Andean Past Andean Past

Volume 13

Andean Past 13

Article 18

5-1-2022

Research Reports, Andean Past 13 Research Reports, Andean Past 13

David Chicoine

Louisiana State University

Beverly Clement

Louisiana State University

Linda S. Cummings

PalaeoResearch Institute

Victor F. Vasquez S.

ARQUEOBIOS

Teresa Rosales Tham

AQUEOBIOS, Trujillo, Peru

See next page for additional authors

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past

Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Chicoine, David; Clement, Beverly; Cummings, Linda S.; Vasquez S., Victor F.; Rosales Tham, Teresa;

Quave, Kylie E.; Heaney, Christopher; Hoffman, Alicia; Peck-Kris, Reed; and Ponte, Victor (2022) "Research

Reports, Andean Past 13,"

Andean Past

: Vol. 13, Article 18.

Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol13/iss1/18

This Research Reports is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more

information, please contact um.library.technical.ser[email protected].

Research Reports, Andean Past 13 Research Reports, Andean Past 13

Authors Authors

David Chicoine, Beverly Clement, Linda S. Cummings, Victor F. Vasquez S., Teresa Rosales Tham, Kylie E.

Quave, Christopher Heaney, Alicia Hoffman, Reed Peck-Kris, and Victor Ponte

This research reports is available in Andean Past: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol13/

iss1/18

RESEARCH REPORTS ON ANDEAN ARCHAEOLOGY

Plants and Diets in Early Horizon Peru:

Macrofloral Remains from Rehydrated Fecal

Samples at Caylán

David Chicoine (Louisiana State University,

[email protected]), Beverly Clement (Louisiana

State University, bevclement1015@gmail.com),

and Linda S. Cummings (PaleoResearch Insti-

tute, [email protected]

) report on the

macrofloral remains identified in nineteen

samples of dried feces recovered at the Early

Horizon center of Caylán (800–10 cal BC [2F]),

Nepeña Valley, coastal Peru. Results indicate

that maize, one of the most abundant plant

remains in Early Horizon deposits, is virtually

invisible at the macroscopic level in fecal sam-

ples, bringing insights into the ways maize was

processed and consumed (i.e., likely in the form

of beer and/or flour). Meanwhile, the ubiquity of

chili peppers, nightshades, and guava fruits

throughout the fecal corpus adds significant

information about the diversity of vegetal intake

by Early Horizon coastal populations. Indeed,

such plants are typically under-represented in

macrobotanic remains from archaeological

middens.

Beginning during the local Nepeña Phase

(800–450 cal BC) and reaching its apex during

the subsequent Samanco Phase (450–150 cal

BC), groups nucleated at the urban settlement

of Caylán while maintaining significant ties to

secondary rural and maritime communities who

supplied urban dwellers with cereals, fruits,

legumes, and seafood (Chicoine and Rojas 2013;

Helmer 2015). Carbohydrates appear to have

come mainly from the irrigation farming of

cultigens, smaller scale gardening of fruits, and

collecting wild plants (Chicoine et al. 2016).

The ubiquity of oversized vessels points to the

importance of feasting, especially fermenting

alcoholic beverages, in the maintenance of

authority (Chicoine 2011). Indeed, it appears

that, during the Nepeña Phase, malting tech-

niques related to the treatment of grains (i.e.,

maize) superseded fermenting starchy tubers

(i.e., manioc) (Ikehara et al. 2013). At Huam-

bacho, a small Early Horizon elite center located

eight kilometers southwest of Caylán, maize

remains count for more than sixty percent

(NISP [number of identified specimens]=265)

of the total plant remains (NISP=465). It is

significant that maize is both more labor inten-

sive and riskier than manioc. Indeed, the logis-

tics of maize beer production imply some level of

group coordination in order to manufacture

sufficient quantities for feasting (Jennings 2005).

This suggests that the intensification of maize

agriculture involved significant investments of

resources. Other edible plants documented in

Early Horizon deposits at Huambacho include

peanut, lima bean, avocado, pacay, squash, and

manioc (Chicoine 2011:449, Table 5).

Over the last three decades, research in the

Casma Valley, twenty kilometers south of

Nepeña, has yielded significant information to

reconstruct patterns of subsistence and human-

plant interactions during the Early Horizon.

Survey and excavation at the lower valley

settlements of San Diego and Pampa Rosario

have revealed the presence of several tubers

including potato, manioc, achira, and arrowroot

(Maranta arundinacea) (Pozorski and Pozorski

1987:51–70; Ugent et al. 1983). Other food

plants include chili pepper, lúcuma, and ciruela

de fraile (Bunchosia sp.). Both the Nepeña and

Casma botanical reconstructions are based on

A

NDEAN PAST 13 (2022): 445–455.

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022) - 446

macroremains from archaeological deposits,

typically middens, hearths, construction fills,

and floor scatters. The recent discovery of

expedient latrine contexts and dried feces at

Caylán allows for a more detailed consideration

of the plants processed and consumed during

the Early Horizon in coastal Ancash.

In 2009, Chicoine and Ikehara (2008[2010],

2014) initiated the first scientific excavations at

Caylán, confirming its central place in the

development of Early Horizon societies in

coastal Nepeña. The sampling of refuse deposits

and analyses of macrobotanic remains (e.g.,

seeds, stems, exocarps) have so far allowed the

identification of 35 plant taxa, 18 of which are

interpreted as edible. Taxonomic analysis of the

plant remains from Early Horizon deposits

allowed the identification of 4801 specimens,

2639 of which correspond to edible taxa (Table

1). Most food plants are cultigens including

maize (NISP=1310, 49.64 percent), peanut

(NISP=643, 24.37 percent), squash

(NISP=125, 4.74 percent), manioc (NISP=89,

3.37 percent), common bean (NISP=72, 2.73

percent), jack bean (NISP=27, 1.02 percent),

lima bean (NISP=26, 0.99 percent), achira

(NISP=15, 0.57 percent), chili pepper

(NISP=3, 0.11 percent), and sweet potato

(NISP=1, 0.04 percent). Wild or semi-wild

edibles are represented by a series of fruit trees

including avocado (NISP=199, 7.54 percent),

pacay (NISP=53, 2.01 percent), cansaboca

(NISP=26, 0.99 percent), lúcuma (NISP=22,

0.83 percent,) cherimoya (NISP=15, 0.53

percent), and guava (NISP=3, 0.11 percent), as

well as marine algae (Gymnogongrus furcellatus,

Ahnfeltia sp.) (NISP=2, 0.08 percent), and a

possible medicinal plant (palillo [Campomanesia

lineatifolia]) (NISP=9, 0.34 percent). While

several of these taxa are identifiable through the

macrofloral remains found in the rehydrated

fecal samples, the analysis points to significant

methodological implications, especially with

regards to the processing of certain crops.

PLANT TAXA NISP %

Maize (Zea mays) 1310 49.64

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea) 643 24.37

Avocado (Persea americana) 199 7.54

Squash (Cucurbita moschata) 125 4.74

Manioc (Manihot esculenta)893.37

Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris)722.73

Pacay (Inga feuillei)532.01

Jack bean (Canavalia sp.) 27 1.02

Lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus)260.99

Cansaboca (Bunchosia armeniaca)260.99

Lúcuma (Pouteria lucuma)220.83

Achira (Canna sp.)150.57

Cherimoya (Annona cherimola)140.53

Palillo (Campomanesia lineatifolia) 9 0.34

Chili pepper (Capsicum sp.) 3 0.11

Guava (Psidium guajava) 3 0.11

Marine algae (Gymnogongrus furcellatus, Ahnfeltia sp.) 2 0.08

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) 1 0.04

T

OTAL FOOD PLANTS 2639 100

Table 1. Edible plant taxa identified in the macro-

botanic remains excavated at Caylán (2009–

2010).

447 - Research Reports

Materials and Methods

Excavations at Caylán documented a total

of 58 features with fecal remains. Those are

associated with different contexts including a

monumental benched plaza (Plaza-A) (n=15),

a 10 meter high mound structure (Main

Mound) (n=13), a multi-functional residence

(Compound-E) (n=18), as well as streets

(n=4), an open public plaza (Plaza-C or Mayor)

(n=2), peripheral middens (n=2), and various

construction fills (n=4). After their in situ

identification and recording, the fecal remains

were collected, airbrushed, labeled, and bagged

in our field laboratory in Nepeña. Of those, 19

Fecal Samples (FSx) were selected for rehydra-

tion and transferred to the PaleoResearch

Institute in Golden, Colorado for a series of

detailed analyses including macrofloral, macro-

faunal, protein, starch, phytolith, and pollen.

The fecal samples analyzed shed light on deposi-

tion events associated with the Main Mound

(n=2 [FS105, 106]), the Plaza-A (n=6 [FS71,

77, 89, 101, 124, 125]), Compound-E (n=7

[FS94, 98, 108, 150, 151, 155, 173]), as well as

a street (n=1 [FS100]), construction fill (n=1

[FS148]) and peripheral midden areas (n=2

[S154, 159]) (Table 2). This report presents the

results of the macrofloral elements.

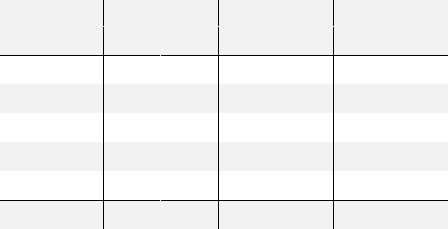

FECAL

SAMPLE

(FS)

U

NIT CONTEXT LEVEL WEIGHT

(DRY)

GRAMS

Mound A (UE4)

105 UE4-Ext2 Mound Summit 4 0.009

106 UE4-Ext2 Mound Summit 2 0.009

Plaza A (UE5)

71 UE5-Ext3 Corridor 3B 1 0.039

77 UE5-Ext4 Ramp 1 2 0.021

89 UE5-Ext3 Corridor 1B 1 0.017

101 UE5-Ext1 Platform 2A 3 0.021

124 UE5-Ext3 Corridor 1B 1 0.017

125 UE5-Ext3 Corridor 2-B2 3 0.008

Compound E (UE6)

94 UE6 Room 1 3 0.028

98 UE6 Room 1 2 0.020

108 UE6-Ext5 Room 4 1 0.019

150 UE6-Ext6 Room 4 3 0.020

151 UE6-Ext6 Room 4 3 0.005

155 UE6-Ext3 Room 5 2 0.010

173 UE6-Ext3 Room 5

Test Units (HP9, HP13, HP16)

100 HP9 3 0.019

148 HP13 1 0.007

154 HP16 1 0.025

159 HP16 1 0.021

Table 2. List of the fecal samples including their

provenance and weight.

The samples were rehydrated and processed

through standardized methods using a 0.5

percent aqueous solution of tri-sodium phos-

phate (Na

3

PO

4

) and reverse osmosis de-ionized

water. Approximately 75 percent of each fecal

sample was utilized. The remaining portion was

re-packaged and sealed for future analysis. The

hydrating samples were covered with plastic

wrap to prevent evaporation and contamina-

tion, and left to soak. The sample were soaked

between 24 and 42 hours, depending on differ-

ential rates of saturation. As the samples absorb

the tri-sodium phosphate solution, a color

pigment is revealed as a result of a chemical

process during solution absorption. Considered

an important feature when rehydrating human

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022) - 448

feces, the colors of the Na

3

PO

4

solution have

been used to differentiate between possible types

of depositors (e.g., humans, canines, felines). In

this report, suffice it to mention that both

chromatic and contextual evidence points to

the human origins of the coprolites. The stools

were typically lined up against wall lines, in a

manner consistent with human squatting. In

addition, contexts of deposit are closely related

to human activities, including renovation epi-

sodes, the abandonment of structures, and the

discarding of trash. Finally, their size and overall

content are highly consistent with human diets

and contrast with typical canine and feline

carnivorous diets.

Upon rehydration, each fecal sample was

removed from the solution and placed on a

piece of clean aluminum foil where it was cut

longitudinally. The two halves were laid open,

and measured quantities of fecal material were

removed from the inside of each stool in order

to recover pollen, phytolith, starch, and parasite

eggs. Four stools contained fragments of para-

sitic worms. The remainder of each sample was

then water-screened through 0.5 millimeter

mesh to recover macrofloral remains.

Preliminary results of the multiple proxy

lines confirm the importance of fish in Early

Horizon diets (Ková…ik et al. 2012). Traces of

fish remains are ubiquitous and found in 17 of

the 19 samples. Vertebrae, otoliths, and scales

of small fish were recovered, suggesting that

some fish were eaten whole. The presence of

marine diatoms, which are typically found on

the skin, gills, and in the stomachs of fish,

strengthen the hypothesis that small fish were

consumed whole. The ubiquity of sardines

(Sardinops sagax) across Caylán deposits further

supports this observation. The remainder of this

report focuses on macrofloral remains recovered

from the fecal samples.

Results

Taxonomic identifications of the macrofloral

remains recovered from the rehydrated fecal

samples are based on the recognition of epi-

dermises, seeds, foliage, stems, endosperms, exo-

carps, and perisperms. The elements identified

range in size from less than 0.5 to 1 millimeter.

The taxa identified and their ubiquity across the

19 samples provide significant insights into the

plants consumed at Caylán. The most ubiqui-

tous remains pertain to chili peppers (Capsicum

sp.), which are present in 13 of the 19 samples.

Other plants recognized in the samples include

squash (Cucurbita sp.) (n=1), beans (Phaseolus

sp.) (n=1), maize (Zea mays) (n=1), Malvaceae

fruit (n=2), Portulaca (n=1), guava (n=4),

datura (n=1), ground cherry/ tomatillo (Physalis

sp.) (n=4), amaranth (n=1), and unidentified

tuber epidermises (n=4). Flat sedge or nut seed

was found in one sample, but it is uncertain

whether this taxon constituted a significant food

source.

The samples originate from different con-

texts including (1) the Main Mound, currently

interpreted as a civic-administrative building;

(2) Plaza-A, a semi-public benched plaza nested

within a monumental residential compound

(Compound-A); (3) Compound-E, interpreted

as a neighborhood-based, supra-household living

and production area as well as; (4) street con-

texts, construction fills, and open air middens.

A comparison of the contents of the fecal sam-

ples with the associated macrobotanics brings

perspectives on the methodological implications

of both datasets. A total of 1404 NISP of edible

macrobotanics were recovered from the excava-

tion and test units where the feces were found

(Table 3). Those can be compared with the

presence/absence of the plant taxa identified

through the macrofloral remains found in the

coprolites (Table 4).

449 - Research Reports

Main Mound. FS105 and FS106 were depos-

ited during a renovation episode, and might

pertain to the residents of the area and/or the

builders. The stools were preserved by the rapid

covering of the fill layers by a plastered floor.

The two samples recovered in UE4 are striking

by their low plant richness, as only fragments of

unknown grassy plants were identified. The

absence of fruits, legumes, and other edible

vegetal foods common in fecal samples at Cay-

lán is puzzling. Only one other sample, from a

street context at HP9, displays similar results.

Plaza-A. Six samples were collected and chili

peppers are present in four of them. This is par-

ticularly significant because Capiscum remains

are rare (NISP=3) in the archaeological depos-

its at Caylán. Other taxa represented include

guava–also rare in the excavated refuse (NISP=

3)–as well as the common bean and Solanum,

likely tomato. It is significant that Solanum

remains are not visible in Early Horizon depos-

its. The relative richness of macrofloral remains

from UE5 may parallel a privileged access by

Compound-A residents and/or the special

function of the plaza (i.e., feasting). The macro-

botanics from UE5 confirm the richness of the

plant assemblages associated with the use of

Plaza-A. All plant taxa represented at Caylán

were documented in UE5, with the exception of

chili pepper, guava, and sweet potato.

TAXA (FOOD PLANTS)UE4

NISP

%

UE5

NISP %

UE6

NISP %

HP9

NISP %

HP13

NISP %

HP16

NISP %

T

OTAL

NISP %

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea) 370 52.41 96 30.87 19 13.10 13 61.90 11 5.50 509 36.25

Maize (Zea mays) 119 16.86 106 34.08 61 42.07 4 19.05 158 79.00 15 71.43 463 32.98

Avocado (Persea americana) 90 12.75 30 9.65 8 5.52 13 6.50 1 4.76 142 10.11

Squash (Cucurbita moschata) 18 2.55 28 9.00 37 25.52 4 19.05 12 6.00 99 7.05

Manioc (Manihot esculenta) 86 12.18 3 0.96 89 6.34

Common bean (Phaseolus

vulgaris)

28 9.00 2 1.38 6 3.00 4 19.05 40 2.85

Lúcuma (Pouteria lucuma) 4 0.57 3 0.96 10 6.90 17 1.21

Cansaboca (Bunchosia

armeniaca)

11 1.56 3 0.96 1 0.69 1 4.76 16 1.14

Pacay (Inga feuillei) 2 0.28 4 1.29 5 3.45 11 0.78

Lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) 1 0.14 4 1.29 2 1.38 7 0.50

Cherimoya (Annona cherimola) 5 1.61 50.36

Chili pepper (Capsicum sp.) 1 0.14 10.07

Guava (Psidium guajava) 3 0.42 30.21

Marine algae (Gymnogongrus

furcellatus, Ahnfeltia sp.)

10.32 10.07

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) 1 0.14 10.07

T

OTAL FOOD PLANTS 706 100 311 100 145 100 21 100 200 100 21 100 1404 100

Table 3. Relative frequencies of the plant taxa identified in the different excavated contexts corresponding

to the contexts in which fecal samples were collected.

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022) - 450

PLANT TAXA UE4

FS

UE5

FS

UE6

FS

HP9

FS

HP13

FS

HP16

FS

ABCDE FGH IJKLMNO P Q RS

Cucurbita

M

Phaseolus

M

Zea mays

M

Capsicum

MM MMMMMMMMM M MM

Malvaceae

MM

Portulaca

M

Psidium guajava

M M

Solanaceae

MMM

Datura-type

M

Physalis seed

MM

Solanum

MM

Amaranthaceae

Cyperus sp.

Unknown plant

MMMMMMMMM

Unknown tuber

epidermis

MM M M M

Key:

A FS105 K FS108

B FS106 L FS150

C FS71 M FS151

D FS77 N FS155

E FS89 O FS173

F FS101 P FS100

G FS124 Q FS148

H FS425 R FS154

I FS94 S FS159

J FS98

Table 4. Presence/absence of macrofloral remains from the rehydrated fecal samples from Caylán.

451 - Research Reports

Compound-E. UE6 excavations revealed

several rooms as part of a multi-functional

residential compound and fecal deposits are

associated with renovation episodes and the

abandonment of the place. The seven fecal

samples rehydrated from UE6 all contain chili

pepper. Unknown grassy plants are also ubiqui-

tous and found in four samples. One sample

(FS173) displays more richness and contained

maize, Solanaceae, ground cherry, and tuber

epidermis. FS173 is the only fecal sample at

Caylán to contain recognizable macrofloral

remains of maize. Macrobotanics from UE6

deposits, including the construction fill in Room

5, and floor scatters and hearths, are relatively

less rich than the assemblage from the Main

Mound and Plaza-A. The assemblage is limited

to maize, peanut, avocado, squash, common

bean, lúcuma, cansaboca, pacay, and lima bean.

Street. HP9 is associated with the end of a

street located in the northern portion of the

urban sector. A single fecal sample (FS100) was

found on the street surface. The stool was

collected from a layer associated with a floor

underneath a layer of windblown sand and dirt,

itself covered by the rubble of the collapsed

stone-and-mud wall of the street. The presence

of feces in HP9 suggests that streets at Caylán

were convenient places for defecating and

perhaps used as expedient latrines. It is also

possible that the street and surrounding neigh-

borhood was abandoned at the time of deposit.

Construction Fill. HP13 was placed at the base of

Cerro Cabeza de León in a small room pertain-

ing to Compound-N. The test unit sampled the

construction fill of a small bench. A single

sample (FS148) was collected from the bench

fill, itself composed of refuse and strata of reeds.

Our interpretation of the HP13 context exem-

plifies an expedient latrine, with fill materials

quickly covering the fecal deposits and helping

in their preservation. FS148 contains chili

pepper and a tuber epidermis showing similar

cell pattern to that of Calathea-type epidermis.

Macrobotanics recovered include peanut, maize,

avocado, squash, and common bean.

Midden Area. Two samples were collected

from HP16 (FS154 and 159) located at the base

of Cerro Caylán on the northwestern periphery

of the site. There are no obvious structures in

this area, which may represent an association of

an open-air, expedient latrine and a possible

midden refuse area. Our working hypothesis is

that most residents of the urban sector probably

used areas outside the dense, monumental core

to relieve themselves. Yet, those open air la-

trines would typically have a very low rate of

preservation due to natural weathering, and

scavenging animals. The stools recovered in

HP16 might have been buried by their deposi-

tors in association with the discard of trash.

The samples contain large quantities of

plant remains including traces of cucurbits.

Remains of chili pepper are represented in both

samples, as well as the only other trace of guava

fruit, unidentified nightshades (possibly toma-

tillo or ground cherry), unknown tuber epider-

mis (possibly achira or sweet potato), and rem-

nants of an unknown fruit from the Malvaceae

family. The variety in these two samples aligns

well with the samples found in UE5 and UE6.

The macrobotanics, in contrast, are less rich and

include maize, avocado, common bean, and

cansaboca.

In sum, this brief overview of the distribu-

tion of the fecal samples at Caylán contributes

to our understanding what the contents of

ancient human feces mean in relation to social

and economic factors. Yet, it is difficult to

correlate the location of defecation with actual

occupational phases. It is also difficult to link

the use of domestic space with specific defeca-

tion moments. UE5 corresponds to a restricted

space, where select individuals participated in

activities occurring at Plaza-A. Although the

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022) - 452

feces from UE5 show a variety of consumed

plants, they are unique in that they contain the

only identifiable remains of Solanum and almost

all evidence of guava (i.e., other evidence of

guava is in HP16).

Compound-E, is associated with residential

activities such as cooking, and other food prepa-

ration. Aside from FS173, all feces samples from

UE6 show a consistent diet primarily of fish and

chili pepper. Fecal material can represent food

consumed up to forty-eight hours (and longer)

prior to defecation, but the uniformity of the

samples from UE6 is significant. Considering the

amount of information provided by these nine-

teen fecal samples rehydrated from Caylán,

there is a considerable amount of evidence to

encourage further investigations into the rela-

tionship between Plaza-A and the residential

Compound-E. It can be hypothesized that the

apparent socioeconomic differences between the

people utilizing the space in Plaza-A, largely as

consumers, and those utilizing the space in

Compound-E, largely as food preparers, are

function based.

Discussion

All nineteen samples include at least one

part (seed, endosperm, glume, stem) of floral

remains in either a fragmentary or complete

identifiable state. Within the Solanaceae night-

shade family, chili pepper remains are present in

68 percent (n=13) of the samples and are in all

contexts of the site except for HP9 and UE4.

Nightshades including tomato (Solanum sect.

Lycopersicon) and tomatillo or ground cherry

(Physalis sp.) are present in 26 percent (n=5) of

the samples. Maize, tuberous cells, and fruits are

also present, albeit in lesser proportions overall.

In the fecal samples where chili pepper is

present, the remains are typically fragmented

and non-charred, except for the presence of a

single charred fragment in FS77 (UE5). The

tough seed coats of chili peppers can be broken

while chewing, preventing the seed from re-

maining intact through the human digestive

system. FS98 contained the highest count of

chili pepper seeds with 131 non-charred frag-

ments ($ 0.5 milimeters) and 30 chili seed

endosperms. Chili peppers are the only plant

remains recovered from all samples from UE6,

apart from FS173, while the non-floral frag-

ments are all marine or freshwater-based

foods–possibly indicative of preferred food

combinations within the residential areas of

Compound-E. Both food processing and chew-

ing might explain why most of the chili pepper

seeds are fragmented and not whole. The multi-

tude of ways that chili peppers can be processed

might account for the small amount of actual

intact seeds in the feces. Evidence for consum-

ing chili peppers is significant since traditional

macrobotanic retrieval techniques, including

screen size, used in conjunction with archaeo-

logical deposits, tend to underrepresent this

important plant.

Several nightshade family varieties are

represented including the tomato. Samples from

UE5 (FS101, 71), UE6 (173) and HP16 (FS154,

159) all contained evidence for plant taxa in the

Solanaceae family as either whole or fragmen-

tary non-charred pieces. FS71 from UE5 con-

tained the highest counts of non-charred to-

mato Solanum sect. Lycopersicon remains with

234 whole non-charred seeds, 70 non-charred

fragments ($1 millimeter), and 109 non-charred

seed fragments ($0.5 millimeter). Seeds less

than 0.5 millimeters were also present, but not

counted. In contrast to residing in the inner

cavity of the chili pepper, tomato seeds are

contained within a gelatinous membrane. This

structural element might account for the high

prevalence of whole tomato seeds compared to

any other plant seeds found in the feces samples.

Other notable plants common at Early

Horizon sites include tubers, fruits, and maize.

453 - Research Reports

The Caylán results indicate the presence of

these, albeit in smaller quantities and with more

limited spatial distribution. FS148 from HP13

yielded non-charred remains of Calathea-type

tuber/rhizome epidermis. The same tuberous

epidermis was found in FS101 and FS124 from

UE5, in FS150 from UE6, and in FS159 from

HP16. As suspected, fruits such as guava were

consumed at Caylán, but minimal amounts of

seeds and traces of endosperm were found in

FS77 from UE5 and FS159 from HP16, respec-

tively.

Among all of the edible plant remains found

in the feces at Caylán, maize was surprisingly

under-represented. This observation is signifi-

cant, considering the vast quantities of maize

cobs found in the macroscopic assemblage.

Maize appears only in FS173 from UE6 in the

form of glumes and kernel skins. The under-

representation of maize in the feces material

generates questions about the role of maize at

Caylán and the ways by which it was processed

and consumed. Maize is well represented in

refuse deposits, perhaps because cobs preserve

well in the arid environment. Simultaneously,

the evidence at Caylán suggests that maize is

being processed and consumed in a way that

would lessen its visibility in feces–such as being

consumed in beverage or flour form. Ongoing

analyses of starch grains from the Caylán copro-

lites should help clarify this issue, since the

processing of maize for chicha production can

alter their integrity (Vinton et al. 2009).

Data from HP16 generate questions about

the use of areas outside the urban sector for

defecation. FS154 and FS159 from HP16 con-

tained surprising plant richness. Most notable is

the large amount of non-charred cucurbit

(squash) exocarp and seed fragments in FS154.

This is the only sample to contain evidence for

consumed cucurbits. Cucurbits are more preva-

lent in the macrobotanical assemblage, but only

in the form of a few intact and fragmented

seeds.

Another significant line of evidence in the

feces samples is the presence of parasites. Para-

sitic evidence is found in more than 20 percent

of the fecal samples (FS71, 94, 155, and 150).

The samples come from Compound-E and

appear to be associated with diets consisting

mostly of fish and chili peppers. FS71 (Plaza-A,

UE5) shows the presence of a parasitic worm, as

well as jimsonweed (Solanaceae, Datura type),

which is a known psychotropic and medicinal

plant. At this point, the presence of parasites at

Caylán is preliminary and conclusions about

general health or access to medicinal aid due to

parasitic discomfort are unclear.

Concluding Remarks

The comparative study of macrobotanical

remains from feces and refuse deposits is valu-

able to understand human subsistence strate-

gies, food processing, and the taphonomy of

paleoethnobotanical remains. Indeed, the

analysis of gut contents from cess, stools, and/or

mummified intestines can shed light on varia-

tions in food preferences and combinations, as

well as cooking and other food processing meth-

ods. Fecal specialists have looked at pollen,

starch grains, protein residues, and phytoliths to

complement traditional emphases on macro-

botanical remains and other by-products typi-

cally found in refuse deposits (e.g., hearths,

discard piles, middens). Microscopic analyses

help discern whether plants, seeds, fruits, and

tubers were eaten young or mature, if grains

were pounded, broken apart, or eaten whole, or

even if roots and seeds were roasted before

consumption or preferred raw (Vinton et al.

2009). Furthermore, feces can present an encap-

sulated picture of relative health including

dietary deficiencies and exposure to parasites.

The results from our study suggest that maize is

well represented in archaeological deposits,

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022) - 454

while less visible in the macrofloral composition

of coprolites.

The results from our study suggest that

maize abundance in archaeological deposits

represents intense processing of an important

food item, whether ground or used in making

chicha. Insights from starch grains could further

support the importance of grinding of maize for

maize beer fermenting (Vinton et al. 2009).

Maize stands in stark contrast to chili peppers,

tubers, and some fruits which can be difficult to

identify in Early Horizon trash piles. Chili pep-

pers in particular are ubiquitous across the fecal

samples at Caylán.

The incorporation of feces is a critical addi-

tion to the analysis and interpretation of

paleodiets and available foods in Andean prehis-

tory. The ability to look beyond botanical re-

mains and incorporate feces data is valuable to

the fields of archaeology, paleoethnobotany, and

bioarchaeology. Expanding beyond traditional

approaches to understand prehistoric popula-

tions through architectural features, material

artifacts, and burial practices, feces reveal infor-

mation about food consumption habits. Few

archaeological remains other than feces reveal

individualist levels of history or specific human

events in time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Excavations at Caylán were made possible thanks to

the generous support of Louisiana State University’s

Office of Research and Economic Development and the

Department of Geography and Anthropology. Laboratory

analyses were funded by a grant from the Louisiana Board

of Regents (contract number LEQSF[2011– 2014]-RD-A-

05). Thanks go to the Ministerio de Cultura (formerly the

Instituto Nacional de Cultura) del Perú for considering

favorably the field project and permitting the exportation

of samples (804/INC-050609, 1230/INC-280510, 285-

2011-MC), as well as to Hugo Ikehara who co-directed

the excavations. Thanks also go to Ámparo Gomez, Kyle

Stich, Víctor Vásquez, and Teresa Rosales for their help

with the taxonomic identification of the botanical re-

mains.

R

EFERENCES CITED

Chicoine, David

2011 Feasting Landscapes and Political Economy at

the Early Horizon Center of Huambacho,

Nepeña Valley, Peru. Journal of Anthropological

Archaeology 30(3):432–453.

Chicoine, David, Beverly Clement, and Kyle Stich

2016 Macrobotanical Remains from the 2009 Season

at Caylán: Preliminary Insights into Early Hori-

zon Plant Use in the Nepeña Valley, North-

Central Coast of Peru. Andean Past 12:155–61.

Chicoine, David and Hugo Ikehara

2008 [2010] Nuevas evidencias sobre el Periodo

Formativo del valle de Nepeña: Resultados

preliminares de la primera temporada de

investigaciones en Caylán. Boletín de Arqueología

PUCP 12: 349–370.

2014 Ancient Urban Life at the Early Horizon Center

of Caylán, Peru. Journal of Field Archaeology

39(4):336–352.

Chicoine, David and Carol Rojas

2013 Shellfish Resources and Maritime Economy at

Caylán, Coastal Ancash, Peru. Journal of Island

and Coastal Archaeology 8(3):336–360.

Helmer, Matthew

2015 The Archaeology of an Ancient Seaside Town:

Performance and Community at Samanco, Nepeña

Valley, Peru (ca. 500–1 BC) BAR International

Series 2751. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Ikehara, Hugo, Fiorella Paipay, and Koichiro Shibata

2013 Feasting with Zea mays in the Middle and Late

Formative North Coast of Peru. Latin American

Antiquity 24(2):217–231.

Jennings, Justin

2005 La Chichera y el Patrón: Chicha and the

Energetics of Feasting in the Prehistoric Andes.

In: Foundations of Power in the Prehispanic Andes,

edited by Kevin J. Vaughn, Denis Ogburn, and

Christina A. Conlee, pp. 241–259. Archaeological

Papers of the American Anthropological Association

14. Berkeley, California: University of California

Press.

Ková…ik, Peter, Kathryn Puseman, Chad Yost, Melissa K.

Logan, Linda S. Cummings, Beverly Clement, and David

Chicoine

2012 Multiproxy Analysis of Coprolites from the Early

Horizon Center of Caylán (800–1 BCE), Coast of

Northern Peru. Paper presented at the 35th

Annual Meeting of the Society of Ethnobiology,

Denver, Colorado, April 11–14.

Pozorski, Shelia and Thomas Pozorski

1987 Early Settlement and Subsistence in the Casma

Valley, Peru. Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa

Press.

455 - Research Reports

Ugent, Donald, Shelia Pozorski, and Thomas Pozorski

1983 Restos arqueológicos de tubérculos de papas y

camotes del Valle de Casma en el Perú. Boletín de

Lima 25:1–17.

Vinton, Sheila Dorsey, Linda Perry, Karl J. Reinhard,

Calogero M. Santoro, and Isabel Teixeira-Santos

2009 Impact of Empire Expansion on Household Diet:

The Inka in Northern Chile’s Atacama Desert.

PLOS ONE 4(11):e8069.

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022) - 456

Taxonomic Analyses of the Vertebrate Fau-

nal Remains from Caylán, Peru

David Chicoine (Louisisiana State Univer-

(ARQUEOBIOS, vivasa2401@yahoo.com) and

Teresa Rosales (ARQUEOBIOS,

[email protected]) report on the analy-

sis of the vertebrate faunal remains from the

Early Horizon center of Caylán, Nepeña Valley,

coastal Ancash, Peru. Excavations in 2009 and

2010 have yielded some 10 kilograms of verte-

brate remains. A total of 3289 Number of Iden-

tified Specimens (NISP) were identified, classi-

fied, and quantified. Results indicate that Cay-

lán dwellers relied on a variety of fish, birds, and

mammals. Mammal domesticates are repre-

sented by camelids, dogs, and guinea pigs. Wild

mammals such as deer and sea lions appear in

lesser proportions. Marine resources occupied a

predominant place as suggested by the richness

and diversity of the fish assemblage. Most fish

were caught from the shore, likely from the

nearby sandy beaches located some fifteen

kilometers from Caylán. Yet, the existence of

fishing satellites nearer to the shore, combined

with the nature of the Caylán archaeological

assemblage, suggest the existence of exchange

networks in which marine products, mostly fish

and shellfish, traveled. Wild birds were caught

in surrounding marshlands through opportunis-

tic hunting, and appear to have been less impor-

tant in urban diets.

The Caylán research indicates that the

origins of urban life ways in coastal Ancash

increased the reliance on animal domesticates

for food, transportation, bones, and fibers. Yet,

wild animals continued to play a major and

dynamic role in subsistence activities, especially

fish and shellfishing. Intrasite analyses of species

and anatomical distributions confirm widespread

exploitation of identified taxa, yet little evi-

dence exists for significant differences in access

to potentially more prized animal products.

Caylán is a large multi-component archaeo-

logical complex with rich Early Horizon deposits

dated between 800 and 10 cal BC (2F). Results

of the excavations, as well as various specialized

analyses, have been presented elsewhere

(Chicoine and Ikehara 2014; Chicoine et al.

2016; Chicoine and Rojas 2013). In this report,

we focus on the zooarchaeological analysis of

the macrofaunal remains of vertebrates. All

excavated materials were screened using a three

millimeter mesh. Recovery efforts targeted one

hundred percent of the screened remains which

were transferred to the Centro de Investiga-

ciones Arqueobiológicas y Paleoecológicas

Andinas (ARQUEOBIOS).

Osteoarchaeological analyses focused on

unworked bone remains and are believed to

represent patterns of subsistence, in particular

the acquisition, processing, and discard of meat.

Taxonomic identifications were realized using

reference collections and published literature for

comparisons of each taxon. ARQUEOBIOS

houses the most comprehensive reference

collection for the zooarchaeology of the north

coast of Peru. Numbers of Identified Specimen

(NISP) were preferred over weight and Minimal

Number of Individuals (MNI). NISP values

were calculated based on the number of ana-

tomical parts specific to each species analyzed.

Osteometric values were also calculated for

camelid remains based on published literature to

distinguish between the different taxa. Camelid

osteometry focused on the first phalanges of the

anterior and posterior limbs. Meanwhile, tapho-

nomic observations emphasized cut, breakage,

and other marks indicating butchering and

other processing practices.

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022):456–462.

457 - Research Reports

Taxa Mound-A

(UE1, 4)

Plaza-A

(UE2, 5)

Compound-E

(UE6)

Others

(UE3, HPs)

TOTAL

NISP % NISP % NISP % NISP % NISP %

Amphibians/Reptiles

Bufo sp. 7 0.8 1 0.1 8 0.24

Unknown amphibian 6 0.8 59 6.3 65 1.98

Unknown reptile 9 1.1 20 2.1 29 0.88

Fish

Mustelus sp. 1 0.1 1 0.1 2 0.06

Carcharhinus sp. 1 0.1 2 0.3 3 0.09

Sphyrna sp. 2 0.2 2 0.3 1 0.1 1 0.1 6 0.18

Rhinobatos planiceps 1 0.1 10 1.3 11 0.33

Rajidae 1 0.1 1 0.03

Myliobatis sp. 6 0.7 7 0.9 2 0.2 3 0.4 18 0.55

Galeichthys peruvianus 6 0.6 4 0.5 10 0.30

Muraenidae 1 0.1 1 0.03

Engraulis ringens 32 4.2 32 0.97

Ethmidium maculatum 20.3 10.13 0.09

Sardinops sagax 50 6.0 92 12.0 137 14.5 99 13.3 378 11.49

Mugil cephalus 5 0.6 4 0.4 18 2.4 27 0.82

Labrisomus philippii 30.43 0.09

Trachurus symmetricus 3 0.4 13 1.7 6 0.8 22 0.67

Trachinotus sp. 3 0.4 3 0.09

Paralonchurus peruanus 3 0.4 1 0.1 6 0.6 4 0.5 14 0.43

Paralonchurus sp. 2 0.2 1 0.1 1 0.1 1 0.1 5 0.15

Stellifer minor 18 2.1 6 0.8 2 0.3 26 0.79

Cynoscion sp. 37 4.4 10 1.3 16 1.7 34 4.6 97 2.95

Sciaena deliciosa 1 0.1 1 0.1 54 7.3 56 1.70

Sciaena starksi 3 0.4 1 0.1 4 0.12

Sciaena gilberti 20.2 2 0.06

Sciaena sp. 5 0.6 16 2.1 21 2.2 15 2.0 57 1.73

Larimus sp. 8 1.0 6 0.8 43 4.6 12 1.6 69 2.10

Micropogonias altipinnis 16 1.9 1 0.1 7 0.7 7 0.9 31 0.94

Pareques sp. 23 3.1 23 0.70

Menticirrhus sp. 1 0.1 1 0.03

Calamus sp. 1 0.1 1 0.1 2 0.06

Caulolatilus sp. 2 0.3 2 0.06

Serranidae 1 0.1 1 0.03

Paralabrax sp. 17 2.0 14 1.8 5 0.5 8 1.1 44 1.34

Acanthistius sp. 1 0.1 1 0.03

Anisotremus scapularis 57 6.8 9 1.2 24 2.5 13 1.8 103 3.13

Merluccius gayi 20.2 2 0.06

Scomber sp. 4 0.5 4 0.4 1 0.1 9 0.27

Sarda chilensis 2 0.2 1 0.1 1 0.1 16 2.2 20 0.61

Unknown fish 37 4.4 16 2.1 50 5.3 26 3.5 129 3.92

Birds

Diomedea sp. 1 0.1 1 0.03

Phalacrocorax bougain-

villii

8 1.0 5 0.7 1 0.1 13 1.8 27 0.82

Larus sp. 15 1.8 1 0.1 9 1.0 1 0.1 26 0.79

Laridae 2 0.2 2 0.3 4 0.12

Puffinus sp. 20.32 0.06

Scolopacidae 10.1 1 0.03

Charadridae 2 0.3 2 0.06

Egretta sp. 10.1 1 0.03

Gallinula chloropus 10.1 1 0.03

Anas sp. 1 0.1 11 1.4 12 0.36

Zenaida asiatica 12 1.4 35 4.6 14 1.5 13 1.8 74 2.25

Zenaidura sp. 10.1 20.220.35 0.15

Columbina sp. 1 0.1 4 0.5 5 0.15

Strigidae cf Asio sp. 10.11 0.03

Vultur gryphus 10.1 1 0.03

Coragyps atratus 11 1.2 11 0.33

Hirundo sp. 1 0.1 44 5.9 45 1.37

Bartramia sp. 1 0.1 1 0.03

Sturnella sp. 8 1.0 2 0.2 1 0.1 11 0.33

Icteridae 1 0.1 1 0.03

Unknown bird 12 1.4 18 2.4 26 2.8 20 2.7 76 2.31

/...Continued on following page

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022) - 458

/Continued from preceding page

Taxa Mound-A

(UE1, 4)

Plaza-A

(UE2, 5)

Compound-E

(UE6)

Others

(UE3, HPs)

TOTAL

NISP % NISP % NISP % NISP % NISP %

Mammals

Muridae 111 13.2 216 28.3 77 8.2 89 12.0 493 14.99

Cavia porcellus 73 8.7 63 8.2 42 4.5 57 7.7 235 7.15

Lagidium peruanum 10 1.2 6 0.8 3 0.3 1 0.1 20 0.61

Canis familiaris 46 5.5 46 6.0 144 15.3 27 3.6 263 8.00

Felis sp. 4 0.5 2 0.2 6 0.18

Unknown carnivore 6 0.7 2 0.3 8 0.24

Otaria sp. 1 0.1 7 0.7 7 0.9 15 0.46

Odocoileus virginianus 10.1 30.44 0.12

Lama sp. 164 19.5 72 9.4 151 16.0 50 6.7 437 13.29

Unknown mammal 63 7.5 37 4.8 39 4.1 41 5.5 180 5.47

TOTAL 840 100.0 764 100.0 943 100.0 742 100 3289 100.00

Table 1. Total vertebrate remains analyzed from Caylán.

Vertebrate Taxa at Caylán

Taxonomic analyses allowed the identifica-

tion of 3289 NISP (Table 1). The composition

indicate that the dwellers of the Early Horizon

settlement interacted with, used, ate, and pro-

cessed a vast array of wild and domesticated

terrestrial, marine, riverine, and lacustrine

vertebrates including amphibians, reptiles, fish,

birds, and mammals. Mammals (NISP=1661,

50.50 percent) account for about half of the

NISP values followed by fish (NISP=1218,

37.03 percent), and birds (NISP=308, 9.36

percent). Amphibians (NISP=73, 2.22 percent)

and reptiles (NISP=29, 0.88 percent) are mar-

ginal. With 36 and 20 species, respectively, fish

and bird taxa display overall more richness than

mammals (n=8) and amphibians (n=1). The

only amphibian identified belongs to the toad

Bufo sp. Soil sample analyses are currently

underway and have revealed the presence of

insects, but entomological data are too prelimi-

nary at this point to evaluate the potential

significance of terrestrial arthropods in human

activities.

Fish. Fish are the richest category with some

fresh, but mostly salt water species. In our

Nepeña (9ºS) assemblage, most marine fish are

typical of the Peruvian Province (5ºS–40ºS),

although two species (Larimus sp., Pareques sp.)

are also common in the warmer province of

Panama (5ºS-5ºN). Marine fish can potentially

travel through and inhabit diverse oceanic

biotopes including deeper offshore waters, as

well as shallower near shore coastlines. Based on

documented fishing techniques for the Early

Horizon, typical location of fish habitats (mostly

demersal and benthonic), and oceanic substrates

(mostly sandy), most fish could have been

caught in shallow waters (mostly up to forty

meters) of the shore of the Bahía de Samanco

using a combination of fishing lines, weights,

floaters, hooks, and nets.

Overall, the fish assemblage is rich, but

exhibits relatively little diversity, with the five

most common taxa accounting for more than 60

percent of the fish remains. More than 30

percent of the fish remains belong to sardines

(Sardinops sagax sagax) (NISP=378, 31.03

percent of total fish), followed by drums and sea

basses of different sizes (Sciaena sp.)

(NISP=119, 9.77 percent). Cabrillas (Parala-

brax sp.) (NISP=44, 3.61 percent), anchovies

(Engraulis ringens) (NISP=32, 2.63 percent),

giltheads (Micropogonias altipinnis) (NISP=31,

2.55 percent), mullets (Mugil cephalus)

(NISP=27, 2.22 percent), mojarillas (Stellifer

minor) (NISP=26, 2.13 percent), Pareques sp.

(NISP=23, 1.89 percent), saurels (Trachurus

symmetricus) (NISP =22, 1.81 percent), bonitos

(Sarda chilensis) (NISP=20, 1.64 percent), sting

rays (Myliobatis sp.) (NISP =18, 1.48 percent),

459 - Research Reports

and banded croackers (Paralonchurus peruanus)

(NISP=14, 1.15 percent) are found in lesser

quantities. The low frequency of anchovies and

their limited distribution (found only at Plaza-

A), are surprising, considering the common

presence of these taxon at coastal archaeological

deposits. Finally, numerous fish taxa are found

in less than one percent of the fish remains

including several species of teleost and cartilagi-

nous fish. The latter are rare in the Early Hori-

zon contexts sampled so far at Caylán

(NISP=42, 3.45 percent). They include sand

sharks (Mustelus sp.), hammer sharks (Sphyrna

sp.), tiburon sharks (Carcharhinus sp.), and sting

rays (Myoliobatis sp.).

Birds. Birds display a less rich, but more

diverse assemblage, especially considering edible

taxa. Of the total of twenty identified avian

taxa, the medium size dove Zenaida asiatica

(NISP=74, 28.14 percent of total bird remains)

is by far the most common and ubiquitous bird

at Caylán. More remains of the Columbidae

family were encountered (NISP=10). Today,

these birds dwell in bushes, trees, and fields in

the vicinity of Caylán. In the Early Horizon, wild

birds could have been hunted with a variety of

projectile weapons including slings and spears,

as well as nets. Columbidae are followed by

cormorants (Phalacrocorax bougainvillii) (NISP=

27, 10.27 percent), and seagulls (Larus sp.)

(NISP=26, 9.89 percent). Wild ducks (Anas

sp.) (NISP=12, 4.56 percent), medium size

icterids (Sturnella sp.) (NISP=11, 4.18 percent),

and black vultures (Coragyps atratus) (NISP=

11, 4.18 percent) are also present in lesser

frequencies. The remains of vultures are re-

stricted to UE6 in a single context within

Compound-E. They are unlikely to have played

a major role in local subsistence. A similar

observation can be made about the remains of

owls (Stigidae cf. Asio sp.) and swallows (Hirun-

do sp.). Other marginal species–that could,

nevertheless, have played an economic role in

Early Horizon Nepeña–include the marshland

taxa Egretta sp. (NISP=1, 0.38 percent) and

Gallinula chloropus (NISP=1, 0.38 percent), and

marine penguins (Puffinus sp.) (NISP=2, 0.76

percent).

Finally, a proximal section of a condor

(Vultur gryphus) ulna was recovered from

Mound-A construction fill. It displays cut marks

suggesting the production of musical instru-

ments. Overall, the taxonomic analysis of bird

remains indicates the exploitation of the lagoon

and marshlands adjacent to the urban settle-

ment of Caylán. Meanwhile, marine taxa appear

limited to cormorants and seagulls.

The Caylán zooarchaeological sample is still

limited and more research is needed, but the

scarcity of penguin remains could be significant,

especially since sea lions–who inhabit similar

environments–are documented more systemati-

cally. It could, for instance, indicate that

Nepeña people obtained sea lion products

through extra-local exchange networks, includ-

ing salted meat, teeth for adornments, and

bones for tools. Although it implies the more

limited movements of penguin products within

exchange networks, this working hypothesis is

consistent with the near shore fishing strategies

postulated for Early Horizon times in Nepeña.

Perhaps more importantly, some bird taxa are at

the moment completely absent from the Caylán

osteological sample. The more salient absence is

related to the Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata),

although the absence of pelican (Pelecanus sp.),

booby (Sula sp.), and heron (Casmerodius albus)

is also notable.

In sum, bird resources at Caylán appear less

systematic and more opportunistic compared to

fish and mammalian taxa. Bird domesticates

have so far to be documented, and most of the

wild taxa include small to medium size animals.

Hunting was clearly a significant option to

acquire animal protein, but the relatively small

size and low demographic densities of these

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022) - 460

birds do not lend weight to these animal re-

sources being sustainable for a dense urban

population. Rather, it appears that Caylán

residents more systematically consumed marine

fish and shellfish, as well as mammals.

Mammals. At Caylán, the role of camelids

appears undeniable as a pack animal, a source of

meat and bone, and perhaps of fibers. Camelids

dominate the osteological assemblage with 437

NISP for 37.41 percent of all mammalian re-

mains. Our osteometric analysis of camelids

focused on first phalanges of three individuals.

Results indicate that the three Caylán speci-

mens pertain to a single taxon highly consistent

with llamas (Lama glama). They are followed by

dogs (Canis familiaris) (NISP=263, 22.52 per-

cent), guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) (NISP=235,

20.12 percent), chinchillas (Lagidium peruanum)

(NISP=20, 1.71 percent), sea lions (Otaria sp.)

(NISP=15, 1.28 percent), felines (Felis sp.)

(NISP=6, 0.51 percent), and white tail deer

(Odocoileus virginianus) (NISP=4, 0.34 percent).

Llamas, dogs, guinea pigs, and chinchillas are

ubiquitous throughout the excavation units,

while the distribution of felines, sea lions, and

deer appears more limited. It is unlikely that the

Caylán felines were consumed as foods. In

contrast, llama and dog remains display traces of

butchering, and burning.

Anatomical

part

Mound-A Plaza-A Compound-E

N% N% N%

Cranium 12 14.8 3 6.1 10 13.7

Thorax 36 44.4 24 49.0 25 34.2

Anterior limbs 11 13.6 8 16.3 22 30.1

Posterior limbs 13 16.0 8 16.3 9 12.3

Feet 9 11.1 6 12.2 7 9.6

Total 81 100.0 49 100.0 73 100.0

Table 2. Anatomical distribution of camelid re-

mains.

For the llamas, the distributional analysis of

anatomical parts across the three main contexts

of area excavations at Caylán– Mound-A, Plaza-

A, and Compound-E–indicates consistency

(Table 2). Throughout the excavation contexts,

sections of thorax dominate the llama remains,

ranging from 34.2 percent of the total llama

remains at Compound-E to 49 percent at Plaza-

A. Anterior and posterior limbs follow in impor-

tance. Meanwhile, remains of crania and feet

appear relatively on a par with limbs, depending

on the context. Out of the 203 bones recovered

at Mound-A, Plaza-A, and Compound-E, cut

marks are present on 23 bones (11.33 percent),

while 19 (9.36 percent) are burnt. The majority

of the cut marks were observed on ribs

(NISP=14, 60.87 percent of total cut marks)

suggesting that the body parts were especially

prized.

Dog remains are surprisingly abundant and

ubiquitous at Caylán. All excavation units have

yielded dog remains, several of them showing

cut marks, in particular on limb bones. Cut

marks on limbs indicate that dog meat was

consumed. It is significant that Shibata (2013)

reports on the high frequency of dog bones in

the feasting refuse at Cerro Blanco. While

Shibata suggests that dogs might have related to

feasting activities and the supplying of high

status guests and visitors, the ubiquity of dog

remains at Caylán suggests a more widespread

consumption, perhaps beyond elite and feasting

contexts.

Guinea pigs are also well represented at

Caylán. The animals were likely consumed and

used in ritual divination and other special

activities. Finally, deer, sea lion, and chinchilla

are represented in lesser frequencies. Deer were

likely hunted from the lomas and adjacent

forested areas around Caylán. However, their

limited occurrence indicates that this wild game

was likely of minor importance in the overall

diet, in contrast to domesticated camelids, dogs,

and guinea pigs.

461 - Research Reports

Summary and Conclusions

The taxonomic analysis of the vertebrate

remains at Caylán indicates that Early Horizon

populations in the lower Nepeña Valley ex-

ploited different littoral and inland wild re-

sources from diverse biotopes including sandy

beaches, fresh water lagoons, marshlands, lomas,

and woodlands. The relative importance of each

of these in local subsistence and meat input is

still unclear, but in light of the richness, diver-

sity and ubiquity of fish remains, it appears the

sea provided the most systematic source of

animal protein. Most fish remains pertain to

small to medium size fish such as sardines,

drums, and sea basses likely caught from the

Samanco shoreline. Larger fish such as sharks

and bonitos are less common. The richness and

diversity of fish suggests a combination of vari-

ous fishing strategies including lines and nets.

Fish data suggest that these animals–mainly

teleost fish–were at the core of daily subsistence

for most people at the urban site. Sea birds and

mammals are also present, albeit in lesser fre-

quencies.

The high richness and diversity, yet low

frequency of bird remains suggest an opportunis-

tic exploitation of waterfowls and other small

birds living around Caylán, perhaps by a limited

number of hunters. It is unclear at this point

whether these small birds were prized as foods.

In contrast, the high frequency and low richness

of domesticated mammals point towards a more

systematic and intense exploitation.

Animal domesticates were critical to Caylán

dwellers, especially llamas for transportation,

meat, and fibers. Although it is unclear whether

camelids were consistently raised and main-

tained within the urban settlement, anatomical

and taphonomic data indicate that llamas were

butchered locally. Whole carcasses were avail-

able and diverse body parts were processed,

consumed, and discarded on site. Other primary

meat sources include dogs and guinea pigs,

although they might have been limited to spe-

cial occasions including feasts.

To conclude, this report has presented and

discussed the results of the preliminary analysis

of vertebrate osteoarchaeological remains from

the Early Horizon urban center of Caylán,

Nepeña Valley (Ancash) Peru. Insights into

human-animal interactions at Caylán are partic-

ularly important to shed light on the process of

urbanization that occurred in coastal Ancash

during the first millennium B.C. Research

indicates the emergence of a dense urban ag-

glomeration where most dwellers could have

been detached from primary subsistence activi-

ties and supplied by neighboring farmers, hunt-

ers, herders, and fishers. Such socioeconomic

transformations had a profound effect on animal

exploitation.

Results indicate that the Caylán deposits

contain a rich assemblage dominated by mam-

mals, fish, and birds. In terms of richness, most

are wild taxa, but the higher frequency of

camelids, dogs, and guinea pigs indicate the

importance of animal domesticates in economic

practices. Osteometric analyses indicate that the

Caylán camelids were llamas. Although it still

unclear whether large scale herding facilities

were present at Caylán, llamas clearly occupied

a privileged place within Early Horizon diets and

socioeconomics. Based on their ubiquity and

frequency, dogs and guinea pigs were other

significant mammals consumed onsite. Marine

fish and shellfish represented another viable,

predictable, and heavily exploited source of

animal protein. In contrast, birds were preyed

upon opportunistically in and around the

Caylán lagoon marshlands.

The Caylán osteoarchaeological analysis

indicates the trend of increased reliance on

animal domesticates, mostly camelids and

guinea pigs–which in Nepeña appears to have

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022) - 462

begun during the transition from the Cerro

Blanco to Nepeña Phase around 800 B.C.–

gained momentum when people settled into

more urban lifeways. The sea continued to

provide rich, diverse, and heavy supplies of

animal products including fish and shellfish, but

llamas probably represented one of the most

valued animal resources for transportation,

meat, bones, and hair.

Comparisons of zooarchaeological assem-

blages from neighboring Early Horizon sites

suggest the existence of interdependent commu-

nities. From that standpoint, urban dwellers

were supplied by indirect systems of resource

management and distribution. However, little

evidence exists at the moment to lend weight to

the existence of top-down control from Caylán,

the largest settlement and hypothesized primary

center of the integrated lower Nepeña system.

Rather, animal products appear to have been

channeled through a multitude of more or less

independent networks. More data are needed

on the cultivation practices and the manage-

ment of surplus crops, but the Caylán animal

research calls for a reassessment of hegemonic

economic models in the context of incipient

urbanism, and a consideration of the complexity

and heterogeneity of human-animal interactions

in the development of Andean civilizations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Fieldwork at Caylán was sponsored by Louisiana State

University’s Office of Research and Economic Develop-

ment and the Department of Geography and Anthropol-

ogy. Laboratory analyses were funded by a grant from the

Louisiana Board of Regents (contract number

LEQSF[2011-2014]-RD-A-05). Thanks go to the

Ministerio de Cultura del Perú for considering favorably

and supervising the field project (excavation permits

804/INC-050609, 1230/INC-280510), as well as to Hugo

Ikehara who co-directed the excavations.

R

EFERENCES CITED

Chicoine, David, Beverly Clement, and Kyle Stich

2016 Macrobotanical Remains from the 2009 Season

at Caylán: Preliminary Insights into Early Hori-

zon Plant Use in the Nepeña Valley, North-

Central Coast of Peru. Andean Past 12:155–161.

Chicoine, David and Hugo Ikehara

2014 Ancient Urban Life at the Early Horizon Center

of Caylán, Peru. Journal of Field Archaeology

39(4):336–352.

Chicoine, David and Carol Rojas

2013 Shellfish Resources and Maritime Economy at

Caylán, Coastal Ancash, Peru. Journal of Island

and Coastal Archaeology 8(3):336–360.

Shibata, Koichiro

2013 Food for Visitors? An Unusual Consumption of

the Canis in the Feasting Activities at the For-

mative Ceremonial Center of Cerro Blanco,

Peruvian North Central Coast. Poster presented

at the 78th Annual Meeting of the Society for

American Archaeology, Honolulu, Hawaii, April

5.

463 - Research Reports

A Peruvian Central Coast Mortuary

Assemblage in the Logan Museum of

Anthropology, Beloit College

Kylie E Quave(George Washington Univer-

Heaney (Pennsylvania State University, cuh282

@psu.edu) report on a Peruvian Central Coast

mortuary assemblage in the Logan Museum of

Anthropology. This report is the first of a set of

three outlining recent analyses–both visual and

archaeometric–of an assemblage purportedly

originating from a single mortuary context in

the Rimac Valley, and with objects dating to the

Late Intermediate Period and the Late Horizon.

The objects within this assemblage compare

with Ychsma and Inca goods from the Central

Coast in the centuries leading up to Spanish

contact (c. A.D. 1050–1532). In this first report

we outline the historical and archaeological

contexts of the assemblage (its provenance or

collection history and its provenience or archae-

ological find location) and the contents of the

assemblage. A brief biographical insight into the

assemblage’s collector Alpheus Hyatt Verrill

(1871–1954) contextualizes relationships be-

tween North Americans and Peruvians in the

1920s, a time of practical transition in the wake

of hardening legal norms governing excavation

and the exportation of artifacts (Heaney 2012).

Collection history

The collection analyzed here was purchased

by the Logan Museum of Anthropology at Beloit

College in Beloit, Wisconsin (LMA) from

renowned explorer, naturalist, and science

fiction writer A. Hyatt Verrill in 1929. On 7

August of that year, Verrill offered the assem-

blage to the LMA as a “mummy bundle from

Rimac Valley” that included seventy-six objects:

ceramic vessels and a figurine, woven clothing

and bags, coca paraphernalia, a quipu “work

kit,” metal adornments, and various wooden

and bone artifacts.

The course by which a North American

explorer came into possession of a “mummy

bundle” illustrates the difficulties and opportu-

nities of its analysis, and offers insights for the

triangulation of other decontextualized artifacts

from this era. Verrill is an appropriately chal-

lenging vehicle for such an approach. The

author of more than one hundred and five

books, many of them popular non-fiction, Verrill

conducted ethnological and archaeological

fieldwork in the Americas, but his interest in

antiquities was tinged with controversy from its

beginning. Around age 25, he was accused of

selling stolen artifacts from Yale University’s

Peabody Museum (Anonymous 1896). Though

newspaper coverage of the scandal referred to

him as “Albert Hyatt Verrill,” the subject was

evidently Alpheus Hyatt Verrill: he was de-

scribed as the “eldest son of Addison E. Verrill,

M.A., professor of zoology and curator of the

zoological collection at the museum” and the

spouse of “Miss [Kathryn L.] McCarthy.” Both

of these relationships exclusively describe Hyatt

Verrill (ibid.). Hyatt Verrill was believed to have

absconded with at least $10,000 worth of “cu-

rios” (worth perhaps $300,000 today), and the

police recovered materials from dealers to whom

he had sold the artifacts. Additionally, authori-

ties charged that he had replaced many of the

items stolen from the museum with fakes he had

crafted to avoid discovery. The newspaper’s

report emphasized that Verrill had a sound

reputation, and that his father took responsibil-

ity for minimizing the damages to the Peabody;

his father and the Peabody’s Curator of Geol-

ogy–Othniel Charles Marsh, who had been

instrumental in the museum’s founding and

directed it until his death in 1899–asserted the

damages were not more than $100 to $1,000.

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022):463–477.

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022) - 464

When Verrill wrote to the Logan Museum

in 1929, however, it was as someone who col-

lected antiquities for museums, not from them.

In the three decades since the Peabody thefts,

he had established himself as a writer, collector

of ethnographic pieces, and excavator of pre-

Columbian artifacts. His turn to Peru was coeval

with the second presidency (1919–1930) of

Augusto B. Leguía, whose awards of artifacts

and export concessions via executive decree

during his first term (1908–1912) had helped

harden Peruvian legal norms against the excava-

tion and exportation of artifacts by foreigners

(Heaney 2012: 154–156, 185–222). During

Verrill’s initial visit to Peru, between 1924 and

1926, he met Leguía, and enjoyed a grave-

opening expedition outside Lima led by Mar-

shall Saville, of George Heye’s Museum of the

American Indian (Verrill n.d.). In 1929, he

returned with a commission to excavate and

collect for Heye. Leguía accepted Verrill’s

proposal “to collect Peruvian antiquities”, and

directed him to Julio César Tello, the Harvard-

trained director of the first national Museo de

Arqueología (MAP), who had previously collab-

orated with North American anthropologists

like Alfred Kroeber (Peters and Ayarza 2013),

and now met with Verrill as well.

This association later was used to force Tello

from the directorship of his beloved museum. In

1930, after his patron Leguía was overthrown, a

series of articles in the revolutionary newspaper

Libertad leveled several charges against Tello,

one of which was that he had colluded with

Verrill to smuggle seventeen crates of artifacts

out of the port of Callao. Richard Daggett has

characterized this smear campaign as less than

credible. The accuser signed his salacious arti-

cles with pseudonyms and “mixed truth with

half-truths and out-and-out lies, wrapped them

in patriotic rhetoric, and served them up with-

out a hint of supporting documentation”, Dag-

gett concludes. “It was mudslinging pure and

simple” (Daggett 2009:32).

The archives of the LMA, the Penn Mu-

seum, and the Museo Nacional de Arqueología,

Antropología y Historía del Perú (MNAAHP)

provide additional perspectives on the politics of

Verrill’s collecting and selling. During his first

meeting with Tello, on 20 March 1929, Verrill

revealed that one of Tello’s former lieutenants,

Antonio Hurtado, had tried to sell him an

impressive Paracas textile apparently stolen

from the MAP for £2,500, which Tello “imme-

diately proceeded to investigate” (Anonymous

1929–1930); see also Daggett 2009; Peters and

Ayarza 2013). Tello’s gratitude–and Leguía’s

prior recommendation– presumably then led the

Peruvian to permit the American to excavate

and export a collection of artifacts “duplicate”

to those in the MAP.

A week and a half after their first meeting,

Verrill again visited Tello to request permission,

in the name of Heye’s museum, to export “24

huacos and other objects well represented in the

collections of the [MAP].” On 25 April, Tello

requested Verrill’s credentials, and asked that

he submit “to the same rigorous conditions

stipulated to Dr. Kroeber in the identical case”

(ibid.). Verrill seems to have been certain of

approval because on 15 April he had written to

Penn to offer dozens of objects from mostly

coastal prehispanic cultures: Chimú, Nazca, and

Inca. He was in Peru, he explained, and “am in

an unusual position to secure almost anything

that you may require to fill gaps in your collec-

tions, and shall be very glad to try to get what-

ever you want”–apparently on top of what he

was collecting for Heye (15 April 1929).

The Penn Museum was slow to respond.

Verrill was a “very well known amateur anthro-

pologist”, Penn curator J. Alden Mason ob-

served, but “must be dealt with cautiously . . .

from a business point of view” (Mason n.d.) and,

in the interim, Verrill stayed busy. On 28 April,

he and Tello made an excursion to Pachacamac,

and in the weeks following he helped document

465 - Research Reports

a number of Tello’s now-famous unwrappings of

Paracas mummy bundles. On 25 May, the

museum approved his request to export “21

huacos” also “duplicated” in its collection

(Anonymous 1929–1930), and on 21 June,

Verrill wrote to Penn regarding an additional list

of 55 objects, which included the “Contents of

mummy bundle from Rimac valley”, described

below, and a lot of “contents of mummy bundle

from Pachakamak consisting of rope netting,

basket for carrying loads, basket work receptacle

containing mummy of a dog, mummy wrappings,

textiles, cotton pouches, small mummy mask of

wood, stone beads, etc.” (Verrill 1929d). Mason

finally expressed interest in the collection, but

noted that “the only thing in which we would

certainly not be interested is the Pachacamac

mummy bindle [sic]” (Mason 1929, emphasis

added), an unsurprising demurral given that

Penn’s Peruvian collection centered on Max

Uhle’s 1890s Pachamacac excavations.

The “mummy bundle from Rimac valley”,

however, went to the LMA. In July, Verrill

wrote to LMA curator George Collie to offer

artifacts from his collection, composed during

eight years of “archaeological explorations”

(Verrill 1929b:1). Collie responded with inter-

est, and on August 7th Verrill sent an inventory

of 63 lots resembling the second Penn list, with

a few objects of the former now excluded–like

the “mummy bundle from Pachakamak”–and a

few new ones appended. Verrill seemed eager to

dispose of his archaeological finds, as he told

Collie that he would “be very glad to make a

very low and attractive offer if you could take

the lot” (Verrill 1929c:1). The only lot pur-

chased was the assemblage discussed here,

which Verrill described to both museums as:

Contents of mummy bundle from Rimac

valley consisting of: Textiles, pouches,

“medicines”, hard wood weapon, silver

collar, necklace of seeds and nuts, neck-

lace of copper objects, bronze pin, wooden

labret, gourd flasks, bronze crescent-shap-

ed knife, carved wooden spoon, carved

wooden llama charm, wooden spatulas,

necklace of human prepuces, bronze pin-

cers, wooden receptacle with fringed cot-

ton stoppers, wood and feather head orna-

ment, pottery vessel, mummy wrappings

etc. (ibid.:3).

Nearly all these objects are now found in a

single accession record for the Verrill purchase,

which Collie wrote to finalize on 28 August of

that year. There was never mention of human

remains in the accession records, and no human

remains have been found in relation to the

objects now in the collection.

Archaeological context

As noted above, Verrill claimed that the

LMA objects had come from a single mummy

bundle in the Rimac Valley, but while analysis

of the remains supports this claim to some

extent, there are reasons to be suspicious of

Verrill’s assertion. For the most part, the objects

that possess culture-specific characteristics point

to an archaeological provenience in the Late

Intermediate or Señorío Period and the Inca

Horizon, placing the objects around A.D. 1050–

1530, and within the Ychsma/Ychsma-Inca

culture area.

The Ychsma were native to the Pachacamac

province and became an administrative unit of

the Incas after a relatively peaceful annexation

around 1470 (Rostworowski 2002:83). Settle-

ments were located within the Lurín, Chillón,

and Rimac Valleys (Díaz and Vallejo 2002:357–

358). As a macroethnic group, the Ychsma were

composed of smaller polities integrated within

the larger region (Rostworowski 2002:82).

Ychsma-Inca funerary contexts on the

Central Coast include both simple subterranean

graves and elaborate above-ground structures.

ANDEAN PAST 13 (2022) - 466

Individuals were interred in seated, flexed

position and wrapped in layers of textiles and

bundles of raw cotton, with a net or reed mat

around the exterior. Bundles included food-

stuffs, textiles, raw cotton, gourds, metal goods,

and other, smaller bundles (Díaz 2004, 2015;

Eeckhout 2002; Frame et al. 2004, 2012; Owens

and Eeckhout 2015; Takigami et al. 2014; Uhle

and Shimada 1991 [1903]). Some funerary

bundles contained more than one individual, as

may be the case for the LMA assemblage. Be-

cause the bundle was brought to the museum

already opened and without human remains, it

is impossible to know what else, if anything, was

interred with it. Some of the intially catalogued

artifacts have not been found in recent years,

namely the “bronze crescent-shaped knife”, the

“necklace of human prepuces” (which would be

unusual), a bronze pin, and a silver collar.

Contents of the assemblage

Ceramic objects. Three ceramic objects

arrived with the Verrill assemblage: a hollow

human figure (Figure 1), a provincial Inca

narrow-mouth jar (aryballoid vessel) (Figure 2),

and an Ychsma bottle (Figure 3). The figurine

resembles Late Ychsma examples (Vallejo 2004: