Marshall Ganz’ Framework

PEOPLE, POWER AND CHANGE

RESTRICTIONS OF USE

The following work is provided to you pursuant to the following terms and conditions. Your acceptance of the work

constitutes your acceptance of these terms:

• You may reproduce and distribute the work to others for free, but you may not sell the work to others.

• You may not remove the legends from the work that provide attribution as to source (i.e., “originally adapted from

the works of Marshall Ganz of Harvard University”).

• You may modify the work, provided that the attribution legends remain on the work, and provided further that you

send any significant modifications or updates to marshall_ganz@harvard.edu or Marshall Ganz, Hauser Center,

Harvard Kennedy School, 79 JFK Street, Cambridge, MA 02138

• You hereby grant an irrevocable, royalty-free license to Marshall Ganz and New Organizing Institute, and their

successors, heirs, licensees and assigns, to reproduce, distribute and modify the work as modified by you.

• You shall include a copy of these restrictions with all copies of the work that you distribute and you shall inform

everyone to whom you distribute the work that they are subject to the restrictions and obligations set forth herein.

If you have any questions about these terms, please contact marshall_ganz@harvard.edu or Marshall Ganz, Hauser Center,

Harvard Kennedy School, 79 JFK Street, Cambridge, MA 02138.

!

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard!University!and!modified!by!Jacob!Waxman.!

2

Organizing can be learned as a leadership practice based on accepting responsibility for enabling others to

achieve purpose under conditions of uncertainty: identifying, recruiting and developing leadership, building a

constituency around that leadership, and transforming the resources of that constituency into the power they

need to achieve their purposes. !

There are five basic organizing leadership practices.

1. How to translate values into the motivation for action by learning to tell a story of why they were called

to lead, a story of their constituency, and a story of an urgent challenge that requires action: self, us,

and now.

2. How to build intentional relationships as the foundation of purposeful collective action.

3. How to structure a collaborative leadership team with shared purpose, ground rules and clear roles.

4. How to strategize turning the resources of one’s constituency into the power needed to achieve clear

goals.

5. How to secure commitments required to generate measurable, motivational, and effective action.

What is Leadership?

Leadership in organizing is rooted in three questions articulated by the first century Jerusalem sage, Rabbi Hillel:

“If I am not for myself, who am I?

When I am only for myself, what am I?

And if not now, when?

1

These three questions focus on the interdependence of self, other, and action: what am I called to do, what are

others with whom I am in relationship called to do, and what action does the world in which we live demand of us

now?

The fact these are framed as questions, not answers, is important: to act is to enter a world of uncertainty, the

unpredictable, and the contingent. Do we really think we can control it? Or do we have to learn to embrace it?

Uncertainty poses challenges to the hands, the head and the heart. What new skills must my “hands” learn? How

can my “head” devise new ways to use my resources to achieve my goals? How can my “heart” equip me with

the courage, hopefulness, and forbearance to act?

Leadership requires “accepting responsibility for enabling others to achieve purpose under conditions of

uncertainty”.

2

Conditions of uncertainty require the “adaptive” dimension of leadership: not so much performing

known tasks well, but, rather learning what tasks are needed and performing them well. It is leadership from the

perspective of a “learner” – one who has learned to ask the right questions – rather than that of a “knower” – on

who thinks he or she knows all the answers. This kind of leadership is a form of practice - not a position or a person

– and it can be exercised from any location within or without a structure of authority.

Leadership is taking responsibility for enabling others to achieve shared purpose under conditions of uncertainty.

1

Pirke Avot (Wisdom of the Fathers)

2

Marshall Ganz, “Leading Change: Leadership, Organization and Social Movements”, Chapter 19,

!

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard!University!and!modified!by!Jacob!Waxman.!

3

We also take a particular approach to structuring leadership, a structure that enables us to develop the leadership

of others, even as we exercise our own. Sometimes we think leadership is about being the person that everyone

goes to.

How does it feel to be the dot in the middle of all those arrows? How does it feel to be one of the arrows that

can’t even get through? And what happens if the “dot” in the middle should disappear? Sometimes we think we

don’t need leadership at all because “we’re all leaders”, but that looks like this:

Who’s responsible for coordinating everyone? And who’s responsible for focusing on the good of the whole, not

just one particular part? With whom does the “buck stop”?

Another way to practice leadership is like this “snowflake”: leadership practices by developing other leaders who,

in turn, develop other leaders, all the way “down”. Although you may be the “dot” in the middle, your success

depends on developing the leadership of others.

What is Organizing?

Organizing is a form of leadership that enables a constituency to turn its resources into the power to achieve its

goals through recruitment, training, and development of leadership. Organizing is about equipping people

(constituency) with the power (story and strategy) to make change (real outcomes).

PEOPLE

: Organizing a constituency

The first question an organizer asks is not “what is my issue” but “who are my people” – who is my constituency.

A constituency is a group of people who learn to “stand together” to decide, assert, and act upon their own

goals. Organizing is not only about solving problems. It is about enabling the people with the problem to mobilize

their own resources to solve it . . . and keep it solved.

POWER

: What is it, where does it come from, how does it work?

Rev. Martin Luther King described power as the “ability to achieve purpose.” We all require resources to achieve

our purposes. Few if any of us control all the resources we need to achieve all our purposes. But your interest in

my resources and my interest in your resources may give us a common interest in combining our resources to

achieve a common purpose (power with). But if I need your resources more than you need my resources, you may

be able to get what you need at my expense (power over). So power is not a thing, quality, or trait – it is the

influence created by the relationship between interests and resources. You can “track down the power” asking—

and getting the answers to—four questions:

1. What are the interests of your constituency?

2. Who holds the resources needed to address these interests?

3. What are the interests of the individuals or organizations who hold these resources?

!

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard!University!and!modified!by!Jacob!Waxman.!

4

4. What resources does your constituency hold which the other individuals or organizations need to

address their interests?

Our power comes from people. Because powerlessness is the source of so many of the problems people face,

organizing not only enables people to solve those problems, but also, by working together, to become more

powerful people.

So organizing is not only a commitment to identify more leaders, but also a commitment to engage those leaders

in building the power to create the change we need in our lives. Organizing power begins with a decision by the

first person who wants to make it happen to commit. Without this commitment, there are no resources with which

to begin. Commitment is as observable as action. The work of organizers begins with a decision to accept respon-

sibility to challenge others to do the same.

CHANGE

: What kind of change can organizing make?

What urgent problems do your people face? How might the world look different if those problems were solved?

What first steps can they take to begin solving those problems? Change is specific, concrete, and significant. It

requires focus on a goal that will make a real difference that we can see. It is not about “creating awareness”,

having a meaningful conversation, or giving a great speech. It is about specifying a clearly visible goal, explaining

why achieving that goal can make a real difference in meeting the challenge that your constituency has to face,

and making it happen.

1. Creating Shared Story:

Organizing is motivated by shared values expressed through public narrative. By learning the craft of public

narrative we can access our shared values for the emotional resources we need to respond to challenges with

courage rather than reacting to them with fear. By learning to tell stories of sources of our own values, a “story of

self”, we enable people to “get us”. By telling stories of the sources of values we share, a “story of us”, we enable

people to “get” each other. By recognizing the current moment as one of urgent choice and proposing a hopeful

way forward, a “story of now”, we motivate action. Values-based organizing—in contrast to issue-based

organizing—invites people to escape their “issue silos” and come together so that their diversity becomes an

asset, rather than an obstacle. By learning how to tell a public narrative that bridges the self, us, and now,

organizers enhance their own efficacy and create trust and solidarity within their campaign, equipping them to

engage others far more effectively.

2. Creating Shared Relational Commitment:

Organizing is based on relationships and creating mutual commitments to work together. It is the process of

association—not simply aggregation—that makes a whole greater than the sum of its parts. Through association

we can learn to recast our individual interests as common interests, identify values we share, and envision

objectives that we can use our combined resources to achieve. And because it makes us more likely to act to

assert those interests, relationship building goes far beyond delivering a message, extracting a contribution, or

!

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard!University!and!modified!by!Jacob!Waxman.!

5

soliciting a vote. Relationships built as a result of one-on-one meetings create the foundation of local campaign

teams, and they are rooted in commitments people make to each other, not simply commitment to an idea, task,

or issue.

3. Creating Shared Structure

A team leadership structure can enable organizing that grows stronger through collaborative and cascading

leadership development. Volunteer efforts often flounder due to a failure to develop reliable, consistent, and

creative individual leaders. Structured leadership teams encourage stability, motivation, creativity, and

accountability—and use volunteer time, skills, and effort effectively. They create a structure within which energized

volunteers can accomplish challenging work. Real teams can achieve the goals they set for themselves, grow more

effective as a team over time, and enable the growth, development and learning of their individual members.

Effective leadership teams must be bounded, stable, and diverse. They must agree on a shared purpose, clear

norms, and specific roles.

4. Creating Shared Strategy

Although based on broad values, effective organizing campaigns focus on a clear strategic objective, a way to

turn those values into action; e.g., desegregate buses in Montgomery, Alabama; getting to 100% clean electricity;

etc. Trans-local campaigns locate responsibility for strategy at the top (or at the center), but are able to “chunk

out” strategic objectives in time (deadlines) and space (local areas) as a campaign, allowing significant local

responsibility for figuring out how to achieve those objectives. Responsibility for strategizing local objectives

empowers, motivates and invests local teams.

5. Creating Shared Measurable Action

Organizing outcomes must be clear, measurable, and specific if progress is to be evaluated, accountability

practiced, and strategy adapted based on experience. Measures may include volunteers recruited, money raised,

people at a meeting, voters contacted, pledge cards signed, laws passed, etc. Although electoral campaigns

enjoy the advantage of very clear outcome measures, any effective organizing drive must come up with the

equivalent. Regular reporting of progress to goal creates opportunity for feedback, learning, and adaptation.

Training must be provided for all skills (e.g., holding house meetings, phone banking, etc.) to carry out the

program. Social media may help enable reporting, feedback, coordination. Transparency must exist as to how

individuals, groups, and the campaign as a whole are doing with regard to their progress toward their goal.

---

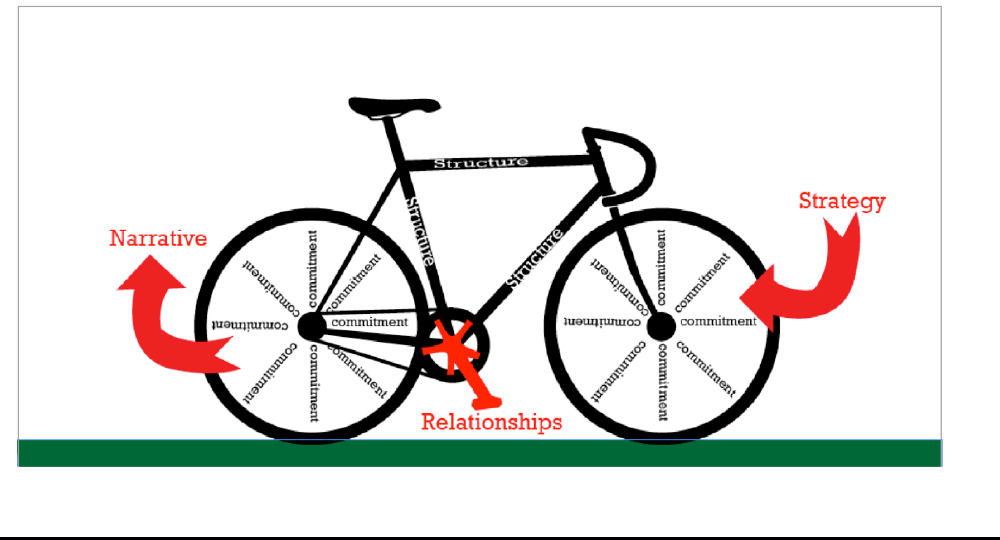

Learning Organizing

Organizing is a practice—a way of doing things. It’s like learning to ride a bike. No matter how many books you

read about bike riding, they are of little use when it comes to getting on the bike.

!

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard!University!and!modified!by!Jacob!Waxman.!

6

And when you get on the first thing that will happen is that you will fall. And that’s where the “heart” comes in.

Either you give up and go home or you find the courage to get back on, knowing you will fall, because that’s the

only way to learn to keep your balance.

Each of our sessions will follow the same pattern: explanation, modeling, practice, and debriefing.

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

7

INTRODUCTION TO PUBLIC NARRATIVE & STORY OF SELF

If I am not for myself, who will be for me?

When I am only for myself, what am I?

If not now, when?

- Hillel, 1

st

century Jerusalem sage

Crafting a complete public narrative is a way to connect

three core elements of leadership practice: story (why we

must act now, heart), strategy (how we can act now, head),

and action (what we must do to act now, hands). As Rabbi

Hillel’s powerful words suggest, to stand for yourself is a

first but insufficient step. You must also construct the

community with whom you stand, and move that

community to act together now. To combine stories of self,

us and now, find common threads in values that call you to

your mission, values shared by your community, and

challenges to those values that demand action now. You

may want to begin with a Story of Now, working backward through the Story of the Us with whom you are working

to the Story of Self in which your calling is grounded.

Public narrative as a leadership practice

Leadership is about accepting responsibility for enabling others to achieve shared purpose in the face of

uncertainty. Narrative is how we learn to access the moral resources – the courage – to make the choices that

shape our identities – as individuals, as communities, as nations.

Each of us has a compelling story to tell

Each of us can learn to tell a story that can move others to action. We each have stories of challenge, or we

wouldn’t think the world needed changing. And we each have stories of hope, or we wouldn’t think we could

change it. As you learn this skill, you will learn to tell a story about yourself (story of self), the community whom

you are organizing (story of us), and the action required to create change (story of now). You will learn to tell, to

listen, and to coach others.

Learning Public Narrative

We are all natural storytellers. We are “hard wired” for it. Although you may not have learned how to tell stories

“explicitly” (their structure, the techniques), you have leaned “implicitly” (imitating others, responding to the way

others react to you, etc.). In this workshop you will learn the tools to make the implicit explicit. We will use a four-

stage pedagogy: explain, model, practice and debrief. We will explain how story works, you will observe a model

of story telling, you will then practice you own story, and you will then debrief your practice with others.

strategy & actioncall to leadership

shared values &

shared experience

story of

self

story of

now

story of

us

PURPOSE

COMMUNITY

URGENCY

Public Narrative

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

8

You will learn this practice the way we learn any practice: the same way we learn to ride a bike. Whatever we read,

watch, or are told about bike riding, sooner or later we have to get on. And the first thing that usually happens is

that you fall off. Then, and this is the key moment, you either give up or find the courage to get back up on the

bike, knowing you will continue to fall, until, eventually you learn to keep your balance. In this workshop you’ll

have the support of your written materials, peers and coaches.

You will also learn to coach others in telling their stories. We are all “fish” so to speak in the “water” of our own

stories. We have lived in them all our lives and so we often need others to ask us probing questions, challenge us

to explain why, and make connections we may have forgotten about so we can tell our stories in ways others can

learn from them.

We all live rich, complex lives with many challenges, choices, and outcomes of both failure and success. We can

never tell our whole life story in two minutes. We are learning to tell a two-minute story as the first step in

mastering the craft of public narrative. The time limit focuses on getting to the point, offering images rather than

lots of words, and choosing choice points strategically.

How Public Narrative Works

Why use public narrative? Two ways of knowing (and why we

need both!)

Leadership requires engaging the “head” and the “heart” to

engage the “hands”—mobilizing others to act together

purposefully. Leaders engage people in interpreting why they

should change their world—their motivation—and how they can

act to change it—their strategy. Public narrative is the “why”—

the art of translating values into action through stories.

The key to motivation is understanding that values inspire

action through emotion.

Emotions inform us of what we value in ourselves, in others, and in the world, and enable us to express the

motivational content of our values to others. Stories draw on our emotions and show our values in action, helping

us feel what matters, rather than just thinking about or telling others what

matters. Values are powerfully communicated not in a mission

statement but through storytelling that draws on the evidence of particular

moments of lived experience. Because stories allow us to express our values

not as abstract principles, but as lived experience, they have the power to

move others.

Some emotions inhibit action, but other emotions facilitate action.

g

head

strategy

Two Kinds of Knowin

heart

narrative

hands

action

shared

understanding

leads to

critical reflection

on experience

HOW

COGNITIVE

LOGOS

ANALYSIS

story telling

of experience

WHY

AFFECTIVE

PATHOS

MOTIVATION

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

9

The language of emotion is the language of movement, sharing the same root word. Mindful action is inhibited

by inertia and apathy, on the one hand, and fear, isolation and self-doubt on the other. It can be facilitated by

urgency and anger, on one hand, and hope, solidarity, and YCMAD (you can make a difference) on the other.

Stories can mobilize emotions enabling mindful action to overcome emotions that inhibit it.

The Three Key Elements of Public Narrative Structure: Challenge – Choice – Outcome

A plot begins with an unexpected challenge that confronts a character

with an urgent need to pay attention, to make a choice, a choice for

which s/he is unprepared. The choice yields an outcome—and the

outcome teaches a

moral.

Because we can

empathetically

identify with the

character, we can

“feel” the moral. We

not only hear “about”

someone’s courage; we can also be inspired by it.

The story of the character and their effort to make choices

encourages listeners to think about their own values, and

challenges, and inspires them with new ways of thinking about

how to make choices in their own lives.

Incorporating Challenge, Choice, and Outcome in Your Own Story

There are some key questions you need to answer as you consider the choices you have made in your life and the

path you have taken that brought you to this point in time as a leader. Once you identify the specific relevant

choice point—perhaps your first true experience of community in the face of challenge, or your choice to do

something about injustice for the first time—dig deeper by answering the following questions.

Challenge

: Why did you feel it was a challenge? What was so challenging about it? Why was it your challenge?

Choice

: Why did you make the choice you did? Where did you get the courage (or not)? Where did you get the

hope (or not)? Did your parents or grandparents’ life stories teach you in any way how to act in that moment?

How did it feel?

Outcome

: How did the outcome feel? Why did it feel that way? What did it teach you? What do you want to teach

us? How do you want us to feel?

OVERCOMES

inertia

solidarity

urgency

apathy anger

fear hope

self-doubt Y.C.M.A.D.

isolation

ACTION

INHIBITORS

ACTION

MOTIVATORS

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

10

A word about challenge: Sometimes people see the word challenge and think that they need to describe the

misfortunes of their lives. Keep in mind that a struggle might be one of your own choosing – a high mountain

you decided to climb as much as a valley you managed to climb out of. Any number of things may have been a

challenge to you and be the source of a good story to inspire others.

Public narrative combines a story of self, a story of us, and a story of now.

A “story of now” communicates an urgent challenge you are calling

on your community to join you in acting on now.

A story of now requires telling stories that bring the urgency of the

challenge you face alive – urgent because of a need for change that

cannot be denied, urgent because of a moment of opportunity to

make change that may not return. At the intersection of the urgency

of challenge and the promise of hope is a choice that must be made

– to act, or not to act; to act in this way, or in that. The hope resides

not somewhere in a distant future but in the sense of possibility in a

pathway to action. Telling a good story of now requires the courage

of imagination, or as Walter Brueggemann named it, a prophetic

imagination, in which you call attention both to the pain of the world

and also to the possibility for a better future.

A “story of us” communicates shared values that anchor your

community, values that may be at risk, and may also be sources of hope.

We tell more “stories of us” in our daily lives than any other kind of story: “do you remember when” moments at

a family dinner, “what about the time that” moments after an exciting athletic event, or simply exchanging stories

with friends. Just like any good story, stories of us recount moments when individuals, a group, a community, an

organization, a nation experienced a challenge, choice, and outcome, expressive of shared values. The may be

founding moments, moments of crisis, of triumph, disaster, of resilience, of humor. The key is to focus on telling

specific stories about specific people at specific times that can remind everyone of–or call everyone’s attention

to–the values that you share against which challenges in the world can be measured. A “story of us”, however, is

“experiential” in that it creates an experience of shared values, rather than “categorical”, described by certain

traits, characteristics, or identity markers. Telling a good story of us requires the courage of empathy – to consider

the experience of others deeply enough to take a chance of articulating that experience.

A “story of self” communicates the values that called you to lead in this way, in this place, at this time.

Each of us has compelling stories to tell. In some cases, our values have been shaped by choices others – parents,

friends, and teachers – have made. And we have chosen how to deal loss, even as we have found access to hope.

Our choices have shaped our own life path: we dealt with challenges as children, found our way to a calling,

responded to needs, demands, and gifts of others; confronted leadership challenges in places of worship,

schools, communities, work

For Further Reflection

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

11

We all live very rich and complex lives with many challenges, many choices, and many outcomes of both failure

and success. That means we can never tell our whole life story in 2 minutes. The challenge is to learn to interpret

our life stories as a practice, so that we can teach others based on reflection and interpretation of our own

experiences, and choose stories to tell from our own lives based on what’s appropriate in each unique situation.

Take time to reflect on your own public story, beginning with your story of self. You may go back as far as your

parents or grandparents, or you may start with your most recent organizing and keep asking yourself why in

particular you got involved when you did. Focus on challenges you had to face, the choices you made about how

to deal with those challenges, and the satisfactions – or frustrations—you experienced. Why did you make those

choices? Why did you do this and not that? Keep asking yourself why.

What did you learn from reflecting on these moments of challenge, choice, and outcome? How do they feel? Do

they teach you anything about yourself, about your family, about your peers, your community, your nation, your

world around you—about what really matters to you? What about these stories was so intriguing? Which

elements offered real perspective into your own life?

What brings you to this campaign? When did you decide to work on improving education, for instance? Why?

When did you decide to volunteer? Why? When did you decide to give up a week to come to this workshop?

Why?

Many of us active in public leadership have stories of both loss and hope. If we did not have stories of loss, we

would not understand that loss is a part of the world; we would have no reason to try to fix it. But we also have

stories of hope. Otherwise we wouldn’t be trying to fix it.

A good public story is drawn from the series of choice points that structure the “plot” of your life – the challenges

you faced, choices you made, and outcomes you experienced.

Challenge: Why did you feel it was a challenge? What was so challenging about it? Why was it your challenge?

Choice: Why did you make the choice you did? Where did you get the courage – or not? Where did you get the

hope – or not? How did it feel?

Outcome: How did the outcome feel? Why did it feel that way? What did it teach you? What do you want to teach

us? How do you want us to feel?

BUILDING POWER THROUGH RELATIONSHIPS

Why Build Relationships? Organizing vs. Mobilizing

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

12

Leadership begins with understanding yourself: your values, your motivation, your story. But leadership is about

enabling others to achieve purpose. The foundation of this kind of leadership is the relationships built with

others, most especially, others with whom we can share leadership.

Leadership in organizing is based on relationships. This is a key difference between mobilizing and organizing.

When we mobilize we access and deploy a person’s resources, for example, their time to show up at a rally, their

ability to “click” to sign a petition (or their signature), of their money. But when we organize we are actually

building new relationships which, in turn, can become a source not only of a particular resource, but of leadership,

commitment, imagination, and, of course, more relationships. In mobilizing, the “moment of truth” is when we

ask, can I count on you to be there, give me $5.00, and sign the petition. In organizing the “moment of truth” is

when two people have learned enough about each other’s interests, resources, and values not only to make an

“exchange” but also to commit to working together on behalf of a common purpose. Those commitments, in

turn, can generate new teams, new networks, and new organizations that, in turn, can mobilize resources over and

over and over again.

1)

Identifying, Recruiting, and Developing Leadership: We build relationships with potential collaborators to

explore values, learn about resources, discern common purpose, and find others with whom leadership

responsibility can be shared.

2)

Building Community: Leaders, in turn, continually reach out to others, form relationships with them, expand

the circle of support, grow more resources that they can access, and recruit people who, in turn, can become

leaders themselves.

3)

Turning Resources into Power: Relationship building doesn’t end when action starts. Commitment is how to

access resources for organizing – especially when you come up against competition, internal conflict, or

external obstacles. Commitment is based on relationships, which must be constantly, intentionally nurtured.

The more others find purpose in joining with you the more they will commit resources that you may never

have known they had.

Coercion or Commitment?

Leaders must decide how to lead their organization or campaign. Will the glue that holds things together be a

command and control model based on coercion? Or will the glue be volunteered commitment? If our long-term

power and potential for growth comes more from voluntary commitment, then we need to invest significant time

and intentionality in building the relationships that generate that commitment—to each other and to the goals

that bring us together. That requires transparent, open and mindful interaction, not closed, reactive or

manipulating maneuvers.

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

13

What Are Relationships?

þ Relationships are rooted in shared values. We can identify values that we share by learning each other’s stories,

especially ‘choice points’ in our life journeys. The key is asking “why.”

þ Relationships grow out of exchanges of interests and resources. Your resources can address my interests; my

resources can address your interests. The key is identifying interests and resources. This means that relationships

are driven as much by difference as by commonality. Our common interest may be as narrow as supporting each

other in pursuit of our individual interest, provided they are not in conflict. Organizing relationships are not simply

transactional. We’re not simply looking for someone to meet our “ask” at the end of a one-to-one meeting or

house meeting. We’re looking for people to join with us in long-term learning, growth and action.

þ Relationships are created by commitment. An exchange becomes a relationship only when each party commits a

portion of their most valuable resource to it: time. A commitment of time to the relationship gives it a future and,

therefore, a past. And because we can all learn, grow, and change, the purposes that led us to form the relationship

may change as well, offering possibilities for enriched exchange. In fact the relationship itself may become a valued

resource – what Robert Putnam calls “social capital.”

þ Relationships involve constant attention and work. When nurtured over time, relationships become an important

source of continual learning and development for the individuals and communities that make up your campaign.

They are also a great source for sustaining motivation and inspiration.

Building Intentional Relationships: The One-on-One Meeting.

One way to initiate intentional relationships is the one-on-one meeting, a technique developed by organizers

over many years. A one-on-one meeting consists of five “acts”:

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

14

Attention

– We have to get another person’s attention to conduct a one-on-one meeting. Don’t be “coy”. Be as

up front as you can be about what your interest is in the meeting, but that first, you’d like it take a few moments

to get acquainted.

Interest

– There must be a purpose or a goal in setting up a one-on-one

meeting. It could range from, “I’m starting a new network and thought

you might be interested” to “I’m struggling with a problem and I think

you could help” or “I know you have an interest in X so I’d like to discuss

that with you.”

Exploration

– Most of the one-on-one is devoted to exploration by asking

probing questions to learn the other person’s values, interests, and

resources and by sharing enough of your own values, interests, and

resources that it can be a two-way street.

Exchange

– We exchange resources in the meeting such as information,

support, and insight. This creates the foundation for future exchanges.

Commitment

–A successful one on one meeting ends with a

commitment, most likely to meet again. By scheduling a specific time for this meeting, you make it a real

commitment. The goal of the one-on-one is not to get someone to make a pledge, to give money, to commit his

or her vote as it is to commit to continuing the relationship.

DO

DON’T

Schedule a time to have this conversation (usually

30 to 60 minutes)

Be unclear about purpose and length of

conversation

Plan to listen and ask questions

Try to persuade rather than listen and ask

questions

Follow the steps of the conversation above

Chit chat about private interests

Share experiences and deep motivations

Skip stories to “get to the point”

Share a vision that articulates a shared set of

interests for change

Miss the opportunity to share ideas about how

things can change

Be clear about the ‘when and what’ of your next

step together.

End the conversation without a clear plan for the

next steps.

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

15

BUILDING LEADERSHIP TEAMS

Why do leadership teams matter?

Most effective leaders create teams to work with them and to lead with them. Take for example Moses, Aaron

and Miriam in the story of Exodus, or Jesus and the twelve disciples in the New Testament, or Martin Luther King,

Ralph Abernathy, Rosa Parks, Jo Ann Robinson and E D Nixon during the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

A leadership team offers a structured way to work together interdependently, each person taking leadership on

during part of the team’s activity. At their best leadership teams recognize and put to productive use the unique

talents of the individuals who make up the team.

Team structures also help create strategic capacity—the ability to strategize creatively together in ways that

produce more vibrant, engaging strategy than any individual could create alone. In the Obama campaign, the

field structure created multiple layers of leadership teams to engage people creatively and strategically at all

levels of the campaign. Each state had a state leadership team that coordinated regional leadership teams (of

Regional Directors and Organizers), which coordinated local neighborhood leadership teams of volunteer

leaders.

At every level the people on leadership teams had a clear mission with clear goals and the ability to strategize

creatively together about how to carry out their mission and meet their goals. This structure created multiple

points of entry for volunteers, and multiple opportunities to learn and to exercise leadership.

Leadership teams provide a foundation from which an organization can expand its reach. Once a team is formed,

systems can be created to establish a rhythm of regular meetings, clear decisions and visible accountability,

increasing the organization’s effectiveness. One person alone cannot organize 500 people. It is built by finding

people willing and able to commit to helping build it, and creating relationships and a solid structure from which

it can be built.

So why don’t people always work in teams?

We have all been part of volunteer teams that have not worked well. They fall into factions, they alienate each

other, or all the work falls on one person. Some aim to keep the pond small so they can feel like big fish. So many

of us come to the conclusion: I’ll just do it on my own; I hate meetings, just tell me what to do; I don’t want any

responsibility; just give me stamps to lick. There’s just one problem: we can’t become powerful enough to do

what we need to do if we can’t even work together to build campaigns we can take action on.

The challenge is to create conditions for our leadership teams that are more likely to generate successful

collaboration and strategic action. When groups of people come together, conflict is always present. Effective

teams are structured in a way to channel that conflict in productive ways, allowing the team to achieve the goals

it needs to win.

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

16

Three measures of an effective team:

1. OUTPUT (WORLD): The success of your team in taking the action required to achieve its valued goals –

winning the game, winning the campaign, putting on the play, etc.

2. CAPACITY (TEAM): Over time your team is learning how to work more effectively as a team, and

developing more leadership.

3. LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT (INDIVIDUAL): Individuals who participate on your team learn and grow

as a result of their participation.

Three conditions that make for a “real” team.

Your team is bounded. You can name the people on it; they don’t come and go, whoever shows up doesn’t have

the automatic right to participate in the team. Most highly effective teams have no more than 4 - 8 members.

Your team is stable. It meets regularly. It’s not a different, random group of people every time. Membership of

the team remains constant long enough that the team learns to work together better and better; each member

is fully committed to be on the team and commits consistent time and effort to it.

Your team is interdependent. As on an athletic team, a string quartet, or an airplane cabin crew, the contribution

that each person makes is critical to the success of the whole. Team members have a vital interest in each other’s

success, looking for ways to offer support.

Three steps to launching an effective team: purpose, ground rules, and roles.

You have a shared – and engaging –purpose. You are clear on what you have created your team to do (purpose),

who you will be doing it with (constituency), and what kinds of activities your team will participate in. The work

you have to do is readily understood, it’s challenging, it matters and you know why it matters. Team members

need to be able to articulate for themselves and others this "purpose".

You have created clear interdependent roles. Each team member must have their own responsibility, their own

“chunk” of the work, on which the success of the whole depends. No one is carrying out activity in a silo that’s

secretive to others. A good team will have a diversity of identities, experiences and opinions, ensuring that

everyone is bringing the most possible to the table.

Your team has explicit ground rules. Your team sets clear expectations for how to govern itself in your work

together. How will you manage meetings, regular communication, decisions, and commitments? And, most

importantly, how will you correct ground-rule violations so they remain real ground rules? Teams with explicit

operating rules are more likely to achieve their goals. Some team norms are operational, such as how often will

we meet? How will we share and store documents? Communicate with others outside the team? etc. Others

address expectations for member interaction with each other. Initial norms guide your team in its early stages as

members learn how to work together. Norms can be refined through regular group review of how well the team

is doing.

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

17

CREATING SHARED STRATEGY

When you structured your leadership team you decided on a shared purpose: your overall mission, your

constituency, and the kind of activities you’ll undertake. The challenge now is to strategize just HOW you will carry

out that purpose.

The first step is to identify the people whom you are organizing, your constituency, and map out the other relevant

actors. The second step is to come up with the goal of your organizing effort: what exactly is the problem is you

hope to solve, how would the world look different if it were solved, why hasn’t that problem been solved, what

would it take to solve it, and toward what clear, observable, and motivational goal could members of your

constituency focus their work to get started, build their capacity, and develop their leadership? The third step is

to figure out how your constituency could turn resources it has into the power it needs to achieve that goal: what

tactics could it use, how could they target their efforts, and how would they time their campaign.

Strategy is “turning resources you have into the power you need to get what you want - your goal.

• Strategic Goal (what you want): The goal is a clear, measurable point that allows you to know if you’ve won or

lost, and that meets the challenge your constituency faces.

• Power (what you need): tactics through which you can turn your resources into the capacity you need to

achieve your goal.

• Resources (what your constituency has): time, money, skills, relationships, etc.

How Strategy Works

Strategy is Motivated: What’s the problem?

We are natural strategists. We conceive purposes, encounter obstacles in achieving those purposes, and we

figure out how to overcomes those obstacles. But because we are also creatures of habit, we only strategize when

we have to: when we have a problem, something goes wrong, something forces a change in our plans. That’s

when we pay attention, take a look around, and decide we have to do something differently. Just as our emotional

understanding inhabits the stories we tell, our cognitive understanding inhabits the strategy we devise.

Strategy is Creative: What can we do about the problem?

Strategy requires developing an understanding of why the problem hasn’t been solved, as well as a theory of how

to solve it, a theory of change. Moreover because those who resist change often have access to more resources,

those who seek change often have to be more resourceful. We have to use this resourcefulness to create the

capacity – the power – to get the problem solved. It’s not so much about getting “more” resources as it is about

using one’s resources smartly and creatively.

Strategy is a Verb: How can we adapt as we learn to solve the problem?

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

18

The real action in strategy is, as Alinsky put it, in the reaction – by other actors, the opposition, and the challenges

and opportunities that emerge along the way. What makes it “strategy” and not “reaction” is the mindfulness we

can bring to bear on our choices relative to what we want to achieve, like a potter interacting with the clay on the

wheel, as Mintzberg describes it.

Although our goal may remain constant, strategizing requires ongoing adaptation of current action to new

information. Something worked better than we expected. Something did not work that we had expected. Things

change. Some people oppose us so we have to respond. Launching a campaign only begins the work of

strategizing. This is one reason your leadership team should include a full diversity of the skills, access to

information and interests needed to achieve your goal. We call this “strategic capacity.” So strategy is not a single

event, but an ongoing process continuing throughout the life of a project. We plan, we act, we evaluate the results

of our action, we plan some more, we act further, evaluate further, etc. We strategize, as we implement, not prior

to it.

Strategy is Situated: How can I connect the view in the valley with the view from the mountains?

Strategy unfolds within a specific context, the particularities of which really matter. One of the most challenging

aspects of strategizing is that it requires both a mastery of the details of the “arena” in which it is enacted and the

ability to go up to the top of the mountain and get a view of the whole. The power of imaginative strategizing can

only be realized when rooted within an understanding of the trees AND the forest. One way to create the “arena

of action” is by mapping the “actors” are that populate that arena.

KEY STRATEGIC QUESTIONS

1. Who are my PEOPLE?

2. What CHANGE do they seek? (Goal)

3. Where can they get the POWER? (Theory of Change)

4. Which TACTICS can they use?

5. What is their TIMELINE?

STEP ONE: WHO ARE MY PEOPLE?

Constituency

Constituents are people who have a need to organize, who can contribute leadership, can commit resources, and

can become a new source of power. It makes a big difference whether we think of people with whom we work as

constituents, clients, or customers. Constituents (from the Latin for “stand together”) associate on behalf of

common interests, commit resources to acting on those interests, and have a voice in deciding how to act. Clients

(from the Latin for “one who leans on another”) have an interest in services others provide, do not contribute

resources to a common effort, nor do they have a voice in decisions. Customers (a term derived from trade) have

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

19

an interest in goods or services that a seller can provide in exchange for resources in which he or she has an

interest. The organizers job is to turn a community – people who share common values or interests – into a

constituency – people who can act on behalf of those values or interests.

Leadership

Although your constituency is the focus of your work, your goal as an organizer is to draw upon leadership from

within that constituency – the people with whom you work to organize everyone else. Their work, like your own,

is to “accept responsibility for enabling others to achieve purpose in the face of uncertainty.” They facilitate the

work members of their constituency must do to achieve their shared goals, represent their constituency to others,

and are accountable to their constituency. Your work with these leaders is to enable them to learn the five

organizing practices you are learning: relationship building, story telling, structuring, strategizing, and action. By

developing their leadership you, as an organizer, not only can get to “get to scale.” You are also creating new

capacity for action – power – within your constituency. For the purpose of this exercise your group here is your

leadership team.

Opposition

In pursuing their interests, constituents may find themselves to be in conflict with interests of other individuals or

organizations. An employers’ interest in maximizing profit, for example, may conflict with an employees' interest

in earning a comfortable wage. A tobacco company's interests may conflict not only with those of anti-smoking

groups, but of the public in general. A street gang's interests may conflict with those of a church youth group.

The interests of a Republican Congressional candidate conflict with those of the Democratic candidate in the

same district. At times, however, opposition may not be immediately obvious, emerging clearly only in the course

of a campaign.

Supporters

People whose interests are not directly or obviously affected may find it to be in their interest to back an

organization’s work financially, politically, voluntarily, etc. Although they may not be part of the constituency, they

may sit on governing boards. For example, Church organizations and foundations provided a great deal of

support for the civil rights movement.

Competitors and Collaborators

These are individuals or organizations with which we may share some interests, but not others. They may target

the same constituency, the same sources of support, or face the same opposition. Two unions trying to organize

the same workforce may compete or collaborate. Two community groups trying to serve the same constituency

may compete or collaborate in their fundraising.

Other Actors

These are individuals and actors who may have a great deal of relevance to the problem at hand, but could

contribute to solving it, or making it harder to solve, in many different ways. This includes the media, the courts,

the general public, for example. Mapping the actors can help us identify those who may be responsible for the

problem our constituency faces, where they can find allies, and who else has an interest in the situation.

STEP TWO: WHAT CHANGE DO THEY SEEK: GOALS?

We then must decide on a strategic goal for our campaign by asking what exactly the problem is, how the world

might look if it were solved, why it hasn’t been solved, and what it would take to solve it.

What’s the problem?

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

20

What exactly is the problem, in real terms, in terms of people’s every day life?

Brainstorm your teams understanding of what the problem is with as much specificity as possible. Dig into it and

go beyond the accepted answers.

How would the world look different if the problem were solved?

What happens if we fail to act? What is the “nightmare” that awaits – or may already be here? On the other hand,

what could the world look like if we do act? What’s our realistic “dream”, a possibility that could become reality?

Why hasn’t the problem been solved?

If the world would look so much better for our people if the problem were solved, why hasn’t it been solved? Has

no one thought of it? Did people try, but found they were meeting too much resistance? Did people not know

how? Did they lack information? Did they lack technology? Would solving the problem threaten interests powerful

enough to derail the attempts?

What would it take to solve the problem?

More information? Greater awareness? New tools? Better organization? Better communication? More power?

What changes by what people would be required for the problem to be solved?

What’s the goal?

Toward what goal can we work that may not solve the whole problem, but that could get us well on the way: it

would make a real change, could build our capacity, could motivate others, could create a foundation for what

comes next. No one campaign can solve everything, but unless we can focus our efforts on a clear outcome we

risk wasting precious resources in ways that won’t move us towards our ultimate goal. Here are some criteria to

consider for a motivational, strategic organizing campaign goal—one that builds leadership and power:

1) Specific Focus: It’s concrete, measurable, and meaningful. If your constituents win, achieving this goal

will result in visible, significant change in their daily lives. This is the difference between “our goal is to

win reproductive justice” and “our goal is to ensure that every student has access to free, round the clock

contraception on our campus.” We make progress on the first one by turning it into something that can

be achieved by moving specific decision makers to reallocate resources in specific ways. Your

constituency will need this focus to move into action.

2) Motivational: It has the makings of a good story. The goal is rooted in values important to your

constituency, requires taking on a real challenge, and stretches your resources: It isn’t something you can

win tomorrow. Think David and Goliath.

3) Leverage: It makes the most of your constituency’s strengths, experience and resources, but is outside

the strengths, experience and resources of your opponent.

4) Builds Capacity: It requires developing leadership who can organize their own constituency to enhance

the power of your organization. It offers multiple local targets or points of entry and organization.

5) Contagious: it could be emulated by others pursuing similar goals.

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

21

This pyramid chart offers a way to think about where the

goal of your campaign can be nested within a larger

mission in scope or in scale. At every level, strategy requires

imagining an outcome, assessing resources available to

achieve that outcome, and, in light of the context, devising

a theory of change: how to turn those resources into the

power needed to achieve that outcome, a theory that is

enacted through tactics, timing, and targeting. In the bus

boycott, planning the initial meeting required strategizing

as much as figuring out how to sustain the campaign for the

long haul. It is likely different people are responsible for

different strategic scope at different levels of an

organization or for different time periods, but good

strategy is required at every level.

After agreeing upon criteria that make for a good strategic goal in your context, brainstorm again, generating as

many possible goals as you can. Then evaluate them each against the criteria you’ve established. Then come up

with an “if-then sentence”, imagining ways your constituents could use their resources to shift power in order to

achieve their goals.

STEP 3: WHERE CAN THEY GET THE POWER: THEORY OF CHANGE?

Figuring out how to achieve a strategic goal – or even what goal is worth trying to achieve - requires developing

a “theory of change? We all make assumptions about how change happens. Some people think that sharing

information widely enough (or “raise awareness”) about a problem will change things. Others contend that if we

just get all the “stakeholders” into the same room and talk with each others we’ll discover that we have more in

common than that separates us and that will solve the problem. Still others think we just need to be smarter about

figuring out the solution.

Community organizers focus on the community, their constituency, because they believe that unless the

community itself develops its own capacity to solve the problem, it won’t remain solved. Another word for

“capacity” is “power” or, as Dr. King defined it “the ability to achieve purpose.” Power grows out of the influence

that we can have on each other. If your interest in my resources is greater than my interest in your resources, I get

some power over you – so I can use your resources for my purposes. On the other hand, if we have an equal

interest in each other’s resources we can collaborate to create more power with each other to bring more capacity

to bear on achieving our purposes than we can alone. So the question is how to proactively organize our resources

to shift the power enough to win the change we want, building our capacity to win more over time? Since power

is a kind of relationship, tracking it down requires asking four questions:

• What do WE want?

• Who has the RESOURCES to create that change?

• What do THEY want?

• What resources do WE have that THEY want or need?

If it turns out that we have the resources we need, but just need to use them more collaboratively, then it’s a

“power with” dynamic. If it turns out that the resources we need have to come from somewhere else, then it’s a

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

22

“power over” dynamic. So the question is how our constituency can use its resources in ways that will create the

capacity it needs to achieve the goal. IF we do this, THEN that will likely happen. Test this out with a series of “If-

Then” sentences. Once your satisfied you are ready to articulate your organizing sentence:

“We are organizing WHO to achieve WHAT (goal) by HOW (theory of change) to achieve what CHANGE ”

STEP 4: WHAT TACTICS CAN THEY USE?

Remember what a “tactic” is? It’s the activity that makes your strategy real. Strategy without tactics is just a bunch

of ideas. Tactics without strategy wastes resources. So the art of organizing is in the dynamic relationship between

strategy and tactics, using the strategy to inform the tactics, and learning from the tactics to adapt strategy.

Your campaign will get into trouble if you use a tactic just because you happen to be familiar with it - but haven’t

figured out how that tactic can actually help you achieve your goal. Similarly, if you spend all your time strategizing,

without investing the time, effort, and skill to learn how to use the tactics you need skillfully, you waste your time.

Strategy is a way of hypothesizing: if I do this (tactic), then this (goal) may happen. And like any hypothesis the

proof is in the testing of it. Criteria for good tactics include:

• Strategic: it makes good use of your constituency’s resources to make concrete, measurable progress

toward campaign goals. Saul Alinsky and Gene Sharp are excellent sources of tactical ideas.

• Strengthens your organization: it improves the capacity of your people to work together.

• Supports leadership development: It develops new skills, new understanding, and, most importantly, new

leadership.

There are two ways to operate in the world—you can be reactive, as many organizations are, or you can be

proactive. In order to be proactive you have to set your own campaign goals and timeline, organizing your tactics

so that they build capacity and momentum over time.

STEP 5: WHAT IS THEIR TIMELINE?

The timing of a campaign is structured as an unfolding narrative or story. It begins with a foundation period

(prologue), starts crisply with a kick-off (curtain goes up), builds slowly to successive peaks (act one, act two),

culminates in a final peak determining the outcome (denouement), and is resolved as we celebrate the outcome

(epilogue). Our efforts generate momentum not mysteriously, but as a snowball. As we accomplish each objective

we generate new resources that can be applied to achieve the subsequent greater objective. Our motivation

grows as each small success persuades us that the subsequent success is achievable - and our commitment grows.

A campaign timeline has clear phases, with a peak at the end of each phase—a threshold moment when we have

succeed in creating a new capacity we can now put to work to achieving our next peak. For example, one phase

might be a 2 month fundraising and house meeting campaign that ends in a campaign kickoff meeting or rally.

Another phase might be 2 months of door-to-door contact with constituents affected by the problem you’re trying

to solve, collecting a target number of petitions to deliver with a march on the Mayor at City Hall at the end,

another peak. But within each phase there is a predictable cycle, which in a sense is a mini-campaign in itself:

training, launch, action, more action, peak, evaluation. When organizing a peak, keep in mind a specific outcome

that you want the peak to generate. For example, if you want to sign-up 50 new volunteers at an event or launch

three neighborhood teams, how do you make that happen?

!

Originally!adapted!from!the!works!of!Marshall!Ganz,!Harvard! University!

23

After each peak, your staff, volunteers and members need time to rest, learn, re-train and plan for the next phase.

Often organizations say, “We don’t have time for that!” Campaigns that don’t take time to reflect, adjust and re-

train end up burning through their human resources and becoming more and more reactionary over time.

Foundation

Kick-off!

goal

Peak!

goal

Strategic!goal

Evaluation!

&!next!steps

Peak!

goal

Capa city!!

(people,!skills,!etc.)

Time