Indiana Renewable Energy

Community Planning Survey and

Ordinance Inventory Summary

Tamara M. Ogle

Regional Educator

Purdue Extension Community Development

togle@purdue.edu

Kara Salazar

AICP, CC-P, LEED AP ND, NGICP, PCED

Assistant Program Leader and Extension

Specialist for Sustainable Communies

Purdue Extension

Illinois – Indiana Sea Grant

Purdue University Department of Forestry and

Natural Resources

salazark@purdue.edu

Acknowledgments

Sponsor

The authors thank Hoosiers for Renewables and Indiana Farm Bureau for their support of this

research project. We also thank Dr. Sarah Banas-Mills, Darrin Jacobs, and Steve Yoder for their expert

review and feedback. We appreciate the me and contribuons from municipal and county planning

departments and plan commissions from across the state that made the report possible.

3

Background

In 2021, Purdue Extension conducted a comprehensive

overview study of land use regulaons for wind and

solar energy. Purdue Extension's Land Use Team

plays a crical role across Indiana through the work

of Agriculture & Natural Resources Educators serving

on Advisory and Area Plan Commissions either as

vong or advisory members. Team members also

serve as Community Development Educators, faculty,

and specialists working on land use issues. The Land

Use Team's primary purpose is to develop and deliver

educaonal resources to assist Plan Commissions and

other related instuons and organizaons in making

informed land use planning decisions.

The Purdue Land Use Team idened a state-

wide need for research-based technical assistance

informaon focusing on local renewable energy and

land use decision making, specically for ordinance

development. Mulple feedback mechanisms

informed the needs assessment and ordinance

inventory study design. These included feedback

survey results from the 2019 and 2021 Indiana Land

Use Summits, listening sessions with Indiana Land

Resource Council members and stakeholders, Purdue

Extension Land Use Team advisory board members,

and feedback collected during Purdue Extension land

use planning program eorts.

This report provides a summary and snapshot of

state-wide renewable energy ordinances and the

accompanying inventory study. It is divided into the

following secons:

• Introducon and overview of renewable energy

planning and zoning in Indiana

• Study methods

• Summary of community percepons

• Inventory of zoning ordinances

• Appendices

o Survey instrument

o How to read the snapshots

o County snapshots

The report summaries and county snapshots can

be used as a reference for plan directors and plan

commission members to compare other renewable

energy zoning ordinances and zoning tools used

in counes across Indiana. Plan commissions can

dra ordinances that eecvely address concerns

and development goals of the community based on

dialogue between counes and with local stakeholders.

Furthermore, this report should be used for

educaonal purposes only and should be adapted

to each community's local context, as appropriate.

The informaon is not intended to provide specic

recommendaons for policies or decisions.

Addionally, communies connually update

ordinances based on new technology and local needs.

4

Introducon and Overview

Indiana communies are faced with complex decisions

related to land use planning, parcularly for renewable

energy. This complexity and the unique characteriscs

of each community result in a patchwork of land use

policies across the state. Addionally, many local

communies are experiencing an increased interest

in solar due to federal, state, and ulity incenves

(SUFG, 2021). Based on local decisions, some Indiana

communies embrace wind and solar renewable

energy as a part of their land use policies, while

others restrict their development. This is a theme

occurring across the United States as renewable

energy producon increases (Ahani & Dadashpoor,

2021; Milbrandt et al., 2014; Sward et al., 2021). This

increased interest in renewable energy, especially

the sing of wind turbines and solar elds across the

state, has highlighted a gap in research-based land

use planning and technical assistance informaon for

Indiana plan commissions and local government sta.

According to the U.S. Energy Informaon

Administraon, Indiana ranks 12th in the United

States in total energy use per capita due, in part, to

weather extremes. The state consumes approximately

three mes the amount of energy it generates, with

the industrial sector accounng for one-half of energy

consumpon, transportaon and residenal using

one-h of the state's energy, and commercial users

comprising the rest of energy consumpon (US EIA,

2021a). In Indiana, renewable energy generaon has

increased with ulity-scale projects connecng to the

main transmission grid. Indiana began the process for

wind development in 2005 with the rst 1,036 MW of

wind capacity installed by the end of 2009 (Tegen et

al., 2014). In 2020, wind contributed 7% of the state's

electricity net generaon with 2,940 megawas (MW)

of wind capacity state-wide (US EIA, 2021a). Currently,

there is a similar amount of wind development

proposed in the interconnecon queue (3,631 MW)

as was installed at the end of 2020 (2,940MW) (US

EIA, 2021b; MISO, 2022; PJM, 2022). Solar currently

contributes approximately 2% of the state's electricity

net generaon, mostly from ulity-scale facilies

found throughout Indiana (US EIA, 2021; SUFG,

2021). There is approximately 146 mes more solar

development proposed in the interconnecon queue

(40,979 MW) as was installed at the end of 2020 (279

MW) (US EIA, 2021b; MISO, 2022; PJM, 2022). While

not all proposed renewable energy development

within the queue will be built, it indicates increasing

interest in renewable energy development in Indiana.

Inventories of state-wide solar and wind projects can

be found through the State Ulity Forecasng Group's

2021 Indiana Renewable Energy Resources Study:

https://www.purdue.edu/discoverypark/sufg/docs/

publications/2021%20Indiana%20Renewable%20

Resources%20Report.pdf. Addionally, Hoosiers

for Renewables maintains a map of operaonal

and proposed solar and wind projects throughout

Indiana: www.hoosiersforrenewables.com/indiana-

renewable-energy-map.

There are three types of electric ulies in Indiana,

investor-owned ulies, municipal ulies, and rural

electric membership cooperaves (REMCs). Investor-

owned ulies serve the majority of the state and

are divided into ve service territories. Investor-

owned ulies generate power, transmit electricity,

and distribute to customers. There are 72 municipal

ulies across the state, with several of these

represented by the Indiana Municipal Power Agency

(IMPA). IMPA is a wholesale power provider which sells

electricity to its members. IMPA communies can also

develop their own renewable energy projects directly

distributed to customers. REMCs include two primary

generaon cooperave organizaons in the state. The

cooperaves generate and transmit electricity from

facilies across Indiana and deliver it to customers in

their service areas. (OED, 2022).

State-Level Renewable Energy Policy

The Indiana Oce of Energy Development plans and

coordinates state energy policies and administers

grant programs funded by the U.S. Department of

Energy (OED, 2022). Addionally, the Indiana Ulity

Regulatory Commission (Commission) oversees

ulies that operate in Indiana for electric, natural

gas, steam, water, and wastewater (IURC, 2022). The

Commission approved the voluntary clean energy

porolio standard program, which outlines that ulity

companies choosing to parcipate need to acquire

10% of electricity from clean energy sources by

2025. Ulies also need to provide net metering for

customers generang renewable energy of less than

5

1 MW of capacity (US EIA, 2021; IOUCC, 2022; IURC,

2022). For example, the average capacity for a wind

turbine built in 2020 was 2.7 MW, and 1 MW of solar

panels covers approximately 4-7 acres (EERE, 2021).

Addionally, renewable energy projects require a

Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) to contract supply

with a ulity company when generang more than 1

MW of capacity and more than the annual average

electricity consumpon (Marn, 2021).

Zoning Provisions for Local Renewable Energy

Planning and Development

While state agencies guide policies and ulity

regulaons, oversight of renewable energy

development and land use planning processes

currently occurs locally. Eighty-two of Indiana's 92

counes (89.1%) have adopted both planning and

zoning. These zoning ordinances govern land use in

the unincorporated areas of these counes and in

some municipalies where area planning has been

adopted by the county and one or more cies or towns

within the county. Counes can create standards and

processes through the zoning ordinance to regulate

their jurisdicon's land use and development.

Counes create zoning districts and specify the

permied uses within that district. Uses can be

classied as permied by right, permied by special

excepon (somemes referred to as special uses or

condional uses), or not permied. Permied uses

can apply for improvement locaon permits through

the planning oce and must follow all district and

use standards. However, they do not require approval

from the plan commission or board of zoning appeals

(BZA).

The BZA must approve a use permied by special

excepon (IC 36-7-4-918.2). This requires a public

hearing and allows the county to review the details

and parcular applicaon and parcel to ensure

the development will be compable with their

comprehensive plan and zoning ordinance. Criteria

for approving special excepons are set in the zoning

ordinance, which can be general or specic for a

parcular use. Special excepons must also adhere to

any zoning district or use standards.

If a use is not permied in a district, the peoner may

apply for an amendment to the zoning map, commonly

referred to as rezoning. Rezoning requires a public

hearing before the plan commission, which gives either

a favorable, unfavorable, or no recommendaon to

the legislave body. The legislave body then votes

to approve or deny the rezone (IC 36-7-4-607). In a

jurisdicon under advisory planning law, an applicant

seeking to develop a use that is not permied in their

zoning district could also pursue a use variance from

the board of zoning appeals.

Overlay districts are another zoning tool used to

regulate commercial renewable energy development.

Overlay districts are layered on top of the exisng

zoning district. The current or underlying zoning

districts standards apply to all development. In

addion, the overlay district standards apply to uses

that are permied in the overlay district but not the

underlying district. An overlay district for renewable

energy can be applied proacvely to guide renewable

energy development to preferred areas (Beyea, 2021).

If the community establishes an overlay without

proacvely applying it to the zoning map, an applicant

may have to go through the rezoning process to put

the overlay district in place before applying for a

permit for a commercial renewable energy system.

Development is primarily regulated through

developmental standards in the zoning ordinance.

Each zoning district will have developmental standards

that apply to all uses within that district. In addion,

zoning ordinances can also create standards specic to

certain uses or use standards. Commonly these dene

a buer or separaon between the use and another

conicng land use, addional setbacks, height

restricons, and various other standards to regulate

the look and impact of the use on the surrounding

property. If an applicant cannot meet one or more

of the standards, they can seek a variance from

developmental standards from the board of zoning

appeals.

The zoning ordinance may also require dierent

plans submied or studies conducted to permit

commercial renewable energy. This includes but is

not limited to economic development agreements,

maintenance plans, and transportaon plans. These

plans can be an addional part of the process or

something already required by other agencies that

the planning oce wants to see to determine if other

6

regulaons are being followed. A site plan or scaled

drawing of the development is generally required for

any improvement locaon permit so that planning

sta can ensure standards will be met. Some zoning

ordinances may require a specic use to go through

a development plan review. This process will be

delineated in the zoning ordinance and may be done

by sta, a commiee, or the plan commission.

Solar Energy Development

The following 36-month example meline outlines

the solar sing and development process (Hoosiers

for Renewables, personal communicaon, December

2021). The general outline below is a snapshot of

milestones and overarching melines. Delays and

updates can occur within each step, which could

extend the meline. For example, although the

project is sll underway, a step could be stalled with

no visible progress pausing the meline. Several

risks and unknowns can extend the meline, such as

compleng and receiving reports back from ulity

companies, availability and transportaon costs

of materials, labor costs, and market demands.

Addionally, solar developers have to post leers

of credit at key milestones. A meline may need to

be restarted if there are too many changing aspects

related to the development.

• Determine potenal sites with transmission access & capacity

• Sign contracts with landowner(s)

• File for interconnecon

• Preliminary due diligence and site inspecons

• Receive interconnecon feasibility report

• Finalize land control

• Begin full site analysis

• Begin county, state, and federal perming process

• Begin negoaons with investors

• Receive interconnecon system impact report

• Finalize project meline

• Complete perming process

• Finalize negoaons with investors

• Execute interconnecon agreement

• Choose contractors for site construcon

FINAL STEPS

• Construcon generally runs 12 – 24 months

• Project comes online

7

The community development process for solar energy projects also includes communicaon between the

renewable energy development company and county government planning and zoning, outreach with

landowners, local businesses, and community members.

Wind Energy Development

Wind energy development is also a long-term process. There are several phases that local government ocials

and community members should ancipate as part the wind energy development process (Constan & Beltron,

2006; Marn, 2021). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service example, "Lifecycle of a Wind Energy Facility," from

Marn (2015) describes the following meline of wind energy from prospecng through decommissioning. The

melines from prospecng through operaon can be extended or stopped due to several factors, including

perming, zoning, and market factors, among others.

PROSPECTING

• Idenfy site

• Collect wind data

• Idenfy project boundary

• Coordinate land lease agreements with landowners

• Conduct environmental and feasibility assessments Idenfy routes for trans-

mission lines

• Create design map of turbine locaons

DEVELOPMENT

• Conduct evaluaon of project design and plan with interdisciplinary team

• Finalize perming and approvals at federal, state, local levels

• Receive Condional Use Permit or Land Use Permit (LUP) from local

government for project

CONSTRUCTION/

COMMISSIONING

• Grading plan and earthwork

• Construcon of electric cables from turbines to substaon

• Road construcon

• Construct turbine pads

• Transmission line construcon

• Permanent met-towers constructed

• Assemble turbine towers and generators

• Substaon construcon

OPERATION

• Wind energy project monitored and managed daily

DECOMMISSIONING

• Decommission wind farm

• Sell parts for scrap

• Opon to repower with new technology

8

Methods

This project focused on the following queson to

understand local planning policies for renewable

energy.

What types of land use policies and strategies have

Indiana communies adopted to plan for renewable

energy?

Electronic surveys were sent to 161 contacts of Indiana

county and municipal planning departments and plan

commissions in the summer of 2021. The survey was

open for six weeks from May-June 2021 and sent

through mulple modes, including direct emails and

listservs such as the American Planning Associaon,

Indiana chapter. There were 84 survey responses with

a 52% response rate.

The survey was used to idenfy provisions in zoning

ordinances specic to climate change and renewable

energy, factors considered when adopng or rejecng

policies, and the level of public parcipaon and

conict. Respondents were also asked to link or upload

content from wind and solar ordinances and zoning

maps for the inventory. Ordinances were collected

through the survey and direct county contacts from

summer 2021 through winter 2022 and coded to

idenfy common aributes of climate change and

renewable energy land use policies to compare

dierent local policies and summarize to create

county snapshots. The study focused on commercial

solar and wind development and looked at zoning

ordinances for unincorporated areas that regulate

these as unique uses.

This study draws from the methodology used by

Ebner (2015) to inventory land use regulaons of

conned feeding operaons. Ordinance provisions

for commercial solar and wind were divided into four

categories:

• districts and approval process;

• buers and setbacks;

• other use standards; and

• plans and studies required.

This study uses similar categories to Ebner (2015)

to categorize the dierent review and approval

methods for CWECSs and CSESs: permied use,

permied use with addional use standards, special

excepon, rezoning required, and rezoning required

and special excepon. This study adds a category:

overlay district. Several counes use overlay districts

to regulate commercial renewable energy systems. In

these counes, parcels would need to be rezoned to

include the overlay district; standards for the overlay

district and underlying zoning district would apply to

the development. Counes can have dierent permit

processes for use depending on the district. For this

study, counes are categorized based on the process

required of CSESs and CWECSs for land currently

zoned agricultural. The categories specify the process

required, not the diculty level in sing a commercial

renewable energy system.

Standards that are easily quaned, like buers and

setbacks, are classied and compared. However, for

more descripve use standards and plans and studies

required, this study uses a binary approach of whether

such provisions are included in the ordinance or not.

Summary of Community Percepons

Community percepon quesons of renewable

energy included topics related to types of conict

and conict resoluon, factors inuencing policy

changes, and resources needed to make informed

decisions about renewable energy planning. Out of

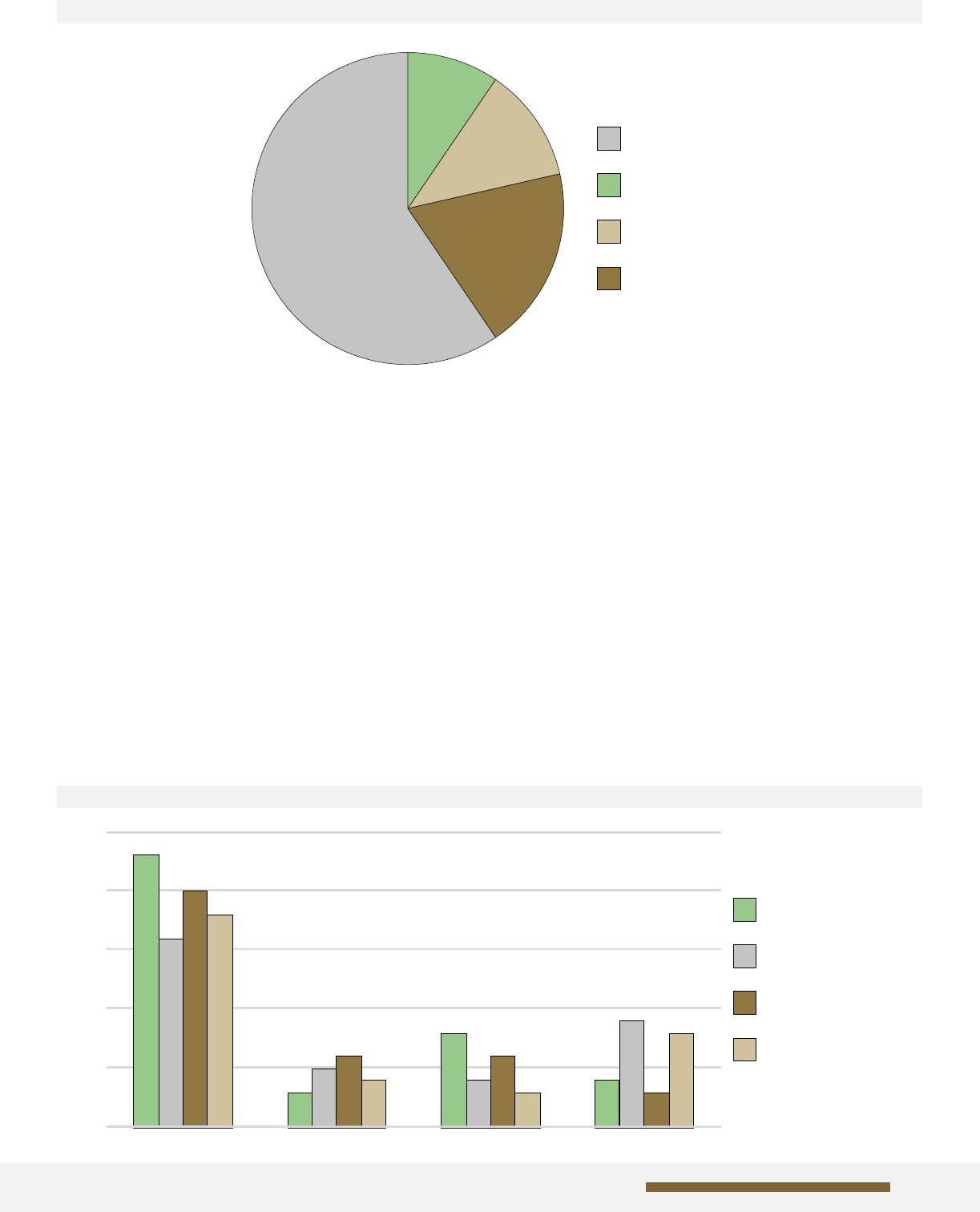

the 84 responses for community planning aliaons,

50 represented county government, 16 mul-

governmental units, 10 towns, and eight cies (Figure

1). Respondents addionally represented 49 advisory

plan commissions, 33 area plan commissions, and two

metro plan commissions.

9

Community planning representaves responded (n=41) with the extent that renewable energy regulaon acvies

for solar ordinances, wind ordinances, solar development, and wind development resulted in conicts over the

last ve years (Figure 2). No conicts were idened with 23 community solar ordinances, 16 wind ordinances,

20 solar development projects, and 18 wind development projects. Fieen communies experienced solar

ordinance eorts resulng in conict, while the process of developing wind ordinances also resulted in conict

in 18 communies. Solar and wind development eorts iniated conicts in 15 communies each. Communies

that experienced some level of conict (very lile, somewhat, to a great extent) were asked to respond to

how conict was resolved (or not) through policy changes (n=12) or facilitated discussions (n=11) (Figures 3

and 4). Community conicts resulted in changing policies with eight solar ordinances, 11 wind ordinances, four

solar development projects, and seven wind development projects. Facilitated forums or community discussions

were used in six communies for solar ordinance development, seven with wind ordinances, two with solar

development, and ve with wind development projects. For communies that did not have a nal agreement

or policy change for renewable energy regulaons, work is in progress or stalled. For example, a county wind

ordinance eort resulted in a moratorium on wind development projects. In another county example, wind

development projects are stalled due to the plan commission and wind company not reaching an agreement for

road use or economic development.

Figure 1: Type of government unit aliaon for community planning

Figure 2: Renewable energy regulaon acvies resulng in community conicts within the last ve years

Community Responses

0

5

10

15

20

25

Not at all Very lile Somewhat To a great extent

50 (60%)

County

City

Town

Mul-governmental

Solar Ordinances

Wind Ordinances

Solar Development

Wind Development

8 (9%)

10 (12%)

16 (19%)

Respondents (n=49) rated factors that inuenced changes to renewable energy regulaons/ordinances over

the last ve years from 1 = did not inuence at all to 10 = greatly inuenced (Figure 5). Several factors did

not inuence changes to regulaons. Concerns from neighbors (n=34) was the most frequently selected, with

34.29% indicang the factor greatly inuenced changes. Concerns about climate change (n=18) and concerns

about energy availability (n=19) were selected with over 60% indicang this factor did not inuence changes

in regulaons or ordinances. Other responses not listed included adding solar to a joint zoning ordinance,

receiving a sol smart award to modernize solar ordinances, and including larger setbacks from non-parcipang

landowners.

Figure 3: Community conict leading to renewable energy policy changes in community

Figure 4: Facilitated forums or discussions used for renewable energy policy agreements

Solar Ordinances

Wind Ordinances

Solar Development

Wind Development

Solar Ordinances

Wind Ordinances

Solar Development

Wind Development

Yes

Yes

No

No

I don't know

I don't know

Community ResponsesCommunity Responses

0

0

2

1

4

2

6

3

8

4

10

5

7

12

6

8

11

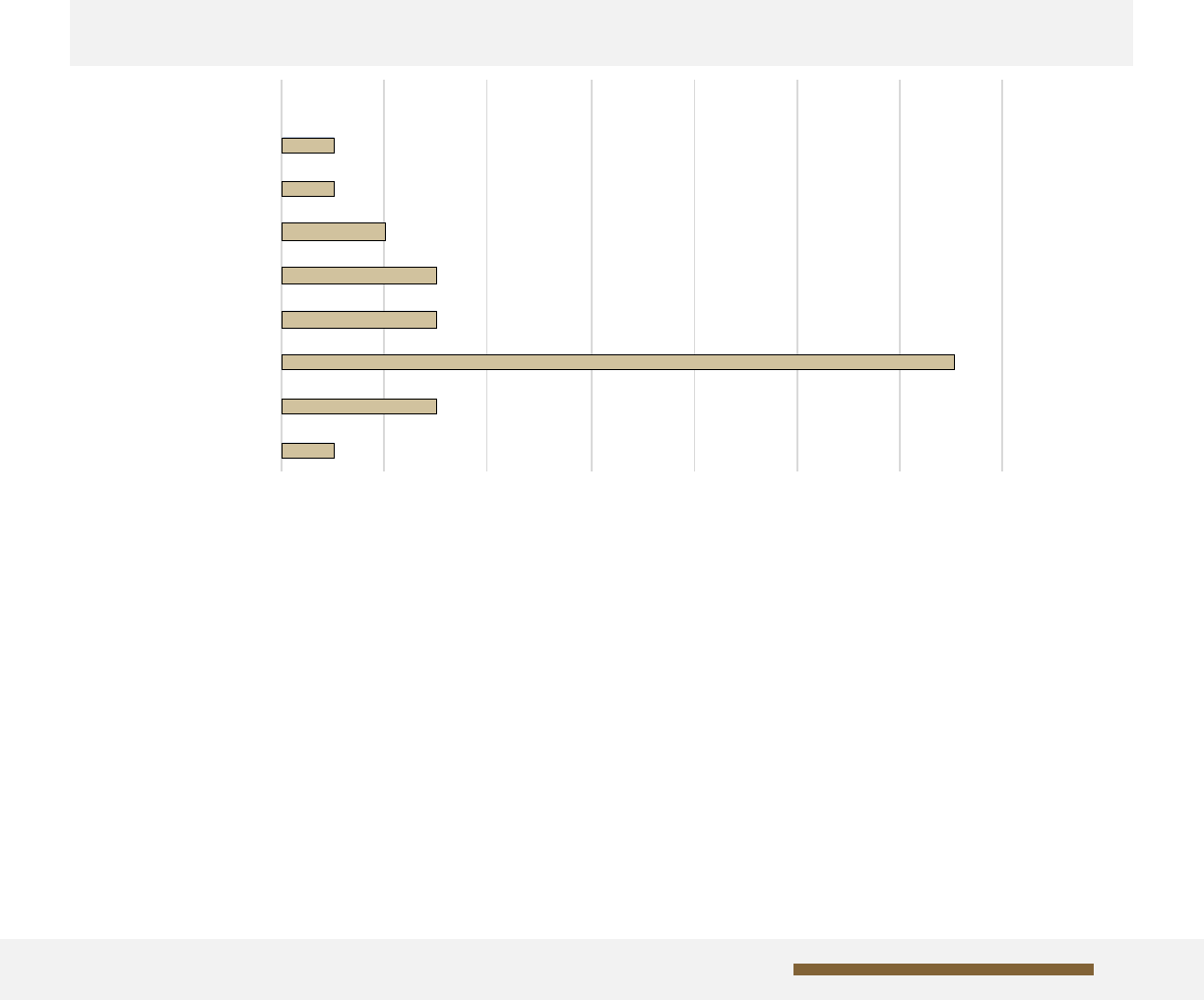

The types of informaon community planning representaves need to help make decisions when developing

or amending renewable energy regulaons/ordinances (n=47) was split in frequency between the two ends of

a scale from not needed to greatly needed (Figure 6). The impact on property values had a higher frequency

(n=46; 26.09%) selected as a need for more informaon over all other informaon types. Conict management

received the lowest selecon for need (n=43; 23.26%).

Figure 6: Types of informaon needed to make renewable energy regulaon/ordinance decisions

Figure 5: Factors inuencing changes to renewable energy regulaons/ordinances in the last ve years.

0% 1 0% 2 0% 3 0% 4 0% 50% 6 0% 7 0% 8 0% 9 0% 100%

Other

Concerns from neighbors

Aesthetics

Concerns about property values

Loss of farmland

Economic development opportunities

Concerns about fiscal impact to the county

Co nce rns ab ou t nois e

Proposal for new or expansion of existing development

Co nce rns ab ou t pub lic he alth

Routine zoning ordinance update

Concerns about energy availability

Concerns about climate change

1 = did not influence 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 = greatly influenced

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Impact on public health

Impact on property values

Impact on environment

Impact on aesthetics/view

Fiscal impact to the county

Energy reliability

Co nf lic t ma na geme n t

1 = not needed 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 = greatly needed

12

Overview of Zoning Provisions Used to Regulate CWECSs and CSESs in Indiana

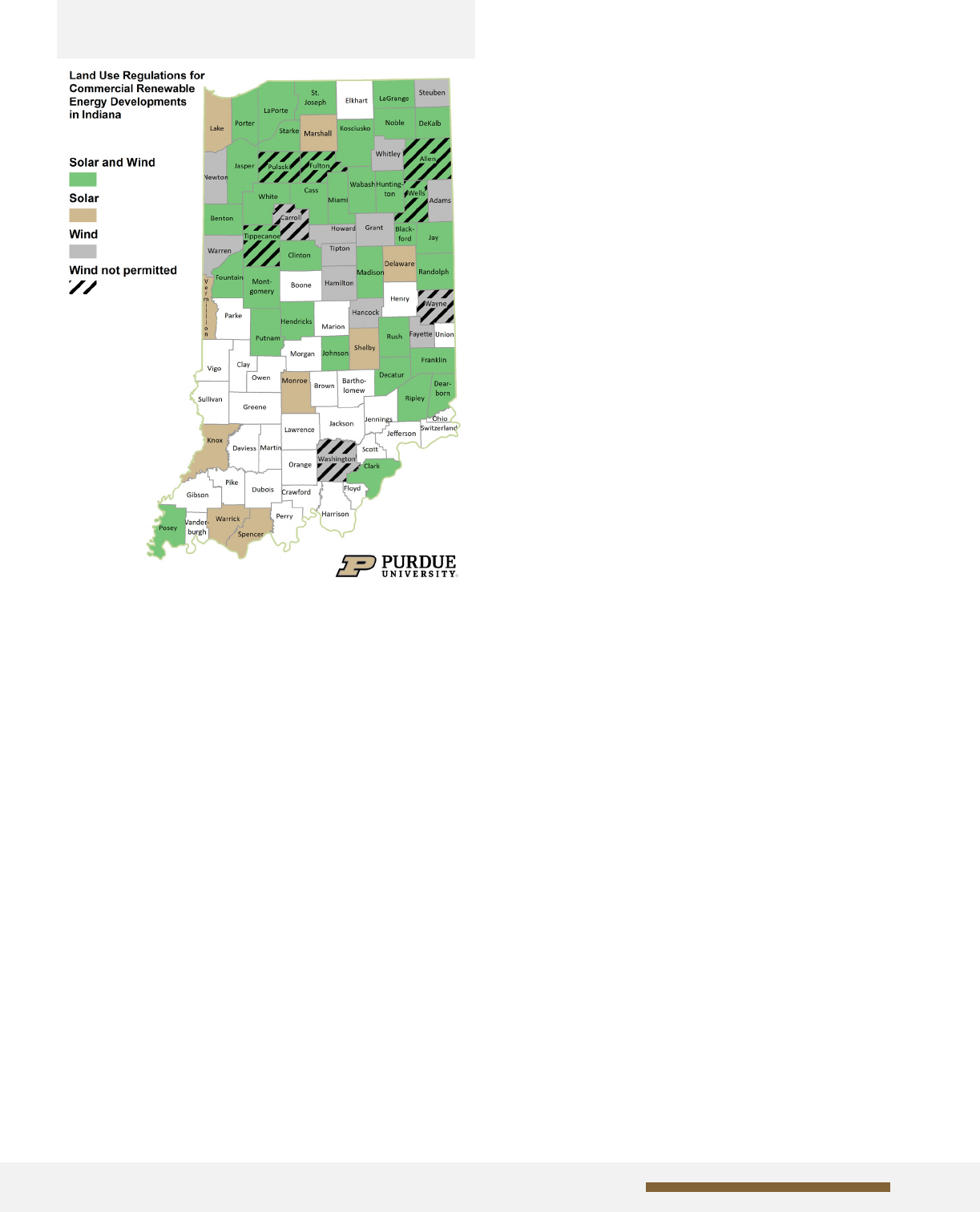

Of the 82 counes with planning and zoning, this study idened 46 (56.1%) county zoning ordinances with

standards specic to commercial solar energy systems and 51 (62.2%) with standards specic to commercial

wind energy conversion systems. Eight of these counes currently do not permit commercial wind in any zoning

districts. The ordinances vary in the tools they use to regulate renewable energy and even in how they dene

commercial solar and commercial wind as uses. The ndings organize and compare commercial solar and wind

regulaons within the following four categories:

• districts and approval process;

• buers and setbacks;

• other use standards; and

• plans and studies required.

Informaon used to support decision-making for local renewable energy regulaon and planning is found from

mulple sources by local planning sta (n=54). Planning organizaons (n=43), colleagues and peers (n=39), state

government agencies (n=33), cizen groups (n=31), and cooperave extension (n=31) were frequently selected

opons. Other sources (n=5) listed examples of peer communies and renewable energy industry companies

with popular press (n=8) and social media (n=5) selected among the least (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Sources of informaon used to make decisions for developing renewable energy regulaons

ordinances

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Pl annin g organizat io ns

Colleagues and peers

State government agences

Citizen groups

Cooperative Extension

Federal government agencies

Universities

Consultants

Environmental organizations

Popular press

Other

So cial Media

Community Responses

13

Use Denions and Zoning District

This study looks specically at ordinances regulang

commercial wind and solar operaons. Each

jurisdicon can set its own denion for these

uses. Some counes dierenate commercial solar

energy systems (CSESs) and commercial wind energy

conversion systems (CWECs) from small-scale or

personal renewable energy systems.

Use Denions for CSESs

Twenty-seven of the 46 counes (58.7%) that regulate

CSESs dene them by how the power produced is used.

Common phrases include: "primarily for o-site ulity

grid use,” "delivers electricity to a ulity's transmission

lines," and "primary purpose of wholesale or retail sale

of generated electricity." Thirteen counes (28.3%)

dene CSESs from small-scale systems by their size,

such as lot size, square footage of panels, or electricity

generated. Two counes regulate all SESs similarly,

and one county regulates all ground-mounted SESs

as commercial solar. Two counes have standards for

CSESs but do not have a specic denion for this use

in their ordinance.

Use Denions for CWECSs

Commercial wind denions look similar to their CSES counterparts. Just under half (n=25; 49.0%) of the counes

regulang CWECS dene them by how the power produced is used. These phrases are similar to those seen in

CSES denions, including: "primarily for o-site ulity grid use,” "delivers electricity to ulity's transmission

lines," and "generates electricity to be sold in retail or wholesale markets." One county regulates all wind

energy conversion systems similarly. Six counes regulate CWECSs but don't dene them. The other 19 counes

(37.3%) use a size criterion to dene commercial systems from others. Common size measures include kilowas

produced, height, and number of towers.

Zoning Districts and Approval Methods

Sixteen counes permit CSESs by right in an agricultural district (Figure 8). Of these counes, Clark County is

the only county that does not require addional use standards. Twenty-three counes permit CSESs by special

excepon in an agricultural district. Seven counes would require rezoning to permit a CSES. Five of these

counes use overlay districts, and one would need a special excepon aer rezoning. While an overlay district

would not require rezoning if the community applied it proacvely, the study did not nd this was the case in

counes with wind or solar overlay districts.

Seven counes permit CWECs by right in an agricultural district with addional use standards. In 24 counes,

CWECs are permied by special excepon. Rezoning would be required in 12 counes. Nine of these counes use

an overlay district. The other three would require both rezoning of agricultural land and special excepon. Eight

of the counes do not permit commercial wind projects in any district. One of these counes, Carroll County,

does not specify any districts in which commercial or non-commercial wind is permied or not permied, but

has adopted use standards for both of these uses. This may have been an oversight in the amendment.

Figure 8: Map of land use regulaons for

commercial renewable energy

developments in Indiana

14

Figure 9: Approval methods for CSESs and CWECSs

a

in general ag districts.

a

Eight counes do not permit wind in any district. These counes are not included in the gure.

Solar

Wind

Permied

by right

Rezoning

Required

Permied

with use

standards

Rezoning

& Special

Excepon

Special

Excepon

Overlay

District

0

5

10

15

20

25

No. of Counes

Figure 10: Number of counes with buer requirements for commercial solar (n=32) and wind

developments (n=34) from various uses

Buers & Setbacks

Buers and setbacks are common tools in zoning

ordinances for developments. Allowing for space

between conicng land uses (or a structure) and

a property line can reduce conict between uses.

This study denes a buer as the required distance

between a use and a diering use, zoning district, or

municipality. A setback is a required space between

a structure and a property line or right of way. While

setbacks are common provisions in zoning district

standards that apply to all structures built in the

district, this secon explores setbacks and buers

specic to commercial wind and commercial solar

energy systems.

Figure 9 shows the number of counes with buer

requirements for CSESs and CWECs from various uses.

Thirty-two of the 46 counes (69.6%) with commercial

solar standards require a buer between a CSES and at

least one other use. Thirty-four of the 44 ordinances

(77.3%) containing standards for CWECSs require a

buer from at least one other use. The seven counes

that do not permit commercial wind in any district

are excluded from the analysis of developmental

standards. Carroll County is included in this analysis

because they do have use standards for CWECs.

Commonly buered uses for wind and solar include

residences, schools, and churches. Buers from

municipalies and conservaon land is also common

for commercial wind developments. Addional

setbacks were found in 33 of the 46 counes (71.7%)

for commercial solar and 37 of the 44 counes (84.1%)

for commercial wind.

Solar

Wind

Residences

Businesses

Cemeteries

Churches

Public Buildings

Conservaon

Land

Schools

Primary

Structures

Residental Zone/

Plaed...

Municipalies

0

5

10

15

20

30

25

35

No. of Counes

15

Buered Uses from Commercial Solar

Twenty-eight of the 46 counes (60.9%) that regulate

commercial solar through their zoning ordinance

have a buer for residences. Required buers from

residences range from 140-660 feet, with a median

of 200 (Figure 10). Wabash County bases its buer on

the size of the CSES site (with a range of 450 for sites

less than 5 acres to 1,320 for sites between 90.1-100

acres). In some ordinances, this buer applies only

to non-parcipang residences or can be waived by

parcipang residences. Dekalb County has a buer

of 400 from residences but allows for a shorter

distance if a landscaping buer is installed. A few

counes specify where the inverter should be located

within the solar energy array.

Five counes specify buers from residenal zones. In

two of these counes (Johnson and Montgomery), this

buer is equal to the county's required buer between

a CSES and residences. It would extend the residenal

buer to property that is zoned or intended for

residenal use but does not currently have a residence

on it. Two other counes (Fountain and White) do not

have specied buers for residences, so residences in

residenal zones would be buered, but residences

outside of residenal zones would not. Randolph

County requires a larger buer for residenal zones

than for individual residences. Finally, two counes

specify a buer for plaed subdivisions: Kosciusko

County at 5,280 and Randolph at 500 .

Figure 11: Range of Buer Requirements () in Zoning Ordinances (n=28)

a

between CSES and

Residenal Uses

b

a

One addional ordinance species a range for the buer requirement based on CSES size. It is not included in this gure.

b

Median: 200 ; mean: 257 .

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14

1 00

1 50

2 00

2 50

3 00

4 00

6 50

6 60

No. of Counties

Buffer (ft)

Three counes require a buer between a CSES and municipalies. Kosciusko and Posey Counes require a

buer of 5,280 from municipalies, while Wabash County requires a buer of 1,320 . Churches and schools

are buered in 10 counes (Table 1). Businesses and public buildings are buered in seven and six counes,

respecvely. Four counes specify buer requirements for all primary structures. Wabash County buers from

businesses, public, and recreaonal uses with the same range as residences. Addionally, one county requires

a buer of 250 from cemeteries, another requires a buer of 500 from airports, and one county requires a

buer from campgrounds.

16

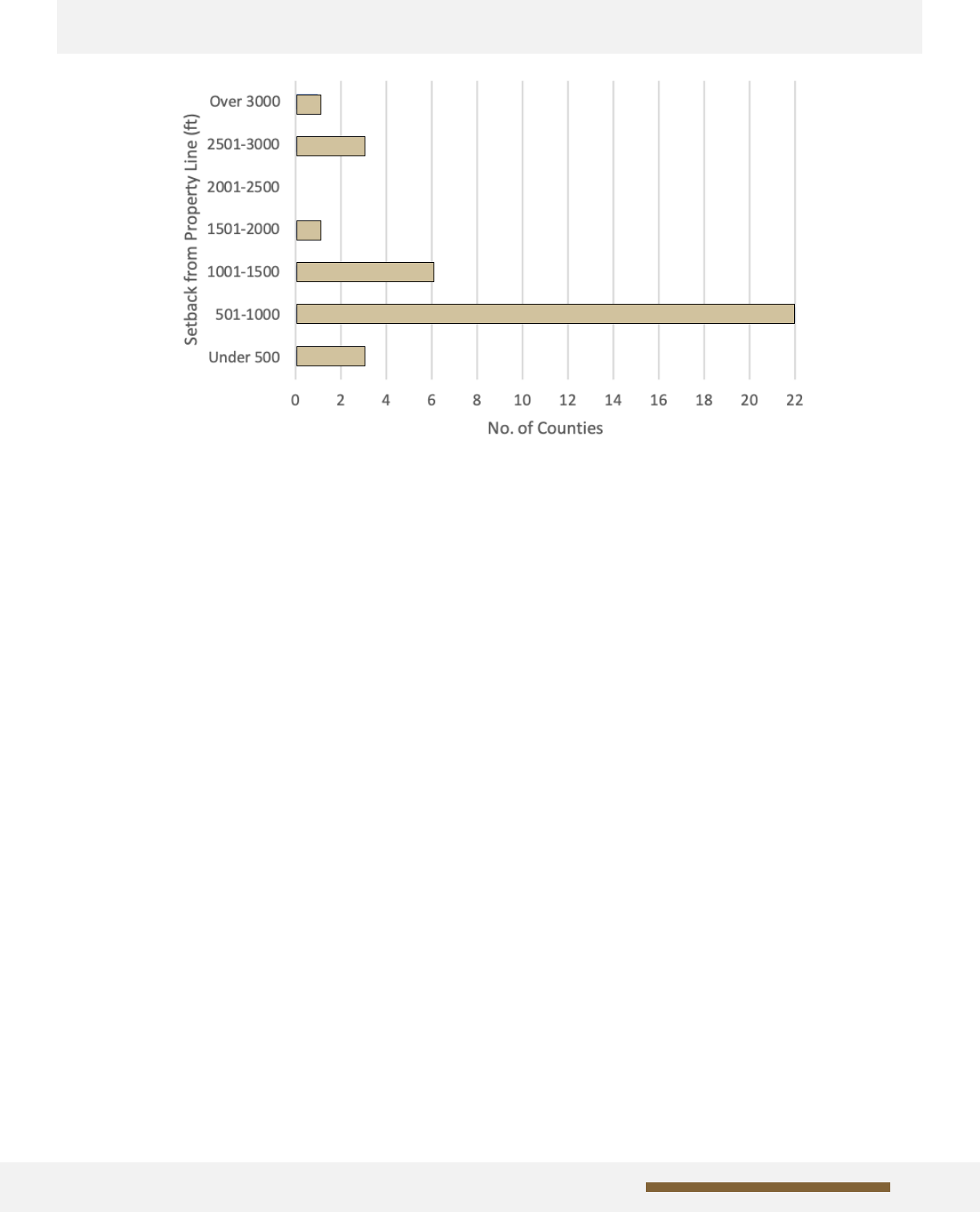

Commercial Solar Energy Systems Setbacks

Thirty-three counes with commercial solar regulaons (71.7%) require setbacks (Figure 11). Setbacks from

property lines (n=31) range from 20 - 330 (median: 50 ; mean: 88 ). Setbacks from the rights of way (n=13)

range from 16.5 to 150 (median: 100 ; mean: 95 ). Two counes specify a setback from just the right of

way, and 20 counes specify a setback from just the property line. Thirteen counes require specic setbacks for

CSESs from rights of way and property lines. Seven of the 13 counes have a higher setback from rights of way,

and four of the 13 counes have a higher setback from the property line.

Figure 12: Setback Requirements () in Zoning Ordinances (n=13) Specifying Standard Setbacks between

CSESs and Adjacent Property Lines (n=31)

b

and Rights of Way (n=13).

c

Table 1: Range of Buer Requirements in Ordinances Requiring Buers between CSESs and Churches,

Schools, Businesses, Public Buildings, and Primary Structures.

b

Median: 50 ; mean: 88 .

c

Median: 100 ; mean 95 .

a

One addional ordinance species a range for the buer requirement based on CSES size. It is not included in this gure.

Number of

Ordinances

Churches

a

9 100-660 200 246

Schools

a

9 100-660 200 246

Businesses

a

7 60-660 200 253

Public Buildings

a

6 100-660 200 268

All Primary Structures 4 200-660 250 340

Property

Line

Right of

Way

16.5

0 63 91 74 102 85

20

25

30

50

100

75

150

60

140

95

200

330

Setback (.)

No. of Counes

17

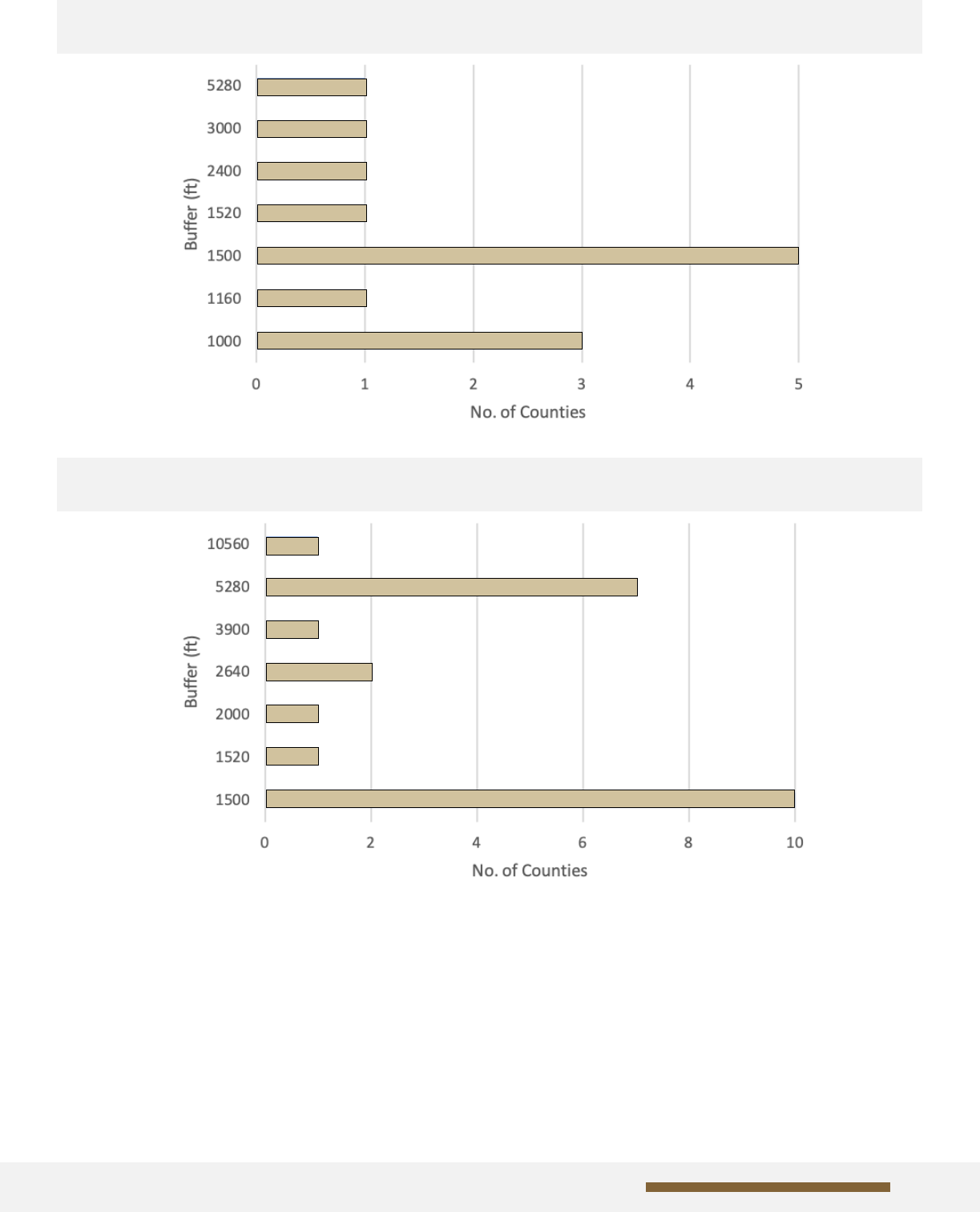

Thirteen counes include a buer from either a residenal zoning district or plaed subdivision ranging from

1,000 to 5,280 feet (Figure 13). In some cases, the buer from a residenal zoning district or plaed subdivision

is the same as the county's buer from residences. This likely provides a buer for planned residenal areas

that have not been developed yet. In other counes, the buer for residenal zones or plaed subdivisions

is greater than for residences. Two counes require a buer from residenal zones and plaed subdivisions

but not all residences. In both situaons, the county may consider residenal zones and plaed subdivisions a

higher intensity residenal use that would benet from a larger buer from commercial wind energy conversion

systems. This also might be why 23 of the 44 counes (52.3%) that regulate commercial wind require a buer

from municipalies. These buers range from 1,500 to two miles (Figure 14).

Buered Uses from Commercial Wind

Residences are a buered use from commercial wind in 30 of the 44 counes (68.2%) with commercial wind

standards. Nine of the 30 counes base the size of the buer on a factor of the wind tower height (e.g., the

buer is 1.1 mes the tower height). Six of these ordinances also include a minimum buer. A wind tower height

of 600 was used to compare residenal buers for the study. According to the USGS, the largest wind towers in

Indiana are 591 tall (Hoen, 2022). Figure 12 shows the range of required buers between residenal dwellings

and wind towers 600 tall.

Figure 13: Range of Buer Requirements () in Zoning Ordinances (n=30) between WECS (600 tall) and

Residenal Uses

a

a

Buers are calculated for towers 600 tall.

18

a

Buers are calculated for towers 600 tall.

Zoning regulaons for commercial wind development also frequently contain buers for schools (n=16, 36.4%),

conservaon land (n=14, 31.8%), and churches (n=12, 27.3%). Several of these are based on wind tower height,

like buers from residences. For this study, a height of 600 feet was used to compare buer requirements across

dierent uses and counes. Buer requirements from schools have the largest range, from 660 feet to two miles,

with a median of 1,630 feet (Table 2). The denion of conservaon lands varies by county. Some counes require

a buer only from federally-owned conservaon land, while others dene the term more broadly. Buers from

conservaon land range from 510-2,640 feet, with a median of 1,125 feet. Addionally, some counes include

buers from specic wildlife areas or rivers in their community. Buer requirements from churches range from

1,000 to 3,960 feet, with a median of 1,500 feet. Other less frequently buered uses include public buildings

(n=11), businesses (n=9), and cemeteries (n=1).

Figure 14: Range of Buer Requirements () in Zoning Ordinances (n=13) between WECS (600 tall) and

Residenal Zones or Plaed Subdivisions

a

Figure 15: Range of Buer Requirements () in Zoning Ordinances (n=23) between WECS (600 tall) and

Municipalies

b

b

Buers are calculated for towers 600 tall.

19

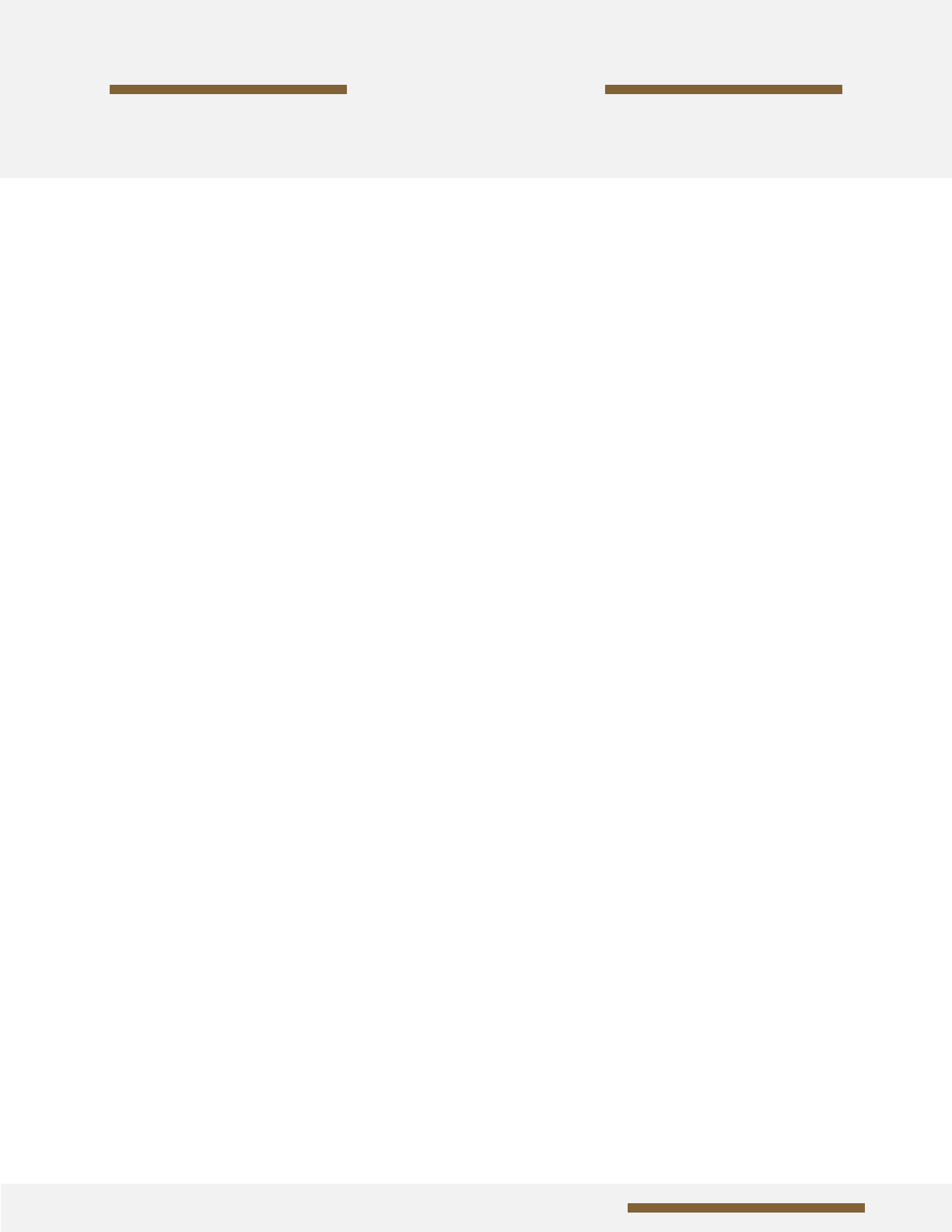

Commercial Wind Energy Conversion System Setbacks

Like use buers, setbacks for CWECSs are frequently calculated based on a factor mulplied by the tower height.

Most counes calculate tower height as the blade's p at its highest point. This would be higher than the hub

height, which is oen used by industry professionals in describing a wind turbine. Figure 15 shows the various

types of setbacks counes employ. Addionally, one county requires the BZA to set the setback of a WECs tower

from a property line within a given range (2,640-3,200 ). Figure 16 shows the distribuon setbacks that would

be required from property lines for 600 wind towers (range: 205 to 3,960 ; median: 660 ; mean: 1,067 ).

Table 2: Range of Buer Requirements in Ordinances Requiring Buers between WECS and Churches,

Schools, Businesses, Public Buildings, and Conservaon Land

a

Figure 16: Types of Setback Requirements in Zoning Ordinances (n=38)

b,c

for WECs

Number of

Ordinances

Churches 12 1,000-3,960 1,500 2,025

Schools 16 660-10,560 1,630 2,794

Businesses 9 660-3,960 1,160 1,631

Public Buildings 11 1,000-3,960 1,500 1,858

Conservaon Land 14 510-2,640 1,125 1,254

b

One county requires that the BZA set the setback from property lines within a given range. This county is not included in this gure.

c

One county requires a setback from interstate ROW in addion to their property line setback. The property line setback is included in this gure, but

the interstate ROW setback is not.

a

Buers are calculated for towers 600 tall.

No. of Counes

0

2

12

4

14

6

16

8

18

10

20

Factor from

Property Line

Factor from

ROW

Set

Measurment

Factor from

Property Line w/

Minimum

Factor from

Property Line w/

Minimum from

ROW

Noise Limits

Several counes regulate noise levels for both

commercial solar and wind. Counes measure sound

levels in a variety of ways. Some counes set a limit

based on decibels (dB), while others use A-weighted

decibels (dBA), a measure of loudness perceived by

human ears. Counes also dier on where the sound

level is measured, such as at the property line or a

nearby structure. Because of these variables, it is

more challenging to compare noise restricons across

the counes.

Noise Limits for Commercial Solar

While solar panels don't create noceable noise, the

equipment necessary for converng solar energy to

electricity, such as invertors, does. Twenty-one of the

46 counes (45.6%) that regulate CSESs have a noise

limit. In 19 of the counes, this is a nite limit (dB or

dBA). This limit ranges from 32 to 60 dBA for the counes

that use the A-weighted measurements(mean: 50.2

dBA; median: 50 dBA). Randolph County uses a range

depending on the adjacent property use, and Posey

County sets a limit of 45 dBA or 5 dBA above the

ambient baseline.

Noise Limits for Commercial Wind

Noise is regulated in 84.1% of the counes (n=37)

with CWECs standards. Like solar, the noise limits

imposed for counes using A-weighted decibels range

from 32-60 dBA (mean: 48.1 dBA; median 50 dBA).

Twenty-two counes use a nite limit. Seven counes

use a range of limits--ve based on the hertz of the

sound produced, and two based on adjacent uses.

The remaining six counes limit how much the noise

produced can exceed the ambient baseline.

Other Common Commercial Solar Standards

Thirty-three counes (71.7%) have a maximum height

restricon for CSESs. Allen County regulates height as

they would an accessory structure. White County uses

a range. Height restricons in the remaining counes

range from 12-35 at maximum lt (mean: 22.6 ;

median 20 ). Less common than height restricons,

Figure 17: Range of Setback Requirements () in Zoning Ordinances (n=37)

a

between WECS (600 tall)

and Residenal Uses

b

a

One county requires the BZA to set the setback of a WECs tower from a property line within a given range. This county is not included in this gure.

b

Range: 205-3,960 ; median: 660 ; mean: 1,067

21

11 counes require a minimum lot size. Five acres is

the minimum lot size in nine of the counes. Warrick

County has a minimum lot size of one acre for CSESs,

and Blackford County requires 10 acres.

Ground cover standards for CSESs are found in 23

ordinances (50.0%). These range from specifying the

use of perennial, noxious-weed-free seed mixes to

requiring the use of nave plants. Eleven of these

counes require pollinator-friendly ground cover.

Several ordinances also contain language in the zoning

ordinance regulang signage and warnings (n=30,

65.2%), fencing (n=36, 78.%), landscaping (n=35,

76.1%), and glare (n=23, 50.0%) for CSESs.

Other Common Commercial Wind Standards

Thirty-eight counes (86.4%) regulate the commercial

wind tower's blade clearance from the ground. Two

counes specify a minimum blade clearance of 50

or one-third of the tower's height. The rest of the

counes have minimum blade clearances ranging from

15 - 75 with a mean of 31 and median of 25 . Only

ten counes regulate the height of commercial wind

towers. Most oen in ordinances, this is measured

by the blade's p in the vercal posion. Maximum

heights allowed range from 200-600 (mean: 430;

median 450).

Twenty-three counes (52.3%) have standards for

shadow icker. Some of these are statements such as

"no shadow icker," while other counes include more

descripve language on what buildings or uses are

to be protected from shadow and how long shadow

icker can occur per day or year. Many counes (n=40,

90.9%) regulate the color of wind towers. The language

is similar across all counes, with non-reecve white

or gray turbines. Some counes specify that blades

can be black to help with deicing. Other common

standards include braking systems (n=34, 77.3%),

signage/warnings (n=36, 81.8%), fencing or climb

prevenon (n=35, 79.5%), interference (n=27, 61.4%)

and lighng (n=23, 52.3%).

Plans and Studies

Requiring dierent plans and studies before approving

a renewable energy project is another tool found in

zoning ordinances. Some of these plans or studies

may be required by other regulatory agencies or an

industry standard, while others are specic to the

county and project. Oen, plans and studies may be

needed for the county to ensure other use standards

will be met.

Decommissioning plans are required in 40 counes for

CSESs (87%) and CWECs (90.9%). Decommissioning

plans provide specicaons on how the renewable

energy structure will be removed and the land restored

at the end of its useful life. Counes may have various

requirements for decommissioning and oen require

a surety bond or leer of credit from the renewable

energy company to ensure decommissioning costs are

covered. Economic Development Agreements (EDAs)

are oen required for both CSESs (n=15, 32.6%) and

CWECs (n=19, 43.2%). EDAs are an agreement between

the county and developer to various condions such

as the compleon of the project, payments to the

county, investments in infrastructure, and incenves.

Transportaon or road use agreement may be a part of

the EDA or required separately. Thirty-three counes

require this type of agreement for CSESs (71.7%), and

39 counes require it for CWECSs (88.6%). Figure 17

shows many other standard plans required, including

drainage or erosion control plans, emergency plans,

vegetaon plans, and (less commonly) property value

protecon plans.

Communicaon studies to look at potenal

interference, sound studies, environmental

assessments, and visual impact analyses are

commonly required for commercial renewable energy

projects (Figure 18). Glare analysis is required for

CSESs in some counes, and shadow icker analysis is

somemes required for CWECSs. Liability insurance,

with the county named as an insured, is required in

18 counes for CSESs (39.1%) and 32 counes for

CWECSs (72.7%). Cercates of design compliance are

another common requirement for both CSESs (n=15,

32.6%) and CWECSs (n=29, 65.9%). Addionally, 22

counes (50.0%) require cercaon by an engineer

for commercial wind towers.

22

Figure 18: Common plans required by zoning ordinances for CSESs and CWECSs

Figure 19: Common studies and assessments required by zoning ordinances for CSESs and CWECSs

Solar

Wind

Solar

Wind

Decomissioning Plan

Environmental

Assessment

Transportaon Plan

Visual Impact Analysis

Drainage/Erosion

Control Plan

EDA

Communicaons

Study

Vegetaon Plan

Shadow Flicker

Analysis

Maintenance Plan

Sound Study

Emergency Plan

Glare Analysis

Property Value

Protecon Plan

0

5

10

15

20

30

40

25

35

45

No. of Counes

No. of Counes

0

2

12

4

14

6

16

8

10

23

Ahani, S. & Dadashpoor, H. (2021). Land conict management measures in peri-urban areas: A meta-synthesis

review. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 64(11), 1909-1939.

Bednarikova, Z., Hillberry, R., Nguyen, N., Kumar, I., Inani, T., Gordon, M., & Wilcox, M. (2020). An examinaon

of the community level dynamics related to the introducon of wind energy in Indiana. hps://cdext.purdue.

edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Wind-Energy_Final-report.pdf

Beyea, W. Fierke-Gmazel, H., Gould, M. C., Mills, S., Neumann, B., & Reilly, M. (2021). Planning & Zoning for

Solar Energy Systems: A Guide for Michigan Local Governments. hps://www.canr.msu.edu/planning/uploads/

les/SES-Sample-Ordinance-nal-20211011-single.pdf.

Constan, M. and Beltron, P. (2006). Wind energy guide for county commissioners. U.S. Department of Energy

- Naonal Renewable Energy Laboratory, Wind Powering America. hps://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy07os/40403.

pdf

Ebner, P., Ogle, T., Hall, T., DeBoer, L., & Henderson, J. (2016). County Regulaon of Conned Feeding

Operaons in Indiana: An Overview. hps://ag.purdue.edu/extension/cfo/Reports/_Overview.pdf.

Hoen, B. D., Diendorfer, J. E., Rand, J. T., Kramer, L. A., Garrity, C. P., & Hunt, H. E. (2022). United States Wind

Turbine Database (v4.3). U.S. Geological Survey, American Clean Power Associaon, &Lawrence Berkeley

Naon Laboratory, hps://doi.org/10.5066/F7TX3DNO.

Indiana Code [IC] 36. Arcle 7. Chapter 4., Local Planning and Zoning. (2021). hp://iga.in.gov/legislave/

laws/2021/ic/tles/036#36-7-4. Accessed December 2021.

Indiana Oce of Energy Development. (2022). About OED. hps://www.in.gov/oed/about-oed/

Indiana Oce of Energy Development. (2022). Electricity. hps://www.in.gov/oed/about-oed/

Indiana Oce of Ulity Consumer Counselor. (2022). Voluntary Clean Energy Standards. hps://www.in.gov/

oucc/electric/key-cases-by-ulity/voluntary-clean-energy-standards/

Indiana Ulity Regulatory Commission. (2022). Research Policy & Planning Division. hps://www.in.gov/iurc/

Kumar, I. (2017). A Planning and Zoning Glossary. hps://cdext.purdue.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/ID-

228-W.pdf.

Marn, C. 2021. Community Planning for Agriculture and Natural Resources: A Guide for Local Government,

Renewable Energy Integraon for Sustainable Communies. hps://cdext.purdue.edu/guidebook

References

24

Marn, K. (2015). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Lifecycle of a Wind Energy Facility. hps://www.fws.gov/

midwest/endangered/permits/hcp/r3wind/pdf/DraHCPandEIS/MSHCPDraAppA_WindProjectLifecycle.pdf

Midconnent Independent System Operator, Inc. (2022). Generator interconnecon queue. hps://www.

misoenergy.org/planning/generator-interconnecon/GI_Queue/

Milbrandt, A.R., Heimiller, D.M., Perry, A. D., & Field, C.B. (2014). Renewable energy potenal on marginal

lands in the United States. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 29, 473-481.

Oce of Energy Eciency & Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy. (2021). Wind turbines: The bigger,

the beer. hps://www.energy.gov/eere/arcles/wind-turbines-bigger-beer

PJM. (2022). New services queue. hps://www.pjm.com/planning/services-requests/interconnecon-queues.

aspx

State Ulity Forecasng Group. (2021). Indiana Renewable Energy Resources Study. hps://www.purdue.edu/

discoverypark/sufg/docs/publicaons/2021%20Indiana%20Renewable%20Resources%20Report.pdf

Sward, J.A., Nilson, R.S., Katar, V. V., Stedman, R. C., Kay, D. L., I, J. E., & Zhang, K. M. (2021).

Integrang social consideraons in mulcriteria decision analysis for ulity-scale solar photovoltaic sing.

Applied Energy, 288, 116543.

Tegen, S., Keyser, D., Flores-Espino, F., & Hauser, R. (2014). Economic impacts from Indiana's rst 1,000

megawas of wind power. Naonal Renewable Energy Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy. hps://www.

nrel.gov/docs/fy14os/60914.pdf

U.S. Energy Informaon Administraon. (2021). Indiana state prole and energy esmates: Prole analysis.

hps://www.eia.gov/state/analysis.php?sid=IN

U.S. Energy Informaon Administraon. (2021). Electricity: Analysis & projecons. hps://www.eia.gov/

electricity/data/eia860/

25

These denions were adapted from a previous Purdue Extension report (Ebner, 2015).

: Separaon distance between two uses or a use and zoning district or municipality. Used as a tool to

reduce land use conict between uses oen considered incompable.

: A use dened within a local zoning ordinance that generally consists

of all necessary devices to convert solar energy into electricity. Commercial SESs may be dened as producing

energy delivered to a ulity's transmission lines or for o-site use. Their size may also delineate commercial

SESs in the zoning ordinance from small-scale or personal SESs.

: A use dened within a local zoning ordinance that

generally consists of all necessary devices to convert wind energy into electricity. Commercial WECs may be

dened as producing energy delivered to a ulity’s transmission lines or for o-site use. Their size may also

delineate commercial WECs in the zoning ordinance from small-scale or personal WECs.

Decommissioning Plan: Decommissioning plans provide specicaons on how the renewable energy structure

will be removed and the land restored at the end of its useful life. Counes may have various requirements for

decommissioning and oen require a surety bond or leer of credit from the renewable energy company to

ensure decommissioning costs are covered.

Development plan review: A process by which a plan commission, commiee, or sta reviews an applicant's

development plan to ensure the predetermined standards on the zoning ordinance have been met as allowed

by IC 36-7-4-1401.5.

: An agreement between the county and developer to various

condions such as the compleon of the project, payments to the county, investments in infrastructure, and

incenves.

Ordinance: A law, statute or regulaon enacted by a local government unit. For this study, ordinance will refer

to a jurisdicon’s zoning ordinance.

: A standard that requires that new uses, i.e. residences, follow the same buer as required of

a new renewable energy development to that buered use.

Screening: Provides a visual barrier between a use and adjoining properes. Shelterbelts, fencing, or earthen

mounds are some of the methods of use.

Setback: The distance from building/improvements from the property line or specied right of way.

26

: Also somemes referred to as condional use or special use. Generally understood to be a

use of property that is allowed under a zoning ordinance under special condions – something that needs to

be considered on a site-specic base- and must be approved by the board of zoning appeals.

Standards: Provisions of the zoning ordinance regulang the characteriscs of development of a parcular use

or zoning district.

Site plan: A scaled drawing that shows the placement of buildings and infrastructure of a development.

Zoning: Land use regulaons enacted by a local jurisidicon as a tool to implement their comprehensive plan.

(Kumar, 2017)

Zoning District: Designated districts based on the predominant use of land (e.g. residenal, commercial,

industrial, and agricultural). Each district has a set of uses that are permied by right or by special excepon

and a set of standards which determine he character of the district.

27

Purdue Extension, through the support of Hoosiers for Renewables, is conducng a comprehensive overview

study on land use regulaons for wind and solar energy and trends related to climate change planning. As

a primary contact for the county plan commission or local planning department, please help us understand

how Indiana communies make decisions about these complex issues and their associated impacts on local

planning and policies.

You will be asked to link to or upload content from wind and solar ordinances and zoning maps. You may also

need to reference Improvement Locaon Permits (ILPs) and Board of Zoning Appeals (BZA) records. It will be

helpful to have access to these documents during the survey as applicable.

Your parcipaon in this survey is voluntary. The survey should take approximately 15-20 minutes to complete

per plan commission. We recommend responding to this survey on a computer rather than a mobile device.

Please read each queson and page carefully before advancing. The back buon is not available throughout

the survey.

For informaon regarding the survey, please contact Tamara Ogle or Kara Salazar. This survey research is

referenced as IRB # 2021-685.

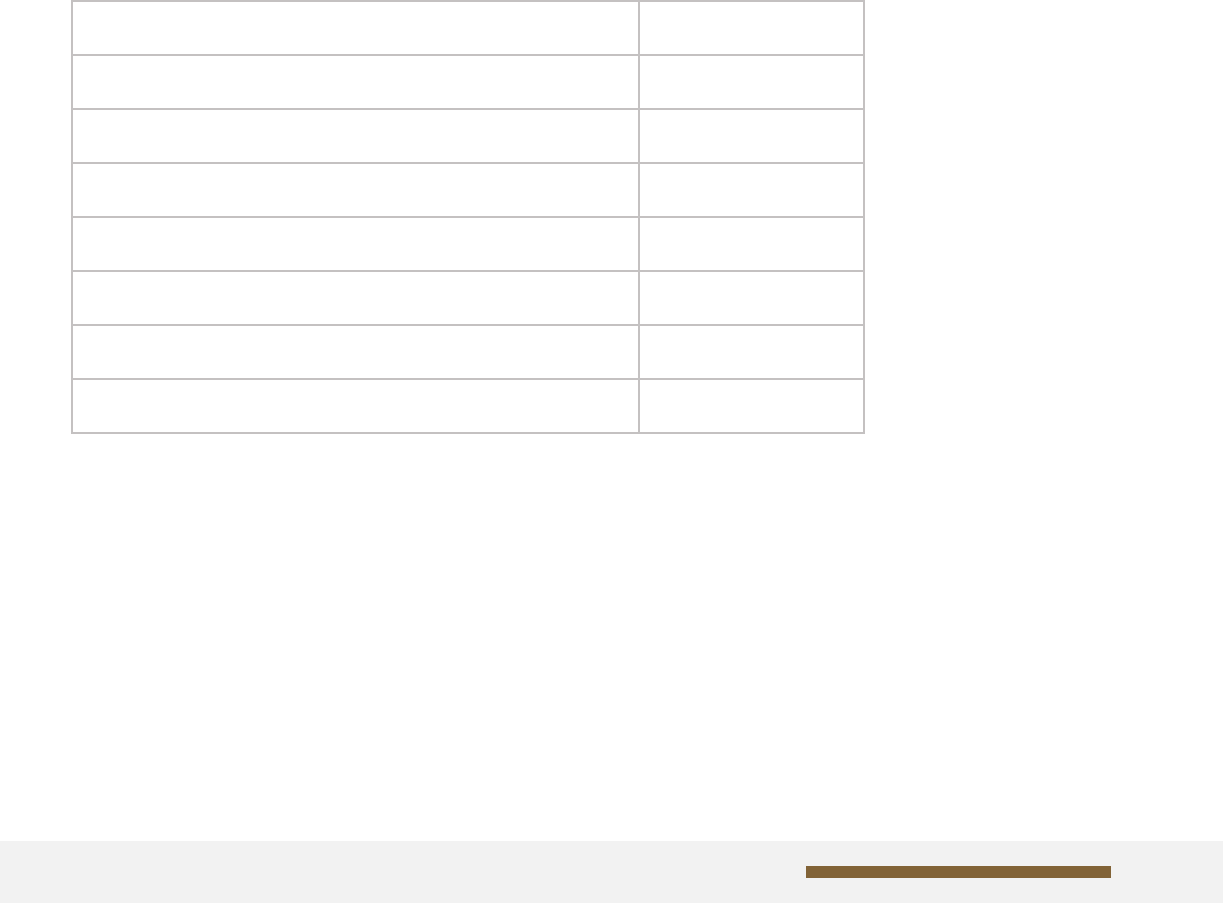

1. Please list the name of the plan commission(s) you serve. Leave any rows you don't need blank.

Survey Instrument Sent to County Plan Directors

Type of Plan Comission Type of Government

commission serves

Select one:

Area

Advisory

Metro

Select one:

Town

City County

Mul-Governmental

Select one:

Area

Advisory

Metro

Select one:

Town

City County

Mul-Governmental

Select one:

Area

Advisory

Metro

Select one:

Town

City County

Mul-Governmental

Renewable Energy and

Climate Change Community Planning Survey

28

Renewable Energy Ordinances

2. Does the county where you serve in a planning role have land use regulaons for renewable energy,

specically wind or solar?

3. Are there currently any proposed/pending ordinances or other regulaons for renewable energy

operaons?

4. When was the commercial solar or wind ordinance last updated?

Commercial Solar ______________________

Commercial Wind ______________________

5. Which of the following are included in the renewable energy ordinances?

Solar Wind

Small Scale Y/N Y/N

Commercial Y/N Y/N

Solar Wind

Small Scale Y/N Y/N

Commercial Y/N Y/N

Solar Wind

Buers Y/N Y/N

Design standards Y/N Y/N

Fencing requirements Y/N Y/N

Height restricons Y/N Y/N

Noise restricons Y/N Y/N

Setbacks Y/N Y/N

Screening Y/N Y/N

Vegitaon types Y/N Y/N

29

6. Do development agreements for renewable energy include the following:

7. Do you have a reciprocal buer for other development from renewable energy operaons?

8. In which zoning districts are commercial renewable energy systems considered a permied use or

special excepon. Is there land currently zoned for this district?

9. What ndings of fact do you consider in the special excepon (condional use) process?

__________________________________________________________________________

Solar Wind

Decommission plan Y/N Y/N

Economic development agreement Y/N Y/N

Maintenance plan Y/N Y/N

Road use and ditch maintenance agreement Y/N Y/N

Vegetaon plan Y/N Y/N

Other_______________ Y/N Y/N

Solar Y/N

Wind Y/N

District Name

Is there land available for

development zoned for

this district?

10. Have zoning districts in which commercial renewable energy systems are permited been restricted in

the last ve years?

10a. Please explain the restricon of zoning districts for perming commercial wind energy conversion

systems?________________________________________________________________

12. Has your community had any renewable energy developments proposed or built in the last ve years?

Y/N

12a. How many applicaons for Improvement Locaon Permits for commercial solar or wind in your in the

last ve years have required the following:

12b. How many commercial renewable energy projects have been approved and developed in your county

in the last ve years?

11. Please upload a copy of the ordinance, exisng moratoriums, rules or any other related documentaon

pertaining to guidelines for renewable energy or include a web link below.

___________________________________________________________________________

Solar Y/N

Wind Y/N

Solar and Wind Developments

Solar- Number of

ILPs granted

Solar-Number

denied

Wind-Number of

ILPs granted

Wind-# of

denied

Use Variance

Developmental

standards variance

Rezone

Special Excepon

Solar Wind

Number of permits

Acres

Energy Capacity in Megawas

31

13. Does your community have or have had a moratorium on commercial solar or in the last ve years?

13b. What was the me frame of the moratorium on commercial solar systems?

13c. What was the me frame of the moratorium on commercial wind systems?

14. To what extent have the following renewable energy regulaon acvies resulted in conicts in your

community within the last ve years? (Likert scale: 1=not at all; 2=very lile; 3=somewhat; 4=to a great

extent.)

14a. Indicate how the conict was resolved.

Solar Y/N

Wind Y/N

Renewable Energy Community Percepons

Solar Ordinances

Solar Development

Wind Ordinances

Wind Development

changes in your community?

Y/N/I don't know

Were there facilitated

forums or discussions to

come to an agreement?

Y/N/I don't know

Was there another

Solar Ordinances

Solar Development

Wind Ordinances

Wind Development

32

15. If changes were made in the last ve years to renewable energy regulaons/ordinances which (if any)

of the following factors inuenced those changes? (1=did not inuence at all; 10= greatly inuenced)

16. When was the comprehensive plan for your community last updated?__________________

17. Does the current comprehensive plan include goals or objecves related to climate change? Y/N

18. Indicate whether or not the current plan addresses the following topics to specically address climate

change. Also, indicate if the following topics will address climate change in the next plan update.

Aesthecs

Concerns about climate change

Concerns about energy availability

Concerns about scal impact to the county

Concerns from neighbors

Concerns about noise

Concerns about property values

Concerns about public health

Economic development opportunies

Loss of farmland

Proposal for a new or expansion of exisng development

Roune zoning ordinance update

Other _________________________

Climate Change Planning

Current plan Y/N Next Plan Y/N

Economic Development

Energy

Green infrastructure

Hazards management

Land use

Natural resources management

Public health

Public infrastructure

Social jusce

Transportaon

33

19. Indicate whether or not the current plan for your community includes the following adaptaon

strategies for addressing climate change. Also, indicate if the strategy will be addressed in the next plan

update. List up to three addional adapon strategies not listed.

20. Indicate whether or not the current plan includes the following migaon strategies for addressing

climate change. Also, indicate if the strategy will be addressed in the next plan update. List up to three

addional adapon strategies not listed.

Current plan Y/N Next Plan Y/N

Shiing development from ood prone areas

Installing green stormwater infrastructure pracces, such as

rain gardens, bioswales, etc.

Incorporang natural heat reducon strategies, such as

increasing tree canopy

Using built environment heat reducon strategies, such as

alternave building materials

Updang infrastructure for extreme weather events

Other________________________

Other________________________

Other________________________

Current plan Y/N Next Plan Y/N

Construcng mul-use trails and/or complete streets

Increasing mass transit opons

Incenvizing mass transit use

Installing roundabouts

Improving energy eciency in government opons

Creang policies that incenvize energy eciency in private

properes

Preserving green space

Increasing green space

Improving waste reducon in government operaons

Creang policies that incenvize waste reducon in private

properes

Other________________________

Other________________________

Other________________________

34

21. Please indicate to what extent the following statements occur in your community. (Likert scale:

Never(0%); Rarely(1-20%); Somemes (21-49%), Oen (50-99%); Always (100%)

22. Which of the following statements best reects the informaon available to you to help make decisions

when developing or amending renewable energy regulaons/ordinances?

Solar

o Reliable informaon is generally not available.

o Reliable informaon is available for some issues, but not for many of them.

o Reliable informaon is available for most issues.

Wind

o Reliable informaon is generally not available.

o Reliable informaon is available for some issues, but not for many of them.

o Reliable informaon is available for most issues.

The following survey secons were repeated for each plan commission the respondent entered in queson 1.

• Renewable Energy Ordinances

• Solar and Wind Development

• Renewable Energy Community Percepons

• Climate Change Community Planning

Decision makers in my community are well informed about climate change.

Decision makers in my community are a barrier to making progress on climate

change.

Community members are well informed about climate change.

Community members are a barrier to making progress on climate change.

In my community, strategies related to climate change are well funded.

In my community, strategies related to climate change are a polical priority.

Renewable Energy and Climate Informaon Resources

35

23. Which of the following sources of informaon do you use to help make decisions when developing or

amending renewable energy regulaons/ordinances? (Select all that apply)

25. Which of the following sources of informaon do you use to help make decisions about climate change

planning? (Select all that apply)

□ Cizen groups

□ Colleagues and peers

□ Consultants

□ Cooperave Extension

□ Environmental organizaons

□ Federal government agencies

□ Planning organizaons

□ Popular press

□ Social media

□ State government agencies

□ Universies

□ Other____________________________

□ Cizen groups

□ Colleagues and peers

□ Consultants

□ Cooperave Extension

□ Environmental organizaons

□ Federal government agencies

□ Planning organizaons

□ Popular press

□ Social media

□ State government agencies

□ Universies

□ Other____________________________

24. Please indicate whether you feel more reliable informaon is needed on the following issues to help

you make decisions when developing or amending renewable energy regulaons/ordinances. (Likert

scale 1=not needed; 10=greatly needed)

Conict management

Energy reliability

Fiscal impact to the county

Impact on aesthecs/view

Impact on environment

Impact on property values

Impact on public health

Concerns about public health

36

26. Please indicate whether you feel more reliable informaon is needed on the following issues to help

you make decisions about planning for climate change. (1 = not needed; 10 = greatly needed)

28. Which of the following units of government in the county employ professional planning sta

credenaled by the American Instute of Cered Planners (AICP)? (Y/N/I don't know)

29. Please ll out the following contact informaon.

30. Thank you for compleng this survey! Please use the space below for any comments or quesons

related to this survey. _______________________________________________________________

Climate change impacts

Climate change adapon strategies

Climate change migaon strategies

Communicang to the public about climate change

Communicang to local government ocials about

climate change

City

Town

County

Name

County

Phone Number

Email Address

Community Planning Informaon

27. Are you a cered planner credenaled by the American Instute of Cered Planners (AICP)?

o Yes

o No

o In the process of becoming cered

37

The following snapshots provide an overview of the land use regulaons of commercial solar and

wind developments in the unincorporated area of each county. This ordinance informaon is paired

with demographic informaon such as populaon, farmland percentage, and county type, which

may impact the likelihood or scale of renewable energy development. These snapshots reect use

standards specic to CSESs and CWECs. All development must sll comply with the district standards

of the zoning district where they are located. In 53 of the 82 counes with planning and zoning,

county planning oces reviewed their snapshot for accuracy. The ordinances used to create the

snapshots were collected from May-October 2021. Commercial renewable energy zoning standards

can be detailed. Contact the county planning oce for the most current and complete ordinance.

County Snapshots