U.S. Marine Corps

PCN 144 000339 00

MCRP 6-10.1

Spiritual Fitness Leader's Guide

Limited Dissemination Control: None

A non-cost copy of this document is available at:

https://www.marines.mil/News/Publications/MCPEL/

Report urgent changes, routine changes, and administrative discrepancies by letter or email to the

Doctrine Branch at:

Commanding General

United States Marine Corps

Training and Education Command

ATTN: Policy and Standards Division, Doctrine Branch (C 466)

2007 Elliot Road

Quantico, VA 22134-5010

or by email to: Doctrine @usmc.mil

Please include the following information in your correspondence:

Location of change, publication number and title, current page number, paragraph number,

and if applicable, line number.

Figure or table number (if applicable).

Nature of change.

Addition/deletion of text.

Proposed new text.

Copyright Information

This document is a work of the United States Government and the text is in the public domain in

the United States. Subject to the following stipulation, it may be distributed and copied:

Copyrights to graphics and rights to trademarks/Service marks included in this document are reserved

by original copyright or trademark/Service mark holders or their assignees, and are used here under a

license to the Government and/or other permission.

The use or appearance of United States Marine Corps publications on a non-Federal Government

website does not imply or constitute Marine Corps endorsement of the distribution service.

UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS

21 June 2023

FOREWORD

Marine Corps Reference Publication (MCRP) 6-10.1, Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide, is designed to

equip leaders with the information needed to understand and lead in spiritual fitness. This will enable

leaders to grow in their own spiritual fitness as well as to lead, teach, and facilitate periods of instruction,

professional military education, and professional spiritual fitness discussions.

This guide provides leaders with evidence-based information that outlines the benefits of spiritual fitness

both on an individual and unit level. While the word “spiritual” has historically been associated with

religion,

spiritual fitness takes a broader perspective and considers religious and non-religious beliefs,

principles, and values needed to persevere and prevail. This guide will help leaders understand and

communicate the cultural shift that has occurred that defines spirituality as encompassing non-religious and

religious belief systems, and that both are approaches to spiritual fitness. This publication complements

Marine Corps Tactical Publication (MCTP) 3-30D, Religious Ministry in the United States Marine Corps.

Reviewed and approved this date.

ERIC R. QUEHL

Colonel, U.S. Marine Corps

Director, Policy and Standards Division

Publication Control Number: 144 000339 00

Limited Dissemination Control: None

Table of Contents

Chapter 1. Spiritual Fitness: Precedence and Battlespace Significance

Definitions .................................................................................................................................. 1-1

Spiritual Readiness ............................................................................................................... 1-1

Spiritual Fitness .................................................................................................................... 1-1

Spirituality ............................................................................................................................ 1-1

The Priority of Spiritual Fitness .................................................................................................. 1-2

Commandant of the Marine Corps Guidance ............................................................................. 1-4

ALMAR 033/16 Spiritual Fitness ......................................................................................... 1-4

ALMAR 027/20 Resiliency and Spiritual Fitness ................................................................ 1-4

Spiritual Fitness in Marine Leader Development ....................................................................... 1-5

Spiritual Fitness in Warfighting .................................................................................................. 1-6

Chapter 2. Establishing a Spiritual Fitness Foundation

Tangible and Intangible Factors ................................................................................................. 2-1

Internal and External Influences ................................................................................................. 2-2

Three Elements to Spiritual Fitness ............................................................................................ 2-4

Personal Faith ....................................................................................................................... 2-4

Foundational Values ............................................................................................................. 2-6

Moral Living .......................................................................................................................... 2-7

Chapter 3. Self-Assessment

The Spiritual Fitness Self-Assessment Process .......................................................................... 3-1

Step 1: Know Your Influences .............................................................................................. 3-2

Step 2: Exercise Three Elements .......................................................................................... 3-2

Step 3: Evaluate Seven Indicators ........................................................................................ 3-2

Step 4: Determine Fitness Level ........................................................................................... 3-3

Chapter 4. Challenges and Resources

Correcting Common Misconceptions ......................................................................................... 4-1

Spiritual Fitness and Religion in Culture .............................................................................. 4-1

Spiritual Fitness is not the Sole Domain of the Chaplain ..................................................... 4-2

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

iv

Moral Injury ................................................................................................................................ 4-2

Seeking Help for Low Levels of Spiritual Fitness ...................................................................... 4-3

RACE Suicide Prevention .................................................................................................... 4-5

Suicide Warning Signs .......................................................................................................... 4-6

Suicide Prevention Resources ............................................................................................... 4-6

Chapter 5. Leadership Considerations

Using Stories to Lead Spiritual Fitness Discussions .................................................................. 5-1

How to Lead a Spiritual Fitness Discussion ............................................................................... 5-2

Preparation ............................................................................................................................ 5-2

Select Discussion Questions ................................................................................................. 5-2

Choose a Time and Location ................................................................................................ 5-2

Lead the Discussion .............................................................................................................. 5-3

Chapter 6. Integrations with Other Fitness Domains

Purpose of Integration ................................................................................................................. 6-1

Integration with the Physical Fitness Domain ............................................................................ 6-2

Integration with the Mental Fitness Domain .............................................................................. 6-3

Integration with the Social Fitness Domain ................................................................................ 6-5

Appendices

A. Stories that Illustrate Personal Faith

B. Stories that Illustrate Foundational Values

C. Stories that Illustrate Moral Living

D. Spiritual Fitness Guide Printout

E. Useful Website Links

Glossary

References and Related Publications

CHAPTER 1.

SPIRITUAL FITNESS:

P

RECEDENCE AND BATTLESPACE SIGNIFICANCE

DEFINITIONS

Spiritual fitness is a term used to describe a person’s overall spiritual health and reflects how

spirituality can help one cope with, enhance, and enjoy life. Spiritual readiness takes a macro

perspective that focuses on the institution. Spiritual fitness takes a micro perspective that focuses

on the individual Marine and Sailor. While there are many ways these terms can be defined, this

leader’s guide defines them as follows:

Spiritual Readiness

Spiritual readiness is the strength of spirit that enables the warfighter to accomplish the mission

with honor. Spiritual readiness is developed through the pursuit of meaning, purpose, values, and

sacrificial service. For many, it is inspired by their connection to the sacred and to a community

of faith (U.S. Navy, Chief of Chaplains Instructions 5351.1).

Spiritual Fitness

Spiritual fitness is the identification of personal faith, foundational values, and moral living from a

variety of sources and traditions that help Marines live out core values of honor, courage, and

commitment, live the warrior ethos, and exemplify the character expected of a United

States Marine.

Spirituality

Spirituality can be used to refer to that which gives meaning and purpose in life and can be

practiced through philosophy, religion, or way of living.

Non-religious expressions of spirituality include activities that seek to strengthen

commitment to family, love of life, and esprit de corps. Examples include, but are not

limited to, volunteerism, practicing gratitude, sharing kindness, serving others, and having

deep conversations. Religious expressions include activities that connect one to the Divine,

God, and the supernatural. Examples include, but are not limited to, prayer, meditation,

worship, spending time in nature, and participation in the sacraments. The spiritual fitness

of every Marine and Sailor is enhanced and promoted through activities that support one’s

personal faith, foundational values, and moral living.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

1-2

THE PRIORITY OF SPIRITUAL FITNESS

Marines develop strong mental, moral, spiritual, and ethical understanding because

they are as important as physical skills when operating in the violence of combat.

—Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication (MCDP) 7, Learning

Spiritual fitness is foundational to the making of Marines, sustaining the transformation, and

returning quality citizens to society

. It is an inextricable component of the DNA that makes a

Marine a Teufel Hunden, a Devil Dog. It is ultimately that invaluable component that integrates

and ties together the physical, mental, and social components of the human person in a holistic

way, the summation of which is much more powerful together than apart. Spiritual fitness

energizes a Marine holistically, leading to the creation of a tenacious, yet ethical warrior, who will

accomplish the mission with honor, but is more concerned for fellow Marines than him/herself.

This is a Marine who completes every combat task by applying the responsible use of force and

makes tough decisions under stress and pressure—characteristics critical in battlespaces today and

in the future. Such Marines maintain our esprit de corps by adhering to a higher standard of

personal conduct.

Leaders at all levels are responsible for preserving the physical, mental, spiritual, and social

fitness of the Marines and Sailors entrusted to their care. This responsibility applies to every link

in every chain of command from small-unit leaders to commanding officers. The Marine Corps’

success during times of competition and the conduct of war depends on leadership that balances

mission accomplishment and troop welfare. The small-unit leader is the key to building and

maintaining unit morale and efficiency. To maintain a high level of morale and efficiency in

combat, small-unit leaders must understand how to exercise and maintain their own spiritual

fitness while leading Marines and Sailors to do the same. While the word “spiritual” has

historically been associated with religion, spiritual fitness takes a broader perspective and

considers religious and non-religious beliefs, principles, and values needed to persevere and

prevail. Leaders will need to understand and communicate the cultural shift that has occurred

which defines spirituality encompassing non-religious and religious belief systems, and that both

are approaches to spiritual fitness.

Spiritual fitness is imperative for a Marine’s overall mental health. A May 2021 study published

by the Cost of War Project reported that since the events of 11 September 2001, the United States

has lost 7,057 Service members to war operations and an estimated 30,177 Service members and

veterans due to suicide. In other words, when compared to combat related deaths, suicide has

claimed the lives of four times more of our nation’s Service members. Deficiencies in spiritual

fitness are known contributors to the range of suicide risk factors. However, based on the available

evidence from public academic institutions and published science journals, being spiritually fit

(including religious involvement) translates to having fewer destructive behaviors. For example,

research shows that a person practicing individual spirituality is 62 percent less likely to die by

suicide, while those who practice spirituality within a faith community are 82 percent less likely to

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

1-3

die by suicide. Therefore, leaders must encourage Marines and Sailors to pursue spiritual fitness

and make use of the command religious programs (CRPs) at their discretion. Now more than ever,

the spiritual fitness of Marines and Sailors must be placed on the forefront of every leader’s mind.

Effective leaders take care of their Marines’ physical, mental, and spiritual needs. They also care

about the well-being and professional and personal development of their Marines. The leaders’

responsibilities extend to the families as well. Additionally, leaders must know their Marines:

where they are from, their upbringing, what is going on in their lives, and their goals, strengths,

a

nd weaknesses.

While Marines at every level are responsible for spiritual fitness leadership, small-unit leaders

must be equipped with the language and framework to articulate spiritual fitness elements and be

able to recognize when one of their Marines or Sailors is struggling. A decline in a Marine’s or

Sailor’s spiritual fitness has the potential to disable the most courageous Service member and

jeopardize mission accomplishment. General David H. Berger, 38th Commandant of the Marine

Corps, notes how critical Spiritual Fitness is to the character development of our Marines, and the

priority he attaches to its pursuit:

While the importance of physical, mental, and social fitness is more recognizable,

spiritual fitness is just as critical, and specifically addresses my priority to build character

and instill core values in every Marine and Sailor.

Research shows evidence that 18–24-year-olds experience a surge of spirituality, resulting in a

desire to explore the meaning and purpose of life and connect with the transcendent. Marines in

this age group comprise about 65 percent of the Marine Corps and are in a state of spiritual

formation where they may or may not choose to adhere to religious beliefs. This is the time when

they are asking questions that will form their worldview:

• What is the nature of reality?

• Are there transcendent beings such as God or other higher powers?

• What happens when I die?

• What is the meaning and purpose of life?

Young adults’ answers to these questions form a lens through which they view life events. Marine

leaders must understand this innate drive in their young Marines and seek ways to foster these

questions. Leaders can develop spiritual fitness by providing a safe, non-judgmental framework to

assist Marines and Sailors in asking and answering these questions. The CRP assists leaders to

facilitate spiritual exploration.

Investing in physical, mental, spiritual, and social health increases resiliency, the probability of

mission accomplishment, and operational success across the competition continuum. Just as

incorporating weightlifting sets and repetitions into one’s routine can make a person physically fit,

incorporating certain spiritual “sets and repetitions” into one’s routine can make a person

spirituality fit. This guide discusses some spiritual fitness practices that can be put into place.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

1-4

COMMANDANT OF THE MARINE CORPS GUIDANCE

ALMAR 033/16 Spiritual Fitness

On 3 October 2016, General Robert B. Neller, 37th Commandant of the Marine Corps, released

All Marines (ALMAR) message 033/16. This message emphasizes the need for every Marine and

Sailor to focus on all four domains of fitness for essential well-being, while highlighting the key

role of spiritual fitness. The message states, “By attending to spiritual fitness with the same rigor

given to physical, social and mental fitness, Marines and Sailors can become and remain the

honorable warriors and model citizens our Nation expects.”

ALMAR 027/20 Resiliency and Spiritual Fitness

On 20 December 2020, General David H. Berger, 38th Commandant of the Marine Corps,

released ALMAR 027/20. This message stressed the importance of all Marines and Sailors

optimizing their overall fitness to maintain the necessary toughness and resiliency needed for

mission accomplishment. The message states, “leaders must champion efforts to instill spiritual

fitness in order to advance character development across the Marine Corps and in support of my

Commandants Planning Guidance (CPG).” General Berger concluded that chaplains are uniquely

qualified to assist Marines in developing their spiritual fitness through religious ministry,

confidential counseling, and care for all individuals regardless of belief or background.

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

Leaders can use the following excerpts from ALMAR 033/16 and ALMAR 027/20 with

the accompanying discussion questions to facilitate dialogue on the importance of

spiritual fitness:

1. ALMAR 033/16 states, “Research indicates that spiritual fitness plays a key role in

resiliency, in our ability to grow, develop, recover, heal, and adapt.” How does one’s

spiritual fitness impact resiliency?

2. ALMAR 033/16 states, “By attending to spiritual fitness with the same rigor given

to physical, social and mental fitness, Marines and Sailors can become and remain

the honorable warriors and model citizens our Nation expects.” What are some

ways and means to attend to spiritual fitness with the same level of effort we give to

physical fitness?

3. ALMAR 027/20 states, “Character strengthens our collective warfighting spirit.

Clarity on core values optimizes our moral and ethical decision-making.” How does

both good and bad character impact our capability to fight?

4. ALMAR 027/20 states, “Together with the other domains of fitness, spiritual fitness

permits Marines and Sailors to draw upon collective spiritual resources in order to

maintain their resiliency and demonstrate their character.” What spiritual resources

have proven to be effective in yourself or successful Marines and Sailors you know?

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

1-5

SPIRITUAL FITNESS IN MARINE LEADER DEVELOPMENT

Leaders must ensure Marines are well-led and cared for physically, emotionally,

and spiritually, both in and out of combat.

—General David H. Berger

(38th Commandant’s Planning Guidance)

Marine Corps Order 1500.61, Marine Leader Development, is a comprehensive approach to

leadership development at all aspects of a Marine’s personal and professional life to sustain the

transformation instilled at entry-level training. Marine leader development provides a framework

to be used by Marines at all levels. This framework consists of six functional areas of leadership

development: fidelity, fighter, fitness, family, finances, and future. This publication addresses the

various aspects of fitness.

Fitness is a holistic approach to physical, mental, spiritual, and social balance. Well-rounded

Marines who address the spiritual, social, and mental aspects of fitness have more than just high

physical fitness and combat fitness test scores; their morale, cohesiveness, and resiliency are also

higher, helping them overcome the toughest challenges and facilitate a faster recovery. Marine

leaders who understand and exercise their spiritual fitness ensure the proper development of their

character which upholds and complements Marine leadership development and embodies the 15

leadership traits and 11 leadership principles.

Leadership Traits

• Bearing.

• Courage (both physical and moral).

• Decisiveness.

• Dependability.

• Empathy.

• Endurance.

• Enthusiasm.

• Initiative.

• Integrity.

• Judgment.

• Justice.

• Knowledge.

• Loyalty.

• Tact.

• Unselfishness.

Leadership Principles

• Know yourself and seek self-improvement.

• Be technically and tactically proficient.

• Develop a sense of responsibility among

your subordinates.

• Make sound and timely decisions.

• Set the example.

• Know your Marines and look out for

their welfare.

• Keep your Marines informed.

• Seek responsibility and take responsibility

for your actions.

• Ensure tasks are understood, supervised,

and accomplished.

• Train your Marines as a team.

• Employ your command in accordance with

its capabilities.

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

Leaders can visit the Marine Leader Development website (links to all websites are

listed in Appendix E) to become familiar with the available leader development

resources that cover the six functional areas of Marine leader development.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

1-6

SPIRITUAL FITNESS IN WARFIGHTING

One essential means to overcome friction is the will; we prevail over friction

through persistent strength of mind and spirit. While striving ourselves to

overcome the effects of friction, we must attempt at the same time to raise our

enemy’s friction to a level that weakens their ability to fight.

—MCDP 1, W

arfighting

Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1, Warfighting, provides the foundation for the relationship

between leadership and spiritual fitness. Military professionals are charged with the defense of the

nation; therefore, Marines must not only be experts in the art of war, but also individuals of action

and intellect, skilled at accomplishing all tasks. They are resolute and self-reliant in their

decisions, energetic and insistent in execution. Marine leaders have a tremendous responsibility;

the resources they will expend in war are human lives. Therefore, it is essential for leaders to

harness the intangible factors of combat to maximize total destructive force against the enemy.

MCDP 1 lists these intangible factors as morale, fighting spirit, perseverance, and effects of

leadership. Spiritual fitness would also be counted among these factors. The leader’s capability to

instill spiritual strength in the modern Marine and Sailor will serve to overcome friction, increase

lethality, and achieve combat victory.

General John A. Lejeune commented on the critical link between spiritual fitness and resiliency,

human performance, and combat effectiveness:

There is no substitute for the spiritual in war. Miracles must be wrought if victories are to be

won, and to work miracles men’s hearts must be afire with self-sacrificing love for each

other, for their units, for their division, and for their country. If each man knows that all the

officers and men in his division are animated with the same fiery zeal as he himself feels,

unquenchable courage and unconquerable determination crush out fear and death become

preferable to defeat dishonor. Fortunate indeed is the leader who commands such men, and it

is his most sacred duty to purify his own soul and to cast out from it all unworthy motives, for

men are quick to detect pretense or insincerity in the leaders, and worse than useless as a

leader is the man in whom they find evidences of hypocrisy or undue timidity, or whose acts

do not square with his word.

General Lejeune’s words articulate the affects a spiritually fit Marine or Sailor can have on

warfighting and mission accomplishment. There is a spiritual component to the conduct of war,

and the Marine or Sailor who is willing to engage in the intangible dimensions of humanity will be

the one who is able to demonstrate the spiritual dimension that General Lejeune describes as

having no substitute. Leaders who ensure the spiritual readiness of their Marines and Sailors for

the conduct of warfighting can better prepare them for the future operating environment.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

1-7

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

Leaders must become familiar with the myriad content available on the Marine Corps

Resilience website (links to all websites are listed in Appendix E). The site contains

information and resources on physical, mental, social, and spiritual fitness to assist

Marines and Sailors in the pursuit of total fitness. Some resources include the following:

• Marine Total Fitness Self-check Tool.

• Videos covering physical, mental, spiritual, and social fitness.

• Recommended reading lists.

• Discussion guides.

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

Leaders can use the following excerpts from MCDP 1 to facilitate discussions on

spiritual preparation for combat:

1. Friction (pages 1-5 and 1-6): “One essential means to overcome friction is the will;

we prevail over friction through persistent strength of mind and spirit.” Question:

What is meant by a strong spirit? Discuss the role of a strong spirit in the conduct of

war, as well as how to develop a strong spirit.

2. The human dimension (pages 1-12 and 1-13): “It is the human dimension which

infuses war with its intangible moral factors.” Discuss how a Marine or Sailor may

be impacted by the moral dimensions of war.

3. Physical, moral, and mental forces (pages 1-14 and 1-15): “War is characterized by

the interaction of physical, moral, and mental forces.” Discuss the mental and moral

issues a Marine or Sailor may encounter in war.

4. Combat power (page 2-18): combat power is made up of both tangible and intangible

elements. “Some may be wholly intangible such as morale, fighting spirit, persever-

ance, or the effects of leadership.” Discuss the intangible elements a Marine or Sailor

may experience in the conduct of war, and how each may impact an individual.

5. The conduct of war (page 4-7): “It requires a certain independence of mind, a

willingness to act with initiative and boldness, an exploitive mindset that takes full

advantage of every opportunity, and the moral courage to accept responsibility for

this type of behavior.” Discuss what moral courage is and why it is necessary in war.

CHAPTER 2.

ESTABLISHING A SPIRITUAL FITNESS FOUNDATION

TANGIBLE AND INTANGIBLE FACTORS

All of life is experienced through two factors. There are tangible (physical) factors and intangible

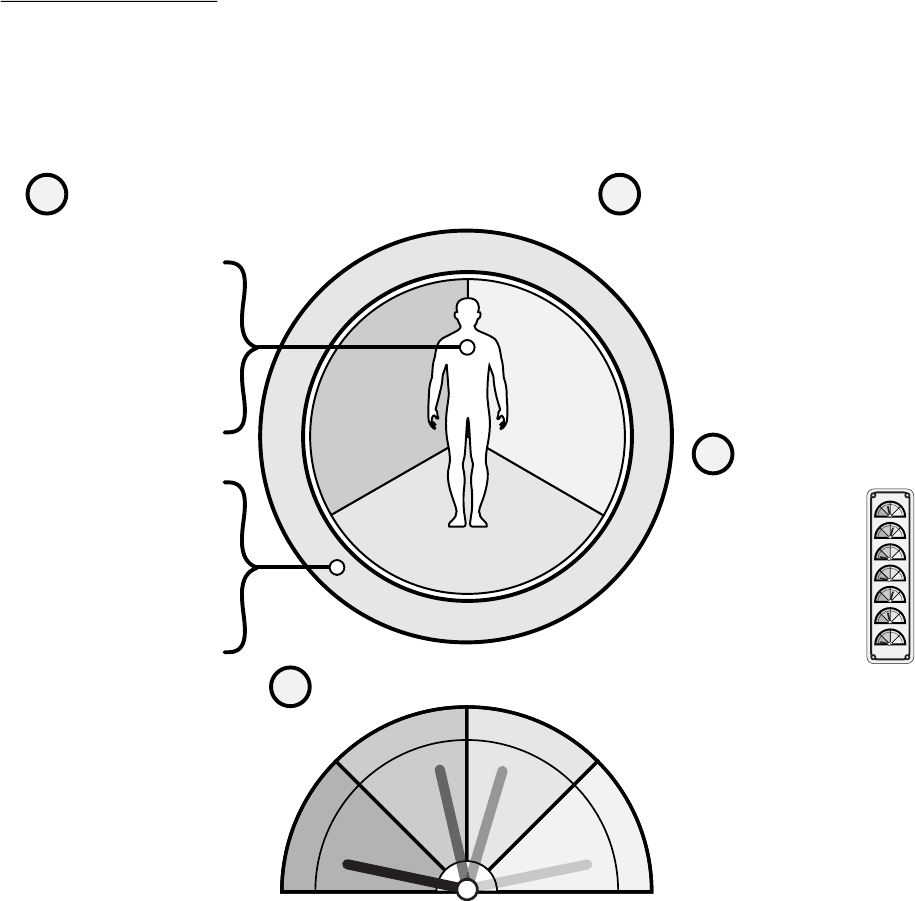

(non-physical) factors. As shown in Figure 2-1, intangible factors include matters that pertain to

the heart, mind, and spirit; these factors include such things as thoughts, ideas, emotions,

personality, behaviors, social skills, relationships, and spiritual connections. Tangible factors

include matters that pertain to our bodies and the environment and include our five senses. All

these factors interact with one another and impact one’s decisions and ability to persevere and

prevail in life. The Marine Corps values of honor, courage, and commitment are intangible

factors that are taught and expected of every Marine, regardless of duty status.

Figure 2-1. Tangible and Intangible Factors.

The spiritual fitness of a unit is most easily expressed in the term esprit de corps, which means

“spirit of the body

.” It has long defined the Marine Corps’ sense of camaraderie across the

battlespace. Esprit de corps describes the spirit of the unit, something intangible in nature but

experienced in very tangible ways. It is the common spirit reflected by all members of a unit,

providing group solidarity. It implies devotion and loyalty to the unit and all for which it stands, and

a deep regard for the unit's history, traditions, and honor. Esprit de corps is the unit's personality; it

expresses the unit's will to fight and win despite seemingly insurmountable odds. Esprit de corps

depends on the satisfaction the members get from belonging to a unit, their attitudes toward other

members of the unit and confidence in their leaders. True esprit de corps is based on the great

military virtues: unselfishness, self-discipline, duty, honor, patriotism, and courage.

Intangible

Tangible

Emotions

Behaviors

Social Skills

Relationships

Spiritual

Connections

Personality

Environment

See

Hear

Taste

Touch

Smell

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

2-2

INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL INFLUENCES

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred

battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will

also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb

in every battle.

—Sun Tzu

The Art of War

One of the principles of Marine leadership is to “know yourself and seek self-improvement.”

Every Service member enters the military with unique traits, perspectives, and experiences. The

first step Service members can take in knowing themselves and understanding their spiritual

fitness is to examine the influences that impact their daily decision making. These influences,

which can be internal or external, greatly shape how Marines and Sailors view the world and how

they make daily decisions, both personally and professionally. Figure 2-2 provides examples of

influences that can contribute to or detract from an individual’s spiritual strength and resilience.

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

Marines might remember being shown a series of benefit tags by their recruiter when

they were thinking about joining the Marine Corps and might be able to recall which

tags impacted their decision to stand on the yellow footprints. Each of these benefits can

be categorized as either a tangible or intangible benefit. Leaders can use this list of

benefits as a conversation starter with their Marines and Sailors to demonstrate the

tangible and intangible parts of our humanity:

• Pride of belonging.

• Self-reliance, self-direction, self-discipline.

• Travel and adventure.

• Challenge.

• Physical fitness.

• Courage, poise, self-confidence.

• Technical skills.

• Financial security, advancement, and benefits.

• Leadership and management skills.

• Professional development and opportunities.

• Educational opportunity.

• Patriotism.

• Pride and honor.

• Career variety.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

2-3

Figure 2-2. Internal and External Influences.

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

Leaders should take time to consider each of the internal and external influences,

annotating their impact on spiritual strength, resilience, and decision making.

Additionally, there can be influences not found on this list that should also be

explored. The better that leaders understand themselves and what impacts their daily

decision making, the better they will be prepared to articulate their own spiritual

fitness. How one personally answers the following questions will provide insight into

one’s foundational framework for interpreting information and experiences:

1. What is the nature of reality?

2. Are there transcendent beings such as God or other higher powers?

3. What happens when I die?

4. What is the meaning and purpose of life?

Leaders should consider how to offer opportunities for Marines and Sailors to conduct

this exercise. The command religious ministry team (RMT) can provide subject matter

expertise on exploring world-view questions and can offer related educational

opportunities for Service members and their families.

External Influences

Internal Influences

Cause of Purpose

Friends

Culture

Deity or deities

Family

Religion

Mentors

Philosophy

Leaders

Nation

Achievements

Abilities

Beliefs

Experiences

Personality

View Points

Goals

Talents

Education

Ambitions

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

2-4

THREE ELEMENTS TO SPIRITUAL FITNESS

The second step service members can take in understanding and living out their spiritual fitness is

deciding how they will maintain three elements of spiritual fitness (see Figure 2-3).

Figure 2-3. Three Elements to Spiritual Fitness.

Personal Faith

Personal faith is the belief or trust in oneself, something, or someone beyond oneself.

Semper Fidelis, the Latin phrase “Always Faithful,” is the motto of every Marine. It represents an

eternal and collective commitment to the success of our battles, the progress of our Nation, and a

steadfast loyalty to our fellow Marines. This motto was established in 1883 to distinguish the bond

developed and shared between Marines. It goes beyond words that are spoken; it is our warrior

ethos. Semper Fidelis is the fighting spirit of every Marine that animates the promise to win our

Nation's battles. We are always faithful to those on our left and right, from the fellow Marines we

fight alongside, to those in our communities we protect.

Every day, Marines and Sailors choose in whom or what they will place their faith and trust.

During entry-level training they are taught to place faith and trust in themselves, their fellow

Service members, the US Navy, US Marine Corps, or a higher power to accomplish the mission

with honor. They are given their first test to demonstrate faithfulness during the crucible exercise

at the Marine Corps recruit depots and battle stations at the Navy Recruit Training Command.

Each event places recruits in situations where they must put faith in themselves, the skills and

knowledge they have acquired, the training and education they have received, and their fellow

recruits to accomplish the mission.

Every Marine and Sailor benefits from taking time to recognize the unique beliefs, principles, and

values that help them persevere and prevail during difficulties. A good leader assists them along

this journey. When Service members place faith and trust in someone or something, experiences

Personal

Faith

Foundational

Values

Moral

Living

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

2-5

can vary. Sometimes they will experience reliability and trustworthiness that is reciprocated, and

other times they might encounter unfaithfulness, dishonesty, and betrayal. The latter can result in a

loss of faith, trust, and hope, which can lead to degradation of spiritual fitness or overall welfare.

As Marines and Sailors apply personal faith and experience to these events, they will view and

filter them through the myriad influences in Figure 2-2. How one responds to these events will

impact quality of life and spiritual fitness. Leaders must remain vigilant and alert to observe

personnel struggling with personal faith and take the time to provide a listening ear that

communicates to them that trustworthy leadership is available. Marines and Sailors need leaders

who embody Semper Fidelis to assist them in their lives and careers.

The concept of personal faith can be compared to rappelling. Just as rappelling requires a Marine

or Sailor to place faith in the rope and harness to make it safely to the bottom of a tower, life

requires them to place their personal faith in people and processes to accomplish the many tasks

and challenges they might face. Faith may be placed in oneself, personal skills and abilities, and

one’s intrinsic worth to overcome self-doubt and discouragement and improve performance. Faith

can be placed in family, friends, and other groups to create a sense of connection, purpose, and

support. Faith can be placed in our nation, the Navy and Marine Corps, or in a unit that creates

trust, connection, and teamwork. Faith can be placed in personal values and meaning that can have

a strong influence on the way one lives. Faith can be placed in a higher power or a divine presence

that may or may not be a part of a system of religious beliefs. These are just a few types of

personal faith that can be a part of a Marine’s or Sailor’s spiritual fitness. Leaders at every level

will need to be aware of what they choose to place faith and trust in and understand how that

choice gives greater connection, stability, and freedom in dealing with life’s challenges. It can be

helpful to describe positive life examples to be emulated as well as negative examples that

demonstrate resilience during adversity.

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

To lead Marines and Sailors in spiritual fitness conversations, leaders should find

stories of faith and trust, both good and bad. By using annotated examples of

faithfulness and unfaithfulness, leaders can better instill what it means to embody

Semper Fidelis.

• Look for stories that are applicable to spiritual fitness conversations on Semper

Fidelis and how it impacts mission accomplishment. Additionally, personal stories

can provide powerful examples.

• Compare the story to the list of influences in Figure 2-2, considering how much

faith and trust the main character places in each (small, moderate, great amount, or

none). These points will form the basis for the discussion.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

2-6

Foundational Values

Foundational values are the principles and standards that impact personal choices and actions,

thus influencing character displayed on and off duty.

The principles and values instilled in Marines and Sailors are the building blocks for making the

right decisions at the right time. In the chaos of war and the daily tasks of life, character matters.

The Navy’s and Marine Corps’ core values of honor, courage, and commitment define how all

Marines and Sailors are to think, act, and fight. General Carl Mundy, 30th Commandant of the

Marine Corps, defined the core values as:

HONOR: The bedrock of our character. The quality that guides Marines to exemplify the ultimate

in ethical and moral behavior; never to lie, cheat, or steal; to abide by an uncompromising code of

integrity; to respect human dignity; to have respect and concern for each other. The quality of

maturity, dedication, trust, and dependability that commits Marines to act responsibly; to be

accountable for actions; to fulfill obligations; and to hold others accountable for their actions.

COURAGE: The heart of our core values, courage is the mental, moral, and physical strength

ingrained in Marines to carry them through the challenges of combat and the mastery of fear; to do

what is right; to adhere to a higher standard of personal conduct; to lead by example, and to make

tough decisions under stress and pressure. It is the inner strength that enables a Marine to take that

extra step.

COMMITMENT: The spirit of determination and dedication within members of a force of arms

that leads to professionalism and mastery of the art of war. It leads to the highest order of

discipline for unit and self; it is the ingredient that enables 24-hour a day dedication to Corps and

Country; pride; concern for others; and an unrelenting determination to achieve a standard of

excellence in every endeavor. Commitment is the value that establishes the Marine as the warrior

and citizen others strive to emulate.

An essential aspect of spiritual fitness is acquiring values that will build character and resiliency.

Values are basic ideas about the worth or importance of people, concepts, or objects. Marines and

Sailors must determine the values that currently guide their life and adjust in pursuit of a

spiritually fit lifestyle. They gain insight by considering the internal and external influences that

are the sources of values. For example, a Marine who has a very close family (an external

influence), feels strongly connected to them (an internal influence), and values spending time with

them, will consider family when making choices on how to spend money and free time. When

critical decisions are being made, this Marine will often ask, “how will this decision impact my

ability to spend time with my family?” Individuals who take time to list what matters most gain

valuable insight into their pursuit of spiritual fitness.

The skill of land navigation provides an illustration for this spiritual fitness element. During land

navigation, Marines rely on the numerical values printed on the map and the compass. If any of

these numerical values are incorrect, they will soon find themselves off track. Similarly, Service

members can live by values that are not aligned with the core values of the Navy and Marine

Corps, which can lead them to violate the Uniform Code of Military Justice and take them off

track. Reflecting and taking time to ensure values are properly aligned is essential for

spiritual fitness.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

2-7

Moral Living

Moral living is making personal and professional decisions based on an internal or external

standard of what is right or wrong.

Marines and Sailors are taught moral decision making. At a minimum, their actions and behaviors

are governed by the Uniform Code of Military Justice, the oath of enlistment or oath of a

commissioned officer, code of conduct, and orders (external influences). These provide the

boundaries of what is acceptable. Leaders are taught to lead with higher standards of moral

responsibility and qualities (e.g., special trust and confidence, integrity, good manners, sound

judgment, discretion, duty relationships, social and business contacts).

Through exercising spiritual fitness, a Marine or Sailor can choose a moral standard of living that

meets, or even exceeds, the standards enforced within the Navy and Marine Corps. Moral living

standards can be derived from any one of the internal or external influences listed in Figure 2-2.

A Service member’s moral decision-making process can be positively or negatively affected by

organizations, governments, nationalities, family systems, religions, and philosophies.

To live morally, Marines and Sailors should first determine how they currently make moral

decisions. At times they will need to adjust that process to pursue a spiritually fit lifestyle. Once

they have determined their framework for moral decision making, they should look at the internal

and external influences that are the sources of their moral decision making.

General Charles Krulak wrote in his Commandant's statement on core values of United States

Marines that “character can be described as a ‘moral compass’ within oneself, that helps us make

right decisions even in the midst of shifting winds of adversity.”

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

Leaders should be able to list the foundational values they have chosen to live by and

tell the story of how those values have benefited both life and career. By doing so,

leaders can instill in the Marines and Sailors they lead the importance of evaluating

their own foundational values. To effectively articulate their spiritual fitness, leaders

should consider the following:

• From their list of foundational values, what motivations influence their decisions

and behaviors?

• What influences provide the source for their foundational values (review the list of

influences in Figure 2-2)? For example, the Marine Corps (an external influence)

teaches a leader the core values of honor, courage, and commitment, and the leader

has decided to live by these values.

• Recall times when it was necessary to remove a value because it was creating a

negative impact. This task includes recording personal stories of realigning values

to improve personal and professional success.

Leaders should use personal stories and experiences to demonstrate the importance of

foundational values and that show the importance of positive values in decision making

and mission accomplishment.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

2-8

As previously discussed, Marines follow a compass during land navigation; similarly, Marines

also follow a “moral compass” to live a moral life. Marines are taught to rely on a magnetic

compass to provide a constant orientation to magnetic north. With every turn or step, the

direction of north remains a constant and reliable data point that every navigational decision can

be based on. Without the compass, it is easy to get lost. Similarly, a Marine or Sailor can use

values, beliefs, conscience, and influences as a “compass” for making moral decisions. It is

critical that every Marine and Sailor takes the time to determine which influences comprise their

moral compass.

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

Leaders must take time to self-reflect and be able to articulate how they make and

evaluate moral decisions and what they use as a source for moral decisions.

Accomplishing this task prepares leaders to instill in their Marines and Sailors the

importance of evaluating their own method of moral living. Leaders can start by taking

the following steps:

• Examine the way they currently make and evaluate moral decisions, as well as the

source or moral compass that guides them. This task includes recording personal

stories of moral decision making with the use of a moral compass to lead spiritual

fitness conversations.

• Review the list of influences in Figure 2-2 to identify which items are sources for

their moral decision making.

• Identify the process they use to reflect upon and evaluate past decisions to inform

current and future decisions to learn from them and make better decisions in the

future. This task includes preparing to share the moral decision-making process

during spiritual fitness leadership conversations.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

2-9

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

One effective tool every Marine and Sailor can use to assess their moral decision-

making process is the observe, orient, decide, act (OODA) loop described in MCDP 1.

Though this tool was designed for combat operations, the OODA loop has been used

in business, law enforcement, management, education, and it can be applied to

spiritual fitness. Service members can consider using this process personally for moral

decision making. Consider the below OODA loop definitions, questions, and actions

to apply to moral decisions:

• Observe your situation by collecting new information.

Observe your past decisions and subsequent consequences and ask the following:

Was my decision morally right?

What were the consequences of my decision?

Am I happy with the decision that I made?

• Orient yourself by reflecting on the past.

Orient yourself to your biases, perceptions, and values. Ask the following:

What did I learn about myself, about people, and about life in general from the

decision that I made?

If I could do it all over again, would I make a different decision?

Would I adjust any of my morals, ethics, and beliefs?

• Decide what your next steps will be.

Decide what to do by considering your observations and orientation.

Remember: deciding is a continuous cycle of making the best judgment based on

what is known at that time.

• Act by following through.

Follow through on the decision while monitoring the outcome.

Remember: cycle back to orient when needed.

Remember: new information can affect the outcome.

Daily reflection on the decisions made; meeting with a leader, mentor, chaplain,

advisor, or friend for guidance and accountability; and setting goals for the future are

just a few ways Marines and Sailors can stay on their chosen moral paths.

CHAPTER 3.

SELF-ASSESSMENT

THE SPIRITUAL FITNESS SELF-ASSESSMENT PROCESS

As Marines and Sailors seek to gain a comprehensive understanding of their spiritual fitness, they

can use the four steps of the spiritual fitness self-assessment framework (see Figure 3-1).

Figure 3-1. Spiritual Fitness Self-Assessment Framework.

Respectful of others

Sound moral decisions

Hope for life/future

Life’s meaning/purpose

Able to forgive self & others

Engaged with family and friends

Engaged with core values and beliefs

External Influences

Internal Influences

Personal

Faith

Foundational

Values

Moral

Living

Abilities

Achievements

Ambitions

Beliefs

Education

Experiences

Goals

Personality

Talents

View Points

Cause of Purpose

Friends

Culture

Deity or deities

Family

Religion

Mentors

Philosophy

Leaders

Nation

Know your influences

1

Exercise three elements

2

Ɣ Personal Faith

ƔFoundational Values

ƔMoral Living

Evaluate seven

indicators

3

Determine your fitness level

4

G

r

e

e

n

Z

o

n

e

Y

e

l

l

o

w

Z

o

n

e

O

r

a

n

g

e

Z

o

n

e

R

e

d

Z

o

n

e

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

3-2

Step 1: Know Your Influences

Marines and Sailors will need to take time to list as many internal and external influences that

impact life, decision making, and resilience. The list a Service member develops will be dynamic,

growing and developing over time, and will serve to provide insight into one’s overall spiritual

fitness. Read How I got Here: Master Gunnery Sergeant [Lillian] McLaughlin (Appendix A).

Here is a short list of influences excerpted from the story:

• McLaughlin’s father was a Marine who inspired her to serve in the Marine Corps.

• She attended high school in El Paso, Texas, where she learned to love sports.

• She achieved a strong ability to place faith in her family and the Marine Corps.

• She achieved a strong desire to seek self-improvement, which resulted in a paralegal degree.

• She witnessed the 2001 terrorist attack on the Pentagon, which inspired her to love life.

Step 2: Exercise Three Elements

Marines and Sailors must take time to decide how they will regularly exercise the three elements

of spiritual fitness: personal faith, foundational values, and moral living. The following three

questions can be used to assess how one practically applies each element:

• Personal faith: In whom or what am I placing my faith or trust in? See Appendix A for

examples of personal faith.

• Foundational values: What are the values I currently live by? What do I value most? See

Appendix B for examples of foundational values.

• Moral living: What are the moral standards I use to guide my decision making? See Appendix

C for examples of moral living.

Step 3: Evaluate Seven Indicators

After a Marine or Sailor has completed steps one and two, he or she can move to step three,

which is to evaluate one’s level of spiritual fitness by reviewing seven potential indicators as

shown in Figures 3-2 and 3-3. Think of these seven indicators as potential warning lights on the

dashboard of a car. Depletion in one of these areas is a signal that attention might be required,

and help might be needed.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

3-3

Figure 3-2. Seven Indicators of Spiritual Fitness.

To begin step three, Marines and Sailors should access the Spiritual Fitness Guide found in

Appendix D, which is a full-sized, printable document for use within commands. With the guide

in hand, Service members will review the seven indicators that are categorized and described in

detail. Four fitness zones (green, yellow, orange, and red) are depicted that assist the reader in

selecting the description that best represents how they perceive themselves on each

indicator (see Figure 3-3).

Figure 3-3. Spiritual Fitness Guide.

Step 4: Determine Fitness Level

The fourth step in self-evaluating one’s spiritual fitness is selecting one of the four fitness zones

that most accurately describes one’s current state for each of the seven indicators (see Figure 3-4).

Life’s meaning/purpose

Hope for life/future

Sound moral decision-making

Engagement with family and friends

Ability to forgive self and others

Respectful of others

Engagement with core values and beliefs

Potential Indicators

Green Zone Yellow Zone Orange Zone Red Zone

Potential Indicators Potential Indicators Potential Indicators

Ɣ(QJDJHGLQOLIH¶VPHDQLQJSXUSRVH

Ɣ+RSHIXODERXWOLIHIXWXUH

Ɣ0DNHVVRXQGPRUDOGHFLVLRQV

Ɣ)XOO\HQJDJHGZLWKIDPLO\IULHQGV

DQGFRPPXQLW\

Ɣ$EOHWRIRUJLYHVHOIDQGRWKHUV

Ɣ5HVSHFWIXORIRWKHUV

Ɣ(QJDJHGLQFRUHYDOXHVEHOLHIV

Ɣ1HJOHFWLQJOLIH¶VPHDQLQJSXUSRVH

Ɣ/HVVKRSHIXODERXWOLIHIXWXUH

Ɣ0DNHVVRPHSRRUPRUDOGHFLVLRQV

Ɣ6RPHZKDWHQJDJHGZLWKIDPLO\

IULHQGVDQGFRPPXQLW\

Ɣ'LIILFXOW\IRUJLYLQJVHOIRURWKHUV

Ɣ/HVVUHVSHFWIXORIRWKHUV

Ɣ6WUD\LQJIURPFRUHYDOXHVEHOLHIV

Ɣ/RVLQJDVHQVHRIOLIH¶V

PHDQLQJSXUSRVH

Ɣ+ROGYHU\OLWWOHKRSHDERXW

OLIHIXWXUH

Ɣ0DNHVSRRUPRUDOGHFLVLRQV

URXWLQHO\

Ɣ:HDNO\HQJDJHGZLWKIDPLO\

IULHQGVDQGFRPPXQLW\

Ɣ1RWOLNHO\WRIRUJLYHVHOIRURWKHUV

Ɣ6WURQJGLVUHVSHFWIRURWKHUV

Ɣ'LVUHJDUGVFRUHYDOXHVEHOLHIV

Ɣ)HHOVOLNHOLIHKDVQR

PHDQLQJSXUSRVH

Ɣ+ROGVQRKRSHDERXWOLIHIXWXUH

Ɣ(QJDJHGLQH[WUHPHLPPRUDO

EHKDYLRU

Ɣ1RWHQJDJHGZLWKIDPLO\IULHQGV

DQGFRPPXQLW\

Ɣ)RUJLYHQHVVLVQRWDQRSWLRQ

Ɣ&RPSOHWHGLVUHVSHFWIRURWKHUV

Ɣ$EDQGRQHGFRUHYDOXHVEHOLHIV

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

3-4

Figure 3-4. Spiritual Fitness Zones.

A Service member with a strong spiritual foundation will generally remain in the green zone on all

seven indicators. However, everyone encounters hard and difficult seasons of life where they

might find themselves in the yellow zone. A strong spiritual core will enable the warrior to remain

resilient during those seasons and successfully recover after the stress has ended. Service

members who find themselves in the orange or red zones should immediately seek help. Chapter 4

discusses the challenges Marines and Sailors face and resources available for addressing and

developing their spiritual fitness.

Please note that Appendix D can be used as an abbreviated version of the self-assessment process.

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

Leaders should use the spiritual f

itness guide to assess their own level of spiritual

fitness to determine whether they are in the green, yellow, orange, or red zone for

each category. Once familiar, leaders should distribute this tool in digital or print

format to their Marines and Sailors and instill in them the importance of using this

tool on a regular basis. The command leadership will need to use the following

guidelines for implementation:

• Make the Spiritual Fitness Guide in Appendix D available to Marines and Sailors.

• The Spiritual Fitness Guide is for individual use to assist a Marine or Sailor to

know when it is time to seek help; it is not designed for the chain of command to

evaluate a Marine’s spiritual fitness or readiness.

• Commands seeking to employ the chaplain to implement a command-wide

spiritual fitness assessment to collect data and produce metrics regarding the

overall spiritual readiness of Marines and Sailors may consider using the

Consortium for Health and Military Performance (known as CHAMP). A link for

this website is listed in Appendix E.

• Commands should not mandate the use of the Spiritual Fitness Guide or require

Marines or Sailors to disclose self-assessment results.

• Commands should use RMTs to train Marines and Sailors on the use of this tool.

Religious ministry teams serve as the subject matter experts in the command regarding

individual or command-wide spiritual fitness matters and should be used to the fullest

extent possible.

G

r

e

e

n

Z

o

n

e

Y

e

l

l

o

w

Z

o

n

e

O

r

a

n

g

e

Z

o

n

e

R

e

d

Z

o

n

e

CHAPTER 4.

CHALLENGES AND RESOURCES

CORRECTING COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS

Spiritual Fitness and Religion in Culture

How an individual understands the terms spirituality and religion will impact their interaction

with both. Harold G. Koenig, M.D., Director of the Center for Spirituality, Theology and Health at

Duke University and lead author of the Handbook of Religion and Health, 3rd edition, is a

researcher who has authored more than 600 scientific peer-reviewed academic publications and

has contributed greatly to the science of religion and health. In 2008, Dr. Koenig explained how

the relationship between spirituality and religion has changed over the years. Historically,

spirituality was viewed as a subset of religion as depicted on the left side of Figure 4-1. This

historical framework categorizes religious personnel as spiritual and secular personnel as not.

However, the cultural understanding of spirituality has shifted to reflect the framework depicted

on the right side of Figure 4-1. The modern version of spirituality has expanded to view both

religious and secular personnel as having spirituality. For this reason, people might describe

themselves as spiritual but not religious. Leaders will need to be aware that Marines and Sailors

who view spirituality as a component of religion will most likely hear the word spiritual and

immediately equate that term to the topic of religion. During spiritual fitness dialogues, leaders

should review the cultural shift depicted in Figure 4-1 and be prepared to let their Marines and

Sailors know that, while religion is a common means by which to support spirituality, there are

also secular sources for spiritual development. No matter what avenue a Service member chooses

to pursue spiritual health, the desired end is to remain fit and in the green zone on all seven

indicators of spiritual fitness.

Figure 4-1. Spirituality Cultural Shift.

Spirituality

Religion

Secular

Cultural Shift

Spirituality

Secular

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

4-2

Spiritual Fitness is not the Sole Domain of the Chaplain

Marine Total Fitness was first introduced to the Marine Corps in 2011, encouraging every Marine

to exercise their physical, mental, spiritual, and social fitness. After more than a decade has

passed, every Marine is expected to develop the four domains of fitness as expressed by General

Berger in ALMAR 027/20 and defined in Marine Corps Order 1500.61. Religious ministry teams,

which consists of at least one chaplain and one religious program specialist, serve as subject

matter experts on the domain of spiritual fitness. The RMTs support the spiritual fitness needs of

Marines and their families by executing the core capability of care and by managing the CRP. As

established in Marine Corps Tactical Publication 3-30D, Religious Ministry in the United States

Marine Corps, chaplains deliver institutional care, counseling, and coaching that attends to

personal and relational needs outside of a faith group-specific context. Religious program

specialists are trained and positioned to support the delivery of care to individuals and

programmatically. Navy chaplains are assigned as special staff officers to assist commanders by

developing and implementing a CRP. Chaplains are the principal advisors to commanders for all

matters regarding the CRP within the command, to include religious and spiritual needs, morale,

morals, ethics, and well-being.

MORAL INJURY

Moral injury, while not a formal diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders (known as the DSM-V Manual), is widely accepted across multiple fields as a root

cause of stress and trauma symptoms. In simple terms, moral injury is a betrayal of what someone

believes is “right.” While research through the years has produced many definitions and

descriptions of moral injury (including those from philosophy, spirituality, healthcare, etc.), the

following two definitions of moral injury are studied in the military context, particularly among

Service members and veterans who have experienced combat:

• “Betrayal of what’s right, by someone who holds legitimate authority, in a high stakes

situation.”—Jonathan Shay, Achilles in Vietnam.

• “Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress

deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”—Brett Litz, William Nash, et al. Clinical

Psychology Review.

When moral injury has manifested, it presents symptoms like any stress-related or trauma-based

incident. However, typical approaches to addressing stress and trauma are often not effective

when moral injury is the cause of those symptoms. Moral injury can be caused when one

experiences betrayal by a person in authority, which may lead to loss of trust in that authority

figure. Moral injury can also be caused when one commits wrongdoing that may result in intense

feelings of guilt or shame for the moral violation, or when one violates moral and ethical norms.

These can lead to inner conflicts that require spiritual or soul repair. While moral injury might not

be completely understood, what is known is that those suffering from it who fail to address it can

experience difficulty coping with everyday life, withdrawal from social interaction, have

unhealthy relationships, and participate in risky or self-destructive behaviors. Moral injury

provides an opportunity to investigate multidisciplinary approaches that include spiritual, societal,

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

4-3

and psychological components. Service members suffering with moral injury should talk with

their chain of command or command chaplain for guidance to determine the most appropriate

resource. There are several methods to consider for addressing moral injury:

• Spiritual care and counseling.

• Psychotherapy.

• Use of rituals (secular or religious) to provide an avenue for healing, meaning, and pattern to

process difficult emotions and experiences.

• Use of writing to externalize and process traumatic experiences, control the level of

disclosure, and release painful memories.

• Use of meditation practices, music, and movement.

SEEKING HELP FOR LOW LEVELS OF SPIRITUAL FITNESS

A Service member lacking in spiritual fitness, as described by the orange or red zones of the

Spiritual Fitness Guide, might be experiencing inner conflict, loss of focus, mishaps, mission

failure, depression, anger, stress-related disorders, substance-use disorders, relationship

problems, violation of moral values, aggression, and suicidal thoughts. Inner conflict has been

found to be a key indicator for reduced spiritual fitness. Service members may experience high

levels of one or more of the following symptoms of inner conflict:

• Guilt.

• Shame.

• Feelings of betrayal.

• Moral concerns.

• Difficulty trusting others.

• Self-condemnation.

• Spiritual or religious struggles.

• Loss of meaning and purpose.

• Loss of religious faith.

• Difficulty forgiving and receiving forgiveness.

Spiritual injuries and struggles require spiritual interventions and solutions. Marines and Sailors

experiencing inner conflicts will be unable to find complete healing in medicine or behavioral

health alone. Service members seeking resolution and forgiveness for past wrongs or to renew

their connection to a higher power require spiritual assistance. Moral injury is an intangible

wound that has recently gained traction in the realm of psychology and now is a topic of much

study and development.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

4-4

Service members who identify themselves in the orange or red zone (see Figure 3-3) can take the

following actions and use the following resources as a road map to recovery:

• Seek help immediately. The orange and red spiritual fitness zones describe a mindset that has

little or none of each indicator for spiritual health. Now is the time to access the resources on

the Spiritual Fitness Guide and talk to someone.

• If thoughts of harming yourself or others are occurring, do the following:

Put personal safety first.

Do not keep negative and harmful thoughts to yourself.

Place distance between harmful thoughts and action.

Keep distance between yourself and lethal means (e.g., knives, guns, or medications) by

asking a loved one or trusted friend to remove them from your home.

Seek immediate help through one of the following resources:

Military Crisis Line:

Call 988 or 1-800-273-8255 and Press 1.

Chat online at MilitaryCrisisLine.net.

Send a text message to 838255.

In Korea and Japan: Call 0808 555 118 or DSN 118.

Military One Source counselors 1-800-342-9647.

Community counseling program (check local base listings).

Chaplain 100 percent confidential counseling (unit or base chapel).

Operational Stress Control and Readiness (known as OSCAR) team members.

Family, friends, mentors, leaders, and others you can trust.

Chain of command.

Medical.

• Seek long-term support. After seeking immediate help, long-term support is needed to assist

in the journey back to the green zone. This can be accomplished with resources that provide a

long-term relationship of assistance and accountability. There is no one-size-fits-all solution

as to which resource should be used or for how long. Much of this depends on discovering

what will work for the individual Marine or Sailor. Accountability and recovery groups can

be advantageous. Consider the following list for seeking long term support:

Chaplain 100 percent confidential counseling (unit or base chapel). Per Secretary of the

Navy Instruction 1730.11, Confidential Communications to Chaplains, chaplains are not

mandatory reporters.

Community counseling.

Mental health counseling and medication.

Medical.

Small-unit leadership and chain of command.

Recovery programs and accountability groups.

Religious community support programs.

Local civilian clergy.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

4-5

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resource

Leaders must be properly prepared to care for a Marine or Sailor who is showing signs

of depletion in spiritual fitness. Leaders can apply the mnemonic RACE when they

suspect one of their Marines and Sailors might be at risk of suicide.

RACE Suicide Prevention

Recognize distress in your Marine or Sailor:

• Note changes in personality, emotions, or behavior.

• Note withdrawal from co-workers, friends, and family.

• Note changes in eating and sleeping patterns.

Ask your Marine or Sailor:

• Calmly question about the distress you observed.

• If necessary, ask the question directly: “Are you thinking about killing yourself?”

Care for your Marine or Sailor:

• Actively listen, don’t judge.

• Peacefully control the situation; do not use force; keep everyone safe.

Escort your Marine or Sailor:

• Never leave your buddy alone.

• Escort to chain of command, chaplain, medical, or behavioral health professional.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

4-6

Spiritual Fitness Troop-Leading Resources

Suicide Warning Signs

Leaders should use the mnemonic IS PATH WARM to recognize suicide warning signs

in their Marines or Sailors.

Ideation: Thoughts of suicide expressed, threatened, written, or otherwise hinted at by

efforts to find means to suicide.

Substance abuse: Increased or excessive alcohol use or illegal drug use.

Purposelessness: Seeing no reason for living or having no sense of meaning or

purpose in life.

Anxiety: Feeling anxious, agitated, or unable to sleep (or sleeping all the time).

Trapped: Feeling trapped, like there is no way out.

Hopelessness: Feeling hopeless about self, others, or the future.

Withdrawal: Isolating and withdrawing from family, friends, usual activities, or society.

Anger: Feeling rage or uncontrolled anger, or seeking revenge for perceived wrongs.

Recklessness: Acting without regard for consequences, or engaging in excessively

risky behavior, seemingly without thinking.

Mood Changes: Experiencing dramatic changes

Suicide Prevention Resources

Links to websites with additional resources for suicide prevention are listed

in Appendix E.

CHAPTER 5.

LEADERSHIP CONSIDERATIONS

USING STORIES TO LEAD SPIRITUAL FITNESS DISCUSSIONS

Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 7 states that the Marine Corps’ learning philosophy “seeks to

create a culture of continuous learning and professional competence that yields adaptive leaders

capable of successfully conducting maneuver warfare in complex, uncertain, and chaotic

environments. Learning is developing knowledge, skills, and attitudes through study, experience,

or instruction. Learning includes both training and education.” Marines must develop the habit of

continuous learning early in their career. This publication also states, “Combat can challenge unit

cohesion and present Marines with a variety of moral and ethical dilemmas. Marines develop

strong mental, moral, spiritual, and ethical understanding because they are as important as

physical skills when operating in the violence of combat.” The Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

applies this learning philosophy through stories and practical application to talk about spiritual

readiness in a small-unit leadership format.

Leaders need to develop a framework for stories and illustrations to lead Marines and Sailors in

spiritual fitness conversations. Consider the following:

• Stories used in leadership conversations should be used solely to illustrate the principles of

spiritual fitness presented in this publication and engage learning on the topic of improving

spiritual fitness. They should not be used to instruct on a specific method of spirituality. As an

example, in the category of personal faith, a story may be used that tells of how Marines

adhered to a particular religion to improve their understanding of the meaning and purpose of

life, and how this resulted in green zone spiritual fitness. Stories such as these should not be

used to instruct Marines or Sailors that they have to be religious. Rather, the story is used to

illustrate how one individual exercised personal faith to strengthen his or her spiritual fitness.

It will be up to each individual Marine or Sailor to choose the source of their personal faith

and where they will place faith.

• The stories provided in this publication are meant to provide a “hip pocket” library of stories

to start conversations. Leaders can use these stories, and their own, to resonate with their

Marines and Sailors. Stories can be selected from books and articles, personal experiences, or

news stories. Stories selected for leadership conversations need to clearly depict:

How internal and external influences impact the subjects of the stories.

How the subjects of the stories exercised one or more of the three elements (personal faith,

foundational values, moral living), and how that exercise helped them preserve and prevail.

How the subjects of the stories might have scored themselves on any or all seven indicators

of spiritual fitness.

MCRP 6-10.1 Spiritual Fitness Leader’s Guide

5-2

HOW TO LEAD A SPIRITUAL FITNESS DISCUSSION

Leading Marines and Sailors in conversations and discussions on the topic of spiritual fitness

requires time to prepare and execute each period of learning. The following sections describe the

process leaders should use to implement the content in Appendices A through C of this publication.

Preparation

• Carefully select stories that will resonate with your Marines and Sailors and spark a good

conversation on the spiritual fitness topic being emphasized. Consider stories from a variety

of sources such as personal experiences, books, movies, television shows, and podcasts.

• Read the selected story and highlight examples that illustrate any part of the spiritual fitness

self-assessment (Figure 3-1). Use those examples to explain how the individual in the story

connects the dots of the framework of spiritual fitness. Ask the following questions to put

together notes for leading the conversation:

What influences (internal and external) are affecting subject of the story?

Which of the elements of spiritual fitness (personal faith, foundational values, moral living)

is the subject of the story exercising? How is that person exercising these elements?

How many of the seven indicators of spiritual fitness are in the life of the story’s subject?

How spiritually fit is the subject on the seven indicators of spiritual fitness?

Select Discussion Questions

• If leaders use the stories in this guide, they will need to read the discussion and reflection

questions and answer them from a personal perspective. If leaders use a story from another

selected source, they will need to develop questions for soliciting discussion among the

group, and another set of questions for personal reflection and consideration.