Distribution

Management Plan

Guide 2.0

January 2022

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

This page intentionally left blank

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Organization ............................................................................................................ 4

1. Purpose ................................................................................................................................... 4

2. Background ............................................................................................................................. 4

3. Supersession ........................................................................................................................... 4

4. Document Management and Maintenance ............................................................................ 5

Chapter 2: Introduction to Distribution Management .............................................................. 6

Overview ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6

1. Intra-agency Coordination ....................................................................................................... 7

Chapter 3: Introduction to Distribution Management Plans .................................................... 9

Overview ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………9

Submission ..................................................................................................................................... 9

Guiding Principles ........................................................................................................................... 9

1. Technical Assistance Resources .......................................................................................... 11

Supply Chain Resilience ............................................................................................... 11

Logistics Capability Assistance Tool 2 (LCAT2) .......................................................... 11

FEMA Regional Technical Assistance.......................................................................... 12

2.

Exercising a DM Plan ............................................................................................................ 12

Chapter 4: Components of a Distribution Management Plan ................................................ 14

Overview ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………14

1. Define Requirements ............................................................................................................... 14

1.1 Research Pre-existing Data ......................................................................................... 15

1.2 Conduct Incident-Specific Analysis.............................................................................. 16

1.3 Generic Planning Factors ............................................................................................. 16

1.4 Considerations for Refining the Requirement ............................................................ 16

2. Order Resources ...................................................................................................................... 17

2.1 Existing Internal Capability and Stocks ....................................................................... 18

2.2 Vendor-Managed Inventory (VMI) ................................................................................ 18

1

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

2.3 Partnership ................................................................................................................... 19

2.4 Contracting ................................................................................................................... 19

2.5 Voluntary Organizations Active in a Disaster (VOADs) ............................................... 21

2.6 Faith-based and Community Organizations ................................................................ 21

2.7 Interstate Request Process ......................................................................................... 21

2.8 Donations ...................................................................................................................... 22

2.9 Federal Request Process ............................................................................................. 22

3. Distribution Methods ............................................................................................................ 23

3.1 Direct Distribution ........................................................................................................ 23

3.2 Commodity Points of Distribution (C-PODs) ................................................................ 24

3.3 Transition Plan .............................................................................................................. 26

4. Inventory Management ........................................................................................................ 26

4.1 Resource Tracking ........................................................................................................ 26

5. Transportation ...................................................................................................................... 27

5.1 Modes of Transportation.............................................................................................. 28

5.2 Strategic Considerations .............................................................................................. 29

5.3 Empty Trailer Management ......................................................................................... 30

5.4 Shuttle Fleet ................................................................................................................. 30

5.5 Cross Docking……………………………………………………………………………………………………31

6. Staging ................................................................................................................................. 31

6.1 Models .......................................................................................................................... 33

6.2 Types of Staging Areas ................................................................................................. 35

6.3 Establishing a Staging Site .......................................................................................... 35

6.4 C-POD Operations ......................................................................................................... 37

7. Demobilization...................................................................................................................... 37

7.1 Triggers and Indicators ................................................................................................ 38

7.2 Property Reconciliation ................................................................................................ 38

7.3 Right-Sizing the Mission ............................................................................................... 38

7.4 Organizational Shutdown ............................................................................................. 39

7.5 Reimbursement ............................................................................................................ 39

2

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

7.6 Final Records and Reporting ....................................................................................... 39

7.7 Clean and Replenish Kits ............................................................................................. 39

Appendix A. Acronym List ........................................................................................................ 40

Appendix B: Glossary............................................................................................................... 43

Appendix C. Technical Assistance and Resources ................................................................. 45

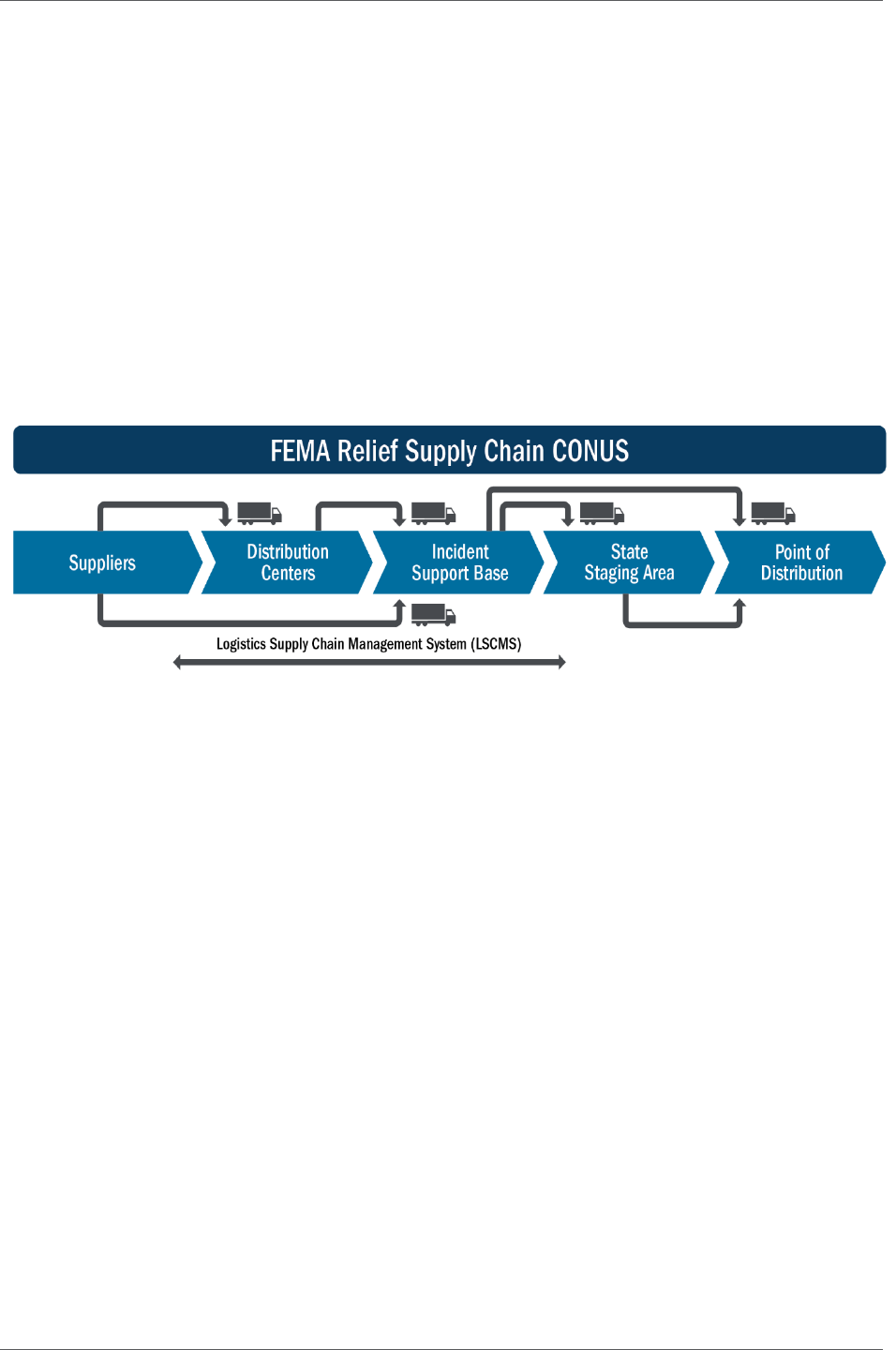

Appendix D. FEMA Relief Supply Chain Map .......................................................................... 47

CONUS ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………47

OCONUS ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………48

Appendix E. Defense Production Act (DPA) ............................................................................. 50

Requesting DPA Priority Ratings .................................................................................................. 50

Establishing a Voluntary Agreement ............................................................................................ 51

Appendix F. Inventory Management Form .............................................................................. 53

INVENTORY MANGEMENT FORM ................................................................................................. 53

Appendix G. Demobilization Checklist .................................................................................... 54

Appendix H. Evaluation Sheet and Review Checklist ............................................................. 56

Distribution Management Plan Guide Review Checklist ............................................................. 58

Appendix I. Distribution Management Plan Template ............................................................ 60

How to use this template .......................................................................................................... 60

Purpose ...................................................................................................................................... 60

Scope ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 61

Overview

.....................................................................................................................................

61

Assumptions

..............................................................................................................................

61

Technical Assistance

.................................................................................................................

62

Components

..............................................................................................................................

63

3

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Chapter 1: Organization

1. Purpose

The

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0 (DMPG 2.0)

provides actionable guidance for state,

local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) agencies, private-sector and nonprofit partners, and the Federal

Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), to effectively and efficiently distribute critical resources to

disaster survivors in the community. Collaboration among these stakeholders supports supply chain

augmentation during a response operation.

The DMPG 2.0 introduces the concept of distribution management, guidance for developing and

maintaining a Distribution Management Plan (DM Plan), and the components of DM Plans. The

organization of the DMPG 2.0 includes:

• Chapter 2: Introduction to Distribution Management

• Chapter 3: Introduction to Distribution Management Plans

• Chapter 4: Components of a Distribution Management Plan

The actions described in the DMPG 2.0 will not necessarily be completed in every incident, nor does

it exhaustively describe every activity that may be required. Local, state, tribal, and territorial officials

and nonprofit and private sector partners must use judgment and discretion to determine the most

appropriate actions at the time of the incident.

2. Background

In 2019, the program requirements for the Emergency Management Performance Grant (EMPG)

were updated to require that recipients’ Emergency Operations Plans include a DM Plan. The DMPG

2.0 provides information on how to develop a DM Plan, the key components of a DM Plan, how to

review and update a DM Plan, and how FEMA reviews and evaluates DM Plans. Lessons learned

during the unprecedented Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, 2019 and 2020 hurricane seasons,

and recent wildfires illustrated the complexity of planning for and establishing temporary distribution

management systems that can rapidly source, track, transport, stage, and distribute critical

emergency supplies to disaster survivors.

3. Supersession

The DMPG 2.0 replaces the existing Distribution Management Plan Guide published in 2019. The

revised DMPG incorporates lessons learned and best practices from recent response operations and

provides new tools to assist with distribution management.

4

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

4. Document Management and Maintenance

The FEMA Office of Response and Recovery (ORR), Office of Doctrine and Policy is responsible for the

management and maintenance of this document. Comments and feedback from FEMA personnel

and stakeholders regarding this document should be directed to the Office of Policy and Doctrine at

FEMA HQ at FEMA-ORR-Doctrine@FEMA.DHS.gov.

5

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Chapter 2: Introduction to

Distribution Management

This chapter describes the concept of distribution management and the various coordination

opportunities that exist to share information and engage SLTTs.

Overview

Distribution management is an activity that encompasses all organizations, processes, systems, and

tools used to move commodities from one location to another to quickly deliver resources to disaster

survivors. Large-scale disasters often disrupt normal supply chains, triggering the need for temporary

relief supply chains that address critical emergency supplies such as food, water, and fuel. This

temporary distribution management system is managed by SLTT agencies or voluntary, faith-based,

or community-based organizations. Distribution management at the SLTT level includes:

End-to-end commodity and resource management.

Warehouse and transportation operations to effectively and efficiently distribute supplies to

staging areas and distribution points.

Provision of equipment and services to support operational requirements.

A mechanism for supplies and commodities to be provided to survivors.

As with disaster response, distribution management is locally executed, state-managed, and

federally supported. SLTT governments play a large role in establishing and maintaining logistics

capacity to effectively manage and employ FEMA resources.

The distribution management function is used to move commodities and resources to prepare for,

respond to, recover from, and mitigate the effects of an incident; enable restoration of private sector

distribution; and supplement or augment a relief supply chain. FEMA’s distribution management

function supports SLTTs in closing gaps and building capabilities. At the Federal level, distribution

management includes:

Managing a comprehensive relief supply chain, including warehouse operations where FEMA

receives, stores, and issues commodities and equipment; and transportation operations to

effectively distribute supplies, equipment, and services in response to domestic disasters

and emergencies.

Establishing commercial contracts and agreements with multiple public and private sector

partners to provide additional support.

Setting up incident support bases and federal staging areas to quickly deliver resources to

disaster survivors.

6

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Coordinating situational awareness of disaster impacts to supply chain networks to aid in

developing interventions to expedite restoration of private sector distribution and target

emergency management efforts.

FEMA's DMPG 2.0 enables unity of effort among resource coordination and movement from the

incident, regional, and national levels.

1. Intra-agency Coordination

FEMA’s Logistics Management Directorate (LMD) collaborates extensively with other FEMA

components to provide opportunities for SLTT engagement and information sharing. Through this

process, FEMA components provide technical expertise and logistical support for EMPG recipients.

Table 1 highlights examples of types of support between LMD and other FEMA components at

different points during the distribution management process.

Table 1. Examples of Intra-agency Distribution Management Coordination

FEMA Component Coordination Opportunities

FEMA Regions

Provides technical assistance to improve emergency

management capabilities. This technical assistance includes in-

person workshops and opportunities for peer-to-peer learning

on emerging, cross-cutting, or complex topics.

FEMA Integration Teams

(FIT)

Provides technical and training assistance on the Federal

Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) programs and

continuous on-site support to the state. FIT represents FEMA’s

commitment to reducing the complexity of FEMA programs

through direct staff engagement on emergency management

with the state.

Office of Business,

Supports coordination with private sector partners and

Industry, and

resources.

Infrastructure

Supports lifeline stabilization and access to critical services.

Integration (OB3I)

Provides situational awareness of ongoing efforts to engage the

private sector through the National Business Emergency

Operations Center.

Cultivates and advocates for private sector integration with

FEMA and SLTTs.

Field Operations

Coordinates effective and efficient availability and deployments

Directorate (FOD)

to ensure FEMA is able to help people before, during, and after

disasters.

Organizes the incident workforce and provides field leadership.

Ensures training and qualifications of the incident workforce,

7

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

FEMA Component Coordination Opportunities

National Exercise

Provides exercise assistance to Regions, to help state, local,

Division (NED)

tribal and territorial (SLTT) partners in designing, developing,

and exercising exercises to test Distribution Management Plans

(DM Plans).

National Integration

Provides planning technical assistance, to include supply chain

Center (NIC)

collaborative technical assistance that helps local emergency

managers explore and understand supply chains and support

private-public collaboration for catastrophic incidents.

Office of the Chief

Counsel (OCC)

Provides subject matter expertise for creating memorandums

of understanding (MOU).

Office of the Chief

Procurement Officer

(OCPO)

Coordinates with contracted private sector partners.

Office of External Affairs

(OEA)

Develops appropriate messaging to answer stakeholder and

media questions around distribution plans happening in

responses.

Recovery Directorate

Supports recovery support function (RSF) operations.

Promotes resource capabilities identified by SLTT and private

sector partners.

Promotes increased situational awareness through established

communications channels with SLTT and private sector

partners.

Coordinates with Disaster Survivor Assistance (DSA) to address

the needs of disproportionately impacted populations and

disaster survivors.

Response Directorate

Provides expertise on distribution management needs and

capabilities to support lifeline stabilization.

Office of Policy and Provides support to direct Defense Production Act (DPA)

Program Analysis (OPPA) resources.

Provides support to identify partners interested in the DPA.

Provides support for updating LMD policies and strategies.

8

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Chapter 3: Introduction to

Distribution Management Plans

This chapter contains an introduction to DM Plans, including the guiding principles for development.

These tools assist SLTTs and their partners to better understand the needs and gaps of their

communities to create a more effective DM Plan.

Overview

A DM Plan establishes strategies, functional plans, and tactical guidance for SLTT logistical response

operations. These plans cover staging sites and operations, logistical support services and

personnel, information management, transportation of resources to point of need, commodity points

of distribution (C-PODs), inventory management, resource sourcing, and demobilization.

DM Plans include sections with information on the following seven components:

1. Define Requirements

2. Order Resources

3. Distribution Methods

4. Inventory Management

5. Transportation

6. Staging

7. Demobilization

Submission

Per the 2021 Preparedness Grants Manual, EMPG recipients are required to submit their DM Plan to

the Regional Grants Office along with the Q3 (quarter ending September 30) Periodic Performance

Report (PPR) of their most recent EMPG award. The Regional Grants Office coordinates with Regional

Logistics Staff to review and evaluate the DM Plan using the standard criteria in Appendix H. Regions

provide recipients with additional feedback and technical assistance as necessary to ensure

continual progress and improvement of the DM Plan for the next annual submission.

Guiding Principles

Guiding principles for DM Plan development enable SLTT partners to strengthen capabilities before a

disaster, which enhances the effectiveness of resource distribution to survivors after a disaster.

9

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Having distribution procedures ready minimizes the time required to distribute commodities to

survivors. When developing a DM Plan, consider the guiding principles outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. Guiding Principles for Distribution Management Plan Development

Guiding Principles for

Distribution

Management Plan

Development

Description

Remain SLTT focused

State, local, tribal and territorial (SLTT)-led distribution

management provides clear direction and expected outcomes.

Emergency management is locally executed, state managed,

and federally supported when requested and appropriate.

Collaborate with the

Partnership between SLTT partners, private sector, the

whole community

Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC), and

nonprofits can bridge gaps until normal supply chain systems

are restored. Improved communication among all responsible

parties mitigates the risk of artificial demand and ensures that

the jurisdictions place teams and critical commodities in areas

that support survivors and communities. Involving the whole

community will most effectively re-establish the normal supply

chains, minimizing the dependence for relief supply chains.

Equity for underserved

Work with whole community partners to identify resource gaps

communities

for underserved and historically marginalized people.

Develop strategies for making sure critical commodities and

resources are distributed equitably.

Explore and develop

Consider implementing new ways to establish Commodity

best practices to get

Points of Distribution (C-PODs), identify ingress and egress

resources directly to

routes, and leverage traffic patterns.

survivors

Develop innovative messaging to inform the public of resource

locations.

Identify isolated populations and develop creative solutions to

deliver supplies.

Develop innovative and accessible messaging to inform the

public of resource locations.

Identify gaps and

Consider conducting a risk analysis within each DM Plan

shortfalls

component to identify gaps and shortfalls that may emerge

during an incident.

Analyze emerging risks from climate change that are causing

larger and more frequent disaster incidents.

10

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

1. Technical Assistance Resources

Several resources and tools already exist to help develop a DM Plan. These include the Supply Chain

Resilience Guide and the Logistics Capability Assistance Tool 2 (LCAT2). Additionally, specific

functional guides cover staging operations, transportation management, C-POD operations, inventory

management, and tracking and acquisition are also available.

Appendix C provides a complete list of

available resources and technical assistance.

Supply Chain Resilience

FEMA’s Supply Chain Resilience Guide provides emergency managers and planners at every level

with a basic introduction to supply chains. Supply chain resilience is key to disaster response.

Successful SLTT distribution management planning depends on a clear understanding of pre-

incident private sector supply chain norms and flows. If emergency managers understand

fundamental network behaviors, they can help avoid unintentional suppression and create

intentional enhancement of supply chain resilience.

Supply Chain

The socio-technical network that identifies, targets, and fulfills demand. It is the process of

deciding what, when, and how much should move to where.

Source: FEMA Supply Chain Resilience Guide

Understanding a jurisdiction’s supply chain can have a great impact on emergency plans and

planning. The Supply Chain Resilience Guide helps emergency managers think through the

challenges and opportunities presented by supply chain resilience and provides specific suggestions

on research, accessible outreach, and action.

SLTT emergency managers use the FEMA Supply Chain Resilience Guide to map, analyze, conduct

outreach, take appropriate actions, and assess and refine private sector supply chain resilience

activities. DM Plans should not detract from or impede recovery of surviving private sector capability.

The relief supply chain efforts and supporting distribution plan should focus on filling the gaps in the

private sector supply chains.

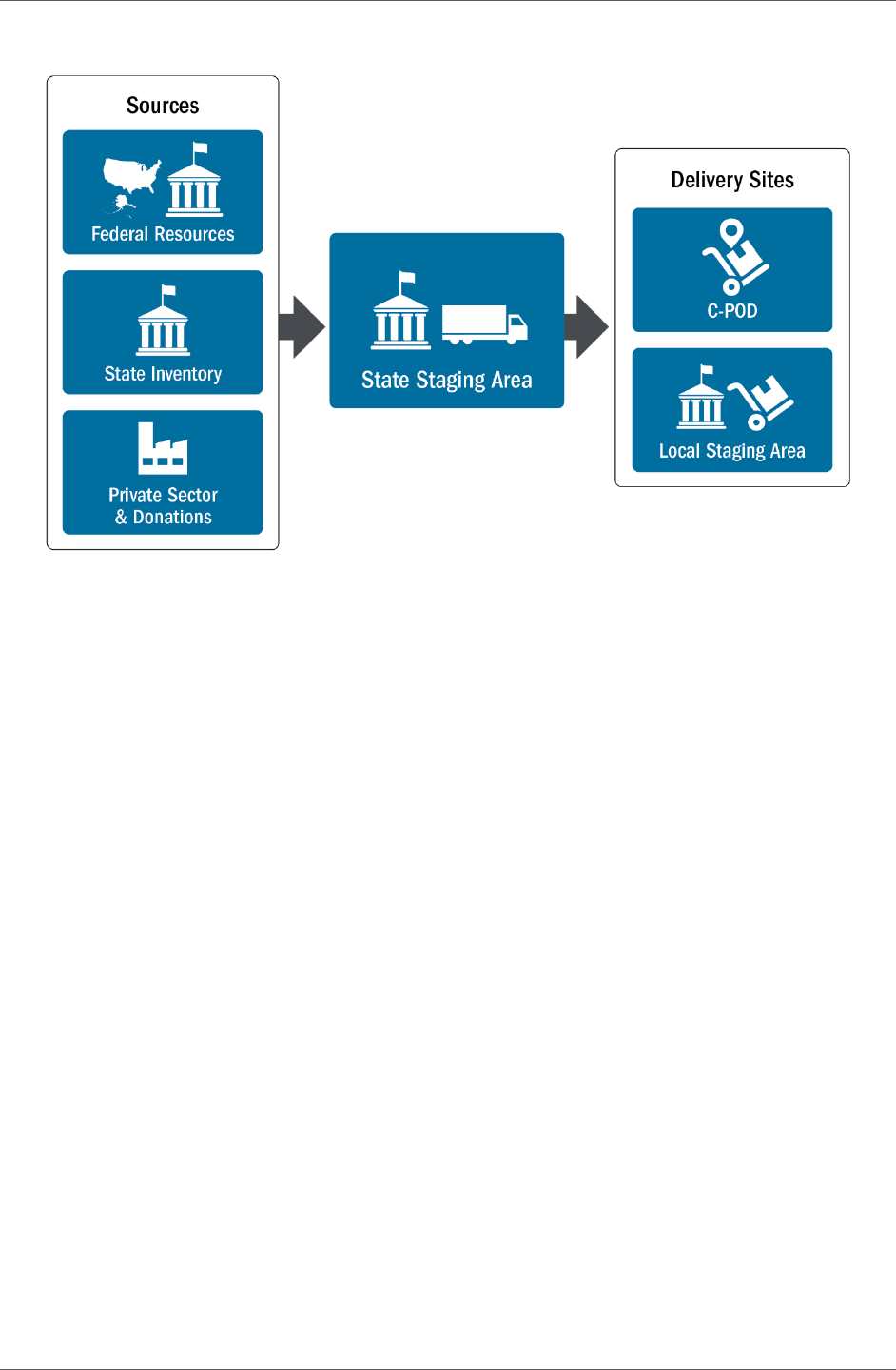

Appendix D provides an example of the relief supply chain.

Logistics Capability Assistance Tool 2 (LCAT2)

The LCAT2 is a transferrable tool for use by SLTT governments that encourages collaboration among

multiple stakeholders to assess core logistics functions, identify strengths and relative weaknesses,

and focus efforts for continued improvement within disaster response logistics. The LCAT2 was

designed by FEMA logistics experts to provide SLTT emergency managers with a comprehensive

understanding of their logistics capabilities. LCAT2 is formatted as an Excel file within a web-based

program that prompts a series of questions. The tool aggregate answers to produce a set of graphs

that identify logistics strengths and opportunities for improvement.

11

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

SLTT governments have the option to participate in LCAT2 workshops. These workshops average 1.5-

2 days in length and are held in person or virtually. Workshops are led by a facilitation team that

includes staff from FEMA Regions Logistics Support and FEMA Headquarters ORR/Logistics Plans.

Upon completion of the workshop, a FEMA team will assist with all administrative support and

provide a confidential written Analysis Report based upon the assessment conducted during the

workshop. The Analysis Report details the validated measurement criteria that the SLTT submitted

during the assessment, which evaluated the SLTT’s overall logistics capabilities in the preparedness

and response and recovery areas. The Analysis Report documents a better understanding of the

SLTT’s readiness to respond to disasters, assesses strengths and weaknesses, and identifies areas

for improvement.

The LCAT2 enables an unbiased assessment of the SLTT logistics capabilities, by:

Evaluating current SLTT disaster logistics readiness.

Identifying areas for targeted improvement.

Developing a roadmap to mitigate weaknesses and further enhance strengths.

For more information on the LCAT2, contact your FEMA Regional Logistics Branch Chief.

FEMA Regional Technical Assistance

FEMA Regions support SLTTs through various forms of technical assistance including, periodic

engagement sessions to discuss DM Plan requirements, logistical support, in-person workshops, and

opportunities for peer-to-peer learning on emerging, cross-cutting, or complex topics.

For example, Region IV conducts monthly logistics calls and focus groups with states to discuss

challenges in a group setting. Although solutions are often state specific, the goal is to create or

identify shared solutions that can be captured in DM Plan development.

Other forms of technical assistance include reviewing past After-Action Reports (AAR) from previous

incidents to incorporate best practices and/or assigning a Lead Logistics Planner to each state or

territory.

2. Exercising a DM Plan

Exercises help build preparedness for threats and hazards by providing a low-risk, cost-effective

environment to test and validate plans, policies, procedures, processes, and capabilities. Exercises

also enable participants to identify resource requirements, capability and accessibility gaps,

strengths, areas for improvement, and best practices. Conducting exercises provide SLTTs with an

opportunity to test and validate their DM Plans. FEMA offers design, development, facilitation, and

evaluation support for individual exercises to SLTT and other whole community partners.

12

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Exercising DM Plans creates an opportunity for SLTTs to determine how effective the plan is, identify

any gaps, and validate if the DM Plan is realistic enough to implement. Best practices for designing

an exercise to test DM Plans include:

Conducting workshops and facilitated discussions on how to create and validate DM Plans

and training, review existing plans, and discuss ways to improve the DM Plan

Coordinating with FEMA Integration Team (FIT) personnel

Incorporating the use of private sector resources

Providing DM Plan samples and examples to support DM Plan development

Joint Full-Scale Exercise: State of Ohio and FEMA

The State of Ohio has exercised side by side with FEMA in the full-scale exercise Eagle

Rising to Point of Distribution Operations downstream of a Federal Staging Area practicing

the receipt of commodities and establishment of burn rates. The state invited FEMA

regional logistics to observe State Staging Areas exercising with public-private partnerships

to supply local PODs.

Collaborating with the National Guard

Louisiana conducts statewide Point of Distribution (POD) exercises to train the Louisiana

National Guard (LANG) on how to operate both a POD and the state component of the supply

chain, in a robust and effective manner. LANG controls the state’s supply chain as it relates to C-

PODs, staging areas, and distribution management. LANG has organic capability to develop and

execute annual exercises and conduct internal training to prepare units for upcoming hurricane

seasons.

Figure 1. C-POD Layout

13

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Chapter 4: Components of a

Distribution Management Plan

This chapter provides detailed information on the main components of a Distribution Management

Plan.

Overview

This section provides detail on the seven components of a DM Plan:

1) Define Requirements

2) Order Resources

3) Distribution Methods

4) Inventory Management

5) Transportation

6) Staging

7) Demobilization

1. Define Requirements

Some requirements can be identified prior to an incident based on the jurisdiction’s hazard analysis,

previous situations and operations, demographic profiles, communities’ data, and modeling.

Planning models and matrices help determine the resources necessary to assist affected

populations.

Resource requirements may exceed a jurisdiction’s capability to manage resource distribution. A

best practice is to order the number of resources that align with a jurisdiction’s ability to store and

distribute them because sending too many resources into a disaster area can hamper the response.

While generic planning factors may be used initially, jurisdictions should refine the requirement

based on demand for meals, water, mass care supplies, transportation of the resources, and an

understanding of private sector capacity and capabilities.

To ensure response efforts do not impede rapid recovery, engaging with the private sector helps

understand the established baseline (blue sky) norms, pre-disaster supply chain flow, and how

disasters impede this flow.

14

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

SLTT agencies can leverage data sets such as FEMA’s LCAT2 to identify potential requirement needs.

Additionally, the DM Plan evaluation criteria can serve as a checklist for meeting plan requirements.

For example, following the severe winter storm in 2021, Texas worked with Region VI to review what

occurred during the winter storms versus what was outlined in the state’s DM Plan. This opportunity

allowed Texas to examine transportation shortfalls, major chokepoints, and secondary sites

selections.

1.1 Research Pre-existing Data

A critical first step in developing a robust distribution plan is to conduct an unbiased assessment of

the SLTT logistics capabilities. For example, leveraging the Department of Homeland Security’s

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s (CISA) supply chain vulnerability assessments and

the Supply Chain Analysis Network (SCAN) can help to identify potential challenges in distribution

planning.

The following sources and tools, although not required, provide mechanisms to research and collect

pre-existing data:

LCAT2: LCAT2 helps SLTT organizations conduct self-assessments to determine their

readiness to respond to disasters. The survey-style tool provides a detailed assessment of

core logistics functions, helps jurisdictions identify specific strengths and weaknesses, and

constructs a systematic roadmap for SLTTs to improve current logistics processes and

procedures.

Deliberative Plans and Historical Data: Models or scientific data for planning factors may

already be used by your jurisdiction; these agreed-upon factors provide realistic information

for resource requirements. Data models and planning factors should account for the

emerging risks of climate change which amplifies the impacts of annual planning threats.

Reviewing previous distribution and burn rates, after-action reports, and lessons learned

reports may provide insight to developing resource requirements.

Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA): The THIRA helps

communities understand their risks and determine the level of capability that they need to

address those risks. The outputs of this process lay the foundation for determining a

community’s capability gaps as part of the Stakeholder Preparedness Review.

Comprehensive Preparedness Guide (CPG) 201 provides guidance for conducting a THIRA

and Stakeholder Preparedness Review.

Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (HIRA): A HIRA provides the factual basis for

activities proposed in the strategy portion of a hazard mitigation plan. An effective risk

assessment informs proposed actions by focusing attention and resources on the greatest

risks. The four basic components of a risk assessment are 1) hazard identification, 2)

profiling of hazards, 3) inventory of assets, and 4) estimation of potential human and

economic losses based on the exposure and vulnerability of people, buildings, and

infrastructure. For more detailed guidance on the process to complete a multi-hazard risk

assessment, work with your State Hazard Mitigation Officer or see FEMA’s State Mitigation

15

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Plan Review Guide, Tribal Mitigation Plan Review Guide, Local Mitigation Plan Review Guide,

or Local Mitigation Planning Handbook.

Regional Resiliency Assessment Program (RRAP): Managed by the Department of Homeland

Security (DHS), the RRAP is a voluntary, non-regulated interagency assessment of critical

infrastructure resiliency in a designated geographic region. Each year DHS, with input and

guidance from Federal and state partners, selects several projects for the RRAP that focus

on specific infrastructure sectors within defined geographic areas and address all-hazard

threats that could result in regionally and/or nationally significant consequences.

FEMA Flood Map Service Center (MSC): The FEMA Flood Map Service Center (MSC) is the

official public source for flood hazard information produced in support of the National Flood

Insurance Program (NFIP). Use the map service enter to find official flood map, access a

range of other flood hazard products, and take advantage of tools for better understanding

flood risk.

County, Municipality, or Parish Profiles: County, municipality, and parish profiles are a

compilation of selected economic, geographic, and demographic data that can be utilized to

determine resource needs. These profiles typically provide a statistical snapshot of

information related to development tracking, employment, transportation, and community

resources.

1.2 Conduct Incident-Specific Analysis

Based on demographics and impacted populations, the initial distribution network should effectively

support and distribute resources to survivors in the jurisdiction. An overall 72 or 96-hour

requirement drives the scale and scope of the SLTT staging areas, transportation requirements, and

C-PODs. Jurisdictions develop initial distribution network requirements by using the pre-existing data

and various tools to conduct incident-specific analysis. Some tools include the private

sector/Business Emergency Operation Centers (BEOCs), modeling tools, and geo-enabled tools (e.g.,

geographic information system [GIS]).

1.3 Generic Planning Factors

If deliberate plans are not available, generic FEMA planning factors of two meals and three liters of

water per person of the impacted population each day can be used. Customize the planning factors

based on impact population (e.g., 10, 20, or 75 percent) relative to the characteristics and/or

intensity of the incident (e.g., hurricane, earthquake, flood). Other FEMA generic planning factors can

be coordinated through the Regional Logistics Section and Recovery.

1.4 Considerations for Refining the Requirement

Additional considerations that make sense for the community should be used to adjust the planning

factors used in developing requirements. Each jurisdiction needs to look at their historical and

current data if any exists. For example, population zones and storm strengths can alter generic

planning considerations.

16

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

In addition to the considerations listed below, other types of resources that may be considered for

distribution include propane, gas stoves, flashlights, blankets, and bug spray.

Meals: Incorporate community preferences (e.g., cultural, dietary, age) within reason and

practicality into the type of meals stocked and ordered. For example, if your community has a

large population that culturally eats a specific food, then the plan should include reasonable

storage and procurement capabilities for that specific food.

Water: As units of measure (e.g., gallons, liters) vary, develop consistent language in

planning, ordering, and reporting processes to reduce confusion among stakeholders.

Suggest using liters as the standard unit of measure, as that is FEMA’s standard. When

determining how much bottled water to distribute, consider other available sources of

potable water and identify efforts (e.g., installation of generators at water plants) that could

be taken to back up local water systems.

Mass Care Supplies: These are unique to each incident. Some commonly used supplies

include shelter items (e.g., cots, blankets), among others (e.g., camp stove, lanterns,

flashlights). Consulting community data can inform supply requirements, such as

accessibility requirements.

Support/Transportation: The geography of the jurisdiction may drive diverse transportation

strategies and requirements (e.g., ground, air, sea).

Capability and Capacity of Distribution Network: Identify what is possible for the jurisdiction

during the planning stage and understand the limitations of the disaster supply chain nodes.

The number of resources ordered should not exceed the distribution network’s capacity (e.g.,

the maximum storage and throughput capabilities of the on-ground staging areas and C

PODs).

Private Sector Capability versus Requirement: Revise planning factors based on

understanding the status of private sector supply chains, time to restoration, and how this

will impact the duration of the requirement for critical emergency supplies. Monitor the

private sector’s ability to re-establish its supply chain, which may reduce the response

requirements for emergency commodities and resources. Leverage the private sector to

assist with the response (e.g., transportation, supplies, food, water).

Climate Change Impacts: Challenges posed by climate change, such as more intense storms,

frequent heavy precipitation, heat waves, drought, extreme flooding and higher sea levels

could significantly alter the types and magnitudes of hazards faced by communities. More

intense disasters could impact distribution of resources and delivery methods. Consider the

impacts of climate change on distribution planning assumptions.

2. Order Resources

Sourcing resources relies on establishing organic capabilities and capacity to provide commodities

and equipment to disaster survivors based on the pre-identified jurisdictional requirements.

Establishing multiple sourcing mechanisms mitigates supply chain risk. Thus, building existing

17

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

internal capability and stocks is paramount to effective distribution management. For example,

SLTTs can establish standing, spot, or contingency contracts for resources, vendor-managed

inventory (VMI), logistics services, warehousing, and coordinating with nonprofit and other

government partners (e.g., Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster [VOADs], Emergency

Management Assistance Compact [EMAC], etc.).

Engaging and leveraging a whole community approach initiates an effective and beneficial path of

success in implementing a DM Plan. This approach creates an informed and shared understanding

of community needs and capabilities, greater empowerment and integration of resources from

across the community, establishment of relationships that facilitate more effective response and

recovery activities, and a stronger and greater resiliency at the community level. Partnerships with

residents, local businesses and agencies, EMAC, private sector personnel, and Federal government

agencies allows for consistent coverage across all levels of response and a decrease in the chance

for gaps in resource delivery and recovery.

Use of the Defense Production Act

In response to the COVID-19 global crisis, the Defense Production Act (DPA) was used by the

presidential authority to expedite and expand the supply of materials and services from the

United States industrial base. DPA authorities are available to support: Emergency

preparedness activities conducted pursuant to Title VI of the Stafford Act; protection or

restoration of critical infrastructure; and efforts to prevent, reduce vulnerability to, minimize

damage from, and recover from acts of terrorism within the United States. See Appendix E for

additional information.

The following sources of supply are listed in a suggested order of consideration that supports the

optimal framework (where emergency management is locally executed, state managed, and federally

supported).

2.1 Existing Internal Capability and Stocks

A standing inventory of critical emergency supplies can be drawn upon in response to an incident;

this is a logical first source for meeting immediate needs of a time-sensitive nature. This standing

inventory may include items such as medical supplies or commodities (e.g., meals and water).

Leveraging the capacity of other stakeholders can bolster the SLTT jurisdiction’s ability to support

logistical requirements (e.g., schools, universities, meals on wheels).

2.2 Vendor-Managed Inventory (VMI)

Vendor Management Inventory (VMI) is a network of business models in which the buyer of a product

provides certain information to a supplier of that product (vendor), and the supplier takes full

responsibility for maintaining an agreed-upon inventory of the material.

18

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

On occasion, vendors may hold a portion of inventory in their warehouses to more effectively rotate

stock, though they may charge associated holding costs, regardless of the rate of consumption.

Although this method is available, it may be less cost effective to house and stock your own

warehouse.

VMI can be utilized during small and large-scale disasters allowing SLTTs to defer manpower,

resources, and response efforts to different parts of an incident.

Using Vendor Managed Inventory (VMI)

The State of Indiana uses VMI to store meals and water in the Marengo caves. Vendors can

manage shelf life by obtaining state permission to rotate product toward other customer disaster

needs, later backfilling the items drawn from inventory saving replenishment costs.

2.3 Partnership

Partnerships require an understanding of steady-state operations and available capabilities. For

example, consider identifying SLTT institutions that order and buy meals and water regularly, such as

schools and universities, correctional facilities, and other community infrastructures.

2.4 Contracting

The optimal time to prepare contracts is before an incident occurs. This includes assessing

capabilities during steady-state and anticipating potential resource requirements to determine

contracting needs. Know the key vendors, suppliers, and manufacturers that can provide the needed

capability. Contracts can address needs for the following resources and capabilities:

Life-sustaining commodities (e.g., water, meals, cots, blankets, tarps).

Critical emergency supplies (e.g., generators, fuel, sandbags, pumps).

Transportation (e.g., air, sea, ground, multimodal).

Third-party logistics (e.g., warehouse management, inventory tracking).

Some additional considerations when preparing contracts include the following:

Legislation: Consider whether applicable laws and regulations governing procurement may

permit or hinder standing contracts with private vendors for commodities and/or logistics

services, early commodity acquisition, and warehousing. Contingency contracts established

prior to an incident may accelerate response time. Also, spot contracts may be required in a

relatively short period of time to source immediate needs. Pre-scripting a statement of work

for anticipated requirements can help jurisdictions move quickly to establish a new contract.

Existing Contracts: Inventory existing jurisdictional contracting vehicles and business

capability in advance of an incident. Ensure logistics personnel understand the established

supply chains and vehicles. Adding capacity to an existing contract can accelerate ordering.

19

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Staffing: In most cases, existing purchasing capability and authorized offices for purchasing

and contracting will be leveraged. During disaster response, staff must be flexible and have a

sense of urgency, allowing jurisdictions to scale operations with an adequate number of

trained personnel. Consider which personnel have the requisite contracting skills, which

agencies staff may be drawn from, or what agencies may need to be assigned this role. As

with other aspects of emergency management, it is important to practice actions planned

and validate staff capability.

Vendor Deconfliction: Cross-walking suppliers with neighboring counties, municipalities,

parishes, SLTT agencies, and Federal partners ensures that you have different vendors and

suppliers. Confirm that vendors committed to multiple entities have the capacity to service all

commitments simultaneously.

Redundancy: Establishing relationships and vehicles with multiple vendors is useful as a

contingency. Multiple options eliminate the dangers of single-point failure, making the supply

chain more resilient.

Purchase Cards: Each jurisdiction establishes unique requirements on who can use

government purchase cards, for what purpose, and any thresholds on spending.

Understanding these limitations and knowing these parameters in advance ensures

purchase cards are clear for end users.

Exercises: SLTT governments should hold periodic exercise or training sessions with their

contractors. Contractors may need to be available 24/7 before and during disasters.

Exercises help clarify the requirements and the urgency of disaster responses, equipping

contractors to be readily available when every hour is critical.

States are able to use existing Federal contract schedules during an emergency, such as the General

Services Administration's (GSA) Disaster Purchasing Program. Other national programs are available

through the Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS),

and other Federal agencies. [Note: this is separate from Direct Federal Assistance that becomes

available during a declared disaster with a cost-share where applicable.]

When considering these tools, be cognizant of speed and cost. They cannot replace effective market

research or existing capabilities.

2.4.1 SECONDARY CONTRACTING

Certain supply nodes may be overseas, across the country, or in hazardous areas and could have

potential incidents that impact supplier production (e.g., extreme weather or natural disasters,

political upheaval, national holidays). Establishing secondary contracts with alternative suppliers

would ensure the acquirement and delivery of resources in situations where primary contracts may

not have the necessary amount or capability to provide supplies.

20

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

2.5 Voluntary Organizations Active in a Disaster (VOADs)

Establishing a relationship with national and state VOAD members to harness effective and targeted

operations can help deliver critical emergency supplies to disaster survivors. A state VOAD

representative needs a seat in the state Emergency Operations Center (EOC) to coordinate with the

liaison officer. For more information on national and state VOAD contacts, visit the National VOAD

website.

2.6 Faith-based and Community Organizations

Faith-based and community organizations offer a wide variety of human and material resources that

can prove invaluable during and after a disaster has occurred. These organizations can be points of

distribution for emergency commodities and supplies, provide staging areas and reception sites for

emergency services, and/or support mobile feeding and transportation services. Many faith-based

and community organizations are connected to the national and state VOADs and engage in disaster

activities in preparedness and during operations. For more information on engaging these

organizations, see the Engaging Faith-based and Community Organizations Planning Considerations

for Emergency Managers guide.

2.7 Interstate Request Process

Through EMAC, states can support each other with resources, commodities, teams, or services.

EMAC enables assistance during governor-declared states of emergency or disaster through a

responsive, straightforward system that allows states to send personnel, equipment, and

commodities to assist with response and recovery efforts in other states. Determine what resources

and capabilities (e.g., equipment, transportation, lodging, warehouse) are available for the state to

use and are needed to deploy staff.

Figure 1. EMAC Activation Process

21

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

2.8 Donations

Donations can be of national or international origin. International donations can come to an SLTT

jurisdiction via two different routes and are handled differently.

For international donations provided directly to the SLTT partners, collaboration with the

Department of State, Customs and Border Protection, and appropriate regulatory agencies is

necessary.

FEMA may accept international donations in support of survivors and will work directly with

SLTT partners to facilitate rapid acceptance and distribution as necessary. In general, FEMA

does not accept and warehouse donations in its supply chain.

Direct donations to FEMA will be managed by FEMA International Affairs Division (IAD) to the

maximum benefit of the SLTT partners. IAD works to promote international coordination to

establish and maintain partnerships with capable international responders and implement

arrangements for cross-border mutual assistance to build a more resilient Nation

SLTT partners should consider their donation strategy for disaster operations, especially for

unsolicited donations. Coordinate with communications or media teams on messaging, specifically

on the donation requirements, pickup/drop-off logistics, private sector donations,

storage/warehouse/equipment needed, solicited/unsolicited donation practices, and direct

deployment. The Department of State can ensure this information is disseminated globally,

minimizing negative impacts to the logistics supply chain.

FEMA can provide technical assistance for donations, such as the layout of the warehouse

management plan or leasing of the warehouse or equipment.

2.9 Federal Request Process

When a state exhausts its resources, it turns to FEMA for assistance. A state may make an official

request for direct Federal assistance once a presidential emergency or disaster declaration has been

issued for that state. This request must be submitted to FEMA through the Agency’s web-based

Emergency Operation Center (WebEOC), on an official document known as the Resource Request

Form (RRF).

A state may request technical assistance at any time regardless of declaration status. Aligning state

processes with FEMA processes for Federal resource requests streamlines resource delivery directly

to survivors.

22

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Figure 2. Federal Request Process

3. Distribution Methods

Methods of distribution describe how commodities are provided directly to the impacted

communities. The planned distribution includes robust yet scalable methods to accommodate any

level of disaster and support the characteristics of the affected communities. Two common methods

include:

Direct distribution: Supplies are initially moved to a central location for staff to collect and

redistribute through “door-to-door” residential delivery.

Commodity Points of Distribution (C-PODs): Initial (accessible) point(s) where survivors can

obtain emergency relief supplies. C-PODs can be in accessible open areas or existing

community infrastructures (e.g., schools, athletic facilities, community centers) or accessible

care facilities (e.g., shelters, food banks, cooling/warming stations, feeding kitchens).

The following sections discuss each of these methods in greater detail.

3.1 Direct Distribution

Supplies can be delivered directly to a survivor’s residence through direct distribution. Supplies may

be initially delivered to a central location for personnel to provide “door-to-door” residential delivery.

First, consider the populations that need to be served (e.g., people with disabilities, highly dispersed

populations or populations with no means to travel that may live in nursing homes, hospitals, or

remote homes). Then identify ways to reach these populations, including equipment, types of

delivery vehicles, and cross-docking needs. Implementing these mechanisms may require identifying

and partnering with the following existing community organizations or activities:

Health and Welfare Checks: Leverage these checks to enable employees to deliver supplies.

National Guard: Enable military members to deliver supplies when conducting house-to-

house visits.

Mass Care: Leverage multiple delivery mechanisms:

○ Contract for food resources (e.g., grocery boxes)

23

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

○ Coordinate delivery of resources at their facilities (e.g., shelters, food banks,

cooling/warming stations, feeding kitchens, and responders [e.g., search and rescue

teams, state police, EMTs])

○ Collaborate with Meals on Wheels, Food Banks, and School Districts.

Marinas and Private Airports: Understand their steady-state capabilities and coordinate

requirements for use of special vehicles (e.g., vulnerable populations, high-water, rotary-wing,

boats, trains, all-terrain) for distributing resources to isolated communities.

Mobile Delivery: Use their vehicles to drive into an affected area and provide commodities at

different drop locations or where the need is identified. This type of distribution is common in

rural areas and where roads are damaged.

3.2 Commodity Points of Distribution (C-PODs)

A C-POD establishes an initial accessible point(s) where the public can obtain life-sustaining

emergency relief supplies. These facilities must serve the population until no longer needed; this

may be indicated when power is restored, traditional facilities reopen (e.g., retail establishments),

fixed and mobile feeding sites and routes are established, and/or relief social service programs are

in place.

The following subsections discuss considerations for establishing C-PODs.

3.2.1 TRAINING

FEMA offers comprehensive C-POD training to help develop actionable plans for emergency

distribution and understanding associated challenges. The IS-26: Guide to Points of Distribution

Course, including an explanatory DVD, C-POD guide, and online exam, is available on the Emergency

Management Institute (EMI) website.

Additional training measures include train-the-trainer courses to customize C-POD training for

jurisdictions within SLTT governments and conducting full-scale exercises that test C-POD’s

capability. When providing training, it is important to include all participating groups and

organizations that would be activated upon implementation of a DM Plan. These participating groups

can include the National Guard, local emergency responders, volunteer organizations, and

Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) members. Incorporating these groups into training

exercises generates a full understanding of their roles and responsibilities during an incident and

how they fit into the DM Plan at large. This requires the need for training materials that are

accessible for people with disabilities as well as available for people with particular language needs.

In addition to traditional C-POD training and the above alternatives, initiating a Regional Logistics

SLTT Outreach Program allows for each state to identify critical counties, municipalities, or parishes

for their most common hazard(s).

24

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

3.2.2 MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS

Regardless of the methods used, the DM Plan should be feasible—within the capabilities, limitations,

restraints of the community being served—and include the following information:

The site location(s).

Individuals or groups responsible for managing the C-PODs (e.g., National Guard, SLTT

employees, volunteers, schools); may include the Adopt-a-POD model.

Equipment resourcing methods.

Operations (e.g., hours of operation, reporting, safety, accountability, basis of issue, security,

commodities to be disbursed).

Demobilization plan (more information in Section 7. Demobilization.).

Accountability and management of empty trailers.

Reporting system and reporter(s).

C-POD wraparound support contracts (e.g., portable toilets, light tower maintenance and

fueling, security, solid waste removal).

3.2.3 OPERATIONS

Within the C-POD operations section of the DM Plan, consider alternate methods (e.g., Adopt-a-POD,

pop-up PODs, churches, VOADs, businesses) and their impact on the disbursement of commodities

(e.g., burn rate, accessibility requirements). Address how response logistics leverage pop-up PODs

and VOAD kitchen operations. Every food bank system has a feeding distribution plan that should be

capitalized on. Develop a good working relationship with these groups to quickly expand a

distribution network in a disaster environment.

3.2.4 URBAN OPERATIONS

C-POD operations differ in an urban environment, which might include cross-docking, foot traffic, and

public transportation aspects. Find the existing infrastructure of community hubs that are easily

accessible, especially by foot, to establish C-PODs. Pedestrian PODs (P-PODs) may include athletic

facilities or fields for distribution points. Explore potential partnerships with grocery delivery services.

Consider access to the C-POD and that public transportation nodes (e.g., metro, bus stop, and traffic

circles) can be possible distribution locations. More C-PODs are usually needed if the public transit

system is not fully operational.

3.2.5 RURAL OPERATIONS

In a rural environment, C-POD operations may require increased distance and delivery times.

Consider using data analytics to identify population locations and common commodities. Explore

opportunities to outsource distribution to third parties.

25

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

3.3 Transition Plan

The DM Plan should include considerations for transitioning from emergency shelf-stable meals to

feeding kitchens (hot rations) to demobilization. As a general rule, this transition should take place

within ten days of the response, if not sooner.

4. Inventory Management

Inventory management addresses the number of commodities and equipment that an organization

physically has on hand. Managing the acquisition, use, distribution, storage, and disposal of

commodities and equipment is vital to identifying available resources, controlling costs, and

improving the efficiency and readiness of an organization. Ineffective inventory management may

result in a shortage or surplus of resources. For an example inventory management form, see

Appendix F.

Effective inventory management starts with a plan that incorporates proper assessment of needs,

regular accounting of resources, standard, consistent, and understandable policies and procedures,

and industry best practices. Inventory management properly prioritizes matching requirements with

available resources and the order of execution.

4.1 Resource Tracking

Resource tracking is critical to inventory management. It is a standardized, integrated process

conducted throughout the life cycle of an incident to provide a clear picture of where resources are

located and help staff prepare to receive them. It should include procedures to track resources

continuously from mobilization through demobilization and display real-time information in a

centralized database, allowing total visibility of assets.

SLTTs should develop and maintain resource tracking systems as a baseline for inventory

management in a DM Plan. Resource inventories should be adaptable and scalable. While a

resource inventory can be as simple as a paper or electronic spreadsheet, many resource providers

use information technology (IT) based inventory systems. For example, some states use Excel

spreadsheets to track inventory by sorting information based on active C-PODS. Additionally, some

states utilize the reports generated from FEMA’s Logistics Supply Chain Management System

(LSCMS) to track and manage material and equipment.

The Incident Resource Inventory System (IRIS) is a distributed software tool, provided at no cost by

FEMA. It is standards-based and allows for the seamless exchange of information with other

instances of IRIS and other standards-based resource inventory and resource management systems.

IRIS allows users to identify & inventory their resources, consistently with National Incident

Management System (NIMS) resource typing definitions, for mutual aid operations based on mission

needs and each resource’s capabilities, availability, and response time. IRIS automatically uses the

national NIMS resource typing definitions cataloged in the Resource Typing Library Tool (RTLT). IRIS

stores data locally on the user’s computer or the user’s network if configured during installation.

26

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Please note IRIS is not a database centrally managed by FEMA. Users and their respective agencies

are responsible for their data.

4.1.1 FORECASTING DEMAND BASED ON CONSUMPTION RATE

Resource tracking provides information and usage data that enables a jurisdiction to forecast

demand and cross-level remaining assets, while simultaneously working with FEMA to ensure

inbound commodities reflect need.

5. Transportation

This function enables the relief supply chain, through coordinated transportation nodes and modes,

to effectively deliver goods and services in an expeditious and efficient manner. Capacity, capability,

speed, cost, resiliency, reliability, and robustness of transportation all contribute to a supply chain’s

ability to respond to demand or changes in demand while meeting mission requirements.

Jurisdictions should describe transportation architecture (e.g., key routes and nodes) and inbound

and outbound flows. Inbound flows may include commodities, equipment, and teams; outbound

flows may include retrogrades and redeployments.

Many aspects of transportation influence success or failure during a response. Assessing SLTT

capability and requirements is necessary to evaluate the organic capability and identify where

potential shortfalls exist. Capability can be difficult to identify and goes beyond an emergency

management agency’s current equipment or contracting capacity. True capability lies within the

transportation solutions and operations SLTT agencies are already engaged in, even if they are

separate from obvious emergency management connections.

Government institutions and contracts may already exist to move resources and people for routine

daily operations, such as moving commodities for population and business operations. It may be

possible to leverage that capability for emergency transportation, as a separate or additional source

for capacity. Additionally, government agency agreements and contract line-item numbers (CLINs)

could be added to provide for emergency response support, even vendors fulfilling requirements that

are seemingly unrelated to emergency response.

Assess what internal capabilities exist and what other non-emergency capacity can be leveraged

(e.g., SLTT agencies, private sector, nonprofit organization) by cataloging current transportation

capabilities. Then determine how robust and resilient the capability is, what redundancy is available

and can be developed, lead and cycle times with variance, and scalability and limits.

Once main supply chain routes are identified and their resiliency capability determined, alternative

routes should be established. These alternative routes allow for additional delivery of resources,

access to debris impacted areas, and various modes of transportation to pass through that main

supply chain routes could not provide (e.g., height for roads under bridges, debris, noise restrictions).

Regions encourage EMPG recipients to identify all forms of transportation and alternative routes, if

possible, based on previous shortfalls and best practices learned from previous executions of their

27

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

DM Plan. Geographic diversity can make this difficult but exploring robust transportation options and

developing and focusing on a whole community approach could prove to provide realistic

alternatives. EMPG recipients can also work with their local Emergency Support Function (ESF) 1:

Transportation Annex, Department of Transportation, representative, or a point of contact with their

local transportation companies to establish alternative routes and modes of transportation. Such

alternative modes of transportation can include ferries, small aircraft, and tourism-based vessels.

5.1 Modes of Transportation

Given priorities established by the operations and SLTT leadership, determine a plan for tasking,

managing, and prioritizing transportation requirements from all modes: ground, air, water, and rail.

All will have unique transit, lead, and cycle times along with a degree of reliability of those times.

Multiple methods are often combined as intermodal movements.

5.1.1 GROUND

Transporting resources by truck is an often-used capability. Tractor-trailers are the most common

method for quickly moving substantial quantities of resources in the Continental United States

(CONUS). Ground transportation also includes specialty vehicles, such as high-water, off-road, box

trucks, and lift gates. Combined with other transportation methods, ground capabilities provide

operational control and redundancy in case of failure or obstacles but may require other support

such as dispatching. Ground transportation capability may exist internally and/or require contracting

through pre-existing or spot contracts. Additionally, ground transportation must consider size of

operations and geographic access. Utilizing mixed loads in smaller quantities may make sense

based on access and population served.

5.1.2 AIR

Transportation by air can be sourced from the National Guard, the private sector, or Federal

capabilities. Determine a plan for how operations should occur, accounting for perceived capability

and actual capacity. Transport by air is often the most expensive, and while can be the quickest from

point A to B, prioritization and backlog of requested items may make other types of transportation

more feasible and timelier. Also, consider wraparound support services and agreements for

operations and services. To reach remote access point, sling loading may be necessary. Planning for

this in advance will ensure your plan has accounted for all populations and into areas with minimal

access whether normal or created by a disaster.

5.1.3 WATER

Transportation by water (e.g., barge or boat) is typical for movement outside the Continental United

States (OCONUS). Address various modes of transportation required in OCONUS areas to transport

resources and commodities for the last mile. If the jurisdiction being served has islands, it is

important to make sure the methodology for serving those populations is included in the DM Plan.

Especially in the case of a no-notice incident or if evacuation is not possible.

28

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

5.1.4 RAIL

Transportation by rail may provide a sustained supply of commodities. Establish the capacity and

capability of current private sector rail operations.

5.2 Strategic Considerations

Match distribution requirements with transportation capacity, including tracking of orders throughout

the supply chain lifecycle. This includes not only the commodity or resource, but the vehicle utilized

(e.g., trailer, container, vessel, aircraft).

Address OCONUS considerations and challenges as part of the DM Plan. Stress the importance of

and variability of lead, transit, and cycle times. Both time and variability will be more extensive than

most CONUS operations.

Other methods and sources can augment known or predictable requirements; developing a

consistent plan to execute those solutions is important. This can be achieved through a checklist

with options, an order of addressing options, and decision-making criteria.

5.2.1 MOVEMENT OF RESOURCES

Determine a plan for moving commodities and resources between staging areas, warehouses, and C-

PODs. Explore transportation as an overall lifecycle of the incident (i.e., round trip) or as segmented

requirements (i.e., each leg of the route).

Determine a list of available transportation operators who are authorized and/or cleared to transport

materials to staging areas. Availability of transportation operators may require specific

considerations for various supply chains (e.g., strict rules in healthcare supply chains on who can

transport certain products and requirements for temperature and environmental controls) and often

rely heavily on information technology and communications to direct their movements and deliveries.

Disasters on a larger scale may diminish available transport staff and alternative staff may need to

be utilized.

Determine available options (e.g., contracts, National Guard, spot contracts, EMAC), if funding

methods are in place, to acquire additional support to move resources and the cost and feasibility of

executing them. Determine possible courses of action for meeting shortfalls and an order of

execution that is scalable to cover unforeseen circumstances.

5.2.2 TRACKING MATERIAL AND EQUIPMENT

Determine the best way to track operations and measure performance, including triggers to indicate

when tactical corrections are needed. The measurement system should be repeatable, understood

by all actors, and lead to achieving mission goals.

Identify how transportation providers will enter disaster areas, especially evacuated areas, and areas

with limited and strained infrastructure. These items are often tracked:

29

Distribution Management Plan Guide 2.0

Methods of control.

Identification and validation.

Procedures.

Routes.

Entry during contraflow.

5.3 Empty Trailer Management

Planning and executing the return of equipment aids the response by reducing total units required,

reallocating resources more effectively, and preventing field operations from outgrowing their

required footprint. Tracking returned trailers needs to be a part of the SLTT jurisdiction’s

transportation management plan. A recovery system for empty trailers is simple to teach, socialize,

and integrate into existing procedures and methodology with partners. It should leverage current

common industry practices, including nomenclatures that identify the trailer number, tag number,

state, transponder number, and trailer owner.

5.4 Shuttle Fleet

Staging and distribution may utilize a shuttle fleet. At the Federal level, this consists of multiple

trucks (e.g., bobtail tractors with drivers) to transport commodities and freight to the Federal staging

area.

The typical zone of operation is an area with an “X”-mile radius. In general, a shuttle fleet can

transport commodities and equipment to any point operationally necessary for the mission within a

functional limit based on geography, contract limits, or time.. Each jurisdiction should consider its

geographic area, along with fleet capability, to establish its practical limit. This includes transporting

to state or local staging areas, C-PODs, other sites, and volunteer groups. Some jurisdictions manage

effective cross-dock operations where larger shipments and pallets are reconfigured into smaller

“box trucks” or custom loads.