1

New Mexico Child Fatality Review 2023

Report

Findings & Recommendations from Child Deaths Reviewed in 2022

Oice of Injury and Violence Prevention

Injury and Behavioral Epidemiology Bureau

Epidemiology and Response Division

New Mexico Department of Health

December 2023

2

This page intentionally left blank.

3

State of New Mexico

The Honorable Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham

New Mexico Department of Health

Patrick Allen, Cabinet Secretary

Laura Chanchien Parajón, MD, MPH, Deputy Cabinet Secretary

Epidemiology and Response Division

Laura Chanchien Parajón, MD, MPH, Acting Division Director

Heidi Krapfl, MS, Deputy Division Director of Programs

Injury and Behavioral Epidemiology Bureau

Rachel Wexler, Acting Bureau Chief

Oice of Injury and Violence Prevention

Rachel Wexler, Injury & Violence Prevention Section Manager

Rachel E. Ralya, Evaluation Unit Manager

Oluwatosin Ogunmayowa, PhD, Senior Injury Epidemiologist

Arpita Paul, MPH, MBBS, Injury Epidemiologist

4

Table of Contents

Executive Summary........................................................................................................................................ 5

Background .................................................................................................................................................... 7

Child Fatality Review .................................................................................................................................. 7

A Framework for Prevention ....................................................................................................................... 8

A Public Health Approach ....................................................................................................................... 8

Social-Ecological Model.......................................................................................................................... 9

Shared Risk and Protective Factors ........................................................................................................ 9

Social Determinants of Health ...............................................................................................................10

Adverse Childhood Experiences ............................................................................................................ 11

New Mexico Child Fatality Review ............................................................................................................. 13

Review Panels ........................................................................................................................................14

Report Narrative ............................................................................................................................................ 15

Child Death in New Mexico ........................................................................................................................ 15

Leading Causes of Child Death.............................................................................................................. 15

The Cost of Child Mortality .................................................................................................................... 17

Child Injury Death Rate .......................................................................................................................... 18

Youth Mental Health in New Mexico ..........................................................................................................19

Disparities in Youth Suicide Aempts................................................................................................... 20

Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR ........................................................................................................ 21

2023 Report ............................................................................................................................................. 24

Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ 24

Materials Reviewed............................................................................................................................... 24

Panel Reviews ....................................................................................................................................... 25

Shared Risk and Protective Factors for Child Fatality in NM .................................................................. 45

Limitations ............................................................................................................................................ 48

Conclusions .......................................................................................................................................... 48

NM-CFR Recommendations ..................................................................................................................... 49

Previous Recommendations ................................................................................................................. 49

Discussion of Recommendations ......................................................................................................... 50

Key Recommendations .......................................................................................................................... 51

Appendix .................................................................................................................................................. 52

Appendix A: Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 52

Appendix B: State of New Mexico Child Death Review Legislation ....................................................... 55

Appendix C: Glossary Terms from OMI 2021 Annual Report.................................................................... 56

Appendix D: Oice of the Medical Investigator Annual Report 2021 – Excerpt (page 44)..................... 57

Appendix E: Suicide Awareness, Prevention and Training Organizations ............................................. 58

Appendix F: New Mexico Rule for Small Numbers and Public Data Release .......................................... 59

Appendix G: Related Resources ........................................................................................................... 60

References............................................................................................................................................... 62

NM-CFR 2023 Report Tear Sheet ............................................................................................................. 64

5

Executive Summary

The New Mexico Child Fatality Review (NM-CFR) was established in 1998, with the implementation of

Title 7 of the New Mexico Administrative Code (NMAC) Chapter 4- Disease Control, Part 5, Maternal,

Fetal, Infant and Child Death Review (NMAC 7.4.5) to examine the factors that contribute to the death

of children in New Mexico (NM) (see Appendix B). All non-natural child resident deaths in NM are

subject to review by NM-CFR. Deaths due to intentional (suicides, homicides) and unintentional

injuries (drowning, suocation, motor vehicle crashes) are preventable and vary by age. These deaths

undergo a thorough review process by multidisciplinary review panels, allowing stakeholders to beer

understand the circumstances surrounding these deaths. Through the review process, panelists

identify gaps in systems, as well as risk and protective factors of child fatalities, and develop

actionable recommendations to prevent future child fatalities of similar circumstance.

The NM-CFR utilizes the National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention (NCFRP) steps to conduct

eective review meetings:

The NM-CFR 2023 Report summarizes and analyzes information about 84 unique injury-related

deaths of NM infants, toddlers, children, and youth under the age of 18, which were reviewed in 2022.

The child fatalities described in this report occurred between the years 2018 and 2022 and includes: 2

child deaths that occurred in 2018, 7 deaths that occurred in 2019, 29 deaths that occurred in 2021, 43

deaths that occurred in 2021, and 3 deaths that occurred in 2022.

This report should not be used to compare changes over time to previous CFR reports published

by the NMDOH Oice of Injury and Violence Prevention.

Such a comparison would be inaccurate

because of the overlap in year of death.

6

Report Highlights

Causes of Death

Of the 84 unique child fatalities reviewed in 2022 and analyzed in this report, the leading causes of

death were: asphyxiation (30%), bodily force or weapon (27%), unknown (20%), and motor vehicle

crashes (11%), followed by poisoning (5%), drowning (3%), and other incidents (3%).

Age, Gender and Race

Of the 84 unique child fatalities reviewed in 2022 and analyzed in this report, the age group with the

most deaths was infants under the age of one (n=35), child fatalities were markedly higher in males

(n=54) and nearly half of cases reviewed (n=41) were of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity.

Location of Death

Of the 84 unique child fatalities reviewed in 2022 and analyzed in this report, the highest number of

child deaths were found in Bernalillo County, with 23 cases (27.8%). Following that, seven cases

(8.3%) were out of Doña Ana County, and six cases (7.14%) were out of San Juan County.

Preventability

Of the 84 unique child fatalities reviewed in 2022 and analyzed in this report, NM-CFR determined

that 80% (n=67) could have been prevented, and 2% of deaths (n=2) couldn’t be prevented.

Key findings from cases reviewed can be found in the 2023 Report, beginning on page 24.

Recommendation Highlights

In response to the data provided in this report, the NM-CFR makes evidence-based recommendations

to prevent future child fatalities of similar circumstances:

• to support program operations and improve the data used for the review,

• to increase awareness of the burden of child fatality and prevention eorts,

• to increase safe home environments, and

• to increase behavioral healthcare and access to resources.

A more detailed list of prevention recommendations can be found in the NM-CFR Recommendations

section, beginning on page 49.

The NM-CFR 2023 Report Tear Sheet is a one-page summary resource at the end of this report,

beginning on page 65. For optimal use, print in color and on both sides.

7

Background

Child Fatality Review

Every year, over 37,000 children in the United States die before reaching the age of 18. The death of a

child is a great loss to family and community. One indicator of a society's general well-being is the

ability to lower child death rates.

Child fatality review is a process in which multidisciplinary teams meet to share and discuss

information collected about a child death, also referred to as case information, to understand the

circumstances around child deaths. These multidisciplinary commiees are made up of

representatives from the medical community, public health, law enforcement, child protective

services, the oice of the coroner/medical examiner, and the prosecuting aorney's oice.

Local, regional, and state teams throughout the United States and its territories then submit this

information to the National Fatality Review Case Reporting System, a database managed by the

National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention

(NCFRP).

The Child Fatality Review process aims to:

• Identify risk and preventable causes of illness or injury

• Develop actionable recommendations to prevent child death

• Disseminate findings and recommendations to partners in prevention

The information included in this report is accessed from the New Mexico Department of Health

(NMDOH) BVRHS and from the NCFRP National Fatality Review Case Reporting System database,

which is funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services. The state, regional, and local

governments, healthcare providers, child-serving and educational groups, communities, and families

can use this information to guide decisions to make their communities safer and prevent further child

fatalities.

8

A Framework for Prevention

A Public Health Approach

Public health is “the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health

through the organized eorts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private

communities, and individuals.” — CEA Winslow

Public health is focused on improving health outcomes for entire populations. It is a science which

draws on an evidence-base informed by numerous disciplines, including medicine, epidemiology,

social sciences, education, and economics. The New Mexico Department of Health uses a public

health approach to 1) Define and Monitor the Problem, 2) Identify Risk and Protective Factors 3)

Develop and Test Prevention Strategies and 4) Assure Widespread Adoption.

Similarly, this public health approach to prevent child fatalities seeks to improve the health and

wellbeing of all children under 18 years of age. As part of this approach, NM-CFR conducts a review

process to identify factors which increase or decrease the risk of injury or violent victimization, also

called risk and protective factors. Based on this review, prevention strategies are developed through

the recommendation process.

Figure 1. The Public Health Approach

9

Social-Ecological Model

The Social-Ecological Model (SEM) considers the dynamic interplay of factors which influence health

at and across multiple levels of society- individual, relationship, community, and societal.

To improve health outcomes and to remove the burden of child fatalities, risk and protective factors

are identified at each level of the SEM. Findings and recommendations are developed for each case,

considering unique characteristics at each level of the SEM.

Shared Risk and Protective Factors

Shared Risk and Protective Factors (SRPF) is a term used in public health to acknowledge factors

which either increase or decrease interconnected risks of injury. These risk and protective factors

may occur at any singular or on multiple levels of the Social-Ecological Model.

Figure 2. The Social-Ecological Model

10

Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the non-medical factors that have impacts on health

outcomes and contribute to a wide range of health disparities (CDC, 2023). SDOH play a crucial role in

influencing the overall health and well-being of individuals, regardless of their age.

However, it is especially crucial to consider the influence of SDOH on children and youth. This is

because the physical, social, and emotional abilities that develop during early life serve as the

building blocks for long-term health and well-being throughout the lifespan. Health disparities exist in

the population of NM among dierent racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups due to inequitable

dierences in SDOH.

Source: Healthy people 2030, US department of Health and Human Services

The NM-CFR considers various interconnected factors operating at dierent levels during case

reviews. These factors encompass educational aainment, economic stability, social and community

dynamics, neighborhood characteristics, access to healthcare, and policy influences.

Figure 3. Social Determinants of Health

11

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) refer to potentially traumatic events that take place during

childhood (ages 0-17 years). Neighborhoods lacking resources or experiencing racial segregation

have the potential to induce stress which compounds the eect of ACEs on the development of

children's brains, immune systems, and stress-response systems. ACEs also disrupt a child’s ability to

develop healthy aention spans, decision-making processes, and ability to learn, while increasing the

risk of injury-related deaths (CDC, 2023), and the risk of future violence victimization and/or

perpetration.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) categorizes ten ACEs into three groups:

abuse, neglect, and household challenges (CDC, 2021). The ten ACEs are:

• Abuse

o Emotional abuse: A parent, stepparent, or adult living in your home swore at you,

insulted you, put you down, or acted in a way that made you afraid that you might be

physically hurt.

o Physical abuse: A parent, stepparent, or adult living in your home pushed, grabbed,

slapped, threw something at you, or hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured.

o Sexual abuse: An adult, relative, family friend, or stranger who was at least 5 years

older than you ever touched or fondled your body in a sexual way, made you touch

his/her body in a sexual way, aempted to have any type of sexual intercourse with

you.

• Household Challenges

o Mother treated violently: Your mother or stepmother was pushed, grabbed, slapped,

had something thrown at her, kicked, bien, hit with a fist, hit with something hard,

repeatedly hit for over at least a few minutes, or ever threatened or hurt by a knife or

gun by your father (or stepfather) or mother’s boyfriend.

o Substance abuse in the household: A household member with excessive use of

psychoactive drugs, such as alcohol, pain medications, or illegal drugs that can lead to

physical, social or emotional harm.

o Mental illness in the household: A household member was depressed or mentally ill or

a household member aempted suicide.

o Parental separation or divorce: Your parents were ever separated or divorced.

o Incarcerated household member: A household member went to prison.

•

Neglect

o

Emotional neglect: Someone in your family never or rarely helped you feel important or

special, you never or rarely felt loved, people in your family never or rarely looked out for

each other and felt close to each other, or your family was never or rarely a source of

strength and support.

o

Physical neglect: There was never or rarely someone to take care of you, protect you,

or take you to the doctor if you needed it, you didn’t have enough to eat, your parents

were too drunk or too high to take care of you, or you had to wear dirty clothes.

12

Emerging research about additional circumstances experienced in childhood which may increase

adversity:

• Housing insecurity

o Emerging research suggests that adults who have experienced housing insecurity are

significantly more likely to have encountered adverse experiences during their

childhood compared to individuals in the general population who have not experienced

housing insecurity (Curry, 2017).

• Community violence

o Experiencing community violence and physical abuse during childhood can have a

significant impact on both externalizing behaviors and academic performance in later

years. Furthermore, it is crucial to acknowledge that community violence exposure

(CVE) has a distinct and autonomous eect when evaluating the influence of physical

abuse (Schneider, 2020).

ACEs and the detrimental eects they cause can be reduced through preventive measures. The

establishment and maintenance of secure, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments for

children and families can eectively mitigate ACEs and reduce the occurrence of child fatalities. In

2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a resource guide about ACEs

,

highlighting six strategies to prevent ACEs:

1. S

trengthen Economic Supports for Families;

2. Promote Social Norms that Protect Against Violence and Adversity;

3. Ensure a Strong Start for Children;

4. Teach Skills;

5. Connect Youth to Caring Adults and Activities;

6. Intervene to Lessen Immediate and Long-term Harms.

Essentials for Childhood: Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences through Data to Action i

s a CDC

funded program focused on preventing ACEs and promoting positive childhood experiences (PCEs).

Twelve recipient organizations across the nation are building or improving ACEs and PCEs data

collection infrastructure and capacity, implementing and sustaining ACEs prevention strategies,

focusing on health equity and conducting ongoing data-to-action activities to inform changes to

their existing prevention strategies or select additional strategies.

13

New Mexico Child Fatality Review

Title 7 of the New Mexico Administrative Code (NMAC) Chapter 4- Disease Control, Part 5, Maternal,

Fetal, Infant and Child Death Review (NMAC 7.4.5) to examine the factors that contribute to the death

of children in NM (see Appendix B).

The NM-CFR employs a confidential, comprehensive approach, incorporating both qualitative and

quantitative data related to non-natural child deaths, which includes accidental deaths, homicides by

parent or caregiver, suicides, and cases where the cause of death cannot be determined. Homicides

by a person other than a parent or caregiver are excluded from review. All non-natural child deaths in

NM are subject to review by NM-CFR. The objective of this approach is to improve understanding of

the complex variables associated with child fatalities in the state of New Mexico.

These deaths undergo a thorough review process by multidisciplinary review panels, allowing

stakeholders to beer understand the circumstances surrounding these deaths. Through the review

process, panelists identify gaps in systems, as well as risk and protective factors of child fatalities,

and develop actionable recommendations to prevent future child fatalities of similar circumstance.

The review process can also alert communities and policy makers about emerging trends in

circumstances surrounding intentional and unintentional injuries which contribute to child deaths.

For more than 20 years, NM-CFR has been providing prevention recommendations. While some of the

recommendations led to enacted legislation, many of the recommendations were adopted by state

agencies and community partners. NM-CFR reports from previous years may be found at

www.nmhealth.org

.

Standard definitions of fatality-related terms, including manner of death (Appendix C), provided in

the New Mexico Oice of the Medical Investigator 2021 Annual Report

, describe data points that are

referred to in the death certification processes and used by NM-CFR (Appendix D). The New Mexico

Rule for Small Numbers and Public Data Release (Appendix F) guides the suppression of specific data

in this report as necessary.

14

Review Panels

In 2022, NM-CFR maintained four distinct case review panels. Each panel is comprised of a diverse

group of experts in child safety, public health, education, behavioral health, medicine, forensic

pathology, law enforcement, public safety, juvenile and criminal justice, and other related fields.

Child Abuse, Neglect

or Homicide (CAN-H)

This panel reviews child fatalities that result from

parent/caregiver abuse, neglect or homicide.

Sudden Unexpected

Infant Death (SUID)

This panel reviews unexpected deaths of infants less than one

year old in which the cause was not obvious before investigation.

Unintentional Injury

This panel reviews child fatalities in which the manner of death

was accidental or undetermined. The causes of death are varied

and include motor vehicle crashes, drownings, unintentional

overdose or poisonings, fire or environmentally related, and other

unintentional injuries.

Youth Suicide

This panel reviews intentional deaths among children and youth

that result from self-injury.

15

Report Narrative

This report analyzes characteristics of child fatalities reviewed in calendar year 2022. A supplemental

analysis of cases reviewed by death year(s) is presented in Figures 7, 8 and 9.

This report aims to provide information about child fatality in NM, and to promote the widespread

adoption of prevention strategies and recommendations by the NM-CFR. Its primary goal is to

advocate for the widespread implementation of prevention strategies and recommendations

endorsed by the NM-CFR. The collaborative expertise of multidisciplinary panels enhances the

likelihood of formulating pertinent and influential recommendations, ultimately influencing health

outcomes within this demographic.

Child Death in New Mexico

Leading Causes of Child Death

The following tables present the primary cause of child mortality in New Mexico from 2011 to 2021.

These data represent all child fatalities in NM, including both those due to natural causes and non-

natural causes. The table shows that unintentional injury (also referred to as accidents) consistently

ranked as the foremost cause of death during this period. Suicide and homicide have been identified

as the fourth and fifth leading causes of death in children 0-17 years of age over the course of these

years. Upon analysis across various age groups, it was discovered that injury-related deaths

consistently ranked among the leading five causes of death for children.

Table 1. Leading Causes of Child Deaths in New Mexico, 2011-2021

Leading Cause-

Children 0-17 Years

of Age

Number of Deaths

Crude rate per

100,000

population

Percentage of all

Child Deaths in

NM

Unintentional Injury

589

10.82

35.5%

Congenital Anomalies

432

7.94

26.0%

Short Gestation

276

5.07

16.6%

Suicide

231

4.24

13.9%

Homicide

133

2.81

8.0%

Source: WISQARS™ — Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (Last accessed: December 7,

2023)

Analysis of the causes of all childhood deaths in NM from year 2011 to 2021 found that unintentional

injuries were the top cause of death across multiple age groups (1 to 4 years, 5 to 9 years, 10 to 14

years, and 15 to 17 years) and the third leading cause of death in infancy (less than one year of age).

Suicide was found to be the second leading cause of death in 10 to 14 years and 15 to 17 years age

group. Homicide was the third leading cause of death in 1 to 4 years, 5 to 9 years, and 15 to 17 years

age groups. In the 5 to 9 years age group, Homicide and congenital anomalies both ranked in the

16

same position. Homicide was also found to be the fourth leading cause of death in the 10 to 14 years

age group (Table 2).

Table 2. Leading Causes of Death and Percentage by Age Group in New Mexico, 2011-2021

Leading

cause of

Death

<1 year

1 to 4 years

5 to 9 years

10 to 14 years

15 to 17 years

1

Congenital

Anomalies

39.7%

Unintentional

Injury

59.0%

Unintentional

Injury

50.6%

Unintentional

Injury

36.5%

Unintentional

Injury

40.4%

2

Short

Gestation

31.4%

Congenital

Anomalies

14.5%

Malignant

Neoplasms

18.2%

Suicide

33.3%

Suicide

37.3%

3

Unintentional

Injury

12.5%

Homicide

13.3%

Homicide

*

Malignant

Neoplasms

13.1%

Homicide

13.9%

4

Maternal

Pregnancy

Complication

s

9.3%

Malignant

Neoplasms

*

Congenital

Anomalies

*

Homicide

9.5%

Malignant

Neoplasms

*

5

Placenta Cord

Membranes

7.1%

Influenza &

Pneumonia

*

Chronic Low.

Respiratory

Disease &

Septicemia

*

Congenital

Anomalies

*

Congenital

Anomalies

*

U Unintentional Injury ry Suicide Homicide

Non-injury Deaths

Source: WISQARS™ — Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System Last accessed: December 7,

2023

* Indicates suppressed values (Small Numbers Rule, Appendix F)

17

The Cost of Child Mortality

Injury-related fatalities not only carry an immeasurable impact on individuals, families, and society,

but they also generate economic impacts. The expenses associated with injury-related fatalities

encompass medical expenditures linked to deaths caused by injuries and the value of statistical life,

which is a monetary assessment of the overall value individuals place on reducing the risk of mortality.

Value of statistical life represents the ratio of financial considerations to the risk of death. It functions

as an indicator that assesses the marginal cost of improving safety and the population's readiness to

pay for preventive and risk reductive measures. The values displayed in Table 3 are estimates based

on the age of the child at time of death. For individuals aged 0-17 years, the assigned value was 16.9

million U.S. dollars, which was derived by adjusting the estimate based on life expectancy and

baseline quality of life among population (CDC, 2021).

Table 3. Fatal Injuries in Children and Associated Cost in New Mexico, 2021

Year

Number of

Injury related

deaths (0 to

17 years)

Total

Medical

Costs

Total Value of

Statistical Life

Total

Combine

d cost

2018

97

$906,009

$1.78 B

$1.78 B

2019

102

$865,081

$1.87 B

$1.87 B

2020

85

$837,323

$1.56 B

$1.56 B

2021

110

$1.34 M

$2.01 B

$2.01 B

Source: WISQARS™ — Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System Last accessed: December 7,

2023

While value of statistical life estimates the economic burden of premature death, there is no manner

to quantify the social, psychological, and emotional impacts of the loss of a child’s life on their family,

friends and community. NM-CFR acknowledges that a statistical life estimate does not represent the

complete value of the lives lived.

18

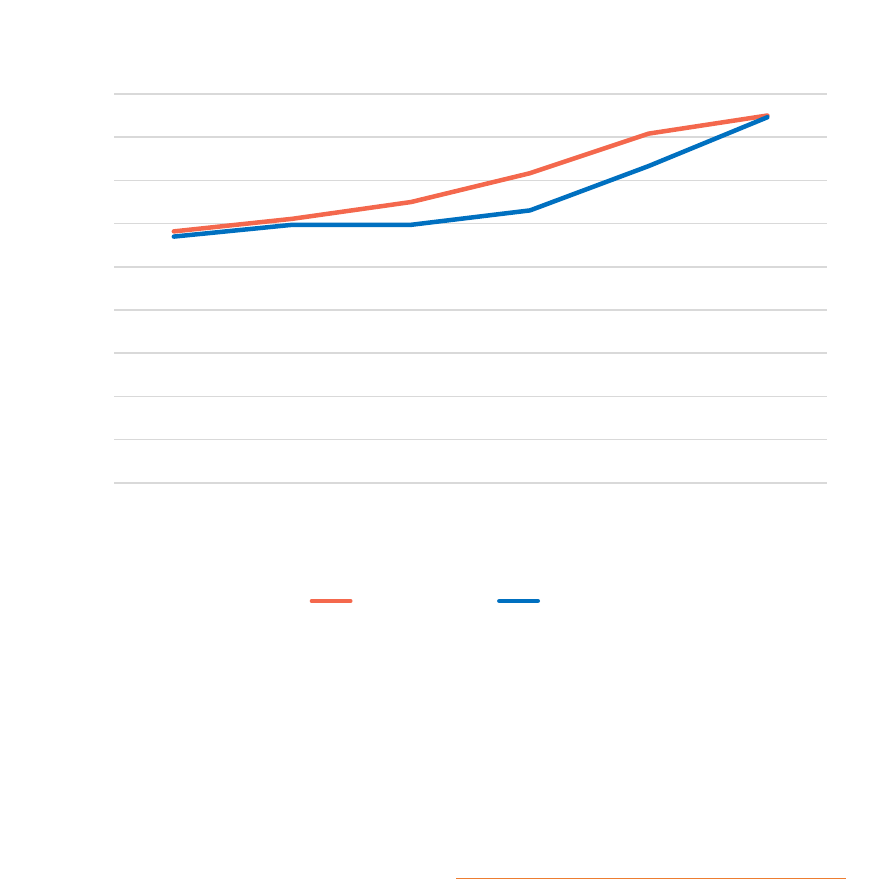

Child Injury Death Rate

The child injury death rate in NM has consistently been higher than the national rate. Figure 4 shows

that the child injury-related death rate in NM was 16.2 per 100,000 population in 2011, while the US

rate was 11.8 per 100,000 population. In 2021, the injury related death rate was 23 per 100,000

population in NM compared to 14.4 per 100,000 population in the US.

Source: CDC WONDER, Last accessed: October 17, 2023

The percentage difference in rates between NM and the US for child injury related deaths was 37.8%

in 2011, and it increased to 59.7% in 2021. From 2011 to 2021, a 41% increase was observed for child

injury-related deaths in NM.

11.8

14.4

16.2

23

0

5

10

15

20

25

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Crude rate per 100,000 population

Year

US New Mexico

+41% NM

(2011-2021)

2011

NM vs. U.S.

crude rate:

+37.8%

2021

NM vs. U.S.

crude rate:

+59.7%

Figure 4. Crude Rate (per 100,000 population) for All Injury-related Fatalities for Children (ages 0-17) in

New Mexico and the United States, 2011-2021

19

Youth Mental Health in New Mexico

According to data captured by the NM Youth Risk & Resiliency Survey (YRRS), in 2021, two out of five

NM high school students and three out of five NM female high school students experienced

persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, an overall increase of 44% since 2011 (YRRS). Figure 5

illustrates an increase in feelings of persistent sadness or hopelessness in New Mexican high

schoolers compared to the national average from 2011 to 2021.

Source: 2011-2021 NMYRRS (NMDOH); and 2011-2021 National YRBS (CDC)

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for 10 to 14-year-olds and the third leading cause of

death among individuals between the ages of 15 to 24 years in the United States (CDC, 2023).

In 2021, the Surgeon General, Vivek Murphy, issued a health advisory on youth mental health, writing,

“ensuring healthy children and families will take an all-of-society eort, including policy, institutional,

and individual changes in how we view and prioritize mental health.

29%

42%

28%

42%

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021

% Percent

Persistently Felt Sad or Hopeless

New Mexico US

Figure 5. Persistently Felt Sad or Hopeless, Grades 9-12, New Mexico, and United States

20

Disparities in Youth Suicide Aempts

Risk for suicide aempts was highest among transgender, genderqueer, genderfluid students as well

as students identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or questioning. American Indian or Alaska Native high

school students were 56% more likely to have aempted suicide than White peers (Figure 6).

Error Bar indicates 95% confidence interval.

Source: 2021 NMYRRS

14%

7%

14%

12%

13%

10%

8.7%

9%

31%

8%

21%

10%

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

Female

Male

American Indian or Alaska Native

Asian or Pacific Islander

Black or African American

Hispanic

White

Other Gender

Transgender, Genderqueer, or Genderfluid

Other Sexual Orientation

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, or Questioning

Total

Sex Race/Ethnicity

Gender

Identity

Sexual

Orientation Total

% of Suicide attempts

Figure 6. Percent of High School Students Who Aempted Suicide, by Demographics, 2021

21

Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR

Figure 7 indicates the distribution of manner of death in the reviewed cases of injury-related deaths

among children aged 0-17 years in NM, from 2005 to 2022. Most deaths which were reviewed by NM-

CFR were due to unintentional injury, followed by suicide, undetermined deaths, homicide, natural,

and deaths with unknown

1

causes.

Source: N CF RP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

1

For the purpose of this analysis, “undetermined” cases are a classification by the Oice of the Medical Investigator, where

the cause of death was not able to be determined, whereas unknown cases are those in which there was limited information

or a null value.

Figure 7. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR, by Manner of Death in New Mexico, 2005- 2022

Unknown, 3%

22

By count, the highest number of cases reviewed by NM-CFR in 2022 were from Bernalillo County

(n=318), followed by San Juan County (n=100), McKinley County (n=80), Doña Ana County (n=76),

and Sandoval County (n=71) (Figure 8).

Source: N CF RP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

Figure 8. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR, by County in New Mexico, 2005-2022

23

The distribution of child fatalities (0 to 17 years) by county was analyzed for calendar year 2021 using

a crude rate. A crude rate is the number of cases (or deaths) occurring in a specified population per

year, usually expressed as the number of cases per 100,000 population at risk. Sierra County

exhibited the highest child fatality rate (11.1), followed by Quay (5.6), Sandoval (3.3), Torrence (3.2),

Otero (3.2), Curry (3.0), and Luna (2.9) county (Figure 9).

Source: NM Bureau of Vital Records and Health Statistics,

& New Mexico's Health Indicator Data & Statistics (last accessed: November 29, 2023)

Figure 9. Crude Rate of Child Fatalities, by County in New Mexico, 2021

24

2023 Report

Methodology

In 2022, 84 unique cases were reviewed by NM-CFR across its four panels. The NM-CFR 2023 Report

summarizes and analyzes information about these 84 injury-related deaths of NM infants, toddlers,

children, and youth under the age of 18. The report covers child fatalities resulting from injuries that

occurred between the years 2018 and 2022. Each fatality was carefully reviewed in the calendar year

2022.

The data presented in this report are descriptive and not inferential. No analysis was carried out to

determine correlations or associations between variables.

This report should not be used to compare changes over time to previous CFR reports published

by the NMDOH Oice of Injury and Violence Prevention.

Such a comparison would be inaccurate

because of the overlap in year of death.

Materials Reviewed

Cases are prepared for review when NM BVRHS sends death certificates of individuals under 18 years

of age who meet the criteria for inclusion into one of the review panels to the Oice of Injury and

Violence Prevention. If the child was born in NM, the birth certificate is also provided. The NM Oice of

the Medical Investigator (OMI)’s database is then utilized to obtain death summaries, any death

investigation notes, and any available autopsy and examination notes.

Documents providing context for the circumstances leading up to and involving the child’s death may

be gathered. Additional documents may include, but are not limited to state, local, and/or federal law

enforcement records, medical records, court records, school records, obituaries, news media, and

social media posts. To supplement the records gathered for the review, panelists from the NM

Children, Youth and Families Department (CYFD) and Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act

(CARA) Program aend panel meetings and are available to provide additional information on the

child and family’s social history, as well as circumstances around the death.

25

Panel Reviews

From January 1, 2022, through December 31, 2022, 84 unique child deaths were reviewed. The child

fatalities reviewed in 2022 comprised deaths that occurred from 2018 to 2022 (Table 4). While an

eort is made to review cases in a timely fashion, not all cases receive data in a timely manner. Some

cases are criminally prosecuted, and adjudication may be desired by the panel prior to review. For

these reasons, some cases are not reviewed until these criteria are met, which may be some years

later.

Table 4. Cases Reviewed by NM-CFR, by Year of Death in New Mexico, 2022

Year of Death

Number of reviewed cases

2018

2

2019

7

2020

29

2021

43

2022

3

Each of the 84 unique child deaths were reviewed by at least one of the four panels (Table 5).

Occasionally, some child death cases received a second review to gain additional perspective from

another panel, which yielded a total of 87 reviews in calendar year 2022. Database entry for the

reviewed cases was also completed in the National Fatality Review Case Reporting System.

Table 5. Cases Reviewed by NM-CFR, by Primary Panel of Review in New Mexico, 2022

Review Panel

Frequency

Percent

Child Abuse, Neglect or Homicide

12

13.8%

Sudden Unexpected Infant Death

35

40.2%

Youth Suicide

16

18.4%

Unintentional Injury

24

27.6%

Total

87

100%

26

Most Child Deaths Are Preventable

According to the National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention (NCFRP), a child's death is

considered preventable if there was a reasonable opportunity for an individual or the community to

take action that could have altered the circumstances leading to the child's death. Figure 10 shows

that out of 84 unique child fatalities analyzed in this report, NM-CFR determined that 67 deaths

(80%) could have been prevented, and 2 deaths (2%) couldn’t be prevented. In ten cases, there was

not information about preventability (12%), and NM-CFR could not determine from the information

gathered whether the child’s death was preventable in five cases (6%).

To determine preventability, NM-CFR panelists review all available information about a child fatality.

Circumstantial information about each case is carefully reviewed, and a robust discussion about risk

and protective factors informs the determination of preventability. Each panelist determines if a case

was able or unable to be prevented, and the final determination is determined by poll.

80%

2%

6%

12%

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Yes No Undetermined Unknown

% Child Fatalities

Preventability

Figure 10. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR by Preventability in New Mexico, 2022

Source: NCFRP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

27

Figure 12. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR, by Witness Distribution in New Mexico, 2022

Of the cases reviewed by NM-CFR in 2022, autopsies were performed on 63 (75%) cases. Panelists

agreed with the primary cause of death listed on the death certificate and pathology report on 72

(86%) cases. Out of the reviewed cases, a total of 71 investigations (85%) were carried out involving

deaths. Furthermore, in 61 cases (73%), the investigation was completed at the location where the

child's death took place. The local emergency number or 911 was called in 79 (94%) of the child

deaths. Out of the child deaths reviewed, resuscitation was attempted in 54 cases, accounting for

64% of the total; in 31 (57%), of these cases, the resuscitation was attempted by parents,

bystanders, friends, or other individuals before emergency medical services (EMS) arrived at the

scene (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Review Summary of Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR, in New Mexico, 2022

Source: NCFRP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

Source: N CF RP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

9

4

3

2

1

0 2 4 6 8 10

Parent

Acquiantances

Stranger

Other

Caretaker/Babysitter

# Child Fatlities

Witness

28

The distribution of witnesses in the cases that were reviewed by NM-CFR is shown in Figure 12. A

witness to the incident was available at 16 (19%) of the cases reviewed. Among all cases witnessed,

most common witnesses at the child’s scene of death were a parent (n=9, 56.3%), followed by non-

relative/acquaintances (n=4, 25%), stranger (n=3, 18.8%), caretaker/babysier (n=2, 12.5%) and

other (n=1, 6.3%).

Source: N CF RP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

The report analyzed a total of 84 cases and found that the circumstances of the children's deaths

varied in terms of location. The child's home was the most frequent location for children's deaths,

accounting for 59 cases (70%). The second most common location was on or near a roadway, with

nine cases (11%) The other location of 32 cases (38%) where incidents occurred included: driveway,

other recreational location, other parking area, shed behind a residential home, hotel room, RV trailer,

and at another person’s home (Figure 13).

70%

11%

38%

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Home Road Other

% Child Fatalities

Incident place

Figure 13. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR, by Incident Places in New Mexico, 2022

29

Case Demographic Information

To investigate the distribution and occurrence of these child fatalities, the demographic information

of the cases, including age, gender, location, race, and ethnicity were also analyzed.

Child fatalities were higher in males (n=54, 64%) than females (n=30, 36%), as shown in Figure 14.

The only gender information available for case review was derived from death certificates, which does

not denote gender identity of the cases, a limitation of case review.

Male

Female

Source: N CF RP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

Figure 14. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR by Gender in New Mexico, 2022

36

64

30

Source: N CF RP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

Figure 15 illustrates the paern of males outnumbering females distributed across the dierent age

categories. The age group with the most deaths was infants under the age of one (n=35, 41.6%). This

was followed by age group 15 to 17 (n=26, 30.9%), then age group 10 to 14 (n=10, 11.9%), age group 1

to 4 (n=7, 8.3%) and then age group 5 to 9 (n=6, 7.1%).

17

3

4

1

5

18

4

2

9

21

0

5

10

15

20

25

less than 1 1 to 4 5 to 9 10 to 14 15 to 17

# Child Fatalities

Age Group

Female Male

Figure 15. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR, by Age and Gender in New Mexico, 2022

31

Source: N CF RP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

Analysis of race and ethnic categorical distribution of reviewed cases found that 41 (49.4%) cases

were of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Twenty-five (30.1%) cases were non-Hispanic/Latino White.

Twelve (14.4%) cases were American Indian or Alaskan Native, four (4.8%) cases were Black or African

American, and one (1.2%) case was Asian or Pacific Islander (Figure 16).

The analysis also examined the location of death of cases reviewed in 2022, by county, to explore the

distribution of cases across NM. Of the cases reviewed in 2022, the highest number of child deaths

were found in Bernalillo County, with 23 cases (27.8%). Following that, seven cases (8.3%) were out

of Doña Ana County, and six cases (7.14%) were out of San Juan County.

12

1

4

25

41

1

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

American

Indian or

Alaskan

Native

Asian/Pacific

Islander or

Native HI

Black White Hispanic/

Latino

Unknown

# Child Fatalities

Race/Ethnicity

Figure 16. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR, by Race and Ethnicity in New Mexico, 2022

32

Manner of Death

The NM-CFR reviewed the manner of death, the way in which a death occurs, across dierent

demographics. The most common manner of child death reviewed by the NM-CFR in 2022 was

unintentional injury (classified as accidental by the OMI) accounting for 39 cases (46%). This was

followed by suicide with 16 cases (19%), homicide with 12 cases (14%), undetermined with 14 cases

(17%), and natural causes with three cases (4%) (Figure 17).

Source: N CF R P, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

Figure 17. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR, by Manner of Death in New Mexico, 2022

Natural, 4%

33

An analysis of cases reviewed in 2022 by manner of death and gender (Figure 18) illustrates that most

cases reviewed, across various manners, were male. Twenty-six (30.9%) male children died by

accident compared to the female death count of 13 (15.5%). The number of male suicides (n=15,

17.8%) was significantly greater than that of females (n=1, 1.2%). In cases of homicide, the number of

male fatalities (n=7, 8.3%) was found to be higher compared to the number of female fatalities (n=5,

5.9%).

Source: N CF R P, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

2

13

1

5

9

1

26

15

7

5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Natural Accident Suicide Homicide Undetermined

# Child Fatalities

Manner of Death

Female Male

Figure 18. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR, by Manner of Death and Gender in New Mexico, 2022

34

Figure 19. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR, by Manner of Death and Age in New Mexico, 2022

Among 84 unique cases reviewed, the most frequent manner found was unintentional, which was

present in all age groups. The unintentional death count was highest for infants, accounting for 17

cases (20.2%), followed by the 15 to 18 age group with 12 cases (14.3%). Suicide was highest in the 15

to 18 age group with nine cases (10.7%) followed by the 10 to 14 age group with seven cases (8.3%).

Homicide was greatest in the 15 to 18 age group, with five cases (5.9%) (Figure 19).

Source: N CF RP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

3

17

5

3

2

12

7

9

2

2

2

1

5

13

1

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

less than 1 1 to 4 5 to 9 10 to 14 15 to 17

# Child Fatalities

Age Group

Natural Unintentional Suicide Homicide Undetermined

35

Figure 20 illustrates the causes and manners of death for cases reviewed in 2022. Of the 39

unintentional injury deaths, asphyxia was the leading cause, accounting for 18 deaths (21.4%). This

was followed by motor vehicle-related incidents, which caused nine deaths (10.7%). Other causes of

death included poisoning (n=4, 4.8%), drowning (n=3, 3.6%), and various other or unclassified

causes (n=1, 1.2%). Additionally, there was one death each resulting from fall/crush,

fire/burn/electrical incidents, and bodily force or weapon use, each accounting for 1.2% of the total

deaths. Of the 16 suicide cases, nine (10.7%) were aributed to bodily force or weapon, while seven

(8.3%) were classified as asphyxia.

Source: N CF R P, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

1

9

1

3

18

1

1

4

1

7

9

3

12

13

1

0 10 20 30

Unknown

Motor Vehicle

Fire, burn or electrocution

Drowning

Asphyxia

Bodily force or weapon

Fall or crush

Poisoning, overdose or acute intox

Other

# Child Fatalities

Causes of Death

Unintentional Suicide Natural Homicide Undetermined

Figure 20. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR, by Cause and Manner of Death in New Mexico, 2022

36

Child Abuse, Neglect or Homicide (CAN-H)

In 2022, 12 child fatalities were reviewed by the CAN-H Panel, each of which was a unique case. Of the

12 cases of child abuse, neglect, or homicide included in this report, eight (66.7%) were males, and

four (33.3%) were female. Eight (66.7%) of the children were Hispanic or Latino, three (25%) children

were White, one (8.3%) child was Black or African American. Out of 12 cases reviewed in this panel, six

cases (50%) were reported in the age group of 15 to 17 years. There were two cases (16.6%) each in

the age group of one to four years and five to nine years. Additionally, there was one case (8.3%) in

each age group of less than one year and 10 to 14 years (Figure 21).

Source: N CF R P, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

Gender

Age

Race & E t h n ic it y

4

8

1

2 2

1

6

1

3

8

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

# Child Fatalities

Age

Race & Ethnicity

Gender

Figure 21. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR (CAN-H panel) by Demographics in New Mexico, 2022

37

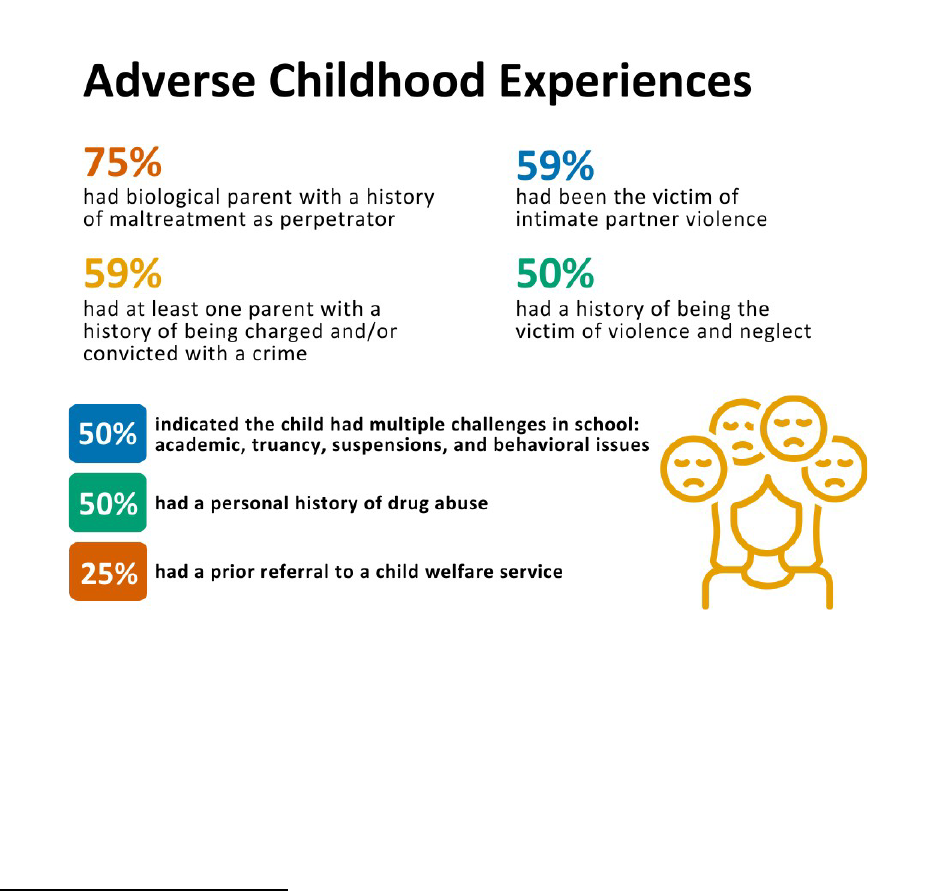

Of the 12 child fatality cases reviewed in CAN-H panel in 2022, 75% (n= 9) were identified as

having a history of maltreatment with a parent as a perpetrator. A quarter of children (n=3,

25%) had a prior referral to child welfare services. More than half of the children (n=7, 59%)

had at least one parent with a history of being charged and/or convicted of a crime.

Half of the children (n=6, 50%) had a history of victimization of violence or neglect, had a

personal history of substance misuse, or faced multiple challenges in school such as

academics, truancy, suspensions, or behavioral issues. Seven (59%) children were also

victims of intimate partner violence (Figure 22).

Source: NCFRP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

The socioeconomic background

2

of six (50%) of these 12 children was categorized as low,

while the economic background of the remaining six cases reviewed was unknown. The

evaluations of these fatalities brought aention to several risk factors, one of which was the

presence of notable Adverse Childhood Experiences (refer to the Shared Risk and Protective

Factors for Child Fatality in NM section, page 45).

2

According to the National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention, “Income level is an estimate

based on economic indicators such as caregiver education, social service enrollment, and health

insurance type; can assist in determining the child’s household income level. If no concrete evidence

exists regarding income, unknown is selected” (NCFRP, 2022).

Figure 22. Summary of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Child Fatalities Reviewed by NMCFR (CAN-H panel) in

New Mexico, 2022

38

Sudden Unexpected Infant Death (SUID)

Sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) is a term used to describe the sudden and

unexpected death of a baby less than one year old in which the cause was not obvious

before investigation. These deaths often occur during sleep or in the area where the infant

was placed to sleep.

Three commonly reported types of SUID include: sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS),

accidental suocation and strangulation in bed and unknown cause.

In 2022, 34 reviews of infant fatalities were conducted by the Sudden Unexpected Infant

Death (SUID) Panel. One case was reviewed twice by this panel. Three were ultimately

excluded from final analysis as the case characteristics did not meet inclusion criteria for the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s SUID Case Registry. The three excluded cases

are described further in the Exclusions subsection. More information about the SUID Case

Registry can be found at hps://www.cdc.gov/sids/case-registry.htm

Of the 30 unique cases which met inclusion criteria and were analyzed in this report, 16

(53.3%) were male and 14 (46.7%) were female, 14 (46.7%) were Hispanic or Latino, nine

(30%) were White, five (16.7%) were Native American, and two (6.7%) were Black or African

American. In terms of age, most were between 1-8 months of age. Three (10%) were less

than one month old, and one (3.3%) was more than nine months old. Table 6 displays counts

and percentages of cases by age.

Table 6. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR (SUID Panel) by Age Group in New Mexico, 2022

Age

Count

Percent

Sudden unexpected early neonatal deaths (SUEND), 0-6 days of life

0-6 days old

0

0%

Post-perinatal SUID, 7-364 days of life

< 1 month old

3

10%

1-4 months old

13

43.3%

5-8 months old

13

43.3%

9-12 months old

1

3.3%

Total

30

100%

Selected Risk Factors for SUID

Sleep and caregiver characteristics such as infant sleep position, surface and location which

increase the risk of SUID, as well as exposures and other risk factors, are described in the

2022 AAP Technical Report on SUID

(Moon, et al. 2023).

39

Of note, while surface sharing (adult or other person sleeping on the same surface, such as

adult bed, couch, recliner or futon) alone poses an increased risk of SUID, some additional

characteristics significantly increase the risk of accidental strangulation or suocation in

bed and wedging or entrapment. Bed sharing with someone who is impaired in their alertness

or ability to arouse because of fatigue or use of sedating medications (e.g., certain

antidepressants, pain medications) or substances (e.g., alcohol, illicit drugs), bed sharing

with a current smoker (even if the smoker does not smoke in bed) or smoking during

pregnancy can increase the risk of SUID by more than 10 times the baseline risk of parent-

infant bed sharing.

The following sections describe characteristics of NM SUID cases reviewed by NM-CFR in

2022:

Sleeping environment and place

In 20 cases (67%), the death was identified as related to an unsafe sleep environment. In

three cases, the infant was placed to sleep in a bassinet and in another two cases, the infant

was placed to sleep in a crib (Figure 23). Although cribs and bassinets meet

safe sleep

recommendations, the presence of other items are not recommended. Items such as soft

objects, like pillows, pillow-like toys, quilts, comforters, maress toppers, fur-like materials,

and loose bedding (blankets and nonfied sheets) increase the risk of suocation,

entrapment/wedging, and strangulation.

In fifteen (50%) cases, the infant was placed to sleep on an adult bed. In 17 cases (57%), the

infant was placed to sleep sharing a sleep surface with another person or animal. Of the 17

cases related to surface sharing, eight (27%) were noted to have no infant crib or safe sleep

space in the home. In one case (3%), the family was noted to be experiencing housing

insecurity and/or homelessness.

Source: N CF R P, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

2

3

15

1

3

1

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Crib Bassinet Adult bed Couch Other Futon

# SUID cases

Sleeping place

Figure 23. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR (SUID Panel), by Sleeping Place in New Mexico, 2022

40

Caregiver Impairment

Caregiver impairment is defined broadly by the NCFRP and includes being distracted or

absent, impaired by illness or disability, and impaired by substances such as medications,

alcohol or other substances.

An analysis of adult caregivers who were intoxicated by alcohol, medication or other

substances (prescribed or illicit) at the time of the incident was conducted. Of the 30 unique

SUID cases reviewed in 2022, six cases (20%) in which the adult caregiver was impaired were

identified, which may be an underrepresentation of the actual proportion. There were five

cases (17%) identified in which the adult caregiver was intoxicated by alcohol, and one (3%)

in which the adult caregiver was impaired by other substances.

SUID Categorization

Cases were categorized using the CDC SUID Registry Case Categorization Algorithm. Of the

30 unique cases reviewed in 2022, 13 (43%) were categorized as explained and determined

to be due to suocation with unsafe sleep factors; 11 (37%) were categorized as unexplained

with unsafe sleep factors present; two cases (7%) were categorized as unexplained,

possible suocation with unsafe sleep factors present and one case (3%) was categorized

as unexplained due to incomplete case information available.

Primary Mechanism of Injury

The primary mechanism of injury in eight cases (27%) was identified as soft bedding. In six

cases (20%), the primary mechanism of injury was overlay, and in one case (3%), it was

wedging.

Exclusions

Out of the 34 cases reviewed by the SUID panel, three cases were ultimately excluded

because they did not meet the criteria for SUID as described by the CDC, as their cause of

death was determined to be natural. Two (66.6%) of these cases were female and one

(33.3%) was male. All three were Hispanic or Latino. Among them, two cases fall into the one

to four months age category, while one case falls into the five to eight months age category.

41

Unintentional Injury

Unintentional injuries can be caused by poisoning, inhalation or ingestion, motor vehicle

crashes, falls, drowning, and structural fire or thermal injuries, firearms, or other

mechanisms. In 2022, 24 unique child fatalities were reviewed by the Unintentional Injury

Panel. Twelve (50%) of the cases reviewed were of children 15-17 years old (Figure 24).

Twenty-three cases (96%) were identified as preventable; only one (4%) case was identified

not to be preventable. Fifteen (62%) cases were males, and nine (37.5%) cases were female.

Twelve (50%) of the 24 children were Hispanic or Latino, five (20.8%) of which identified as

White, and six (25%) were Native American. The leading causes were asphyxiation (n=11,

46%), motor vehicle crashes (n=6, 25%), poisoning (n=3, 13%), falls (n=1, 4%), drowning

(n=1, 4%), bodily force or weapon (n=1, 4%), and other incidents (n=1, 4%).

Source: N CF R P, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

1

5

4

2

12

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

less than 1 1 to 4 5 to 9 10 to 14 15 to 17

# Unintentional Injury

Age Group

Figure 24. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR (Unintentional Injury Panel), by Age Group in New Mexico, 2022

42

Youth Suicide

Of the 16 unique cases of child suicide included in this report, fifteen (93.8%) were males and

one (6.3%) was female. Nine (60%) were white, four (26.7%) were Hispanic or Latino. Of the

reviewed cases, nine (56%) were in the 15 to 17 age group and seven (44%) were in the 10 to

14 age group (Figure 25).

Fifteen (93.8%) of the cases were identified as preventable by the NM-CFR; the team could

not determine preventability for one (6.3%) case.

10 to 14

15 to 17

Source: N CF RP, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

Mental Health Status and Suicide Ideation

Of the youth suicide cases reviewed in 2022, fourteen (88%) were identified as having

experienced a sense of isolation. Eleven (69%) had experienced a major life stressor or crisis

within the 30 days before their death. Prior to their death, seven (44%) children had

communicated thoughts or intention of suicide to someone else, and 69% had a history of

self- harm. Four (25%) experienced a change in behavior prior to their death. Three (19%)

were diagnosed with depression; two (13%) were diagnosed with anxiety. Two cases (13%)

had previously aempted suicide, yet none of the records reviewed indicated that a safety

plan was in place at the time of their death.

Figure 25. Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR (Suicide Panel), by Age in New Mexico, 2022

44

56

43

Half of the children (n=8, 50%) that died by suicide had received prior mental health

services. Six (37.5%) were actively receiving mental health services around the time of

death. Two (12.5%) children had been seen in the emergency department for a mental health

emergency within the last 12 months; however, no information was found about follow-up

appointments within 30 days.

Social Characteristics

Of the youth suicide cases reviewed in 2022, half (n=8, 50%) had parents who were divorced

or separated. Before their death, six (38%) had recently argued with their parents,

experienced a life stressor in terms of failure in school, or had been raised in a home with

domestic violence. Four (25%) had experienced housing insecurity; four (25%) had been the

victim of bullying. Two (13%) had experienced the death of a loved one, and two (13%) had

recently gone through a breakup with a significant other.

Figure 26. Summary of Suicide Ideation, Behavioral and Mental Health Status of Child Fatalities Reviewed by

NM-CFR (Suicide Panel), in New Mexico, 2022

44

Source: N CF R P, Last accessed: October 3, 2023

Figure 27. Summary of Stressful Events related to Child Fatalities Reviewed by NM-CFR (Suicide Panel), in New

Mexico, 2022

45

Shared Risk and Protective Factors for Child Fatality in NM

In this analysis, some themes about risk and protective factors emerged across the review

panels:

Life Stressors & Mental Health as a Risk Factor for Child Fatality

Through the cases reviewed in 2022, some shared risk factors were identified: life stressors

such as failure in school, death of a loved one, argument with parents, bullying, parents

divorced/separated, recent breakups, and mental health challenges (thoughts or intentions

of suicide, depression or anxiety, self-harm, prior suicide aempt).

Lack of Mental Health Services as Risk Factors

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), New Mexicans are 1.5 times more

likely to be forced out-of-network for mental health care than for primary health care. More

than 59% of New Mexicans aged 12–17 who have depression did not receive any care in the

last year.

In the analysis of youth suicide cases reviewed, four (25%) of 16 cases were identified as

having several issues leading to non-utilization or underutilization of mental health services.

These issues included: lack of providers in rural areas, refusal of parents or child to

participate or utilize referrals, stigmas around mental health or about receiving mental health

supportive services, and travel distance to services.

Access to Lethal Means as a Risk Factor for Child Fatality

Access to lethal means such as firearms, medication and other instruments or objects which

may result in intentional injury increases the risk of death by homicide and suicide, as well as

other unintentional injuries such as accidental gun deaths and accidental overdose.

Eighteen percent (n=15, 17.8%) of all 84 cases reviewed in 2022 were due to firearm injury.

Nine (56%) suicide deaths were due to firearm injury. Five (41.7%) of the 12 cases reviewed by

the CAN-H panel were due to firearm injury. One unintentional injury death reviewed in 2022

was by firearm. Four (16.7%) cases reviewed by the Unintentional Injury panel were due to

accidental overdose.

A 2023 report by the NMDOH

, Comprehensive Report on Gunshot Victims Presenting at

Hospitals in New Mexico, identified lack of safe storage as risk factor for firearm injury and

death. Reducing access to lethal means through safe storage of firearms and medication

could save lives in the future.

46

Lack of Supervision as a Risk Factor for Child Fatality

According to the NCFRP, lack of supervision is defined as a child who did not have supervision

but needed it, with children less than age six requiring constant supervision most of the

time. In addition, if the supervisor of a child younger than age six could not see or hear the

child at the time of need, this would be considered lack of supervision.

For the 84 children included in this report, at the time of the incident which led to the child’s

death, less than half of children (n=38, 45.2%) were supervised at the time of death and 17

children (20.2%) did not have supervision and needed it. In 15 (17.9%) cases, the child who

died was of suicient developmental age and circumstances to supervise themselves. In one

case, the NM-CFR was not able to determine the child’s supervisory need. Thirteen (15%)

cases did not have any response entered in the database.

Regardless of supervision status at time of incident leading to death, 38 of the 84 (45%)

cases analyzed contained information about the last time a primary person responsible for

supervision at time of incident saw the child: in 26 (30.5%) of those cases, the deaths

occurred when the child was in sight of the supervising individual; two deaths (2.3%)

occurred when the child was out of sight of the supervising individual for less than an hour;

nine deaths (10.7%) occurred when the child was out of sight of the supervising individual for

more than an hour.

A range of risk factors were identified from the available records of 55 children who were

noted as needing supervision or who were under parents/caregiver(s) supervision at the

time of their death. In 21 (38.1%) cases, the individual responsible for supervising the child

was asleep at the time of the child’s death. Seventeen children (30.9%) were supervised by

an individual who had a known history of child maltreatment. Thirteen children (23.6%) were

supervised by an individual with a known history of substance use disorder. Ten children

(18.2%) were supervised by an individual who was convicted of a crime. Nine children (16.3%)

were supervised by an individual who had a history of intimate partner violence victimization.

Six (10.9%) child deaths occurred in situations where the supervising adult was impaired

(defined by the NCFRP as being “distracted or absent, drug or alcohol impaired, and/or

impaired by disease or disability”). Five (9%) child deaths occurred in situations where the

supervising individual had a disability or chronic illness.

Adverse Childhood Experiences as a Risk Factor for Child Fatality

NM Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System data indicate that an estimated 68% of

adults residing in NM experienced at least one ACE, and nearly one in four (23.8%)

experienced four or more ACEs (Whiteside, 2021). As a person’s number of ACEs increases,

so does the risk for negative health and life outcomes.

Among the 84 cases reviewed in 2022, 30 children (35.7%) had a history of maltreatment

with a perpetrator parent. Eighteen children (21.4%) had lived with at least one parent who

47

was convicted of a crime. A history of referral to child welfare services was found in 10 cases

(12.4%). Thirteen children (15.5%) experienced multiple challenges in school such as

academics, truancy, suspension, or behavioral issues. Eighteen (21.4%) had history of

intimate partner violence, and 19 (22.6%) had history of substance misuse.

Child Maltreatment & Child Health as Risk Factors for Child Fatality

A history of child maltreatment has been identified as a risk factor for preventable child

fatality (Jonson-Reed, et al., 2022). Twenty-seven (32.1%) of the 84 cases reviewed by NM-

CFR in 2022 had a history of child maltreatment, and four (4.7%) had open investigations at

the time of their death. Eight children (9.5%) had a history of being placed into foster care at

any time prior to their death.

Child health status can also be a stressor for families that increases the risk of child fatality.

Twenty-one (25%) children had a known prior disability or chronic illness. Nine children

(10.7%) were receiving mental health services prior to their death and another 15 children

(17.9%) had received mental health services in the past. Nineteen children (22.6%) had a

history of substance use prior to their death.

Socioeconomic Status (SES) as a Risk Factor for Child Fatality

Social determinants of health, the conditions in which people live, work and play, have a

significant eect on health and well-being. Socioeconomic status (SES) is a notable finding

in this analysis. Two children (2.4%) were classified as having high household income, 11

children (13.1%) were classified as having medium household income, 30 cases (35.7%) were

classified as having low household income, and 29 (34.5%) cases were unknown or unable to

classify.

Health insurance information gives further insight into the SES of these children. A

2021

factsheet by NAMI indicated that 9.8% of people in NM are uninsured. In the analysis of

insurance status for the 84 unique child fatalities reviewed by NM-CFR in 2022, 48 cases

(57.1%) had Medicaid as their insurance coverage, 30 cases (35.1%) had private insurance

coverage, and one child (1.2 %) had no medical coverage. Twenty-two (26.2%) case records

indicate that their mothers received prenatal care, a known preventive factor of child fatality.

In the cases reviewed and analyzed in this report, social determinants such as household

income, geographic location, or education level may have prevented these children or their

parents/caregivers from equitable access to and use of healthcare services.

48

Limitations

A limitation of this report is that data were missing for several variables. During the

comprehensive review of these cases, certain information was unavailable due to various

factors, such as records requests which were not received by the agency. In cases where

there were diiculties in accessing data, it was necessary to classify certain values as

'unknown'. This lack of comprehensive data may contribute to underrepresentation of some

variables in this report.

Conclusions

Child deaths due to injury and violence are predictable and preventable. Of the unique 84

child fatalities reviewed in 2022 and described in this report, NM-CFR determined that 67

(79.76%) deaths could have been prevented. In most cases, there was suicient data for the

NM-CFR to determine preventability, however, in five (5.6%) cases, the information provided

was insuicient to determine whether the child’s death was preventable. Based on child

fatality data from reviews conducted during calendar year 2022 and analyzed in this report,

the leading causes of death were: asphyxiation (30%), bodily force or weapon (27%),

unknown (20%), and motor vehicle crashes (11%), followed by poisoning (5%), drowning

(3%), and other incidents (3%). The most common circumstances surrounding child deaths

in NM included risk factors and a lack of protective factors in areas of access to lethal means,

behavioral and mental health care, supervision, income level in family, maltreatment, and

violence.

A broad evidence base demonstrates that social determinants of health, such as educational

aainment, economic stability, social and community dynamics, neighborhood

characteristics, and access to quality healthcare, as well as discriminatory policies, systemic

violence and historical trauma contribute to the manifestation of complex and

interconnected risk factors for children and families. Enacting preventative measures can

reduce risk factors such as adverse childhood experiences, mitigating trauma and creating a

protective environment to reduce the occurrence of child fatalities.

Recommendations to prevent adverse childhood experiences and promote positive

childhood experiences to increase protective factors include strengthening economic

supports for families; promoting social norms that protect against violence and adversity;

ensuring a strong start for children; teaching skills; connecting youth to caring adults and

activities; and intervening to lessen immediate and long-term harms.

The next section describes key prevention recommendations made by NM-CFR.

49

NM-CFR Recommendations

Previous Recommendations

Although some recommendations from previous years have not yet been implemented, and

may not be included in this report, the NM-CFR recognizes the continued need for adoption.

Exclusion from this report should not be interpreted as a discontinued need. The key

recommendations were selected and included in this report based on current public health

and social conditions, as well as alignment with departmental priorities.

Some recommendations that were made by NM-CFR panelists in 2022 have since been

implemented, and thus excluded from the Key Recommendations. The following actions have

been taken based on previous recommendations of the NM-CFR:

A long-standing infant injury prevention recommendation of the NM-CFR included shaken

baby syndrome (SBS) prevention. In 2017, the Shaken Baby Syndrome Educational Materials

Act was enacted in NM, which requires hospitals and freestanding birth centers to provide

training and education to prevent SBS to every parent of every newborn before discharge.

One recommendation made in 2022 was for the NM-CFR to develop a panel to address

violence aecting youth, oftentimes, but not limited to causes by firearm injury. In 2023, the

NM-CFR created a new panel to review cases related to community and/or peer violence.

Another recommendation which was made in previous years as well as in 2022 was for a

legislative mandate for the safe storage of firearms in homes with children. In 2023,

House

Bill 9, the Bennie Hargrove Gun Safety Act was enacted, which prevents gun violence by

requiring gun owners to keep firearms safely stored.