 2016 5-Year

Carshare users have a very high level of educational attainment: 81% of carshare users have a

bachelor’s degree or more advanced degree, according to a 2008 survey.

36

According to the same

survey, 41% of users hold an advanced degree, and just 2% of users do not have any college education.

37

2.2.3 Diversity

Westchester is not only growing in terms of population size, but it is also diversifying (Table 3).

The county is very diverse, with 45% non-White residents. Every municipality in Westchester County

recorded a gain in Hispanic and Latino-identifying populations between the 2000 and 2010 Census

years,

38

a gain of nearly 62,000 residents. As stated on the Westchester County website, Hispanic

and Latino populations “now constitute nearly 22% of the total population and are a majority in Port

Chester (59%) and Sleepy Hollow (51%).”

39

Westchester Black and Hispanic or Latino populations disproportionately live in the county’s densest

areas down-county, together representing 43% of its population. Up-county Westchester is less diverse

than down-county and the national average: only around one in three of its residents are non-White.

17

Table 3. Racial Makeup of Westchester County

Data: ACS 2016 5-Year

Race

Total

Population

Density

(per acre)

White Black Asian

Some

Other

Two Or

More

Latino

Down-County

332,947 113,131 42,577 3,013 11,864 172,965 676,497 8.56

Up-County

198,056 17,070 12,295 640 5,247 55,461 288,796 1.39

2.3 Responding to Demographic Trends

According to the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies in the America’s Rental Housing 2017

report, changing demographics are driving demand for rental housing and are increasing pressure on

affordability in markets across the U.S.

40

The market has expanded to new demands for rental housing

with new options for high-end and single-family housing. However, the market has fallen behind in

providing adequate affordable options, which leads to increasing numbers of individuals who are rent

burdened, spending more than 30% of their discretionary income on rent.

Demographics trends and changing resident preferences in home and mobility options has

municipalities across Westchester moving toward investing in their downtowns, bolstering walkability,

mixed-use downtowns, multifamily housing, and mobility amenities. The result has been a multifamily

housing permitting and construction boom, with approvals for new housing units not seen since before

the Great Recession (2007–2009). There is an estimated 16,000 new rental units under construction

or in the planning stages to be completed in the near future in Westchester County, representing an

11% increase in the number of rental units that existed in 2017; over the last five years this number

had grown less than 1%.

41

2.3.1 Baby Boomers

Westchester County is getting older: the county median age rose from 37.6 in 2000 to 40 in 2010 Census

years. According to the U.S. Census, “baby boomers” are individuals born in the U.S. between mid-1946

and mid-1964.

42

Previously the largest generation, baby boomers are now reaching retirement age as they

enter their sixties and seventies.

18

As residents in the county get older, there has been an increasing need for additional multifamily options

to allow baby boomers to downsize to more manageable and/or affordable options without leaving the

county. Unlike single-family and smaller multifamily housing stock, larger multifamily buildings tend

to have accessible design features, such as elevators, wide hallways and doors, and other features

attractive to households with mobility challenges that become more common in older age. Harvard’s

Joint Center for Housing Studies 2017 report on the rental housing market in the U.S predicts that

baby boomers and millennials will increasingly generate renter households across the country.

43

Baby boomers, who started driving at a young age, were the first truly hypermobile generation. They

have always been interested in cars and have relied on them for decades, making cars a central component

of their definition of mobility. The challenge is for them to understand that private car ownership is not

the only option for comfortable mobility, and shared car ownership can fulfill their needs while being

more economical and beneficial. The baby boomer generation has been responsible for the growth in

travel over the past 40 years; according to an AARP study, the number of VMT grew at twice the rate

of population growth, and travel rates more than doubled from 1969–2009.

44

Some of this growth in

travel can be attributed to a historic shift from single-earner to dual-earner households that helped define

new patterns of commuting among the generation. In 1969, only 30% of two-adult households had two

or more vehicles, a percentage that more than doubled in forty years to 77% in 2009.

45

More recently,

there has been a turning point and reversal of the trend of year-over-year increases in VMT; on a per

capita basis, Americans of all ages are traveling fewer miles in 2009 compared to 2001. Many factors

play a role in declining VMT, including increasing and variable gas prices, unemployment, and an

expansion of travel modes.

46

As baby boomers enter retirement stages in their lives, they generally have overall lower travel rates,

suggesting that many of their driving needs could be met with alternative modes of travel, including

carshare. “No single solution will address the myriad mobility challenges of an aging population,”

writes AARP, “…A variety of individual choices, as well as public, private, and nonprofit investment

tailored to the needs and desires of boomers, will help them sustain their quality of life as they age.”

47

Residential carshare offers an important opportunity for two-car households to downsize to one-car

households that would complement changing living and driving patterns among boomers. According

to the AARP study, medical related trips is one travel pattern that has skyrocketed as the baby boomers

age and is expected to further increase.

19

2.3.2 Millennials

As Westchester is getting older, attracting younger generations has become a priority for many mayors

across the county. According to the Pew Research Center, millennials are youth born between 1981 and

1996. The U.S. millennial population now numbers 83.1 million nationwide representing more than one

quarter of the nation’s population, surpassing the baby boomer population and making them the largest

generation.

48

Millennials also represent more than a third of the total workforce in the U.S.

49

Thus,

millennials are an important market segment that is anticipated to increase demand for rental housing

over the next decade.

As Westchester residents get older, many municipalities are looking to lure millennials and young

professionals to revitalize their tax base and call Westchester home. Admiral Real Estate and

CoStar Group analysis found that millennials constitute 35% to 45% of the apartment rental

market in Westchester.

50

Millennial living preferences and spending habits differ greatly from previous generations. While

older generations tended toward decentralized and car-dependent suburban living and homeownership,

millennials tend to favor dense, walkable, mixed-use communities with easy access to services

(restaurants, activities), jobs, recreation, and public transit. Another important shift in generational

trends is that millennials tend to take a more pragmatic and nuanced view towards homeownership and

car ownership. Since 2004, there has been a sharp decline in the homeownership rate. Proliferation of

carshare and rideshare services have made prolonging or foregoing car ownership an appealing option,

one that eliminates added expense and hassle.

In a Building Owners and Managers Association organized panel discussion with the mayors of

Yonkers, White Plains, and New Rochelle in 2017, each of the three mayors stated that attracting

and retaining young professionals was central to the future success of his/her city.

51

This is especially

important since the county has seen a decline in the number of young people; the number of people

between the ages of 25 and 34 in Westchester County dropped by almost 8% from 2000 to 2016.

52

20

2.4 Mobility and the Built Environment

2.4.1 Car Ownership

The construction of the Bronx River Parkway in 1908, one of America’s first parkways design for cars,

has exerted tremendous influence on Westchester and its built form. Originally conceived for pleasure

drives, the Bronx River Parkway was part of an introduction to key innovations in freeway design such

as grade separation and limited access, heralding the extensive network of parkways, interstate highways,

and commercial arterials in Westchester today.

53

Cars are the dominant mode of transportation in Westchester and have greatly shaped land uses. Many

of the downtowns in the county host commercial corridors four or more lanes in width, flanked by low

buildings and large surface lots. The speed of the car makes it easy to live far from work, a convenience

that has facilitated the separation of residential and commercial uses in Westchester, in which low-density

suburbs surround moderately dense downtowns. Accordingly, Westchester’s built environment

encourages residents to make short trips by car rather than by other modes.

Nearly 95% of Westchester residents have access to a car. In 2016, there were 622,066 registered

standard vehicles in the county (the Department of Motor Vehicles of the State of California defines

“standard” as passenger vehicles that do not transport persons for hire

54

). This is about two cars for

every three residents.

Westchester’s cars are not evenly distributed across space or income bracket, however. In 2016

there were 49,680 households without access to a car, one in twenty in the county (ACS 2016).

These households are strongly concentrated around core commercial areas and rail stations,

generally living more densely.

The largest cities in the county—Yonkers, New Rochelle, Mount Vernon, and White Plains—have

lower rates of car ownership on average than their peer municipalities (Figure 11). The average household

in these cities owns 1.3 vehicles; outside these municipalities the average is 30% higher, at 1.7 vehicles.

Yonkers has especially low rates of vehicle ownership, where one in three households lack access to a

POV. Moreover, POV-owning households in the target cities are much less likely to own multiple cars.

In Westchester as a whole, 41% of POV-owning households own a single vehicle. By contrast, 47% to

53% of POV-owning households in New Rochelle, White Plains, and Yonkers only own a single vehicle.

21

At first glance this is encouraging, suggesting that proximity to services and/or transit are inversely

related to vehicle ownership. On closer inspection, we find that areas of low-vehicle ownership rates

tend also to have the lowest rates of median household income (Figure 10 and 11).

Figure 10. Vehicle Ownership by Household Income

Data: ACS 2016 5-Year

Residents in the target cities are less able to afford a vehicle. Remembering the general relation of

economic growth to VMT, it is likely that economic hardship is a stronger indicator of vehicle ownership

than proximity to transit or land use patterns in Westchester. Vehicle ownership is strongly correlated to

income in Westchester (R=0.80), especially in Yonkers (R=0.83), White Plains (R=0.83), and New

Rochelle (R=0.90).

Indeed, low-income census tracts for Yonkers, where annual median household income is less than

$47,000, between 40% and 61% of households lack access to a POV. This suggests that LMI individuals,

who are more likely to live in multifamily buildings in dense neighborhoods, are likely to benefit most

from access to a shared vehicle and present an ideal market for carshare.

22

Figure 11. Household Car Ownership

Data: ACS 2016 5-Year

23

2.4.2 Electric Vehicles and Charging Infrastructure

As of June 2018, 2,641 electric vehicles were registered in Westchester County, the third greatest

number among counties in New York State, according to New York State Department of Motor

Vehicles registrations data (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Electric Vehicle Registration in New York State Counties

Data: NYSDMV Vehicle Registrations, July 2018

This figure has room to grow. According to a report prepared by the Columbia Master of Science in

Sustainability Management Program, Westchester residents match the socioeconomic and political profile

of target EV buyers.

55

In line with this finding, EV sales across the county have been steadily increasing:

between 2012 and 2017, EV registrations in Westchester grew by 160% per year on average (Figure 13).

24

Figure 13. Electric Vehicle Growth in Westchester County

Data: NYSDMV Vehicle Registrations, July 2018

Factors that make EVs a more viable option include State and federal incentives,

56

decreasing prices for

EVs, improved battery technology, and access to charging infrastructure.

57

58

To encourage the uptake of

EVs in New York State, Governor Cuomo and NYSERDA introduced, and have recently expanded, the

program, which is driving the development of the county’s network of charging stations, as part of a plan

to reduce the State GHG emissions.

59

As of November 2019, there were more than 240 public access Level 2 EV charging ports located

throughout Westchester County.

60

These are primarily located in Westchester municipal centers along key

corridors. There are 28 ports in downtown White Plains, with an additional 22 ports accessible within 3

miles. With this infrastructure in place, White Plains is Westchester’s most EV-friendly city (Figure 14).

Westchester’s network of public access electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE) has the capacity to

support more use. Small fleets of shared EVs would not place significant burden on the network. With

access to charging infrastructure in a residential development, the vehicles in a shared electric fleet under

the round-trip model would likely have the range to satisfy user demands, placing little demand on the

Westchester EVSE network. However, given the additional capacity in Westchester’s existing charging

infrastructure, users might be further encouraged to use a shared EV because of access to privileged

parking at their destinations.

25

Figure 14. Charging Ports in Westchester County

Data: Charge Point 2017

2.4.3 Public Transit

Westchester County has a robust multimodal transit network. Metro-North’s regional rail network

serves twelve counties with five rail lines, stretching 384 route miles in length. The system is increasingly

popular, breaking its previous ridership record for the fourth consecutive year, providing 87 million rides

in 2017. These rides are concentrated in Westchester, with 84 million (of 86 million) of its 2016 rides on

the Harlem, Hudson, and New Haven lines, which serve 42 stations in the county. While some of these

rides do not originate or terminate in Westchester, they demonstrate the robustness of the transit system

that runs through the county. In addition to Metro-North’s rail service, six Amtrak lines run through

Westchester, connecting the county to the broader region.

The county Bee-Line Bus System serves 100,000 daily weekday riders with nearly sixty bus

routes. The system moved a total of 28.6 million passengers in 2017. Service is primarily in southern

Westchester County, where population density is greatest, with about 65% of Westchester residents

living within a half-mile of a bus line. Fourteen of the Bee-Line’s routes run into the Bronx, facilitating

transfers between the Bee-Line and the MTA subways and buses. An integrated payment system with

the MTA MetroCard facilitates these transfers, allowing riders to switch between services free-of-charge.

26

Although the Bee-Line service saw an overall decline in ridership, its worst-performing routes were a

number of commuter routes and all of its shuttle routes, many of which saw ridership decline by more

than 20% between 2013 and 2016.

Most Bee-Line riders are young, women, low income, and minorities. About 38% of riders are under

the age of thirty and 62% are women. Approximately 49% of rider households in 2016 had incomes

less than $25,000, 83% of whom are African American (45%) or Hispanic (38%). Although ridership

has decreased with the recent economic recovery, seniors have continued to ride, with ridership of those

sixty or older growing from 9% to 12% between 2013 and 2016, matching the growth in the Westchester

senior population.

Bee-Line riders are transit dependent. Only 17% of riders have a driver’s license and a vehicle available

to them; an additional 20% of riders have a valid driver’s license, but no car available. More than half of

riders do not have access to a car or valid driver’s license.

61

According to a survey conducted by the City

of White Plains, 39% of riders departing White Plains Station during the evening-peak period got to the

station by bus. These commuters are more likely to be part-time shift workers with lower incomes than

morning-peak commuters, only 14% of whom said they got to the station by bus.

It is not clear whether the rides lost between 2013 and 2016 were substituted by rail trips, personal

vehicle trips, hailed rides (i.e., taxi, livery, rideshare), another mode, or if Westchester residents are

simply travelling less. A robust economy could have been the reason of why residents starting to choose

other more comfortable methods of transportation. If Westchester residents are travelling less by bus as

a result of the economic recovery, this would suggest that the bus is not a popular mode (bus ridership

across the U.S. has been dropping since 2012).

62

The concentration of residents and jobs in downtowns, and in the three target cities in particular,

reflects access to mobility alternatives in the county. The county Bee-Line bus network primarily

serves the target cities and Mount Vernon. These cities also exhibit the highest density of residents

around Metro-North’s rail stations. As noted in the first section, carshare serves well as a complement

to other mobility alternatives and in combination, these mobility alternatives can encourage a shift away

from the POV. The high density of transit services in the downtowns of target cities makes them

particularly well-adapted to carshare.

27

2.4.4 Taxis and Limousines

Taxis and limousine services are popular in Westchester. As of May 2018, 317 taxi and limousine

companies were licensed to operate in Westchester County, more than a third of which had their

base-stations in Yonkers (68 base-stations), White Plains (23), and New Rochelle (20).

63

For the

most part, these services do not serve as traditional taxis: only 20 of the 317 businesses might be

considered strict taxi services.

64

Based on a survey of company websites, the Westchester

limousine services principally provide chauffeured rides to New York City and airport service.

Despite their limited numbers in Westchester, taxis are popular, and often serve first and last mile

connections to/from rail stations. A survey conducted by the City of White Plains of departing

passengers from the White Plains Station found that around 7% of riders got there by taxi during

the morning-peak period, compared to 8% during the evening-peak period. Further, according to a

report produced by the Planning Division of the Westchester County Department of Public Works

and Transportation, taxi-stands are common in Westchester at rail stations with many riders taking

a taxi home in the evening.

65

2.4.5 Transportation Network Companies

Transportation Network Companies (TNC) are extremely popular, with 78% of Uber users reporting

the service as extremely or very satisfying.

66

TNCs increase personal mobility, especially for difficult

to make trips: almost half of TNC users say they go more places because of the service and 12–22% of

users say they would not have made a particular trip without the service.

67-68

Until June of 2017, TNCs could not operate in New York State except in New York City. Before then,

TNCs operated illegally in Westchester County unless going to or coming from the City. With Governor

Cuomo as its champion, State legislation passed in June 2017 allowing TNCs to operate outside of

NYC if they receive the county’s consent to do so. Following a brief stalemate between Uber and

former Westchester County Executive Robert Astorino regarding safety concerns, Astorino

approved TNCs to operate in Westchester.

28

Little data is publicly available about the trips served by TNCs. However, survey data collected

by researchers at the UC Davis’ Institute of Transportation Studies suggest that riders in major U.S.

metropolitan centers use the service regularly and principally to avoid parking or drinking when driving.

69

This indicates that carshare (and residential carshare) serve different use cases than ride-hailing services.

As such, ride-hailing services and carshare likely act as complementary mobility services rather

than substitutes.

In Westchester, passengers of the Bee-Line bus followed the national trend of declining bus ridership;

this is likely in part because of the growth of TNCs. While Bee-Line ridership between 2013 and

2016 decreased by 10%, ridership on commuter and shuttle routes decreased by 19%. Shuttle routes,

in particular, saw their ridership decrease by 30% in that same period. According to the 2016 Bee-Line

Bus Survey, however, the principal culprit of this declining bus ridership is the continued expansion of

parking facilities at rail stations.

70

Nevertheless, the popularity of taxi-stands in Westchester, noted in

the above section, suggests that TNCs may be serving the same role.

Although LMI people tend to own fewer cars and ride transit more, they are also less likely to use

ride-hailing services: “Respondents with an annual household income of $35,000 or less had an

adoption rate of 15%, as compared with 33% of those earning $150,000 or more.”

71

Other surveys

have found similar results.

72

As such, TNC services may be cost-prohibitive for many of Westchester

LMI residents. A subsidized residential carshare system could help fill this mobility gap. The study

team weighs this possibility in the pro forma (see section 5.8).

2.4.6 Walking and Biking

Most of Westchester County presents a challenging landscape for walkers and bikers. Alhough many

commercial centers in the county are walkable, they can be difficult to access by foot on account

of Westchester’s hilly and sprawling landscape. Irregular sidewalk networks, wide highways, rail

corridors, and commercial arterials further complicate walking and biking in Westchester. Increasingly,

in an effort to appeal to younger generations, Westchester cities are emphasizing pedestrian and bike

infrastructure and transit-oriented development. The target city profiles in section 2.5 describe these

efforts in greater detail.

29

2.4.7 The Potential for Carshare in the Evolving Mobility Landscape

Westchester's mobility landscape is in transition: bus ridership is rapidly declining while Metro-North’s

ridership has hit record highs; TNCs and taxis are popular, ferrying rail-riders to and from stations;

Electric vehicles are increasingly popular; and Westchester municipalities are retrofitting their

downtowns for walkers and bikers (with some introducing new bike-share systems). Nevertheless,

the POV remains the dominant mode of choice for Westchester residents.

New mobility options benefit Westchester County low-income residents, who disproportionately own

fewer POVs than their wealthier counterparts. However, these individuals remain much more likely

to ride traditional public transit and much more likely to access rail stations by foot rather than other

modes. This is in part because low-income individuals are more likely to live in high-density areas

close to transit, although in large part, they are less able to afford POVs and taxi and TNC services.

As noted in the first section, carshare does best in medium and high-density areas where mobility

alternatives to the POV exist. Moreover, carshare benefits LMI individuals in particular. As such,

carshare is well suited to Westchester’s principal municipalities—Yonkers, White Plains, and New

Rochelle—particularly in downtown areas and immediately surroundings. Population density in these

areas is much greater than elsewhere in the county, and the residents are more likely to have low and

medium incomes. The following section explores the potential for carshare in the target municipalities

in greater detail.

2.5 Target City Profiles

2.5.1 New Rochelle

New Rochelle, with a population of 79,557 residents, is the second largest city in Westchester County

and had the greatest growth of the three cities, with 3.2% increase in population from 2010 to 2017.

73

New growth in the past decade represents a reversal in the trend of decline that took place from the

1960s through 1990s. New Rochelle is planning and preparing a resurgence that will bring population

and commercial growth for the city, particularly the downtown area.

30

In December 2015, New Rochelle rezoned 279 acres in its downtown, including most of the city’s

commercial areas, and allowed for taller construction. Now, developers can build up to 40 stories

as-of-right in certain locations, and more than 40 stories in exchange for providing certain community

amenities. New Rochelle signed an exclusive master plan development agreement with RXR Realty

and Renaissance Downtowns (RDRXR), that will lead “the most significant economic development

initiative in the city’s history.”

74

Shortly after the downtown rezoning, New Rochelle adopted The New Rochelle Comprehensive

Master Plan to shape anticipated new development. The Master Plan is framed around two key concepts:

1. Direct high-density downtown development to better support its emergence as a regional

center with critical regional connections.

2. To incorporate the principles of sustainability, as set forth in GreeNR.

The master plan’s dual emphasis on sustainability, combining strategies to reduce emissions with

providing housing opportunities “for seniors, young professionals, families and a growing regional

population,” make it an interesting testing ground for sustainable mobility solutions that meet

changing demographics.

2.5.2 White Plains

White Plains is the smallest of the three cities, both in terms of population (58,241 people) and land

area (nearly ten square miles) and is the least dense (5,961 residents per square mile). It is the county

seat for Westchester and was developed as a commercial hub for the county.

The city is a regional employment center and commuter hub, anchored by its job-dense, transit-friendly

downtown. White Plains is the destination of 54,000 commuters, 91% of which are workers coming from

outside the municipality, and the origin of another 21,000 commuters, most destined for Manhattan. As

such, the White Plains rail station is the third busiest in the Metro-North system, shuttling residents to

Grand Central Terminal in about 45 minutes. To accommodate the large volume of commuters into the

City, the Westchester Bee-Line Bus system runs 28 lines through White Plains, most running East-West

via its centrally located transit center.

White Plains was one of the first suburban cities to develop large-scale retail, which attracted the likes

of Bloomingdales, Macy’s, Nordstrom and other retail giants in the post-World War II era. Urban

renewal in the 1960s brought on a wave auto-oriented mixed-use redevelopment in the downtown, with

31

a cornerstone shopping mall, new commercial and hotel towers, parking garages and lots to

accommodate visitors and commuters, and eventually large corporate office buildings. While

White Plains has fluctuated in size and activity over the decades, the city’s high-density mixed-use

downtown has grown substantially more recently—nearly 30% since 2000.

75

As part of its new Strategic Plan released in 2016, White Plains is undertaking a number of efforts

to improve the mobility alternatives available to its residents. These strategies are divided into

mid-term strategies, those that fall within the three- to five-year horizon, and long-term strategies,

those that require more than five years to coordinate and implement. Notable in the Strategic Plan

are its ambitious environmental goals, including the reduction of the number of VMT by 1,500 miles

per capita in 30 years, or a reduction of 50 miles per person per year. This strategy has a timeline to

monitor its implementation, so that in five years the city expects to reduce 124.92 VMT, in 15 years

the number becomes 606.75VMT, and finally, in 30 years, the goal is to have reduced 1522.86 VMT

per person per year.

76

With these goals in mind, the city is introducing more bike infrastructure, having recently painted lanes