NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

EMIGRATION DURING THE FRENCH REVOLUTION:

CONSEQUENCES IN THE SHORT AND LONGUE DURÉE

Raphaël Franck

Stelios Michalopoulos

Working Paper 23936

http://www.nber.org/papers/w23936

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

October 2017

We would like to thank Sascha Becker, Davide Cantoni, Guillaume Daudin, Melissa Dell, Oded

Galor, Paola Giuliano, Moshe Hazan, Ruixue Jia, Oren Levintal, Omer Moav, Ben Olken, Elias

Papaioannou, Gerard Roland, Nico Voigtlaender, David Weil, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya as well

as seminar participants at Brown, Harvard, Harvard Kennedy School of Government, Hebrew

University of Jerusalem, NBER Summer Institute Political Economy & Income Distribution and

Macroeconomics Workshop, Northwestern Kellogg, Paris-1, Princeton, Insead, NUS, Hong Kong

University of Science and Technology, Sciences-Po, Tel Aviv, IDC Herzliya, Toronto, Warwick,

and conference participants at the European Public Choice Society Meeting, the Israeli Economic

Association conference, and the Warwick/Princeton conference for valuable suggestions. We

thank Bernard Bodinier, Martin Fiszbein, and Nico Voigtlaender for sharing their data. We would

also like to thank Nicholas Reynolds for superlative research assistance. All errors are our own

responsibility. Stelios Michalopoulos and Raphael Franck have no relevant financial support to

disclose in relationship to this project. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do

not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been

peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies

official NBER publications.

© 2017 by Raphaël Franck and Stelios Michalopoulos. All rights reserved. Short sections of text,

not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full

credit, including © notice, is given to the source.

Emigration during the French Revolution: Consequences in the Short and Longue Durée

Raphaël Franck and Stelios Michalopoulos

NBER Working Paper No. 23936

October 2017

JEL No. N10,O10,O15

ABSTRACT

During the French Revolution, more than 100,000 individuals, predominantly supporters of the

Old Regime, fled France. As a result, some areas experienced a significant change in the

composition of the local elites whereas in others the pre-revolutionary social structure remained

virtually intact. In this study, we trace the consequences of the émigrés' flight on economic

performance at the local level. We instrument emigration intensity with local temperature shocks

during an inflection point of the Revolution, the summer of 1792, marked by the abolition of the

constitutional monarchy and bouts of local violence. Our findings suggest that émigrés have a

non monotonic effect on comparative development. During the 19th century, there is a significant

negative impact on income per capita, which becomes positive from the second half of the 20th

century onward. This pattern can be partially attributed to the reduction in the share of the landed

elites in high-emigration regions. We show that the resulting fragmentation of agricultural

holdings reduced labor productivity, depressing overall income levels in the short run; however, it

facilitated the rise in human capital investments, eventually leading to a reversal in the pattern of

regional comparative development.

Raphaël Franck

Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Department of Economics

Mount Scopus

Jerusalem 91905

Israel

Stelios Michalopoulos

Brown University

Department of Economics

64 Waterman Street

Providence, RI 02912

and NBER

1 Introduction

Tracing the origins and consequences of major political upheavals occupies an increasing part of

the research agenda among economists and political scientists. The Age of Revolution in Europe

and the Americas, in particular, has received much attention as these major political disruptions

are thought to have shaped the economic and political trajectories of the Western world toward

industrialization and democracy. This broad consensus concerning their paramount importance ,

nevertheless, goes in tandem with a lively debate regarding the exact nature of their consequences.

The voluminous literature on the economic legacy of the French Revolution attests to this.

On the one hand, there is a line of research that highlights its pivotal role in ushering the

French economy into the modern era. This perspective, which begins with 19th century thinkers

of di¤erent persuasions such as Thiers (1823–1827), Guizot (1829-1832), and Marx (1843 [1970])

and is continued during the 20th and 21st centuries by broadly left-leaning scholars (e.g., Jaurès

(1901-1903), Mathiez (1922-1924), Soboul (1962), Hobsbawm (1990), Garrioch (2002), Jones

(2002), and Heller (2006)), views the 1789 French Revolution as the outcome of the long rise

of the bourgeoisie, whose industrial and commercial interests prevailed over those of the landed

aristocracy. These authors, in making their case, stress the bene…ts from the weakening of

the Old Regime as manifested in the abolition of the feudal system, the consolidation of private

property, the simpli…cation of the legal system, and the reduction of traditional controls and …scal

hindrances to commerce and industry. However, the scholars, who argue that the reforms brought

about by the French Revolution were conducive to economic growth (e.g., Crouzet (2003)), are

aware of France’s lackluster e conomic performance during the 19th century vis-à-vis England

and Germany, and attribute it to the political upheavals that characterized the country and the

violence of the Revolution and Napoleonic Wars.

On the other hand, mostly liberal or conservative intellectuals (e.g., Taine (1876-1893),

Cobban (1962), Furet (1978), Schama (1989)) emphasize that France remained largely agricul-

tural vis-à-vis England and Germany until 1914. They argue that the French Revolution was

not motivated by di¤erences of economic interests between the nobility and the bourgeoisie, but

was rather a political revolution with social and economic repercussions (Taylor (1967), Aftalion

(1990)).

1

They consider that the French Revolution was actually “anticapitalist”contributing to

the persistent agricultural character of France during the 19th century. Besides the cost of war

and civil con‡ict, these studies emphasize the development of an ine¢ cient bureaucracy and the

adverse impact of changes in land holdings on agriculture.

In this study we attempt to shed some light on the short- and long-run economic conse-

1

Maza (2003) in fact argues that there was no genuine French bourgeoisie in 1789 as none of the politicians

deemed to represent the bourgeoisie expressed any consciousness of belonging to such a group.

1

quences of the French Revolution across départements (the administrative divisions of the French

territory). Speci…cally, we exploit local variation in the weakening of the Old Regime, re‡ected in

the di¤erent emigration rates across départements. During the Revolution, more than 100; 000 in-

dividuals emigrated to various European countries and the United States (Greer (1951)). Among

the émigrés, nobles, clergy membe rs, and wealthy landowners were disproportionately repre-

sented.

While the …rst émigrés left as early as 1789, the majority actually ‡ed France, during an d

after the summer of 1792 (Taine (1876-1893), Duc de Castries (1966), Bouloiseau (1972), Boisnard

(1992), Tackett (2015)), when the Revolution to ok a radical turn which French historian Georges

Lefebvre has called the “Second Revolution”(Lefebvre (1962)). During that summer, following

the arrest of King Louis XVI on August 10 and the “September Massacres” in Paris (Caron

(1935), Bluche (1992)), the hitherto uneasy coexistence of the monarchy and the revolutionaries

came to an abrupt end with the proclamation of the Republic on September 21, 1792. Four

months later, King Louis XVI was guillotined.

Our identi…cation strategy exploits local variation in temperature shocks at this in‡ection

point of the French Revolution (i.e., the summer of 1792) to get plausibly exogenous variation in

the rate of emigration across départements. The logic of our instrument rests on a well-developed

argument in the literature on the outbreak of con‡ict that links variations in economic conditions

to the opportunity cost of engaging in violence. To the extent that temperature shocks decrease

agricultural output (which we show to be the case in our historical context), an increase in the

price of wheat (the main staple for the Fren ch in the 18th century)

2

would intensify unrest among

the poorer strata of the population, thereby magnifying emigration among the wealthy supporters

of the moribund monarchy. Consistent with this argument, we show that, in August and Sep-

tember 1792, there were more peasant riots in départements that experienced larger temperature

shocks.

3

It is worth pointing out that the temperature shocks in the summer of 1792 are mild

compared to other years during the Revolution, thereby suggesting that ordinary income ‡u ctua-

tions at critical junctures may have a persistent e¤ect on subsequent development. Importantly,

temperature sho cks during the other years of th e Revolution predict neither emigration rates nor

subsequent economic performance.

Our …ndings suggest that émigrés have a nonmonotonic impact on comparative economic

performance unfolding over the subsequent 200 years. Namely, high-emigration départements

have signi…cantly lower GDP per capita during the 19th century but the pattern reverses over

the 20th century. Regarding magnitudes, an increase of half a percentage point in the s hare of

2

On the i mportance of wheat and bread in France in the 18th century, see, for example, Kaplan (1984) and

Kapl an (1996). See also Persson (1999) on grain m arkets during this period.

3

Al ong the same lines, Grosfeld, Sakalli, and Zhuravskaya (2017 ) …nd that anti-Jewis h pogroms in eas tern

Europe between 1800 and 1927 occurred w hen poor h arvests coincided wit h institutional and political uncertainty.

2

émigrés in the population of a département (which is the mean emigration rate) decreased GDP

per capita by 12:7% in 1860 but increased it by 8:8% in 2010.

Pinning down the exact mechanism(s) via which emigration shaped local economic per-

formance is challenging. Thanks to the detailed French historical census es, we attempt to shed

some light on this issue. A signi…cant fraction of the émigrés were landowners so their exodus is

likely to have in‡uenced the composition of local landholdings. Using th e agricultural census of

1862, we show that high-emigration départements have fewer large landowners and more small

ones. Indeed, the size of the average farm in France in 1862 was 23:12 acres, smaller than the

average farm of 115 acres in England in 1851 and the average farm of 336:17 acres in the United

States in 1860 (Shaw-Taylor (2005), Fiszbein (2016)).

4

This legacy of fragmented landholdings

has remained largely in place in France to this day. Furthermore we show that, during the 19th

century, this reduction in the preponderance of large private estates and the development of a

small peasantry had a negative impact on agricultural p roductivity by limiting the adoption of

scale-intensive mechanization methods. Moreover, we …nd that the share of rich individuals in

the population of high-emigration départements during the 19th century was signi…cantly smaller

compared to regions where few émigrés left. This absence of a critical mass of su¢ ciently wealthy

individuals in the era of capital-intensive modes of production may also explain the slow pace of

industrialization in the h igh-emigration départements during the 19th century.

Interestingly, as early as the midd le of the 19th century, these agriculturally lagging dé-

partements register slightly higher literacy rates than their richer, agriculturally more produc tive

peers. This modest educational edge widens during the early 20th century, after the French state

instituted free and mandatory schooling, eventually translating to higher inc omes per capita in

the later part of the 20th century. This …nding h ighlights that historical legacies may crucially

interact with state-level policies and is consistent with recent studies in developing c ountries

which show that increases in agricultural productivity red uce school attendance by increasing

the opp ortunity cost of schooling (see, e.g., Shah and Steinberg (2015)). By establishing a causal

link between the rate of structural transformation across regions in France and the inte nsity of

emigration, we shed new light on an intensely debated topic, that is, the economic legacy of the

1789 Revolution within France.

5

4

In Appe ndix Table D.1, we dis tinguish between French départements and US counties which were above and

below the median value of grain production in 1862 and in 1860, respectively. We a lso provide descriptive statistics

excludi ng French farms below …ve hectares an d US farms below ni ne acres so as to focus on farmers who were

presumably above subsistence levels. This robustness check is motivated by the fact that the 1860 US census does

not record plots less than t hree acres. Acro ss all di ¤erent metrics, French farms are signi…cantly smaller than the

US ones.

5

To be sure, violence du ring the French Revolution was rampant and multifaceted. Besides the violence of the

crow ds wh ich our identi…cation strategy leverages, where g roups of people vand alized shops and killed civilians and

po liticians (e.g., Jacques de Fles selle, Jean-Bertra nd Fér au d), Gueni¤ey (2011) discusses the top-down planned

annihilation of local populations exempli…ed by the civil war in the Vendée département, the use of the judi cial

3

Related Literature. Our study relates to the literature on the economic consequences

of revolutions and con‡ict. The latter is voluminous (see, e.g., Blattman and Miguel (2010)

for a thorough review) and usually focuses on the impact of these events on the cumulable

factors of production. Recent studies have shifted their attention to the institutional legacies of

con‡ict. In this respect, our work is closely related to Acemoglu, Cantoni, Joh nson , and Robinson

(2011). The latter explores the impact of institutional reform caused by the French occup ation

of German territories. Consistent with the view that barriers to labor mobility, trade and entry

restrictions were limiting growth in Europe, they …nd that French-occupied territories within

Germany eventually experienced faster urbanization rates during the 19th century. In our case, by

focusing on départements within France where the de-jure institutional discontinuities exploited

by Acemoglu, Cantoni, Johnson, and Robinson (2011) are largely absent,

6

we examine whether,

conditional on the nationwide consequences of the radical institutional framework brought forward

by the French Revolution, the local weakening of the Old Regime, re‡ected in the di¤erential

rates of emigration across départements, in‡uenced local development over a signi…cantly longer

horizon. Thus, our study is also closely related to Dell (2012) on the Mexican Revolution. She

…nds that land redistribution was more intense across municipalities where insurgent activity was

higher as a result of droughts on the eve of the Revolution, leading to lower economic performance

today. The latter was due to the fact that the Mexican state maintained ultimate control over

the redistributed land known as ejidos.

By looking at the impact of emigration across départements, our study also contributes to

a growing literature that investigates the economic consequences of disruptions in the societal

makeup of a region. Nunn (2008) and Nunn and Wantchekon (2011), for example, explore the

consequences of the slave trade for African countries and groups, whereas Acemoglu, Hassan, and

Robinson (2011) focus on the impact of the mass execution of Jews during the Holocaust on the

subsequent development of Russian cities.

Finally, our res earch is related to studies by Galor and Zeira (1993) and Galor and Moav

(2004), which argue for a nonmonotonic role of equality in the process of development. When

growth is driven by physical capital accumulation, a larger sh are of su¢ ciently wealthy families

would be bene…cial to local growth during the 19th century. However, areas with more evenly

distributed wealth would experience faster human capital accumulation, translating into better

economic outcomes during the 20th and 21st centuries. Consistent with this argument, we show

that the preponderance of small landowners in the high-emigration départements goes in tandem

system to a ssass inate political opponents durin g the Rei gn of Terror, and the war launched against foreign countries.

Unlike the violence of the crowds, these other types of violence do not seem to have responded to climate-induced

temporary income shocks.

6

See, for example, Soboul (1968) for a discussion regarding the application of the Code Civil and t he persistence

of local institut ions within France during the 19th century.

4

with an earlier takeo¤ in human capital accumulation in these regions.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we describe the historical

background on e migration and land redistribution during the French Revolution. In Section 3

we describe the data and our empirical methodology. In Section 4 we present our main …ndings

and in Section 5 we discuss some of the potential mechanisms that can account for the observed

pattern. In Section 6 we conclude.

2 Historical Background

In 1789, on the eve of the Revolution, France was the largest economy in Europe, with approxi-

mately 25 million inhabitants and lower wages compared to England (see Labrousse (1933) and

Toutain (1987)). Politically, it was a monarchy where King Louis XVI’s subjects were divided

into three orders: the nobility comprising between 150; 000 and 300; 000 members, the clergy

around 100; 000 members, and the Third Estate (artisans, bankers, lawyers, salesmen, peasants,

etc.) made up the rest. This political structure was to end with the Revolution. In Appendix

A:1 we brie‡y discuss its proximate and ultimate causes.

2.1 Emigration during the French Revolution

The April 8, 1792, law de…ned as émigrés all the individuals absent from the département in

which they possessed property, and, as a result of the July 27, 1792, law, their property could be

seized by the French state. The share of émigrés in the population of each département is our key

independent variable. The data were compiled by Greer (1951) from several original governmental

accounts. The sources are mostly o¢ cial publications such as the Liste Générale, par Ordre

Alphabétique, des Emigrés de toute la République (1792-1800) (General List in Alphabetical Order

of Emigrés throughout the Republic), local lists of émigrés, as well as the list of individuals who

received compensation af ter 1825 for the property they lost during the Revolution.

7

Greer (1951)

lists a total of 129; 091 individuals as émigrés.

The revolutionaries were quick to portray all the émigrés as members of the aristocracy who

had prospered on the poverty of French peasants and described them as the living manifestation

of the hostility to the Revolution. Emigrés were both chastised for abandoning the fatherland

to avoid danger in times of political instability and condemned for joining forces with “f oreign

tyrants” against the nation to restore a hated political regime. Revolutionaries thus passed a

series of laws against émigrés, depriving them of their state-funded pensions in 1790, legislating

that emigration was a crime in 1791, and eventually con…scating their property in 1792. In doing

7

France. Ministère des Finances. Eta ts Detaillés des Liquidations faites par la Co mmission d’Indem nité, a

l’époque du 31 décembre 1826 en Execut ion de la Loi du 27 avr il 1825, Paris, D e l’Imprimerie R oyale, 1827.

5

so, some of the revolutionaries were hoping to redistribute land and create a more egalitarian

society, but were disappointed not to see immediate consequences of their policies (e.g., Jones

(1988),Vivier (1998)).

The data collected by Greer (1951) on the émigrés during the Revolution paint a more

nuanced picture than the rhetoric of the revolutionaries, in terms of both the numbe r of émigrés

and their social compos ition. According to Greer (1951), the median département lost 0:31%

of its 1801 population (the …rst year for which we have reliable population data). Panel A

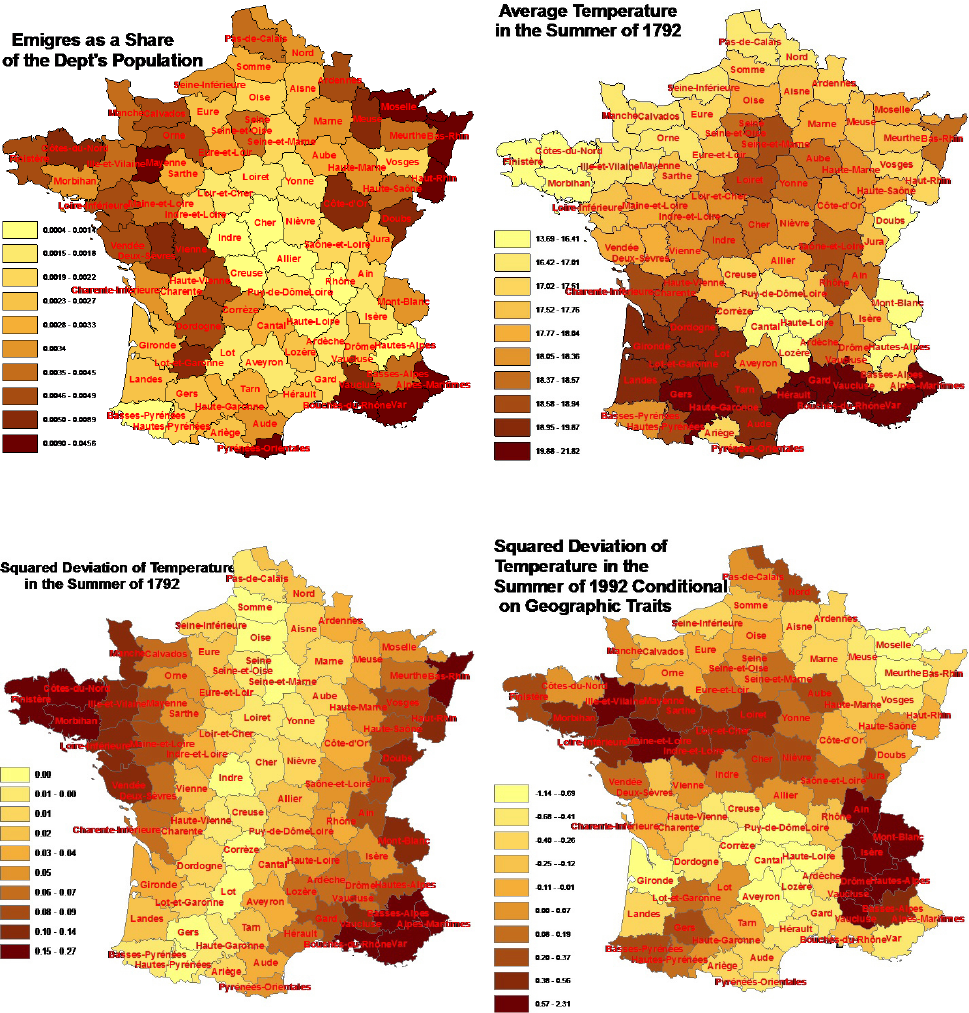

of Figure 1 displays the intensity of émigrés as a share of the population throughout France,

showing substantial spatial variation. Panel A of Table 1 lists the départements with the highest

and lowest emigration rates. Moreover, a substantial fraction of émigrés (but not all of the m)

belonged to the local elites, as can be seen in Panel B of Table 1 for the 69 départements for which

such information is available. They were mainly aristocrats and clergymen, as well as wealthy

urban dwellers and rural landowners from the Third Estate whose property was con…scated and

sold (some even lost the property of the Church that they had acquired in the early stage of

the Revolution).

8

As Panel C of Table 1 shows, the shares of the di¤erent types of émigrés are

strongly correlated. Some of the commoners who left France were servants of aristocrats and

followed their employers abroad. Others were landless peasants or artisans either ‡eeing for their

lives or searching for a better life (see Duc de Castries (1966)).

Revolutionary violence not only took several forms, but also its geographic and social

incidence was markedly di¤erent across French regions and social groups. The civil war was

mostly con…ned to the southeast and west of France, and was particularly intens e in the Vendée

département. The Reign of Terror, which entailed the use of the judicial system to assassinate

political opponents, was more intense in Paris, Lyon and Marseille (i.e., the three main French

cities), as well as in the west of France (Greer (1935), Gueni¤ey (2011)).

9

As such, unlike

the civil war and the judicial Terror, which were s patially concentrated, emigration was for

the contemporaries of the Revolution a spectacular consequence of revolutionary violence that,

at the time, seemed to a¤ect all of France. Moreover, while France under the monarchy had

experienced civil war in the 16th and 17th centuries and while public executions were common

during the 18th century (e.g., Bée (1983), Bastien (2006)), emigration was a speci…c consequence

of the Revolution b ec ause it implied the precipitous decline of a previously conspicuous social

8

On averag e, nobles were richer than peasants, and anecdotal evidence sugges ts that they possessed more land

prior to 1789. Of course, there were exceptions, and the living conditions of some nobles, for instance, those in

Britt any (Nassiet (1993)), were no t really di¤erent from tho se of the peasants. This can explain why before 1789,

po litical antagonism also existed within each of the three orde rs, for example, between min or and gre at nob les

(Furet (1978)). It may also help to ratio nalize why, d uring the Revoluti on, some commoners were favorable to

a c onstitutional monarchy (e.g ., Jean-Joseph Mouni er) while some aris tocrats support ed the radical turn of the

Revolution (e.g., Louis-Michel Le Peletie r de Saint-Fargeau).

9

Greer (1935) repo rts that there were less than 10 executions in 27 départements during the Terror.

6

and political group.

10

In this respect, emigration also di¤ered from the violence stemming from

the civil war and the judicial Terror, which disproportionately a¤ected peasants and workers.

11

2.2 The Intensi…cation of Emigration during the “Second Revolution”

During the summer of 1792, major political upheavals and widespread violence, starting with the

imprisonment of Louis XVI and his family in early August and culminating with the proclamation

of the republic a few weeks later, signi…ed the unraveling of the House of Bourbon and the

abolition of the monarchy. In Appendix A:2 we provide details on the unfolding of these events.

Many historical anecdotes describe how emigration accelerated during and immediately after the

summer of 1792 (e.g., Taine (1876-1893), Bou loiseau (1972), Tackett (2015)).

12

For instance,

reform-minded aristocrats who had played a political role in the …rst years of the Revolution,

such as the Marquis de Lafayette and the Duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, left France in

August 1792. In fact, Tackett (2015) (p. 215) writes that in September 1792, “conditions had

become so frightening that many wealthier families began ‡eeing Paris (...). Others, however,

seem to have concluded that the countryside was even more dangerous than Paris.”An additional

historical piece of evidence pointing to the intensi…cation of the emigration in the fall of 1792 is

the reaction of the British government: it introduced the Aliens Act in the House of Lords on

December 19, 1792, in an attempt to regulate the uncontrolled in‡ux of French nationals, which

created signi…cant anxiety in governmental circles that feared the presence of revolutionary spies

and saboteurs.

Several local historians (listed in Marko¤ (1996)) explicitly link emigration to local episodes

of violence during the su mmer of 1792. For instance, in Var, a high-emigration département, local

violence took the form of several days of rioting in Toulon, between July 28, 1792, and September

10th, 1792, where local revolutionaries targeted aristocrats, military o¢ cers, and wheat traders

whom they considered hostile to the Revolution (Havard (1911-1913)). Members of these groups

‡ed France for Italy. In Ariège a band of peasants led by a local revolutionary began to ransack

and burn castles in late August 1792 (Arnaud (1904)). As a result, many aristocrats, bourgeois,

and refractory priests sou ght refuge in Spain.

10

Many Protestants left France after the revocation of the Edit de Na ntes in 1685 by King Louis XIV (Scoville

(1953)) . However, Fren ch Protestants did not hold the political clout of the aris tocra ts who emigrated, an d their

exodus did not coincide wit h a massive political and economi c tran sformation akin to that of the French Revolution.

11

Greer (1935) estimates (Table 8, pp. 165- 166) that peasants and workers ma de up a combi ned 59:25% of the

total 16; 594 death sentences during the Terror while the nobles were only 8:25%, clergymen 6:5%, members from

the upper middle class 14% and members from the lower middle class 10:5% (no status was given to the remaining

1:5% of individuals sentenced to death). Note that the seemingly low o¢ cial numbe r of victims obscures th e fact

that many more people were kil led without a trial during the Terror .

12

Arguably, some émigrés had ‡ed France befo re the summer of 1792. For instanc e, the Count of Artois, who

would become Ki ng Charles X (r. 1824-1830), left in 1789, and Jean-Joseph Mounier , one of the royalist leaders

of the Amis de la Constitution Mona rchique (Friends of the Mo narchic Constitution ), ‡ed in 1790. A few also left

in the post-Thermidorian period in 1794-1795.

7

2.3 Emigration and Land Redistribution during the Revolution

The sale of the biens nationaux is con side red by some historians as “the most important event

of the French Revolution” (Lecarpentier (1908), Bodinier and Teyssier (2000)). Their claim is

based on the fact that a signi…cant amount of land was seized and sold by the government under

the name of biens nationaux (national goods) during this period. This land belonged to the

Church, the émigrés, and the counterrevolutionaries. The property of the Church was …rst seized

by the French revolutionaries to pay o¤ the debts of the French state on November 2, 1789. The

property of the émigrés and counterrevolutionaries was also con…scated for that purpose three

years later. It is not clear, however, whether the French state recovered much from those sales

due to its in‡ationary policies.

13

In addition, during the French Revolution, property rights were

granted on the villages’commons: some of the common land was sold to private individuals while

some of it was seized by the municipalities and, later on, leased to peasants (Vivier (1998)).

Land redistribution may have been consequential for the French départements for at least

two reasons. First, the amount of land which was seized and sold by the government during the

Revolution was signi…cant; Bodinier (1999) estimates that 10% of land changed hands. Second,

even though émigrés were invited to return to France in 1802 by Napoléon Bonaparte, he forbade

émigrés from reclaiming their landed property. The loss of their property was made permanent

in 1814 when it was rea¢ rmed by Louis XVIII (Louis XVI’s brother). Emigrés (and their

descendants) were to be compensated by the April 27, 1825, law, which came to be known as

the “milliard des émigrés” since these reparations amounted to nearly one billion French francs

(nearly 10% of the French GDP in 1825 (Maddison (2001))), but not all émigrés eventually

received comp ens ation for their losses. Overall, some of the émigrés were able to reconstitute

part of their landed estate, whereas others were only able to live a gentry life with modest means,

and some became destitute.

14

Nevertheless, there is no consensus as to who ultimately b ene …ted from the sale of the

biens nationaux. Schama (1989) suggests that the redistribution of land was not from the landed

elite to peasants, but rather a transfer of property within the landed classe s. The members of the

groups which were gaining economically before the Revolution and who managed to evade violence

13

For an overview of the successive laws pertaini ng to the sale of the biens nationaux, see Bodinier and Teyssier

(2000). For a speci…c analysis of the economic consequences of the sale of the Church property, see Finley, Franck,

and Johnson (20 17). On macroeco nomic policies during the French Re volution, see, for example, Sargent and Velde

(1995).

14

Aristocrats like the Marquis de Dr eux-Brézé in Sarth e and Barral de Montfer rat in Isère emerged …nancially

unscathed from the Revolutio n (Schama (1989 )). The Marquis de Lafayette seemed to have lost a large share of

his property and led a more modest life (Furet and Ozouf (1988)). Mme Lalanne, born Dudevant de Villeneuve,

solicited her admission to the poor house in Bordeaux (Gironde) that she had foun ded before the Revolution

(Boisnard (1992)). It must be noted that there is no evidence that the émi grés engaged in industrial and service

activities after their return; their ideological sta nce was certainly not conducive to such endeavors (Baldensperger

(1924)) .

8

by adopting a revolutionary stance (among them, many relatively wealthy urban bourgeois and

small farmers) emerged richer since they bought the landed properties of the Church and the

‡eeing landed gentry at a low price (see, e.g., Marion (1908), Cobb (1972), Sutherland (2003)).

Others argue that the sale of the biens nationaux was detrimental to the living conditions of

peasants during the 19th century because it created a small peasantry of su bsisten ce , thereby

consolidating the agrarian structure of France and delaying economic modernization (Loutchisky

(1897), Lefebvre (1924)). Finally, some contend that the redistribution of land was bene…cial to

French peasants: they became small-scale agrarian capitalists focused on market prod uc tion (Ado

(1987 [2012])). McPhee (1999), for example, provides anecdotal evidence on small landowners

who engaged in wine production in Herault.

Crucially, local monographs on the sale of the biens nationaux suggest that the eventual

extent of land redistribution and its bene…ciaries crucially depended on the extent of local em-

igration during the French Revolution. Th is is, in itself, partly to be expected since the biens

nationaux comprised the émigrés’ properties. Below, we provide examples revealing the inti-

mate relationship b etween the change in ownership structure, as a result of th e sale of the biens

nationaux in four départements, and the share of émigrés in the local population.

First, in Cher, which was the third lowest emigration département (0:11% of the popula-

tion), Marion (1908) documents that there was very little land parcelization and redistribution,

or if there was any, it bene…ted individuals who were already well o¤. For instance, in Ivoy-le-Pré

(9886 ha, 2; 438 inhabitants), not a single plot of land owned by an émigré was sold, while a

large domain was transferred from the abbey of Laurois to a major secular landowner, the local

fermier-général (a p rivate tax collector u nde r the Old Regime). Similarly, in Menetou-Râtel

(2; 801 ha, 1; 195 inhabitants), only 25 properties were sold, and 13 out of the 17 bu yers were

already major or medium-size landowners.

Second, in Gironde, which was a close-to-median intensity emigration département (0:24%

of the population), Marion (1908) shows that the prope rties owned by the Church and the

émigrés were parcelized into several smaller land lots in many rural communes, thereby enabling

individuals who were previously landless to acquire some property. For instance, in Lu gon-et-

l’Île-du-Carnay (1094 ha, 947 inhabitants), some well-known merchants and notaries bought land,

but most of the buyers of biens nationaux were landless farmers and artisans (i.e., blacksmiths,

carpenters, coopers, masons, and shoemakers), who acquired small land plots.

Third, in Nord, an above-median intensity emigration département ( 0:35% of the popu-

lation), Lefebvre (1924) provides information for 15 villages in the district of Avesnes, which we

report in Table 2. The statistics reveal that large properties were parcelized, and there was a

substantial transfer of property from nobles to peasants and urban bourgeois. Moreover, part of

9

the land, often commons, whose property was in dispute was acquired by the state, that is, either

the central government or the local towns.

Finally, in Ille-et-Vilaine, a relatively high-emigration area (0:42% of the département’s

population), many aristocrats lost a signi…cant part of their properties. The castle and the

domain of the Vaurouault family near Saint-Malo, for example, were sold as biens nationaux in

1793. The family bought back the castle at the beginning of the 19th century but pe rmanently

lost the domain to small peas ants (Boisnard (1992)). Another famous local aristocratic family

that lost some of its land was that of François-René de Chateaubriand, the romantic writer and

heir to one of the oldest baronies in Britanny. This unfortunate turn of events for François-René

de Chateaubriand’s family might explain why he was adamant later in his political career that

émigrés should b e compen sated (Chateaubriand (1847), pp. 517-533).

It is against this background that we interpret the share of émigrés in each département

as a p roxy f or the weakening of the local landed elites of the Old Regime and the extent of land

redistribution. Below, we establish the empirical validity of these claims and trace the economic

consequences of land parcelization over time.

3 Data and Empirical Methodology

3.1 Measures of Income, Workforce, and Human Capital

To capture the short- and medium-run e¤ects of emigration on income per capita at the départe-

ment level prior to World War II, we use data on GDP per capita as reconstructed by Comb es ,

Lafourcade, Thisse, and Toutain (2011) and Caruana-Galizia (2013) for 1860, 1901 and 1930.

For the post-World War II period, data on income per capita at the département level are not

available before 1995, so we use data from the French National Institute of Statistics (INSEE,

Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques) for 1995, 2000, and 2010. We also

construct the value added per worker in the agricultural, industrial, and service sec tors combining

the data of Combes, Lafourcade, Thisse, and Toutain (2011), who assess the value added in each

of thes e three sectors in 1860, 1930, 1982, and 1990, with the occupational data from the gov-

ernmental surveys carried out from the 19th century onward (Statistique Générale de la France

and INSEE). The descriptive statistics in Table D.2 indicate that the shares of the workforce in

the industrial and service sectors grew, respectively, from 21:6% and 15:3% in 1860 to 30:1% and

24:8% in 1930, indicating that slightly less than h alf of the working French population was still

engaged in agriculture before WWII. However, by 1990, the share of the agricultural workforce

had declined considerably, with the industrial and service sectors employing 30:7% and 60:0% of

the workforce, respectively.

We also explore the e¤ect of emigration during the French Revolution on the evolution of

10

human capital from the 19th century until today. For the period before World War II, we take

advantage of the data on the literacy of French army conscripts (France - Ministère de la Guerre

(1839-1937)).

15

The data enable us to compute the average share of illiterate conscripts, that is,

those who could neither read nor write, by decade between the 1840s and 1930s. Our statistics

in Table D.3 show the overall relatively high levels of literacy in France. Speci…cally, 26:7% of

French army conscripts in the 1840s, 16:0% in the 1870s, and 5:1% in the 1930s could neither read

nor write. Our post Word War II measures of human capital rely on the successive population

censuses carried out in 1968, 1975, 1982, 1990, 1999, and 2010. They allow us to compu te the

‡ow of men between the ages of 16 and 24 in each département who completed high school or

had a college degree or both.

3.2 Emigrés and Temp erature Shocks in the Summer of 1792

The observed relationship between em igration and regional development may re‡ect omitted vari-

ables which could explain both emigration and subsequent economic performance. For instance,

if emigration was proportional to the pool of “potential”émigrés, then high-emigration départe-

ments would be those with initially many nobles and many wealthy landowners. In other words,

since we do not have département-level data before and after the Revolution on the relative size

of each order (i.e., the nobility, the clergy, and the Third Estate) observed emigration rates may

be mechanically linked to the initial regional stock of the old elite and the extent of land con-

centration prior to 1789, thereby biasing ou r estimates. Moreover, despite the thorough e¤orts

to accurately reconstruct the numbers, (Greer (1951), p.17) acknowledges th at his “statistics,

cannot pretend to absolute exactitude. They include an irregular margin of error. In a few places

it may infringe as much as …fty per cent (e.g., in Var), in others it narrows to insigni…cance

(e.g., in Basses-Alpes).”

16

Another limitation of Greer (1951)’s data is that they do not provide

a yearly breakdown on the timing of emigration for each département but only for the 1789-1799

period as a whole.

To overcome these important measurement issues, we leverage the spatial variation in the

temperature shocks in the summer of 1792 as a source of variation for the share of émigrés in the

population of each département. Our identi…cation strategy is motivated by a strand of literature

documenting the e¤ect of climate on human activity and the outbreak of violence. The logic

is that abnormal weather conditions cause a tem porary decline in agricultural output, that is,

a transitory negative income shock for farming-based economies. Such a shock decreases the

15

These da ta are not subject to selection bias because every Frenchm an had to report for military service.

However, changes in consc ription rules meant that not every man eventually s erved during the 19th century

(Crépin (2009)).

16

Hi gonnet (1981) suggests, for example, that there were about 25; 000 noble émigrés inste ad of 16; 431, as

estimated by Gr eer (1951).

11

opportunity cost of violence which in our historical context can be meas ured by the intensity

of emigration rates across départements. For instance, in Orne in the west of France, a high-

emigration and high-temperature shock département in the summer of 1792, the villagers of Rai

and Corsei ransacked the Castle of Rai on Se ptemb er 23, 1792, demanding that the lord of the

manor abandon his feudal rights.

17

It is not clear when the emigration ‡ows, triggered by the events of the summer of 1792,

stopped. It is possible that emigration in some départements took place over several months

because violence continued after the summer of 1792. In this respect, two groups of regions stand

out. First, the départements of Deux-Sèvres, Loire-Inférieure, Maine-et-Loire, Morbihan, and

Vendée were the locus of the civil war in the west of France (e.g., Tilly (1964), Martin (1987)),

and second, the départements of Bouches-du-Rhône, Calvados, Gironde, and Var participated in

the Federalist Revolt in 1793 (see, e.g., Johnson (1986)). The common characteristic of these

territories was that they experienced high-temperature shocks in the summer of 1792 which

triggered a period of prolonged emigration and unrest.

In what follows, we explore the e¤ects of the di¤erential pattern of emigration during the

Revolution, which we show to be partly shaped by transitory local weather shocks in the summer

of 1792, on the long-term process of development across French départements. Our conjecture is

that emigration is likely to have had both medium- and long-run repercussions via the channels

of land redistribution and the curtailing of the upper tail of the local wealth distribution. In

this respect, it stands to reason that any direct economic impact of the summer shocks of 1792

beyond their e¤ect on emigration rates is unlikely to be quantitatively relevant several decades

after the event.

Note. In Appendix B, we o¤er two complementary pieces of evidence regarding the impact

of temperature shocks on economic conditions and lo c al violence. First, in Appendix B:1 we show

that larger temperature shocks translate into spikes in local wheat prices using data collected by

Labrousse, Romano, and Dreyfus (1970) for the 1797-1800 period which covers the latter part

of the Revolution (see Figure A.3 and columns (1)-(5) of Table D.5). Second, in Appendix B:2

we use the dataset on peasant revolts assembled by Marko¤ (1996) to quantitatively establish

that abnormal tem peratures in the summer of 1792 are systematically related to the incidence

of p eas ant revolts during the “Second Revolution”(see Figure A.1 and columns (6)-(7) of Table

D.5).

17

The lord of the m an or was Louis-Sébastien Des douits du Ray, a commoner who had been ennobled thanks to

the fortune he had m ad e when working in the Compagnie des Indes (du Mote y (1893), pp. 108-109). His children

emig rated, and years later, in 1826, he and his wife were compensated as ascendants of émigrés under the April 27,

1825, law for the property losses incur red during the French Revolutio n (France - Ministère des Finances. Etats

Déta illés des Liquidations f aites par la Commis sion d’Indemnité, à l’époque du 1er avril 1826 en Exécution de la

Loi du 27 avril 1825, Paris, De l’Imprim erie Royale, 1826. Vo l. 2, pp.2-3).

12

3.3 Temperature Shocks Construction

Our tempe rature data come from the Europ e an Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Re-

construction Project, which was developed by paleoclimatologists at the University of Berne

(Luterbacher, Dietrich, Xoplaki, Grosjean, and Wanner (2004), Luterbacher, Dietrich, Xoplaki,

Grosjean, and Wanner (2006), Pauling, Luterbacher, Casty, and Wanner (2006)). These are

season-speci…c reconstructions for the 1500-1900 period, at a resolution of 0:5 by 0:5 decimal

degrees. These data are assembled using a multiplicity of indirect proxies such as tree rings,

ice cores, corals, ocean and lake sediments, as well as historical doc ume ntary records. As such,

measurement error may be nontrivial. Moreover, climatic records are interpolated over relatively

large areas, resulting in two cells per département on average.

18

According to the authors, the

quality and breadth of the underlying sources improve over time, particularly from the end of

the 18th century onward.

We follow Hidalgo, Naidu, Nichter, and Richardson (2010) and Franck (2016) and employ

two alternative measures of temperature shocks for the summer of 1792. First, we us e the squared

deviation of temperature:

Z

d;t;s

=

x

d;t;s

x

d;s

d;s

2

;

where the temperature x

d;t;s

in département d in year t of season s is standardized by the mean

x

d;s

and the standard deviation

d;s

of temperature in each département d in season s, where

both the mean and standard deviation are computed over a baseline period. The baseline p eriod

which we use to compute x

d;s

and

d;s

comprises all the s umme r temperatures in the 25 years

before 1792 (i.e., from 1767 until 1791). As we discuss below, we consider several robustne ss

checks to this baseline speci…cation.

Second, we de…ne the absolute deviation of temperature as:

Z

d;t;s

=

x

d;t;s

x

d;s

d;s

;

Panel B of Figure 1 maps the spatial distribution of the mean temperature in the summer

of 1792, while Panel C of Figure 1 portrays the squared deviation of temperature. In Panel D

we present these temperature shocks after partialing out the time-invariant geographic controls

described below. The observed spatial variation in temperature shocks of Panel D is our source

of identi…cation.

18

Départements were designed in 1790 to be o f relatively small size so that it would take at most one day of

horse travel to reach the département ’s administr ative center from any location in the département. On aver age,

the d épartement ’s area is 6; 000 km

2

, which is approxi mate ly the size of the US state of Delaware.

13

It is important to note that the summer of 1792 was comparable to the other summers

during the Revolution. The descriptive statistics in Table D.4 indeed show that the summer of

1792 is at the median of the summer temperature distribution for the 1788-1799 period, with an

average temperature of 17:97, standard deviation 1:36, and a minimum (maximum) temperature

of 13:69 (21:82). The temperature in the summer of 1792 was therefore less unusual than the

summers of 1788 and 1789 which led to the outbreak of the Revolution. In fact, the descriptive

statistics in Table D.4 show that the average temperature shock in the summer of 1792 was milder

than any other summer temperature shock during the 1788-1799 period.

3.4 Confounding Characteristics of Each Département

3.4.1 Geographic Characteristics

In the e mpirical analysis below, we control for the département’s area, land suitability for agri-

culture, elevation, longitude and latitude. These geographic characteristics may in‡uence both a

region’s emigration rate as well as its agricultural comparative advantage and hence the pace of

industrialization and, ultimately, economic growth. Controlling for longitude and latitude also

enables us to account for the location of industries before (and after) the Revolution that were

mostly situated in the east and north of France. Moreover, given the importance of temperature

shocks in 1792 for our identi…cation strategy (see below), we control for the average temperature

in the summer of 1792. In addition, we take into account the distance from each département’s

main administrative center (chef-lieu) to the coast, the border, and the three largest urban cen-

ters (before the French Revolution and to this day), Paris, Lyon, and Marseille. These variables

capture the potential confounding e¤ects of the geographic location of the départements, which

may have a¤ected emigration intensity and local development via the proximity to trade routes.

3.4.2 Prerevolutionary Characteristics

Di¤erences in loc al pre-1789 development outcomes may have jointly a¤ected emigration during

the Revolution and the subsequent evolution of income per capita. To account for these poten-

tially confounding factors, we add the following proxies. First, to capture prerevolutionary levels

of human capital, particularly the upper end of the distribution, we use an indicator for the

presence of a university in 1700 in the département (Bosker, Buringh, and van Zanden (2013)).

Second, we compute the share of the population that subscribed to the Quarto edition of the En-

cyclopédie in the mid -18th century (Darnton (1973), Squicciarini and Voigtländer (2015)) which

also captures the di¤usion of the ideas of the Enlightenment within France. Third, we construct

the number of mechanical mills in 1789 used in textile production (Bonin and Langlois (1997)).

This variable not only accounts for early industrialization but also for prerevolutionary agita-

14

tion as a substantial number of riots in France in 1788 and 1789 occurred in textile-producing

regions that su¤ered from the increased competition from English manufacturers after the sig-

nature of the Eden Treaty in 1786 (which lowered tari¤s between England and France (Mathiez

(1922-1924))).

19

Finally, we add a dummy for the départements which Vivier (1998) singles out

as having few commons just before the outbreak of the Revolution and hence more established

private prop erty rights over land.

3.5 Empirical Model

The e¤ect of emigration during the French Revolution on economic development is estimated

using 2SLS. The second stage provides a cross-sectional estimate of the relationship between the

share of émigrés in the population in each département du ring the Revolution and measures of

GDP p er capita, human capital, and additional economic outcomes at di¤erent points in time:

Y

d;t

= + E

d

+ X

0

d

:! + "

d;t

;

where Y

d;t

represents some proxy of economic performance in département d in year t, E

d

is the

log of the share of émigrés in the population of département d, X

0

d

is a vector of geographical and

prerevolutionary characteristics of département d, and "

d;t

is an i.i.d. error term for département

d in year t.

In the …rst stage, E

d

; the log of the share of émigrés in the population of département d

during the French Revolution is instrumented by Z

d;1792

, the squared (or absolute) deviation of

temperature in the summer of 1792:

E

d

=

0

+

1

Z

d;1792

+ X

0

d

:! +

d

;

where X

0

d

is a vector of geographical and prerevolutionary traits of département d described

above.

4 Results

4.1 First Stage: Temperature Shocks in the Summer of 1792 and Emigration

The …rst-stage results are reported in Table 3 where the instrument is the squared (absolute) stan-

dardized deviation from average temperature in the summer of 1792 in columns (1)-(3) (columns

(4)-(6)). In all speci…cations and irrespective of the inclusion of geographic and historical con-

trols, the estimates reveal that the squared and absolute temperature deviations in the summer

19

On the Eden Treaty, see, for example, Henderson (1957), and on the consequences of t he disruption to interna-

tional trade caused by the revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, see, for example, Heckscher (1922), Crouzet (1964)

and Juhász (2015).

15

of 1792 are positively and signi…cantly correlated at the 1% level with variations in the share of

émigrés across French départements. Th is e¤ect is also quantitatively large. In column (3) of

Table 3, the beta coe¢ cient equals to 0:549. Put di¤erently, a one-standard-deviation increase

in the squared deviation from temperature in the summer of 1792 (0:067) increases the share of

émigrés in the population by 0:42% (relative to a sample mean of 0:47% and a standard deviation

of 0:64%). Moreover, the F-statistic of the …rst stage is equal to 16:88 in the speci…cation where

the instrumental variable is the squared deviation of temperature in 1792 (column (3)) and 11:32

in the speci…cation where the instrumental variable is the absolute deviation of temperature in

1792 (column (6)), su ggesting that these instruments are not weak. Figure 2 graphs the …rst-

stage relationship between the squared deviation from average temperature in the summer of 1792

and the share of émigrés, conditional on geographic characteristics (Panel A) and conditional on

geographic and pre-1789 historical characteristics (Panel B).

Note. In Appendix B:3, we provide a series of robustness checks on the uncovered link

between temperature shocks in the summe r of 1792 and variation in the share of émigrés. These

robustness checks have a dual goal. The …rst is to highlight that consistent with the historical

narrative, the temperature shock of the summer of 1792 is the only signi…cant determinant of

emigration among all the temp erature shocks during the revolutionary period. Speci…cally, we

show that emigration rates are not explained by (i) temperature shocks in the other three seasons

of 1792 (Table D.6); (ii) summer temperature deviations between 1788 and 1800 (Table D.7); or

(iii) rainfall shocks in the summer of 1792 (Table D.8). We also show that (iv) Conley-corrected

standard errors at various distance thresholds provide similar …rst-stage results (Table D.9); (v)

and alternative time windows to standardize the temperature shocks (Table D.10) do not change

the patterns found.

Second, in an attempt to strengthen our identi…cation assumption, namely that the weather

shock in the su mmer of 1792 is uncorrelated with preexisting social and economic traits, we

gathered salient pre-revolutionary covariates at the département level and tested whe ther these

features predict the 1792 temperature deviation. S uch c ovariates include (i) episo d es of violence

immediately before (and after) the Revolution; (ii) complaints of the French population in 1789

as expressed in the cahiers de doléances; (iii) human capital before the Revolution proxied by

the share of brides and grooms that were able to sign their wedding contracts; (iv) the share of

the clergy that was hostile to the Revolution, and (v) the number of famous aristocratic families.

All in all, the results in Table D.11 are reassuring. None of these potentially important variables

correlates with our instrument, thus suggesting that it is a plausible source of identi…cation for

the impact of emigration on regional economic performance in the short and longue durée.

16

4.2 The E¤ect of the Emigrés on the Economy in the Medium and Long Run

In this subsection, we explore the impact of emigration during the Revolution on several economic

outcomes over time, namely income per capita, sectoral labor productivity, and the composition

of the workforce.

4.2.1 Emigrés and the Evolution of Income per Capita

The relationship between emigration and income per capita up to World War II is presented in

Table 4, where the instrument is the squared deviation from standardized temperature in the

summer of 1792. Table D.12 in Append ix D replicates Table 4 using the absolute deviation

from standardized temperature in the su mmer of 1792: As shown in columns (1), (5), and (9) in

Panel A of Table 4, the unconditional OLS relationship between emigration and GDP per capita

is negative in 1860 and 1901, and turns positive in 1930 but is insigni…cant. The relationship

between emigration and income per capita in 1860 strengthens and becomes signi…cant when

we account for geographical factors in column (2). The 2SLS estimates in columns (3)-(4), (7)-

(8), and (11)-(12) in Panel A of Table 4 reveal that there is a negative and signi…cant e¤ect

of emigration on income per c apita in 1860 and 1901 as well as a negative but insigni…cant

e¤ect in 1930, whether we only account for geographic controls or include both geographic and

prehistorical controls. A half-percentage-point increase in the share of émigrés in a département

decreases GDP per capita by 12:8% in 1860 and 18:8% in 1901.

20

In both Tables 4 and D.12, the

coe¢ cient estimates associated with the share of émigrés in the 2SLS regress ions are signi…cantly

larger than the corresponding OLS ones. Besides measurement error in the share of émigrés

resulting in attenuation bias in the OLS coe¢ cients, an additional and p erhap s more pertinent

explanation for the downward bias of the OLS coe¢ cient arises from the fact that the unobserved

initial presence of wealthy landowners and priests in the p op ulation of a given département (the

stock) and their measured share in the département’s population (the ‡ow) are mechanically

linked.

An alternative way to assess the negative but eventually vanishing impact of emigration

on local economic development during the 19th and early 20th centuries can be seen in Figure

D.4 where we take advantage of the data from Bonneuil (1997) on fertility and infant mortality

between 1811 and 1901. The fertility rate is computed as the Coale fertility index (Coale (1969))

for each département, while the infant mortality rate is computed as the share of children who

20

Few of our geographic and historical contr ols a re signi…cant in the 2SLS regressions reported in columns

(8) and (12). Longitude is positively correlated with in come per capita in 1860 and 1901, probably re‡ecting

the fact that dépar tements in the east o f France were more industrialized. A lack of c ommons in the 1780s

is also positi vely correlated with income per capita, which could be expected since commons were detrimental to

ag ricultur al produ cti vity. Finally, distance to the coast has a negative impact on income, as landlocked départeme nts

could not pro…t from maritime trade.

17

died before their …rst birthday. In Figure D.4 we report the coe¢ cients associated with the share

of émigrés in 2SLS regressions (available upon request) wh ere the dependent variable is the Coale

fertility index (Panel A) and infant mortality (Panel B). A high share of émigrés has a positive

and signi…cant e¤ect on fertility an d infant mortality until the 1880s, and no signi…cant impact

afterward.

The relationship between emigration and income per capita in the long run is presented in

Panel B of Table 4. As shown in columns (1), (5) and (9) unconditionally, emigration during the

Revolution has an insigni…cant positive association with income per capita across départements in

1995, 2000, and 2010. This relationship becomes signi…cantly positive once geographical features

are accounted for in columns (2), (6), and (10). Finally, the 2SLS estimates in columns (3)-(4),

(7)-(8), and (11)-(12) in Panel B of Table 4 suggest that emigration had a positive e¤ect in the

long run. A half-percentage-point increase in emigration increases GDP per capita in 1995 by

8:7%, in 2000 by 9:8%, and in 2010 by 8:8%.

21

Similar results are reported in Table D.12 in

Appendix D.

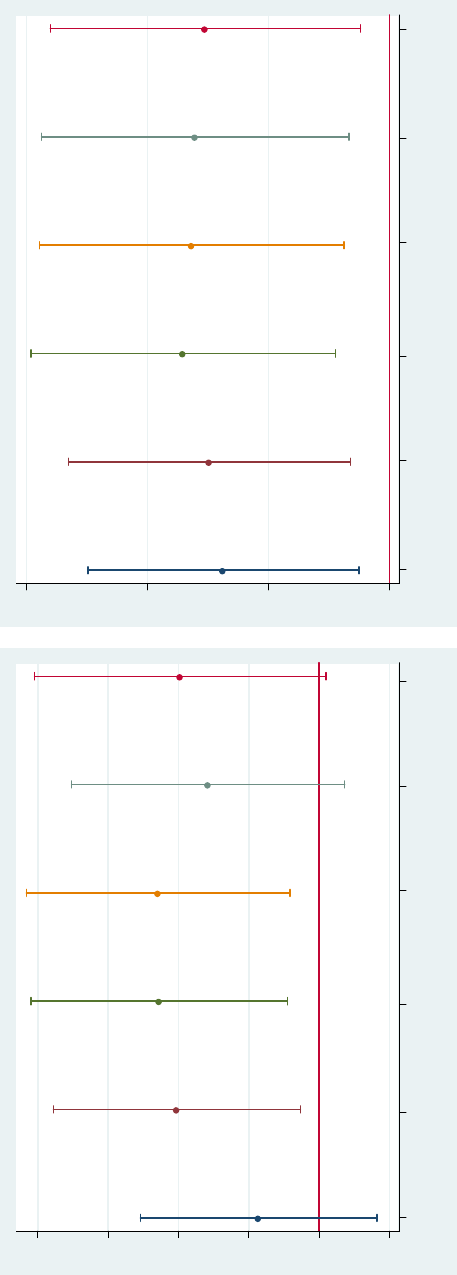

Our 2SLS estimates in Tables 4 and D.12 indicate that there was a reversal of the e¤ect of

emigration on income per capita: départements with more emigration were poorer until World

War I but became richer by the turn of the 21st century. We illustrate this reversal by plotting

in Figure 3 the coe¢ cients associated with the share of émigrés in the 2SLS regressions reported

in columns (4), (8), and (12) of Panels A and B in Tables 4 and D.12.

Robustness checks. This reversal in the impact of emigration on economic performance

is driven neither by a speci…c group of départements nor by outlier départements with “too few”

or “too many”émigrés. In Figure 4, we plot the coe¢ cients from 2SLS regressions on GDP per

capita in 1860 and 2010 where we remove one “nuts 1”region at a time.

22

In Figure 5, we plot

the coe¢ cients from 2SLS regressions on GDP per capita in 1860 and 2010, where we remove the

top and bottom 1%, 5%, 10% and 20% départements in the distribution of the share of émigrés.

Under all these alternative permutations, the coe¢ cient associated with the share of émigrés in

the 2SLS regressions remains consistently signi…cant: negative in 1860 and positive in 2010.

This pattern is also evident in the reduced-form estimates reported in Table D.7 in Appen-

dix D. Panels A and B of Figure 6 graph the reduced-form relationships between the temperature

shock in the summer of 1792 and GDP per capita in 1860 and 2010, respectively. Moreover, the

reduced-form regressions in Table D.7 in Appendix D show that no temperature shock in the

21

In the 2SLS regre ssion s, three covariate s have a systematic signi…cant e¤ect on GDP per capita in 1995, 2000,

and 2010. Speci…cally, the di stance of each département from Paris and Lyon is negatively correlated with income,

indicating the importance of these two major urb an centers on spatial d evelopment. Furth ermore we …nd that the

département ’s area is positively correla ted with income, suggesting the presence o f scale e¤ects.

22

The nomenc lature o f territorial units for statistics (or “nuts”) i s a standard fo r referencing administrative

divisions within European Union c ountries. Here we use the …rst level of “nuts” for France.

18

summers between 1788 and 1800, other than that of 1792, can explain this reversal. We also

show that the sign and statistical s igni…cance in the reduced-form relationship between tempera-

ture shocks in 1792 and GDP per capita in 1860 and 2010 is robust to using baselines other than

the 25 years preceding 1792, that is, using the 50 years before 1792 (1743-1791) or the 1751-1800,

1751-1775, and 1776-1800 periods in Table D.10 in Appendix D.

Finally, in Table D.13, we examine the impact of the social status of émigrés on GDP

per capita in 1860 and 2010 by distinguishing between rich émigrés (aristocrats, priests, and

upper middle class) and poor émigrés (lower middle class, workers, and peasants). Even though

statistics on these social groups of émigrés are only available for 69 out of 86 départements, the

2SLS regression results in Table D.13 are qualitatively similar to those in Table 4 insofar as the

shares of rich and poor émigrés have a negative and signi…cant e¤ect on GDP per capita in 1860

and a positive and signi…cant impact on GDP per capita in 2010.

4.2.2 Emigrés, Labor Productivity, and the Workforce

This subsection explores the e¤ect of emigration on labor productivity in the di¤erent sectors of

the economy. In Panel A of Table 5, we examine the impact of emigration on the value added

per worker in the agricultural, industrial, and service sectors in 1860, 1930, 1982, and 1990,

respectively. The 2SLS regressions in colum ns (1)-(3) show that emigration had a signi…cantly

negative impact on productivity in all three sectors in 1860. The estimates in columns (4)-(6)

reveal that there was still a negative e¤ect of emigration on agricultural productivity in 1930.

However, in columns (7)-(12), the e¤ect of the share of émigrés on pro du ctivity in each sector in

1982 and 1990 is pos itive and signi…cant.

The negative e¤ect of the share of émigrés on agricultural productivity in the mid-19th

century can be partially accounted for by the limited mechanization in agriculture in 1862 in high-

emigration départements. Speci…cally, in Table 6 we …nd th at, out of the 15 di¤erent categories of

agricultural instruments per worker in the agricultural sector, emigration is negatively correlated

with 13 of these inputs, and this e¤ect is signi…cant for the quantity of fertilizer and the number

of scari…ers, grubbers, searchers, seeders, and tedders. It is also signi…cantly and negatively

correlated with the …rst principal component of all these agricultural tools per worker in the

agricultural sector. These results are in line with the view that French agriculture remained

relatively backward as a result of the French Revolution.

23

In Panel B of Table 5, we examine the impact of emigration on the share of the workforce

employed in the agricultural, industrial, and service sectors. The 2SLS regressions in columns

23

In regressions available upon request, which are moti vated by the study of Rosenthal (1988) on irrigation in

the aft erma th of the Revolution, we analyze the impact of emigration during the Revolution on the area drained

in each department as wel l as the number of pipe factorie s in each département in 1856 using the information in

Barral (18 58). We …nd that emigration had an insig ni…cant impact on bo th variables.

19

(1)-(3) show that emigration had a positive but insigni…cant impact on the share of the workforce

in the agricultural sector in 1860, a positive and signi…cant e¤ect at the 10% level on the share

of the workforce in the service sector, but a negative and signi…cant e¤ect at the 1% level on the

share of the workforce in the industrial sector. This last result suggests that emigration during

the French Revolution delayed the structural transformation of France toward the industrial era,

in line with the analysis of Cobban (1962). Moreover, the regressions in columns (4)-(6) show

that in 1930, emigration still had an insigni…cant e¤ect on the share of the workforce in the

agricultural sector, a negative and signi…cant e¤ect at the 10% level on the share of the workforce

in the industrial sector, and a positive and signi…cant e¤ect at the 5% level on the share of the

workforce in the service sector. Finally, the regressions in columns (7)-(9) show that in 2010,

emigration had a negative and signi…cant e¤ect at the 1% level on the share of the workforce in

the agricultural sector as well as a positive and signi…cant e¤ect on the sh ares of the workforce

in the industrial s ector at the 5% level and in the service sector at the 1% level.

All in all, the evidence in Tables 5 and 6 sheds some light on the sources of the nega-

tive impact of emigration on incomes during the 19th century shown in Table 4. It suggests

that emigration during the French Revolution disp roportionately and inverse ly a¤ected agricul-

tural productivity up until World War II and slowe d down the structural transformation toward

industry during the 19th century. Nevertheless, since the second half of the 20th century, high-

emigration départements have been hosting a more productive workforce in the industrial and

service sectors.

24

5 Mechanisms

In this section we explore some potential channels which may account for the ne gative e¤ect of

emigration during the Revolution on the standards of living in the 19th century and its positive

e¤ect toward the end of the 20th century. First, we investigate how the absence of émigrés seems

to have had an impact on the size and the composition of the local elites during the 19th century.

Second, we analyze the impact of émigrés on the landownership structure. Finally, we examine

their e¤ect on the evolution of human capital across départements over time.

5.1 Emigration during the Revolution and the Economic Elites of the 19th

Century

Here we investigate how emigration during the Revolution in‡uenced the size and composition of

local elites during the 19th century. The 2SLS estimates in Table 7 focus on electors in the 1839

24

In Tab le D.14, we examine the impact of emigration during the Revolution on t he population in each départe-

ment (Panel A) as well as in the chef -lieu (i.e., administrati ve ce nter) of each département (Panel B). We …nd that

emig ration during the Re volution has no impact on population density until World War II.

20

elections under the regime of the July monarchy (1830-1848). At that time, the voting franchise

was restricted to men above the age of 25 who could pay 200 francs worth of direct annual taxes.

This was a signi…cant amount cons idering that th e average daily wage of bakers in Paris in 1840

was equal to four francs (Chevallier (1887), p.46).

The 2SLS estimates in column (1) of Table 7 show that émigrés had a negative e¤ect

on the share of electors in the popu lation in 1839. The presence of a smaller economic elite in

high-émigrés areas suggests that the local elites were severely weakened by emigration during

the Revolution, leaving these départements with fewer wealthy individuals who could potentially

fund the costly investments of industrialization. This …nding is in line with the evidence in Table

5, that départements with a large share of émigrés were characterized by both lower productivity

and lower employment in the industrial sector.

25

Moreover, the estimates in Table 7 suggest that emigration had a negative e¤ect on the

share of landowners among the electors (column (2)), a positive but insigni…cant e¤ect on the

share of businessmen and professionals (i.e., doctors and lawyers) (columns (3)-(4)), as well as a

positive and signi…cant e¤ect on the share of civil servants (column (5)). The …nding in column

(2) highlights the relative paucity of su¢ ciently wealthy landowners that may explain the lower

agricultural productivity in 1860 in high-emigration départements. We come back to this issue

in the next section where we d iscu ss in detail how the composition of agricultural landholdings

shaped local development.

The estimate in column (5) of Table 7 shows that in 1839, electors in high-emigration

départements were disproportionately drawn from the pool of civil servants. At …rst, this pat-

tern may seem puzzling, but it is in line with the analysis of Tocqueville (1856) on how the

French Revolution contributed to the growth of the French adminis tration and the central state.

The increased presence of civil servants in high-emigration départements is corroborated by the

estimates in Table D.16, where we show that emigration had a positive and signi…cant e¤ect

on the workforce share of civil servants in 1851 and 1866 as well as a positive but insigni…cant

one in 1881. All in all, the evidence suggests that there were relatively more civil servants, and

presumably, a more powerful administrative machine, in the départements where the Revolution

had been more intense, as proxied by the share of émigrés in the population.

25

In Tab le D.15, we examine the impact of emigrati on on local …nancial development. We proxy the latter by

the total value of loans (in Fre nch francs) granted by local savings banks and by the number of contr acts sealed

by notaries in each département, keeping in mind that notaries had, by the second half of the 19th century, lost

their central role as …nancial intermediari es which they ha d held prior to the Revolution (Ho¤man, Postel-Vinay,

and Rosenth al ( 2000)). We …nd that emigration is negatively correlated with both measures during the 19th

century ( the e¤ect is, however, only signi…cant on the number of co ntracts sealed by notaries in 1861). Overall,

the results sugge st t hat the negative e¤ect of émigrés on GDP per capita only weakly stemmed from …nancial

underdevelopment.

21

5.2 Emigration during the Revolution and the Composition of Agricultural

Holdings

We have already established that in départements with a higher share of émigrés, labor agricul-

tural productivity was signi…cantly lower and fewer rich landowners voted in the elections held

in 1839. In this section, we further examine the impact of emigration on the size of agricultural

landholdings.

In the agricultural census of 1862, landholdings are categorized in brackets according to

their size. The largest landholdings are those in the category above 40 hectares. Given the

historical account and the evidence on the composition of the elites, one would expect to …nd

that high-emigration départements have a dearth of large holdings. This is shown to be the

case in column (1) in Panel A of Table 8 where the dependent variable is the share of farms

above 40 hectares: a one-percentage-point increase in the share of émigrés in the population

decreases the share of farms above 40 hectares in 1862 by 1:54%. It is instructive to link this

…nding with the work of David (1975) (pp.221-231) on the adoption of the mechanical reaper

for harvesting wheat in 1854-1857 in the United States. He …nds that the mechanical reaper

was only economically viable for farms larger than roughly 20 hectares. In 1862 only 13% of

farms were above 20 hectares in the median French département, while 52:9% and 58:5% of farms

were above that threshold in the United States in 1860 and England in 1851 (Grigg (1992)),

respectively. Moreover, as we show in column (2), French départements that experienced a

larger exodus during the Revolution had systematically fewer farms above this scale-e¢ cient size.

Namely, we …nd that a one-percentage-point inc rease in the share of émigrés in the population

decreased the share of farms above 20 hectares in 1862 by 0:87%. This absence of su¢ ciently

large landholdings echoes the …ndings in Table 6 regarding th e delayed mechanization of French

agriculture in high-emigration départements.

In columns (3)-(5) in Panel A of Table 8, our de pendent variables are the ratio of the number

of farms of 40 hectares and above to the number of farms below 10 hectares in 1862 and the ratio

of the number of farms of 50 hectares and above to the number of farms below 10 hectares in 1929

and 2000. These variables are meant to capture the relative abundance of large- to small-sized

farms within a département. Over the last 150 years, regions in France where emigration was

more intense during the 1789 Revolution consistently feature an agricultural landscape dominated

by small- to medium-sized farmers and a scarcity of large ones.

26

The demise of large landed

elites and the creation of a small peasantry mainly working for subsistence, at least until World

War II, was part of the legacy of the émigrés’ ‡ight during the French Revolution. Panels C

and D of Figure 6 plot th e residuals of the reduced-form regressions between the summer of 1792

26

Additional results available upon request show that the share of émigrés had a positive but insigni…cant e¤ect

on the total number of farms and to tal number of farms per inhabitant in 1862.

22