State of the Wine

Industry 2018

Written by Rob McMillan, EVP and Founder

Silicon Valley Bank Wine Division

Contents

Introduction 3

2017 predictions in review 5

2018 wine business predictions and observations 7

Evidence of changing consumer preferences 9

Generational changes and wine demand 22

Direct-to-consumer sales 27

Retail evolution 34

Harvest, bulk wine and land 38

Notes 42

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

2STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

Introduction

The US wine industry is at the tail end of its largest

growth period in history. Since 1994, the industry has

experienced long-term trends of increasing volumes

and higher prices, with only minor attening periods

during recessions (see gure 1).

1

790

MILLION GALLONS

OF WINE CONSUMED

IN THE US IN

2016

3STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 INTRODUCTION | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Today, consumers are leaving the lower price segments in favor

of better-quality oerings, but aer more than 20 years of

straight-line growth trends, total volume growth is leveling out.

Premiumization is still the dominant trend, so volume drops in

lower-priced generics are part of the explanation for attening

volume; but in a more recent development, even premium wine

growth is slowing.

Winery owners, who have seen grape prices escalate markedly

over the past ve years, are nding that cost increases are

dicult to pass on to new consumers, who are signaling that they

have a lower indulgence ceiling than have prior generations.

While the economy overall, as of this writing,

1

is demonstrating

the best results since the 2007–2009 recession, the economic

circumstances that set the stage for the industry’s 20-year

growth trajectory cannot be repeated. The factors that made

you successful to this point will not enable you to sustain

that success. This means the winning sales strategies you are

leveraging in the operating environment today will slowly

prove fallible tomorrow.

Successful wineries 10 years from now will be those that adapted

to a dierent consumer with dierent values — a customer who

uses the internet in increasingly complex and interactive ways,

is frugal and has less discretionary income than their predeces-

sors. Successful companies will be those that evolve retail

strategies away from the winery location as the sole point of

experience and nd other, scalable means of delivering the

experience — and the wine — to consumers where they live.

Figure 1: US wine consumption

Volume

800

750

700

650

600

550

500

450

400

350

300

Millions of gallons

Sources: California Wine Institute, Gomberg-Fredrikson, BW166

1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016

Successful wineries

10 years from now will be those

that adapted to a dierent

consumer with dierent values

INTRODUCTION 4STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 INTRODUCTION | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

2017 predictions

in review

We have been researching the wine business since 1991 and

making predictions for more than a decade. Some years, we

properly characterize a market change; in other years, our

ndings might be o in timing or even wrong,

2

but we always

review the forecasts made the prior year just to keep score.

In 2018, a key prediction we will miss in sales growth sets

up a broader discussion of market changes.

2

5STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 2017 PREDICTIONS IN REVIEW | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

What we got right

• We were correct when we suggested that labor shortages,

which were an understated part of the conversation in 2017,

would escalate throughout the year.

• We predicted that M&A activity would remain very high in

2017, and it did, capped by the 600-acre Stagecoach Vineyard

purchase by E. & J. Gallo.

3

• We said that import growth in lower premium price points

would increase. France, Italy and New Zealand all have

accelerated their wine sales in the US and are gaining market

share from domestic wineries.

• With respect to segments, we correctly predicted the

following:

› Under $9 bottled wines would continue to struggle.

Price drops for glass format wines were to be expected.

› Wines sold between $12 and $25 would grow in demand,

and limited price increases would be available. Price

increases were quite limited, but demand in the segment

did grow.

› Wines sold between $35 and $75 would nd price

increases dicult without the US economy’s demonstrating

improved performance.

› High-end luxury wines with an established brand would have

no problem retaining volume levels and making small price

increases.

• With respect to land, we were correct to predict the following:

› The narrowing supply of arable land suitable for higher-end

wine production combined with good buyer interest would

drive vineyard prices higher in premium regions.

› Vineyards in Oregon and Washington would continue to

see high interest from larger wine companies.

› California’s Central Valley would have some additional

acreage to remove.

• Per capita consumption (case volume divided by population

growth) would face headwinds in 2017, but if economic

conditions continued to improve, those impediments would

be oset, leading to slightly higher per capita consumption

for another year.

• The presence of millennials would be most visible in the

$8 to $12 red blend category, but they would gradually move

away from blends and into varietal wines or imports as their

incomes improved. We saw growth in chardonnay and lower-

priced imports in 2017.

• Restaurant wine sales would show limited to zero growth in

2017, which is an improvement over recent negative-growth

years. Restaurant sales did have limited overall growth, but

the industry continues to struggle with closings, declining

same-store sales and outdated store concepts.

What we got wrong

We predicted a sales growth range for the premium wine

segment of 10 to 14 percent in 2017, up from 9 to 13 percent in

2016, describing the conuence of good supply, strong consumer

demand and better retail conditions as factors in delivering

improved industry performance. We also said that industry

growth would be 2 to 3 percent in volume and 4 to 6 percent

in dollars.

From all the sources we can nd today, we see growth ranges in

wine consumption dropping over our expectations at the start of

2017. That is not to be confused with lower sales. Sales are still

increasing, but growth rates are slowing.

Our own database of winery nancial statements shows that

sales growth through the nine months ended September 2017 is

0.3 percent, vs. 9.8 percent for the same period in 2016. For the

industry overall, we are showing 0.6 percent growth in volume

and 2.4 percent growth in dollars, using Nielsen data,

4

so again

we were high on both estimates.

While we still have the October-November-December data to

potentially improve 2017 results, it looks as though we will

miss our sales forecast for the rst time when the nal year-end

numbers are tabulated. We can lick our wounds a little because

we were correct in saying that all the growth would be in the

above $9 segment, but that’s little comfort.

PREDICTIONS IN REVIEW 6STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 2017 PREDICTIONS IN REVIEW | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

WINE BUSINESS PREDICTIONS AND OBSERVATIONS

2018 wine business

predictions and

observations

3

7STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 2018 WINE BUSINESS PREDICTIONS AND OBSERVATIONS | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Industry

• We predict a sales growth range of 4 to 8 percent for the

premium wine segment, down from the 2017 sales growth

estimate of 10 to 14 percent. For the industry as whole,

sales will rise by 2 to 4 percent, while volumes will increase

up to 1 percent.

• We expect acquisitions to cool somewhat from the torrid

pace of the past three years as many of the major buyers

digest their recent purchases. We will still see foreign

purchases of US wineries and signicant transactions for

vineyard properties over the next 12 months.

• Increasing imports will continue in the lower premium

price points.

Supply

• By all accounts, when 2018 totals are calculated California

will have crushed about 3.8 million tons of grapes, slightly

more than in 2017. Pacic Northwest harvests will set another

record in terms of yield in Oregon and will moderate slightly

in Washington.

• Overall supply is balanced, with chardonnay demonstrating

particularly strong demand. Cabernet is balanced with at to

down pressure at the high end of the market.

• California vineyard prices in premium regions will atten

compared with the strong growth we’ve seen for the past

ve years.

• Oregon and Washington vineyards will continue to see high

interest from larger wine companies with increasing pricing.

• The California Central Valley is closer to being in balance

aer 2017 acreage removals, but some additional removals

will be needed in the southern San Joaquin Valley to produce

sustainable pricing opportunities.

Demand

• Retiring baby boomers and frugal millennials drive a rotation

of consumer preferences. Premiumization will continue,

but soening is likely on the luxury end for wineries without

strong brands. For established brands, growth opportunities

remain positive.

• Millennials are migrating away from red blends and intro-

ductory wines and are starting to have a positive impact

on lower-priced still wine categories — both domestic and

foreign. This trend will continue.

• The Gen X cohort will surpass the baby boomers around 2021

to become the largest ne wine consumer demographic in the

US. By 2026, millennials will surpass Gen Xers to become the

largest ne wine–consuming cohort.

Price

• Price increases will be dicult to pass through in 2018.

Overall pricing should be at.

• Routinely increasing both volume and price, as has occurred

over the past 20 years, will prove dicult for wineries given

the low-growth, low-ination environment.

WINE BUSINESS PREDICTIONS AND OBSERVATIONS 8STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 2018 WINE BUSINESS PREDICTIONS AND OBSERVATIONS | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Evidence of changing

consumer preferences

Luxury goods

Premium wine is a luxury product. It sells in dierent ways than do

luxury automobiles, leather and eyeglasses, but there are insights

to glean from the behavior of the luxury market — the channels in

which it operates, how products are sold and how they are marketed.

4

9STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

According to the newly released annual Bain Luxury Study,

5

the

large American market (including both North and South America)

has been undergoing wrenching changes in consumer preference

and retail strategies. The American market was expected to

report at growth for 2017 but instead managed to nish the

year in positive territory, growing by 2 percent. This is compared

with other developed luxury markets — which show much better

growth opportunities — led by China, which boosted sales by

15 percent.

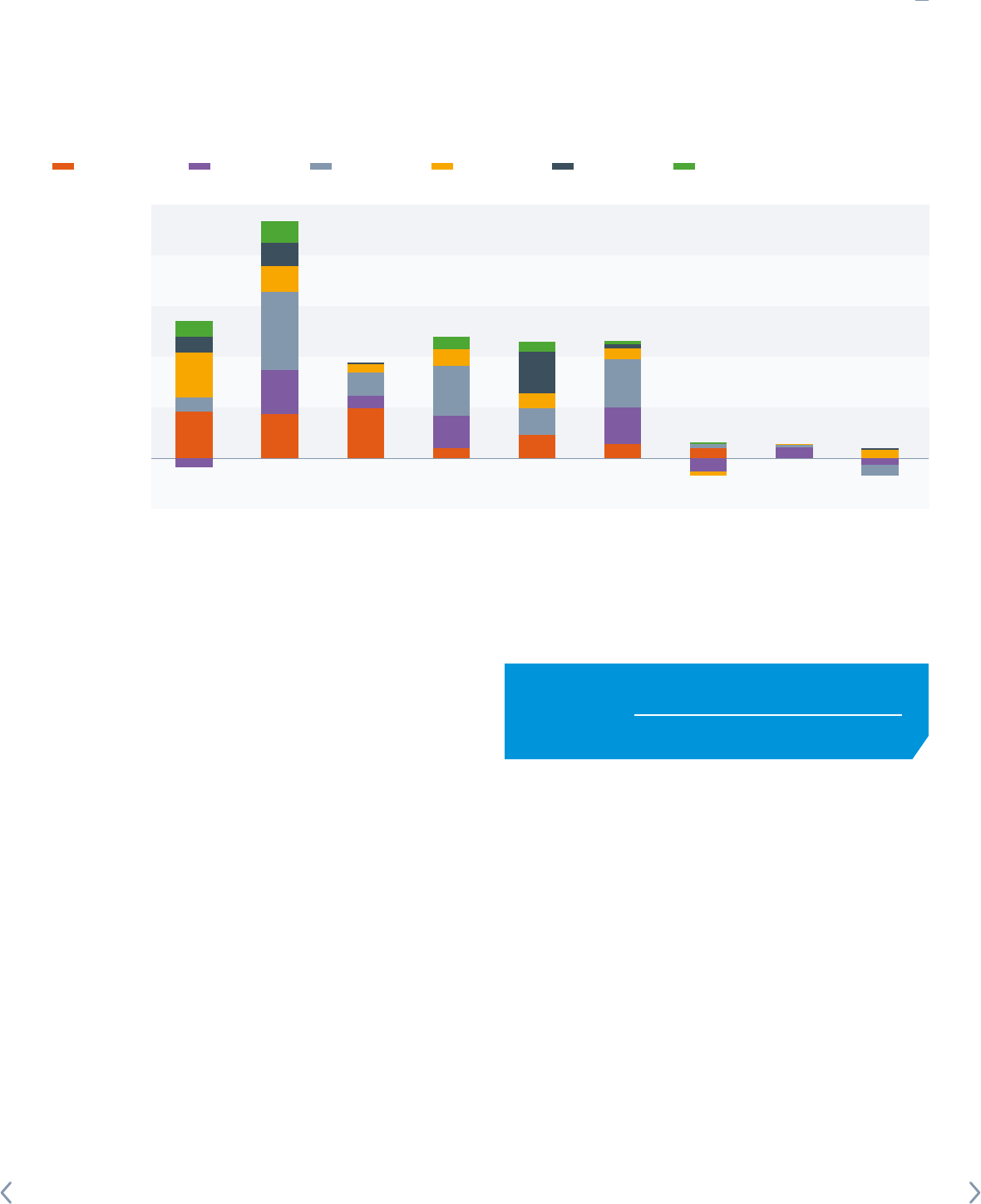

For the US specically, growth following the market collapse

was robust, exceeding 10 percent in all categories except

eyewear, with the growth rate in luxury wine and spirits nearing

15 percent. But since 2011 the growth rate in luxury sales has

trended down to the current rate of 2 percent. Fine wines,

champagne and spirits are a near proxy for the sector’s growth

change (see gure 2). Why is growth slowing in the US but

advancing in other parts of the world?

The face of the US consumer is changing, as are the paths to

market. Bain estimates that online selling, which at one point

was thought of as an anathema to the luxury experience entirely,

is now an accepted channel and is expected to represent up to

25 percent of total sales by 2025. Retailers are now struggling to

dene their digital experience away from sales by location, and

that is proving dicult, particularly for the mono-brand stores.

The consumer too is evolving. While single-brand stores

are struggling, o-market stores and airport shopping are

thriving. The US consumer, whether young or old, is focused

on experience and value, and that is forcing change in retail

marketing strategy. No longer can the store experience be the

dening characteristic for the luxury buyer; in that fact is a

warning for wineries that depend on the tasting room as their

only path to direct sales.

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

–5%

–10%

–15%

–20%

–25%

Source: Euromonitor International Passport, December 2017

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Designer apparel and footwear (ready-to-wear)

Luxury eyewear

Luxury leather goods

Figure 2: Sales growth rate of US luxury goods

Luxury writing instruments and stationery

Fine wines/champagne and spirits

Luxury jewelry

Luxury timepieces

Superpremium beauty and personal care

Percentage of sales growth

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES 10STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Premiumization: Below $9 retail wine

Over the past decade, the moniker that has stuck to describe

consumers’ willingness to pay more for wine has been

“premiumization.” Besides butchering the English language,

it’s not really an apt term because, as any winery owner will

tell you, while consumers are trading up on average, it’s still

very dicult to increase prices. So how are consumers trading

up if prices aren’t rising?

The truth is, while the consumer has been willing over the past

decade to spend more on average, the trade-up has more to

do with a decline in demand for lower-priced value wines vs. a

willingness by all consumers to spend more on a given bottle

(see gure 3).

The break point between growth and decline in sales falls at

around $9, and in 2017 the segment below $9 declined in both

dollars and case volume. The only countervailing dynamic of

the trend has been a short-lived improvement in $3 to $6 wines,

but even that miniscule bright spot is not what it seems. It really

is reective of larger-format box wine.

$60,000,000

$40,000,000

$20,000,000

$0

–$20,000,000

–$40,000,000

–$60,000,000

–$80,000,000

–$100,000,000

Sources: Nielsen Beverage Group, SVB Analysis 2

1/2015

2/2015

3/2015

4/2015

5/2015

6/2015

7/2015

8/2015

9/2015

10/2015

11/2015

12/2015

1/2016

2/2016

3/2016

4/2016

5/2016

6/2016

7/2016

8/2016

9/2016

10/2016

11/2016

12/2016

1/2017

2/2017

3/2017

4/2017

5/2017

6/2017

7/2017

8/2017

9/2017

10/2017

Figure 3: Rolling 52-week sales growth of wine below $9

$0–$2.99 $3–$5.99 $6–$8.99

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES 11STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

The volume and growth came in $3 to $6 wines because all the

formats are converted to 750-milliliter bottles, and $14+ box

wine is a growth segment. The box wine category has been

largely dominated by Constellation Brands and Delicato Family

Vineyards, but Trinchero Family Estates, E. & J. Gallo Winery

and The Wine Group also participated, each using its distribution

muscle to push larger box and Tetra Pak formats (see gure 4).

So even the minor positive news in the below $9 segment is a bit

of a mirage because better juice is being sold more eciently

in larger containers. It does demonstrate how consumers remain

value conscious.

Because the $3 to $6 price segment represents such a large

component of volume sales — 45 percent — it was noteworthy

to see the growth, but it should not be viewed as a reversal of

the premiumization trend.

Premiumization: Above $9 retail wine

While there is no real denition of the term “premium wine,”

we dene it as wine above $10 per bottle. That segment

dominates sales and is responsible for all the growth in the

trade today (see gure 5).

$300,000,000

$250,000,000

$200,000,000

$150,000,000

$100,000,000

$50,000,000

$0

Sources: Nielsen Beverage Group, SVB Analysis 4

Figure 5: Rolling 52-week sales growth of wine above $9

Figure 4: Top-growth box brands

52 weeks

Sources: Nielsen Beverage Group, SVB Analysis 3

Company Top-growth box brands Total category tracked sales Total category tracked growth Brand growth rate

Constellation Brands Vendage, Black Box $256,533,915 $57,351,551 28.8%

Delicato Family Vineyards Bota Box, Cellar Box $201,189,114 $41,740,002 26.2%

Trinchero Family Estates Sutter Home $19,466,059 $391,683 2.1%

E. & J. Gallo Winery Peter Vella, Liberty Creek, Naked Grape $153,718,861 –$835,355 –0.5%

The Wine Group Franzia $473,322,778 –$12,342,791 –2.5%

1/2015

2/2015

3/2015

4/2015

5/2015

6/2015

7/2015

8/2015

9/2015

10/2015

11/2015

12/2015

1/2016

2/2016

3/2016

4/2016

5/2016

6/2016

7/2016

8/2016

9/2016

10/2016

11/2016

12/2016

1/2017

2/2017

3/2017

4/2017

5/2017

6/2017

7/2017

8/2017

9/2017

10/2017

$9–$11.99 $12–$14.99 $15–$19.99 ≥ $20

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES

12STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Looking back, the only time in recent memory that we have

seen trading down as a trend was during the Great Recession of

2007–2012, but in reection things weren’t what they seemed.

During that nancial crisis, wine conference discussions

centered around the direction of spend, and trading down was

discussed as a consumer trend. There was supply chain and

demand disruption, but consumers who were hurt by the

nancial collapse did not give up their wine; they just switched

to less expensive options, but it wasn’t trading down in terms

of consumer preference. In a market-driven paradox,

many of those less expensive wines sold during the

recession were actually the more expensive ne wines

from producers who had to blend down or discount

wine to move product. It didn’t give lower-cost

producers a true advantage, so an argument can be

made that the consumer has not traded down in the

past 50 years.

Even if we acknowledge the single trading-down data

point during the recession as being valid, there is no

way to create a business from it. A model based on the

hope of recession is clearly misguided. As we oen

say, “Hope is not a strategy.” But the question worth answering

is: Can premiumization (trading up) continue unabated forever?

Slowing premium sales trends

Which current market conditions might be signaling a change to

premiumization? Impaired restaurant sales might be one, but we

see that more as a channel and consumer preference shi. Value-

conscience consumers aren’t eating out as oen or spending as

much on alcohol when they do go out, but they are drinking more

at home.

One possible clue that premiumization is beginning to break

down somewhat is shown in gure 5: While there remains growth

in wines above $9, since the end of 2015 that growth rate has

been declining. That’s a newsworthy change in market direction,

but is it real?

The rst thing we do when we see surprising, contradictory

or confusing data is to consider bias and question the context.

It is possible to draw bad conclusions from good research.

Nielsen data are biased in favor of wine sold wholesale. The data

exclude some nontraditional channel information like Costco,

direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales and some private labels like Aldi

and Lidl that don’t participate in syndicated data collection.

It is possible that the decline is not a decline at all but rather a

channel shi that Nielsen doesn’t pick up in its stats.

Costco is the largest US wine retailer, with close to $2 billion

in wine sales annually, and its wine programs are growing.

DTC sales would also oset Nielsen trends, as there is nearly

$3 billion in direct sales, and purchases are clearly growing

there.

6

No matter what, we always have a hard time dismissing

obvious trends from robust data collectors like Nielsen, so

we need to dig a bit deeper.

Can premiumization

(trading up) continue

unabated forever?

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES 13STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Winery shipments

Gomberg-Fredrikson shipment data from wine warehouses come

at sales trends from a dierent perspective and reect sales from

the winery vs. the retailer (see gure 6).

Through September 2017, wine shipments from warehouses

slowed beginning in August 2015, roughly equivalent to

what Nielsen shows in its time line in gure 5. The Gomberg-

Fredrikson data in gure 6 do include DTC and Costco

shipments, whereas the Nielsen data do not.

Winery nancial performance

Silicon Valley Bank collects nancial statements from clients

and non-clients as part of our daily routine. We then provide our

clients with gratis consulting and benchmarking, and with that

information we can track larger-scale industry moves, as well.

Our database reects the wine industry overall and includes

hundreds of wineries, overwhelmingly from the US West Coast.

Average case production in the database is 27,886, with a range

of 1,000 to 730,000 cases. The average retail bottle price is

about $28.

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

–10%

–20%

Sources: Gomberg-Fredrikson, BW166

Figure 6: Warehouse shipment trends

30,000,000

25,000,000

20,000,000

15,000,000

10,000,000

5,000,000

9-liter cases

1/2013

3/2013

5/2013

7/2013

9/2013

11/2013

1/2014

3/2014

5/2014

7/2014

9/2014

11/2014

1/2015

3/2015

5/2015

7/2015

9/2015

11/2015

1/2016

3/2016

5/2016

7/2016

9/2016

11/2016

1/2017

3/2017

5/2017

7/2017

9/2017

Monthly percent change

Percentage of total California volume Past 12 months cases

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES

14STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

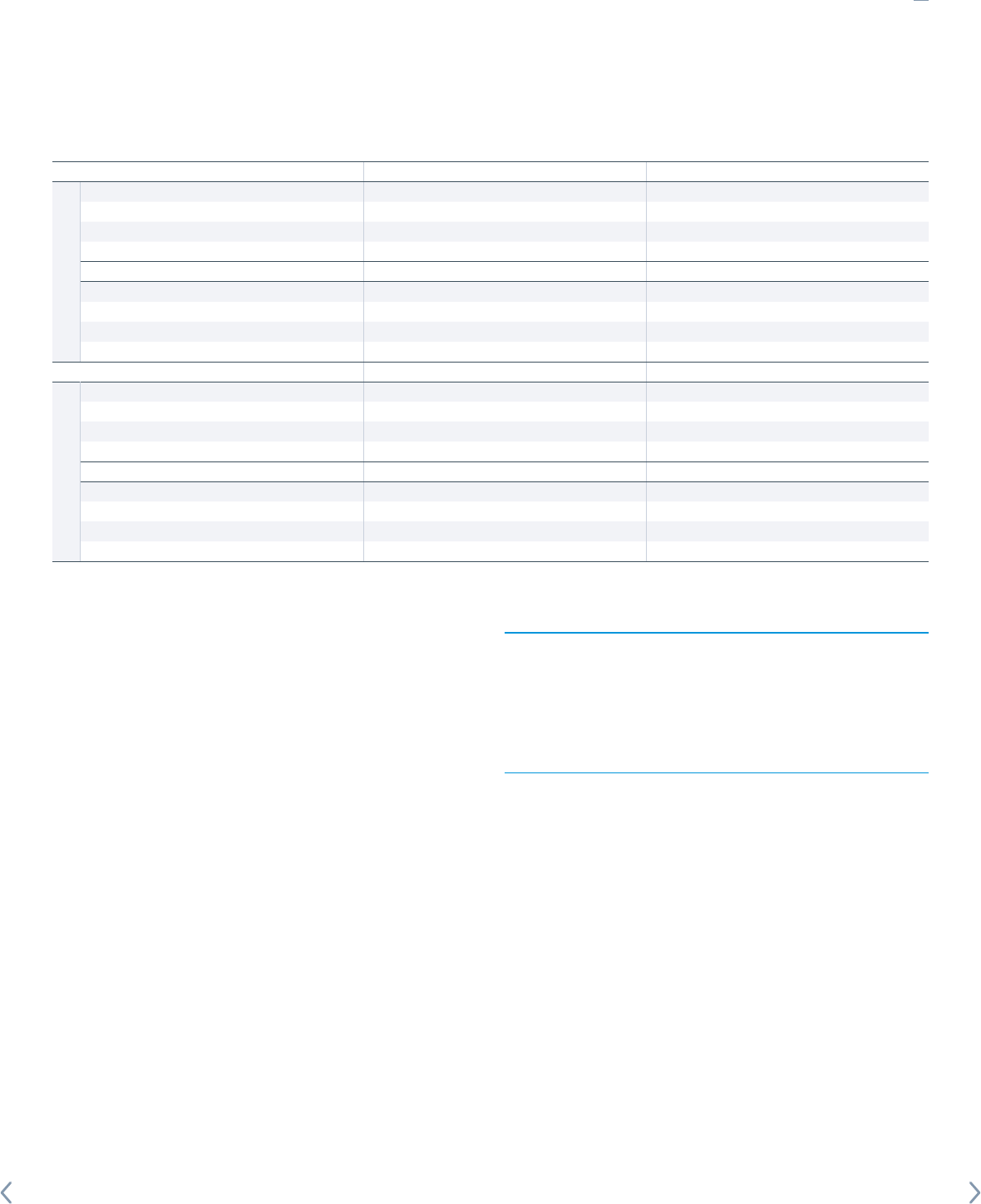

Figure 7 is a product of that database, starting in 2008

when the nancial crisis was in full swing. Note that in

2009, sales growth for the

industry was –3.8 percent and

that it rebounded thereaer.

The trended growth rate has

slowed over the past decade,

while wineries simultaneously

evolved their strategies to direct

models, which should imply

higher average sales prices and

gross margins. Gross margin has trended higher as expected, and

while pretax prot remains between 8 and 12 percent, the latest

period of sales growth in the gure is another point of concern.

Through the nine months ended September 2017, average

sales growth has been a paltry 0.3 percent. That’s less than

a 1 percent growth rate. The only close comparison is the

recession-impacted period in 2009. Although the nine-month

information is missing the heavy October-November-December

period and undoubtedly year-end sales will improve, in 2016

the sales growth rate for the comparable nine-month period was

9.8 percent, so it’s unlikely we will see sales growth improve

before year-end to the 8 to 12 percent we’ve become used to over

the past seven years.

Any of the information in isolation is not concerning, but we

are noting declines in volume growth starting in 2014 from

Wine Institute information (gure 1), shipment declines from

warehouses starting in August 2015, restaurant sales declines

for an extended period now and sales growth declines from

interim winery nancial statements in 2017.

While overall volume in dollars and cases is still growing, the

growth rate for wine overall and even for premium wine started

to slow in late 2015 by most available measures, which implies

that there are underlying changes in demand. Understanding

those trends is key to developing future strategies.

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

–10%

Sales growth and pretax prot

Source: SVB Peer Group Analysis Database

Figure 7: Premium wineries’ nancial benchmarks

12/2008

55.3%

2.0%

9.5%

12/2009

52.4%

–3.8%

2.2%

12/2010

53.7%

10.8%

6.7%

12/2011

53.2%

12.2%

6.1%

12/2012

53.4%

7.7%

6.9%

12/2013

54.8%

9.2%

6.6%

12/2014

56.8%

11.9%

8.0%

12/2015

56.9%

8.8%

9.6%

12/2016

57.4%

9.6%

10.2%

9/2016

57.5%

9.8%

11.6%

9/2017

56.7%

0.3%

9.7%

57%

55%

53%

51%

49%

47%

45%

Gross margin

Gross margin

The growth rate for wine overall and even for premium wine

started to slow in late 2015 by most available measures,

which implies that there are underlying changes in demand

Gross margin

Sales growth

Pretax prot

Sales growth Pretax prot

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES 15STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Imports

Most US ne wine producers have been oblivious of the growth

trends of imports over the past 20 years. Bulk imports have

a more volatile trend but are currently on the rise, and bottled

wine imports continue to grow to record levels (see gure 8).

It’s hard to blame domestic producers for ignoring the inter-

national interloper. When you have the best worldwide market

to sell wine and you can sell all you make, increase your prices

and still grow your volume, why worry?

There has always been enough US consumer demand to feed

imports and domestic production alike, but the future holds

dierent conditions for domestic wineries compared with the

past two decades. Routinely increasing both volume and

price going forward will prove dicult for wineries given a

low-growth, low-ination environment.

As domestic wineries see growth opportunities tapering, they

will start taking notice of the good-value imported wines that are

hitting domestic shores and eroding their market share. When

that day comes, the ght will inevitably become a competition

over the young customer for value. Younger consumers come to

the table with shaper pencils, always looking for the best deal,

and are more open to a world view. Pushing back that tide a year

from now will prove dicult.

Today, the larger producers are ahead of the curve (see gure 9).

Given the high prices being paid for arable vineyard property in

established appellations that drive bottle prices, they are hedging

their bets by buying foreign brands or nding ways to partner

with foreign producers, handing them the precious keys to the

distribution network they seek.

Figure 9: Bottled imports’ price growth

Sources: Nielsen Beverage Group, SVB Analysis 8

Year ended

10/7/2017

Year-over-year

dollar growth

Year-over-year

case growth

French 15.2% 13.4%

New Zealand 10.7% 9.7%

Italian 2.4% 1.4%

Australian –2.0% –2.1%

Spanish –3.4% –2.9%

Argentine –5.0% –5.7%

Chilean –5.9% –3.9%

40%

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

Sources: Gomberg-Fredrikson, Nielsen, SVB analysis

Figure 8: Imports’ share of the US market

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Trend line Import market share

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES 16STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Imports are a threat, and if domestic wine starts losing value

in the consumer’s mind, the big wine companies have foreign

supply to bring into the equation, which will add further pressure

on the smaller ne wine producers.

Reacting to the same set of market circumstances and clamoring

for access to US consumers, foreign wine companies are also

looking for the best way to pursue the US market. Dozens of

European buyers today are waiting in the wings to purchase

domestic wine companies or to establish their own domestic

sales companies in the US and gain a foothold in the world’s

largest consumer wine market. They believe that owning assets

in America will improve their access.

Bottled wine imports continue to hit record levels, driven by

French rosé and sparkling wine, Italian pinot grigio and New

Zealand sauvignon blanc. Australian buyers are importing a large

amount of bulk wine but are seeing declines in bottle sales, as

they are focused on lower-price-point wines that are out of favor.

Restaurant wine sales

On a dollar basis, restaurant wine sales improved in 2017 over

2016, with total US restaurant wine sales up about 2 percent

in dollars but down slightly in volume (see gure 10). Over the

longer term, growth rates continue to slow. Those same trends

of at volumes and higher dollars in restaurant sales are also

reected in retail alcoholic beverage sales overall, so the trend

of lower volume and better dollar sales is no surprise.

In our survey work with wineries, we ask them to tell us the

percentage of their sales that ow through each of the major

routes, such as club, wholesale, DTC and restaurant. With

that information, we can track relative movement in sales to

restaurants from year to year (gure 10).

What is obvious is that wineries are depending less on sales

to restaurants each year, and the larger wineries are more

successful than the smaller ones in selling to restaurants.

2014 2015 2016 2017 (estimated)

Figure 10: Sales to restaurants by producer size

Source: 2016 SVB Direct-to-Consumer Survey

45%

40%

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

Wineries are depending

less on sales to

restaurants each year

1–2,499 2,500–

4,999

5,000–

9,999

10,000–

24,999

25,000–

49,999

50,000–

99,999

100,000–

249,999

≥ 250,000 Average

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES

17STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

For the smaller winery, sales of wine to restaurants has been

declining in importance for nearly a decade, though the decline

has bottomed out of late (see gure 11). At the same time,

restaurants themselves have been suering from mixed same-

store sales and declining bar tabs — both of which are a major

concern of restaurateurs, as alcohol sales have traditionally

been a signicant source of prot. Because of the pressures

on restaurants, which extend beyond this short list, the raw

numbers of US restaurants have been declining (see gure 12).

Explaining this sales trend within the on-premise trade is

complex. The factors shaping restaurant sales of wine today are

a mix of events, starting with traditional three-tier

7

movement

away from smaller wineries. It is magnied by a consumer

movement away from many of the full-service chain restaurants,

the growth in fast casual dining that doesn’t feature wine,

increasing at-home wine consumption and declines in overall

same-store visits. All of that is against the countervailing

backdrop of an improving consumer economy in 2017, leading

to higher average checks. It appears, however, that a better

economy alone is not sucient to fully oset the headwinds.

Big restaurant chains are served by big wholesalers, who in turn

get their wine from big wineries. Every day, restaurant lists are

increasingly being held captive by large producers with access to

distribution, but permanent changes with consumer behavior are

taking place that play into the results, as well.

Our frugal younger consumers don’t want to pay restaurant wine

markups, and retiring boomers are slowing both their spending

and their alcohol consumption volume. Young consumers

know they can buy a bottle of wine at a store for less, so in the

restaurant they are more likely to start with a cra beer or a

cocktail and have a glass of wine with dinner.

8

A more recent

observation is that as millennials are entering their thirties and

nding a career foothold, they are opting out of restaurants in

favor of at-home meals.

9

Figure 11: Small-winery sales to restaurants

Source: 2016 SVB Direct-to-Consumer Survey

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

2014 2015 2016 2017

(estimated)

Figure 12: Number of restaurants in the US

640,000

635,000

630,000

625,000

620,000

615,000

610,000

605,000

600,000

595,000

Sources: NPD Group, Statista.com

Fall

2011

Spring

2012

Fall

2012

Spring

2013

Fall

2013

Spring

2014

Fall

2014

Spring

2015

Fall

2015

Spring

2016

Fall

2016

Percentage of average winery’s sales

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES

31%

19%

16%

17%

18STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

There is good news for the ne wine business: While full-service

chains are struggling with dated restaurant concepts, the small,

independent, local white-tablecloth restaurants continue to

see modest growth, and those are the venues where smaller

producers are more likely to compete for space on the wine lists.

The value equation

“Value” is dened as quality divided by price, and value is the

dominant component for consumer purchasing decisions. When

it comes to ne wine, it’s really quality plus experience divided

by price that denes value, where “experience” is a placeholder

for a shopping experience or the way owning or consuming the

product makes you feel about yourself. But there is no question

that customers buy everything with value in mind, and for that

reason understanding the evolving industry trends in price

segments and varietals is important.

Knowing what consumers are drinking is a key in planning and

planting — and another key to unlocking real drivers of industry

growth. Reviewing emerging trends reveals clues that can be

critical when examining strategies, not only for the big wineries

but also for the smaller family-run ones.

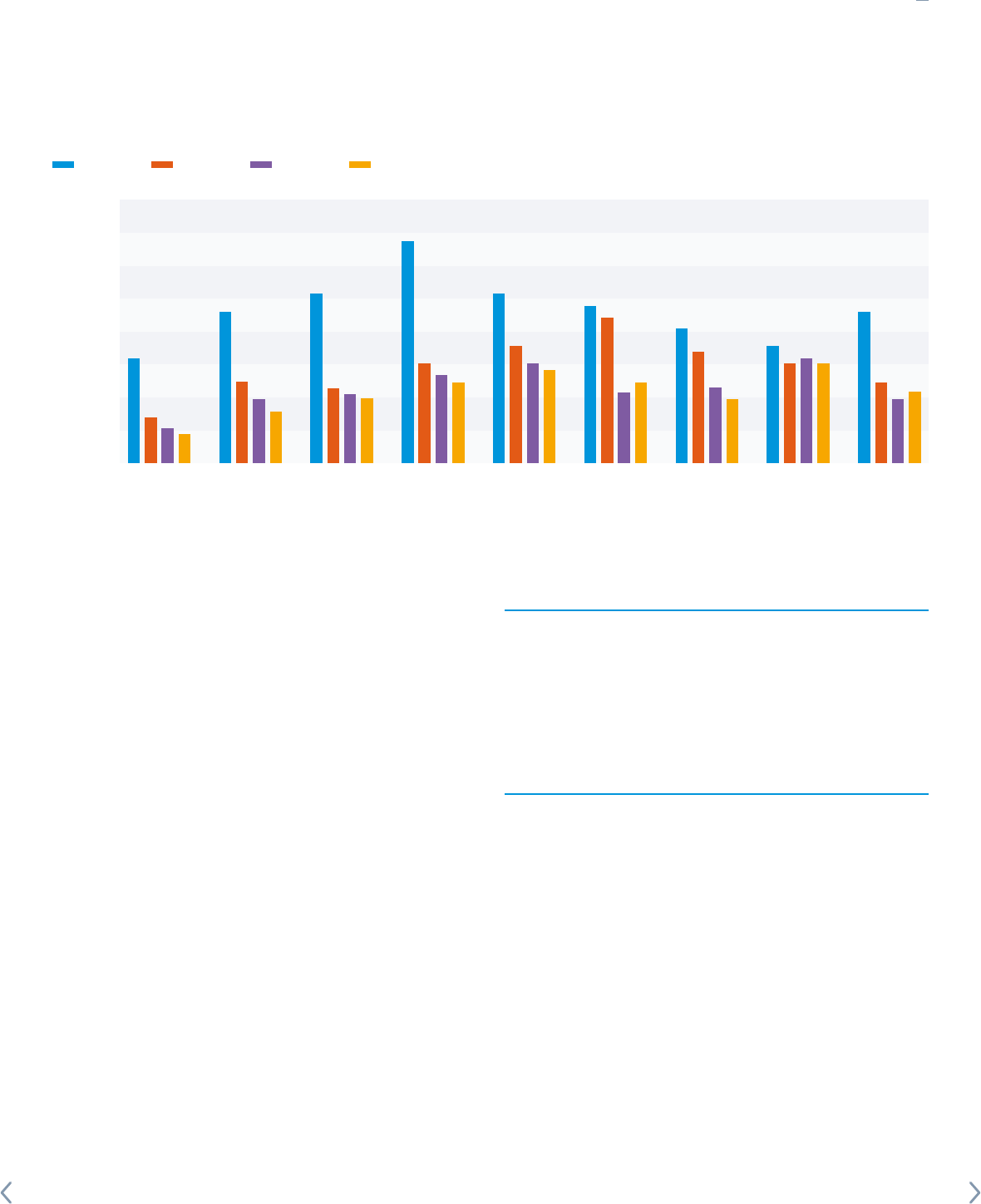

Varietal segment growth

With respect to price segments, reds are still dominating

premium wine growth. Cabernet, red blends and pinot noir are

three of the top four growth varietals (see gure 13). The $11 to

$15 price point is the strongest US consumer growth segment

today, with premium box wine close behind as its own category.

This year the growth trends are showing a couple of surprises.

Figure 13: Growth in varietals

Source: IRI

$100,000,000

$80,000,000

$60,000,000

$40,000,000

$20,000,000

$0

–$20,000,000

Chardonnay Cabernet

sauvignon

Pinot grigio Red blends Pinot noir Sauvignon

blanc

Merlot Moscato Zinfandel

$8–$10.99 $11–$14.99 $15–$19.99 $20–$24.99 ≥ $25

Box wine < $14

value =

quality + experience

price

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES 19STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

While cabernet is still the king of varietal growth overall, and

strongest in the $11 to $15 price range, chardonnay comes

in second this year, replacing the red blend category, which

dropped to third place. Sauvignon blanc, pinot noir and pinot

grigio rounded out the top growth varietals (see gure 14).

Red blends, though cooling o slightly, are a dream from the

large producer’s perspective. The category allows the large wine

companies, which dominate production, enormous freedom in

the substitution of varietal and place of origin, yet they are still

able to maintain overall quality and margin. There may be wide

bottle-to-bottle variation in a given SKU,

10

but for the price the

quality is generally there for the current entrants. This is no

longer just a sub-$20 product, however; note the success of the

top four red blend brands above $20 in gure 14.

From the consumer perspective, red blends are really the jug

wine craze of the 1960s on steroids. Like the mature generation

who cut their teeth on generics, emerging consumers are

acquiescing to the branding of the large wine companies because

wine is a complex consumer good and branding makes their

purchase easier. It replaces varietal and vintage comparisons

with something simple and catchy like Sexy Wine Bomb, The

Prisoner, Vicious Red Blend, SLO Down Sexual Chocolate, or

Cupcake Red Velvet.

11

If consistency is maintained in these red

blends targeting the emerging wine consumer, brand loyalty will

be there until the customer seeks more-distinctive wine. At that

point, the red blend will fade just like Lancers, Mateus

12

and Blue

Nun

13

did for the boomer and mature generations before them.

The inexpensive red blend category might today be seeing the

beginning of the end of the fad.

Packaging is playing a role in consumer demand, as well.

The 3-liter premium box wine and Tetra Pak formats continue

to grow, with cabernet, chardonnay and pinot grigio each

individually responsible for more than 20 percent of varietal

growth. Canned wine continues to garner press because it’s

growing by 66 percent o a small base, but it’s a tiny sector,

representing less than 1 percent of total wine sales, and is

unlikely to truly gain anything but a footnote in sales results.

Cabernet Average price Chardonnay Average price Red blends Average price

All brands

Josh Cellars $12.57 Butter $14.75 Apothic Wines $9.42

Robert Mondavi Winery $12.42 Josh Cellars $11.37 Roscato $10.88

Black Box Wines $18.86 Black Box Wines $18.86 19 Crimes $9.68

Caymus Vineyards $76.98 Ménage à Trois Wines $9.16 Stella Rosa Wines $11.84

Sauvignon blanc Pinot noir Pinot grigio

Kim Crawford Wines $13.96 Meiomi Wines $19.11 Bota Box $18.31

Whitehaven $15.59 Black Box Wines $19.13 Black Box Wines $19.06

Prophecy Wines $10.43 Prophecy Wines $10.14 Prophecy Wines $10.58

Oyster Bay Wines $11.41 Line 39 $9.14 Liberty Creek Vineyards $7.08

Cabernet Chardonnay Red blends

Brands > $20

Caymus Vineyards $76.98 Rombauer Vineyards $34.19 Cooper & Thief Cellarmasters $24.96

Jordan Vineyard & Winery $52.79 Sonoma-Cutrer Vineyards $21.87 Conundrum Wines $21.85

Justin Vineyards and Winery $23.33 Frank Family Vineyards $30.26 The Prisoner Wine Company $41.05

Intrinsic Wine Co. $20.25 Mer Soleil Vineyards $27.54 Pessimist $20.15

Sauvignon blanc Pinot noir Pinot grigio

Duckhorn Vineyards $26.35 Decoy Wines $20.19 Santa Margherita $20.63

Cloudy Bay $28.51 J Vineyards & Winery $20.55 Livio Felluga $24.17

Cakebread Cellars $31.86 Flowers Vineyards & Winery $46.15 Jermann $24.51

Frog’s Leap Winery $22.33 Belle Glos $50.12 Cantina Terlano-Kellerei $24.06

Figure 14: Top-growing brands sold in the US

Source: Nielsen Beverage Group

The inexpensive red blend

category might today be seeing the

beginning of the end of the fad

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES 20STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Consumer preference

Who is driving the growth in these categories? Our own research

suggests that the two growth cohorts are millennials and Gen

Xers. The retiring baby boomers, however, are starting to have

an impact on growing lower premium price segments and are

edging back from the higher-price segments they previously

dominated (see gure 15). You can see the evolution of their

preference curve, which is starting to form a V shape, demon-

strating that boomers are still a power in luxury wines but are

aecting lower-priced wine too.

There is no question that we are seeing a changing of the guard

in premium wine. Young consumers are giving blends a chance,

and from our view their palate maturation looks like a sequel to

the baby boomers’ entrance to wine, which started with Bartles

& Jaymes

14

and then moved to white zinfandel and chardonnay

before settling on merlot. It is interesting to note that the No. 2

growth varietal under cabernet this year is chardonnay, which

is a natural place for palate-expanding millennials to move aer

sweet red blends.

What happens when more of the matures leave the consuming

market and the baby boomers move down the premium price

ladder and collide with millennials, who also want wines that

are more distinctive and consistent and that have a greater

sense of place than a red blend? Where does the consumer push

the growth curve next? My bet is Oregon pinot noir, $15 to $25

limited-production domestics and premium foreign wines.

Figure 15: Generation share of wine consumption by bottle price

2017

Source: Estimated from 2016 SVB Annual Wine Conditions Survey data

Millennials (age 22–38)

50%

45%

40%

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

< $15 $15–$19.99 $20–$29.99 $30–$39.99 $40–$69.99 ≥ $70

Gen Xers (age 39–50) Boomers (age 51–68) Matures (age 69+)

Where does the

consumer push the

growth curve next?

EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES 21STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 EVIDENCE OF CHANGING CONSUMER PREFERENCES | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Generational changes

and wine demand

Today, we see the impact of four generations in the US wine trade,

with Generation Z on the doorstep. The consumer behavior and demand

from each is evolving the industry in obvious ways. At the same time,

the consolidation of the three-tier system has forced distributors to favor

relationships with larger wine producers, leaving smaller wineries to fend

for themselves. The growth cohorts are millennials and Gen Xers, but it’s

still baby boomers and Gen Xers, not millennials, who dominate premium

wine sales (see gure 16).

5

22STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 GENERATIONAL CHANGES AND WINE DEMAND | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

50%

45%

40%

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

Millennials (age 22–38) Gen Xers (age 39–50) Boomers (age 51–68) Matures (age 69+)

19%

36%

38%

7%

The evolution of both consumer preference and price sensitivity

to buy wine across the generations is changing the way wine

is sold — so it is imperative that you evaluate your successful

consumer strategies for emerging signs of weakness. New

strategies must be found, and nding the right one requires

evaluating each cohort’s demand and ability to aord the

wine you’re producing, then scaling that strategy eectively.

Matures

Matures grew up during the Great Depression.

15

Their ensuing

behaviors, such as thriiness, saving and the conservative use of

debt, resulted from their inability to nd employment or even the

bare necessities early in their lives. Add rationing during WWII

to the younger component of the cohort and, decades later, many

still save everything and throw away nothing — ever.

16

Known more as a spirits-and-beer generation, the matures’ wine

consumption t their economic status, and the value of alcoholic

beverages was viewed in part based on alcohol content or the

proof per dollar spent. As a component of purchase, it was very

practical to consider how much alcohol you really were getting

for your money. Wine had a lower alcohol content, so when the

matures purchased wine, they gravitated to low-priced value

wines in large formats.

GENERATIONAL CHANGES AND WINE DEMAND

Figure 16: Cohort share of wine purchased

Source: SVB 2016 Direct-to-Consumer Survey

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 (estimated)

Evaluate your successful

consumer strategies

for emerging signs of

weakness

23STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 GENERATIONAL CHANGES AND WINE DEMAND | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

$35,000

$30,000

$25,000

$20,000

$15,000

$10,000

$5,000

$0

Annual club membership spend

20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 60–69 70–79 80–89 90+

$7,000

$6,000

$5,000

$4,000

$3,000

$2,000

$1,000

$0

Discretionary income

Age

GENERATIONAL CHANGES AND WINE DEMAND

Figure 17: DTC spend by age and gender vs. discretionary income

Source: Customer Vineyards

Female Male

Discretionary income

Baby boomers

Baby boomers represent the largest native population boom

in US history. Reaching drinking age, they rst demonstrated

their thirst for wine, driving the wine coolers trend

17

in the mid-

and late 1980s. Neo-prohibitionism

18

led to short-term declines

in wine consumption through the early 1990s, but beginning

in 1994, with the median boomers reaching 35 and established

in their careers, wine sales started demonstrating strong

volume growth.

To this day, boomers are still the leading consumers of ne wine,

but they are now retiring or nearing retirement (see gure 17).

They are consuming less wine as they age, are changing their

spending patterns in dollars spent and volume consumed and are

evolving from the high price points as they come to grips with

living on a xed income. Today, boomers who built their cellars

over time are more inclined to consume the wine they’ve stored

vs. aging new purchases, which has a negative impact on the

luxury wine market.

When wine club sta ask why a member is leaving the club,

increasingly the answer is “I’m retiring.” That answer should

make wineries with overwhelming shares of boomers in their

clubs reevaluate their current marketing strategies.

When wine club sta ask

why a member is leaving

the club, increasingly the

answer is “I’m retiring”

24STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 GENERATIONAL CHANGES AND WINE DEMAND | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

$300,000

$250,000

$200,000

$150,000

$100,000

$50,000

$0

21–34 35–44 45–54 55–64 65–74 75+Age

$56,368

$97,106

$130,160

$140,686

$105,702

$76,969

GENERATIONAL CHANGES AND WINE DEMAND

Gen X

One of the messages I consistently oer when speaking is

“No matter the cohort, the age where consumers spend the

most in retail falls between 35 and 55.” Gen X is that cohort

today, but they are in second place in terms of consumption

of ne wine. They have the willingness and capacity to buy,

but they lack numbers compared with boomers (see gure 18).

Largely ignored by the retail press, Gen Xers entered the

workforce at a good time economically, and with fewer college

graduates competing for careers compared with the generations

bracketing them, Gen Xers have had a comparatively easy time

building wealth.

Today, Gen X is at the top of income and spending (gure 18).

Their presence has been below the radar, but their consumption

continues to increase. They are perfectly positioned to surpass

baby boomers as the dominant cohort in ne wine consumption

around 2021. With both capacity and willingness, Gen Xers

should be a major focus of winery owners and tasting-room

managers today.

Millennials

Representing 19 percent of current ne wine consumption

19

is the millennial generation, whose outsized impact has been

falsely prognosticated by the wine press

20

for at least a decade.

The unfortunate reality is that while millennials have by all

accounts a better appreciation of wine compared with the other

cohorts at a similar age in development, their appreciation

has not reected itself in ne wine consumption yet because,

to buy anything, a person needs to have both the desire and

the nancial capacity to purchase, and millennials lag prior

generations in terms of buying power.

Figure 18: Median net worth and income of US families

Sources: US Census Bureau, Statistica.com

Median net worth Median income

No matter the cohort, the age

where consumers spend the most

in retail falls between 35 and 55

25STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 GENERATIONAL CHANGES AND WINE DEMAND | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

Index base = 100

Millennials (age 22–38) Gen Xers (age 39–50) Boomers (age 51–68) Matures (age 69+)

GENERATIONAL CHANGES AND WINE DEMAND

One study suggests that a typical college graduate of 2008 has

earned $58,600 less over the following decade in unrecoverable

wages compared with a college graduate of 2007. College

graduates skew high on wine consumption, so that’s a signicant

fact, and there is more negative news for the younger generation.

More millennials today live with parents than with roommates.

Almost two-thirds of them receive some type of nancial support

from their parents for day-to-day living. They carry 300 percent

more student debt than their parents did, and those age 25 to 34

are half as likely to own a home compared with young people

in 1975. With respect to alcohol consumption, the news is mixed.

Still seeking a premium product and a positive experience,

millennials are inclined to substitute cra beer and spirits for

wine, especially on-premise, and are ambivalent as to the place

of origin.

21

The youngest consumer cohort has demonstrated a

propensity for frugal hedonism,

22

meaning they are quite price

conscious but don’t sacrice quality when selecting their adult

beverages. They are looking for the best deal, and price is

paramount in their purchasing decisions, which today skew

to lower-priced oerings. But over time, millennials will

undoubtedly increase their wine consumption, as have the

generations that preceded them (see gure 19).

In an interesting collision of consumer preferences, as

millennials age and become more substantial in the workforce,

they will gradually spend more on wine. At the same time,

retiring boomers will move down the price ladder and into

more-modest bottle prices as they also pull back in their volume

purchased. The result is that both generations will consider price

more important than the average consumer does today. In the

next 10 years, there will be a price range for premium wine sales

where the cohorts meet; that sweet spot will grow and become

important to all wine companies.

23

Our forecast is that the millennial cohort will surpass the

Gen Xers around 2026 to become the largest ne wine–

consuming generation.

Figure 19: Alcohol consumption preferences by generation

Source: Scarborough Research, 2015

Beer in the past 7 days Liquor in the past 7 days Wine in the past 7 days

26STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 GENERATIONAL CHANGES AND WINE DEMAND | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Direct-to-

consumer sales

A casual observer of the business would think that direct

sales have always been an important part of a winery’s

strategy, but that is not the case. Small winery owners

must wear a lot of hats, and while gross margins are

doubled by selling direct, owners have always been most

comfortable growing grapes, making wine and letting the

distributor sell it. But if that’s true, why bother selling

wine directly to the consumer?

6

27STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER SALES | 7 | 8 | 9

DIRECTTOCONSUMER SALES

The simple answer is that selling wine directly to the consumer

has been an aerthought in some eras and a survival require-

ment in others. You’d think the industry would be more strategic

than reactive, but it has been cautious with the evolution of

a DTC strategy. Today perhaps more than at any other time,

the business needs to be out ahead on strategy because for most

wineries the solution will spell the dierence between success

and failure in the coming decade.

Direct sales v1.0

When Prohibition ended in the 1930s, Beringer Vineyards

started wine tours and tastings as a promotional eort to

bring back customers. In the decades that followed, wineries

opened tasting rooms so that

consumers could sample and

purchase their wares. It was

the winery equivalent to the

roadside fruit stand.

Much like Procter & Gamble,

which sent samples of its

products to every mailbox in

the country, wineries saw

a need to deliver samples to

their consumers to support

retail sales in the three-tier

system. Outside of providing a little tax-free cash for the family,

that DTC eort was not about driving direct protability.

Tastings were generally free, and success was measured by how

many people you could get to your tasting room. Legh Knowles,

chair of Beaulieu Vineyard in the Napa Valley, said in the 1980s,

“I have the greatest respect for our customers, but I will admit

the daily touring and tasting doesn’t sell a lot of wine.”

24

Direct sales v2.0

In the late 1980s, with the economy coming o two recessions,

total wine sales were declining due to both neo-prohibitionism

and the aging of the mature generation. Wineries reacted to de-

clining three-tier sales by focusing their eorts on what they

could control, which was the tasting room and, more specically,

developing the wine club concept. It was DTC v2.0, and promotion

wasn’t the reason this time. This iteration was needed for survival.

Winery owners began to recognize the benet of collecting

physical addresses of the people visiting their wineries. Many

started focused US mail campaigns and shipping programs so

that customers could receive wine directly from the winery once

or twice per year. Direct shipping across state lines going into

the early 1990s was quietly growing, despite laws prohibiting it.

In 1996, wineries could legally ship to only 13 reciprocal states

and an additional 17 “personal use” states, many of which

allowed consumers to buy less than a quart of wine annually.

25

Underscoring the absurdity of the laws, more states allowed

people to carry concealed weapons than to purchase wine

directly from the producer. Direct-to-consumer sales were

estimated by some to total less than $100 million per year,

26

and that may be a generous estimate. There were far more

closed states, where consumers could not purchase wine directly,

compared with states in which shipping was legal.

Direct sales v3.0

By 1994, the median baby boomer hit age 35, which is the

magical time historically when consumers begin their serious

consumption careers. Aer almost a decade of declines, US wine

sales took o and distributors started knocking on doors of

even the smallest wineries to meet consumer demand. During the

nineties, it was common to see winery growth rates exceeding

20 percent and wineries completely sold out of wine before the

next release.

27

“I have the greatest respect for our

customers, but I will admit the daily touring

and tasting doesn’t sell a lot of wine.”

28STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER SALES | 7 | 8 | 9

DIRECTTOCONSUMER SALES

With demand refreshed and with less pressure to make the direct

model work, wineries stopped their erstwhile questionable

shipping practices over state lines and sold everything they could

back into the three-tier system. With the selling function again

outsourced to wholesalers, owners stayed home and focused on

growing grapes and making wine.

Wine sold itself, and tasting rooms and wine clubs were only pas-

sively managed. Unlike today, when direct revenue is 60 percent

of the average winery’s sales, through the 1990s direct sales

represented about 20 to 25 percent of total sales for the small

family winery (see gure 20).

Direct sales v3.5

Like ipping a switch, coincident with the short 2001 tech

recession

28

and large 2000 vintage, supply caught up

with demand, and wholesalers, now with a choice, moved

away from selling the product of small wineries.

The wholesaler’s client base had evolved from small chains

and unit retailers toward nationwide big box retailers, and

at that point larger wineries could ll consumer demand.

The prior decade’s playbook was dusted o and, once

again, DTC sales were critical to the survival of smaller

wineries. Tasting-room and wine club activity was again

promoted by owners, but shipping laws were being

enforced, which limited growth.

The industry caught a break with the favorable Granholm

decision in 2005.

29

That ruling knocked the legs out from

under the protectionist state laws that favored in-state

wine producers. Smaller producers would have been put

out of business long ago without the subsequent evolution

of direct shipping, including logistics companies and

those specializing in keeping up with constantly changing

state laws (see gure 21).

Figure 20: Increasing importance of DTC revenue

DTC revenue as a percentage of total revenue

60%

58%

56%

54%

52%

50%

48%

46%

Source: 2016 SVB Annual Wine Conditions Survey

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Figure 21: Direct sales as a percentage of total winery sales

By production size

Source: 2016 SVB Annual Wine Conditions Survey

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

1–2,499 2,500–

4,999

5,000–

9,999

10,000–

24,999

25,000–

49,999

50,000–

99,999

100,000–

249,999

≥ 250,000

2014 2015 2016 2017 (estimated)

29STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER SALES | 7 | 8 | 9

DIRECTTOCONSUMER SALES

While state laws vary — and some permitted state laws can only

be described as arcane if not stealth protectionism — today the

only states to which wineries cannot legally ship are Alabama,

Delaware, Kentucky, Mississippi, Oklahoma and Utah, with Utah

and Kentucky retaining felony anti-shipping laws.

30

Because larger wine companies can attract wholesalers,

dependence on direct-to-consumer sales are less important

to them, but DTC sales for smaller wineries are now the most

critical component of their sales strategy (see gure 22).

The small winery segment has fully grasped the reality that

selling ne wine includes the customer experience. All wineries

are improving their performance in direct sales and are zeroing in

on the use of key performance indicators (KPI)

31

to help execute

on their success.

The number of tasting rooms has increased, and the owner

focus on tasting-room activities and DTC sales has intensied.

Direct revenues continue to climb, but there is a limit to how

far the current strategy will take us.

Can we continue to insist that the consumer come to the tasting

room for an experience? How is that working in malls throughout

the US? In view of clear changes in consumer demand, now is the

time to start thinking about direct sales v4.0.

Figure 22: Premium winery sales growth

Percentage of growth

Source: SVB Peer Group Analysis

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

–5%

–10%

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

(estimated)

28.0

24.0

5.2

4.0

17.6

25.5

19.4

21.2

22.3

2.0

–3.8

19.8

12.2

7.7

9.2

11.9

8.8

9.6

Can we continue to

insist that the consumer

come to the tasting room

for an experience?

30STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER SALES | 7 | 8 | 9

3,000

2,500

2,000

1,500

1,000

500

0

Oregon Washington Napa County Sonoma County Virginia New York

DIRECTTOCONSUMER SALES

Direct sales v3.75: Winery visitation

We have been watching an interesting phenomenon for a few

years now: Tourism is up in the major wine-growing regions.

Hotel stays are increasing, and average room rates are up, as

well. But, with the exception of Oregon, Virginia and New York,

average winery visitation is down (see gure 23). How do you

explain the paradox of more tourism in a wine region but lower

visitation to the wine-tasting rooms?

In 2015, we were uncertain about the cause of the trend because

the negative direction made no sense in light of higher tasting-

room income, better wine club metrics and the increasing focus

that wineries were putting on DTC sales. We suspected that the

negative trend might simply be better reporting from wineries

that were focusing more on their KPI, but we weren’t certain and

could not take a position.

In 2017, we started hearing more wineries quietly lamenting

declining visitation. Aer additional research and reection,

we are convinced that there is more going on than we rst

suspected. Tasting-room revenue is up, but what is driving that

higher revenue is improved average purchases. Wineries

are doing a better job of selling to the guests they host, but the

number of visitors is nevertheless declining, and we believe

there are several reasons why.

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 (estimated)

Figure 23: Changes in monthly visitor counts

Sources: 2013–2016 SVB Annual Wine Conditions Surveys

How do you explain the

paradox of more tourism

in a wine region but

lower visitation to the

wine-tasting rooms?

31STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER SALES | 7 | 8 | 9

3,500

3,000

2,500

2,000

1,500

1,000

500

0

Number of openings

Before 1982 1983–1987 1988–1992 1993–1997 1998–2002 2003–2007 2008–2012 2013–2017

DIRECTTOCONSUMER SALES

The rst issue is the number of tasting rooms being opened

(see gure 24). Prior to 2000, growers didn’t always include a

tasting room when they established a winery; but as new winery

formations have slowed over the past ve years and direct sales

have become critical, tasting-room openings have accelerated,

with more existing wineries opting to employ duplicate type 02

licenses. This has started a discussion in several communities

regarding the rapid growth of downtown tasting rooms.

32

Average tasting-room fees have been increasing at a steady

pace for years — and for decades on California’s North Coast

(see gure 25). Each year, wineries ask themselves if they can

increase their fees. They see tasting-room revenue up, review

comps from neighboring wineries and then decide to raise

their rates. At some point, that tasting fee becomes a deterrent,

and in some cases we have reached that point.

The aging of the consumer is also playing a role. Older customers

with declining discretionary income have been to wine country.

They used to come, taste for free at as many places as they could

visit and then leave town with wine in the trunk. Today, they plan

where they are going to go, have a bucket list of places to see,

stay at a nice hotel and also factor in food, shopping and other

regional entertainment. Because the visit is planned and they

aren’t going to so many tasting rooms, they are more likely to buy

at the wineries they plan to visit. The bottom line, though, is that

they aren’t visiting as many wineries.

Figure 24: Historic openings of wineries and tasting rooms

Sources: SVB 2017 Direct-to-Consumer Survey and SVB analysis

WineryTasting room

Figure 25: Annual changes in tasting fees

Source: SVB 2017 Direct-to-Consumer Survey

$35

$30

$25

$20

$15

$10

$5

$0

Standard Reserve

$12.31

$13.76

$14.48

$15.84

$25.97

$26.33

$28.90

$32.61

2013 2014 2015 2016

At some point, that tasting

fee becomes a deterrent,

and in some cases we have

reached that point

32STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER SALES | 7 | 8 | 9

Younger consumers are shrewd in their planning of a wine

country visit. A group of four is unlikely to pay a reserve tasting

fee in Napa or Sonoma because that might amount to what they

budgeted for their dinner together (see gure 26). They will

share tastings, if allowed, and will nd as many ways as possible

to reduce their total spend while retaining the experience level.

Still in a discovery mode, they will scout out tasting-fee struc-

tures and reimbursement policies beforehand or will negotiate

at the counter. Like older consumers, they aren’t bound to

visiting as many wineries as possible and will look for other

entertainment, as well.

For the young frugal-hedonist consumer, high tasting fees are

a clear deterrent and are part of the reason why Oregon is still

growing average visitation while Napa and Sonoma are not.

DIRECTTOCONSUMER SALES

Figure 26: Winery visitor sales and fees

Source: SVB 2017 Direct-to-Consumer Survey

Oregon Washington Napa County Sonoma County

Average tasting-room purchase

$77 $69 $304 $140

Standard tasting fees $13 $9 $38 $21

Reserve tasting fees $25 $18 $66 $39

Net wine club growth rate 10.8% 14.0% 12.7% 13.9%

Annual visitation growth (2013–2016) 3.0% –7.9% –2.8% –6.0%

For the young frugal-hedonist consumer,

high tasting fees are a clear deterrent and are part

of the reason why Oregon is still growing average

visitation while Napa and Sonoma are not

33STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER SALES | 7 | 8 | 9

Retail evolution

Pinpointing the exact cause or source of large-scale change

is never easy, and the earlier you predict it, the more

dicult it is to support the prediction. In the case of the wine

business, this year’s changes can be tied to several causes,

some of which are reected in retail and luxury sales overall.

7

34STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 RETAIL EVOLUTION | 8 | 9

Much of the disruption we see in retail is due to shiing consumer

shopping behaviors — from how they shop via dierent digital

and physical platforms to dierences in the way they value

goods and experiences. This disruption has le manufacturers

and retailers struggling to adapt; but to keep up, they must rst

understand where dollars are being spent and how to tap in to

changing shopping habits to drive growth.

The Amazon eect

Most commentators, no matter their political aliations, would

agree that the US economy has recovered from the recession.

Yes, there are dierences in this economy vs. the one that

preceded 2007, but we can all say that at this moment the US

economy is “good,” and good means we are seeing enhanced

sales opportunities as we move into 2018. But underneath the

positive news, there are evolutionary changes taking place in

both the consumer and the way retail is transacted.

In 2017, countless brick-and-mortar retail establishments closed,

including JCPenny (138 stores), Kmart and Sears holdings

(300+ stores), Macy’s (68 stores), HHGregg (220 stores), MC

Sports (68 stores), Payless ShoeSource (800 stores) and many

others.

33

But the poster child for this disruption is bookstore

chain Borders, which was the early sacrice to the Amazon

eect, also known as digital Darwinism.

34

Amazon is by far the largest e-commerce player, with 44 percent

of estimated online sales. Some of the above-mentioned stores

are working hard to catch up — getting their online retail

presence competitive — and nding success, whereas others

have led for bankruptcy.

How does that relate to wine? Many of the stores above were late

to recognize both the threat and the opportunity of e-commerce.

Borders in particular is a case study for the wine industry of what

not to do.

• Borders saw e-commerce as an extension of what it did, rather

than a replacement of what it oered. It outsourced its sales

to Amazon, believing that internet sales were a nice-to-have,

instead of a critical component of success.

• Borders didn’t foresee the evolution and acceptance of

alternative digital delivery platforms for its products.

• It focused its strategy on the experience in its physical

locations, ignoring the online experience.

• Like many companies that disappear, Borders took on too

much debt to execute on its physical store expansion.

• And nally, to compete Borders decided to expand from

books into music, which is something it didn’t know about,

and it totally missed the oncoming competition in the

iPod revolution.

35

In the end, Borders was inhaled by consumer and digital

disruption by both Amazon and Apple, two tech behemoths

of our day. There is a lesson in that for the wine business.

RETAIL EVOLUTION

Borders in particular

is a case study for

the wine industry of

what not to do

35STATE OF THE WINE INDUSTRY 2018

CONTENTS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 RETAIL EVOLUTION | 8 | 9

Direct sales v4.0

In the mid-1990s, the internet took hold. Wineries put up

websites with their contact information and directions to their

locations. Amazon started selling books online in 1995, and

PayPal came around to help with payments in 1998. Wineries

added shopping carts in 2002 and experimented with online

sales, but online DTC has never been successful for winemakers.

Today, e-commerce represents about 10 percent of total US retail

sales (see gure 27),

36

with Amazon accounting for nearly half of

that. While wineries have gravitated to DTC sales, it is old-school

sales without current e-commerce tools. With only 3 percent of

today’s winery sales true online purchases, how can we say that

wineries are really focused on DTC sales?

Here are a few facts:

• Wineries still focus on their clubs as their customer universe,

instead of on all wine consumers.

• Few wineries have an online presence that engages the

customer. Sites lack sophisticated, responsive, fully integrated

designs and experiences that allow new and returning

customers frictionless e-commerce.

• Winery websites are almost static, and, with the exception of

basic Google tracking, they don’t harvest visitor information

or put it to use for responsive experiences, retargeting and

modern FOMO (fear of missing out) tools.

• Online product marketing is rudimentary, lacking a push to

consumers who might index high on Google search results.

There is virtually no focus on turning Instagram followers into

micro-evangelists or deploying targeted Facebook ads.

• The opportunity is wide open for a company using online tools

to replace the distributor’s sales and marketing role.

37

• Digital products that integrate with customer relationship

management and the wine club — and that can deliver

scalable marketing messages for dierent buying personas

over mixed platforms — simply do not exist.

• There is virtually no investment currently for online

acquisition and retention of potential wine customers and

no management of the larger universe of prospects.

38

• The use of big data to enhance outreach to consumers and

improve sales opportunities is not employed at all.

39

Figure 27: Growth in e-commerce sales

Millions of dollars

Source: US Census Bureau

$140,000

$120,000

$100,000

$80,000

$60,000

$40,000

$20,000

$0

Q1/2009

Q2/2009

Q3/2009

Q4/2009

Q1/2010

Q2/2010

Q3/2010

Q4/2010

Q1/2011

Q2/2011

Q3/2011

Q4/2011

Q1/2012

Q2/2012

Q3/2012

Q4/2012

Q1/2013

Q2/2013

Q3/2013

Q4/2013

Q1/2014