CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENTCLIMBING MANAGEMENT

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the DevelopmentA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

of a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Planof a Climbing Management Plan

››1

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > The Access Fund

The Access Fund

PO Box 17010

Boulder, CO 80308

Tel: (303) 545-6772

Fax: (303) 545-6774

E-mail: info@accessfund.org

Website: www.accessfund.org

The Access Fund is the only national advocacy organization whose mission keeps climbing areas open and conserves

the climbing environment. A 501(c)3 non-profi t supporting and representing over 1.6 million climbers nationwide in all

forms of climbing—rock climbing, ice climbing, mountaineering, and bouldering—the Access Fund is the largest US

climbing organization with over 15,000 members and affi liates.

The Access Fund promotes the responsible use and sound management of climbing resources by working in

cooperation with climbers, other recreational users, public land managers and private land owners. We encourage

an ethic of personal responsibility, self-regulation, strong conservation values, and minimum impact practices among

climbers.

Working toward a future in which climbing and access to climbing resources are viewed as legitimate, valued,

and positive uses of the land, the Access Fund advocates to federal, state, and local legislators concerning public

lands legislation; works closely with federal and state land managers and other interest groups in planning and

implementing public lands management and policy; provides funding for conservation and resource management

projects; develops, produces, and distributes climber education materials and programs; and assists in the

acquisition and management of climbing resources.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE ACCESS FUND:

Visit http://www.accessfund.org.

Copies of this publication are available from the Access Fund and will also be posted on the Access Fund website:

http://www.accessfund.org.

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT:

A Guide to Climbing Issues and the Production of a Climbing Management Plan. Compiled by Aram Attarian, Ph.D.

and Jason Keith, Access Fund Policy Director.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

For assistance with this publication, special thanks go to: Access Fund staff; Mark Eller and Jeff Achey, Editor; The

American Alpine Club; Steve Dieckhoff, Illustrator; Timothy Duck, Wildlife Biologist, Bureau of Land Management,

UT; Leave No Trace, Inc., CO; The National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS); Claudia Nissley, Cultural Resource

Specialist, CO; Outdoor Industry Association; Jane Rodgers, Vegetation Specialist, Joshua Tree National Park, CA;

and Wildlife Conservation Society, NY.

COVER PHOTOGRAPHY: © 2008 Jim Thornburg

LAYOUT AND DESIGN: © 2008 The Access Fund

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CONTROL NUMBER: 2001130563

››2

CMP

| Executive Summary

Climbing, once an obscure activity with few participants, has become a mainstream form of outdoor recreation.

Climbing occurs in unique environmental settings such as cliff sides, canyons, and alpine areas, which can also

harbor valuable natural and cultural resources. These unique settings also present land managers with distinctive

challenges. Climbing activities take place primarily off-trail, away from developed facilities, and historically have

had little oversight by land managers or owners. Given the ever-growing popularity of climbing and other outdoor

recreation activities, potential impacts on resource values must be considered and appropriate management

actions taken. This need to develop climbing management strategies has led the Access Fund to offer the climbing

management guidelines presented herein. This document outlines successful climbing management practices that

provide for climbing access while protecting resource values. The following chapters address both fundamental

aspects and narrowly-focused issues pertaining to climbing management.

Chapters 1 provides a schematic assessment of a typical climbing area that may prove helpful in examining the

effects of climbing activity on resource values. This illustration is applied to the section on impacts to vegetation.

Chapter 2 presents information on various climbing management issues related to natural resources. Each

topic is discussed by identifying primary issues, citing relevant literature and research, and providing examples

of Management Practices that Work. These practices are well-defi ned methods and management techniques

developed and successfully implemented by various resource management agencies and climber organizations

across the nation to help address climbing management concerns.

Chapter 3 includes a presentation on Cultural Resources and Climbing Activity with an emphasis on issues

relating to Native American sacred sites, archeological and historic sites, pictographs and petroglyphs, and issues

pertinent to the National Historic Preservation Act. A schematic assessment of a climbing area is presented in this

section in relation to cultural resources. Chapter 4, Social Impacts and Climbing, addresses visual impacts and

other considerations such as pets, noise, and litter. Chapter 5 analyzes Activities and Areas of Special Concern

to provide information and awareness on a growing number of climbing activities such as bouldering, ice climbing,

dry tooling, and alpine climbing. This chapter also discusses unique and sometimes controversial climbing

environments like wilderness and caves, and presents a short summary on climbing and economic considerations.

Chapter 6 outlines Climbing Management Methods and discusses specifi c Philosophies and Tools used by land

managers to respond to specifi c climbing issues such as visitor capacity, recent increases in climber visitation,

and the development of new climbing routes. Chapter 7 provides a template for the Production of a Climbing

Management Plan. Emphasis in this chapter is placed on developing clearly stated goals and objectives, defi ning

the scope and longevity of the CMP, and conducting a thorough review of climbing activity by including members of

the relevant user group. An outline for a successful CMP is also suggested.

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > The Access Fund

››3

CMP

| Table of Contents

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT:

A Guide to Climbing Management and the Production of a Climbing Management Plan

FORWARD: Introduction and the Purpose and Need of a Climbing Management Plan 1

Chapter 1. Assessment of a Climbing Area 7

Chapter 2. Climbing and Natural Resources 8

Ecological Impacts 8

Climber Trails 9

Bivouac and Backcountry Camping 10

Human Waste 11

Vegetation 13

Water Resources 16

Wildlife 17

Chapter 3. Cultural Resources and Climbing Activity 21

Assessment of Impacts to Cultural Resources 22

Chapter 4. Social Impacts and Climbing 24

Visual or Aesthetic Impacts 25

Fixed Safety Anchors 27

Placement of Bolts as a Resource Protection Tool 27

Liability and Fixed Anchors 28

Pets 30

Noise 31

Litter 31

Guide Services and Organized Climbing Groups 32

Parking and Transportation 34

User Fees 35

Safety and Risk Management 35

Liability 35

Search And Rescue 36

Economic Considerations 37

Chapter 5. Activities and Areas of Special Concern 38

Bouldering 39

Ice Climbing 42

Alpine Areas 43

Designated Wilderness 44

Wilderness and Solitude 45

Wilderness and Fixed Anchors 46

Caves 48

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > Table of Contents

››4

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > Table of Contents

CMP

| Table of Contents | Continued

CHAPTER 6: Climbing Management Methods 49

Philosophies and Tools 49

Visitor Capacity 50

Increase in Climber Visitation 51

New Climbing Routes 52

CHAPTER 7: Production of a Climbing Management Plan (CMP) 55

Suggested Outline of CMP Contents 56

Hallmarks of a Successful CMP 56

Guidelines for Preparing a CMP 56

APPENDICES:

A ) Types of Climbing Defi ned 62

B ) Glossary of Climbing Terms 64

C ) Outreach and the Development of Education Materials 66

D ) Funding and Volunteer Assistance for Climbing Management 68

E ) Contacts on Climbing Issues 69

F ) Utilizing the Resources of the Access Fund 69

G ) Bibliography and References 71

INDEX: 75

››5

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > Introduction

PURPOSE AND NEED FOR THIS

DOCUMENT

The Access Fund was established in 1990 to resolve

issues of climbing access and education. The

organization provides information, human resources,

and grants for access improvements or impact

mitigation, and works closely with climbing advocates

and land managers on access issues, resource

protection, and climbing management initiatives. With

climbing activity on the increase (Outdoor Industry

Foundation 2006), policies and management plans

are being developed throughout the United States that

will have signifi cant effects on climbing access and

experiences in the future. We intend this document

to assist to those involved or interested in climbing

management, and encourage greater consistency in

climbing management policy.

This document is intended for use by land managers,

recreation planners, and climbing representatives (and

any other interested members of the public) who are

working on climbing management issues. It is designed

to reach a range of audiences, with widely varying

management experience and needs. This manual

introduces typical climbing-related issues and suggests

management responses that have proven successful

in the past. The level of management will depend on

the mandate of the managing agency, the relative

importance of climbing compared to other recreation

uses in that area, and staffi ng and budgetary resources.

This document can assist with:

•Providing an enjoyable public land climbing

experience.

•Review of issues related to climbing management

•Production of a climbing management plan

•Identifi cation of management alternatives to address

climbing and resource-protection issues

•Identifying the different recreational values associated

with climbing.

•Coordinating with climbing organizations and local

climbing representatives for the purposes of gathering

information and participating in development and

implementation of climbing management policy.

If you have additional information or comments on

this document please contact the Access Fund:

info@accessfund.org, (303) 545-6772.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades, outdoor recreation

activities that contain the elements of risk and

adventure have grown in popularity (Cordell 1999). The

adventure sport of rock climbing, a highly visible and

diverse activity, is no exception to this growth. More

people than ever are participating in climbing in its

many forms—bouldering, sport climbing, ice climbing,

big-wall climbing, and mountaineering (Appendix A).

The primary resources for climbing include cliffs, talus,

glaciers, frozen waterfalls, and boulderfi elds, which

are found in a variety of environments. Currently, more

than 2,000 climbing areas have been documented

in the United States, with almost half (47%) of these

found on federal lands (Toula 2003; Stuart-Smith 2003).

Participation rates have been on the rise for the past 25

years. Beginning in the 1980s, participation in climbing

increased 8% from 1980 to 1984 and 12% between

1985 and 1989 (Moser 1990). The 1994-95 National

Survey on Recreation and the Environment reported

300,00 to 400,000 active rock climbers in the United

States, with this number expected to increase 50

percent by year 2050 (Cordell 1999).

More than any other issue, the increase in climber

visitation has driven recent discussions about climbing

management and the development of climbing

management plans. Climbing is as much about

intimacy with nature and exploration of wild places

as it is about personal challenge. As the number of

climbers increases, greater demands will be placed on

the vertical and surrounding environments to support

the various types of climbing activities. As a result,

the climbing experience may be diminished when

the environment is degraded. However, the impacts

associated with climbing activities depend less on

the total number of climbers than on the spatial and

temporal concentrations of climbers in particular

areas. Historically, climbers have had a high standard

of environmental awareness and stewardship—for

example, climbers such as David Brower were

instrumental in passing the 1964 Wilderness Act. Most

managers will acknowledge that climbers as a group

support programs that protect natural resources, as

well as those that protect resources with cultural and

historic values.

CMP

| Forward

››6

CMP

| Chapter 1 | A Guide to Climbing Management

A Schematic Breakdown of a Climbing Area

Illustration: © S. Dieckhoff

CHAPTER 1: A GUIDE TO CLIMBING MANAGEMENT

This chapter addresses the various climbing management issues and

examples of management responses. Assessment of a Climbing Area

introduces the reader to issues that have historically appeared when

climbers begin to use a climbing area in signifi cant numbers.

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > A Guide to Climbing Management

› › 7

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > Assesment of a Climbing area

ASSESSMENT OF A CLIMBING AREA

This section provides an overview of the unique

management issues related to climbing.

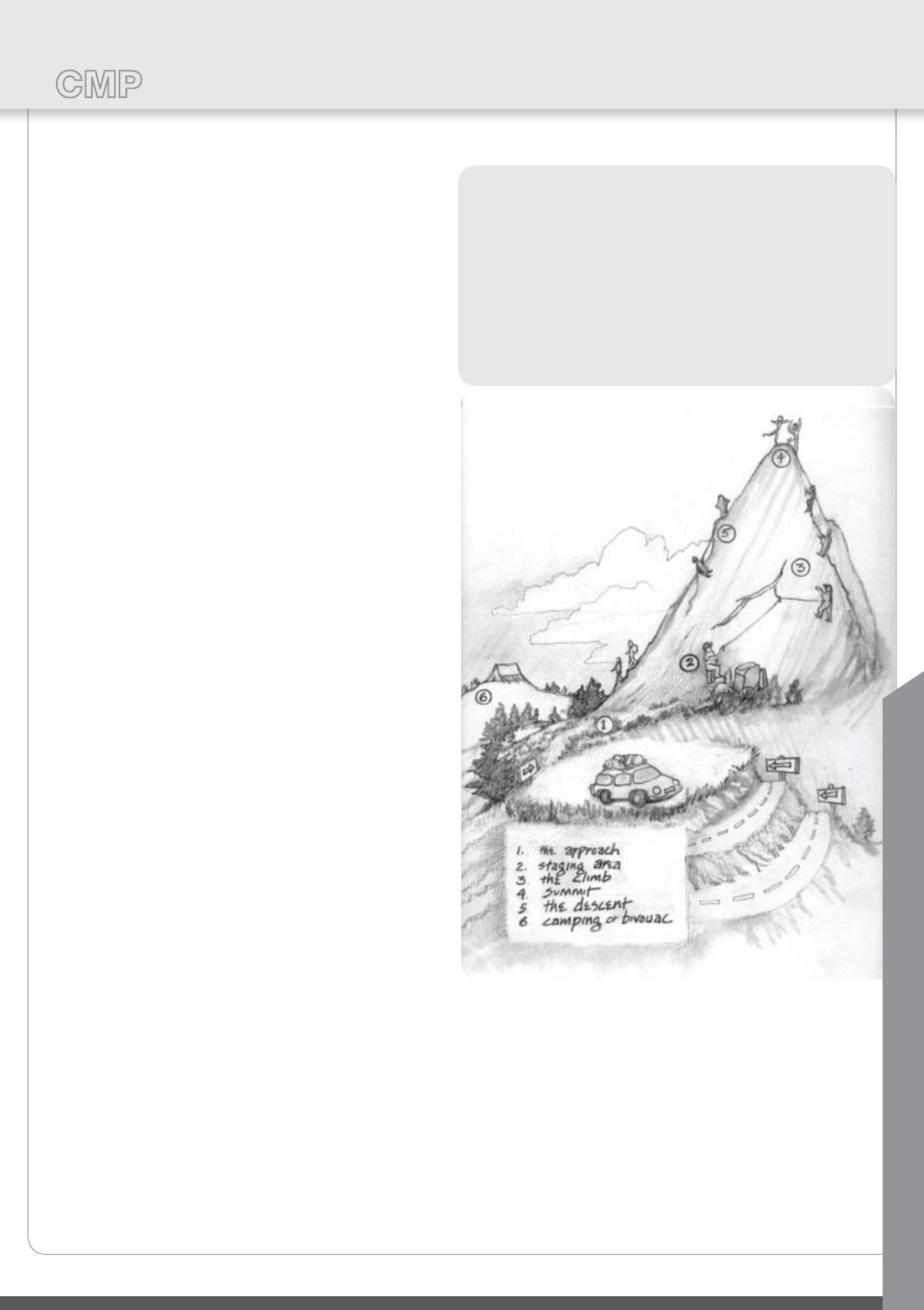

The areas affected by a climbing visit can be split into six

zones. Inspecting these individual zones can help clarify

how, where, and during what stage of a visit climbing

activity may affect rare plants, animals, or archaeological

deposits. This scheme can also assist in distinguishing

the effects of climbers from the effects of other less

conspicuous recreation visitors, such as hikers, who

may also frequent the various zones. The zone scheme

of assessment and other information-gathering tools

can help ensure that management responses accurately

target the correct sites of impact and the use practices

responsible for impact.

A typical climbing visit may be considered to pass

through six zones:

1. The approach to the climb (see glossary for

technical defi nitions of climbing terminology). The

“approach” is the route used to travel from the parking

area to the base of the rock or mountain. It may or may

not include discernible climber trails.

2. The staging area. The approach ends at the “staging

area,” typically the base of the cliff where climbers

prepare to climb and sometimes leave backpacks which

will be retrieved after the descent. In some cases, the

staging area will be at the top of the cliff. Of all the zones

used by climbing visitors, the staging area is typically the

most heavily impacted.

3. The climb. The “climb,” often called the “route,” is

the line of travel up the cliff or mountain. This zone is

typically 6 to 8 feet in width, follows a line that may be

straight or very irregular, depending upon the climbing

terrain, and will extend from the base to the summit, or

sometimes to a fi xed anchor below the summit.

4. The summit. The “summit” is either the top of a

mountain or the rim of a cliff, where one or more climbs

terminate.

5. The descent. The “descent” is the route by which

climbers return to either the staging area or to the

parking area where their visit originated. In some cases,

the descent will involve a climber trail, while in other

cases it may entail a rappel down the rock face.

6. The camping or bivouac area. This zone is the area

used by climbers for overnight stays during the climbing

visit.

In this document, the schematic assessment will be

used in the sections on Impacts to Vegetation and

Cultural Resources. In addition to these sample uses,

the scheme can also be applied in the assessment of

other resources or effects mentioned in this document.

Site visits and surveys may be carried out periodically to

record effects in each zone. Ideally, some baseline data

will be available from prior inventory and monitoring.

This information may then be evaluated in its contextual

environment to determine whether management

intervention is required.

CMP

| Chapter 1 | Assessment of a Climbing Area

Climbers at the base of Super Crack Buttress, Indian Creek, UT.

Photo: © Celin Serbo

››8

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > Ecological Impacts

Both resource managers and researchers have reported

a variety of impacts related to rock climbing (Attarian

and Pyke 2000). Soil erosion, the development of

social trails, damage to vegetation both on and off

the rock, improper disposal of human waste, and

disturbance to wildlife have been reported as a result

of climbing activity. Visual impacts to the rock and its

environs, the use of fi xed anchors, potential damage

to historical and cultural sites, and negative recreation

experiences by non-climbers have also been identifi ed

as climbing-related concerns. Impacts have the

potential to compromise the objectives of conserving

the natural environment, can make recreation areas less

attractive or functional to the visitor, and can detract

from the recreation experience through crowding,

confl icts between users, and depreciative behavior

(Cole 1986; McAvoy and Dustin 1983). The potential

impacts associated with outdoor recreation activities like

rock climbing can be divided into three primary areas:

ecological, cultural, and social impacts.

The term “impact” was defi ned by Lucas (1979), as

a neutral term synonymous with change. In contrast,

“damage” and “deterioration” suggest negative changes

in natural resource conditions. However, at least one

study, Hammitt and Cole (1998), defi nes “impact”

as an undesirable change in environmental or social

condition of a recreation site or experience. Impacts are

dependent on three major factors: (1) the amount and

distribution of use, (2) the type and behavior of visitors,

and (3) the ecosystem and its condition (Hendee,

Stankey and Lucas 2005).

ECOLOGICAL IMPACTS

Ecological impacts are those impacts that have

a potential effect on the biological and physical

characteristics of a site or resource, thus making the

area less natural (Hendee, Stankey and Lucas 1990).

While some climbing impacts are similar to those found

in other recreation environments (for example camping

and hiking), managing rock climbing activity poses

special challenges due to the unique character of the

climbing environment, which is spatially diverse and

encompasses both a horizontal and vertical perspective.

The ecological issues presented in the following section

focus on climber trails, bivouacking and backcountry

camping, human waste disposal, vegetation, water

resources, and wildlife.

CLIMBER TRAILS

Many of the trails found in park and natural areas were

originally designed to serve non-recreational uses.

Some of these uses include fi re and logging roads,

livestock and game trails, and trade and travel routes.

Climbers use trails to access and egress climbing areas.

Unlike hiking trails that are designed, constructed, and

maintained by professionals, some trails to climbing

sites are created by climbers when new climbing areas

are developed. Climber trails usually “follow the path

of least resistance,” avoiding obstacles and minimizing

the effort to reach a climbing destination (DeBenedetti

1990). In some cases trails may be ill-defi ned causing

climbers to unknowingly take several trails to the same

destination.

Sometimes called “social trails,” these trails develop

as climbers make repeated visits to climbing-specifi c

destinations that are not serviced by existing trail

systems, or move around in predictable ways within a

climbing area. Typically, climber trails develop in three

general locations: 1) along the quickest route from a

parking area to the climbing site; 2) on the simplest

descent from the top of a mountain or cliff; and 3) on

routes between cliffs and boulders within the climbing

site (DeBenedetti 1990).

The most critical problems associated with trails are soil

compaction, trail widening, trail incision, and soil loss.

Trail degradation is usually a function of site durability,

type of use, and use behavior rather than simply the

amount of use (Leung and Marion 1996). The majority of

environmental changes to trails occur during initial trail

development. Once a trail becomes established, factors

such as soil characteristics, topography, ecosystem

characteristics, climate, and local vegetation’s

resistance and resilience will dictate its prominence in

the landscape (Hammitt and Cole 1998). Climber trails

tend to be primitive with minimal improvements, are

often sited on steep slopes, with loose soils and “scree”

common elements.

Climbers, like other outdoor enthusiasts, have the

potential to disturb soil, particularly in heavily used areas

or where environmental and other factors cause these

areas to be more susceptible to damage. Damage to

soil can limit aeration, affect soil temperature, moisture

content, nutrition, and soil micro-organisms. Erosion,

the most damaging impact to soil, occurs primarily

through the development and use of trails. Problems

may be more serious at higher elevations where the soil

is poor and the growing season shorter (Hammitt and

Cole 1998). Climber trails that are located on soils with

high gravel or mineral content have been found to be

less prone to soil erosion. These materials are not as

easily eroded by water or wind and act as fi lters, binding

and holding on to fi ner soil particles (Leung and Marion

1996).

CMP

| Chapter 2 | Climbing and Natural Resources | Ecological Impacts

CHAPTER 2: CLIMBING AND NATURAL RESOURCES

This chapter introduces and discusses a variety of environmental concerns including trails, camping, human waste,

vegetation, water resources, and wildlife.

› › 9

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > Climber Trails

Staging areas and cliff tops are subject to impacts by

other recreationsists such as hikers, backpackers, and

sightseers (Wood, Lawson and Marion 2006; Williams

1990; Long et al. 2003). For example, in California’s

Yosemite National Park, El Capitan Meadow, located

just south of the base of El Capitan, is a popular visitor

destination, especially for tourists observing rock

climbers on “El Cap.” Conditions in the meadow are

becoming increasingly degraded, due in part to a lack of

designated trails and extensive use of social trails. Soil

compaction in this area has been identifi ed as a potential

problem (Ortiz 2006).

The type of climbing that occurs in an area may also

have an affect on the amount of impact an area receives.

Recent research conducted in Kentucky’s Red River

Gorge found impacts to staging areas are different for

sport and traditional (“trad”) climbing. Trail quality, the

number of similarly rated climbs in the area, and the

presence of overhanging rock were found to contribute

to staging area impacts for sport climbs. Factors

contributing to impacts associated with traditional

climbs, on the other hand, include the rating of the climb,

climb quality, approach trail length, and the presence of

overhanging rock (Carr 2006).

Soils in arid environments like those found in Joshua

Tree National Park, CA, and in Arches and Canyonlands

National Parks, UT, may contain cryptobiotic crusts,

which consist of mosses, lichens and blue-green algae

known as cynobacteria. These crusts are important

to the environment, since they increase the water-

holding capacity of soil, increase nutrient cycling, limit

the invasion of weedy, non-native annual grasses,

and reduce soil erosion. Any type of disturbance—for

example hiking and climbing—can compromise the

sediment associated with these crusts (Overlin et al.

1999).

MANAGEMENT PRACTICES THAT WORK

CLIMBER TRAILS

If many climbers use an area, some degree of

formalization and stabilization of climber trails will

eventually become desirable. Some climber trails

may be redundant or adversely affect resource or

aesthetic values. Such trails can be minimized or in

some cases eliminated. Local climbing representatives

can provide input on the minimum trail requirements

to access climbing locations. Management response

may initially include conducting a climber trail inventory.

Local climbing guidebooks will often describe climber

access routes, descent routes, and locations of other

climbing-related trails. Consultation with a local climbing

representative or arranging a joint site visit may also help

with climber-trail inventory.

Once trails are documented (typically GPS techniques

are used), a map is created. If necessary, a trails plan

can be developed to eliminate redundant or unnecessary

trails. Some trails may be targeted for stabilization or

upgrading to withstand heavier traffi c, while others may

be closed to protect sensitive resources, and replaced

with new, re-routed trails. This approach was taken by

managers in North Cascades National Park, WA, to

restore the Eldorado Creek drainage, a popular route

used by climbers to access the Eldorado Glacier. The

route had become deeply rutted and eroded. Following

an environmental assessment, a 1,300 foot section of

the trail was rerouted to divert climbers to more resilient

terrain which could withstand impacts that the damaged

area could not. This project was the fi rst attempt by

the park to rehabilitate recreational climbing impacts in

a cross-country or non-trailed area. (North Cascades

National Park 1997).

Local climbing representatives may prove helpful in

dispersing information concerning desired changes in

climber-trail use. Other management options include

signing of management-preferred trails, and brochure,

kiosk, and poster information concerning site advisories

or area closures. There have been many examples of

successful climber trail management. At City of Rocks

National Reserve, ID, climbers and hikers originally used

(and then expanded) livestock trails through sagebrush

vegetation. A park-wide trails plan was developed to

identify a rational trails network and mitigate impacts

(U.S. Department of the Interior 1988).

At Joshua Tree National Park, CA, climber-trail networks

have been formalized using a special climber-specifi c

symbol. This is produced in the form of a weather-

resistant sticker that can be applied to standard trail-

marking carsonite posts.

The symbol (an image of a carabiner—a piece of

climbing equipment) is recognizable to climbers, but

not the general public (Joshua Tree National Park et al.

2000).

CMP

| Chapter 2 | Climbing and Natural Resources | Climber Trails

At Joshua Tree National Park, CA. A special climbing

symbol is used on standard path–marking carsonite

posts to mark climbing access trails. These signs on

the approach to the Hall of Horrors climbing area direct

visitors and reduce the development of duplicate trails.

Photo: © The Access Fund Collection

››10

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > Bivouac and Backcountry Camping

CMP

| Chapter 2 | Climbing and Natural Resources | Bivouac and Backcountry Camping

“Cryptic” trails have also been used to limit non-climber

access in areas with sensitive habitat. Such trails are

designated on a park-wide trails plan but not signed

to the general public. This technique has been used

at Snow Canyon State Park, UT, to allow climbing

access to Hidden Canyon, a narrow riparian canyon

with high ecological value. Climber trails may see low

traffi c volume or access steep and diffi cult terrain,

and thus may merit special design and maintenance

specifi cations that would be inappropriate for high

volume multi-visitor use trails. Collaboration between

park management and the climbing community

improved trails, created belay platforms, and erected

directional signs at Smith Rock State Park, OR,

to control trail erosion and enhance the climbing

experience.

BIVOUAC AND BACKCOUNTRY CAMPING

Camping or bivouacking may be required as part of

a climbing objective. This may take place either on

the approach, on the climb itself, or on the descent.

Unplanned bivouacs are not uncommon, and typically

occur after a long backcountry route not completed

by nightfall. Climbing in the interior of mountain ranges

or on remote cliffs usually requires a planned camping

experience to put the climbers in position to do a long

route requiring an early start. Sometimes there will be

a need to camp for several days in one area if a long

and challenging route is intended (which might require

several attempts), or if there are several route objectives

in the area. Climbing on some of the large cliff faces

of Yosemite, Zion, Rocky Mountain, and Black Canyon

of the Gunnison National Parks may require bivouacs

on the climb itself. Hanging tents called “portaledges”

provide shelter and are designed to withstand minor

storms during a multi-day climbing ascent.

MANAGEMENT PRACTICES THAT WORK

As climbing becomes more popular, climbers

visiting well known climbing areas will require additional

camping areas. Climbers in the New River Gorge

National River, WV, and the Obed Wild and Scenic River,

TN, have indicated a need for public campgrounds.

The American Alpine Club is working with the Mohonk

Preserve and the state of New York in developing a

climbers’ campground. Under the proposal, the state

would assist in the development of a 45-acre, 20-site

campground scheduled to open in 2008 (American

Alpine Club 2005).

Volunteers on a trail-building project at North Table

Mountain, Colorado. Funding for materials and

trail design can also be obtained from climbing

organizations. Photo: © Access Fund Collection

Permits are required for overnight bivouacs

in Rocky Mountain National Park to access

popular alpine climbing areas such as the

Petit Grepon. At the backcountry ranger

offi ce, permit holders are provided with a

mapped location of the site they should

use and information on minimizing impacts

at bivouac sites. Photo: © K. Pyke

››11

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > Human Waste Disposal

Bivouacking must be considered a fundamental aspect

of the climbing experience in many areas. If the area

receives a high level of use, management response

may include outreach to ensure low-impact practices,

site monitoring, the designation of bivouac sites,

permit requirements, or, occasionally, the provision of a

primitive facility in order to reduce human impacts over

a wider area. For a sample of a heavily used area, see

the backcountry camping and bivouac policy for Rocky

Mountain National Park, CO (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bivouac Permit Rocky Mountain National Park

A bivouac is a temporary, open-air encampment

established between dusk and dawn and is issued only

to technical climbers. The permit also provides technical

climbers with an advanced position on long, one-day

climbs and/or climbs that require an overnight stay on

the rock face. All bivouacs require permits. Permits must

be in your possession while in the backcountry.

You must be within a designated bivouac area. Your

bivouac should on a durable surface such as rock or

snow as close to the base of the climb as possible or on

the face. Reservations may be made for the restricted

areas on or after March 1st, by mail, in person, and by

phone (through May 15th).

A total of 7 nights may be used in the SUMMER. Stay no

more than 3 nights at any spot, then move. An additional

14 nights are allowed in WINTER. In Winter, you may use

a tent.

A vehicle/parking permit will be issued for all vehicles

parked at the trailhead. Have the vehicle license

number(s) available when you get your bivouac permit.

The parking permit must be displayed on the vehicle

dashboard.

Bivouac Parameters:

• A climbing party is limited to a maximum of 4 people;

all must climb.

• A site must be 3-1/2 miles or more from the trailhead

• A climb must be 4 or more pitches, roped, technical

climbing.

• A site must be off all vegetation. You must sleep on

rock or snow.

• No tents are allowed. You may use a ground cloth.

• Pets, weapons, & vehicles are not allowed.

(Rocky Mountain National Park 1999)

In some areas with big-wall climbing opportunities, such

as Zion National Park, UT,

http://www.nps.gov/zion/planyourvisit/permits.htm, a

permit is required to bivouac on multi-day climbs.

Where permit processes are in place, they should be

well advertised to users to avoid unintentional non-

compliance. The process for obtaining a permit should

be straightforward. The Black Canyon of the Gunnison

National Park, CO, uses a self-service permit system

located at a kiosk near the climber descent route into the

canyon. Reservation-only permit systems have proven

to be problematical for both climbers and managers.

Climbing is a weather-dependent activity, and bad

weather conditions lead to late cancellations, while

good weather may create a sudden demand for permits.

Depending upon the specifi c climbing route, it may be

daily or weekly forecasts that infl uence demand, creating

signifi cant administrative challenges for a fair and

accessible permit-distribution system.

HUMAN WASTE DISPOSAL

The disposal of human waste is an important issue in the

management of climbing as it can create human health

problems through direct or indirect contact with drinking

water, cause negative reactions of climbers and non-

climbers who come in contact with improperly disposed

of human waste (and the impact this may have on their

recreation experience), and the transmission of disease-

causing pathogens from human feces (Cilimburg, Monz

and Kehoe 2000).

Human waste generated by climbers can be managed in

the same ways as waste from backcountry hikers. Site

assessment can identify whether impacts are due to

poor disposal methods or long-term cumulative effects,

and appropriate management strategies can then be

designed. In general, trailhead toilets and other waste-

disposal facilities will be used if available. Many climbers

may be aware of minimum-impact waste disposal

practices, and this knowledge can be reinforced by

education outreach. The handbook Skills and Ethics for

Rock Climbing (Leave No Trace

2001) describes ways

climbers can minimize their impacts. Climbers from

foreign countries may have different waste-disposal

standards. Building awareness and compliance among

foreign visitors should be incorporated in outreach

programs, for example, by producing education

materials in the primary languages of foreign climbers.

Grant assistance can be obtained from climbing

organizations for such projects. The best methods

for human waste disposal will vary with different

environments.

Educating climbers on the proper disposal of waste is an

important management and public health consideration.

In the past, fi nding a solution to the human-waste

problem was diffi cult due to a lack of climber

compliance, inadequate funding, disposal issues, and

differences in environments (Nickel 1994). However this

attitude towards human waste disposal is changing.

CMP

| Chapter 2 | Climbing and Natural Resources | Human Waste Disposal

››12

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN > Humna Waste Management

MANAGEMENT PRACTICES THAT WORK

HUMAN WASTE DISPOSAL

Managers in Grand Teton National Park, WY, recently

implemented a new system of human waste removal and

reduce the need for the vault toilet located on the Grand

Teton’s Lower Saddle (Anzelmo and Skaggs 2002). The

new system provides mountain guides, their clients, and

individual climbers with special triple-layer mylar bags,

called “Restop2,”

http://www.whennaturecalls.com to encourage a new

“pack-out” method, replacing the need for the stationary,

high-elevation toilet. Restop2 is a blend of polymers and

enzymes housed in a specially designed plastic bag.

The system works by containing human waste and then

converting it into an environmentally friendly material

that can be packed out in the onetime-use bags and

deposited in the appropriate trash receptacles located

at the Lupine Meadows trailhead. Similar practices are

being tried by Utah Open Lands at Castle Valley and the

BLM at Indian Creek, UT (Osius 2006), where a pack-in/

pack-out policy has been instituted promoting the use of

Wag Bags http://www.thepett.com/, a product similar to

Restop2, to pack out human waste.

Poop Tubes: In popular big-wall climbing areas that

require bivouacs such as Zion and Yosemite National

Parks it is mandatory to remove human waste by

carrying a “poop tube” (specially designed human waste

storage container) or other type of container, which is

hauled with equipment up the climb. The poop tube

is constructed from PVC pipe. The climber defecates

into a paper bag, adds a small amount of kitty litter

to reduce odors, and places the bag into the tube.

After descending, the climber empties the contents of

the tube (less any plastics bags) into any vault toilet.

If climbers are using Wag Bags or Restop2 with their

poop tubes then the bags may be disposed of in any

conventional garbage can, thus making waste disposal

more convenient for climbers and less problematic for

agencies to manage.

Climbing equipment manufacturers are beginning

to promote the “pack it in, pack it out” principle by

developing waste management systems. One product,

the Waste Case, developed by Metolius

http://www.metoliusclimbing.com/wastecase.htm is

designed to carry waste bags on big walls.

Waste Case Disposal System: Clean Mountain Can

(CMC). Denali National Park and Preserve, AK, has

an ongoing research program on human waste in the

glacier environment. Outhouses are provided on glaciers

at some of the most popular Denali camping areas and

climbs. During 2001, the NPS ran a series of successful

trials with “clean mountain cans” (CMC)—plastic waste-

disposal receptacles (a smaller, lighter version of a

commercially designed river toilet box) issued voluntarily

to climbers going above 14,200 feet on the West

Buttress route. During the 2003 climbing season, the

box toilet was removed from its 17,200-foot location and

replaced by the CMC. The CMC is now the method for

the removal of human waste from the mountain above

14,200 feet. http://www.nps.gov/archive/dena/home/

mountaineering/cmc.htm. This project was supported

by a $5500 Access Fund grant and has been very

successful.

Blue Bags: On Mount Rainier and other Cascade peaks,

human waste is deposited in “Blue Bags” available from

ranger stations and high camps. The Blue Bag system