Study on the Contribution of Sport

to Economic Growth and

Employment in the EU

Study commissioned by the European Commission,

Directorate-General Education and Culture

Final Report

November 2012

SportsEconAustria (SpEA, Project lead)

Sport Industry Research Centre (SIRC) at Sheffield Hallam University

Statistical Service of the Republic of Cyprus

Meerwaarde Sport en Economie

Federation of the European Sporting Goods Industry (FESI)

Ministry of Sport and Tourism of the Republic of Poland

Contents

1 Executive Summary 1

2 Introduction 7

3 Developing Sport Satellite Account Systems in Europe 9

3.1 Satellite systems in the National Accounts ..................................................................... 9

3.2 An Input-Output Table: Sport ........................................................................................ 10

3.3 Analysis of the Economic Effects of Sport .................................................................... 10

3.3.1 Calculation of the Value-Added Effects of Sport ................................................. 10

3.3.2 Calculation of the Purchasing Power Effects of Sports ....................................... 10

3.3.3 Calculation of the Employment Effects of Sport .................................................. 11

3.3.4 Calculation of Multiplier Effects ........................................................................... 11

4 Definition of Sport in the Economic Sense 13

5 Set up of a Multiregional Input-Output Table: Sport 17

5.1 National Input-Output Tables ........................................................................................ 18

5.1.1 Calculation of Input-Output Tables ...................................................................... 23

5.1.2 The Input-Output Table of Malta .......................................................................... 29

5.2 Collection of National Sports Data ................................................................................ 31

5.3 Imports and Exports ..................................................................................................... 32

5.4 Enlarging national Input-Output Tables ........................................................................ 32

5.5 Multiregional Input-Output Table according to Chenery and Moses ............................. 34

5.6 Finalisation of the Multiregional Input-Output Table ..................................................... 37

6 European and International Data Sources 40

6.1 Production .................................................................................................................... 40

6.2 Sport-related Public Administration and Social Security, CPA 75 ................................. 41

6.3 Sport-related Education, CPA 80 .................................................................................. 41

6.4 Sport-Related Health, CPA 85 ...................................................................................... 42

6.5 The European Market for Sport Articles ....................................................................... 42

6.6 Import and Export Data ................................................................................................ 44

6.7 Additional Service and Goods Data .............................................................................. 48

6.8 Further Calculations ..................................................................................................... 49

7 Remarkable Matters 51

7.1 Prior Publications .......................................................................................................... 51

7.2 German Data ................................................................................................................ 51

7.3 Input-Output Table: Sport of France ............................................................................. 52

7.4 Issues related to Input-Output Tables ........................................................................... 55

7.5 International Trade Data ............................................................................................... 56

8 Employment 57

9 Strength/Weakness Analysis in a Country Comparison 62

9.1 Relative Strength and Weakness in the Goods and Services Sectors ......................... 63

9.2 Conclusion of Strengths and Weaknesses ................................................................... 65

10 Analysis of Growth Potentials 66

10.1 Common Growth Potentials .......................................................................................... 66

10.1.1 Sports Nutrition ................................................................................................ 66

10.1.2 Sports Insurance ............................................................................................. 67

10.1.3 Economic and Legal Consultancy ................................................................... 69

10.2 Country Growth Potentials ............................................................................................ 70

11 Identification of Key Sectors 72

12 Range of products 75

13 Macroeconomic Effects of Sport - European Union 77

13.1 Gross value added ....................................................................................................... 77

13.2 Employment .................................................................................................................. 78

13.3 Sector-specific multipliers ............................................................................................. 79

14 Macroeconomic Effects of Sport - National Results 83

14.1 Austria .......................................................................................................................... 84

14.1.1 Gross value added .......................................................................................... 84

14.1.2 Employment .................................................................................................... 85

14.1.3 Sector-specific multipliers ................................................................................ 85

14.2 Belgium ......................................................................................................................... 87

14.2.1 Gross value added .......................................................................................... 87

14.2.2 Employment .................................................................................................... 88

14.2.3 Sector-specific multipliers ................................................................................ 88

14.3 Bulgaria ........................................................................................................................ 90

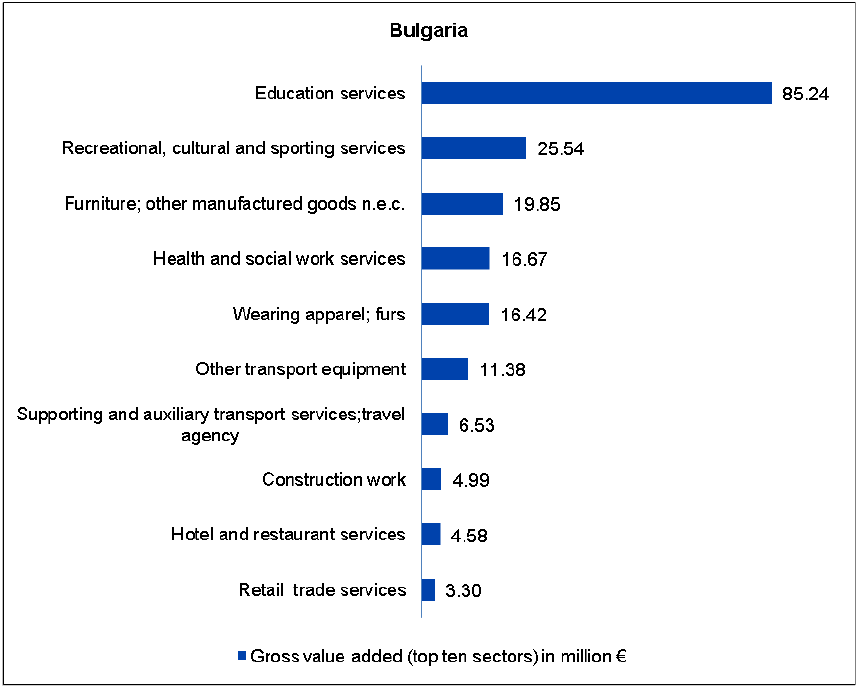

14.3.1 Gross value added .......................................................................................... 90

14.3.2 Employment .................................................................................................... 91

14.3.3 Sector-specific multipliers ................................................................................ 91

14.4 Cyprus .......................................................................................................................... 93

14.4.1 Gross value added .......................................................................................... 93

14.4.2 Employment .................................................................................................... 94

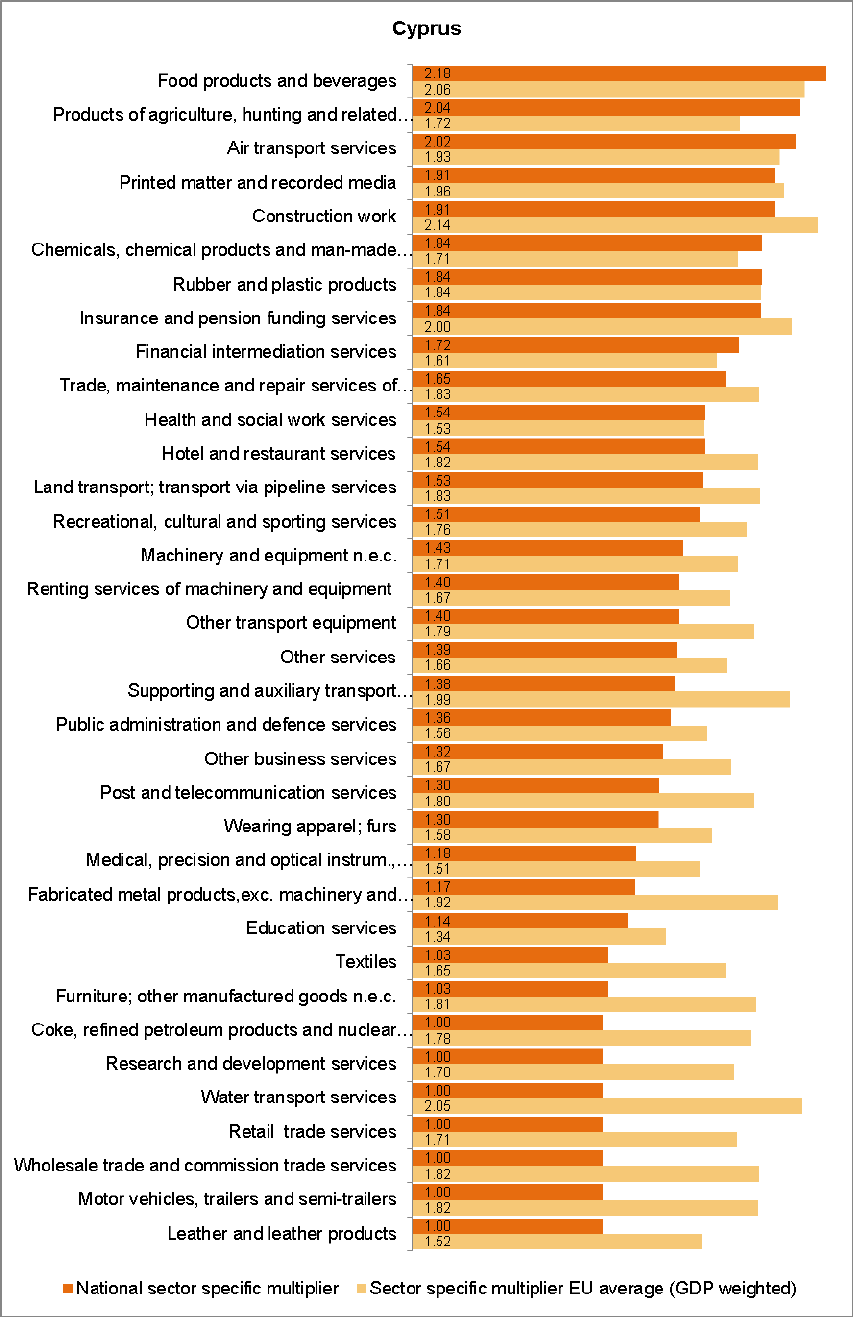

14.4.3 Sector-specific multipliers ................................................................................ 94

14.5 Czech Republic ............................................................................................................ 96

14.5.1 Gross value added .......................................................................................... 96

14.5.2 Employment .................................................................................................... 97

14.5.3 Sector-specific multipliers ................................................................................ 97

14.6 Denmark ....................................................................................................................... 99

14.6.1 Gross value added .......................................................................................... 99

14.6.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 100

14.6.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 100

14.7 Estonia ........................................................................................................................ 102

14.7.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 102

14.7.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 103

14.7.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 103

14.8 Finland ........................................................................................................................ 105

14.8.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 105

14.8.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 106

14.8.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 106

14.9 France ........................................................................................................................ 108

14.9.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 108

14.9.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 109

14.9.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 109

14.10 Germany .................................................................................................................... 111

14.10.1 Gross value added ......................................................................................... 111

14.10.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 112

14.10.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 112

14.11 Greece ...................................................................................................................... 114

14.11.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 114

14.11.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 115

14.11.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 115

14.12 Hungary .................................................................................................................... 117

14.12.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 117

14.12.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 118

14.12.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 118

14.13 Ireland ....................................................................................................................... 120

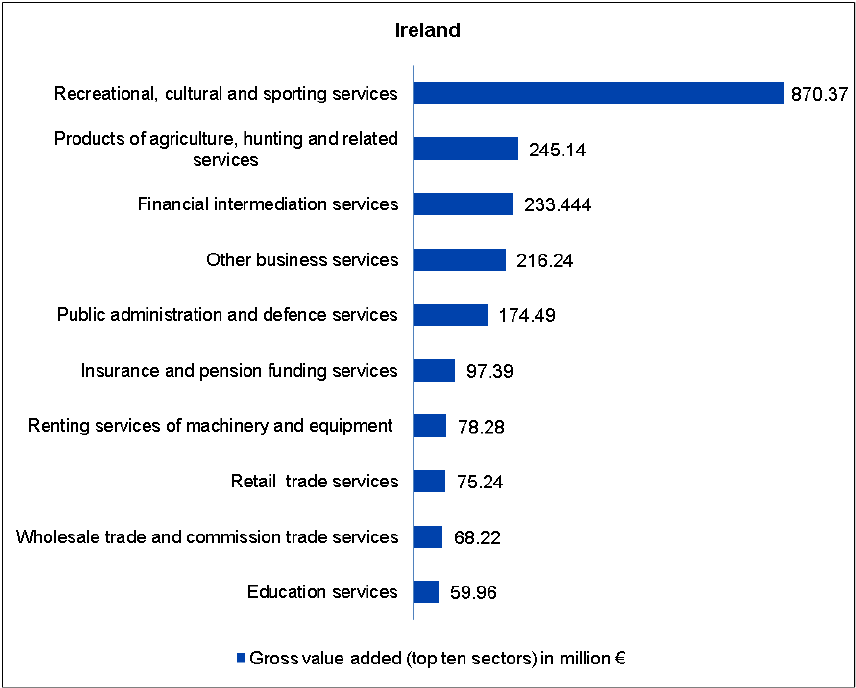

14.13.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 120

14.13.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 121

14.13.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 121

14.14 Italy ........................................................................................................................... 123

14.14.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 123

14.14.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 124

14.14.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 124

14.15 Latvia ........................................................................................................................ 126

14.15.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 126

14.15.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 127

14.15.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 127

14.16 Lithuania ................................................................................................................... 129

14.16.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 129

14.16.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 130

14.16.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 130

14.17 Luxemburg ................................................................................................................ 132

14.17.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 132

14.17.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 133

14.17.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 133

14.18 Malta ......................................................................................................................... 135

14.18.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 135

14.18.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 136

14.18.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 136

14.19 The Netherlands ....................................................................................................... 138

14.19.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 138

14.19.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 139

14.19.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 139

14.20 Poland....................................................................................................................... 141

14.20.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 141

14.20.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 142

14.20.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 142

14.21 Portugal .................................................................................................................... 144

14.21.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 144

14.21.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 145

14.21.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 145

14.22 Romania ................................................................................................................... 147

14.22.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 147

14.22.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 148

14.22.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 148

14.23 Slovakia .................................................................................................................... 150

14.23.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 150

14.23.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 151

14.23.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 151

14.24 Slovenia .................................................................................................................... 153

14.24.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 153

14.24.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 154

14.24.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 154

14.25 Spain......................................................................................................................... 156

14.25.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 156

14.25.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 157

14.25.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 157

14.26 Sweden ..................................................................................................................... 159

14.26.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 159

14.26.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 160

14.26.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 160

14.27 United Kingdom ........................................................................................................ 162

14.27.1 Gross value added ........................................................................................ 162

14.27.2 Employment .................................................................................................. 163

14.27.3 Sector-specific multipliers .............................................................................. 163

15 List of Figures 165

16 List of Tables 169

17 Bibliography 171

17.1 Methods and Data: ..................................................................................................... 171

17.2 Satellite Accounts and Sport Economics .................................................................... 174

17.3 Sources of Statistic: .................................................................................................... 175

Annex: National Data Sheets 176

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 1 -

1 Executive Summary

The Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment in the

European Union was carried out in 2011-2012, based on data collection in all 27 EU Member

States focussing on sport as an economic activity. The methodology utilised a specific

adaptation of the National Accounts of the Member States, using these accounts to make a

Multiregional Input-Output Table: Sport (MRIOT:S) which is based on 27 national Input-

Output Tables: Sport. This means that the chosen approach is consistent with the National

Accounts on the one hand and intra-EU trade on the other.

National Accounts are the main reference point for economic policy making on the national

macro level and are normally maintained by the statistical office of a country. A satellite

account is an extension of the standard national account system. A Sport Satellite Account

(SSA) – being the core of an Input-Output Table: Sport – filters the National Accounts for

sport-relevant activities to extract all sport-related figures while maintaining the structure of

the National Accounts. The instrument of SSAs permits all sport-related economic activities

to show up explicitly, rather than keeping them concealed, in deeply disaggregated (low-

level) classifications of the National Accounts.

1

Hence one of the results of the study is an Input-Output Table: Sport for each Member State.

Most of these Input-Output Tables: Sport are proxy tables and should therefore be used with

caution. They were designed for EU-wide analysis and cannot replace Input-Output Tables:

Sport produced at national level. Noticeably, such national SSAs and Input-Output Tables:

Sport, of direct relevance for this study, have already been developed in several EU Member

States based on the statistical definition of sport agreed by the EU Working Group on Sport

and Economics in 2007 ("Vilnius Definition of sport"). To further improve the data quality, all

Member States are strongly encouraged to produce a fully-fledged national Input-Output

Table: Sport. Once this is done by a country, it should then replace the remaining proxy Input-

Output Table: Sport in the MRIOT:S.

The importance of such a fully-fledged national Input-Output Table: Sport, however,

surpasses the mere use within the MRIOT:S. The latter was designed and created in such a

way that it serves EU-wide policy analyses while the national results are secondary. A

country that has a fully-fledged national Input-Output Table: Sport, in contrast, can evaluate

national policies in much more detail. Distinctive features can be incorporated quickly which

are not so easily reflected in the EU-wide MRIOT:S with its need for a common standard. The

already existing fully-fledged national Input-Output Table: Sport can serve as examples as

they are in widespread and intense use by the respective policy makers.

Two central goals of this study are to establish a consistent data base to serve as a

reference point for subsequent analyses, and to generate a comprehensive estimate of the

magnitude of sport-related value added and employment in Europe. As such, the work will

1

The name Sport Satellite Account is derived from the tabular presentation of the account (i.e. as a matrix). In this format, the

sport-related rows and columns wrap around the non-sport part, circling around it like a satellite.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 2 -

contribute to EU policy and its strategic goals in the Europe 2020 context. It was found that

sport overall is labour-intensive. Growing the sport-related economy thus leads to a more

than proportional growth of employment. In addition, a number of promising sectors were

identified which are currently comparatively small while showing strong connections to the

rest of the economy. Their below-average size indicates growth potential while at the same

time they send out strong impulses to many other sectors.

The main study findings can be summarised as follows:

Sport's share in total gross value added

The Vilnius Definition of sport distinguishes between a statistical, a narrow and a broad

definition of sport as follows:

Statistical Definition: comprised of NACE 92.6 Rev. 1.1 ("Sporting activities", the only

part of the sport sector having its own NACE category).

Narrow Definition: all activities which are inputs to sport (i.e. all goods and services

which are necessary for doing sport) plus the Statistical Definition.

Broad Definition: all activities which require sport as an input (i.e. all goods and

services which are related to a sport activity but without being necessary for doing

sport) plus the Narrow Definition.

The results of the study show that the share of sport-related gross value added of total EU

gross value added is 1.13% for the narrow definition and 1.76% for the broad definition of

sport. The share of what is generally known as the organised sport sector (sport clubs, public

sport venues, sport event organisers) is reflected in the statistical definition. The share of

gross value added according to the statistical definition is 0.28%. Therefore the real share of

sport in terms of production and income is about six times as high as reported in official

statistics.

In 2005, sport-related gross value added (direct effects) amounted to 112.18 bn Euro

according to the narrow definition and 173.86 bn Euro with respect to the broad definition.

For the statistical definition of sport it was 28.16 bn Euro.

The direct effects of sport, combined with its multiplier (indirect and induced) effects, added

up to 2.98% (294.36 bn Euro) of overall gross value added in the EU.

The highest sport-related value added was found in the sector Recreational, cultural and

sporting services, followed by Education services (second), and Hotel and restaurant

services (third).

The average gross value added of the statistical definition shows a broad division between

high income Western European Member States and lower income Eastern states. In

absolute terms, the gross value added per capita in the Eastern Member States is around

5 Euro to 10 Euro per capita for this part of the sport industry, while in the higher income

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 3 -

states, this amount is around 50 Euro to 100 Euro per capita. Of course it could be expected

that richer countries spend more on sport than poorer countries, but this is true not only in an

absolute sense but also in a relative sense: the share of gross value added of sport is lower

in low income EU Member States compared to high income states. On a cross-section basis,

the national income elasticity of sports is 1.14, which means that if national income rises by

1%, the gross value added related to sport rises by 1.14%.

From an analysis of specific sectors that are important in enhancing the size of the sport

industry, three sectors stand out:

Tourism

Fitness and the media

Education

- Tourism: for some countries, a substantial contribution to the sport industry share is made

by the hotel and restaurant sector. This is especially true for Austria, Germany, Italy, and

Sweden, which are important destinations for active sports holidays. In Germany and

Sweden a large part is probably generated by domestic tourism, but for the other countries

international tourism is a major source of income. As these countries have a specific supply

advantage and the elasticity of income for sports consumption is above 1, their sports

economic base is likely to be strengthened when European economies grow.

- Fitness and the media: in some North-Western European countries a large part of the total

demand for sport activities is satisfied by commercial sports suppliers such as fitness clubs.

This is true in Sweden and the Netherlands. Another demand-related issue is the strength of

professional football and the role of the media in the UK, where pay television for football

matches has grown into a significant economic activity.

- Education: in almost all countries sport education is an important part of the total sport

economy. However, there are a few exceptional countries. These are Denmark, Estonia and

Latvia which have exceptionally high shares of sport education in sport-related gross value

added. These Member States seem to attach a high value to sport in an educational context.

Employment effects

For the EU as a whole, the contribution of sport-related employment to total employment is

2.12%. In absolute terms this is equal to 4.46 m employees. This is above the sport-related

share in gross value added (1.76%), which indicates that sport is labour-intensive.

The largest number of sport-related jobs can be found in Germany, which has 1.15 m sport-

related jobs or nearly 27% of all sport-related jobs in the EU. The runner-up is the UK, with

more than 610,000, followed by France with more than 410,000 jobs in sport.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 4 -

Sectoral interrelatedness

Multipliers are measures of the degree to which the sectors in an economy are interrelated.

Sectoral multipliers measure the impact in total economic activity generated by a one-unit

change in one sector. The value of a sectoral multiplier is determined by the links on the one

hand and the leakages on the other hand within an economic system. Sectors with strong

relations to the rest of the domestic economy and few imports report high multipliers. If an

impulse to a sector is hardly transferred to other branches or leaves the country (imports of

intermediate goods), the multiplier barely exceeds its minimum value of 1. The study shows

that smaller Member States have significantly lower mean sectoral multipliers than larger

Member States.

The highest multipliers are found in the construction branch and in sectors related to tourism

(hotels, air transport). Education has a relatively low multiplier as it requires only a few

intermediate goods compared to its wages, but it is an important sector in the whole network

of value creation in sports, especially in the Nordic and Baltic countries.

Sectoral growth potentials

The study analyses several sectors for their growth potential and differences between

countries are discussed. A general pattern of sport production can be observed in the sense

that sport services are predominantly produced for the domestic market while sportswear is

predominantly imported. For sports durables internal EU specialisation can be found.

There are three sectors that play a special role in almost all countries: food products and

beverages; construction; and supporting and auxiliary transport services including travel

agency services. These sectors have strong linkages to the rest of the economy and are

therefore strategically important.

The most important policy implications to be drawn from the outcomes of this study are listed

hereafter.

Policy Implication 1: Sport is an important economic sector

The study shows that sport is an important economic sector in the EU, with a share in the

national economies which is comparable to agriculture, forestry and fishing combined.

Moreover, its share is expected to rise in the future.

Policy Implication 2: Sport represents a labour-intensive growth industry

Sport is a relatively labour-intensive industry. This means that the expected growth in the

sport industry is likely to lead to additional employment, with sport's share of total

employment being higher than its share of value added. The sport sector can thus contribute

to fulfilling the Europe 2020 goals.

Policy Implication 3: Sport can foster convergence across EU Member States

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 5 -

Sport has the economic characteristics of a luxury good, with an income elasticity above 1.

This implies that sport production and services will grow faster in lower income countries

than in higher income countries. It thus contributes to the economic convergence of Member

States and can help reduce economic imbalances.

Policy Implications 4: Sport has growth-enhancing specialisation advantages

Sport products and services can be found in many other sectors, e.g. in tourism, insurance,

legal consultancy, and many more. This means that sport can help specific niche sectors to

develop, depending on the characteristics of sport demand and supply in a specific country.

Examples of such specialisation patterns can be observed in the UK (professional sports and

betting), in Austria (tourism) and in Northern Europe (education). Further study and

identification of these patterns may help to enhance the sector’s contribution to the Europe

2020 Strategy.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 6 -

Annex: Key indicators per Member State

As explained above, the figures in this table should be seen as proxies produced for the sake

of EU-wide analysis unless stated otherwise. While they represent a first set of indicative

figures produced for all EU Member States according to a single methodology, they should

be used with caution. Figures for Austria, Cyprus, Poland and the UK reflect those countries'

Sport Satellite Accounts, not necessarily based on 2005 as the other values do.

Table 1: Sport related gross value added and employment. All values correspond to

the Broad Definition and contain direct effects only

Value added

Employment

in million Euro

in heads

Austria

2

10,730

242,968

Belgium

3,043

71,416

Bulgaria

223

55,843

Cyprus

3

310

7,600

Czech Republic

1,062

89,119

Denmark

3,719

69,287

Estonia

162

15,686

Finland

2,654

74,209

France

21,607

416,537

Germany

46,677

1,146,234

Greece

2,518

70,878

Hungary

778

55,577

Ireland

2,377

40,532

Italy

15,599

329,860

Latvia

136

17,077

Lithuania

161

16,178

Luxembourg

697

19,331

Malta

93

3,070

Netherlands

5,828

141,896

Poland

4

5,300

225,500

Portugal

1,534

72,101

Romania

790

161,248

Slovakia

472

49,910

Slovenia

521

28,576

Spain

10,407

336,177

Sweden

2,360

73,266

UK

4

39,860

632,400

Source: SportsEconAustria, Sport Industry Research Centre at Sheffield Hallam University, Statistical

Service of the Republic of Cyprus, Meerwaarde Sport en Economie, Ministry of Sport and Tourism of

the Republic of Poland.

2

According to the national Input-Output-Table Sport of 2005.

3

According to the national Input-Output-Table Sport of 2004. Data of 2005 were used in the calculations.

4

According to the national Input-Output-Table Sport of 2006. Data of 2005 were used in the calculations.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 7 -

2 Introduction

This study assesses the macroeconomic importance of sport in the EU-27, in particular its

growth and employment potential, thereby making a contribution to assess the sector’s role

with respect to the Europe 2020 strategy.

The European Commission has formulated the Europe 2020 strategy to meet future

challenges. It is the “EU’s growth strategy for the coming decade”.

5

Part of this strategy is to

identify specific economic risks and opportunities within the EU. As a result of the Lisbon

Treaty “The Union shall have competence to carry out actions to support, coordinate or

supplement the actions of the Member States. The areas of such action shall, at European

level, be: […] (e) education, vocational training, youth and sport”

6

. To illustrate the role of

sport with regard to “Europe 2020”, knowledge about the specific characteristics of sport

economics and its impact on Europe’s economy is necessary. Although there is some data

available on this, the Commission’s 2007 White Paper on Sport noted the lack of

comprehensive and comparable EU-wide information in order to develop evidence-based

policies.

From its inception in 2006, the EU Working Group "Sport & Economics" has developed a

harmonised definition of sport (“the Vilnius Definition of sport”) and a common methodology

to measure the economic importance of sport (the “Sport Satellite Account” – SSA). A

complete picture of the economic importance of sport for the EU as a whole through the

aggregation of 27 national sport satellite accounts can only be expected in the longer term,

since this approach is a complex and time-consuming task and therefore faces national

budgetary and human resource constraints.

Meanwhile, a macro-economic approach was developed alongside national efforts to

implement sport satellite accounts to get methodologically sound data based on the Vilnius

Definition of sport. This can enhance the overview of the total EU sport economy and

overcome the partial scope of national satellite accounts. It can also stimulate

methodological discussion among Member States, which help to raise the quality and the

comparability of national estimates of SSAs. For these reasons, this study was undertaken.

The study focused on the following research questions:

What is the economic importance of sport in terms of gross value added?

What is the economic importance of sport in terms of employment?

What similarities and differences can be observed between Member States for these

variables and how can these be explained?

What are national strengths and weaknesses?

Where are the growth potentials?

5

Source: http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/index_en.htm, found on 5 March 2012.

6

Treaty of Lisbon, Article 2 E.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 8 -

Noticeably, four members of the EU Working Group “Sport & Economics” and the Expert

Group “Sport Statistics” – Austria, Cyprus, Poland and the United Kingdom – have already

finished their work on national SSAs which formed a valuable basis for this study.

The report is divided into four large parts:

The introductory chapters:

o Input-Output Analysis in general as well as Satellite Accounts are discussed

in Chapter 3.

o The economic definition of sport is explained in Chapter 4

Descriptions of background theory and practical implementation of the model

and the surrounding calculations:

o At first, Multiregional Input-Output Analysis is discussed (Chapter 5), with the

focus on how to connect stand-alone regional Input-Output Tables.

o The different data sources are described in Chapter 6.

o Several topics worth mentioning are covered in Chapter 7.

Interpretation of the results: EU-wide analyses of the sport-related economy are

discussed first, such as

o employment (Chapter 8),

o strengths and weaknesses (Chapter 9),

o growth potentials (Chapter 10),

o key sectors (Chapter 11), and

o the range of products (Chapter 12).

This is followed by the description of macroeconomic effects on

o the European Union in total (Chapter 13) as well as on

o all single Member States (Chapter 14).

An annex containing national data sheets forms the end of the report.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 9 -

3 Developing Sport Satellite Account Systems in Europe

3.1 Satellite systems in the National Accounts

For several economic and societal questions or problems it is necessary to modify the clarity

and presentation of the existing statistical data in order to enable better data analysis and

facilitate further calculations.

Specialized tables (more detailed Input-Output Tables) have been developed to cover certain

areas of the economy. These extensions of the national accounts thematically “orbit” around

the basic tables – that is why they are called “satellite systems” or “satellite accounts”.

Haslinger

7

provides a general definition of a satellite account system: "A Satellite Account

System is a consistent system of monetary and non-monetary measurement categories

made at regular intervals. These should verify conditions and procedures – correlated with

important societal requests – in detail."

Stahmer

8

introduces a different definition by stating that satellite systems are specific data

systems, which are designed to answer specific economic questions but have a close

connection to the national accounts and hence enable detailed economic analysis.

A “sport satellite account system” includes all economic effects (gross domestic production,

value-added and employment) due to any sport-related activity generated by the various

economic sectors and shows them consistent with the terms of the national accounts.

Accordingly a “sport satellite account system” provides all the economic effects linked to

sport-related activities (which are not included in a proper and detailed form in the national

accounts) in a consistent form.

A complete economic analysis of sport also includes the sport-related indirect and induced

effects caused by the direct sport-related activities. These indirect effects can be sub-divided

into:

- Multiplier effects, which were generated by the demand for intermediate inputs of the

sport-related sectors, for example showers for swimming pools or leather for saddles,

- changes in the capital stock by investments into the sport sectors, for example

special cutting machinery to produce sporting boat hulls, and

- income effects, that arise because sport-related earnings enable higher consumer

expenditures by those working in the sport industry.

7

Haslinger (1988), S. 66

8

Stahmer (1991) S. 45

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 10 -

These indirect economic effects again lead to multiplier effects and higher earnings. The

process thus repeats itself. To quantify the total economic impact of sport it is necessary to

sum up the direct effects and the multiplier effects.

Due to the complete compatibility of the satellite account with the national accounts, a

comparison of important macroeconomic aggregates of the sport sector (e.g. gross value-

added, employment) with macroeconomic aggregates of other economic sectors is made

possible.

3.2 An Input-Output Table: Sport

To establish a sports satellite account in the EU-27 countries and to use them in order to

analyse the effects of sport on national economies, it is useful to combine them with the

particular national Input-Output Tables, leading to an “Input-Output Table: Sport”.

Input-Output analysis is one of the most known and used tools of economic analysis. Input-

Output models are systems of linear equations, where each of them describes a different

product allocation of the economy. An Input-Output Table describes the structure of the

economy, and the various relations between the different sectors of an economy, and helps

to quantify the multiplier effects for the national economy.

Implementation of a sport satellite account and combination with the national Input-Output

Table results in a methodological tool that shows the sport-related activities and their various

links with the economy. Hence a sport satellite account is a means to answer important

(sport-related) economic questions within European society in a scientific way.

3.3 Analysis of the Economic Effects of Sport

On the basis of the Input-Output Table: Sport, the sport-related impact on the national

economy can be determined. These further calculations result in sport-related gross National

Product and sport-related employment – as well as the direct and indirect sport-related

effects (multiplier effects) on the value-added, the purchasing power and the labour market.

3.3.1 Calculation of the Value-Added Effects of Sport

The value-added of a sector is the difference between total production and the inputs needed

to generate this production. To quantify these direct value-added effects, information on

income and expenditure in sport, as well as investment, is necessary. By subtracting the

payments for the inputs from the expenditures, the direct value-added effect is obtained. By

applying the appropriate multipliers, the direct and indirect value-added effects are obtained.

3.3.2 Calculation of the Purchasing Power Effects of Sports

For the quantification of the direct effects on purchasing power, the expenditures for

investments and material expenditures as well as effective net incomes are needed. The

effective net income is derived according to the following scheme:

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 11 -

Table 2: Calculation Scheme for Effective Income

Staff costs

-

Expenditures (taxes, insurance)

Total net income

-

Savings

-

Spending abroad

Effective net income

Source: SpEA, 2006.

From total staff costs, all expenditures which do not reach the employee (e.g. income tax) are

subtracted to give total net income. Savings are also subtracted from the total. Finally all

spending abroad is subtracted to give effective net income.

3.3.3 Calculation of the Employment Effects of Sport

Three different methods can be used in order to calculate the direct employment effects:

Method 1 uses the average personnel expenditure per year and per person to

calculate the effects.

Method 2 uses a common “employment structure” of the sector proportional to the

value-added.

Method 3 is based on labour productivity. The marginal labour productivity is defined

as the ratio of the change of productivity to the change of labour input (either number

of employees or working hours). The marginal labour productivity indicates the

change of productivity per additional employee. The inverse ratio, the so-called work-

coefficient, is a measure for the number of persons employed in the production

process.

For an extensive evaluation of the employment effects, further factors have to be considered.

For example, the occupation structure is an important issue. The occupation elasticity is

usually larger for workers than for employees, so that an expansion of the construction

activities will lead to a significant increase in the number of workers. A significant increase in

the number of employees is however not to be expected. Another important factor is the

extent of capacity utilization in the appropriate sectors. The full employment effect is only

realised at 100 per cent capacity utilization and an appropriate increase in the capacities due

to the projected extra demand. Beyond that, the tendency exists to compensate a non-

permanent demand by overtime and extra shifts rather than by an additional employment of

workers.

3.3.4 Calculation of Multiplier Effects

For each final expenditure multiplier effects are assumed, since each business needs

unfinished-goods as well as raw materials and supplies of other sectors for the production of

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 12 -

its products and/or services. Multipliers show how much of the production of other sectors is

needed to produce a certain good. For example, production of a sports car requires seats,

which come from a different sector. These seats again need textiles, thus affecting a third

sector and so on. The size of the multipliers primarily depends on the structure of the

“economic linkage” of the source sector to the remaining sectors. That means it depends on

how much is received from and delivered to all sectors directly as well as indirectly. The more

the sectors are interlinked, the higher are the multipliers, usually ranging from 1.0 to a little

more than 2.0. Applying multipliers on the direct effects generates the indirect effects. If for

example a football stadium costs 30 m Euro (direct effect) and construction sector reports a

multiplier of 1.8, the indirect effect will be (1.8 - 1.0) x 30, that is 24 m Euro.

It has to be considered that national businesses as well as foreign countries are involved in

the supply chain, but primary effects for a country depend only on import-adjusted values.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 13 -

4 Definition of Sport in the Economic Sense

The sport economy as a whole is not a separate statistically measured sector, but is part of

various other industries and economic sectors. National statistical offices measure sport

explicitly only by the category “operation of sports facilities” in NACE 92.6 where NACE

stands for “Nomenclature statistique des activités économiques dans la Communauté

européenne” and is a classification of industries according to their economic activity. Other

categories such as the production of sport articles, sport retail, and sport tourism are ignored

in the statistical definition.

From an economic point of view, sport is an activity which has repercussions in many

different areas of the economy. In Table 3 some important categories are listed as examples.

Table 3: Overview of some sport-related activities and products with economic impact

Consumer Expenditure

Goods and Services Conditional on Doing Sport

Veterinarian

Dietary Supplements

Sport Bets

Health

Services

Hotels, Restaurants

(sport tourism)

TV

Broadcasts

Doing Sport (According to the Statistical Definition)

Stadiums

Swimming Pools

Professional

sports

Goods and Services Necessary to Do Sport

Racing

Horses

Sport Shoes and

Clothes

Sport

Weapons

School

Education

Sport Cars,

Motorbikes

Fitness

Centres

Watches,

Clocks

Sailing Equipment

Dancing

Schools

Source: "Sport Satellite Accounts – A European Project: New Results" leaflet published by

the European Commission (April 2011).

The question arises as to how the economic importance of these sport-related activities can

be measured. For this purpose the EU Working Group "Sport & Economics" developed and

agreed upon the Vilnius Definition of sport.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 14 -

Economic

activities

Products Goods

World

level

ISIC CPC HS SITC

EU level NACE CPA PRODCOM CN

National

level

National

versions

of NACE

National

versions

of CPA

National

versions of

PRODCOM

Is the reference classification. Classifications are linked by the structure.

Is the reference classification. Classifications are linked by conversion tables.

Classifications are linked by conversion tables.

The Vilnius Definition of sport relates sport activities to specific industries, as they are

registered within the framework of the national accounts.

9

For most of our purposes the NACE categories are still too broad, because NACE refers to

specific companies (or production units); a better targeted measure is products instead of

production units called CPA. CPA is the abbreviation for “Classification of Products by

Activity” and is a classification of products. NACE and CPA are part of an international

classification system of industries and products. The relationship of these classifications is

clarified below.

10

Table 4: Scheme of Classifications

Source: replicated from circa.europa.eu: NACE revision 2.

The sport sector as such is not a NACE category, but NACE category 92.6 "Sporting

Activities" refers to a small part of the sport sector. This category includes sport facilities such

as stadiums, swimming pools, sport clubs and professional sport organisations. The EU

Working Group "Sport & Economics" has labelled this category "the statistical definition of

sport”. In Table 3 this is labelled ‘Doing Sport’. This can be considered to be the sport sector

from a traditional point of view. For example, in this statistical definition neither fitness

centres nor sport education are included.

9

The following text is derived from Meerwaarde Sports and Economics/Spea (2008).

10

The meaning of the other abbreviations fall outside the scope of this report, see:

http://circa.europa.eu/irc/dsis/nacecpacon/info/data/en/2007%20introduction.htm

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 15 -

Limiting sport to this NACE category is therefore quite arbitrary from an economic point of

view. Another, conceptually better, definition of the economic sport sector enlarges the

statistical definition of sport by all industries which produce goods that are necessary to

perform sport. Besides sport facilities, this classification includes, for example, manufacturing

of sport shoes and tennis rackets. The latter definition is referred to as the “narrow definition

of sport”. This definition is depicted in the lower part of Table 3.

In addition, the so-called “broad definition of sport” includes not only the statistical definition

and the narrow definition, but also those industries for which sport is an important input for

their production processes, e.g. television broadcasting or hotels accommodating guests

doing sport (sailors, skiers, hikers, etc.), as depicted in the upper part of Table 3.

Besides a list of all products which are considered to be sport-related, the Vilnius Definition of

sport includes several rules, which guide the classification and interpretation of sport

products.

Table 5: Vilnius Definition Set of Rules

1

Goods and services which are part of the statistical and narrow definitions of sport are

also part of the broader definition of sport. The broader definition of sport will be the

focus of the EU Working Group "Sport & Economics".

2

Multipurpose infrastructure and multipurpose durable goods which are not part of the

statistical definition of sport (NACE 92.6) will be excluded, e.g. roads, cars, TV sets,

play stations. Dedicated infrastructure (e.g. NACE 45.23.21/45.23.22) will be included.

3

To avoid double counting and to ensure comprehensiveness, correspondence will be

established between the manufacturing sections and the trade/retailing sections

(categories 51-52) of the table. Sections 51 and 52 are only relevant in terms of trade

margins.

4

Data will be collected on the basis of a common agreement on which NACE and CPA

categories to include. However, to take account of the country-specific sport landscape,

additional CPA categories may exceptionally be included over and above the basic list

agreed in the EU Working Group "Sport & Economics".

5

In general, only final expenditure (incl. capital expenditure) will be taken into account,

and not intermediate expenditure. Reference will be made to intermediate demand only

if it constitutes sizeable input for professional sport. In a similar way, industrial services,

where they are not sport-specific, will not be considered.

Source: Vilnius Definition of sport.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 16 -

The Vilnius Definition of sport is thus an overview of all product groups which are included in

the sport satellite account. It is not so much a definition of sport itself but a classification of

relevant product groups.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 17 -

5 Set up of a Multiregional Input-Output Table: Sport

The basic approach to calculating EU-wide economic effects of sport is to first enlarge the

national Input-Output Tables (IOT) by sport-related sectors. For this, all sport-content will be

extracted from the original sectors and form additional sectors. For example, sector 01,

agriculture, will be divided into “non-sport 01” (wheat, apples…) and “sport-related 01”

(racing horses, football lawn…). The sum of these new sectors must equal the original sector

01. Figure 1 and Figure 2 visualise this enlargement process.

These enlarged national IOTs will be called Input-Output Tables: Sport (IOTs:S). As these 27

IOTs:S are connected by intra-EU foreign trade, they can be linked together in a Multiregional

Input-Output Table: Sport (MRIOT:S) as depicted in Figure 7.

Calculating the links between the regions is a complex economic task for which several

methods were proposed. The three most important ones are:

The Interregional Input-Output Model (IRIO) by Isard (Isard (1953));

the Multiregional Input-Output Model (MRIO) by Chenery and Moses (Moses,1955);

the Balanced Regional Model by Leontief (Leontief,1963).

The major advantage of Isard’s model is that it is able to cover the whole variety of effects of

each sector and each region. This benefit however leads to the big disadvantage of the

model: the enormous effort of data collection. The number of input-output flows is determined

by (m×n)

2

with "m" being the number of regions and "n" the number of sectors. Even in a

small model with five regions and ten sectors, 2,500 data have to be determined. For Europe

an interregional Input-Output model would (as a minimum) cover 27 regions and 17 sectors,

that is (27×17)

2

or more than 210,000 data. As intended the study should not be based on

sectors but on the more detailed categories so that the amount of data necessarily increases

to (27×59)

2

or more than 2,500,000 data. With the sport-relevant extensions (sport satellite

account) of the national Input-Output Tables the interregional Input-Output Model would grow

to a (27×94)

2

matrix or around 6,400,000 data.

For this reason efforts have been made to develop multiregional models with less complexity,

like the one developed by Chenery and Moses. The MRIO, which has been steadily

improved and refined in the last 15 years, covers in its most detailed version for the United

States 51 regions and 79 sectors. Formally the MRIO resembles the model of Isard, but with

regard to the content it differs in that it implies a stability hypothesis. The table itself is set up

in two steps: as a first step the intraregional tables are created (one table for each region), in

a second step the import and export flows are collected.

The model is extendable to any number of regions and the big advantage is that the

complexity of the table stays much lower than in Isard’s model. The amount of data

necessary to fill the table is determined by n×m

2

+m×n

2

(n intermediate goods matrices being

m x m large plus import/export data for all m goods between the n x n countries). Thus the

example above (27 regions and 94 subsections) requires a little more than 300,000 data.

That is less than 5% of the data necessary in Isard’s model. Because of this simplification it

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 18 -

was decided to use the MRIO model of Chenery and Moses in the context of this study.

However it is not meant to be used for country comparison.

The structure of the Leontief model corresponds to the Isard model but the interpretation is

completely different and is more complicated, using different definitions of markets. Because

empirical tests showed that this model is only useable for a limited number of regions and

sectors and should not be used for longer periods (not longer than 3 or 5 years) it is not

applicable for this study and therefore will not be discussed in more detail.

5.1 National Input-Output Tables

The starting point for calculating the MRIOT:S is the collection of the 27 national IOTs which

serve as a basis for the 27 IOTs:S. Four of them were already available (Austria, Cyprus,

Poland, and UK) and after adapting they could be used in this study. For the remaining 23

countries, proxy-IOTs:S had to be computed. Technically speaking, these proxy-IOTs:S are

perfectly comparable to the four fully-fledged IOTs:S. The difference is in the economic

research performed to calculate them. National researchers focusing on their country alone

are supposed to have more time and better connections to key national data experts which

are particularly important for this type work. In contrast to this, computing proxy-IOTs:S is

comparable to running a remote analysis of a country’s economy. The result is good enough

for running EU-wide analyses, but should not be used on a single country basis. It is

therefore recommended that whenever a fully-fledged national IOT:S is finished by the

country’s experts, it should replace the proxy-IOT:S in the MRIOT:S.

Almost all EU-27 countries have an Input-Output Table or at least supply and use tables (see

below for the conversion process). The national IOTs correspond to Figure 1. The rows

correspond to the use of goods. Therefore one can read off the first row how much of Good 1

is used to produce Good 1, Good 2, and Good 3. This is the “intermediated use” of the good,

as it is used within the supply chains of the economy. Consumption of final goods are

reported the upper right quadrant. The table shows how much of Good 1 (and the other

goods below) is consumed by private households, the state, and how much is invested (or

put in stock etc.). The last possible use is exports. The sum of intermediate use, consumption

and exports equals total demand of a good. This is reported in the far right-hand column.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 19 -

Output Intermed. Goods

Consumption

Good 1

Good 2

Good 3

Private Consumption

Public Consumption

Investments

Exports

Good 1

Good 2

Good 3

Total

Taxes less subsidies

Total Interm. Consumpt.

Cons. fixed Cap.

Taxes

Wages

Profits

Gross Value Added

Production Value

Imports

Total Supply

Total Demand

Figure 1: Basic Input-Output Table for the EU-27

Source: SpEA, 2012.

The columns in the left part of the IOT refer to the production of the goods. Thus in the upper

part of the first column one can see how much of each good is necessary to produce Good 1.

After taxes are added and subsidies subtracted, total intermediate consumption can be read

off the table. These were the inputs to production. To transform these inputs into output,

capital is required. Gross value added (GVA) is the sum of all capital costs (machinery,

wages, profits, plus taxes). The sum of gross value added plus total intermediate

consumption equals domestic production (“production value”, PV) of Good 1. To find out how

much of each good is supplied and thus available in a country, add imports to domestic

production.

As each good which is produced has to be used in one way or another the entries in total

demand (right-most column) must be equal to those in total supply (lowest row).

For example, the Austrian Input-Output Table for 2005 shows that goods and services of CPA

01, “Products of agriculture, hunting and related services”, worth 6.395 bn Euro were

supplied and demanded. On the supply side,

domestic inputs worth 2.754 bn Euro were used (column-wise sum of the

intermediate goods matrix),

58 bn Euro taxes less subsidies were paid,

a gross value added of 1.927 bn Euro was achieved, and

further goods and services worth 1.657 bn Euro were imported.

The sum of the above values equals 6.395 bn Euro

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 20 -

Demand is split as follows:

4.171 bn Euro were used as inputs,

private consumption equalled 1.430 bn Euro,

other consumption (including public) 332 bn Euro, and

goods worth 462 bn Euro were exported.

The sum of these items also equals 6.395 bn Euro

In the next step, these IOTs have to be transformed into IOTs:S by splitting those sectors

which contain sport-related data into two parts. Therefore these sectors have to be identified.

Figure 2 shows the scheme of such an IOT:S. The shaded parts are sport-related, with the

dark shape of the intermediate goods matrix surrounding the non-sport part. Some see it as

“circling around” the non-sport part, thus calling it the “satellite account”.

According to the Vilnius Definition of sport the national Input-Output Tables are going to be

extended by the 35 sport-specific subsections. Therefore each good with sport-related

content is going to be split into a sport-related part (e.g. “15 S“ with “S“ being the sport

reference) and into a non-sport-related part (subsection total minus sport-related part). The

goods with sport-related content are: 01, 15, 17, 18, 19, 22, 23, 24, 25, 28, 29, 33, 34, 35,

36, 45, 50, 51, 52, 55, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 71, 73, 74, 75, 80, 85, 92, and 93. Some

CPA categories (e.g. CPA 02) do not contain sport and are left untouched. Thus there are in

principle three different types of categories: those which contain sport-related elements in the

original IOT, but appear in the IOT:S without these sport-related elements; those which never

contained sport-related elements; and the purely sport-related categories.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 21 -

Output Intermed. Goods Consumption

Good 1 N

Good 2 N

Good 3

Good 1 S

Good 2 S

Private Consumption

Public Consumption

Investments

Exports

Good 1 N

Good 2 N

Good 3

Good 1 S

Good 2 S

Total

Taxes less subsidies

Total Interm. Consumpt.

Cons. fixed Cap.

Taxes

Wages

Profits

Gross Value Added

Production Value

Imports

Total Supply

Total Demand

This IOT:S looks as follows (shadowed part of the table refers to the sport satellite account):

Figure 2: Extended Input-Output Table for the EU-27

Source: SpEA, 2011.

Table 6 shows the availability of Input-Output Tables at Eurostat for the purpose of the study

in the third column-triplet. As can be seen, most of the 27 EU Member States report Input-

Output Tables as well as import tables for the year 2005. Therefore this year was chosen as

the basis for our calculations. However, there are a few missing countries and Latvia has

Input-Output Tables for 1998 only. These earlier data can be updated using economic data of

2005. Adjustment took place through growth of gross production and gross value added by

leaving technical coefficients constant, which is a valid approach as these coefficients’

stability is empirically grounded and a centre piece of Leontief’s theory. Technology changes

occur much slower than changes in demand, thus the structure of the intermediate goods

matrix remains stable even over a time span of ten or more years. It is therefore possible to

update the last available Input-Output Table into a 2005 Input-Output Table.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 22 -

2005 2006 2007 2005 2006 2007 2005 2006 2007 2005 2006 2007

Austria √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Belgium √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Bulgaria √ √

Cyprus √ √ √ √ √ √

Czech Republic √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Denmark √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Estonia √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Finland √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

France √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Germany √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Greece √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Hungary √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Ireland √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Italy √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Latvia √ √

Lithuania √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Luxembourg √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Malta

Netherlands √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Poland √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Portugal √ √ √ √ √ √

Romania √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Slovakia √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Slovenia √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Spain √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Sweden √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

United Kingdom √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Use table

Supply table

Input-Output table

Table Imports

Country

1998

1998

2000/2001

2000/2001

Table 6: Availability of Input-Output and Supply and Use Tables

Source: Eurostat,

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/esa95_supply_use_input_tables/data/workbooks .

Retrieved: March 2012.

For Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Malta no Input-Output Tables are reported for any year. Although

database updates are frequent: between February 2011 and March 2012 several Input-

Output Tables for 2005 were added. However, the Input-Output Tables for Malta (see section

5.1.2), Cyprus, and Bulgaria had to be estimated for the purpose of the study.

11

These

estimated Input-Output Tables meet all methodological requirements of official ones.

However, national statistical institutions can collect more data, e.g. by interviewing

companies about their production technologies, and apply extensive plausibility checks with

their national experts, therefore differences certainly can occur if official IOTs are available for

comparison in the future.

11

Contacting the national statistic institutions resulted in additional useful information, but no IOTs were sent.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 23 -

x

x

x

x x x

x x

x

x x x

x x

x

x x

x x

x

S

Total supply at purchasers' prices

Domestic Supply

Valuation

Industries (NACE)

Products (CPA)

Imports

Margins

Taxes

S

Total supply at basic prices

Therefore estimated tables are used as substitutes only when no official national Input-

Output Table is available.

The IOTs of Denmark, the Netherlands, and Finland turned out to be a special problem as

they were only available as NACE x NACE tables. No CPA x CPA table could be obtained.

Since these were otherwise perfectly properly calculated IOTs, they were kept as they were,

since attempting to translate them to CPA x CPA tables (see chapter 5.1.1 below) would

probably destroy more information than it would create. Replacing them in future versions will

enhance the model’s precision for these countries.

5.1.1 Calculation of Input-Output Tables

As a few countries only reported supply and use tables (SUT) for 2005, the corresponding

Input-Output tables had to be derived from them. This section deals with this conversion.

5.1.1.1 Supply and Use Tables

Several of the following depictions and descriptions closely follow those in UK Office for

National Statistics (2002), Statistik Austria (2010), and Eurostat (2008).

Figure 3: Schematic Supply Table

Source: SpEA, 2011.

Supply Tables show the origin of goods and services in an economy. Figure 3 shows a

scheme of such a table which is composed of two separate parts. The matrix of domestic

supply can be found on the left side. It has product categories (e.g. CPA) in its rows and

industry categories (e.g. NACE) in its columns. In a row, call it i, one can thus read off all

industries which produce product i. For example, real estate services are CPA 70. They are

mainly supplied by real estate agents (industry NACE 70). However, there are also

construction companies (NACE 45) which sell the flats, offices, or swimming pools they

constructed. Product 70 is therefore produced by industry 70 and industry 45. Thus there can

be several entries in each row.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 24 -

x x

x x x x x

x x x

x x x

x x x x x

x x x

x x x x

x x x

x x x x x x

x x x x

x x x x x

x x x x x

Gross Value

added

Compensation of employees

Products (CPA)

Public consumption

S

Total Demand at purchasers' prices

Private consumption

Exports

Final Demand

Taxes less subsidies on production

Industries (NACE)

Gross operating surplus

S Production value at purchasers' prices

On the other hand, column j shows the goods and services produced by industry j. Using the

construction company in NACE 45 again, we see that it not only constructs swimming pools

but also sells them. Industry NACE 45 therefore produces goods of CPA 45 and CPA 70.

Therefore there can also be several entries in each column.

As there exists a close relationship between products and industries (construction companies

mainly construct buildings, selling them is only a side-business), the biggest values are

usually found in the diagonal. For Example, CPA 01 refers to “Products of agriculture, hunting

and related services” which are mainly produced in NACE 01 “Agriculture, hunting and

related service activities”. These are called “characteristic goods”, as it is an industry’s major

effort to produce them. However, there are many industries producing secondary or by-

products. One can imagine a farmer (NACE 01) who not only harvests grapes (CPA 01), but

also transforms them into wine (CPA 15), or a construction company (NACE 45) selling its

own buildings (CPA 70, real estate services). These are non-characteristic goods and

services and are depicted as the off-diagonal entries.

In addition to domestic supply of goods and services, imports are available too. The value of

each imported type of good is reported in a column-vector to the right of the Domestic Supply

or Make Matrix.

The sum (along row i) of domestic production and imports equals the total supply of product i

at basic prices. These are the prices which arise to the producer. To know the purchasers’

prices, one has to add margins and taxes.

Figure 4: Schematic Use Table

Source: SpEA, 2011.

Study on the Contribution of Sport to Economic Growth and Employment - 25 -

Use Tables, as depicted in Figure 4, again can be read row- and column-wise. Row i reports

the different usages of product i. If it is used for producing another good or service (an input

being transformed into another output), it is called an “intermediate good”. This “Use Matrix”

in the upper left corner of the Use Table again has products in rows and industries in its

columns. High values appear in the main diagonal, but inter-industry relations usually are

very pronounced leading to numerous large off-diagonal values too. For example, the 2005

UK Use Table reports products of CPA 01 worth 2.5 bn Euro flowing into NACE 01. However,

goods and services of CPA 01 worth 12.9 bn Euro are used in NACE 15 (Manufacture of

food products and beverages) as inputs.

On the right hand side the values of goods and services which are not used in the domestic

production process are displayed. These are in principal private consumption, public

consumption, and exports. These three categories (plus a number of others) are called “Final

Demand”. The sum of intermediate demand and final demand equals total demand for a

good, which is reported at purchasers’ prices.

Columns of Use Tables reveal the costs of inputs being used in an industry when producing

according to the Supply Table (thus including non-characteristic goods and services).

Intermediate goods and services needed in industry j are shown in the j-th column of the Use

Matrix. Taxes less subsidies can be interpreted as costs of public administration, providing all

the services of a modern state (roads, a legal framework, social security, education etc.).

Compensation of employees (wages), gross operating surplus (i.e. profits), and consumption

of fixed capital (depreciation) are three very important accounts as they specify the return on