THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

New Driving Forces and Required Actions

International Food Policy Research Institute

Washington, D.C.

December 2007

Joachim von Braun

Copyright © 2007 International Food Policy Research Institute. All rights reserved. Sections of this report

may be reproduced for noncommercial and not-for-profit purposes without the express written permission of

but with acknowledgment to the International Food Policy Research Institute.

ISBN 10-digit: 0-89629-530-3

ISBN 13-digit: 978-0-89629-530-8

DOI: 10.2499/0896295303

Co

n

te

n

ts

Acknowledgments vi

The World Food Equation, Rewritten 1

Outlook on Global Food Scarcity and

Food-Energy Price Links 6

Poverty and the Food and Nutrition Situation 11

Conclusions 13

Notes 14

References 15

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

iii

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

iv

Tables

1. China: Per capita annual household consumption 2

2. Change in food-consumption quantity, ratios 2005/1990 2

3. Expected impacts of climate change on global cereal production 4

4. Consumption spending response (%) when prices change by 1%

(“elasticity”) 6

5. Changes in world prices of feedstock crops and sugar by 2020

under two scenarios compared with baseline levels (%) 9

6. Net cereal exports and imports for selected countries

(three-year averages 2003–2005) 10

7. Purchases and sales of staple foods by the poor

(% of total expenditure of all poor) 10

8. Expected number of undernourished in millions, incorporating

the effects of climate change 12

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

v

Figures

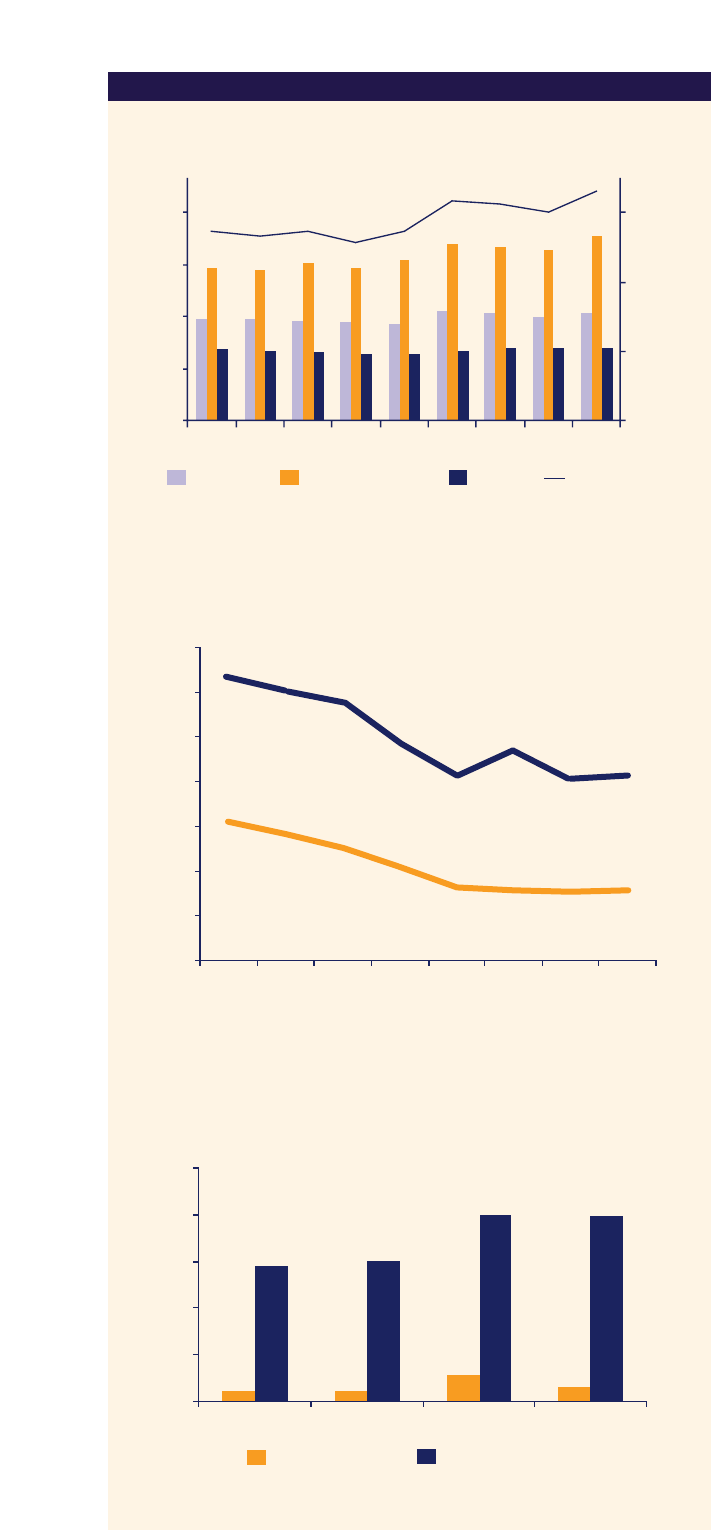

1.World cereal production, 2000–2007 (million tons) 3

2.World cereal stocks, 2000–2007 3

3. Annual growth rate of high-value agriculture production, 2004–2006 (percent) 3

4. A “corporate view” of the world food system: Sales of top 10 companies

(in billions of US dollars), 2004 and 2006 4

5. Global supply and demand for cereals, 2000 and 2006 5

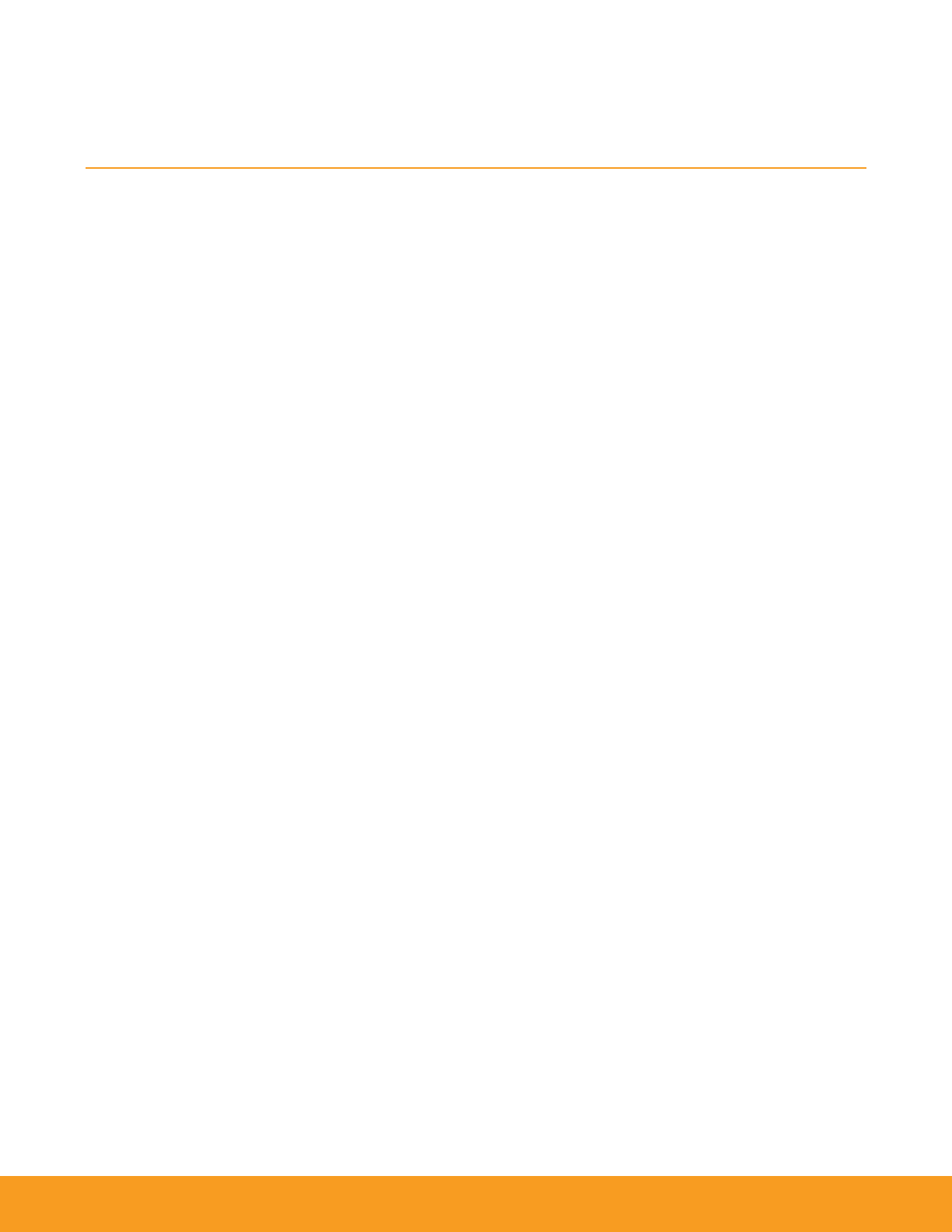

6. Commodity prices (US$/ton), January 2000–September 2007 6

7. Domestic and world prices of maize in Mexico (January 2004 = 100) 7

8. Producer and consumer prices of wheat in Ethiopia (2000 = 100) 7

9. Brazil: Ethanol and sugar prices, January 2000–September 2007 7

10. Meat and dairy prices (January 2000 = 100) 8

11. Calorie availability changes in 2020 compared to baseline (%) 8

12. Modeling the actual price change of cereals, 2000–2005

and scenario 2006–2015 (US$/ton) 10

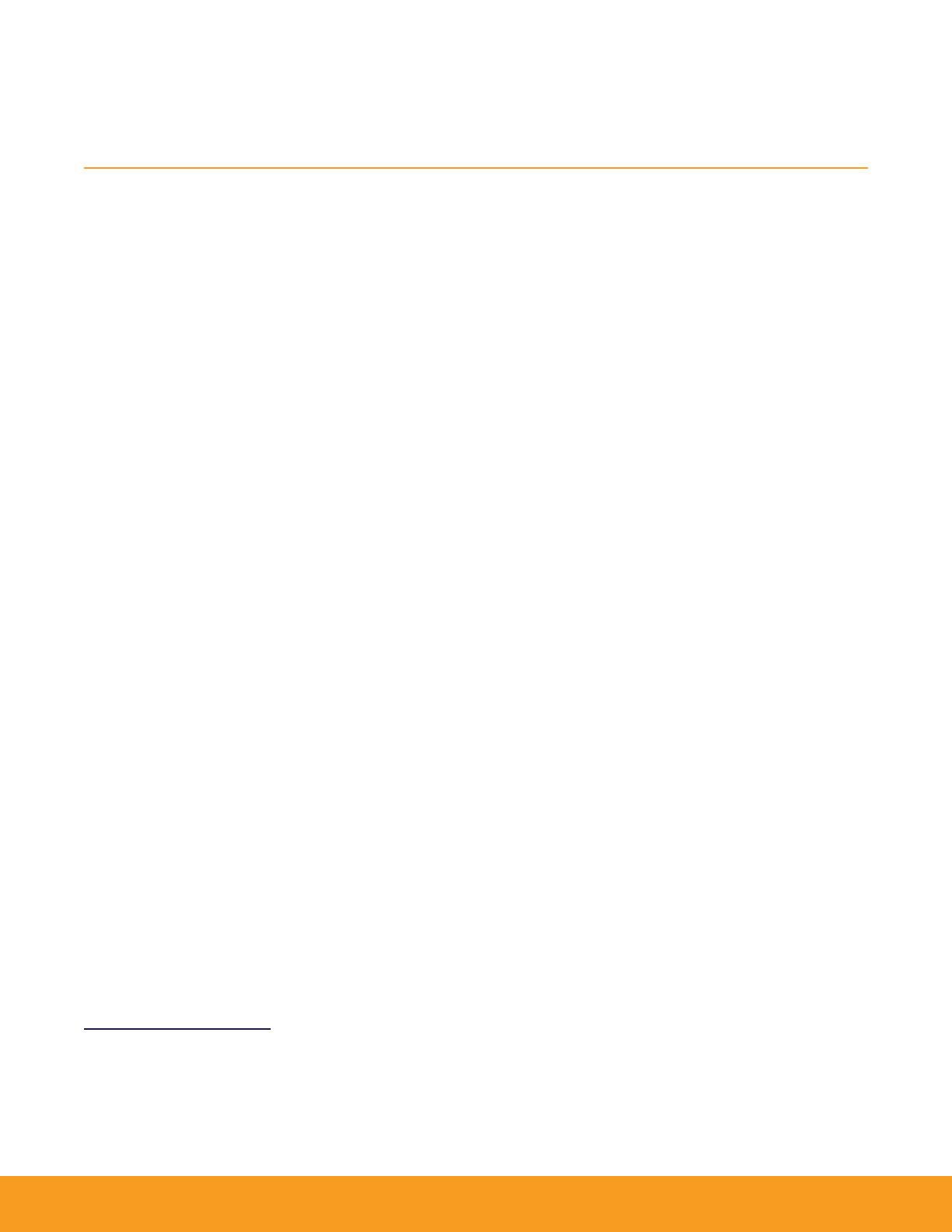

13. Prevalence of undernourishment in developing countries, 1992–2004

(% of population) 11

14. Changes in the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 12

15.Trends in the GHI and Gross National Income per capita

(1981, 1992, 1997, 2003) 12

Acknowledgments

T

he research cooperation and assistance for the development of this paper by Bella Nestorova,Tolulope Olofinbiyi,

Rajul Pandya-Lorch,Teunis van Rheenen, Mark Rosegrant, Siwa Msangi, and Klaus von Grebmer—all at IFPRI—is

gratefully acknowledged.

vi

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

1

T

he world food situation is currently being rapidly redefined by new driving forces. Income growth, cli-

mate change, high energy prices, globalization, and urbanization are transforming food consumption,

production, and markets.The influence of the private sector in the world food system, especially the leverage

of food retailers, is also rapidly increasing. Changes in food availability, rising commodity prices, and new pro-

ducer–consumer linkages have crucial implications for the livelihoods of poor and food-insecure people.

Analyzing and interpreting recent trends and emerging challenges in the world food situation is essential in

order to provide policymakers with the necessary information to mobilize adequate responses at the local,

national, regional, and international levels. It is also critical for helping to appropriately adjust research agendas

in agriculture, nutrition, and health. Not surprisingly, renewed global attention is being given to the role of agri-

culture and food in development policy, as can be seen from the World Bank’s World Development Report,

accelerated public action in African agriculture under the New Partnership for Africa’s Development

(NEPAD), and the Asian Development Bank’s recent initiatives for more investment in agriculture, to name

just a few examples.

The World Food Equation, Rewritten

Demand driven by high economic

growth and population change

Many parts of the developing world have experienced high

economic growth in recent years. Developing Asia, especially

China and India, continues to show strong sustained growth.

Real GDP in the region increased by 9 percent per annum

between 2004 and 2006. Sub-Saharan Africa also experi-

enced rapid economic growth of about 6 percent in the

same period. Even countries with high incidences and preva-

lences of hunger reported strong growth rates. Of the

world’s 34 most food-insecure countries,

1

22 had average

annual growth rates ranging from 5 to 16 percent between

2004 and 2006. Global economic growth, however, is pro-

jected to slow from 5.2 percent in 2007 to 4.8 percent in

2008 (IMF 2007a). Beyond 2008, world growth is expected

to remain in the 4 percent range while developing-country

growth is expected to average 6 percent (Mussa 2007).This

growth is a central force of change on the demand side of

the world food equation. High income growth in low-

income countries readily translates into increased consump-

tion of food, as will be further discussed below.

Another major force altering the food equation is shift-

ing rural–urban populations and the resulting impact on

spending and consumer preferences.The world’s urban pop-

ulation has grown more than the rural population; within

the next three decades, 61 percent of the world’s populace

is expected to live in urban areas (Cohen 2006). However,

three-quarters of the poor remain in rural areas, and rural

poverty will continue to be more prevalent than urban

poverty during the next several decades (Ravallion, Chen,

and Sangraula 2007).

Agricultural diversification toward high-value agricul-

tural production is a demand-driven process in which the

private sector plays a vital role (Gulati, Joshi, and Cummings

2007). Higher incomes, urbanization, and changing prefer-

ences are raising domestic consumer demand for high-value

products in developing countries.The composition of food

budgets is shifting from the consumption of grains and other

staple crops to vegetables, fruits, meat, dairy, and fish.The

demand for ready-to-cook and ready-to-eat foods is also

rising, particularly in urban areas. Consumers in Asia, espe-

cially in the cities, are also being exposed to nontraditional

foods. Due to diet globalization, the consumption of wheat

and wheat-based products, temperate-zone vegetables, and

dairy products in Asia has increased (Pingali 2006).

Today’s shifting patterns of consumption are expected

to be reinforced in the future.With an income growth of 5.5

percent per year in South Asia, annual per capita consump-

tion of rice in the region is projected to decline from its

2000 level by 4 percent by 2025. At the same time, con-

sumption of milk and vegetables is projected to increase by

70 percent and consumption of meat, eggs, and fish is pro-

jected to increase by 100 percent (Kumar et al. 2007).

In China, consumers in rural areas continue to be

more dependent on grains than consumers in urban areas

(Table 1). However, the increase in the consumption of

meat, fish and aquatic products, and fruits in rural areas is

even greater than in urban areas.

In India, cereal consumption remained unchanged

between 1990 and 2005, while consumption of oil crops

almost doubled; consumption of meat, milk, fish, fruits, and

vegetables also increased (Table 2). In other developing

countries, the shift to high-value demand has been less

obvious. In Brazil, Kenya, and Nigeria, the consumption of

some high-value products declined, which may be due to

growing inequality in some of these countries.

World food production and

stock developments

Wheat, coarse grains (including maize and sorghum), and

rice are staple foods for the majority of the world’s

population. Cereal supply depends on the production and

availability of stocks.World cereal production in 2006

was about 2 billion tons—2.4 percent less than in 2005

(Figure 1). Most of the decrease is the result of reduced

plantings and adverse weather in some major producing

and exporting countries. Between 2004 and 2006, wheat

and maize production in the European Union and the

United States decreased by 12 to 16 percent. On the

positive side, coarse grain production in China increased

by 12 percent and rice output in India increased by 9

percent (based on data from FAO 2006b and 2007b). In

2007, world cereal production is expected to rise by

almost 6 percent due to sharp increases in the

production of maize, the main coarse grain.

In 2006, global cereal stocks—especially wheat—

were at their lowest levels since the early 1980s. Stocks in

China, which constitute about 40 percent of total stocks,

declined significantly from 2000 to 2004 and have not

recovered in recent years (Figure 2). End-year cereal

stocks in 2007 are expected to remain at 2006 levels.

2

As opposed to cereals, the production of high-value

2

Table 1—China: Per capita annual household consumption

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

Urban Rural

1990 2006 2006/1990 1990 2006 2006/1990

Product (kg) (kg) ratio (kg) (kg) ratio

Grain 131 76 0.6 262 206 0.8

Pork, beef, and mutton 22 24 1.1 11 17 1.5

Poultry 3 8 2.4 1 4 2.8

Milk 5 18 4.0 1 3 2.9

Fish and aquatic products 8 13 1.7 2 5 2.4

Fruits 41 60 1.5 6 19 3.2

SOURCE: Data from National Bureau of Statistics of China 2007a and 2007b.

Table 2—Change in food-consumption quantity, ratios 2005/1990

Type India China Brazil Kenya Nigeria

Cereals 1.0 0.8 1.2 1.1 1.0

Oil crops 1.7 2.4 1.1 0.8 1.1

Meat 1.2 2.4 1.7 0.9 1.0

Milk 1.2 3.0 1.2 0.9 1.3

Fish 1.2 2.3 0.9 0.4 0.8

Fruits 1.3 3.5 0.8 1.0 1.1

Vegetables 1.3 2.9 1.3 1.0 1.3

SOURCE: Data from FAO 2007a.

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

3

agricultural commodities such as vegetables,

fruits, meat, and milk is growing at a fast rate

in developing countries (Figure 3).

Climate-change risks will have adverse

impacts on food production, compounding

the challenge of meeting global food demand.

Consequently, food import dependency is

projected to rise in many regions of the

developing world (IPCC 2007).With the

increased risk of droughts and floods due to

rising temperatures, crop-yield losses are

imminent. In more than 40 developing coun-

tries—mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa—cereal

yields are expected to decline, with mean

losses of about 15 percent by 2080 (Fischer

et al. 2005). Other estimates suggest that

although the aggregate impact on cereal pro-

duction between 1990 and 2080 might be

small—a decrease in production of less than

1 percent—large reductions of up to 22 per-

cent are likely in South Asia (Table 3). In con-

trast, developed countries and Latin America

are expected to experience absolute gains.

Impacts on the production of cereals also dif-

fer by crop type. Projections show that land

suitable for wheat production may almost

disappear in Africa. Nonetheless, global land

use due to climate change is estimated to

increase minimally by less than 1 percent. In

many parts of the developing world, espe-

cially in Africa, an expansion of arid lands of

up to 8 percent may be anticipated by 2080

(Fischer et al. 2005).

World agricultural GDP is projected to

decrease by 16 percent by 2020 due to global

warming. Again, the impact on developing

countries will be much more severe than on

developed countries. Output in developing

countries is projected to decline by 20 per-

cent, while output in industrial countries is

projected to decline by 6 percent (Cline

2007).

Carbon fertilization

3

could limit the

severity of climate-change effects to only 3

percent. However, technological change is not

expected to be able to alleviate output losses

and increase yields to a rate that would keep

up with growing food demand (Cline 2007).

Agricultural prices will thus also be affected

by climate variability and change.Temperature

increases of more than 3ºC may cause prices

to increase by up to 40 percent (Easterling et

al. 2007).

The riskier climate environment that is

expected will increase the demand for inno-

Million tons

Wheat Coarse grains Rice Total (right scale)

0

300

600

900

1,200

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Total million tons

800

1,200

1,600

2,000

Figure 1—World cereal production, 2000–2007 (million tons)

Source: Data from FAO 2003, 2005, 2006b, and 2007b.

Note: Data for 2007 are forecasts.

Million tons

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Figure 2—World cereal stocks, 2000–2007

Source: Data from FAO 2003, 2005, 2006b, and 2007b.

Note: Data for 2007 are forecasts.

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

Total stocks

China

Average production growth (%)

Vegetables Fruits Meat Milk

Figure 3—Annual growth rate of high-value agriculture production,

2004–2006 (percent)

Source: Data from FAO 2007a.

0.2 0.2

0.6

0.3

4.0

2.9

3.0

4.0

0

1

2

3

4

5

Developed countries Developing countries

vative insurance mechanisms, such as rainfall-indexed insur-

ance schemes that include regions and communities of small

farmers.This is an area for new institutional exploration.

Globalization and trade

A more open trade regime in agriculture would benefit

developing countries in general. Research by the

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) has

shown that the benefits of opening up and facilitating mar-

ket access between member countries of the Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and

developing countries—as well as among developing coun-

tries—would bring significant economic gains. However,

large advances in poverty reduction would not occur

except in some cases (Bouet et al. 2007). Multilateral discus-

sions toward further trade liberalization and the integration

of developing countries into the global economy are cur-

rently deadlocked.The conclusion of the World Trade

Organization (WTO) Doha Development Round has been

delayed due to divisions between developed and developing

countries and a lack of political commitment on the part of

key negotiating parties. In the area of agriculture, developed

countries have been unwilling to make major concessions.

The United States has been hesitant to decrease domestic

agricultural support in its new farm bill, while the European

Union has been hesitant to negotiate on its existing trade

restrictions on sensitive farm products. Deep divisions have

also emerged regarding the conditions for nonagricultural

market access proposed in Potsdam in July 2007.

In reaction to the lack of progress of the Doha Round,

many countries are increasingly engaging in regional and

bilateral trade agreements.The number of regional arrange-

ments reported to the WTO rose from 86 in 2000 to 159

in 2007 (UNCTAD 2007). Increasingly, South-South and

South-North regional initiatives have emerged—such as the

Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) between

the United States and Central America and the negotiations

between the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) states

and the European Union—and they may create more

opportunities for cooperation among developing countries

and for opening up their markets.

Another development has been the improvement of

the terms of trade for commodity exporters as a result of

increases in global prices.The share of developing countries

in global exports increased from 32 percent in 2000 to

37 percent in 2006, but there are large regional disparities.

Africa’s share in global exports, for example, increased only

from 2.3 to 2.8 percent in the same period (UNCTAD

2007).

Changes in the corporate food system

The growing power and leverage of international corpora-

tions are transforming the opportunities available to small

agricultural producers in developing countries.While new

prospects have arisen for some farmers, many

others have not been able to take advantage

of the new income-generating opportunities

since the rigorous safety and quality stan-

dards of food processors and food retailers

create high barriers to their market entry.

Transactions along the corporate food

chain have increased in the past two years.

Between 2004 and 2006, total global food

spending grew by 16 percent, from US$5.5

trillion to 6.4 trillion (Planet Retail 2007a). In

the same period, the sales of food retailers

increased by a disproportionately large

amount compared to the sales of food

processors and of companies in the food

input industry (Figure 4).The sales of the top

food processors and traders grew by 13 per-

cent, and the sales of the top 10 companies

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

4

Table 3—Expected impacts of climate

change on global cereal production

1990–2080

Region (% change)

World –0.6 to –0.9

Developed countries 2.7 to 9.0

Developing countries –3.3 to –7.2

Southeast Asia –2.5 to –7.8

South Asia –18.2 to –22.1

Sub-Saharan Africa –3.9 to –7.5

Latin America 5.2 to 12.5

SOURCE: Adapted from Tubiello and Fischer 2007.

2004 2006

Agricultural

input industry

Food processors

and traders

Food retailers

37

40

363

777

409

1,091

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

5

producing agricultural inputs (agrochemicals,

seeds, and traits) increased by 8 percent.The

sales of the top food retailers, however,

soared by more than 40 percent.While

supermarkets account for a large share of

retail sales in most developed and many

developing countries, independent grocers

continue to represent 85 percent of retail

sales in Vietnam and 77 percent in India

(Euromonitor 2007).

The process of horizontal consolidation

in the agricultural-input industry continues

on a global scale.The three leading agro-

chemical companies—Bayer Crop Science,

Syngenta, and BASF—account for roughly half

of the total market (UNCTAD 2006). In con-

trast, the top five retailers do not capture

more than a 13-percent share of the market.

Global data, however, mask substantial differ-

ences between countries; while the top five

retailers account for 57 percent of grocery

sales in Venezuela, they represent less than

4 percent of sales in Indonesia (Euromonitor

2007).Vertical integration of the food supply chain

increases the synergies between agricultural inputs, pro-

cessing, and retail, but overall competition within the dif-

ferent segments of the world food chain remains strong.

The changing supply-and-demand

framework of the food equation

The above-mentioned changes on the supply and demand

side of the world food equation have led to imbalances

and drastic price changes. Between 2000 and 2006, world

demand for cereals increased by 8 percent while cereal

prices increased by about 50 percent (Figure 5).

Thereafter, prices more than doubled by early 2008 (com-

pared to 2000). Supply is very inelastic, which means that it

does not respond quickly to price changes.Typically, aggre-

gate agriculture supply increases by 1 to 2 percent when

prices increase by 10 percent.That supply response

decreases further when farm prices are more volatile, but

increases as the result of improved infrastructure and

access to technology and rural finance.

The consumption of cereals has been consistently

higher than production in recent years and that has

reduced stocks. A breakdown of cereal demand by type of

use gives insights into the factors that have contributed to

the greater increase in consumption.While cereal use for

food and feed increased by 4 and 7 percent since 2000,

respectively, the use of cereals for industrial purposes—

such as biofuel production—increased by more than

25 percent (FAO 2003 and 2007b). In the United States

alone, the use of corn for ethanol production increased by

two and a half times between 2000 and 2006 (Earth Policy

Institute 2007).

Supply and demand changes do not fully explain the

price increases. Financial investors are becoming increas-

ingly interested in rising commodity prices, and speculative

transactions are adding to increased commodity-price

volatility. In 2006, the volume of traded global agricultural

futures and options rose by almost 30 percent.

Commodity exchanges can help to make food markets

more transparent and efficient.They are becoming more

relevant in India and China, and African countries are initi-

ating commodity exchanges as well, as has occurred in

Ethiopia, for example (Gabre-Madhin 2006).

Figure 5—Global supply and demand for cereals, 2000 and 2006

Source: Data from FAO 2003, 2005, 2006b, 2007b, and 2007c.

Notes: Supply and demand of cereals refer to the production and consumption of wheat,

coarse grains, and rice.

153

100

1,917 2,070

P

(2000=100)

D

2006

S

2006

D

2000

S

2000

Q

million tons

Due to government price

policies, trade restrictions, and

transportation costs, changes in

world commodity prices do not

automatically translate into

changes in domestic prices. In the

case of Mexico, the margin

between domestic and world

prices for maize has ranged

between 0 and 35 percent since

the beginning of 2004, and a

strong relationship between

domestic and world prices is evi-

dent (Figure 7). In India, the dif-

ferences between domestic and

international rice prices were

greater, averaging more than 100

percent between 2000 and

2006.

4

While domestic price-

stabilization policies diminish

price volatility, they require fiscal

resources and cause additional

market imperfections. Govern-

ment policies also change the

relationship between consumer and producer prices. For

instance, producer prices of wheat in Ethiopia increased

more than consumer prices from 2000 to 2006 (Figure 8).

Though international price changes do not fully trans-

late into equivalent domestic farm and consumer price

changes because of the different policies and trade positions

adopted by each country, they are in fact transmitted to

consumers and producers to a considerable extent.

The prices of commodities used in biofuel production

are becoming increasingly linked with energy prices. In

Brazil, which has been a pioneer in ethanol production since

the 1970s, the price of sugar is very closely connected to

the price of ethanol (Figure 9). A worrisome implication of

the increasing link between energy and food prices is that

high energy-price fluctuations are increasingly translated

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

6

Outlook on Global Food Scarcity and

Food-Energy Price Links

Cereal and energy price increases

W

orld cereal and energy prices are becoming increasingly linked. Since 2000, the prices of wheat

and petroleum have tripled, while the prices of corn and rice have almost doubled (Figure 6).

The impact of cereal price increases on food-insecure and poor households is already quite dramatic.

For every 1-percent increase in the price of food, food consumption expenditure in developing countries

decreases by 0.75 percent (Regmi et al. 2001). Faced with higher prices, the poor switch to foods that have

lower nutritional value and lack important micronutrients.

Figure 6—Commodity prices (US$/ton), Januar y 2000–September 2007

Jan-00

Jul-00

Jan-01

Jul-01

Jan-02

Jul-02

Jan-03

Jul-03

Jan-04

Jul-04

Jan-05

Jul-05

Jan-06

Jul-06

Jan-07

Jul-07

Source: Data from FAO 2007c and IMF 2007b; in current US $.

Commodity prices (US$/ton)

Oil

0

300

400

200

100

0

20

40

60

80

Wheat

Corn

Rice

Oil (right scale)

Table 4—Consumption spending response (%)

when prices change by 1% (“elasticity”)

Low-income High-income

countries countries

Food -0.59 -0.27

Bread and cereals -0.43 -0.14

Meat -0.63 -0.29

Dairy -0.70 -0.31

Fruit and vegetables -0.51 -0.23

SOURCE: Seale, Regmi, and Bernstein 2003.

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

7

Figure 5—Global supply and demand for cereals, 2000 and 2006

Source: Data from FAO 2003, 2005, 2006b, 2007b, and 2007c.

Notes: Supply and demand of cereals refer to the production and consumption of wheat,

coarse grains, and rice.

153

100

1,917 2,070

P

(2000=100)

D

2006

S

2006

D

2000

S

2000

Q

million tons

2004 2006

Agricultural

input industry

Food processors

and traders

Food retailers

37

40

363

777

409

1,091

Figure 8—Producer and consumer prices of wheat in Ethiopia

(2000 = 100)

Jan-00

Jul-00

Sources: Data from Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia 2007 and Ethiopian Grain

Trade Enterprise 2007.

Note: Consumer prices represent wholesale prices in Addis Ababa, and producer prices

are national farmgate prices.

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

Wheat producer

Wheat consumer

(2000 = 100)

Jan-01

Jul-01

Jan-02

Jul-02

Jan-03

Jul-03

Jan-04

Jul-04

Jan-05

Jul-05

Jan-06

Jul-06

Figure 7—Domestic and world prices of maize in Mexico

(January 2004 = 100)

Jan-04

May-04

Sep-04

Jan-05

May-05

Sep-05

Jan-06

May-06

Sep-06

Sep-07

Jan-07

May-07

Source: Data from Bank of Mexico 2007 and FAO 2007c.

Note: Domestic prices represent producer prices for the national market in Mexico.

(Jan. 2004 = 100)

60

80

100

120

140

160

Mexico maize

World maize

Figure 9—Brazil: Ethanol and sugar prices, January 2000–September 2007

Jan-00

Jul-00

Sources: Data from CEPEA 2007.

Notes: Fuel ethanol prices in Brazil refer to averages for the São Paulo market (mills,

distilleries, distributors, intermediaries). Hydrous ethanol is used as a substitute for gasoline

and Anhydrous ethanol is mixed with gasoline.

Anhydrous ethanol

Sugar (right scale)

US$/litre

Jan-01

Jul-01

Jan-02

Jul-02

Jan-03

Jul-03

Jan-04

Jul-04

Jan-05

Jul-05

Jan-06

Jul-06

Hydrated ethanol

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

0

0.04

0.08

0.12

0.16

US$/pound

Jan-07

Jul-07

into high food-price fluctuations. In the past five

years, price variations in oilseeds and in wheat

and corn have increased to about twice the lev-

els of previous decades.

5

The increasing demand for high-value com-

modities has resulted in surging prices for meat

and dairy products (Figure 10), and this is driv-

ing feed prices upward, too. Since the beginning

of 2000, butter and milk prices have tripled and

poultry prices have almost doubled.

The effects of price increase on consump-

tion are different across different countries and

consumer groups. Consumers in low-income

countries are much more responsive to price

changes than consumers in high-income coun-

tries (Table 4). Also, the demand for meat,

dairy, fruits, and vegetables is much more sensi-

tive to price, especially among the poor, than is

the demand for bread and cereals.

Scenario analyses of the

determinants of prices and

consumption

The effect of biofuels

When oil prices range between US$60 and $70

a barrel, biofuels are competitive with petro-

leum in many countries, even with existing

technologies. Efficiency benchmarks vary for

different biofuels, however, and ultimately, pro-

duction should be established and expanded

where comparative advantages exist.With oil

prices above US$90, the competitiveness is of

course even stronger.

Feedstock represents the principal share

of total biofuel production costs. For ethanol

and biodiesel, feedstock accounts for 50–70

percent and 70–80 percent of overall costs,

respectively (IEA 2004). Net production

costs—which are all costs related to produc-

tion, including investments—differ widely across

countries. For instance, Brazil produces ethanol

at about half the cost of Australia and one-third

the cost of Germany (Henniges 2005).

Significant increases in feedstock costs (by at

least 50 percent) in the past few years impinge

on comparative advantage and competitiveness.

The implication is that while the biofuel sector

will contribute to feedstock price changes, it

will also be a victim of these price changes.

Food-price projections have not yet been

able to fully take into account the impact of bio-

fuels expansion.When assessing potential devel-

opments in the biofuels sector and their

consequences, the OECD-FAO outlook makes

assumptions for a number of countries, including

the United States, the European Union, Canada,

and China. New biofuel technologies and policies

are viewed as uncertainties that

could dramatically impact future

food prices (OECD-FAO 2007).

The Food and Agricultural Policy

Research Institute (FAPRI) con-

ducts a detailed analysis of the

potential impact of policy on bio-

fuels and links between the

ethanol and gasoline markets, but

its extensive modeling is limited

to the United States.

A new, more comprehensive

global scenario analysis using

IFPRI’s International Model for

Policy Analysis of Agricultural

Commodities and Trade

(IMPACT) examines current

price effects and estimates future

ones. In view of the dynamic

world food situation and the rap-

idly changing biofuels sector,

IFPRI continuously updates and

refines its related models, so the

results presented here should be

viewed as work in progress.

Recently, the IMPACT model has

incorporated 2005/06 develop-

ments in supply and demand, and has generated two future

scenarios based on these developments:

• Scenario 1 is based on the actual biofuel investment

plans of many countries that have such plans and

assumes biofuel expansions for identified high-

potential countries that have not specified their plans.

• Scenario 2 assumes a more drastic

expansion of biofuels to double the

levels used in Scenario 1.

Under the planned biofuel expansion sce-

nario (Scenario 1), international prices increase

by 26 percent for maize and by 18 percent for

oilseeds. Under the more drastic biofuel expan-

sion scenario (Scenario 2), maize prices rise by

72 percent and oilseeds by 44 percent (Table 5).

Under both scenarios, the increase in crop

prices resulting from expanded biofuel produc-

tion is also accompanied by a net decrease in

the availability of and access to food, with calorie

consumption estimated to decrease across all

regions compared to baseline levels (Figure 11).

Food-calorie consumption decreases the most

in Sub-Saharan Africa, where calorie availability is

projected to fall by more than 8 percent if biofu-

els expand drastically.

One of the arguments in favor of biofuels

is that they could positively affect net carbon

emissions as an alterative to fossil fuels.That

added social benefit might justify some level of

subsidy and regulation, since these external benefits would

not be internalized by markets. However, potential forest

conversion for biofuel production and the impact of biofuel

production on soil fertility are environmental concerns that

require attention. As is the case with any form of agricultural

production, biofuel feedstock production can be managed in

sustainable or in damaging ways. Clear environment-related

efficiency criteria and sound process standards need to be

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

8

Figure 10—Meat and dairy prices (January 2000 = 100)

Jan-00

Jul-00

Source: Data from FAO 2007c.

Notes: Beef = USA beef export unit value; poultry = export unit value of broiler cuts;

butter = Oceania indicative export prices, f.o.b. Milk = Oceania whole milk powder indicative

export prices, f.o.b.

January 2000 = 100

Jan-01

Jul-01

Jan-02

Jul-02

Jan-03

Jul-03

Jan-04

Jul-04

Jan-05

Jul-05

Jan-06

Jul-06

Jan-07

Jul-07

50

100

150

200

250

300

Beef Poultry

Butter Milk

Figure 11—Calorie availability chang es in 2020 compared to baseline (%)

Source: IFPRI IMPACT projections.

Notes: N America = North America; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; S Asia = South Asia;

MENA = Middle East & North Africa; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean;

ECA = Europe & Central Asia; EAP = East Asia and Pacific.

-9 -6 -3 0

EAP

ECA

LAC

MENA

S Asia

SSA

N America

Biofuel expansion Drastic biofuel expansion

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

9

established that internal-

ize the positive and

negative externalities

of biofuels and ensure

that the energy out-

put from biofuel pro-

duction is greater

than the amount of

energy used in the

process. In general,

subsidies for biofuels

that use agricultural

production resources

are extremely anti-

poor because they

implicitly act as a tax

on basic food, which

represents a large

share of poor people’s

consumption expendi-

tures and becomes

even more costly as

prices increase, as shown above (von Braun 2007).

Great technological strides are expected in biofuel

production in the coming decades. New technologies

converting cellulosic biomass to liquid fuels would create

added value by both utilizing waste biomass and by using less

land resources.These second-generation technologies,

however, are still being developed and third-generation

technologies (such as hydrogene) are at an even earlier

phase. Even though future technology development will very

much determine the competitiveness of the sector, it will

not solve the food–fuel competition problem.The trade-offs

between food and fuel will actually be accelerated when

biofuels become more competitive relative to food and

when, consequently, more land, water, and capital are

diverted to biofuel production.To soften the trade-offs and

mitigate the growing price burden for the poor, it is

necessary to accelerate investment in food and agricultural

science and technologies, and the CGIAR has a vital role to

play in this. For many developing countries, it would be

appropriate to wait for the emergence of second-generation

technologies, and “leapfrog” onto them later.

Attempts to predict future overall food price changes

How will food prices change in coming years? This is one of

the central questions that policymakers, investors,

speculators, farmers, and millions of poor people ask.Though

the research community does its best to answer this

question, the many uncertainties created by supply, demand,

market functioning, and policies mean that no straightforward

answer can be given. However, a number of studies have

analyzed the forces driving the current increases in world

food prices and have predicted future price developments.

The Economic Intelligence Unit predicts an 11-percent

increase in the price of grains in the next two years and only a

5-percent rise in the price of oilseeds (EIU 2007).The OECD-

FAO outlook has higher price projections (it expects the

prices of coarse grains, wheat, and oilseeds to increase by 34,

20, and 13 percent, respectively, by 2016–17).The Food and

Agricultural Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) expects

increases in corn demand and prices to last until 2009–10, and

thereafter expects corn production growth to be on par with

consumption growth. FAPRI does not expect biofuels to have

a large impact on wheat markets, and predicts that wheat

prices will stay constant due to stable demand as population

growth offsets declining per capita consumption. Only the

price of palm oil—another biofuel feedstock—is projected to

dramatically increase by 29 percent. In cases where demand

for agricultural feedstock is large and elastic, some experts

expect petroleum prices to act as a price floor for agricultural

commodity prices. In the resulting price corridor, agricultural

commodity prices are determined by the product’s energy

equivalency and the energy price (Schmidhuber 2007).

In order to model recent price developments, changes in

supply and demand from 2000 to 2005 as well as biofuel

developments were introduced into the IFPRI IMPACT

model (see Scenario 1).The results indicate that biofuel pro-

duction is responsible for only part of the imbalances in the

world food equation. Other supply and demand shocks also

play important roles.The price changes that resulted from

actual supply and demand changes during 2000–2005 capture

a fair amount of the noted increase in real prices for grains in

those years (Figure 12).

6

For the period from 2006 to 2015,

the scenario suggests further increases in cereal prices of

about 10 to 20 percent in current U.S. dollars. Continued

depreciation of the U.S. dollar—which many expect—may

further increase prices in U.S.-dollar terms.

The results suggest that changes on the supply side

(including droughts and other shortfalls and the diversion of

food for fuel) are powerful forces affecting the price surge at

a time when demand is strong due to high income growth in

developing countries. Under a scenario of continued high

income growth (but no further supply shocks), the prelimi-

nary model results indicate that food prices would remain at

Table 5—Changes in world prices of feedstock crops and sugar by 2020 under

two scenarios compared with baseline levels (%)

SCENARIO 1 SCENARIO 2

Biofuel Drastic biofuel

Crop expansion

a

expansion

b

Cassava 11.2 26.7

Maize 26.3 71.8

Oilseeds 18.1 44.4

Sugar 11.5 26.6

Wheat 8.3 20.0

SOURCE: IFPRI IMPACT projections (in constant prices).

a

Assumptions are based on actual biofuel production plans and projections in relevant countries and regions.

b

Assumptions are based on doubling actual biofuel production plans and projections in relevant countries and regions.

high levels for quite some time.The usual sup-

ply response embedded in the model would

not be strong enough to turn matters around

in the near future.

Who benefits and who loses

from high prices?

An increase in cereal prices will have uneven

impacts across countries and population

groups. Net cereal exporters will experience

improved terms of trade, while net cereal

importers will face increased costs in meeting

domestic cereal demand.There are about four

times more net cereal-importing countries in

the world than net exporters. Even though

China is the largest producer of cereals, it is a

net importer of cereals due to strong domestic

consumption (Table 6). In contrast, India—also

a major cereal producer—is a net exporter.

Almost all countries in Africa are net importers

of cereals.

Price increases also affect the availability

of food aid. Global food aid represents less

than 7 percent of global official development

assistance and less than 0.4 percent of total world food

production.

7

Food aid flows, however, have been declining

and have reached their lowest level since 1973. In 2006,

food aid was 40 percent lower than in 2000 (WFP 2007).

Emergency aid continues to constitute the largest portion

of food aid. Faced with shrinking resources, food aid is

increasingly targeted to fewer countries—mainly in Sub-

Saharan Africa—and to specific beneficiary groups.

At the microeconomic level, whether a household will

benefit or lose from high food prices depends on whether

the household is a net seller or buyer of food. Since food

accounts for a large share of the poor’s total expenditures,

a staple-crop price increase would translate into lower

quantity and quality of food consumption. Household

surveys provide insights into the potential impact of higher

food prices on the poor. Surveys show that poor net

buyers in Bolivia, Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Zambia purchase

more staple foods than net sellers sell (Table 7).The impact

of a price increase is country and crop specific. For

instance, two-thirds of rural households in Java own

between 0 and 0.25 hectares of land, and only 10 percent

of households would benefit from an increase in rice prices

(IFPP 2002).

In sum, in view of the changed farm-production and

market situation that the poor face today, there is not much

supporting evidence for the idea that higher farm prices

would generally cause poor households to gain more on

the income side than they would lose on the

consumption–expenditure side. Adjustments in the farm

and rural economy that might indirectly create new income

opportunities due to the changed incentives will take time

to reach the poor.

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

10

Figure 12—Modeling the actual price change of cereals, 2000–2005 and

scenario 2006–2015 (US$/ton)

Source: Preliminary results from the IFPRI IMPACT model, provided by Mark W. Rosegrant

(IFPRI). In constant prices.

0

100

200

300

2000 2005 2010 2015

Rice Wheat Maize

Oilseeds Soybean

US$/ton

Table 6—Net cereal exports and imports

for selected countries

(three-year averages 2003–2005)

Country 1000 tons

Japan –24,986

Mexico –12,576

Egypt –10,767

Nigeria –2,927

Brazil –2,670

China –1,331

Ethiopia –789

Burkina Faso 29

India 3,637

Argentina 20,431

United States 76,653

SOURCE: Data from FAO 2007a.

Table 7—Purchases and sales of staple foods by

the poor (% of total expenditure of all poor)

Bolivia Ethiopia Bangladesh Zambia

Staple foods 2002 2000 2001 1998

Purchases by

all poor net

buyers 11.3 10.2 22.0 10.3

Sales by all

poor net

sellers 1.4 2.8 4.0 2.3

SOURCE: Adapted from World Bank 2007a.

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

11

M

any of those who are the poorest and hungriest today will still be poor and hungry in 2015, the target

year of the Millennium Development Goals. IFPRI research has shown that 160 million people live in

ultra poverty on less than 50 cents a day (Ahmed et al. 2007).The fact that large numbers of people continue

to live in intransigent poverty and hunger in an increasingly wealthy global economy is the major ethical, eco-

nomic, and public health challenge of our time.

Poverty and the Food and Nutrition Situation

The number of undernourished in the developing

world actually increased from 823 million in 1990 to 830

million in 2004 (FAO 2006a). In the same period, the share

of undernourished declined by only 3 percentage points—

from 20 to 17 percent.The share of the ultra poor—those

who live on less than US$0.50 a day—decreased more

slowly than the share of the poor who live on US$1 a day

(Ahmed et al. 2007). In Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin

America, the number of people living on less than US$0.50

a day has actually increased (Ahmed et al. 2007). Clearly,

the poorest are being left behind.

Behind the global figures on undernourishment, there

are also substantial regional differences (Figure 13). In East

Asia, the number of food insecure has decreased by more

than 18 percent since the early 1990s and the prevalence

of undernourishment decreased on average by 2.5 percent

per annum, mostly due to economic growth in China. In

Sub-Saharan Africa, however, the number of food-insecure

people increased by more than 26 percent and the preva-

lence of undernourishment increased by 0.3 percent per

year. South Asia remains the region with the largest num-

ber of hungry, accounting for 36 percent of all undernour-

ished in the developing world.

Recent data show that in the developing world, one of

every four children under the age of five is still under-

weight and one of every three is stunted.

8

Children living

in rural areas are nearly twice as likely to be underweight

as children in urban areas (UNICEF 2006).

An aggregate view on progress—or lack thereof—is

given by IFPRI’s Global Hunger Index (GHI). It evaluates

manifestations of hunger beyond dietary energy availability.

The GHI is a combined measure of three equally weighted

components: (i) the proportion of undernourished as a

percentage of the population, (ii) the prevalence of under-

weight in children under the age of five, and

(iii) the under-five mortality rate.The Index

ranks countries on a 100-point scale, with

higher scores indicating greater hunger.

Scores above 10 are considered serious

and scores above 30 are considered

extremely alarming.

From 1990 to 2007, the GHI improved

significantly in South and Southeast Asia,

but progress was limited in the Middle East

and North Africa and in Sub-Saharan Africa

(Figure 14).The causes and manifestations

of hunger differ substantially between

regions. Although Sub-Saharan Africa and

South Asia currently have virtually the same

scores, the prevalence of underweight chil-

dren is much higher in South Asia, while the

proportion of calorie-deficient people and

child mortality is much more serious in

Sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 13—Prevalence of undernourishment in developing countries,

1992–2004 (% of population)

Source: Data from FAO 2006a and World Bank 2007b.

Note: The size of the bubbles represents millions of undernourished people in 2004.

EAP—East Asia and the Pacific, LAC—Latin America and the Caribbean, SA—South Asia,

SSA—Sub-Saharan Africa, MENA—Middle East and North Africa, ECA—Eastern Europe

and Central Asia.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

-4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Prevalence of undernourishment 2004 (%)

SA

Annual change in prevalence of undernourishment 1992-2004 (%)

SSA

MENA

ECA

EAP

LAC

52

37

213

300

227

23

12

Table 8—Expected number of undernourished in millions,

incorporating the effects of climate change

Region 1990 2020 2050 2080 2080/1990 ratio

Developing countries 885 772 579 554 0.6

Asia, Developing 659 390 123 73 0.1

Sub-Saharan Africa 138 273 359 410 3.0

Latin America 54 53 40 23 0.4

Middle East & North Africa 33 55 56 48 1.5

SOURCE: Adapted from Tubiello and Fischer 2007.

Global Hunger Index

Figure 15—Trends in the GHI and Gross National Income per capita

(1981, 1992, 1997, 2003)

Source: Analysis by Doris Wiesmann (IFPRI) based on GHI data from Wiesmann et al. 2007

and gross national income per capita data from World Bank 2007b.

Note: Gross National Income per capita was calculated for three-year averages

(1979–81, 1990–92, 1995–97, and 2001–03, considering purchasing power parity).

Each triangle represents one of the four years:

1981, 1992, 1997, and 2003.

0

10

20

30

40

50

0 2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000

Gross National Income per capita

Ethiopia

India

Ghana

China

Brazil

Figure 14—Changes in the Global Hunger Index (GHI)

Source: Adapted from Wiesmann et al. 2007.

Note: GHI 1990 was calculated on the basis of data from 1992 to 1998. GHI 2007 was calculated

on the basis of data from 2000 to 2005, and encompasses 97 developing countries and 21

transition countries.

0

10

20

30

1990

2007

proportion of calorie-deficient people

prevalence of underweight in children

under-five mortality rate

South Asia

East Asia &

Pacific

Middle East &

N. Africa

L. America &

Caribbean

Sub-Saharan

Africa

Contribution of components to the GHI

1990

2007

1990

2007

1990

2007

1990

2007

In recent years, countries’ progress

toward alleviating hunger has been mixed.

For instance, progress slowed in China and

India, and accelerated in Brazil and Ghana

(Figure 15). Many countries in Sub-Saharan

Africa have considerably higher GHI values

than countries with similar incomes per

capita, largely due to political instability and

war. Index scores for Ethiopia moved up and

down, increasing during times of war and

improving considerably between 1997 and

2003.

Climate change will create new food

insecurities in coming decades. Low-income

countries with limited adaptive capacities to

climate variability and change are faced with

significant threats to food security. In many

African countries, for example, agricultural

production as well as access to food will be

negatively affected, thereby increasing food

insecurity and malnutrition (Easterling et al.

2007).When taking into account the effects

of climate change, the number of undernour-

ished people in Sub-Saharan Africa may triple

between 1990 and 2080 under these

assumptions (Table 8).

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

13

Conclusions

The main findings of this update on the world food

situation are:

• Strong economic growth in developing countries is a

main driver of a changing world food demand

toward high-value agricultural products and

processed foods.

• Slow-growing supply, low stocks, and supply shocks

at a time of surging demand for feed, food, and fuel

have led to drastic price increases, and these high

prices do not appear likely to fall soon.

• Biofuel production has contributed to the changing

world food equation and currently adversely affects

the poor through price-level and price-volatility

effects.

• Many small farmers would like to take advantage of

the new income-generating opportunities presented

by high-value products (meat, milk, vegetables, fruits,

flowers).There are, however, high barriers to market

entry.Therefore, improved capacity is needed to

address safety and quality standards as well as the

large scales required by food processors and

retailers.

• Poor households that are net sellers of food benefit

from higher prices, but these are few. Households

that are net buyers lose, and they represent the

large majority of the poor.

• A number of countries—including countries in

Africa—have made good progress in reducing

hunger and child malnutrition. But many of the

poorest and hungry are still being left behind

despite policies that aim to cut poverty and hunger

in half by 2015 under the Millennium Development

Goals.

• Higher food prices will cause the poor to shift to

even less-balanced diets, with adverse impacts on

health in the short and long run.

Business as usual could mean increased misery,

especially for the world’s poorest populations. A mix of

policy actions that avoids damage and fosters positive

responses is required.While maintaining a focus on long-

term challenges is vital, there are five actions that should

be undertaken immediately:

1. Developed countries should facilitate flexible

responses to drastic price changes by eliminating

trade barriers and programs that set aside

agriculture resources, except in well-defined

conservation areas. A world confronted with more

scarcity of food needs to trade more—not less—to

spread opportunities fairly.

2. Developing countries should rapidly increase

investment in rural infrastructure and market

institutions in order to reduce agricultural-input

access constraints, since these are hindering a

stronger production response.

3. Investment in agricultural science and technology by

the Consultative Group on International

Agricultural Research (CGIAR) and national

research systems could play a key role in facilitating

a stronger global production response to the rise in

prices.

4. The acute risks facing the poor—reduced food

availability and limited access to income-generating

opportunities—require expanded social-protection

measures. Productive social safety nets should be

tailored to country circumstances and should focus

on early childhood nutrition.

5. Placing agricultural and food issues onto the

national and international climate-change policy

agendas is critical for ensuring an efficient and pro-

poor response to the emerging risks.

14

Notes

1. The most food-insecure countries include the 20 countries with the highest prevalence of undernourishment and

the 20 countries with the highest number of undernourished people as reported in FAO 2006a. Six countries over-

lap across both categories.

2. The data on stocks are estimates that need to be interpreted with caution since not all countries make such data

available.

3. Carbon fertilization refers to the influence of higher atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide on crop yields.

4. Calculation based on data from Government of India 2007 and FAO 2007b.

5. The coefficient of variation of oilseeds in the past five years was 0.20, compared to typical coefficients in the range

of 0.08–0.12 in the past two decades. In the past decade, the coefficient of variation of corn increased from 0.09 to

0.22 (von Braun 2007).

6. The weather variables are partly synthesized because complete data are not available, so turning points on prices

will not be precise, but the trend captures significant change.

7. Calculations are for 2006 and are based on data from OECD 2007, FAO 2007a, and WFP 2007.

8. With height less than two standard deviations below the median height-for-age of the reference population.

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

15

References

Ahmed,A., R. Hill, L. Smith, D.Wiesmann, and T. Frankenburger. 2007. The world’s most deprived: Characteristics and causes of

extreme poverty and hunger. 2020 Discussion Paper 43.Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research

Institute.

Bank of Mexico. 2007. Indices de precios de genéricos para mercado nacional. Available at: www.banxico.org.mx/sitioin-

gles/polmoneinflacion/estadisticas/prices/cp_171.html.

Bouet,A., S. Mevel, and D. Orden. 2007. More or less ambition in the Doha Round:Winners and losers from trade liberal-

ization with a development perspective. The World Economy 30 (8): 1253–1280.

Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. 2007. Annual agricultural sample survey—2006/2007. Available at:

www.csa.gov.et/text_files/Agricultural_sample_survey_2006/survey0/index.html.

CEPEA (Centro de Estudos Avançados em Economia Aplicada). 2007. CEPEA/ESALQ ethanol index—São Paulo State.

Available at: www.cepea.esalq.usp.br/english/ethanol/.

Cline,W. R. 2007. Global warming and agriculture: Impact estimates by country.Washington, D.C.: Center for Global

Development and Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Cohen, B. 2006. Urbanization in developing countries: Current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustain-

ability. Technology in Society 28: 63–80.

Earth Policy Institute. 2007. U.S. corn production and use for fuel ethanol and for export, 1980–2006. Available at:

www.earth-policy.org/Updates/2006/Update60_data.htm.

Easterling,W.E., P.K. Aggarwal, P. Batima, K.M. Brander, L. Erda, S.M. Howden,A. Kirilenko, J. Morton, J.-F. Soussana, J.

Schmidhuber, and F.N.Tubiello. 2007. Food, fibre and forest products. In Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and

vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change, ed. M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge

University Press.

EIU (Economist Intelligence Unit). 2007.World commodity forecasts: Food feedstuffs and beverages. Main report, 4th

Quarter 2007. Available at:

www.eiu.com/index.asp?layout=displayIssueTOC&issue_id=1912762176&publication_id=440003244. (Access

restricted by password).

Ethiopian Grain Trade Enterprise. 2007. Commodities price for selected market. Available at:

www.egtemis.com/priceone.asp.

Euromonitor. 2007. World retail data and statistics 2006/2007, 4th edition. London: Euromonitor International Plc.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2003. Food outlook no. 5—November 2003. Rome.

————. 2005. Food outlook no. 4—December 2005. Rome.

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

16

————. 2006a. The state of food insecurity in the world 2006. Rome.

————. 2006b. Food outlook no. 2—June 2006. Rome.

————. 2007a. FAOSTAT database. Available at: www.faostat.fao.org/default.aspx.

————. 2007b. Food outlook—November 2007. Rome.

————. 2007c. International commodity prices database. Available at:

www.fao.org/es/esc/prices/PricesServlet.jsp?lang=en.

FAPRI (Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute). 2000. FAPRI 2000 U.S. and world agricultural outlook. Ames, Iowa.

————. 2007. FAPRI 2007 U.S. and world agricultural outlook. Ames, Iowa.

Fischer, G., M. Shah, F.Tubiello, and H. van Velhuizen. 2005. Socio-economic and climate change impacts on agriculture:An

integrated assessment, 1990–2080. Philosophical Transactions of Royal Society B 360: 2067–83.

Gabre-Madhin, E. 2006. Does Ethiopia need a commodity exchange? An integrated approach to market development.

Presented at the Ethiopia Strategy Support Program (ESSP) Policy Conference “Bridging, Balancing, and Scaling Up:

Advancing the Rural Growth Agenda in Ethiopia,” Addis Ababa, June 6–8.

Government of India (Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Office of the Economic Adviser). 2007.Wholesale price index

data. Available at: www.eaindustry.nic.in/.

Gulati,A., P.K. Joshi, and R. Cummings Jr. 2007.The way forward:Towards accelerated agricultural diversification and

greater participation of smallholders. In Agricultural diversification and smallholders in South Asia, ed. P.K. Joshi,A. Gulati,

and R. Cummings Jr. New Delhi: Academic Foundation.

Henniges, O. 2005. Economics of bioethanol production. A view from Europe. Presented at the International Biofuels

Symposium, Campinas, Brazil, March 8–11.

IEA (International Energy Agency). 2004. Biofuels for transport: An international perspective. Paris.

IFPP (Indonesian Food Policy Program). 2002. Food security and rice policy in Indonesia: Reviewing the debate.Working Paper

12. Jakarta.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2007a.World economic outlook database.Washington, D.C. Available at:

www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2007/02/weodata/index.aspx.

————. 2007b. International financial statistics database.Washington, D.C. Available at: www.imfstatistics.org/imf/.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2007. Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability.

Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ed. M.L.

Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden, and C.E. Hanson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

17

IRRI (International Rice Research Institute). 2007. Expert consultation on biofuels. Los Banos, Philippines,August 27–29.

Kumar P., Mruthyunjaya, and P.S. Birthal. 2007. Changing composition pattern in South Asia. In Agricultural diversification and

smallholders in South Asia, ed. P.K. Joshi,A. Gulati, R. Cummings Jr. New Delhi:Academic Foundation.

Morningstar. 2007. Morningstar quotes. Available at: www.morningstar.com/.

Mussa, M. 2007. Global economic prospects 2007/2008: Moderately slower growth and greater uncertainty. Paper pre-

sented at the 12th semiannual meeting on Global Economic Prospects, October 10.Washington, D.C.: Peterson

Institute.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2007a. Statistical data. Available at: www.stats.gov.cn/english/statisticaldata/yearly-

data/.

————. 2007b. China statistical yearbook 2007. Beijing.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2007. Development aid from OECD countries fell

5.1% in 2006. Available at http://www.oecd.org/document/17/0,3343,en_2649_34447_38341265_1_1_1_1,00.html.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) and FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of

the United Nations). 2007. OECD-FAO agricultural outlook 2007–2016. Paris.

Pingali, P. 2006.Westernization of Asian diets and the transformation of food systems: Implications for research and policy.

Food Policy 32: 2881–298.

Planet Retail. 2007a. Buoyant year forecast for global grocery retail sales. Press Release May 4. Available at: www.plane-

tretail.net/Home/PressReleases/PressRelease.aspx?PressReleaseID=54980.

————. 2007b.Top 30 ranking by Planet Retail reveals changes at the top. Press Release May 9. Available at: www.plan-

etretail.net/Home/PressReleases/PressRelease.aspx?PressReleaseID=55074.

Ravallion, M., S. Chen, and P. Sangraula. 2007. New evidence on the urbanization of global poverty.Washington D.C.:World

Bank.

Regmi,A., M. S. Deepak, J. L. Seale, Jr., and J. Bernstein. 2001. Cross-country analysis of food consumption patterns. In

Changing structure of global food consumption and trade, ed. A. Regmi.Washington, D.C.: United States Department of

Agriculture Economic Research Service.

Seale, J. Jr.,A. Regmi, and J. Bernstein. 2003. International evidence on food consumption patterns.Technical Bulletin No.

TB1904.Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service.

Schmidhuber, J. 2007. Impact of an increased biomass use on agricultural markets, prices and food security:A longer-term

perspective. Mimeo.

Tubiello, F. N., and G. Fischer. 2007. Reducing climate change impacts on agriculture: Global and regional effects of mitiga-

tion, 2000–2080. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74: 1030–56.

THE WORLD FOOD SITUATION

18

UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). 2006. Tracking the trend towards market concentration

the case of the agricultural input industry. Geneva.

————. 2007. World investment report 2007. Geneva.

UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund). 2006. The state of the world's children 2006: Excluded and invisible. New York.

von Braun, J. 2005. The world food situation:An overview. Prepared for CGIAR Annual General Meeting, Marrakech,

Morocco, December 6, 2005.

————. 2007. When food makes fuel—the promises and challenges of biofuels. Crawford Fund. Canberra,Australia.

WFP (World Food Programme). 2007. Food aid flows 2006. International Food Aid Information System (INTERFAIS).

Rome. Available at: www.wfp.org/interfais/index2.htm.

Wiesmann, D., A.K. Sost, I. Schöninger, H. Dalzell, L. Kiess,T. Arnold, and S. Collins. The challenge of hunger 2007. Bonn,

Washington, D.C., and Dublin: Deutsche Welthungerhilfe, International Food Policy Research Institute, and Concern.

World Bank. 2007a. World development report 2008:Agriculture for development.Washington, D.C.

————. 2007b. World development indicators.Washington, D.C.

Joachim von Braun is the director general of IFPRI.

INTERNATIONAL FOOD

POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE

2033 K Street, NW

Washington, DC 20006-1002 USA

Telephone: +1-202-862-5600

Fax: +1-202-467-4439

Email: ifpri@cgiar.org

www.ifpri.org