A Report on the Food Education Learning Landscape

is report was only made possible due to the

generous funding received from the

AKO Foundation.

e AKO Foundation is a UK charity with a focus

on education and the arts founded by Nicolai

Tangen, the CEO and founder of the AKO Capital

LLP

List of tables/gures page 4

Foreword from Jamie Oliver, page 5

Executive Summary, page 6

1. Introduction, page 10

2. Context, page 14

2.1 What is the state of children’s health?, page 15

2.2 What is the current school food policy landscape?, page 15

2.3 Brief history of food education in schools in England, page 16

2.4 How is the food curriculum currently taught in the UK?, page 17

2.5 Who is being taught food education at school and college?, page 19

2.6 Routes to becoming a food teacher, page 20

2.7 Food teacher standards, page 20

2.8 Supporting food teachers with Continuing Professional Development (CPD), page 20

2.9 Where do teachers get lesson plans and resources?, page 21

3. Methodology, page 22

4. Findings, page 28

4.1 Introduction and overview, page 29

4.2 Overview of our ndings, page 30

4.3 Findings: Curriculum, page 31

4.4 Findings: Culture and Environment, page 44

4.5 Findings: Choices, page 53

4.6 Discussion, page 56

5. Recommendations, page 59

5.1 Ensure schools are healthy zones, page 60

5.2 Support the school workforce, page 64

5.3 Improve resources, page 67

5.4 Report back and evaluate, page 70

6. Case studies, page 74

7. Partner organisations, page 79

8. Endnotes, page 82

9. Bibliography, page 87

10. Acknowledgements, page 96

11. Appendices

11.1 SchoolZone Senior Leaders survey

11.2 Food Teachers Survey

11.3 Populus Parents survey

11.5 Supporting Literature

TABLE OF CONTENTS

4

• e current UK Cooking and Nutrition curriculum page 17

• Who is being taught food education at school and college? page 19

• Senior Leaders’ Sample Prole page 24

• School Teachers’ Sample Prole page 25

• Parent survey sample prole methodology and sample prole page 27

• COM-B model of behaviour change page 29

• Teacher reported average hours spent per school year on food education by Key Stage page 33

• Emphasis placed on dierent elements of the Cooking and nutrition curriculum page 33

• Parental satisfaction with food education in schools page 34

• Time as a barrier to delivering high quality food education page 39

• Budget as a barrier to delivering high quality food education page 40

• Facilities and resources as a barrier to delivering high quality food education page 40

• Sta training and experience as a barrier to delivering high quality food education page 41

• How would you rate the status of food, cooking and nutrition in your school? page 42 - 43

• How often is your school environment consistent with a positive whole school food ethos? page 45

• Monitoring and compliance with School Food Standards page 48

• Parental opinion on dierent aspects of school food policies page 49

• Foods high in salt, fat and sugar as part of fundraising page 50

• Foods high in salt, fat and sugar as part of school rewards page 51

• Foods high in salt, fat and sugar as part of school celebrations page 52

LIST OF TABLES/FIGURES

5

FOREWORD FROM JAMIE OLIVER

Childhood obesity has tripled over the past 30 years.

Food is no longer feeding us, it’s destroying us, and

it’s damaging our children’s health.

e biggest scandal is that childhood obesity

is avoidable. We all have the power to improve

the food our children eat and it starts with food

education.

I’ve been interested in school food and our kids’ food

education from day one. It’s been a personal journey

for me – from seeing rst-hand the shameful state of

school dinners back in 2005 to developing my own

food education programme, e Kitchen Garden

Project, and campaigning for better school food for a

decade.

is major report on food education, carried out

by my Foundation and helped by so many other

brilliant organisations, has studied all the data.

We’ve spoken to everyone, from headteachers to

food teachers, parents, school governors, and kids

themselves.

We’ve found that there’s a massive dierence

between the schools that are doing a great job

at delivering food education and those that are

struggling. We are alarmed at the concerns raised

about the food available, particularly in secondary

schools. But at the same time, we are really

motivated by the teachers, pupils and parents asking

for a healthier school environment.

We have a duty to make sure our kids understand

food. Where it comes from. Why it’s important.

How to cook it, and why it’s exciting. I want them to

grow up really loving food, so they can eat well, and

be healthy and happy.

Every passing year is a wasted opportunity to tackle

this problem head-on. Now that we have the hard

evidence to back up the changes we need to make –

let’s do it! It’s time to give our kids the support they

need for a healthy future.

is report lays out the really important, practical

recommendations that I hope government, school

leaders and others will put into action.

Jamie Oliver

6

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

“Every kid in every school no matter their background,

deserves to learn the basics about food - where it comes

from, how to cook it and how it aects their bodies. ese

life skills are as important as reading and writing, but

they’ve been lost over the past few generations. We need

to bring them back and bring up our kids to be street

wise about food.”

— Jamie Oliver

7

Why have we conducted a Food Education

Learning Landscape review?

What specically did we want to understand?

How did we conduct our research?

What did we nd out?

Cooking and Nutrition was introduced into the

English national curriculum for all 5-14 year olds

in 2014, but no study or evaluation has taken

place. e Jamie Oliver Food Foundation decided

to undertake a review to nd out how much food

education is going on in schools, and how eective

it is in helping our children develop key food skills

and a healthy attitude towards food. We wanted to

comment on current practice and unearth the pivotal

barriers to eective food education. We also wanted

to recommend actions to ensure our children can eat

better and improve their health and wellbeing.

To help us in our review, we worked in partnership

with the British Nutrition Foundation, the Food

Teachers Centre and the University of Sheeld, as

well as a large number of food education experts

who contributed time, expertise and resource in

gathering and analysing the data. We focused on

England, though used wider UK and international

data where relevant.

• What are pupils learning in their

food education?

• How are pupils learning? (i.e. who is

teaching; what kind of learning activities are

going on; what resources are available; where

are pupils learning; how does this vary across

school key stages?)

• How does the wider school food culture support

or hinder pupils healthy eating behaviours?

• What do pupils, parents, senior leaders and food

teachers think can raise the quality and

eectiveness of food education and food culture

in schools, to enable pupils to learn about, and

put into action, healthy eating behaviour?

We held a number of cross sector workshops

themed around ‘Curriculum’, ‘Whole School

Approach’ and ‘Behaviour Change’ to determine

what the focus of our research work should be.

We found a wide dierence between those

schools that were doing a great job at delivering

strong school food education, and those schools

that were struggling. We were alarmed at the

particular concerns raised about the school food

environment at secondary schools. Finally, the

pupil and parent voice was clear that they wanted

a healthier school environment.

We then commissioned:

• A two-part study with senior leaders in primary

and secondary schools (Schoolzone).

• A survey of food teachers in primary and

secondary schools (British Nutrition

Foundation and Food Teachers Centre).

• Focus groups with children and young people

(University of Sheeld).

• A survey of parents (Populus).

• Individual school visits and interviews,

including with school governors and school

caterers (Jamie Oliver Food Foundation).

We grouped our ndings into three themes:

e new national curriculum guidelines are

broadly being implemented, however, there is

great variation between schools in the quantity

(duration and frequency), content and quality of

food education.

Curriculum (formal food education)

• e development of pupils’ food knowledge

and skills is incomplete: delivery of all aspects

of the food curriculum is patchy, and many

children are unable to practice cooking skills.

• ere is limited evidence of pupils being taught

how to apply the principles of a healthy diet

in their food choices, e.g. learning about

decision-making and dealing with

social inuences.

• Food teachers report that they are heavily

constrained in their delivery of food education

by a lack of time, budget and facilities.

• Many children want more complexity and to

experience more hands-on learning.

• Food teachers and other teachers receive little

professional development in food education.

Executive Summary

8

So, what should be done?

e interaction of insucient food education and

the poor school food environment often leads

pupils to make choices that they acknowledge are

unhealthy, but often feel that they are compelled to

pursue. is is especially so at secondary level.

We were keen to ensure that all recommendations

address pupils’ ‘capability’ (their development of

knowledge and skills), ‘opportunity’ (their physical

and social food environment) and ‘motivation’

(their values and aspirations) so that they will be

better able to apply their food knowledge, including

making healthy choices.

Although some schools adopt a whole school

approach in which food education is linked to a

positive food culture and environment, this is still

not the norm, especially at secondary level.

Pupils in many schools, particularly secondary

schools, nd it dicult to make healthy choices

due to poor school food environments.

Culture (how a whole school approach supports

food education)

Choice (the food behaviours that children

are adopting)

• Most food provision at secondary level does not

support healthy eating behaviours. ere is

frequent provision of (often cheaper) unhealthy

foods throughout the school day, and children

noted a scarcity of healthy options.

• ere is often a lack of monitoring and

enforcement of School Food Standards at

secondary level.

• Pupils report that they can nd their food

dining environments noisy and unappealing,

especially at secondary level. Long queues limit

free time and they are sometimes unable to

obtain the food they want to eat.

• Pupils report a lack of positive messaging and

discourse about healthy eating and food choices

across their wider school environments.

• Unhealthy foods, like sweets, chocolate

and cakes, are commonly used as part of school

reward, celebration and fundraising activities.

is contradicts pupils’ food education and

parental opinion.

• Secondary pupils frequently reported choosing

to purchase and eat unhealthy foods, which are

oered through school catering facilities at

multiple points during the school day.

• Pupils described strong social and cultural

inuences on what, where and how they wanted

to eat. For example, secondary pupils often

favoured take away food.

• Secondary pupils also reported strong economic

inuences, particularly regarding the favourable

pricing of less healthy food and drink items,

over more healthy items.

• Pupils described how frequent fundraising

activities in primary and secondary school

encouraged them to purchase and eat

unhealthy foods.

Executive Summary

9

We have grouped our recommendations into four

areas:

Schools should be ‘healthy zones’ where pupil

health and wellbeing is consistently and actively

promoted through the policies and actions of the

whole school community.

Reporting and evaluation of food education, food

culture and food provision should be mandatory.

We must support the knowledge and skills

development of the whole school workforce to

enable quality food education delivery, supported

by a positive whole school approach to food.

Schools should be provided with the resources

to facilitate delivery of better, more consistent

food education.

Ensure schools are healthy zones

Report and evaluate

Support the school workforce

Improve resources

• Government should make School Food

Standards mandatory in all schools and cover

all food consumed when at school.

• e Department for Education (DfE) and

the National Governors Association should

jointly reissue guidance for governors on their

responsibilities for school food, and consider

placing a ‘health and wellbeing’ statutory duty

of care onto governors.

• An expert group should come together to work

up specic guidance for secondary schools in

developing a positive school food ethos

and culture.

• e Government’s proposed Healthy Rating

Scheme for schools should be a mandatory

requirement for all schools.

• e ve measures identied in the

Government’s School Food Plan must be

carried out.

• Ofsted reports should always report back

on ways the school is addressing pupil’s physical,

nutritional and emotional health and wellbeing.

• Ofsted should ensure that inspectors have the

appropriate skills and competence in health and

wellbeing to be able to assess appropriately.

• DfE should commission the development of a

suite of professional development courses to

support the delivery of eective food teaching

in schools.

• DfE should commission a set of headteacher

‘health and wellbeing core competencies’ linked to

wider standards for school leadership.

• A specic Initial Teacher Training ‘health and

wellbeing module’ should be included as part of

wider initial teacher training routes.

• DfE and the Department for Environment,

Food and Rural Aairs (Defra) should

establish an educational/industry working

group to make recommendations as to the

appropriate mix of academic and vocational

food qualications.

• Government should consider investing in

a cross departmental/cross sector food

initiative aimed at promotion of food

education in schools.

• A taskforce of food teachers, designers and

chefs should design and develop an aordable

‘cooking cube’ for those 75% of primary

schools that don’t have dedicated resources.

• e potential of a social investment loan

scheme for schools should be investigated.

• Government should ensure the Healthy Pupils

Capital Fund is both targeted to those schools

that need the most help and is dependent on

schools achieving the Healthy Rating Scheme.

Executive Summary

10

1. INTRODUCTION

“With rising obesity rates, the increase in fast foods and

the lack of food education, it has never been so important

for us all to understand how to eat healthily. is is even

more important in schools. Children must be supported,

nurtured, encouraged and taught to reach their full

potential. Children must learn how to eat healthily and

how to cook.”

— Tim Baker, headteacher of Charlton Manor

Primary School

11

ree years on from the introduction of Cooking and

Nutrition into the national curriculum (England),

there has been no study of its impact. We have no

national record of the amount or type of cooking

that is going on, how well it is being done, and the

skills being learnt. We have no understanding of

the condence and competence of our teachers in

delivering eective food education.

But, equally importantly, we don’t know how their

acquired skills and knowledge are being turned

into action. Will children want to cook well for

themselves (and their families) in the future, and

are the cooking knowledge and skills being taught

leading to behaviour change; are they making

healthier choices and eating well?

We cannot state the dierence food education makes

in tackling the multiple diet-related challenges our

children face. Although the food education learning

landscape is markedly more progressive than ever

before, there needs to be a comprehensive evaluation

into the gaps and barriers that still exist.

is is why the Jamie Oliver Food Foundation

decided to undertake a review to nd out how

much food education is going on in schools, and

how eective it is in helping our children develop

key food skills and a healthy attitude towards food.

We wanted to comment on current practice, unearth

the pivotal barriers to eective food education, and

recommend specic actions that can be taken so

that our children can eat better and improve their

health and wellbeing.

Over the last year, the Foundation has worked

with everyone who has a part to play. Working in

partnership with the British Nutrition Foundation,

the Food Teachers Centre (and with expert

academic contribution from e University of

Sheeld), we have talked to education and health

experts, teaching groups, non-governmental

organizations (NGOs), headteachers and food

teachers, governors and caterers, parents and pupils

to get a clear understanding of the current food

education learning landscape.

We have undertaken robust research using surveys,

interviews and focus groups, and read widely around

the existing reports and academic literature, in order

to uncover the exact nature of existing constraints

and propose responses and solutions to these

hurdles. rough this work, we aim to identify the

support and action needed to enable our schools

to deliver better food education and address the

multiple food-related challenges our children face.

12

1.1 WHY IS FOOD EDUCATION IMPORTANT?

“Instilling a love of cooking in pupils will also open a

door to one of the great expressions of human creativity.

Learning how to cook is a crucial life skill that enables

pupils to feed themselves and others aordably and well,

now and in later life.”

— National curriculum in England

13

Children’s food education is important. Not only

does it provide children with the skills, knowledge

and ability to lead healthy and happy lives, but

it gives children the opportunity to unlock

their imagination, understand the journey and

achievement of starting and nishing a recipe, and

to learn how to be self-sucient, responsible, and

informed. It also teaches important life skills, like

social awareness and manners, and can contribute

many levels to their development in terms of health

and nutrition, environmental awareness, and even

aect potential career choices. We have lost this

fundamental life skill and we are now in a climate

where we, more than ever, need to know to cook,

feed ourselves well, and lead long and healthy lives.

Food education is not only eective in isolation.

As part of a whole school approach, it is

complementary in leading to healthier outcomes,

higher attainment and improved behaviour and

concentration in the classroom. Public Health

England (PHE) have reported that a whole

school approach to healthy school meals, universally

implemented for all pupils, has shown improvements

in academic attainment at Key Stages 1 and 2,

especially for pupils with lower prior attainment

- the link between a healthy, balanced diet and

academic outcomes has been proven by numerous

academics and policy-makers.*

* See bibliography on page 87, and also “the library” webpage at www.schoolfoodplan.com/library

14

2. CONTEXT

“A survery undertaken in 2016 showed that only 16% of

millenials say they learnt to cook at school or college.” ²

15

2.1 What is the state of children’s health?

2.2 What is the current school food policy

landscape?

is is the rst generation of children likely to die

before their parents due to diet-related disease.

No child chooses to be overweight or obese and yet

by the time our children nish primary school one

in three are overweight or obese, with one in ve

children obese.¹¹

At the same time, children’s oral health is fast

declining. Rates of tooth decay are rising once again

and it is now the most common reason for hospital

admission for children aged 5 to 9 years old. As well

as untold misery for these children, they also miss an

average of three days o school.¹²

Eating disorders are also on the rise in young men

and women, experts cite increased social pressure on

body image¹³, not to mention fads and concerns of

dierent diets.

Because children spend 190 days per year at school,

schools have a profound inuence on the health and

habits of young people; research suggests the values,

ethos, and culture promoted in schools are critical

in this regard.¹¹ ey are an important place to

support embedding knowledge and practice of

healthy eating and healthy food choices.

In recent years, much has been made by

Government of the role schools can play in

tackling child obesity and shaping healthy

habits.¹ e publication of the School Food

Plan and the introduction of the PE and Sport

premium¹ in 2013 were important school

precursors to the further policy announcements

made in the 2016 Child Obesity Plan.¹

Several school-focused initiatives have been

implemented in recent years. Practical cooking and

nutrition lessons are now a mandatory part of the

national curriculum (England).¹ Revised School

Food Standards² are in place, designed to make it

easier for school cooks and caterers to serve tasty and

healthy meals. Following a Coalition announcement

in September 2013, universal infant free school

meals are now served daily to over 2.9m children.²¹

The current English government’s Child Obesity

Plan states it wants to build on these important

initiatives.²² The proposed Healthy Rating Scheme²³

for schools is planned to encourage them to

recognise and prioritise their roles in supporting

children to develop a healthy lifestyle. School Food

Standards are due a refresh to take account of

new, stricter, dietary guidelines aimed at reducing

sugar consumption.

Ofsted are tasked with taking the Healthy Rating

Scheme into account as an important source of

evidence about the steps taken by the school to

promote healthy eating and physical activity.

In addition, Ofsted have also been tasked with

undertaking a thematic review on obesity, healthy

eating and physical activity in schools, making future

recommendations on what more schools can do in

this area.

In February 2017, indications of how the £415m

Soft Drinks Industry Levy would be spent was

announced, (giving schools capital funding to

improve healthy eating and active lifestyles)²

though recent education spending decisions made

in July 2017 seem to have disappointingly removed

most of this healthy pupils capital fund.

However, a year on from the Child Obesity Plan’s

publication, no real action in schools has taken place,

with the only political discussion on school food

being the proposed Conservative manifesto pledge

to scrap universal infant free school meals and

replace them with universal free breakfasts.² Many

NGOs and campaign groups have been critical of

the lack of progress made by DfE.

16

2.3 Brief history of food education in schools

in England

Food teaching was introduced into schools in the

latter half of the nineteenth century in private and

secondary schools. Domestic economy (cookery,

needlework and laundry) was rst introduced into

the state school system (in pauper schools) in the

1840’s to help improve basic living standards. It

became compulsory for all girls in 1878, shortly

following the 1870 Education Act.

Since that time, food education and cooking has had

many iterations in schools, from Domestic Science,

Household Science, Housecraft, Home Economics,

through to the more recent Food Technology. It

continued to be a subject mainly for school girls,

and focused on the practical ‘instructional’ aspects

of cooking.

ere were no major developments to food teaching

until the national curriculum was introduced in

1990, where the aim was to prepare children for

the ‘opportunities, responsibilities and experiences

of adult life’. Food education was bound into the

new Technology (later revised to D&T) subject,

and moved away from just practical cooking into

teaching about food products and commercial food

technology.

e last two decades have seen an unstable journey

for food education on the curriculum. ere has

often been a lack of understanding and uncertainty

of the exact content of food technology, and no

common agreement of the syllabus or of how to

teach it. ere have also been multiple revisions to

the curriculum requirements over the years which

have provided constant challenges for teachers

attempting to understand what was required in

teaching food through D&T.

e Labour government set out plans to make food

a compulsory subject on the curriculum in 2007, and

also announced funding for food teaching with the

Licence to Cook programme, championed by then

DfE Secretary of State Ed Balls, giving all secondary

school pupils the opportunity to learn how to cook.

However, curriculum changes were stalled by the

Coalition government until 2014, when Cooking

and Nutrition was introduced. A new GCSE in

Cooking and Nutrition was introduced in September

2016. Food A Level was withdrawn from the

national curriculum from September 2017.

Tellingly, a survey undertaken in 2016 showed that

only 16% of millennials say they learnt to cook

at school or college, whereas 48% relied on their

parents to learn how to cook – an age that will

be dying out if the 16-34 year olds aren’t better

equipped with cooking skills for their future and

their children’s future.²

17

2.4 How is the food curriculum currently taught in

the UK?

Each of the UK’s four nations has its own school

curriculum. While there are dierences, key learning

around food is generally consistent.

England: Published in September 2014

In relation to food and nutrition education, Cooking

and Nutrition, a discrete strand within Design and

Technology for Key Stages 1 to 3, was introduced.

All maintained schools in England are required

to follow the curriculum, although they do have

the opportunity to enhance with additional

subject content.

Wales: Published in 2008

e curriculum starts at Key Stage 2 – (5-7 years is

covered by the early years phase). e curriculum is

statutory. Food education is taught via Design and

Technology. e Welsh Government is undertaking

a review of the curriculum², although this will not

be available in schools until September 2018 (and

used throughout Wales by September 2021).

Northern Ireland: Updated in 2014

Primary phase has no specic ‘food’ subject, but does

provide contexts in which work with food can be

undertaken. At Key Stage 3, Home Economics is

statutory. e curriculum is statutory.

Scotland: Published in 2010

Food education is from 3 to 16 years. Many subjects

support food education, which are cross-referenced,

e.g. Health and Wellbeing, Technologies, Science.

e curriculum is statutory.

18

e current English Cooking and Nutrition curriculum

As part of their work with food, pupils should be taught how to cook and apply the principles of nutrition

and healthy eating. Instilling a love of cooking in pupils will also open a door to one of the great expressions

of human creativity. Learning how to cook is a crucial life skill that enables pupils to feed themselves and

others aordably and well, now and in later life.

Pupils should be taught to:

Key stage 1

• Use the basic principles of a healthy and varied diet to prepare dishes

• Understand where food comes from

Key stage 2

• Understand and apply the principles of a healthy and varied diet

• Prepare and cook a variety of predominantly savoury dishes using a range of cooking techniques

• Understand seasonality, and know where and how a variety of ingredients are grown, reared, caught

and processed

Key stage 3

• Understand and apply the principles of nutrition and health

• Cook a repertoire of predominantly savoury dishes so that they are able to feed themselves and others a

healthy and varied diet

• Become competent in a range of cooking techniques [for example, selecting and preparing ingredients;

using utensils and electrical equipment; applying heat in dierent ways; using awareness of taste,

texture and smell to decide how to season dishes and combine ingredients; adapting and using their

own recipes]

• Understand the source, seasonality and characteristics of a broad range of ingredients

Food education is also taught through the subjects

of Science and Personal, Social, Health and

Economic (PSHE) education. In Science, the focus

is on understanding aspects of human nutrition and

digestion, whereas PSHE focuses on health

within a wider context of well being and making

food choices.

Other curriculum subjects can also contribute

through a cross-curricular approach, such as

Geography (where food grows), English

(following and writing recipes), Maths (weighing

and measuring), and History (how food choices

and consumption have changed over time). Physical

education plays an important role on physical

competency, and at Key Stage 3 healthy lifestyles

are introduced.

19

2.5 Who is being taught food education at school

and college?

We wanted to present an accurate picture of the

numbers of young people taking formal food

education qualications, but have found the exercise

challenging, despite engagement with professional

food education bodies. Both the British Nutrition

Foundation and the Food Teachers Centre fed

back that no one place brings together the full mix

of academic and vocational data sets around food

education. And it doesn’t seem that vocational data

for 14-19 year olds is separated out. Additionally,

food qualications are split across food production

(Agriculture and/or Horticulture) and the Catering

and Hospitality industries which means data sets

that are collected are further split.

Nonetheless, the following table attempts to

summarise the data sets we have received from

multiple sources. We have shown whether the study

is at school or college (sometimes it is a mixture of

both), and whether it is an academic or vocational

qualication. It seems that no data is collected on

those young people who might be studying food in

some form but are not taking a formal qualication.

For academic qualications there has been a marked

decline. In 2009/10, 93,795 food related GCSEs and

4,262 A or AS levels were awarded, this represents a

38% decrease in GCSE and 43% decrease in A level

from 2016 gures.

Figures, where available, are for 2016.

Year Groups Food related academic

qualications

Food related vocational

qualications

14-16 year olds 57,893 GCSE

(combination of Food Tech, Home

Economics and Catering GCSE’s)

5.5% of English pupils)

1,818 GCSE vocational

equivalent (taken at school)

16-19 year olds 2,416 Food A Level

(no A-level provision from 2017)

Agriculture, Horticulture and

Animal Care

34,900

(2,600 studying Agriculture

at Level 2 or 3)

Catering and Hospitality Approx:

35,000 cookery

6,500 food service

Formal Apprenticeships

(2017 data)

4,307

(in catering and hospitality)

20

2.6 Routes to becoming a food teacher

2.8 Supporting food teachers with Continuing

Professional Development (CPD)

In England, there are now many routes to acquiring

‘qualied teacher status’ (QTS). A useful table that

summarises this can be accessed from the House of

Commons Library.²

A primary school teacher will learn teaching skills

in order to teach a broad spectrum of subjects,

and there are generally no specialist routes

(except recently for Maths or PE). e Design &

Technology Association have reported that

most trainee primary teachers might receive

only three hours of D&T study (with food

being just one part).²

In secondary schools, trainee teachers study a

relevant course for what they will teach. However, in

relation to food they may have expertise in another

area of Design & Technology, such as resistant

materials or graphics, with food being a second

subject. Only a fth of secondary food teachers have

an A-level qualication in Food Technology.³

Food teacher numbers have declined in recent

years.³¹ In 2016, DfE reported there were only

4,500 food teachers across Key Stages 1, 2 and 3,

compared to 5,300 in 2011 (this compares to

34,100 English teachers in 2016). For the same

period for Key Stage 5 (Years 12 and 13) this

reduced further to 600.

In early 2015, PHE, the British Nutrition

Foundation, the Food Teachers Centre, OfSTED,

DfE and the School Food Plan met to discuss the

management and provision of food teaching and

to develop guidelines for food teaching, to support

rigour and set standards. e published guidelines

for primary and secondary schools³² set standards,

expectations and requirements for qualied food

teachers.

e intention was for the framework to be used to:

e framework recognises the importance of food

teachers supporting a whole school approach by

saying that accomplished food teachers ‘Use their

expertise to support the whole school approach to food

education and the provision and development of policies,

understanding and promoting the position of food

education in the health and wellbeing agenda of the

whole school’. ³³

CPD provision in schools was historically delivered

through local authorities, though funding cuts

have taken much of this away.³ Previous surveys

undertaken by the British Nutrition Foundation’s

research with primary school teachers in 2016

showed that only 3 in 10 of participating

teachers undertook any food related professional

development that year - and most of this was on

food safety. In order to further address this issue, the

British Nutrition Foundation launched an online

professional development training initiative for

teachers, entitled: Teaching food in primary schools: the

why, what and how.³

With no formal, centrally organised professional

support for food education, individual teachers and

schools take on the responsibility to interpret and

deliver the curriculum in their own way.

• Review and plan courses for trainee teachers,

and set out expectations for qualied

teacher status.

• Audit current practice by existing teachers,

supporting performance related development.

• Support professional reviews with colleagues.

• Plan and run professional training courses to

support best practice.

2.7 Food teacher standards

21

2.9 Where do teachers get lesson plans

and resources?

ere are a wealth of teaching resources and

support out there for schools to be able to deliver

cooking and food education. A search on the Times

Educational Supplement’s popular teaching resource

portal shows the wealth and scope of resources -

11,985 resources³ for ‘food education’. A search of

‘food’ gave an even greater 42,636 resources.³

Many teachers will devise their own lesson plans

and schemes of work. And there are multiple other

organisations who oer a variety of food education

resources. ese come in the shape of formal

curriculum and wider whole school approaches, from

cookery skills and recipes to food growing, farming

and the provenance of food. Such programmes and

organisations include the Children’s Food Trust’s

‘Let’s Get Cooking’, the Soil Association’s Food for Life

programme and the British Nutrition Foundation’s

Food - a fact of life.³ e Countryside Classroom³

portal also provides a place to access resources

from multiple organisations, focused on food,

farming and outdoor learning. And then there are

the many corporate school oers - voucher

schemes for cooking equipment, store or farm

visits and competitions.

e next section of this report lays out the

methodology used for collecting relevant data and

information to inform the current food education

learning landscape.

22

3. METHODOLOGY

“We brought together representatives from across the

food education sector to consider what questions we

should ask.”

23

At the outset of this review we brought together

representatives from across the food education sector

to consider what questions we should ask in order to

establish a baseline around:

Representatives worked in three groups (Curriculum,

Whole School Approach and Behaviour Change)

to determine what the focus of our research work

should be. ey identied the following questions:

Four key strands of work were commissioned in

order to answer these questions:

In addition, informal telephone interviews were

held with eight school governors and face to face

discussions took place between Jamie Oliver Food

Foundation sta and six school catering providers.

Working group members were involved in the

shaping of research design. Dr Caroline Hart at the

University of Sheeld acted as academic advisor to

all strands of work. All data collection took place

between June and August 2017.

• What pupils are learning in their food

education lessons following the introduction

of the new Cooking and Nutrition curriculum

three years ago.

• How pupils are learning (who is teaching,

what kinds of learning activities are going

on, what resources are available, where are

pupils learning, how does this vary across

key stages).

• How school food cultures support or hinder

healthy eating behaviours among pupils.

• We also wanted to nd out what pupils, parents,

senior leaders and food teachers think can raise

the quality of food education and food culture

in schools to enable pupils to learn about, and

put into action, healthy eating behaviour.

Curriculum

Behaviour Change

Whole School Approach

• How are schools interpreting and implementing

the Cooking and Nutrition part of

the curriculum?

• How many schools are meeting national

curriculum requirements?

• Is delivery aected by type of school or

location? If so, how?

• Who is delivering food education and how?

• How eective has the introduction of Cooking

and Nutrition in the national curriculum been

in terms of increasing the number of children

with adequate cooking skills and healthy

eating knowledge?

• Does delivery of national curriculum

requirements lead to behaviour change?

• How many schools have a whole school

approach to food education and what does this

look like?

• What food education is being taught formally

within the D&T Cooking and Nutrition

curriculum compared to the food education

within wider delivery of curriculum?

• What food education activities are taking place

in school, but outside of the formal curriculum?

How do these contribute to the delivery of

food culture?

• Are whole school approaches eective? If so,

why? If not, what can be done to change them?

How do we know what is eective?

• What will propel schools from an inclination

to have food education, to teaching it at school

and creating a whole school food culture?

• What are schools doing to aect behaviour/

attitudes with regard to:

• Food preparation?

• Food and drink choice?

• What are the dynamics of getting children to

eat and drink more healthily?

• Are food education frameworks eective to help

change behaviour? If so, why? If not, what can

be done to change them?

• Does a whole school approach to food

education enable behaviour change? If so, how?

• How can/do schools create the right

environment for behaviour change to happen?

• A two-part study with senior leaders in primary

and secondary schools.

• A survey of food teachers in primary and

secondary schools.

• Focus groups with children and young people.

• An omnibus survey of parents.

24

3.1 Senior leaders

Senior Leaders Sample Prole

Primary

Secondary

LA maintained schools

LA maintained schools

Respondents

Respondents

School Type

School Type

DfE Edubase database

DfE Edubase database

Academies

Academies

Other

Other

Previous reviews of food in school, such as the

School Food Plan and the Food Growing in Schools

Taskforce, have found that school leadership is vital

in achieving high quality food education supported

by a positive school food culture. is research

strand was intended to help establish a baseline of

food education delivery in schools in England and

to build our understanding of senior leadership

engagement in, and perspectives on, food education.

Specialist education market research organisation

Schoolzone undertook a two-phase survey of

senior leaders. Phase 1 of the study was designed

to explore the issues and inform the survey work of

Phase 2, as well as provide important commentary

on the quantitative ndings. 50 senior leaders and

heads of Design & Technology were briefed by

webinar and then took part in a written interview.

In Phase 2, Schoolzone recruited participants via

their research panel, data was gathered via an online

questionnaire designed by the Food Education

Learning Landscape Research and Steering groups,

and rened in partnership with Schoolzone.

242 primary and 442 secondary responses were

obtained. 40% of respondents were from local

authority maintained schools, 46% were from

academies, and the remaining 14% respondents

were from a mix of independent, special schools,

colleges, free schools etc.

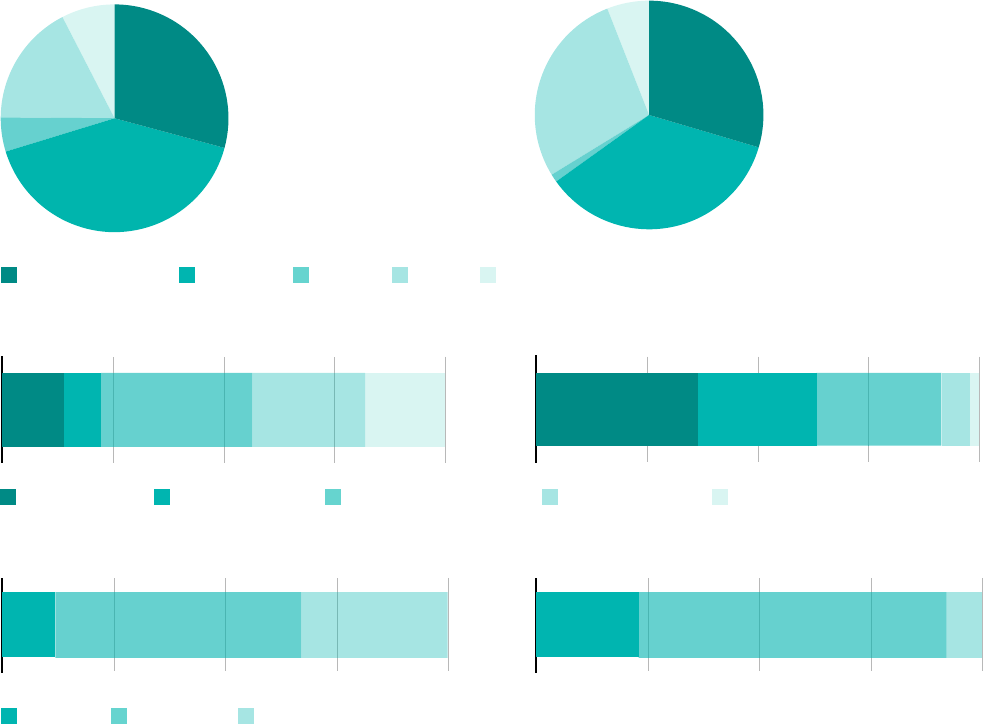

As can be seen from the statistical charts below, the

respondent prole obtained is representative of the

make-up of schools as dened by the Department

for Education’s Edubase database of all schools.

0%

17.5%

35%

52.5%

70%

64%

69%

28%

23%

8% 8%

500+

0%

300-499

100-299

<100

7%

12%

42%

50%

39%

30%

13%

8%

12.5% 25%

37.5% 50%

Respondents

Respondents

School Size

School Size

DfE Edubase database

DfE Edubase database

41-50%

>50%

31-40%

21-30%

<20%

0%

22.5% 45%

67.5% 90%

72%

78%

13%

17%

8%

6%

2%

2%

1%

1%

Respondents

Respondents

Percentage of pupils receiving Pupil Premium

Percentage of pupils receiving Pupil Premium

DfE Edubase database

DfE Edubase database

0%

17.5%

35%

52.5%

70%

27%

28%

55%

60%

12% 12%

1501+

1001-1500

500-1000

<500

16%

12%

35%

43%

36%

36%

13%

10%

0%

12.5% 25%

37.5% 50%

86%

79%

15%

9%

3%

5%

2%

1%

1%

0%

41-50%

>50%

31-40%

21-30%

<20%

0%

22.5% 45%

67.5% 90%

25

3.2 School food teachers survey

School food teachers are at the coalface of food

education, and as such have key insights on delivery

of the food curriculum. We hoped to gain from

them a detailed picture of what and how much

food education they are delivering and how this ts

with national curriculum guidance, as well as their

perspectives on the status of food education and

wider school food culture, including challenges to

high quality food education delivery. e British

Nutrition Foundation and Food Teachers Centre

designed an online survey, which was distributed via

their contact lists and through the wider networks

of organisations involved in the Food Education

Learning Landscape review.

A total of 1,075 secondary teachers responded,

this is nearly a quarter (24%) of all secondary food

teachers in publicly funded schools in England.¹

320 primary teacher responses were received, a lower

response rate for primary teachers was anticipated

as food is not taught as a specialist subject. For most

questions, a minimum of 750 secondary and 170

primary responses were completed.

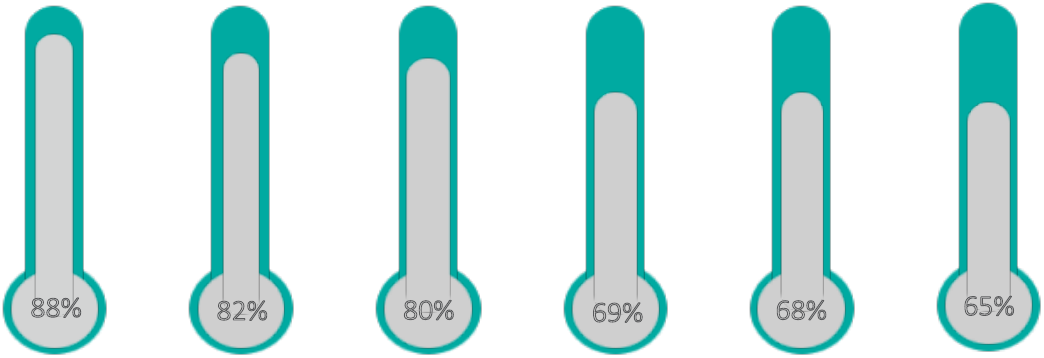

43% of primary school respondents identied

themselves as being from local authority maintained

schools and 21% were from academies. 50% of

primary school respondents were from schools

with between 100 and 400 pupils, 10% were from

schools with less than 100 pupils. 83% reported that

their school has a statutory obligation to follow the

national curriculum.

17% of secondary respondents were from local

authority maintained schools, 53% from academies.

70% were from schools with between 500 and 1,500

pupils, there were a similar number of respondents

with schools with less than and more than 500

pupils (13% and 17% respectively). 47% reported

that their school has a statutory obligation to follow

the national curriculum.

Around half of the sample were located in urban

areas, and 1/5 in rural areas. At primary level, 23%

were urban schools in a predominantly rural area, at

secondary this rose to 27%.

Respondents Respondents

Percentage of pupils

receiving Pupil Premium

Percentage of pupils

receiving Pupil Premium

DfE Edubase database DfE Edubase database

43%

69%

21%

23%

31%

8%

0%

17.5%

35%

52.5%

70%

Primary

School Teachers Sample Prole

LA maintained schools

Respondents

Respondents

School Type

School Type

DfE Edubase database

DfE Edubase database

Academies Other

500+

300-499

100-299

<100

11%

12%

38%

50%

36%

30%

15%

8%

0% 12.5% 25% 37.5% 50%

Respondents

Respondents

School Size

School Size

DfE Edubase database

DfE Edubase database

72%

78%

13%

17%

8%

6%

2%

2%

1%

1%

41-50%

>50%

31-40%

21-30%

<20%

0% 20% 40% 60% 80%

3%

2%

1%

1%

0%

41-50%

>50%

31-40%

21-30%

<20%

0% 22.5% 45% 67.5% 90%

86%

79%

9%

15%

5%

>1500

1001-1500

500-1000

<500

13%

12%

34%

43%

36%

36%

17%

10%

0% 12.5% 25% 37.5% 50%

21%

31%

0%

17.5%

35%

52.5%

70%

17%

28%

53%

12%

34%

60%

Secondary

26

3.3 Children and young people’s focus groups

is strand of work was conducted by an academic

team led by Dr Caroline Hart at the University

of Sheeld. We felt it was imperative to speak to

children and young people in order to understand

the impact of curriculum delivery and food

education as part of wider school food culture, as

well as to explore whether the interaction of these

two factors is leading to positive food behaviours.

e Jamie Oliver Food Foundation worked with

two local authorities with which it had existing

relationships to recruit schools. A sampling frame

was developed using three characteristics: percentage

of pupils receiving pupil premium; known level of

engagement with food education; and urban/rural

setting.

25 focus groups, took place over a period of one

month. 240 children and young people from 13

schools (7 primary schools and 6 secondary) took

part. Observations of the school food environment

and culture were also made and, where possible,

researchers spoke to teachers and headteachers.

Researchers used photographs, cooking utensils and

food items as stimuli for discussions around dierent

aspects of the food curriculum. Pupils took part in

participatory research activities, including drawing

and mapping exercises, which served as openings

for discussions of the wider school food education

environment and food culture. Pupils took the

researchers on school walks and took photographs

of locations in their school that prompted them to

think about food. Ethical approval for the research

was granted by the University of Sheeld. All

schools, pupils and their parents gave informed

voluntary consent for participation.

Parents are a critical part of any school community.

We wanted to understand how they view the

importance of food education and their experiences

of, and opinions on, school food culture. We were

particularly keen to know more about their views

on the use of food as part of rewards, fundraising

and celebration as this had emerged as a key theme

from the focus group work with children and

young people. We also wanted to understand more

about their appetite for engagement with schools

on school food education and culture. Survey

questions were designed by the Food Education

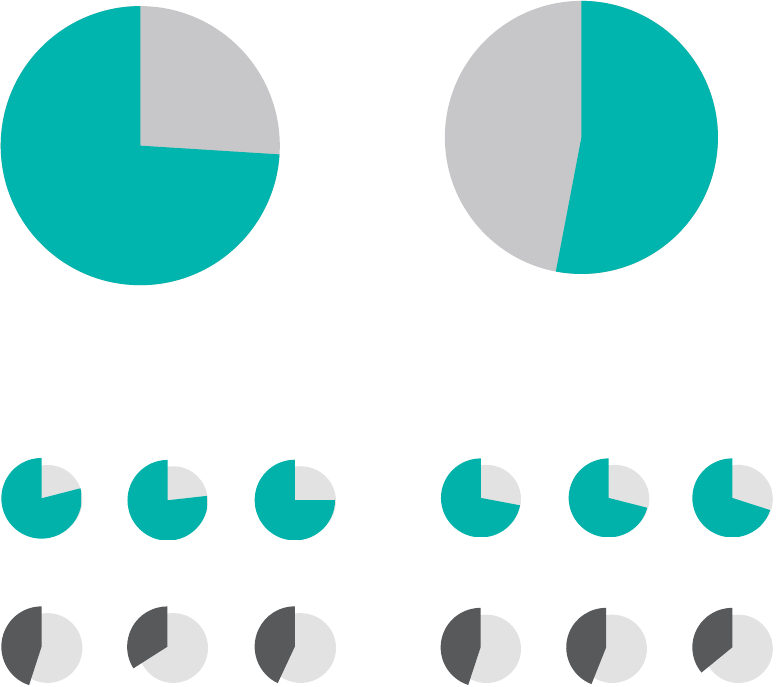

Learning Landscape review team. Specialist polling

organisation Populus interviewed a nationally

representative sample of 573 UK adults 18+ with

children aged 18 or under from its online panel.

Surveys were conducted across the country with

quotas set on age, gender and region. e results

were weighted to the prole of all adults using age,

gender, government oce region, social grade, taken

a foreign holiday in the last 3 years, tenure, number

of cars in the household and working status.

See opposite page for graphical representation.

Data from each of the strands was analysed by the

relevant commissioned organisations. e ndings

were then brought together using the framework of

Curriculum, Culture (the whole school approach to

food education) and Choice (the food behaviours

that children are adopting), additional sub themes

were developed iteratively as data was reviewed.

3.4 Parents’ survey

3.5 Analysis

27

Online omnibus

survey with the

general public

18-24%

AB 28%

11%

5%

11%

4%

8%

5%

8%

10%

9%

13%

11%

6%

25%

22%

24%

C1

C2

DE

25-34%

35-44%

45-54%

55-64%

65%+ 1%

6%

3%

31%

33%

35%

573 UK adults with

children aged 18

or under

2nd-3rd August

2017

Methodology

Gender

Region

Age

SEG

60% 40%

Sample Size

Fieldwork Dates

METHODOLOGY AND SAMPLE PROFILE

PARENT SURVEY SAMPLE PROFILE

28

4. FINDINGS

“How food education and school food culture currently

impact on pupils’ capability, opportunity and

motivation, and therefore food behaviours.”

29

4. 1 Introduction and overview

e School Food Plan (2013)² called for a whole

school food culture, recognising that neither

balanced school meals nor food education alone

were sucient to enable children to live well and

eat healthily. is focus on school culture and ethos

chimes well with Michie et al’s COM-B model

of key factors that shape behaviour.³ is model

describes how an individual requires the capability,

opportunity and motivation in order to adopt a

certain behaviour. In developing our surveys and

qualitative eldwork with pupils we also drew

on Amartya Sen’s capability approach which

highlights the importance not only of resources,

such as education and healthy food, but also of the

ability of individuals to ‘convert’ those resources

into ways of being they have reason to value. In the

context of this review, we were specically interested

in the freedom (capability) children have to choose

and eat healthy balanced diets, not only in terms of

their knowledge, and the availability of appropriate

food, but also in relation to social norms and

environment within the school that might encourage

or discourage healthy choices.

We have therefore explored the extent to which

the new national curriculum is enabling pupils

to have opportunities to develop key knowledge

and skills through their food education. We also

explored the relationship between what pupils are

learning in food education and whether they are able

to put their learning into practice in their school

environment. We wanted to know whether pupils’

wider school ethos and environment mirrored and

supported their food education.

COM-B MODEL OF BEHAVIOUR CHANGE*

Capability

Opportunity

Motivation

Behaviour

* Michie et al. Implementation Science 2011,http://www.implementationscience.com/content/6/1/42

30

4.2 Overview of our ndings

We found that the new national curriculum for

Cooking and Nutrition education contains many of

the vital ingredients needed to support pupils in

developing knowledge and skills to enable them to

prepare and cook healthy meals and to understand

what constitutes a healthy and balanced diet. In

particular, the new curriculum has led to pupils

participating in learning which has enabled them

to begin to develop knowledge and skills related to

food origins, food preparation and healthy eating.

is is a crucial rst step.

Some schools showed good practice, however

other schools have struggled to implement the new

curriculum. We also found that there are some key

elements missing, particularly related to opportunity

(physical and socio-cultural) and pupil motivation.

We then bring the ndings together in a discussion

section where we reect on how food education

and school food culture currently impact on pupils’

capability, opportunity and motivation, and therefore

food behaviours.

e ndings are presented in three core sections:

• e rst focuses on Curriculum and our rst

key issue related to developing pupils’

knowledge and skills in line with the new

national curriculum guidelines for KS1-3 on

Cooking and Nutrition.

• e second section turns to report ndings on

school food Culture in line with our interest in

the opportunities that schools are giving

children to practice healthy food behaviours.

• e third section oers ndings that illuminate

the Choices children are making in their

daily food practices in schools, helping us to

learn more about how we can work together to

further support pupils’ healthier food choices

and learning opportunities for cooking and

preparing balanced meals.

31

ere is strong support from parents and carers for

food education. Almost all (around 9 in 10) parents

and carers thought it was important that primary

and secondary pupils are taught about where food

comes from, how to apply learning about healthy

eating and nutrition, and practical cooking and food

preparation skills. We found some encouraging

examples of schools delivering comprehensive food

curricula that engage their pupils and succeed in

developing key knowledge and skills as set out in the

new national curriculum for Cooking and Nutrition.

However, the evidence from our comprehensive

review indicates that although signicant progress

has been made, there is still a long way to go, and

in many schools nationwide the picture of food

education gives cause for concern. is section of

the report considers how, and how far, dierent

elements of the curriculum are being implemented

and the reported challenges to delivering high

quality food education.

4.3 FINDINGS: CURRICULUM

‘Although signicant progress has been made, there is still

a long way to go and in many schools nationwide, the

picture of food education gives cause for concern.’

4.3.1 Introduction

32

Summary

e new national curriculum guidelines are broadly being implemented, however there is great variation

in the quantity (frequency and duration), content and quality of children and young people’s food learning

opportunities.

• Food education is not meeting pupils aspirations for their learning. Many report wanting more

complexity and challenge and opportunities for experiential learning

• e development of pupils’ food education knowledge is incomplete.

• Although most primary and secondary pupils are aware to some extent of the principles of healthy

eating, depth of knowledge varies considerably, and there is concern that each Key Stage repeats,

rather than builds on, prior learning.

• Knowledge about the origins of food is patchy at both primary and secondary level.

• Pupils also report that they would like to learn more about how to prepare complete meals and

cook on a budget.

• ere are limited opportunities for pupils to develop cooking and healthy eating skills.

• In some primary schools, practical cooking education experiences are poor. is is inhibiting pupils’

development of cooking and food preparation skills.

• ere is limited evidence of pupils being taught how to apply the principles of a healthy diet in their

daily food choices, e.g. learning about decision-making and how to deal with social inuences.

• Schools provide limited opportunities for pupils to learn about how to apply their knowledge

and skills. is is both within food education lessons and across the wider school environment.

• Food teachers report that they are heavily constrained in their delivery of food education by a lack of

training, time, budget and facilities.

• At primary level, more than half of pupils receive less than 10 hours a year and at secondary more

than three in ve schools deliver less than 20 hours a year. Many secondary school teachers report

that lesson time for food education has reduced over the last three years.

• Teachers report that they do not have the facilities such as cooking utensils and cookers they need,

nor the budget to replace broken items. ey also frequently report purchasing ingredients for

lessons with their own money as there is insucient budget available.

• Class size inhibits the teaching of cooking skills, such as knife skills and cooking with ovens.

• Only 1 in 4 primary teachers and just over half (52%) of secondary teachers reported that most sta

in their school had received CPD in food education in the last three years.

• Food education has a low status within many schools.

• Only 2 in 5 primary teachers felt the status of food education in their school was good or excellent

and 1 in 3 felt it was poor.

33

ere is signicant variation in the amount of time

pupils spend learning about food. Food teachers

told us that in more than half of primary schools,

pupils get less than 10 hours a year, but one in ten

get more than 30 hours. Time increases in secondary

4.3.2. Opportunities for learning about food and

nutrition are limited

provision, with half of teachers reporting that pupils

receive between 11 and 20 hours a year at Key Stage

3. However, between 11% and 16% of teachers

reported that pupils receive less than 10 hours

food education a year in Years 7-9.

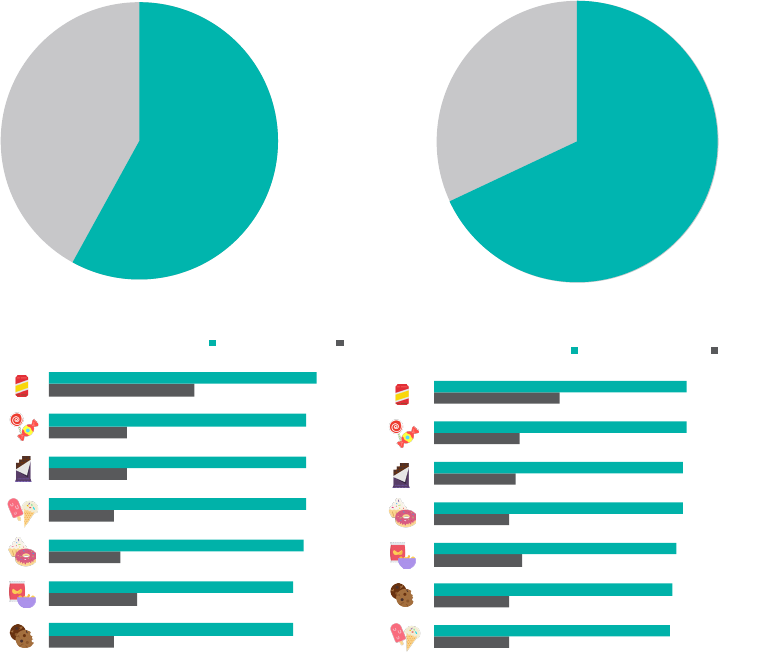

Key Stage 1 (n=186)

Key Stage 2 (n=186)

Key Stage 3 (n=799)

Less than 10

11-20

21-30

More than 30

53%

58%

14% 44% 24% 19%

28%

30% 8%

6%

9%

9%

Teacher reported average hours spent per school year on food education by Key Stage

Emphasis placed on dierent elements of the cooking and nutrition curriculum

Food choice

Healthy eating and nutrition

Practical skills and cooking techniques

Food origins

22%

19%

36%

86%

56%

77%

27%

25%

0%

25% 50%

75% 100%

Primary

Secondary

Percentage of teachers reporting they place a significant emphasis on curriculum area

34

4.3.3. National curriculum guidelines on Cooking

and Nutrition are being implemented. However,

inconsistency in delivery is a cause for concern

Net: Very/Fairly important & Net: Very/Fairly satised

Two out of three (65%) primary and 86% of

secondary teachers reported that they followed

national curriculum guidance on food education

which set out that pupils should learn about the

origins of food, cooking and preparation and the

principles of nutrition and a healthy diet. We found

that the national curriculum, guidelines on Cooking

and Nutrition are being implemented to a degree

in primary and secondary schools. In some primary

and secondary schools we visited, careful thought

had been given to the design and delivery of a

comprehensive curriculum. However, inconsistency

in food education across primary and secondary

schools is a cause for concern in terms of the

frequency of opportunities to learn about food and

nutrition, what pupils are learning and the quality

of pupil experiences.

Nearly all parents surveyed think it is important

that cooking and nutrition education are provided.

However, currently only 54% said that they were

satised with the education provided in their eldest

child’s school and 14% said they were dissatised.

A further 32% were either neutral or ambivalent in

their view of education provided.

Schools teach children about

where food comes from

Schools teach children how

to apply learning about

healthy eating and nutrition

Schools teach children

practical cooking and food

preparation skills

Satisfied Dissatisfied

Cookingandnutritioneducationprovided

92%

Primary

90%

Secondary

94%

Primary

94%

Secondary

83%

Primary

94%

Secondary

54%

14%

PARENTAL SATISFACTION WITH FOOD

EDUCATION IN SCHOOLS

35

4.3.4 Food origins 4.3.5 Food preparation and cooking

i) ere is signicant variation in the extent to which

pupils are learning about food origins.

Only about 1 in 5 teachers at primary said that

they placed a signicant emphasis on where food

comes from. is was reected in the ndings

from children and young people. Children in some

primary schools reported having learnt about food

provenance and seasonality in school, and were able

to talk condently about these issues. However, in

other schools, children did not recall learning on

these topics. In some schools, food origins had been

discussed as part of wider topics, such as history

or the environment. It was often when describing

food growing in a school garden or allotment and

visits to farms that pupils discussed seasonality and

provenance. ese experiences had excited them

and caused them to reect on issues such as animal

welfare, food miles and environmental impact. “You

could be horried by what happens or you could nd it

good that it’s local and free range, I nd it better because

if you see it, you know what happens and you are aware

of it.” (Year 6 pupil).

Only about 1 in 5 teachers at secondary level said

that they placed a signicant emphasis on where

food comes from. ere was also signicant variation

in what pupils could recollect learning about food

origins. Some were able to recall a good deal about

issues such as food miles, seasonality and animal

rearing and the production of meat and dairy foods,

while others recalled very little or no learning. ose

pupils that could remember particular lessons about

food origins and seasonality described learning

through worksheets, videos, independent computer

based research, presentations from their teacher and

mind mapping. All such learning at secondary level

had taken place as part of food technology lessons.

Depth of learning was best amongst those taking

GCSE Food and Nutrition.

i) Whilst most primary pupils have practiced a range

of cooking skills, others have barely prepared food

at all.

In many schools the frequency and duration of

opportunities to prepare and cook food are limited.

Only 1 in 3 primary school teachers said that they

placed a signicant emphasis on practical skills and

cooking techniques in their food teaching. Less than

half of primary school teachers told us that pupils

get the chance to practice food and cooking skills

more than twice a year.

Most primary pupils we spoke to were able to

recall having used a range of cooking utensils and

equipment to prepare a variety of sweet and savoury

dishes. In some schools we visited, cooking and

preparation were integrated across the curriculum

with frequent opportunities to make food (in some

as often as once a week). In these schools, children

described having used a range of techniques (peeling,

chopping, using sharp knives, grating, weighing,

working at a stove) and ingredients to cook a

number of sweet and savoury dishes, and described

these experiences with excitement. “It makes you feel

really satised, because when you see the end result it

might be what you expected, it might not but it’s just

really satisfying because you’ve created” (Year 6 pupil).

In some primary schools we visited pupils of all ages

struggled to recall opportunities to prepare food, and

where they had they had used very few techniques if

any. e quality of practical cooking experience for

some primary pupils was very poor. ey described

these experiences negatively, it “was quite boring

because I thought we was actually going to try and make

the dough, and maybe make the sauce, and chop up the

things, but we obviously didn’t. (Year 6 pupil).

36

4.3.6 Secondary school pupils report having

practiced a range of food preparation and

cooking techniques

4.3.7 e principles of a healthy diet and nutrition

At secondary level, there is a strong focus on

practical skills and techniques with 86% of food

teachers reporting that this had a signicant

emphasis in their food teaching. Many pupils

were able to describe a number of dishes they had

prepared and cooked in varying levels of depth.

Generally, they described these experiences with

enthusiasm. “It was like investigating, you was guring

out how to make stu and what you had to do, and it

was kind of like exciting, nding out how to do it and

you feel positive because you feel like you can do it again

and want to do it again.” (Year 7 pupil). Others felt

that food technology lessons were boring as they

were cooking dishes they had previously prepared

in primary school.

Some pupils described how the dishes they had

made had been new to them, both in terms of food

preparation and eating and a few said that they

had made them again at home. However, pupils

are generally not creating, or being oered, lasting

records or resources to enable them to recreate dishes

prepared in class on future occasions at home. For

example, very few pupils we spoke to had records of

the recipes they had used or notes on methods and

skills they had learned.

i) Although most pupils have learnt some basic

principles of nutrition and a healthy diet, depth of

knowledge varies considerably, and there is concern

that each Key Stage repeats, rather than builds on,

prior learning.

Although pupils at all ages were familiar with

the Eatwell Guide, it was not evident (with the

exception of some GCSE food technology students)

that at each Key Stage pupils were gaining an

enhanced knowledge or understanding of the

dierent nutritional properties of various foods or

their contribution to health and wellbeing as part of

a balanced diet.

56% of primary teachers said that they placed a

signicant emphasis on healthy eating and nutrition

theory. At primary level there was a stark contrast

between those pupils who had learnt a lot about the

principles of a healthy diet and those who had not.

In some schools, pupils were able to describe with

condence the principles of a healthy diet, name

dierent food groups and the foods within them

and, to a lesser extent, describe their contribution to

growth and wellbeing. In other schools, although

pupils understood the importance of a healthy diet,

they were often confused or lacked understanding of

what constitutes a healthy diet. In particular, they

felt that a balanced diet was one in which “Every

now and then you eat unhealthy so you have sugar in

you, so you won’t want to make yourself ill because you’ve

not got enough sugar in you” (Year 6 pupil). In one

school, Year 6 pupils conated a healthy diet with a

diet for weight loss.

77% of secondary teachers said that they placed

a signicant emphasis on healthy eating and

nutrition theory. Some pupils were able to recall

learning about food and healthy eating in PE or

Science lessons, or in form time, but this was rare

and generally not in depth. Food diaries had been

used in secondary schools as both a successful and

unsuccessful tool for learning about and applying the

principles of a healthy diet. In one school as part of

food technology, Year 7 pupils had kept a food diary

for a week and reviewed it against Eatwell Guide

recommendations: pupils had been supported by

their teacher to reect on their diet, and consider

what changes they could make to improve its

balance.

Pupils described the changes they had made as

a result “I wanted to eat more fruits, because there

wasn’t much in the fruit stu, but a lot of vegetables,

and I have started to have apples, and the other day

I had strawberries on bran akes.” (Year 7 boy). In a

contrasting experience in a dierent school, pupils

had reported their food intake during form time

for a week. ey described how there was limited

discussion of the data collected, “So they were trying

to keep track of our food, but then they wouldn’t explain

why our choices were bad, or why they were good, or why

we need to eat certain things, how it would help.(Year

10 pupil). is was certainly a missed opportunity.

37

4.3.8 Many pupils are not being given the

opportunity to learn about applying their

food learning

4.3.9 Experiential learning is a valuable part of

food education

Personal motivation to prepare, cook and eat healthy

food is vital to achieving healthy food practices

among children now and in the future. Most pupils

are not receiving learning opportunities to help them

to develop and reect on their values and aspirations

in relation to their food habits and cooking and

food preparation skills. Despite the high levels of

emphasis on healthy eating and nutrition theory

at both primary and secondary level, only 1 in 4

primary and secondary teachers said that they

place signicant emphasis in their food teaching

on food choice. However, in some primary schools,

children described how their teachers guided

their food choices, including as part of the daily

registration process.

It became clear that although secondary pupils were

able to describe the principles of a healthy diet, they

experienced challenges in applying this learning and

they struggled to navigate the often poor school

food environment to make healthy food choices.

“It’s harder to make healthy choices as well, cos there’s

hardly no fruit up there, nothing, no fruit or vegetables”

(Year 10 pupil).

With some exceptions, there was little evidence that

time had been spent discussing with pupils their

values and aspirations around food and health and

wellbeing in a way that would support them to make

healthy choices. Secondary pupils stated that they

rarely, if ever, have conversations with non-food

teaching sta about food choices.

Pupils of all ages remembered particularly clearly

what they had learnt through hands on experiences

such as food preparation and cooking and food

growing in school, as well as visits they had made

with school to farms, farmers markets, restaurants,

and supermarkets. ere is strong evidence in the

literature that experiential learning can support

learning outcomes. However, the frequency

of opportunities for food education through

experiential learning, particularly in terms of o-site

visits, varied considerably.

Some primary school children were able to recall

multiple o-site visits where they had learnt about

food, others were unable to recall any. ose that did

recall, described how they had contributed to their

learning “roughout being at this school it’s denitely