Quality Jobs for Quality Care

The Path to a Living Wage for Nursing Home Workers

November 2015

Page 1

About Massachusetts Senior Care Association

The Massachusetts Senior Care Association represents a diverse set of organizations that deliver a broad

spectrum of services to meet the needs of older adults and people with disabilities. Our members

include more than 500 nursing and rehabilitation facilities, assisted living residences, residential care

facilities and continuing care retirement communities.

Forming a crucial link in the continuum of care, Mass Senior Care facilities provide housing, health care

and support services to 150,000 people a year; employ more than 77,000 staff members; and contribute

more than $4 billion annually to the Massachusetts economy.

Since its founding in 1949, Mass Senior Care's mission has been to improve the quality and delivery of

long term care services in Massachusetts through research, education and advocacy.

Acknowledgments

A team of Massachusetts Senior Care Association staff contributed to this report, including Director of

Labor and Workforce Development Kelly Aiken, Director of Reimbursement Gary Abrahams, Director

of Public Affairs Jennifer Chen and Senior Vice President Tara Gregorio. Mass Senior Care would like to

acknowledge the following Board members for their contributions, insights and critical feedback on this

report: William Bogdanovich, Chairman, Massachusetts Senior Care Association, President and CEO,

Broad Reach Rehabilitation and Skilled Care Center at Liberty Commons; Marva Serotkin, President,

Massachusetts Senior Care Foundation, CEO, The Boston Home; Matthew Salmon, CEO, SALMON

Health and Retirement and Richard Bane, President, BaneCare Management. Special thanks to external

reviewers Steven L. Dawson, Strategic Advisor, PHI on behalf of the National Fund for Workforce

Solutions and Christine Bishop, Atran Professor of Labor Economics, The Heller School for Social Policy

and Management, Brandeis University.

Page 2

Quality Jobs for Quality Care:

A Path to a Living Wage for Nursing Home Workers

Executive Summary

The commitment and dedication of the state’s long term care workforce has propelled Massachusetts into

a position of national leadership in providing quality long term care services to frail elders and people with

disabilities who can no longer live safely in the community. Seventy-seven thousand nursing home staff

work tirelessly in the Commonwealth’s more than 400 long term and post-acute care facilities to ensure

residents and their families receive the quality care and support they need and deserve. Their ability to

deliver quality care is dependent on the quality of their jobs.

While nursing home consumer satisfaction remains high and hospital readmissions have declined, over half

of nursing home staff do not have access to the most essential element of a quality job – a living wage.

Most often this impacts immigrants and single mothers who view their job in a nursing home as a starting

point on a career pathway to making a family-sustaining wage.

Seventy-ve percent of a nursing home’s budget is used to fund employee wages and benets. With

MassHealth funding the care of over two-thirds of nursing home residents, wage increases for nursing home

staff are predominantly dependent upon adequate MassHealth payment by the Commonwealth. Since

2008 there has been little state investment in nursing home care for MassHealth residents. Consequently,

certied nurse aides (CNAs) have seen a mere 4% cumulative increase in actual wages over the last seven

years and a 6% decline in real wages for this 2008-2015 period. CNAs working in other settings such as

hospitals can now earn as much as 20% more, leaving nursing homes at a competitive disadvantage. In

addition, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker has committed to a goal of providing a $15 per hour

starting wage for the state’s Personal Care Attendants (PCAs) in 2018.

Ensuring staff stability and job satisfaction is critical to providing quality care in nursing homes. Recruiting

and retaining qualied staff passionate about working with frail elders and people with disabilities is an

ongoing priority for Massachusetts nursing home providers. However, that has become increasingly

challenging. CNA vacancy rates have doubled over the last ve years leaving one in ten positions unlled.

As the economy improves, there is increased recruitment competition among nursing facilities, hospitals,

assisted living residences and home care agencies for CNA staff, which is further exacerbated by a decrease

in the supply of newly trained CNAs. Projected declines in the caretaking workforce, women age 25 to 44,

will only make matters worse over the next 10 years.

Wages play a critical role in dening quality jobs, but other elements such as benets, job security, fair work

schedule, career advancement and a supportive work environment are also crucial. While skilled nursing

facilities offer many of the elements of a quality job, there is opportunity for improvement. A combination

of strategies is needed to create quality jobs that provide higher wages and an improved working

environment to increase retention of existing staff and recruitment of new staff.

Page 3

Recommendations for Investment

The Massachusetts Legislature funded the Nursing Home Quality Initiative beginning in 2000. This multi-

pronged initiative, which became a national model, demonstrated that increased state investment in nursing

homes improved job quality, while enhancing resident care. A similar investment in quality nursing home

care is needed to fund the following recommendations:

• Create a Pathway to a Living Wage – Develop a multi-year funding strategy that includes

both an immediate and annual wage pass-through for the lowest wage workers including CNAs,

dietary, laundry and housekeeping staff, tying the wage increase to the Consumer Price Index.

• Support a Culture of Retention – Fund the rollout and implementation of comprehensive

evidence-based supervisory training for the express purpose of retaining staff and reducing turnover.

• Establish a CNA Scholarship Program – Support more adults in their quest for post-

secondary credentials by providing scholarships for integrated training that includes both

Adult Basic Education/English as a Second Language and CNA training.

By investing directly in nursing home staff, Massachusetts will remain a leader in providing quality care for

residents and their families and improve the lives of thousands of workers across the Commonwealth.

Page 4

Introduction

Seventy-seven thousand dedicated nursing home staff deliver high quality care to frail elders and people

with disabilities every day in the Commonwealth’s 400 long term and post-acute care facilities. As a result

of the tireless commitment and dedication of its workforce, Massachusetts is a national leader in providing

quality long term care services to individuals who can no longer live safely in the community. Massachusetts

facilities have among the highest percentage of Department of Public Health “deciency free” nursing

facilities compared to the national average. Consumer satisfaction remains high and hospital readmissions

have steadily declined. As the population ages and demand for long term care services continues to rise,

these quality accomplishments can only be maintained and improved upon when nursing home staff are

recognized and supported for their commitment to providing excellent care.

Quality care in all facilities is dependent on quality jobs and staff stability. Hiring and retaining qualied

staff passionate about working with frail elders and people with disabilities remains an ongoing priority

for Massachusetts nursing home providers. However, state underfunding for nursing home services has

resulted in non-competitive wages and high staff vacancy rates. Seventy-ve percent of a nursing home’s

budget is used to fund employee wages and benets. And, with MassHealth funding the care of over two-

thirds of nursing home residents, a nursing home’s ability to invest in staff is largely dependent upon state

funding. As a result, many nursing home workers, particularly certied nurse aides (CNAs) and dietary,

housekeeping and laundry aides, cannot afford to do the work they love because of persistent low wages.

This often forces staff to seek employment elsewhere and leads to disruptions in resident care. It is

critically important to ensure that staff instability does not negatively impact quality of care for residents

and their families.

Forty thousand full-time and part-time entry level positions in nursing homes offer a critical employment

gateway for immigrants, women previously out of the labor market, young adults and others seeking a

healthcare career. The majority of entry level staff work as CNAs, providing direct care and companionship

to residents while assisting with activities of daily living such as eating, walking and bathing. Equally

important to the lives of residents is ancillary staff indirectly associated with patient care such as dietary,

housekeeping and laundry aides.

The entry level nursing home workforce is predominantly women between the ages of 18-44 and highly

diverse with 48% of CNAs self-identifying as Latino or nonwhite (American Community Survey, 2010).

Many are single parents with young children. Frequently a rst job in a nursing home is a career starting

point and can provide a pathway to advanced education and a family sustaining wage.

Yet, in today’s environment these entry level nursing home workers do not have a clear pathway to a living

wage - the most essential element of a quality job. Skilled nursing facilities do offer many other elements

of a quality job, including benets, job security, fair work scheduling and career advancement. However, a

sustained approach to high quality jobs for high quality care requires investing in wages, workers and the

work environment.

Page 5

Current Entry Level Staff Wages

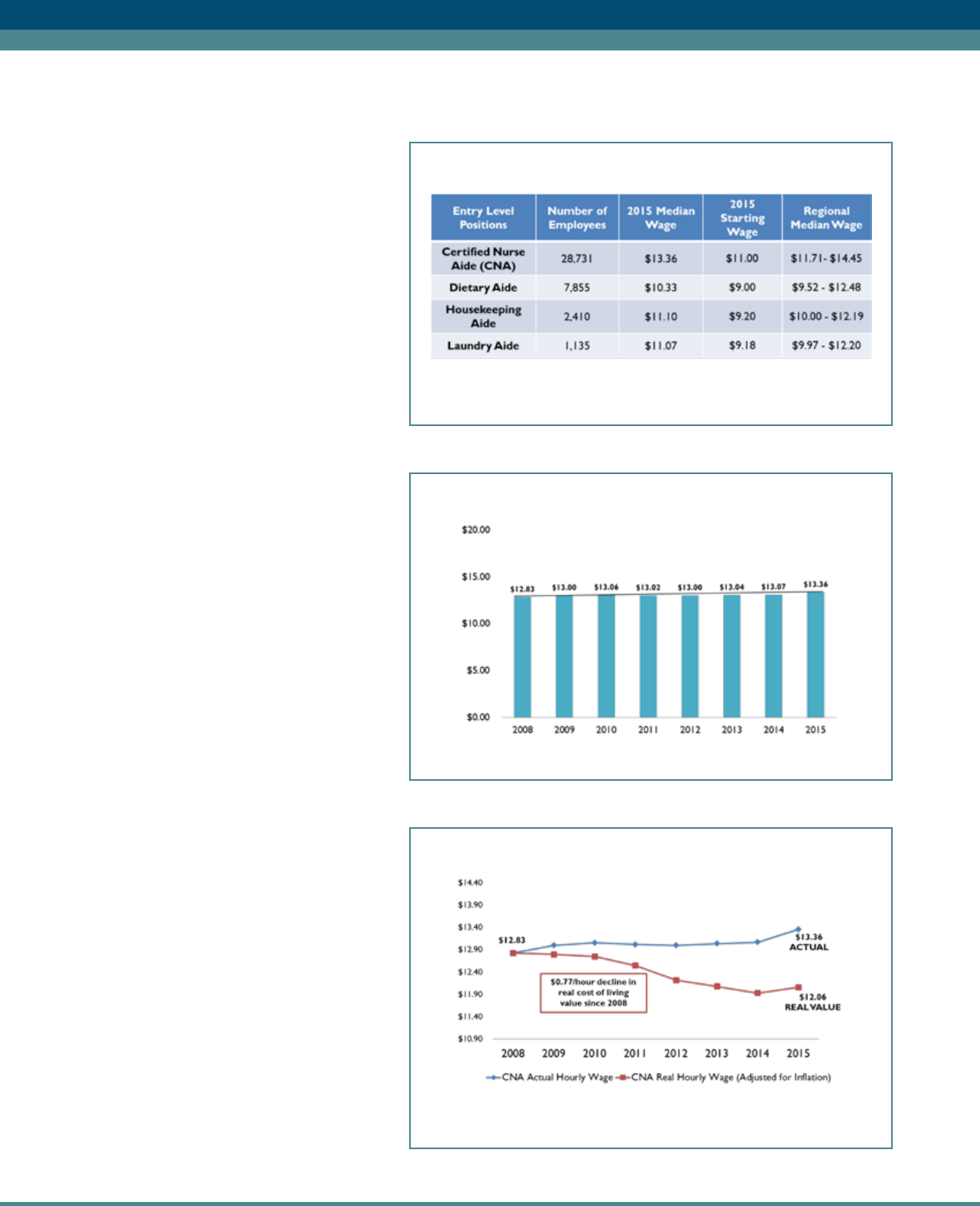

Although their services are vital to

maintaining the health, dignity and quality

of life for nursing home residents, the

2015 statewide median CNA wage is

only $13.36 per hour or $2,316 per

month if working full-time. Median

ancillary staff wages are even lower

ranging from $10.33 to $11.10 per

hour. Across the state, regional wage

variation exists as well (See Appendix

for a breakdown of wages by county).

These low wages dramatically impact the

quality of jobs and the lives of nursing

home workers and their families.

CNA wages have remained stagnant,

growing only 4% cumulatively from

2008-2015 (Chart 1). If adjusted for

ination, CNA real wages have actually

fallen by 6% through 2015. As seen in

Chart 2, this represents a $.77/hour

decline in real cost of living value over

this seven year period. By contrast, the

cost of living in the Metro Boston Area

increased by 11% for this period. And,

with the fair market rent of a two-

bedroom apartment totaling $1,494

per month in Metro Boston, a CNA

would have to spend about 60% of her

annual wages on housing (National Low

Income Housing Report, 2013). Across

the state, the cost of living for CNAs

has signicantly outpaced wage increases

(MSCA, 2015).

Sources: Mass Senior Care Association Annual Employment Survey,

2015 and CHIA Nursing Home Annual Cost Report

Table 1: 2015 Entry Level Staff Wages

Chart 1: Median CNA Hourly Wage (2008-2015)

Source: Mass Senior Care Association Annual Employment Surveys

Chart 2: Real vs Actual CNA Wages (2008-2015)

Sources: Massachusetts Senior Care Annual Employment Surveys

and CPI – Bureau of Labor Statistics

Page 6

What is a Living Wage?

A living wage provides a wage and benets package that takes into account the area-specic cost of living,

as well as the basic expenses involved in supporting a family. By working a single full-time job, an individual

should be able to rent an apartment and pay for other monthly expenses like food and transportation. In

the calculation of a living wage, the Crittenton Women’s Union Economic Independence Calculator takes

into consideration monthly expenses, cost of child care and health care, regional cost of living and taxes.

Using their calculator, a nursing home CNA making the state’s 2015 median base hourly wage will not meet

the living wage requirements for a single parent with one child living in Massachusetts. For example, in 2013

the living wage in Waltham exceeds $24 per hour for one adult with a school aged child. For one adult

living in Waltham, the living wage was $15.05/hour.

Across the state, the CNA base hourly wage meets less than 70% of the standard living wage for a family of

one adult and one child. This is particularly alarming because many low wage workers are single parents and

Massachusetts ranks among the least affordable states for center-based preschool care (Child Care Aware,

2014).

To make ends meet, many CNAs and ancillary staff hold more than one job and rely on public benets.

Anecdotal evidence and CNA interviews suggest the majority of low wage staff juggle multiple jobs and

sometimes work 75-80 hours per week. The Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute (PHI) reports that over

54% of CNAs and home health aides in Massachusetts receive some form of public assistance such as

MassHealth or Food and Nutrition and 42% live in households earning incomes below 200% of the federal

poverty level (PHI, 2012 and 2015).

Why Nursing Homes Cannot Pay Their Employees A Living Wage

Nursing homes are a major economic contributor both statewide and in local communities across the

Commonwealth. In many rural communities, nursing homes are the largest healthcare employer in the

region. Every year the sector generates $4.3 billion in economic activity with $3 billion in labor spending.

As seen in Chart 3, $.75 of every nursing facility “dollar” funds employee wages and benets which means a

nursing home’s ability to invest in staff is dependent upon state funding.

Table 2: “Living Wage” vs. Actual CNA Wage in Waltham

Source: Economic Independence Calculator, Crittenton Women’s Union, 2013;

Mass Senior Care Association Annual Employment Survey (Actual CNA Wage, 2015)

Page 7

In comparison to other healthcare employers such as hospitals and home health agencies, state funding is a

much more critical determinant of nursing home wages. With the care of over two-thirds of nursing home

residents paid for by MassHealth, Massachusetts nursing facilities are uniquely dependent upon state funding

to ensure quality resident care and quality jobs. Years of MassHealth underfunding for nursing home care

has caused a $37 per day gap between the cost of providing resident care and MassHealth payment. This

funding crisis has made it virtually impossible for

nursing home providers to ll staff vacancies and

make meaningful investments in their workforce.

It is important to highlight this direct relationship

between adequate Medicaid funding for nursing

home care and increases in wages for nursing

home employees. From 1999-2008, MassHealth

made signicant investments in nursing home care

and nursing homes passed along these Medicaid

rate increases to their staff through annual wage

hikes. Since the start of the “Great Recession” in

2008, there has been little growth in MassHealth

funding for nursing home care (See Chart 4). As a

result, CNA wages stagnated for the period 2008-

2015, growing only 4% over the entire seven year

period from $12.83 per hour to $13.36 per hour (see Chart 1). The inability of nursing homes to provide

wage increases has understandably resulted in valuable staff leaving for higher paying jobs in other parts of

the healthcare system including hospitals, where CNAs can earn over 20% more (See Chart 5).

Chart 3: Breakdown of Nursing Home Spending

Source: DHCFP/CHIA Nursing Home Cost Reports

Chart 4: Direct Link Between Annual

Medicaid Rate Changes and Nursing Home

Wage Increases (1999-2013)

Source: DHCFP/CHIA Nursing Facility Cost Reports,

Prepared by Mass Senior Care Association

Chart 5: Health Care Aide Wage and Medicaid

Dependency by Provider Type (2014)

Sources: Mass Senior Care Association Annual Employment Survey,

2014 (NF); Home Care Alliance of Massachusetts 2014 Employment

Survey (Home Health Agency); and Bureau of Labor Statistics

Occupational Employment Statistics (Hospital)

Page 8

Critical Demand for Services

Even as consumers receive more care and services in their homes, the demand for long term care services

over the next 15 years is expected to rise dramatically to keep pace with the growth of the over 65

population. From 2015 through 2030, the 75-84 age cohort will increase by close to 70%. “Younger”

seniors age 65-74 will grow by over 40%. Both cohorts will increase demand for short stay post-acute and

rehabilitative care in skilled nursing facilities. The 85+ age cohort, the group most likely to need long term

care services, will grow substantially (over 21%) but at a slower pace than the 65 through 84 population

over the next 15 years (UMass Donahue Institute 2015 Population Projections, March 2015). While many

older adults will seek to engage services enabling them to age at home or in their communities, nursing

home care will be critical for those who can no longer safely age in place or need assistance during short

term recovery.

With the state’s successful “Community First” policy and increased investments in community-based

services, many individuals who need residential long term care services are accessing nursing home care

later in their illness. Their acuity level increases the demands on frontline staff, requiring additional training

to keep pace with delivering quality care in a more complex environment. All of these factors reinforce the

critical importance of stabilizing the nursing home workforce now and ensuring access to quality jobs.

Staff Vacancies Expected to Increase

The nursing home provider community has a history of workforce shortages that ebb and ow with the

economy. In September 2015, Massachusetts posted a 4.5% unemployment rate compared to 5.1% at the

national level. As the state moves to a full employment economy, competition for low wage workers is

expected to increase across all industries. In previous periods of full employment, PHI notes that “prevailing

wage rates have made it difcult for many long term care providers to compete for workers with employers

offering less physically and emotionally demanding low wage jobs” (PHI, 2003).

In ve years, the CNA vacancy rate has nearly doubled to 10.6%. As illustrated in Chart 6, one in ten

unlled CNA positions across the state equates to approximately 2,270 open and unlled positions (MSCA,

2015). Vacancy rates and the number of open positions vary across the state, with Middlesex, Worcester

and three Western Massachusetts counties (Franklin, Hampshire and Hampden) accounting for almost half

of all vacant CNA positions. These counties have the highest concentration of nursing homes in the state.

Chart 6: CNA Vacancy Rates and Estimated Unlled Positions (2015)

*Western Mass = Franklin, Hampshire and Hampden Counties

Source: Mass Senior Care Association Annual Employment Survey, 2015

Page 9

As vacancy rates increase so does job stress for incumbent CNAs who often are left to work short staffed

and additional hours. In 2015, an estimated $40 million was paid to nursing facility staff for overtime as well

as additional expenditures for contracting with temporary nursing agencies.

Despite the high number of nurse aide training programs, competition for qualied CNA staff is increasing.

Originally only employed by nursing homes, CNAs now nd work in hospitals, assisted living, residential

mental health facilities, and home care agencies. In fact, the nurse aide has become the “universal worker”

for employers in many care settings. Employers value the basic skills development provided by the training,

as well as the competency assessment required by the state certication process and the certied nurse

aide registry maintained by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH). Competition is

exacerbated by a 5% drop in the number of new nurse aides added to the nursing aide registry from state

scal year 2014 to state scal year 2015 (Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2015).

Current demographic projections suggest that the primary labor force, comprised of women age 25 to 54,

is expected to shrink over the next 10 years. This will likely further decrease the number of caregivers

available for the growing number of people who will require long term care services.

Staff Stability Impacts Quality of Care

Skilled nursing facilities in Massachusetts boast a higher than average staff retention rate when compared to

national statistics. The 2015 Massachusetts Senior Care Association wage and salary survey data indicates

that 70% of CNAs have worked in the same facility for one year or more. Many facilities have a strong core

of long term, dedicated employees. However, a smaller percentage of employees turn over more frequently.

This staff turnover impacts the continuity of resident care and costs the provider community an estimated

$35 million every year (MSCA, 2015).

In addition to disrupting continuity of care, high turnover rates and job dissatisfaction result in deteriorating

performance on quality indicators such as use of physical restraints, catheter use and pressure ulcers.

Conversely, when staff satisfaction is high nursing homes report fewer resident falls, fewer pressure ulcers,

and decreased use of catheters. Improved staff satisfaction also translates into reduced staff turnover and

absenteeism (Castle, 2007).

Studies have identied a number of factors that are associated with CNA job satisfaction, including higher

pay, assistance in alleviating job stress, and supervisors who show care and concern for their well-being.

The Institute of Medicine found that positive supervision can greatly increase direct care workers’ sense of

value, job satisfaction and intent to stay (Institute of Medicine, 2008). Supervisors and managers who are

trained to support staff and engage them in decision making demonstrate a higher level of care and concern

resulting in higher retention rates (Commonwealth Corporation, 2007).

Registered nurses and licensed practical nurses manage and supervise CNAs, yet few nurses have been

afforded adequate management skills training in their nursing education or have any experience supervising

staff before taking on the responsibility in a nursing home. Training for supervisors supports the pivotal role

that managers play in creating a culture of retention.

Page 10

Dening Job Quality Beyond Wages

While wages play an important role in dening quality jobs, other indicators contribute to the denition

as well, including: benets such as paid time off, health insurance, job security, fair work schedule, and a

supportive work environment. PHI maintains that the essential elements of a high quality job are fair

compensation, opportunities for professional growth and adequate support. Using these standards,

Massachusetts nursing homes offer higher quality entry level positions than many other industries. Some

examples include the following:

Benets: All nursing home staff have access to paid time off with an average of 27 days including vacation

and sick leave. A majority of facilities offer short and long term disability to full-time staff. While retirement

benets and health and dental insurance are also available, entry level staff are often unable to afford

participation in these programs. Many low wage staff rely on MassHealth for individual and family health

insurance.

Work Schedule and Job Security: Nursing homes offer year round stable jobs with consistent hours.

A variety of 24/7 work options are available to workers including full-time, part-time and per diem shifts.

There is no mandated overtime. Advance scheduling is the norm offering staff one or two week notice of

the upcoming schedule.

Career Advancement Opportunity: Nursing homes offer a career pathway for CNAs to become a

licensed practical nurse (LPN) or a registered nurse (RN), both positions that pay a family-sustaining wage.

In some facilities, interim pathway steps also include becoming a senior CNA. For those who need basic

skills development in order to advance, almost every community college across the state is working with

local nursing homes to provide easy access to college prep courses and adult basic education. Over 70%

of employers offer tuition assistance to employees to support additional education. There is also a 30 year

history within the provider community of supporting advancement opportunities by contributing to the

Massachusetts Senior Care Foundation Scholarship program which, over that time, has distributed some

$2.7 million in scholarships to 1,500 employees. However, the educational pathway to a family-sustaining

income for many is long and has opportunity costs, especially when juggling more than one job and a family.

Supportive Organizational Culture: Many Massachusetts nursing homes have created an organizational

culture modeled on principles of resident-centered care that promote choice, purpose and meaning in daily

life for frail elders and persons with disabilities. In a resident-centered care organization, staff form stronger

relationships with residents and their families because they consistently take care of the same individuals

enabling them to know a person’s preferences and better anticipate their needs. Staff is highly valued in

these types of organizations and it results in increased retention rates and improved quality outcomes.

Participating in Decision Making and Engaging in Continuous Quality Improvement: Enabling

CNAs and others to participate in decision making including care planning is an important aspect of

organizational culture and job satisfaction. Promoting continuous quality improvement in a manner that

integrates CNAs in the care planning process and provides specic tools for improving communications

and interactions with residents is equally important. Massachusetts nursing homes are leaders in

quality improvement initiatives, such as OASIS, a unique non-pharmacological approach to reducing

the use of antipsychotic medications in nursing home residents. Through a grant made possible by the

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Bureau of Health Care Quality and Safety, staff from nearly

75% of Massachusetts nursing homes have participated in OASIS training, gaining the knowledge and tools

Page 11

that enable them to provide more individualized care to a broad range of residents, including those with

dementia. The active participation, engagement and leadership of CNAs, built on the strong relationships

they have with their residents, have contributed to OASIS’ success in improving dementia care and a 29%

reduction in antipsychotic drug use for long-stay residents in Massachusetts nursing homes (CMS Quality

Measures, 2011-2015).

While skilled nursing facilities meet many of the quality jobs criteria, it is just a foundation and there is a

critical need for improvement. Multiple strategies are needed to create quality jobs that provide higher

wages and an improved working environment to increase retention of existing staff and create a welcoming

environment to new employees.

State Investment in Workers Pays Off

History of Investment in Quality Jobs

The late 1990s was a period of economic distress for the nursing home provider community, creating

instability that threatened quality and access to care, evidenced in high turnover and vacancies among direct

care workers. In response, the Massachusetts Legislature enacted and funded the Nursing Home Quality

Initiative rst in 2000. Additional signicant investments in the nursing home workforce were also made in

subsequent years. The initial $42 million initiative focused on increasing high quality nursing home care for

residents and families by providing good jobs and opportunities for frontline caregivers (Eaton, 2001). The

core components of the initiative included: 1) a wage pass-through for direct care workers; 2) an education

and training program for workers and supervisors entitled the Extended Care Career Ladder Initiative

(ECCLI); 3) a direct care worker scholarship program; and 4) a statewide nursing home resident family

consumer satisfaction survey.

Improving Job Quality by Increasing Wages and Training

The Nursing Home Quality Initiative had a dramatic impact on Massachusetts’ nursing homes and their

workers. The wage pass-through allocated funds provided through Medicaid reimbursement for the express

purpose of increasing compensation for direct care workers. This resulted in a 15% increase in CNAs

median hourly wage from $10.22 in 2000 to $11.73 in 2003.

ECCLI was a career pathway program for CNAs and home health aides with the primary goal of enhancing

the quality and outcomes of resident/client care while simultaneously addressing the dual problems of

recruiting and retaining a skilled direct care workforce. From 2000-2010, 9,000 frontline staff and managers

from over 175 facilities participated in ECCLI training activities. Evaluation of the program demonstrated

that opportunities for education and career advancement improved frontline workers’ sense of self-

condence and respect which led to improvements in the quality of resident/client care. For example,

results showed that the rate of worsening behavioral symptoms were signicantly reduced among resident

in nursing home that participated in ECCLI, compared to those that did not participate (Commonwealth

Corporation, 2007). Supervisory training fostered an environment of trust and respect which signicantly

impacted staff satisfaction. Providing English as a Second Language (ESL), adult basic education (ABE) and

career readiness courses enabled more staff to develop the needed basic skills to pursue post-secondary

education. In many cases, staff advanced from CNA to a LPN or RN thereby securing a family-sustaining

wage. Finally, offering career ladders and training opportunities made organizations more attractive to

potential new employees thereby improving staff recruitment efforts.

Page 12

Increasing Supply of CNAs

The Direct Care Scholarship Program was designed to increase the supply of direct care workers. From

2001-2008, the program provided free training and state certication to 3,800 people enabling them to

work as CNAs and home health aides in nursing homes and community settings across the state. Program

outreach and free training removed barriers for those who could not otherwise afford the cost of training.

It also provided people with the credentials needed to access a stable career with opportunities for

professional growth.

Increased Satisfaction with Nursing Homes

As part of the Legislature’s investment in the Nursing Home Quality Initiative, the Massachusetts Department

of Public Health measured consumer satisfaction of family members with relatives in the Commonwealth’s

nursing homes. In 2004, after four years of investment, the statewide survey found an exceptionally high

degree of satisfaction with the care their loved ones received. By 2007, nine out of ten surveyed said

they would recommend their loved one’s nursing home to a friend or family member (Massachusetts

Department of Public Health, 2007).

Ultimately, the Nursing Home Quality Initiative demonstrated that adequate and sustained state investment

in nursing homes and their staff resulted in higher quality nursing home care for residents and families as

well as higher quality jobs and increased opportunities for frontline caregivers. From 2000-2005, CNA

vacancy rates dropped 40% from 15% to 9% and the use of temporary agency staff dropped by 78%. At

the same time, CNA retention rates improved by 16% which resulted in 78% of full-time CNAs maintaining

employment at the same nursing home for 12 months or more (MSCA, 2000-2005). ECCLI has since

gone on to become a national model for workforce development, promoting public-private partnerships to

strengthen the long term care workforce and improve the quality of long term care services.

Recommendations

It is imperative that the state increase its investment in nursing homes across the Commonwealth. The

quality of resident care and the quality of jobs depends on it. Massachusetts Senior Care Association offers

the following recommendations.

Create a Pathway to a Living Wage

CNAs and ancillary staff earn some of the lowest wages in the state, and even with Massachusetts' universal

health care law, many struggle to afford adequate health coverage for themselves and their families.

Creating a pathway to a living wage for these workers will ensure a decent wage that supports their families

and helps stabilize the workforce caring for frail elders and people with disabilities in nursing homes across

the Commonwealth. Similar to Governor Charlie Baker’s commitment to providing a $15 per hour starting

wage for Personal Care Attendants (PCAs) in 2018, MassHealth should establish a pathway to a living wage

for nursing home CNAs and ancillary staff.

The state should develop a multi-year strategy that utilizes an annual wage pass-through that both

incrementally raises wages in a signicant manner and takes into consideration the regional wage variation

that exist in the state. To ensure continued progress, it should create a mechanism to enable the state to

fund yearly wage updates consistent with the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Page 13

Support a Culture of Retention

In January 2015, the Health Workforce Research Center on Long-Term Care at the University of California

San Francisco recommended increasing national and state investments in education and training as a

means to improve direct care worker recruitment and retention. Both the Institute of Medicine (2004)

and Massachusetts ECCLI ndings indicate supervisory training positively impacts job satisfaction, feelings

of respect and value and overall retention rates for all direct care workers. Training nurse managers to

become better supervisors and leaders is necessary to create an organizational culture of retention for

all staff.

The state should support the rollout and implementation of comprehensive evidence-based supervisory

training for the express purpose of retaining staff and reducing turnover. Using a train-the-trainer model,

employers will increase the knowledge, skills and attitudes managers need to support staff stability and

reduce turnover, foundationally supporting this key component of quality jobs.

Establish a CNA Scholarship Program

Throughout the state, a signicant number of individuals, including nursing home ancillary staff (dietary,

laundry and housekeeping), aspire to become CNAs but do not have the language or literacy skills

necessary to enter into a training program. Many work multiple jobs while attending ABE or ESL programs

to improve their English and numeracy skills. Their progress is typically measured in years. To increase the

supply of CNAs, it is recommended the state fund a CNA Scholarship Program that supports more adults

in their quest for post-secondary credentials by providing integrated ABE/ESL with CNA training. The

Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training (I-BEST) is a national model developed in Washington state

that accelerates the pathway to higher level employment by bridging technical skills and language literacy

teaching. Scholarship funds should be used to offset the cost of training as well as provide stipends to adult

learners so they can reduce the number of work hours to concentrate on completing the I-BEST program

in an expedited amount of time.

Page 14

Sources

American Health Care Association, (2009). Improving Staff Satisfaction: What Nursing Home Leaders are Doing.

Retrieved from http://www.ahcancal.org/facility_operations/workforce/documents/staffsatisfaction.pdf

Barbarotta, Linda. (2010). Direct Care Worker Retention: Strategies for Success. Institute for the Future of

Aging Services. Retrieved from http://www.leadingage.org/uploadedFiles/Content/About/Center_for_Applied_

Research/Publications_and_Products/Direct%20Care%20Workers%20Report%20%20FINAL%20(2).pdf

Castle, Nicholas G, and John Engberg, (2007) “The Inuence of Stafng Characteristics on Quality of Care in

Nursing Homes.” Health Services Research 42.5 (2007): 1822–1847.

Child Care Aware, (2014). Parents and the High Cost of Childcare: 2014 Report. Retrieved from http://www.usa.

childcareaware.org/advocacy/reports-research/costofcare/

CliftonLarsonAllen LLP, (2012). Mapping the Future: Estimating Massachusetts Aging-Services Needs 2010-2030.

Commissioned by the Massachusetts Senior Care Association.

Crittenton Women’s Union, (2013). Economic Independence Calculator. Accessed from website on November

5, 2015. http://www.liveworkthrive.org/research_and_tools/economic_independence_calculator

Dawson, Steven L., and Rick Surpin, (2001). Direct Care Healthcare Workforce: The unnecessary crisis in long

term care. Aspen Institute.

Dill, Janette S.; Morgan, Jennifer Craft; & Kalleberg, Arne L., (2012). Making Bad Jobs Better: The Case of Frontline

Health Care Workers. In Warhurst, Chris, Carre, Françoise, Findlay, Patricia, Tilly, Chris, Lloyd, Caroline, Smith,

Chris & Warhurst, Chris (Eds.), Are Bad Jobs Inevitable?: Trends, Determinants and Responses to Job Quality in

the Twenty-First Century (pp. 110-27). New York: Palgrave.

Eaton, Susan, et al., (2001). Extended Care Career Ladder Initiative (ECCLI): Baseline Evaluation Report of a

Massachusetts Nursing Home Initiative. Harvard Business School.

Frogner, B. and Spetz, J., (2015). Entry and Exit of Workers in Long-Term Care. San Francisco, CA: UCSF Health

Workforce Research Center on Long-Term Care. Retrieved from: http://healthworkforce.ucsf.edu/sites/

healthworkforce.ucsf.edu/les/Report-Entry_and_Exit_of_Workers_in_Long-Term_Care.pdf

Heineman, Janice M, et al., (2007). The Qualitative Evaluation of ECCLI. Commonwealth Corporation Research

and Evaluation Brief, volume 5, issue 2. Retrieved from http://www.leadingage.org/uploadedFiles/Content/About/

Center_for_Applied_Research/Publications_and_Products/ECCLI_Qualititative_Brief.pdf

Institute for the Future of Aging Services, (2007). Extended Care Career Ladder Initiative (ECCLI) Qualitative

Evaluation Project Final Report. Prepared for Commonwealth Corporation. Retrieved from http://www.

leadingage.org/uploadedFiles/Content/About/Center_for_Applied_Research/Center_for_Applied_Research_

Initiatives/ECCLI_Final_Report.pdf

Institute for the Future of Aging Services, (January 2007). The Long-Term Care Workforce: Can the Crisis Be

Fixed? Retrieved from http://phinational.org/research-reports/long-term-care-workforce-can-crisis-be-xed

Page 15

Institute of Medicine, (2008). Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Healthcare Workforce. Retrieved

from http://iom.nationalacademies.org/en/Reports/2008/Retooling-for-an-Aging-America-Building-the-Health-

Care-Workforce.aspx

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, (2007). Nursing Home Survey Results.

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, (2015). Nursing Assistant Program Analysis.

Massachusetts Senior Care Association, (2000-2015). Annual Employer Wage Survey Results. Waltham,

Massachusetts.

National Low Income Housing Coalition. Retrieved from report entitled: Out of Reach 2013.

National Research Corporation, (2012). 2011-12 National Survey on Customer and Employee Satisfaction

in Nursing Homes. Retrieved from http://www.ahcancal.org/research_data/stafng/documents/snf_

nationalreport2012.pdf

PHI PolicyWorks, (2015). Paying the Price: How Poverty Wages Undermine Home Care in America. Retrieved

from www.PHInational.org/payingtheprice

PHI and Institute for the Future of Aging Services, (2003). State Wage Pass-Through Legislation: An Analysis.

Workforce Strategies, no. 1. Retrieved from http://phinational.org/research-reports/state-wage-pass-through-

legislation-analysis

Plumb, Scott, (2001). Where Will Your Mother Go?: A special report on the crisis engulng nursing homes in

Massachusetts and its implications for the care of our frail elders and disabled citizens. Massachusetts Extended

Care Federation.

Seavey, Dorie, (2004). Better Jobs Better Care Practice Policy Report: The Cost of Frontline Turnover in Long-

Term Care. Retrieved from http://phinational.org/research-reports/cost-frontline-turnover-long-term-care

Stone, Robin I., (2008). The Origins of Better Jobs Better Care. The Gerontologist. Vol 48. Special Issue 1, 5-13.

United States Census Bureau, (2010). American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/

acs/data.html

Wilson, Randall, (2006). Invisible No Longer: Advancing the Entry-level Workforce in Health Care. Jobs for the

Future. Retrieved from http://www.jff.org/publications/invisible-no-longer-advancing-entry-level-workforce-health-

care

Zacker, Heather B., (2011). Jobs to Careers Practice Brief: Creating Career Pathways for Frontline Health Care

Workers. Retrieved from http://www.jff.org/sites/default/les/publications/J2C_CareerPathways_011011.pdf

Page 16

Appendix

2015 Median Hourly Wages by County

Source: Mass Senior Care Association Annual Employment Survey, 2015

800 South Street, Suite 280, Waltham, MA 02453

Tel: 617.558.0202 Fax: 617.558.3546 1.800.CARE FOR

www.maseniorcare.org