SOUTHERN AFRICA

PHOTO CAPTION GOES HERE

REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT

COOPERATION STRATEGY

(RDCS)

OCTOBER 2020 – OCTOBER 2025

Approved for Public Release

by USAID

│

Southern Africa

Unclassified

i

ACRONYMS

AfrEA

African Evaluation Association

AFR

Africa Bureau

AOR

Agreement Officer Representatives

AIDS

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

AM

Activity Manager

ANC

Antenatal Care

ARISA

Advancing Rights in Southern Africa

ART

Antiretroviral Therapy

ASP

Alternative Service Provider

AU

African Union

BAU

Business as Usual

BHA

Office the Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance

C-TIP

Counter-Trafficking in Persons

CCMDD

Central Chronic Medication Dispensing and Distribution

CCNPSC

Cooperating Country National

CDC

Centre for Disease Control

CGPU

Child and Gender Protection Unit

CLA

Collaborating, Learning and Adapting

CLEAR

Centers for Learning on Evaluation and Results

COMESA

Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa

COP

Country Operational Plan

COR

Contracting Officer Representatives

COVID-19

Corona Virus Disease 2019

CSI

Corporate Social Investment

CSR

Corporate Social Responsibility

CWC

Combating Wildlife Crime

DBE

Department of Basic Education

DBSA

Development Bank of Southern Africa

DCHA

Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance

DDI

Bureau for Development, Democracy, and Innovation

DFID

Department for International Development

DHS+

Democratic Health Survey Plus

DIB

Development Impact Bond

DMD

Deputy Mission Director

RDO

Regional Development Objective

ii

DOJ

Department of Justice

DREAMS

Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored, and Safe

DRG

Democracy and Governance

DSD

Department of Social Development

ECD

Early childhood development

EU

European Union

FSR

Financing Self-Reliance

G2G

Government to Government

GBV

Gender-based Violence

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

GHG

Greenhouse Gases

GH-PSM

Global Health Procurement Supply and Management

GHSC-PSM

Global Health Supply Chain for Procurement and Supply Management

GIS

Geographic Information System

GIZ

German Society for International Cooperation

GoA

GoB

GoE

GoL

Government of Angola

Government of Botswana

Government of Eswatini

Government of Lesotho

GoN

Government of Namibia

GoSA

Government of South Africa

HFA

Health for All

HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

IAA

Interagency Agreement

ICASS

International Cooperative Administrative Support Services

ICS

Integrated Country Strategy

ICT

Information and Telecommunications Technology

IDIQ

Indefinite Delivery Indefinite Quantity

IIAG

Ibrahim Index of African Governance

ILO

International Labor Organization

ILOSTAT

International Labor Organization Department of Statistics

IP

Implementing Partner

IPPs

Independent Power Producers

IR

Intermediate Result

ITCZ

Intertropical Convergence Zone

J2SR

Journey to Self-Reliance

KAZA

Kavango-Zambezi

LPC

Limited Presence Country

iii

M&E

Monitoring and Evaluation

M2M

Mothers2Mothers

M-DIVE

Malaria Data Integration and Visualization

MELs

Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Plans

MEO

Mission Environmental Officer

MJHR

Ministry of Justice and Human Rights (Angola)

MOH

Ministry of Health

NAPA

National Adaptation Plan of Action

NCCAS

National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy

NCCRP

National Climate Change Response Policy

NDCS

National Determined Contributions

NDOH

National Department of Health

NDP

National Development Plan

NHI

National Health Insurance

NICTIP

National Intersectoral Committee on Trafficking in Persons

NMCP

National Malaria Control Program

NPA

National Prosecuting Authority

NPC

Non-Presence Country

NPI

New Partnership Initiative

NSP

O2P

National Strategic Plan

Operational Optimization Platform

NUP

New and Underutilized Partners

OAA

Office of Acquisition and Assistance

ODA

Official Development Assistance

OE

Operational Expense

OOF

Other Official Flows

OU

Operating Unit

PACOTIP

Prevention and Combating of Trafficking in Persons

PAD

Project Appraisal Document

PEPFAR

President’s Emergency Plans for AIDS Relief

PFM

Public Finance Management

PLHIV

People living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus

PMI

President’s Malaria Initiative

PMTCT

Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission

PPR

Performance Plan and Report

PSE

Private Sector Engagement

PSC

Personal Services Contractor

iv

PTA

Parent Teacher Associations

RDCS

Regional Development Cooperation Strategy

RDO

Regional Development Objective

REED

Regional Environment, Education and Democracy

REGO

Regional Office

REXO

Regional Executive Office

RF

Results Framework

RFMO

Regional Financial Management Office

RHAP

Regional HIV/AIDS Program

RHO

Regional Health Office

RIDMP

Regional Infrastructural Development Masterplan

RIG

Regional Inspector General

RISDP

Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan

RISE ll

Reducing Infections through Support and Education

RLO

Resident Legal Officer

ROAA

Regional Office of Acquisition and Assistance

ROL

Rule of Law

RPPDO

Regional Program and Project Development Office

RDR

Refining the Relationship

SACU

Southern African Customs Union

SADC

Southern African Development Community

SAMEA

South African Monitoring and Evaluation Association

SAPS

South African Police Service

SBCC

Social Behavior Change and Communication

SBU

Separate but Unclassified

SDG

Sustainable Development Goal

SIB

Social Impact Bond

SIPO

Strategic Indicative Plan of the Organ

S/GAC

State Department’s Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator

SODVA

Sexual Offences and Domestic Violence Act

SRLA

Self-Reliance Learning Agenda

STI

Sexually Transmitted Infections

TB

Tuberculosis

TCN

Third Country National

TIP

Trafficking in People

TTL

Technical Team Lead

TVET

Technical and Vocational Education and Training

v

UN

United Nations

UNFCCC

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

URTC

Ubunye Regional Training Center

U.S.

United States

USAID

United States Agency for International Development

USAID/SA

United States Agency for International Development/Southern Africa

USDH

United Stated Direct Hire

WASH

Water Sanitation and Hygiene

WHO

World Health Organization

YOLO

You Only Live Once

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acronyms i

Table of Contents 6

Executive Summary 1

USAID/SA Results Framework 4

Regional Context 4

Strategic Approach 7

Results Framework Narrative 10

RDO 1: Inclusive Economic Growth Catalyzed 11

RDO 2: Governance Strengthened 19

RDO 3: Resilience of People and Systems Strengthened 23

Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning 31

Annex A: Regional Operations Map 33

Annex B: PEPFAR 35

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

United States Agency for International Development/Southern Africa’s (USAID/SA) strategic goal over

the next five years (October 2020- September 2025) is to advance the region toward becoming more

integrated, prosperous, and ultimately self-reliant. This goal can only be achieved when the needs of

both women and men in the region are addressed. The Regional Development Cooperation Strategy

(RDCS) is unlike previous USAID/SA strategies and integrates what was traditionally South Africa’s

Country Development Cooperation Strategy. The strategy also exclusively focuses on driving self-

reliance through strategically allocating its resources and partnering with three main stakeholders: the

private sector, governments, and citizens to catalyze inclusive economic growth, strengthen governance,

and advance the resilience of people and systems. Through this regional and partnership-based

approach in programming, USAID/SA will contribute to the Journey to Self-Reliance (J2SR) of the

individual countries that make up the region.

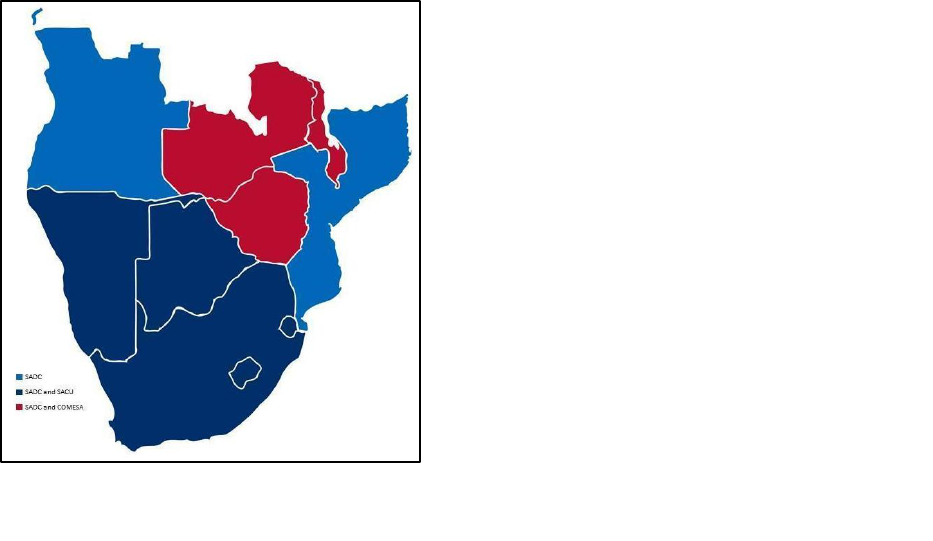

Southern African Countries

The USAID/SA strategy covers eleven countries in the

Southern African region of Angola, Botswana,

Eswatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique,

Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The

regional landscape is complex with countries often

belonging to more than one economic community or

organization. All the countries in the region are

members of the Southern African Development

Community (SADC). Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho,

Namibia and South Africa are also members of the

Southern African Customs Union (SACU), while

Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe are also members of

the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa

(COMESA). This adds to the complexity of fostering

inclusive economic growth and addressing the

remaining development challenges in Southern Africa.

It also provides an opportunity to align USAID/SA’s

projects and activities to the development priorities of the host country governments and the regional

economic communities and/or organizations to which the different countries belong.

Countries in the region share high levels of unemployment, poverty, and inequality. There are also

extraordinary differences in terms of economic size, population, resource potential, economic

infrastructure, human capital, political environment, and official languages. The main regional

challenges to sustainable regional economic integration and dynamic growth include fiscal challenges,

high levels of government debt, poverty, unemployment, gender and income inequality, poor education

quality, over-dependence on commodities, and a lack of private sector participation and investment.

There is also a lack of economic diversification as most countries rely on commodities (copper, oil,

diamonds, gold) for industrial production, exposing them to commodity price shocks.

Significant development challenges remain to address the triple challenges of unemployment, poverty,

and income inequality in the region. These challenges have a gendered dimension that cannot be

ignored. An analysis of the socio-cultural and economic situation of the region shows that gender

inequalities persist in every sector. Generally, women and girls face challenges in accessing legal rights,

education, health and economic resources, amongst others. Despite efforts that have been made by

2

countries in the region to improve their situation, there are several specific technical, socio-cultural and

economic constraints that account for this situation. These include, but are not limited to: increased

incidences of gender-based violence (GBV) at all levels; disparities in educational attainments and in

formal wage employment between women and men; and disparities in access, benefit, opportunities

and control over resources such as land, housing, water, credit, technology, extension services and other

productive sectors such as mining.

Youth share a disproportionately large percentage of unemployment in the region, and if not addressed

could lead to an increase in protests, civil unrest and political instability. The large percentage of youth

in Southern Africa could also be a dividend, if catalyzed to productively contribute to economic growth.

Table1: Regional unemployment, poverty and income inequality.

Country

Unemployment Rate

1

Poverty Rate

2

Income Inequality

Coefficient

3

Angola

6.9%

47.6%

51.3

Botswana

18.2%

16.1%

53.3

Eswatini

22.1%

42%

54.6

Lesotho

23.4%

61.3%

44.9

Madagascar

1.8%

77.6%

42.6

Malawi

5.7%

71.7%

44.7

Mozambique

3.2%

62.9%

54

Namibia

20.3%

13.4%

59.1

South Africa

28.2%

18.9%

63 (highest in the world)

Zambia

11.4%

57.5%

57.1

Zimbabwe

5%

21.4%

44.3

1

International Labour Organization (ILO), ILOSTAT database. Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modelled ILO estimate) - Sub-

Saharan Africa.

2

World Bank, Development Research Group. Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)) (% of population).

3

World Bank, Development Research Group. Gini index (World Bank estimate) - Sub-Saharan Africa.

3

The regional landscape analysis which is based on an aggregation of the individual J2SR Country

Roadmaps in the region, further underlines some of the specific challenges that compound regional

unemployment, poverty and inequality.

It is clear from the regional landscape analysis that there is a need to strengthen civil society across the

region to drive transparency and government accountability, combined with building capacity to

coherently implement policies. Education quality across the region is very poor and needs to be

addressed as a long-term driver of economic growth and innovation. Government and tax system

effectiveness remains a challenge to growth and development, as well as the capacity of the regional

economies to grow inclusively and at the rates required for development.

South Africa is the nexus for most of the region's trade, manufacturing, finance, and education. There is

a high degree of market concentration in South Africa and regional economies are deeply and critically

linked to South Africa. As an upper middle-income country, South Africa still faces significant challenges,

but is also the most developed country in the region. Leveraging South Africa’s advanced level of

development as a catalyst for regional growth and development remains fundamental.

While countries in the region typically have a strong respect for religious freedoms, USAID/SA will

coordinate with the relevant U.S. Embassies on the Executive Order on Advancing International

Religious Freedom. USAID/SA already has a diverse partner landscape including many faith-based

organizations and consistent with the New Partnership Initiative will continue to pursue avenues for

engaging more local organizations.

Regional challenges need to be addressed through a regional approach and programming that drive

inclusive economic growth. In order to achieve the goal of an integrated, prosperous, and ultimately

self-reliant region the strategy focuses on catalyzing inclusive economic growth, strengthening

governance and advancing the resilience of people and systems in the region, and to leverage South

Africa’s strategic advantage to compound development gains. The RDCS allows USAID/SA to address

last-mile challenges in South Africa as a transition country, whilst simultaneously tackling regional issues

that strengthen inclusive growth.

4

USAID/SA Results Framework

REGIONAL CONTEXT

While substantial progress has been made regarding certain aspects of the J2SR, the Southern Africa

region continues to experience serious challenges. Taken together, South Africa (66 percent) and

Angola (14 percent) represent 80 percent of the region’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which

highlights the dramatic differences between countries. In purely economic terms, low private sector

growth is made worse by the lack of diversified economies, labor market challenges, and high

unemployment resulting in sluggish regional economic growth. The economic impacts from the 2020

Coronavirus disease–2019 (COVID-19) pandemic will reduce growth in Southern Africa by an estimated -

6.2 GDP reduction in 2020 with an estimated 2.9 percent growth recovery in 2021. The COVID-19

related economic impacts will likely erase the economic and income gains of the past ten years.

Experience from previous epidemics suggest that COVID-19 will impact groups who are most vulnerable

and amplify any existing inequalities across countries, communities, households and individuals.

Economic growth has been slow and is a combination of low commodity prices from drops in demand

from the retail and industrial sectors, poor business enabling environments, depressed retail,

devastated tourism and associated natural resource conservation efforts, fractured global supply chains,

low or ineffective public spending for investment or education, high levels of corruption, and poor

regional integration. As governments face significant drops in revenue and large increases in spending

on health care and social assistance, debt sustainability and sovereign debt crises loom within the next

five years. All challenges will limit the region’s ability to finance its own self-reliance.

The social development sector similarly faces challenges as the region continues to be the epicenter of

the global Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) epidemic

with an estimated 14.9 million people who are HIV positive. High levels of cross-border migration also

require a region wide approach to health in Southern Africa, particularly when combatting transmittable

diseases such as HIV and TB. Gender inequality is still a strong driver of the HIV/AIDS epidemic: 59

5

percent of new infections in Southern Africa are women, but 53 percent of AIDS related deaths are men.

Young women 15 to 24 years old are only 10 percent of the total population, but 26 percent of new HIV

infections. The PEPFAR programs in the region have increasingly focused on adolescents girls as the rate

of infection is generally three times higher than that of adolescent boys. Without a healthy workforce,

long-lasting economic growth can not be sustained. Reproductive health and access to family planning

also reveal wide gaps in the region. The SADC Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR)

Strategy highlights that 24 percent of all pregnancies in Southern Africa end in abortion. Unsafe

abortions contribute an estimated 10 to 13 percent of maternal mortality. There are only two SADC

countries in which abortion is available on demand in the first trimester (South Africa and Mozambique).

Abortion is available under certain circumstances in all SADC countries, with varying degrees of

restriction. Maternal mortality across most of SADC is unacceptably high and declining too slowly to

meet the SDG target.

At least one in three women in the region have experienced GBV in their lifetime. Emotional abuse, the

most prevalent form of GBV, is the type of GBV least likely to be reported to the police. Sexual and

physical abuse are grossly under-reported. Over the past decade considerable progress has been made

in passing progressive laws to address GBV. Of the 15 SADC countries, 13 have sexual assault legislation

and 12 on domestic violence. All SADC countries now have National Action Plans to End GBV.

Trafficking in Persons (TIP) is a crime of global magnitude and affects the Southern Africa region in a

multitude of ways. SADC citizens face a myriad of vulnerabilities that make them susceptible to

trafficking, such as endemic poverty, minimal access to health and education, gender inequality,

unemployment and a general lack of opportunities. South Africa is a primary destination for trafficked

persons in the Southern Africa region and within Africa at large. It is also an origin and transit country

for trafficking towards Europe and North America. It is important to note that there is a dearth of

information on the crime in the region which in turn hampers a regional response to the crime. Within

the SADC region, all substantive Member States are parties to the United Nations Convention against

Transnational Organised Crime (UNCTOC) and the TIP Protocol and while some countries have enacted

legislation addressing TIP, implementation is irregular and uncoordinated.

The region has also been particularly hard hit by recurrent climate-induced hazards that include

droughts, floods, and the spread of deadly communicable disease. The threat of these hazards is

exacerbated by poorly planned land use, misuse of essential natural resources including inefficient

water usage and contamination, prolific waste and energy mismanagement, and persistent wildlife

crime and trafficking. Women and girls constitute the majority of those impacted by the effects of

climate change and environmental degradation, yet they remain less likely to have access to

environmental resources. The region’s vast stock of natural resources represents an important revenue

generation stream. Protection of this stock is vital to ensuring that the region’s people are healthy and

safe from disease, and for the region’s most important export industries: agriculture and mining. These

resources are also essential to the success of the domestic tourism and services industries, which

together employ millions of people across the region.

4

Across the region, middle-income countries all score well for commitment and capacity. However, the

low and middle-income countries score relatively poorly for education quality. Apart from Botswana, all

have relatively high poverty rates. Poverty is especially high in Malawi, Madagascar, and Mozambique.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the region struggled with high official unemployment rates ranging

from ten to 30 percent of the labor force and these rates are much higher for the youth. The business

environment affects commitment in Angola, Madagascar, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe, while the

4

USAID/Southern Africa Tropical Forestry and Biodiversity Assessment, August 2017.

6

capacity of the economy (GDP per capita, Information and Telecommunications Technology (ICT), and

export sophistication) is limited in Angola, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia, Madagascar, Malawi,

Mozambique, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Several countries in the region rely on relatively narrow extractive export sectors. These include

petroleum and gas (Angola, Mozambique), copper and cobalt (Zambia, Namibia), gold, diamonds, and

platinum (Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa, Zimbabwe), textiles (Lesotho), and agricultural exports

(Eswatini, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe). All countries in the region rank in the

bottom half of the world for export sophistication and complexity. For example, Angola ranks 131 of

133 countries for export complexity due to its strong reliance on oil exports. Furthermore, only Namibia

and Zambia have been able to increase their export complexity according to their J2SR roadmaps. If the

region remains reliant on a narrow band of industries, especially commodities, this may amplify

economic shocks on the domestic markets and impair economic resilience. The region primarily exports

commodities and raw goods to China, India, and Europe for processing, and then imports finished goods

back.

Based on Country Economic Reviews in Madagascar, Mozambique, South Africa and Zambia, common

binding constraints are weak competitiveness from poor business-enabling environments and high

barriers to entry.

Southern Africa remains a highly inequitable place economically, with large gaps both between

countries and within them in terms of income. These inequalities exacerbate gender disparities through

the imposition of resource constraints, reinforcement of gendered stereotypes and discrimination in

employment, and imposition of barriers to equitable labor force participation. Three issues which affect

women disproportionately in the region are barriers to informal cross-border trading, barriers for

female entrepreneurs, and constraints in the agriculture sector, both at the subsistence and commercial

level.

Outside of the formal labor market, many women engage in entrepreneurial activity, either as their

main source or a supplementary form of income. Female entrepreneurs face many additional barriers

due to gender norms, however; access to credit, financial literacy, and formal property ownership are

some of the most cited issues. In SADC, 77 percent of the population rely on the agriculture sector for

income and employment, most of them women. Land rights and ownership titles are guaranteed by

statutory law in most countries, but women are often barred from owning their land by customary laws

or inheritance practices. Without recognition of their land ownership, many female farmers cannot

secure credit or extension services such as improved seedstock or fertilizer.

Another widespread and often gendered issue for the Southern Africa region is youth unemployment.

Pre-COVID-19, the World Bank estimated that 50 percent of youth in sub-Saharan African will be

unemployed or economically inactive by 2025. South Africa's youth unemployment rate exceeds 55

percent and in Zimbabwe it is as high as 80-90 percent. Youth disengagement contributes to potential

political instability in the region. With conditions such as low economic growth, high poverty, low

government transparency and accountability, high inequality, and low economic diversification and

resilience, engaging youth needs to remain a high priority.

As a result of low growth and inconsistent government fiscal policies, several countries in the region face

fiscal distress, namely: Angola, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Zambia. Now, due to the

drop in commodity prices and the economic repercussions of the pandemic, the rest of the region is

facing fiscal crises including South Africa whose debt to GDP ratio is forecast to increase to 85 percent by

the end of 2020. With drops in foreign and domestic investment, reduced revenue collection, and rising

7

unemployment, fiscal pressures may increase in the near term. As such, service delivery, including for

health care, education, and poverty alleviation, may face additional constraints.

Multilateral and bilateral development agencies and financial institutions have projects and offices

based in South Africa. Most donors work as strategic partners with the government of South Africa

(GoSA) to provide technical assistance and capacity building. The African Development Bank funds

technical assistance and capacity building activities in core skills required for effective implementation

of the Public Finance Management (PFM) legislation and procedures through the Development Bank of

Southern Africa (DBSA). The European Union (EU) supports peace, security and regional stability,

regional economic integration (including SADC and COMESA support), regional natural resource

management with a focus on the SADC Regional Agriculture Policy, institutional capacity building

(including public financial management). The German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) works

on environment and climate change, economic development and employment, and democracy and

governance (with some USAID support). The United Kingdom's Department for International

Development (DFID) ended bilateral assistance in 2015, but through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

maintains a regional office in South Africa and supports partnership programs which work with South

African institutions to strengthen their development role in Africa, in areas including tax capacity

building, tackling climate change, and service delivery monitoring. Regional development projects

including trade and environment leverage South Africa's predominant role in the region and regional

organizations such as SADC. These priorities align well with USAID's, and while there is some technical

cooperation, there are more opportunities to leverage.

SADC is arguably the most important regional organization in Southern Africa and is recognized by the

African Union (AU) as a regional economic community. The main objectives of SADC are to achieve

development, peace and security, and economic growth, to alleviate poverty, enhance the standard and

quality of life of the peoples of Southern Africa, and support the socially disadvantaged through regional

integration built on democratic principles and equitable and sustainable development. The aspirations

of Southern Africa are clearly spelled out in the Declaration and Treaty that established the shared

community of SADC. These aspirations are a united, prosperous, and integrated region.

SADC has a long history of collaborating with bilateral and multilateral donors to facilitate the

mobilization of resources for the attainment of SADC’s regional integration and poverty reduction

priorities. These partnerships assist SADC to deliver specifically on the implementation of the region’s

two key strategies: The Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RISDP) and the Strategic

Indicative Plan of the Organ (SIPO). SADC remains a key regional organization that aligns with the goals

and regional development objectives of the RDCS, and USAID/SA will continue to engage and work with

SADC on all regional projects where there is alignment between the goals and objectives of both

organizations.

STRATEGIC APPROACH

The purpose of foreign assistance is to end the need for it to exist, and USAID/SA’s innovative strategic

approach of a combined country and regional strategy with three integrated Regional Development

Objectives (RDOs) is structured to contribute to exactly this. The approach aligns and reinforces USAID’s

Policy Framework, the J2SR, the United States’ National Security Strategy, and the Department of State

and USAID’s Joint Strategic Plan by countering instability that threatens U.S. interests, and by laying the

foundation for, and accelerating, sustainable development, which opens new markets and supports U.S.

prosperity and security.

8

Strategic Choices: Under the new strategy, USAID/SA is making several strategic choices. The first is to

have an integrated regional and country strategy, with integrated RDOs that are all necessary to drive

regional growth and integration as a catalyst for self-reliance. This decision will ensure that USAID/SA

can make strategic programming choices based on resources and the various countries' level of self-

reliance. The second is to focus on partnering with three main stakeholders, specifically the private

sector, governments, and citizens, to increase commitment and capacity in each of the partner countries

in the region. The third is to leverage South Africa’s strategic advantage across each of the sectors in

which USAID works, to help achieve a strategic transition within South Africa over the lifetime of the

strategy. As the Mission realigns its efforts over the course of the next five years, significant changes

must be made. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for strong local partners who can

mobilize to face emerging challenges and the need to consider the gendered impacts that have emerged

in this health emergency.

Chosen Priorities: The numerous development challenges still facing the region, as well as the realities

of the COVID-19 pandemic, have intensified the need to address existing vulnerabilities such as access to

quality health care, basic education, and employment, particularly for women and youth as highlighted

in the J2SR Landscape Analysis. The devastating effects of poverty, discrimination and lack of

opportunity affect women in multiple ways, not just their income levels. Women have fewer economic

rights, and lower access to economic opportunities and resources, including land and credit facilities.

They are vastly under-represented in many occupations, especially in professions such as science and

technology. Women, whether formally employed or not, also shoulder the burden of unpaid activities

such as caring for family members. Economically strengthening women, who account for more than half

of the population in the region, is not only a means to spur economic growth, but it is also a matter of

advancing human rights. Strengthening democratic governance and accountability is critical across the

region to solidify democratic gains and combat corruption. In many sectors, statutory laws are ignored

or not enforced, either due to prevailing social beliefs or a lack of resources and those most affected are

women and vulnerable populations. As the 2017 USAID/SA Tropical Forestry and Biodiversity

Assessment points out, factors such as climate change, weak governance, and resource overexploitation

have underscored the nexus of natural resource management, health, sustainable land use, and

economic development and the importance of integrated systems approaches to address the dynamic

relationships between these sectors and the need for resilient support networks.

Strategic Alignment: The USAID/SA RDCS aligns with Goals 2 and 3 of the State-USAID Joint Strategic

Plan (i.e. “Renew America’s Competitive Advantage for Sustained Economic Growth and Job Creation"

and “Promote American Leadership through Balanced Engagement”). It also aligns with Executive Order

13677 on Climate Resilient International Development which requires the integration of climate-resilient

considerations into all of USAID’s work.

Leveraging the Catalytic Role of South Africa: South Africa is the only country in the region designated

by USAID/Washington for strategic transition. With advanced levels of commitment and capacity to

plan, manage, and resource its own development, there are numerous opportunities for South Africa to

leverage its strategic advantage to assist countries in the region with achieving greater regional growth

and integration. USAID’s J2SR Policy Framework rightly requires that the relationship between the U.S.

and designated strategic transition countries must mature over time, from a donor-recipient dynamic to

one of enduring economic, diplomatic, and security partnership. South Africa’s importance in the region

can not be understated, it is a driver of regional economic growth and stability, the most significant

trading partner in Southern Africa, and the largest trading partner of the U.S. in Africa. Applying the

results framework to South Africa as a strategic transition country will enable USAID/SA to further

expand access to finance, mobilize South African private capital for local and regional development,

9

deepen regional and international trade relationships, and leverage South Africa’s technology and

human capital to drive innovation and growth. This approach will require a different model of

partnership with the GoSA, the private sector, and other stakeholders, as well as the use of innovative

and nimble implementing mechanisms and leveraging of USAID’s convening power. It is critically

important to acknowledge, however, that South Africa faces serious impediments itself to economic

growth and is faced with the triple challenge of high levels of unemployment, poverty, and inequality of

which women are disproportionately affected. Conditions of unemployment, poverty and inequality are

fertile breeding ground for violence, in particular violence against women. A multi-pronged approach is

arguably required to address violence against women such that South Africa remains on track as a

strategic transition country. The integrated RDOs and IRs provide for these issues to be addressed in an

integrated manner, involving economic, social, infrastructural, legal and attitudinal interventions, as

well as the mainstreaming of gender considerations in both public and private sector programs in order

to leverage development gains and decrease the risk of economic backsliding.

Use of Resources to Build Financial Self-Reliance: Financial Self-Reliance (FSR) is a cornerstone of the

J2SR. It is critical to adopt a holistic approach to assessing the range of interrelated and interconnected

elements that contribute to a country’s ability to transparently and inclusively resource its own

development. USAID/SA’s will work across sectors to move away from traditional Domestic Resource

Mobilization (DRM) approaches that have centered on public revenues, to one that targets and

advances the spectrum of public and private resources. USAID/SA will strategically build the capacity of

countries in the region, across development sectors, to mobilize, plan and invest resources that drive

sustainable development. Increasing trade and investment, will drive economic growth and increase

financial resources available for development.

Engaging the Private Sector: Private Sector Engagement (PSE) is a means to an end. USAID/SA will

engage and partner with the private sector in all areas to improve development results. PSE is not a

development objective or IR: it is the means through which we achieve those results. The private sector

is central to the successful execution of the RDCS, not only as the main driver of economic growth and

employment in the region, but also as a partner in development. USAID/SA will significantly increase its

engagement with the private sector across all sectors and ensure that there is strategic alignment

between USAID development objectives and the objectives of the private sector. This will lead to

development programs that are co-created by the private sector, and as a result are more scalable and

sustainable as resources are shared and leveraged.

Regional Partnerships: Southern African host country governments and intergovernmental

organizations have always been and will continue to be key development partners. USAID/SA engages

with host country governments, intergovernmental organizations and other development actors across

all development sectors and at various levels to ensure that there is strategic alignment and buy-in. This

enables USAID/SA to define and redefine the USG’s relationship within the region.

South Africa, as a strategic transition country, forms a core pillar and an enabler across the RDOs.

Leveraging South Africa’s private financial resources, advanced and sophisticated financial systems and

infrastructure, and vibrant private sector is critical to achieving regional development results. At the

same time, it allows USAID/SA to evolve its relationship with South Africa from a traditional donor-

recipient to one supporting long-term economic, diplomatic, and security partnership. This will require

USAID/SA to play a convening and connecting role within South Africa to mobilize U.S. Government

agencies, the private sector, and government to bolster trade and investment, and expand the private

sector. The impact of leveraging South Africa’s financial resources and expertise will be mutually

beneficial.

10

G2G funding is already happening in South Africa in the health sector, where USAID/SA has been very

active for a number of years. To expand on these successes and to begin “transitioning” USAID’s

relationship into other sectors, USAID/SA and the GoSA have signed two G2G agreements. These

agreements are with the Department of Basic Education (DBE) and the Department of Social

Development (DSD). The purpose of the activity with DBE is to provide support to the national DBE to

align and consolidate the Life Orientation Conditional Grant to better support the implementation

mandates of the National Policy on HIV, Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and TB. The purpose of

the activity with DSD is to strengthen DSD’s capacity to scale-up the implementation of primary

prevention of sexual violence and HIV activities among 10 to18 year-olds, link them to the 95-95-95

5

clinical cascade and reduce incidence of HIV and AIDS through social behavior change and

communication programs (SBCC). Furthermore, USAID/SA will continue direct funding for G2G and to

local indigenous partners, which currently make up most of the health funding. By partnering directly

on G2G and with local institutions and building their capacity to implement locally-led solutions,

USAID/SA will maximize the potential impact of USAID resources by shifting accountability and

ownership to local stakeholders.

South Africa has several areas of strategic advantage as it relates to the areas of civil society and media

and child health. USAID/SA will continue to develop South Africa’s civil society organizations, including

in the media space, in order to serve as a potential resource on how to combat closing space, bring

attention to corruption, and strengthen the voice of people and communities whose livelihoods are

potentially threatened due to poor access to and quality of services provided.

Other U.S. Government Actors: USAID/Southern Africa works in close coordination with its interagency

partners in the region to align its strategic approach with ongoing programming. In particular, the

Mission coordinates on a daily basis with the U.S. Department of State on the President’s Emergency

Plans for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) across the region, as well as with the U.S. Center for Disease Control

(CDC) on health programming (e.g. TB, malaria, HIV/AIDS, COVID-19, etc.). The Mission also liaises

regularly with the U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Trade Representative’s

Office, U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Foreign Agricultural Service, U.S. Small Business

Administration, U.S. Trade Development Agency, U.S. International Development Finance Corporation,

and the Export Import Bank often through the Shared Prosperity Working Group chaired by the Political-

Economic Section of U.S. Embassy/Pretoria.

Donor Coordination: At the technical level, USAID coordinates with other donors through forums and

working groups in coordination with SADC. Throughout the region, USAID participates actively in

country-level donor working groups in environment, energy, health, democracy and governance, and

education, among others. To address climate risks affecting USAID programming, USAID/SA will

coordinate with donors to join resources to build resilience in the programs supported.

RESULTS FRAMEWORK NARRATIVE

RDCS Goal and Narrative: Under the new integrated strategy, USAID/SA’s five-year (2020-2025)

strategic goal is to help the region advance toward becoming more integrated, prosperous, and self-

reliant. USAID will achieve this by partnering with three main stakeholders: the private sector,

governments, and citizens to catalyze inclusive economic growth, strengthen governance, and advance

the resilience of people and systems.

5

95-95-95 for treatment is defined as 95% of people living with HIV know their HIV status; 95% of people who know their status on

treatment; and 95% of people on treatment with suppressed viral loads.

11

The purpose of foreign assistance is to end the need for it to exist, and USAID/SA’s innovative strategic

approach of a combined country and regional strategy with three integrated RDOs is structured to

achieve exactly this. The strategic approach necessitates partnering with the private sector, local

governments, and civil society and redefining relationships based on complex and varied regional

characteristics. The three RDOs work in an integrated fashion and will enable USAID/SA to harmonize

investments in sustainable growth, inclusion, and democracy which will ultimately enhance capacity and

increase commitment of the countries in the region.

Cross-sectoral integration is fundamental. The Policy Framework states: “Technical specialties and

program areas allow useful divisions of labor within USAID, but they do not reflect the real world. It is

impossible, for example, to separate children’s education from their health and nutrition, their parents’

livelihoods, norms around the equality of girls’ and boys’ schooling, or the government’s administrative

effectiveness.” For economic competitiveness and sustainable regional economic integration to grow,

the enabling environment and access to quality infrastructure must be improved, trade and investment

increased, and the private sector mobilized for inclusive development. In particular, the under-

utilization of the private sector to drive growth remains a huge opportunity; under the new strategy,

USAID/SA will reorient its approach to strategically engage and partner with the private sector.

RDO 1: Inclusive Economic Growth Catalyzed

Development Hypothesis: An increase in trade and investment, coupled with the expansion of the

private sector, will act as a catalyst for inclusive economic growth in the region. Inclusive economic

growth is a prerequisite for an integrated, prosperous, and self-reliant Southern Africa.

Southern African countries continue to be challenged by high levels of poverty, unemployment

(specifically youth unemployment), and inequality. Without strong and inclusive economic growth that

meaningfully addresses poverty, unemployment, and inequality, self-reliance will be all but impossible

to achieve. Inclusive growth is economic growth that is distributed fairly across society and creates

opportunities for all. Regional economic growth has been sluggish, falling from 4 percent in 2010 to

about 1.2 percent in 2018, with projected growth of around 2.2 percent in 2019 and 2.8 percent in 2020.

These figures can be adjusted downwards significantly as a result of the yet unknown economic impact

of COVID-19. Even if regional economic growth stays at the projected levels, it is not nearly high enough

to achieve sustainable and inclusive development results. The regional development hypothesis is

based on the premise that increasing inclusive economic growth is a prerequisite for the development

and self-reliance of countries in the region.

USAID/SA will catalyze inclusive economic growth through increasing trade, increasing investment, and

expanding the private sector to ensure equal participation by all in economic growth and production.

Trade, investment, and private sector expansion are inherently regional issues that need to be

addressed at a regional level and at a regional scale, through regional programming. Increased trade

and investment and an expanded private sector stand as three of the strongest direct levers to address

the systemic development challenges and inequality faced in Southern Africa and are crucial for self-

reliance. Globally, the private sector provides around 90 percent of employment (formal and informal)

in developing countries and this is similar in Southern Africa. Private sector businesses strengthen

national and regional tax revenues which enable the public sector to set up basic and necessary

infrastructure. In addition, the private sector also provides two thirds of total investment and three

quarters of total credit to African country economies. Increased private sector trade and investment

also grows the volume of foreign currency coming into markets which strengthens growth and solidifies

economies against unexpected shocks. Increased private sector engagement with U.S.-based businesses

also strengthen countries’ abilities to diversify their trade and development partners. In taking a gender-

empowering approach, USAID/SA is well-positioned to play a pivotal role in increasing women’s

12

decision-making power and representation in trade, investment, and private sector growth. Doing so

will ensure women are not just the recipients of programs and services, but agents of design, delivery,

and accountability in Southern Africa’s economic growth.

Increasing trade and investment and expanding the private sector are also high on the agenda of

regional organizations such as SADC and other bilateral and multilateral donors that align their official

development assistance to regional priorities. Through increasing regional trade, investment, and

expanding the private sector, USAID/SA will provide the region with alternative and sustainable models

of financing. Furthermore, as inclusive economic growth is catalyzed and the economies of countries in

the region start growing as a result, there will be a direct positive impact on the ability of these

countries to finance their own self-reliance.

Private Sector Engagement: PSE is a means to an end. USAID/SA will engage and partner with the

private sector in all areas to improve development results. PSE is not a development objective or IR: it is

the means through which we achieve those results and the private sector is at the very core of RDO1.

Moreover, as PSE expands to increase its role not just as a producer of economic growth, but as a

meaningful contributor to responding to development challenges in the region such as poverty

alleviation, income inequality, sustainable natural resource management, and human rights protections,

USAID/SA will continue to seek out opportunities to leverage ongoing efforts to transform PSE from just

focusing on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) to include reforming entire business models, and

ensuring that businesses actually address development challenges across sectors. Examples include the

efforts of the Global Labor Program in Lesotho where major clothing brands like Levi’s and Children’s

Place have partnered with labor unions, women’s rights organizations, and Taiwanese-owned

manufacturing companies to force a change in culture with respect to GBV within the workplace. This

example extended beyond CSR and sought to sustain a permanent change by ensuring the safety and

long-term wellness of staff within the workplace, while fighting income inequality and gender

discrimination. This approach strengthens a country’s path to J2SR as the achievement of development

goals becomes a shared responsibility with the private sector. While core PEPFAR programming has a

focus on buttressing the public sector to deliver HIV services, engaging the private sector to deliver

innovative health services and serve hard-to-reach populations is of paramount importance to the South

Africa Mission. South Africa has been a leader in recognizing that one-size-fits all health services

become a barrier to best serving individual needs, pioneering Differentiated Service Delivery

6

models

that utilize the private sector to deliver client-centered services. One prominent example is the Central

Chronic Medication Dispensing and Distribution (CCMDD) model, which uses private sector logistics

companies to dispense chronic medicines (including HIV and TB medication) outside of public health

facilities at alternate pickup points. Over the course of the RDCS strategy, the emergence of South

Africa’s National Health Insurance (NHI) legal and implementation framework could reshape the health

sector. USAID is uniquely positioned to assist GoSA to strengthen NHI financing and management

mechanisms that tap underutilized capacity in the private health sector to significantly broaden access

to quality health services in the country.

Financing Self Reliance: FSR is a cornerstone of the J2SR. It is critical to adopt a holistic approach to

assessing the range of interrelated and interconnected elements that contribute to a country’s ability to

transparently and inclusively resource its own development. A quick assessment of the J2SR Regional

Landscape Analysis illustrates that countries in the region perform relatively poorly in governmental

capacity, and specifically in government and tax system effectiveness. By increasing trade and

investment, and expanding the private sector, RDO1 contributes significantly towards FSR by moving

6

http://www.differentiatedcare.org/

13

away from traditional Domestic Resource Mobilization (DRM) approaches that have centered on public

revenues, to one that targets and advances the spectrum of public and private resources. This enables

countries in the region to more effectively finance their own social and economic development through:

(1) contributing to systems that mobilize, allocate, and spend public resources effectively, efficiently,

equitably, and with accountability; (2) improving the enabling environment that allows the private

sector and domestic philanthropy to grow and thrive; and (3) developing liquid, diverse, and well-

regulated financial markets that support growth and development.

Redefining the Relationship (RDR): Southern African host country governments and intergovernmental

organizations are key stakeholders within the larger market system of trade, investment, and expanding

the private sector. As key stakeholders, USAID/SA will also look to the public sector to mobilize

resources efficiently to unlock capital for development and blend financial resources with development

resources.

RDO Regional Rationale: Regional integration remains an economic and political priority for Southern

African countries, as evidenced in their adoption and implementation of many regional integration

programs both at continental and regional levels. RDO1 seeks to catalyze inclusive economic growth

through trade, investment and expanding the private sector which forms the foundation of the regional

integration agenda and are inherently regional issues that need to be addressed at a regional level, at a

regional scale, and through regional programming.

Accelerating Commitment and Capacity: RDO1 accelerates and advances the levels of commitment and

capacity across the region at multiple levels. Activities focusing on increasing trade, investment and

expanding the private sector will not only build the capacity of local and intraregional organizations,

governments and the private sector to increase trade and investment across the region it will also

systematically address enabling environment within which trade and investment takes place leading to

long term sustainability of the system. Identifying and resolving these enabling environment

constraints, whether access to finance, limited infrastructure, high costs of trade, policy barriers, border

clearance challenges etc. will further will further enable scalable growth by ensuring that all businesses

and investments focusing on these opportunities can grow more quickly and more viably, not just those

with targeted investment support. Commitment and capacity will further be strengthened through

forming partnerships with local stakeholders such as business associations, private sector bodies,

investor bodies and business support networks to strengthen the overall private sector ecosystem. This

will ensure that local actors are able to own and drive trade and investment related activities.

Link to SA Bilateral Programming: Ongoing bilateral economic growth activities will continue to

contribute to RDO1. It is envisioned however that South Africa, as the most advanced economy in the

region, will contribute significantly towards increasing regional trade and investment and expanding the

private sector. The size and diversification of South Africa’s private sector positions it well as a lever for

extended regional trade and investment. Extending South Africa’s engagement in regional trade and

investment will also expand the resources to use for long-term growth, helping to achieve the objectives

of self-reliance of countries in the region as outlined in the J2SR. RDO1 will actively seek to partner with

South Africa, and seek out opportunities for truly mutually beneficial regional trade and investment. For

example, a stepwise approach (with e.g., gradual removal of protective measures as competitiveness

improves) will achieve trade that is not only bigger and more free (fewer monetary and non-monetary

barriers) but importantly, reciprocal and equitable, which will help the region as a whole to grow, rather

than just change/redistribute flows. Building stronger partnerships between partners in South Africa

and other Southern African geographies will be vital for this success to instill the trust and mutual

engagement needed for RDO1.

14

Donor Coordination: There are numerous trade, investment and private sector activities being

implemented by donors both at a regional level and a bilateral level within Southern Africa. Where

feasible USAID/SA will ensure that projects and activities that contribute to RDO1 does not duplicate

what other donors are already doing, and where donors have a comparative advantage USAID/SA will

explore innovative ways of partnering and supplementing with those donors. As mentioned earlier

donor coordination is important, especially considering USAID/SA’s limited resources. To this end,

USAID/SA will over the course of this strategy, form or join, sector specific donor coordination forums.

Regional Risks and Assumptions

Risks:

● Changes in U.S. Government policy;

● USAID has overestimated its convening capacity;

● External economic shocks, such as the current global COVID-19 pandemic, severely damages the

economies in the region and countries struggle with recovery for a prolonged time period.

Assumptions:

● Regional economies are resilient enough to swiftly recover from the impact of COVID-19 and

does not enter a long period of recession;

● Regional integration, trade and investment remains a top priority for SADC and countries in the

region;

● The current U.S. policies and emphasis on market-based development, private sector

engagement and mutually beneficial trade and investment does not change;

● The private sector has an appetite for engaging in development related issues beyond

traditional Corporate Social Investment (CSI) and CSR strategies.

Learning Agenda: RDO1 will seek to develop a knowledge base on what approaches to increasing trade,

investment and expanding the private sector work best in a regional setting. The learning agenda will

also seek to answer specific questions on the effectiveness of increasing trade, investment, and

expanding the private sector as a catalyst for inclusive growth. More broadly, the learning agenda will

contribute to the broader learning agenda of the Agency on PSE effectiveness and contribute to the

body of evidence and best practice for improved PSE programming among USAID and other

development actors. Illustrative learning questions include:

● What evidence supports that increasing trade contributes to inclusive economic growth?

● What is USAID’s role in mobilizing private capital? What approaches are most efficient?

● What is the correlation between increasing investment and improved development results?

● What is the correlation between structuring innovative and blended finance models and private

sector expansion?

IR 1.1: Trade Increased: Trade contributes to sustainable economic growth, job creation, productivity

gains, higher incomes, improved health outcomes, greater food security, women’s empowerment,

better governance, and many other development objectives. A large body of empirical evidence

demonstrates that increasing trade stimulates investment, increases productivity, and generates

significantly higher revenues and incomes for firms and workers connected to international or regional

value chains. Promoting regional economic growth through trade also has economic and strategic

benefits for the U.S., including increasing market access and opportunities for U.S. companies in

Southern Africa.

15

The informal cross-border trade sector provides unique opportunities to improve women’s equal

participation in economic growth, production, and trade in the region. Women make up 70 percent of

all informal traders taking part in informal cross-border trade in SADC. The economic activity of these

women accounted for over $17.6 billion

7

and enabled important regional linkages that promote

economic interdependence and regional food security. However, the disproportionately high role that

women play in informal trade means that they are disproportionately impacted by the challenges that

the sector faces overall. Informal traders can end up paying more in border fees to clear goods

compared to larger traders which reduces their profitability, potential for scale and economic growth.

In trade, women are also more susceptible to sexual or financial extortion from officials. This

compromises their safety and ease of doing business. These challenges arise from not only a largely

male dominated customs and border system but in the general lack of awareness from female traders of

the policies and rights that are guaranteed.

Along with increased trade are risks related to increased pollution, natural habitat fragmentation, and

carbon production.

8

To mitigate these risks and increase trade, USAID/SA will focus on implementing

responsible trade agreements, facilitating trade flows, and enhancing economic responsiveness of

businesses to take advantage of trade opportunities and protect the region’s natural resources.

USAID/SA will facilitate intra-regional trade and two-way trade between the U.S. and Southern Africa in

sectors where there are strong market opportunities with high levels of innovation, productivity,

competitiveness, collaboration (including industry concentration). Sector social inclusivity (such as

gender and youth), business practices that are built on environmental sustainability, and strong value-

chain linkages as well as the feasibility and sustainability of impact, will drive the identification of target

sectors.

USAID/SA will prioritize the identification of the product-market combinations (macro-economic

opportunities) across Southern Africa with high potential for growth and impact. A systems approach

will be used to identify the binding constraints which limit their growth and/or hinder their development

impact, which can be opportunity-specific or related to the overall ecosystem. This approach will

surface more, and better, macro-economic opportunities for trade; will more clearly identify and

support the potential for development impact of these opportunities; and will also highlight the

additional work and investment needed to increase viability. Identifying and resolving the binding

constraints for high-potential macro-economic opportunities, whether access to finance, limiting

infrastructure, high costs of trade, policy barriers, border clearance challenges or others, will further

enable scalable growth by ensuring that all businesses and investments focusing on these opportunities

can grow more quickly and more viably, not just those with targeted investment support.

Achieving scalable and sustainable growth requires a supportive ecosystem that both creates and

actively implements supportive trade policies, laws, and regulations. USAID/SA will address the

challenges linked to specific trade policies, regulations, and behaviors by increasing alignment and

implementation particularly. USAID/SA will aim to drive new ecosystem innovations such as additional

financing platforms (e.g., Development Impact Bonds (DIB)s and Social Impact Bonds (SIBs)), particularly

for onward and second-stage financing, and de-risking models (e.g. credit guarantees and blended

finance options) which will increase the likelihood of successful trade and also generate new and

innovative growth in the wider private sector. Collectively, USAID/SA will leverage South Africa’s

7

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), “Borderline: Women in informal cross-border

trade in Malawi, the United Republic of Tanzania, and Zambia”, 2019

8

USAID Southern Africa Tropical Forestry and Biodiversity Assessment, November 2017

16

relative strength and economic stability as a catalyst for strengthening the enabling environment of

other Southern African countries.

Agriculture production remains central to poverty reduction, economic growth, and food and nutrition

security in Southern Africa, despite it being a water-scarce region. Agriculture provides a livelihood

including subsistence, employment, and income and wealth creation for over 60 percent of the region’s

250 million people, and contributes eight percent of the region’s GDP, or over 28 percent when all

middle-income countries are excluded. Most smallholder farmers in the region are women who

produce crops which have enormous potential for increased trade between African countries and within

global markets. Within SADC countries, women contribute more than 60 percent to total food

production and provide the largest labor force in the agriculture sector. As such, the agriculture sector

and women’s roles in agriculture will remain a priority and since it is predicted that by 2050 the region

will have 20 percent less rainfall to replenish its surface and subsurface stocks, increased attention and

support for water resource management is necessary. In addition, there is a growing interest by the

private sector in the region, to invest in agriculture. These emerging agricultural entrepreneurial

interests can be harnessed to advance regional harmonization and reform efforts to reduce poverty and

hunger in the region through accelerated agricultural value chain development. The agricultural sector

is one of the highest contributors of Greenhouse Gases (GHG) in the region. Therefore, programs

implemented under this IR must consider ways of reducing GHG emissions. Climate risks will affect the

agricultural sector and therefore may thwart efforts to increase trade of agricultural products. To

address climate risks, USAID will partner with private companies and donors to assist the sector to be

more climate resilient, partner with firms that practice sustainable agricultural methods, ensure that

trading partners have the capacity and systems in place to mitigate logistical challenges due to climate-

related crises, and encourage climate resiliency of firms that will be supported under this IR.

IR1.2: Investment Increased: The importance of investment for economic growth can not be overstated.

Investment leads to productivity improvements, which in turn leads to economic growth. Investment in

infrastructure (e.g. water and sanitation) enables the private sector to use technology to expand

productive activities. Investment in education and human capital produces a more skilled and

productive labor force. Investment in health enables a healthier labor force which leads to increased

productivity. Identifying gender-empowering growth sectors and opportunities (e.g., trade corridors)

should include a prioritization based on the direct and indirect empowerment for women. Directly,

opportunities for women should prioritize both increases and diversification of jobs, along with data and

evidence on what sectors may inherently further aggravate gender inequalities. This should start with a

clear identification and prioritization of female dominant sectors or value chains. This will allow

activities to direct resources and growth to existing opportunities where women currently capture the

greatest value. Investing in and growing these opportunities will increase women’s direct participation,

expertise, and agency in the given sector. Opportunity prioritization should also identify and support

sectors that stand to benefit women equally, if not greater. Some sectors inherently favor men over

women, and vice versa, which can lead to greater gender disparities as investment and growth occur. In

addition to this, some women don’t necessarily benefit from sector diversification. For instance,

investing in agricultural processing may greatly help regional economic growth, but could do so through

the disproportionate exclusion of women, who often do not take part in businesses or production at the

higher end of the agricultural value chains. Indirect benefits for women from sector growth—such as

increased access to nutrition, health, financial independence, and others, should also be examined and

supported.

Moreover, investment enables businesses to expand and grow, creating employment opportunities and

generating products and services, all of which have a multiplier effect in the value chain. In terms of

17

volume, foreign and local private investment has far outpaced traditional development assistance,

which is steadily decreasing. There is an estimated global financing gap of between $2.5 - $3 trillion a

year to reach the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), while the gross world product is estimated at

$80 trillion, and global gross private sector financial assets are estimated at $200 trillion. For

development, it is crucial that the capital that is available is leveraged and channeled more effectively

towards inclusive growth and addressing various development challenges. To this end, USAID/SA will

focus on increasing investment between Southern African countries, and from sources external to the

region, especially the U.S., to drive regional growth and development. USAID/SA will leverage its

financial resources efficiently and effectively to attract additional investment across numerous sectors

including agriculture, education, water and sanitation, environment, and energy. To mitigate the

impacts of climate change, USAID/SA will encourage climate resiliency to be built into investment

portfolios supported through its programs.

USAID/SA will prioritize the identification of the product-market combinations (macro-economic

opportunities) across Southern Africa with high potential for growth and impact. A systems approach

will be used to identify the binding constraints which limit their growth and/or hinder their development

impact, which can be opportunity-specific or related to the overall ecosystem. This approach will

surface more, and better, macro-economic opportunities for investment, will more clearly identify and

support the potential for the development impact of these opportunities, and will also highlight the

additional work and investment needed to increase viability. Identifying and resolving the binding

constraints for high-potential macro-economic opportunities, whether access to finance, limiting

infrastructure, high costs of trade, policy barriers, border clearance challenges or others, will further

enable scalable growth by ensuring that all businesses and investments focusing on these opportunities

can grow more quickly and more viably, not just those with targeted investment support.

Achieving scalable and sustainable growth requires a supportive ecosystem that both creates and

actively implements supportive investment policies, laws, and regulations. USAID/SA will address the

challenges linked to specific trade policies, regulations, and behaviors particularly by increasing

alignment and implementation. USAID/SA will drive new ecosystem innovations such as additional

financing platforms (e.g., DIBs and SIBs), particularly for onward and second-stage financing, and de-

risking models (e.g., credit guarantees and blended finance options) which will increase the likelihood of

successful trade and also generate new and innovative growth in the wider private sector. Collectively,

USAID/SA will leverage South Africa’s relative strength and economic stability as a catalyst for

strengthening the enabling environment of other Southern African countries.

USAID/SA will also focus on converting identified opportunities within a pipeline into successfully

completed transactions. Successfully closing deals often requires transactional support. Transactional

support is particularly effective if opportunities fall into new or challenging environments for investors.

In these situations, investors are inclined to back out should the upfront transactional work be overly

complex or require a greater deal of effort than usual or anticipated. Providing additional support in the

form of transaction facilitation support, feasibility analyses, and due diligence investigations can often

be a “make or break” to help carry proposed trade and investment opportunities through to successful

closing. Activities that apply individual de-risking instruments developed in previous phases will further

increase the likelihood of successful transaction completion.

IR.1.3: Private Sector Expanded: It is generally acknowledged that a robust and vibrant private sector is

necessary for effective and sustained growth. A growing private sector is a major source of wealth, job

creation, dynamism, competitiveness, and knowledge diffusion, all of which lead to long-term growth.

The private sector is an essential partner in advancing the process of women’s economic empowerment.

Strengthened by greater trade and investment and gender-empowerment support, greater private

18

sector engagement can result in step-change for women by adopting business practices that include and

support women as workers, consumers, producers and suppliers. This is most notably true when the

private sector directs its many assets, such as in-house expertise and financial resources, into sectors

that disproportionately employ and empower women. USAID/SA will strategically consult, strategize,

collaborate, and implement with the private sector for greater scale, sustainability, and effectiveness of

development outcomes. Doing so will directly increase women’s employment opportunities and will

indirectly increase opportunities for women to strengthen and diversify their presence along critical

commodity value chains—particularly through female-owned SMEs. Building stronger and more patient

and long-term partnerships with governments, civil society, NGOs and international institutions will

further extend the scale and impact of gender-forward investment and will deepen levels of trust

between the private sector and women across Southern Africa.

This will enable USAID/SA to leverage private sector expertise, innovation, and resources across sectors

in Southern Africa to build country-level capacity for self-reliance. USAID/SA will partner with the

private sector to improve development outcomes including health, economic growth, education, water

and sanitation, environment, and democracy, human rights, and governance. Partnerships can and will

take various forms and do not necessarily have to be formalized. It is critical that USAID/SA provide

assistance to expand and grow the private sector, specifically innovative businesses which produce

public or social goods and services efficiently and are inclusive in nature. Emphasis on inclusion is

critical since at least seven countries in the region fall within the top 10 most unequal countries in the

world in 2019, according to the World Bank, with South Africa at number one. Expansion of the private

sector must take into consideration the needs and priorities of marginalized and under-represented

groups, the rights of workers, and mitigate opportunities for TIP and GBV in the workplace. Expansion

should be targeted; identifying those sectors with the greatest probability to contribute towards poverty