Journal of Business Case Studies – July/August 2010 Volume 6, Number 4

23

Using Actual Financial Accounting

Information To Conduct Financial Ratio

Analysis: The Case Of Motorola

Henry W. Collier, University of Wollongong, Australia

Timothy Grai, Oakland University, USA

Steve Haslitt, Oakland University, USA

Carl B. McGowan, Jr., Norfolk State University, USA

ABSTRACT

In this paper, we demonstrate the use of actual financial data for financial ratio analysis. We

construct a financial and industry analysis for Motorola Corporation. The objective is to show

students exactly how to compute ratios for an actual company. This paper demonstrates the

difficulties in applying the principles of financial ratio analysis when the data are not

homogeneous, as is the case in textbook examples. We use Motorola as an example because the

firm has several segments, two of which account for the majority of sales and represent two

industries (semi-conductor and communications) that have different characteristics. The case

illustrates the complexity of financial analysis.

Keywords: Ratio Analysis, Industry Analysis, Financial Accounting Information

INTRODUCTION

Motorola Segment Analysis

otorola is a global manufacturer of communication products, semiconductors, and embedded electronic

solutions. The company is divided into six operating segments that publicly report financial results.

Financial data are provided in Appendix A. The Personal Communication Segment (PCS) designs,

manufactures, and markets wireless communication products for service subscribers. Products include wireless

handsets, personal 2-way radios, and messaging devices, along with the associated accessories. The Personal

Communication Segment accounted for 37.8% of 2002 sales, making it the largest of Motorola’s operating

segments. The Global Telecommunications Segment (GTS) designs, manufactures, and markets the infrastructure

communication systems purchased by telecommunication service providers. Products include electronic exchanges,

telephone switches, and base station controllers for various wireless communication standards. This segment

accounted for 15.8% of Motorola’s sales in 2002. The Broadband Communication Segment (BCS) designs,

manufactures, and markets a variety of products to support the cable and broadcast television and telephony

industries in delivering high speed data, including cable modems, Internet-based telephones, set-top terminals, and

digital satellite television systems. This segment accounted for 7.3% of Motorola’s sales in 2002. The Commercial,

Government, & Industrial Segment (CGIS) designs, manufactures, and markets integrated communication systems

for commercial, government, and industrial applications, typically private 2-way wireless networks for voice and

data transmissions, such as would be used by public safety authorities in a community. This segment accounted for

13% of Motorola’s sales in 2002. The Semiconductor Product Segment (SPS) designs, manufactures, and markets

microprocessors and related semiconductors for use in various end products, such as computers, wireless and

broadband devices, automobiles, and other consumer electronic devices. Some of the semiconductors produced are

used in products marketed by other Motorola segments. This segment accounted for 16.8% of Motorola’s sales in

2002. The Integrated Electronic Systems Segment (IESS) designs, manufactures, and markets automotive and

industrial electronic systems, single board computer systems, and energy storage products to support portable

electronic devices (such as wireless handsets). This segment accounted for 7.6% of Motorola’s sales in 2002.

M

Journal of Business Case Studies – July/August 2010 Volume 6, Number 4

24

Total Motorola sales and profitability have varied widely over the last five years, as shown in Table 1.

Sales peaked at over $37B in 2000 and dropped to less than $27B in 2002. Motorola had a net loss in 2001 and

2002. Motorola’s stock price has varied from a high of over $55 in February of 2000 to a low price of less than $8

in January of 2003. Despite the losses incurred recently and the variability of reported income, Motorola has

continued to pay a steady dividend of $0.16 per share since 1997. This is a clear indication of the importance that

Motorola attaches to the informational content associated with dividends; despite significant losses, dividends have

not been reduced. The most recent data indicates that Motorola has returned to profitability, posting a $0.01 per

share profit for the first quarter of 2003.

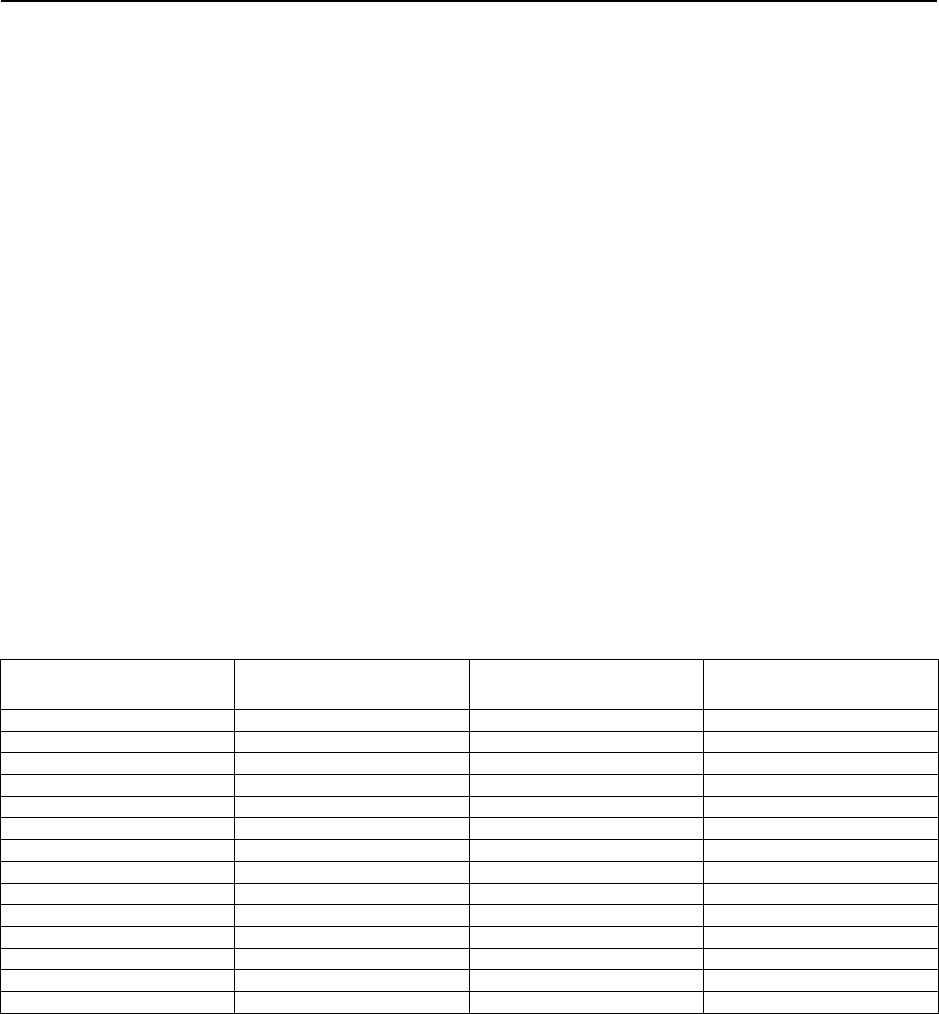

Table 1: Condensed Statement of Financial Performance 1998 to 2002

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

Sales

26,679

30,004

37,580

33,075

31,340

Net Earnings

(2,485)

(3,937)

1,318

891

(907)

Note: All figures in millions except per share data, as is typical in this report, unless noted.

Industry Analysis

The Telecommunications Equipment Industry

The telecommunications equipment industry provides the products required to support land-based and

wireless communications, both the end-consumer equipment and the infrastructure of the networks that enable the

end-consumer products. Data for companies in the telecommunications industry are shown in Appendix B. Nokia

is the market leader in the handset portion of this industry, followed by Motorola, Siemens and Sony-Ericsson.

Ericsson leads the infrastructure portion of the equipment industry. The five largest companies are Cisco Systems,

Nokia, Qualcomm, Motorola, and Ericsson (yahoo.marketguide.com).

The telecommunications equipment industry, in particular, has seen difficult operating conditions among

the technology industries over the last several years. The difficult operating conditions are the result of two

underlying issues. First, after a rapid build-up of wireless network infrastructure by the service providers (firms

such as Verizon Wireless that provide telecommunication services to the end-consumer) in 2000, the demand for

equipment by the service providers dropped some 15% in 2001 and likely dropped by even a higher percentage in

2002 (Yahoo.finance). Second, the demand for third generation (3G) wireless technologies (which includes mobile

data services that can combine voice, data, email, PDA, and other features) has not evolved as quickly as expected.

Wireless subscribers have chosen not to replace their handsets with the new 3G technologies in anticipation of the

price of the equipment dropping (Yahoo.finance).

The telecommunication equipment industry has a beta coefficient of 2.09, explaining, in part, the difficult

operating conditions in the industry as a magnification of the poor conditions in the economy as a whole

(yahoo.marketguide.com). A key segment within the telecommunications industry is the wireless handset (cellular

phone) segment, both because of its size and because of its visibility to end-consumers. In this wireless handset

segment, Nokia is the clear market leader, with a substantial 35.8% market share in 2002 and a strong presence in

the critical European market. This is important because Europe is where much of the technological innovation in the

industry occurs. Motorola is in second place in this industry segment with a market share of 15.3%, less than half of

Nokia’s share. Third place belongs to Samsung, with a 9.8% market share, but Samsung’s strong technology and

significant resources pose significant challenges to Motorola and Nokia’s leadership positions. Siemens held an

8.4% market share in 2002, while the joint venture between Sony and Ericsson held a 5.5% market share in the

industry segment (Reiter, 2003).

The Semiconductor Industry

The semiconductor industry provides the semiconductor “chips”, which are integral to consumer

electronics, such as PC’s, PDA’s, audio, visual and entertainment equipment, and cellular phones. Data for

Journal of Business Case Studies – July/August 2010 Volume 6, Number 4

25

companies in the semiconductor industry are shown in Appendix C. These chips are also used in commercial

electronics, such as network servers, communication switch equipment, and industrial controls. Intel is the largest

firm in the industry. Intel is known, in particular, for supplying the microprocessors used in PC’s. The top five

companies in this industry, in order of descending market capitalization, are Intel, Texas Instrument, Taiwan

Semiconductor, Advanced Materials, and ST-Microelectronics (yahoo.marketguide.com).

The semiconductor industry experienced a record year in 2000 with worldwide sales of $200B. Sales

experienced a significant declined in 2001, down some 30% to $140B. The decline in 2001 was attributed to weak

sales in nearly every consumer electronics segment and to weak sales in commercial electronic segments, resulting

in low demand for semiconductors (yahoo.finance). The year 2002 brought only a slight recovery in the

semiconductor industry, with an expected worldwide sales increase likely to be only several percentage points

higher than 2001 levels. November 2002 sales only increased by 1.3%, less than the 1.8% increase in October 2002.

This low increase is significant because November sales have historically averaged larger increases as electronic

manufacturers prepare for the holiday season (Value Line, January 17, 2003, p 1051). The semiconductor industry

has a Beta coefficient of 2.17, which, like the telecommunication equipment industry, explains, in part, the severe

downturn in the industry as the entire economy took a downturn over the last several years

(yahoo.marketguide.com).

Financial Ratio Analysis

Financial ratios for Motorola, for the semiconductor industry, and for the telecommunications industry are

provided in Table 2. The firms in the semiconductor industry subset represent 87% of the estimated total

semiconductor industry sales of $100 billion in 2002 (Value Line, January 3, 2003, pp. 744 and pp. 770). The firm’s

telecommunications equipment industry represented 91% of telecommunication equipment industry sales of $277

billion in 2002 (Value Line, January 17, 2003, p 1051).

Table 2: 2002 Ratio Analysis

Motorola

Semiconductor

Industry

Telecommunication

Equipment Industry

Current Ratio

1.77

2.44

1.52

Quick Ratio

1.47

2.08

1.23

Average Collection Period

61 days

50 days

73 days

Inventory Turnover

6.25

6.01

5.66

Fixed Asset Turnover

4.37

1.58

6.24

Total Asset Turnover

0.86

0.61

0.90

Debt Ratio

0.64

0.34

0.65

Debt to Equity Ratio

1.77

0.52

1.82

Times Interest Earned

NA

NA

NA

Gross Profit Margin

32.76%

37.49%

29.52%

Net Profit Margin

-9.31%

-3.00%

-1.24%

Return on Investment

-7.98%

-1.82%

-1.11%

Return on Equity

-22.11%

-2.78%

-3.14%

Assets / Equity

2.77

1.52

2.82

Note: Ratios are derived from the data in Appendices A, B, and C.

Evaluating Motorola relative to the semiconductor industry, we first note that Motorola is slightly less

liquid than the average firm in the industry, with both a current ratio and a quick ratio that is lower than the industry

average. Motorola’s average collection period, at 61 days, is lower than the industry average of 50 days, indicating

Motorola should evaluate its credit policies. Both fixed asset turnover and total asset turnover are above the

semiconductor industry averages, indicating that Motorola is using its assets more efficiently than the industry

average in generating sales. Motorola’s debt ratio and debt-to-equity ratio indicate that Motorola is more leveraged

than the average firm in the industry. This higher leverage, in part, explains Motorola’s poor financial performance

relative to the semiconductor industry because the leverage commits Motorola to interest payments that must be paid

Journal of Business Case Studies – July/August 2010 Volume 6, Number 4

26

regardless of economic and market conditions. The ratios indicate that Motorola has a higher cost of sales than the

average firm in the semiconductor industry, resulting in a lower gross profit margin and higher indirect costs,

resulting in lower net profit margin performance relative to the semiconductor industry.

The situation is different when evaluating Motorola relative to the telecommunications equipment industry

and, considering that the majority of Motorola’s business is in this industry rather than the semiconductor industry,

this is the more interesting and relevant story. Relative to the telecommunications equipment industry, Motorola has

a better liquidity position, with both the current ratio and the quick ratio being higher than the industry average.

Motorola collects receivables quicker than the average firm in this industry. Relative to this industry, Motorola may

want to evaluate credit policies to determine if perhaps strict credit policies are negatively impacting sales.

Motorola uses its total assets slightly less efficiently than the average firm in the telecommunications equipment

industry and its fixed asset turnover is significantly less than the industry average, at 4.37 compared to the industry

average of 6.24. Motorola is more highly leveraged than the average firm in the telecommunications industry.

Motorola may want to examine its capital structure policy to ensure it has the right balance of benefit from the tax

shield of increased debt relative to the bankruptcy and related financial distress costs associated with increased debt.

Several explanations are possible for the deviation from industry norms. Perhaps this is the result of a

conscious choice to invest heavily in technology and automation in its manufacturing processes (as opposed to a

more labor-intensive manufacturing strategy). While such fixed investments will yield significant gains in good

market conditions, the investments commit the firm to fixed costs (depreciation), even in bad economic conditions.

Alternatively, the poor fixed asset turnover may indicate overcapacity caused by extremely poor forecasts of future

sales. Or, the poor ratio may indicate a fundamental inability or inefficiency in using the deployed assets. Motorola

is slightly less leveraged, with a lower debt and debt-to-equity ratio. Keep in mind, though, that the debt ratios used

in the ratio analysis above used total liabilities as a measure of debt. In contrast, capital structure analysis focuses

specifically on long-term debt in calculating leverage.

Motorola has a higher gross profit margin than the average firm in the telecommunications equipment

industry (32.8% versus 29.5%), but has a lower net margin. Motorola has a higher fixed and indirect cost structure.

As an illustration of the potential fixed and indirect cost issues, consider the productivity, which for this purpose is

defined as sales per employee, of Motorola relative to its chief competitor in the telecommunications equipment

industry - Nokia. In 2001, Motorola generated sales of $31,191M with 111,000 employees for a productivity of

$0.27M per employee. In contrast, Nokia generated sales of $27,645M with just 53,800 employees, for a

productivity of $0.53M per employee - nearly double the productivity of Motorola. Clearly, Motorola has

significant costs associated with its level of employment that are not being returned in sales. This is interesting

because Motorola, as observed earlier, also has poor fixed asset use in addition to this effective and/or efficient use

of human assets. Perhaps contributing to the poor fixed and indirect cost structure is that Motorola has elements of

being a conglomerate that most of the other firms in the industry do not have. Motorola is involved in diverse

business segments – telecommunications, semiconductors, automotive components, and batteries, to name a few –

and must evaluate whether the administrative and infrastructure costs of managing these diverse segments are less

than the benefits of having the segments under one corporate umbrella. It is not obvious that the diverse business

segments within Motorola are being used synergistically to increase overall value. If there are not synergies between

the business segments, Motorola shareholders should prefer that Motorola divest the segments as investors can

diversify their portfolios more efficiently than Motorola can. Most of the other firms in the industry do not have to

absorb the costs associated with managing such diverse business activities.

DuPont System of Financial Analysis

A DuPont analysis of Motorola, the semiconductor industry, and the telecommunications equipment

industry is shown in Table 3. The story told by the DuPont analysis is similar to the story told by analyzing ratios;

i.e., Motorola must focus on controlling operating costs. Relative to the semiconductor industry as a whole,

Motorola has an advantage in its leverage ratio (Assets to Equity of 2.77 compared to 1.52 for the industry) and in

its use of assets (Total Asset Turnover of 0.86 compared to 0.61), yet has a poorer return on equity due to its low net

profit margin. While one would expect a somewhat lower net profit margin for a firm with a higher leverage ratio

(the firm has to pay interest to service the debt that gives the higher leverage ratio), in the Motorola case there are

Journal of Business Case Studies – July/August 2010 Volume 6, Number 4

27

apparently other operational inefficiencies impacting the net profit margin because the overall return on equity is

less than the industry average. A similar story, though not quite as obvious, is told by comparing Motorola to the

telecommunications equipment industry averages for the DuPont analysis, where Motorola again stands out as being

deficient in its ability to generate profits from its sales.

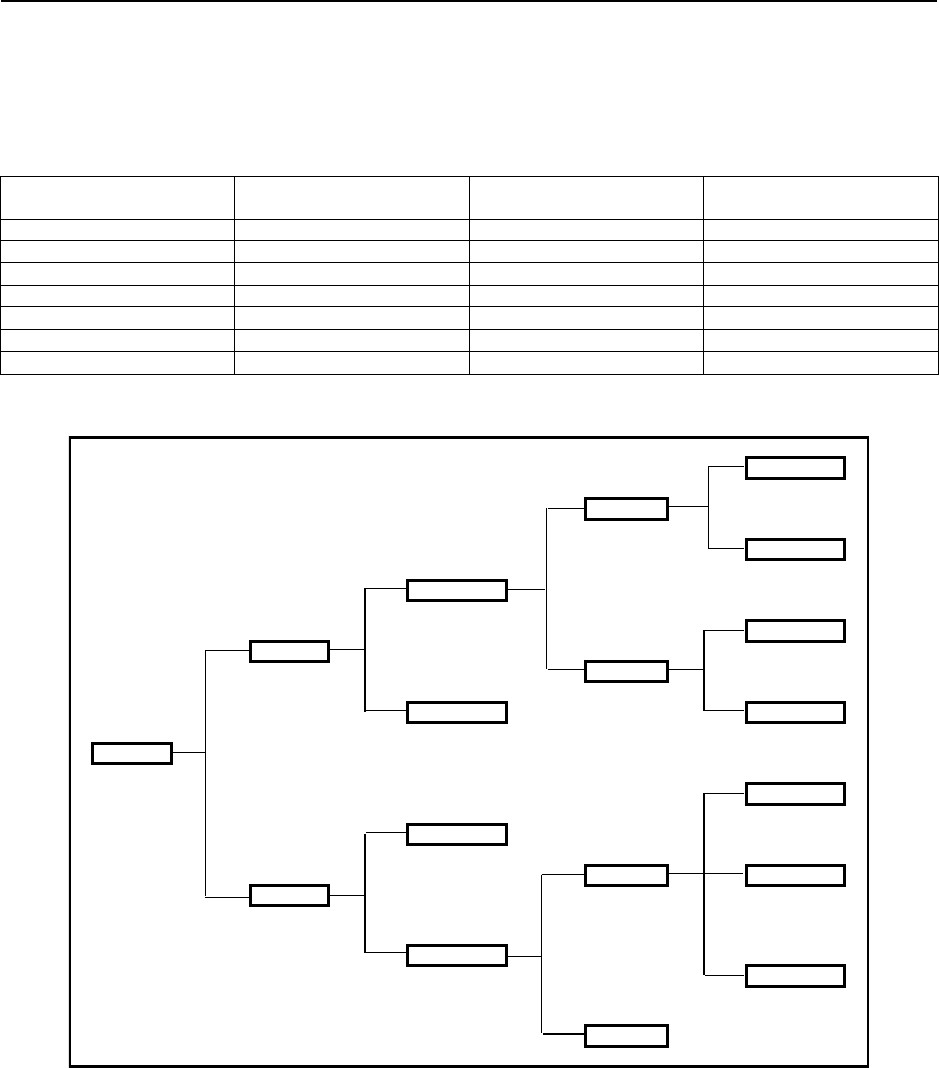

Table 3: The DuPont Analysis of Motorola and Industries

Motorola

Semiconductor Industry

Telecommunication

Equipment Industry

ROE (Return on Equity)

-22.11%

-2.78%

-3.14%

=

=

=

=

NPM (Net Profit Margin)

-9.31%

-3.00%

-1.24%

X

X

X

X

TAT (Total Asset Turnover)

0.86

0.61

0.90

X

X

X

X

A/E (Assets/Equity)

2.77

1.52

2.82

Figure 1: ROA Analysis for Motorola - 2002

Sales

Gross 26,679

Margin

8,741 -

COGS

17,938

Net Profit

(2,485) - Variable

Expenses

NPM 7,957

-9.3% / Expenses +

11,226 Fixed

Sales Expenses

26,679 3,269

ROA

-8.0% X

Inventory

2,869

Sales +

26,679 Current Accounts

Assets Receivable

TAT 17,134 4,437

0.86 / +

Other

Total Assets Current

31,152 + Assets

9,828

Fixed

Assets

14,018

ROA Analysis

Figure 1 shows the Return on Asset (ROA) portion of the DuPont analysis

ROE = NPM * TAT * A/E = ROA * A/E (1)

and helps to illustrate Motorola’s situation. Large variable and fixed expenses (relative to the level of sales) are

negatively impacting ROA, and these expenses, especially variable expenses (selling, general, and administrative

expenses) since they are perceived to be more easily controllable, need to be closely evaluated. Increases in sales

Journal of Business Case Studies – July/August 2010 Volume 6, Number 4

28

revenues may also help the ROA situation. Although poor overall market conditions can be blamed for a portion of

Motorola’s low sales figure, Motorola also needs to critically evaluate why it has lost market share in some of its

key business areas over the last several years (for example, Nokia’s and Samsungs market share in wireless handsets

has improved while Motorola’s has declined) making the operating results from poor market conditions even worse.

The impact of Motorola’s decision early in the lifecycle of the cellular industry not to participate in developing

digital cellular technology likely opened the door for firms such as Nokia to gain significant market positions, and

Motorola’s sales – and its financial position - still suffer from this decision. New product development investments

must be closely evaluated to assure that Motorola is developing products that will be valued in the marketplace.

However, competitors will not simply let Motorola gain sales and market share at their expense. Nokia capitalized

on Motorola’s incorrect earlier strategic decision to forego entry in the digital wireless handset arena. Nokia gained

a dominant position in Europe and is now clearly aiming to challenge Motorola’s leadership in CDMA wireless

handset technology in the United States through the introduction of multiple new handset models based on the

CDMA technology prevalent in America (Nokia Unveils New Phones to Crack CDMA). Motorola and Nokia are

also losing share in foreign markets, such as China, because domestic firms in those markets use price advantages to

drive sales (Nokia, Motorola Lose China Market Share to Domestic Companies). Motorola must develop a product

and business strategy to increase sales in the midst of these threats, while at the same time controlling variable and

fixed expenses.

Short Term Liquidity Management

As shown in Table 4, the telecommunication equipment industry averages a current ratio of 1.52 and a

quick ratio of 1.23, so Motorola’s current ratio and quick ratio of 1.77 and 1.47, respectively, compares favorably to

the industry. This, combined with the observation that both ratios are above one, leads to the conclusion that

Motorola is in a solid short-term liquidity position. While this favorable absolute liquidity position is important,

perhaps just as important to debt investors in Motorola is the trend over time in the ratios. In Motorola’s case, there

have been very solid improvements in its liquidity position since 1999 and 2000. Some of this improvement in

liquidity comes from reductions in notes payable and the current portion of long-term debt. But a significant portion

of the improvement is attributable to large increases in cash and cash equivalents. The cash and cash equivalent

balance increased 97% percent during period. In addition to the cash increases seen above. Motorola has very

recently taken additional steps to “further boost” its cash position by selling $325M of Nextel stock (Motorola Sells

$325M of Nextel Stock). This sale of 25 million of Motorola’s 108 million Nextel shares was completed “to realize

the price appreciation of some of its investment in the wireless communications services provider and to enhance its

already strong cash position” (Motorola Completes Sale of 25 Million of Its 108 Million Shares of Nextel). After

the sale, Motorola will remain one of Nextel’s largest shareholders, retaining over a 9% stake in Nextel (Motorola

Sells $325M of Nextel Stock).

Table 4: Short-term Liquidity Analysis

2002

2001

2000

1999

Cash and cash equivalents

6,507

6,082

3,301

3,537

Short-term investments

59

80

354

699

Accounts receivable, net

4,437

4,583

7,092

5,627

Inventories, net

2,869

2,756

5,242

3,707

Other current assets

3,262

3,648

3,896

4,015

Total current assets

17,134

17,149

19,885

17,585

Notes payable & current portion of long-term debt

1,524

870

6,391

2,504

Accounts payable

2,268

2,434

3,492

3,285

Accrued liabilities

5,913

6,394

6,374

7,117

Total current liabilities

9,705

9,698

16,257

12,906

Current Ratio

1.77

1.77

1.22

1.36

Quick Ratio

1.47

1.48

0.90

1.08

Net Working Capital

7,429

7,451

3,628

4,679

Journal of Business Case Studies – July/August 2010 Volume 6, Number 4

29

Capital Structure & Debt Management

From Table 5, it is evident that there has been a significant change in Motorola’s capital structure over the

last several years. When viewed from either a book value or market value basis, there is a significant increase in

leverage. Motorola’s long-term debt increased by more than 85% from 2000 to 2001, while equity dropped on both

a book value and market value basis. From the data, it does not appear that Motorola has a strict or a tight target

debt-equity ratio that they maintain to balance the benefits of debt (primarily, the tax savings due to interest) with

the cost of debt (primarily, financial distress costs), unlike many large firms (Graham and Harvey, 2001). It is

unclear whether Motorola has a strategy to minimize their weighted average cost of capital.

Table 5: Financial Leverage Analysis for Motorola

2002

2001

2000

1999

Long Term Debt, Book Value ($M)

7,779

8,857

4,778

3,573

Long Term Debt, Market Value ($M)

7,722

8,857

4,778

3,573

Stockholders Equity, Book Value ($M)

11,239

13,691

18,612

18,693

# Shares (M)

2,301

2,213

2,257

2,202

Share Price ($)

8.01

16.05

19.59

44.72

Stockholders Equity, Market Value ($M)

18,431

35,523

44,207

98,473

Debt/Equity (Book Value)

0.69

0.65

0.26

0.19

Debt/Equity (Market Value)

0.42

0.25

0.11

0.04

Note: 2001, 2000, 1999 market value of debt is assumed to be the same as book value of debt.

Some of the increase in long-term debt from 2000 to 2001 was used to replace short-term debt (Motorola

2001 Proxy Statement). However, we observed earlier that cash balances increased significantly in the same time

period, indicating that some of the long-term financing was used to improve the short-term liquidity position. But

these improvements in the short-term liquidity position came at the expense of an increase in operating risk. The

increased leverage committed the company to increase interest payments to service the long-term debt. Interest

payments increased from $529M to $844M from 2000 to 2001, increasing Motorola’s losses in 2001 as economic

and market conditions worsened (Motorola 2001 Proxy Statement). The significant amount of debt added in 2001

could also impact Motorola’s ability to acquire long-term debt at favorable rates in the future. If funds are needed

beyond what are available internally, Motorola may have no choice but to turn to the equity market, which is

generally considered to be unfavorable at this point in time. The increase in long-term debt may, in part, support the

free cash flow hypothesis, which asserts that bad investment decisions are often made in the presence of a large

amount of free cash flow.

While we have examined Motorola’s capital structure from an absolute perspective, it is worthwhile to look

at the capital structure relative to the industry segment that Motorola primarily participates in - the

telecommunications equipment industry. Company-wide financial structure data are shown in Table 6.

Table 6: Financial Leverage Analysis for Industry

Industry

Long Term Debt, Book Value ($M)

56,347

Stockholders Equity, Book Value ($M)

119,349

Stockholders Equity, Market Value ($M)

270,389

Debt/Equity (Book Value)

0.47

Debt/Equity (Market Value)

0.21

In Table 5, Motorola’s debt-equity ratio, on a book value basis, is 0.69, which is higher than the industry

average of 0.42, from in Table 6 and Motorola’s debt-equity ratio on a market value basis is 0.47, double the

industry average of 0.21. So, Motorola has not only increased its leverage, it has increased its leverage well above

the industry average leverage ratio. Is this bad in the sense that the higher leverage level is detracting from firm

value? We believe that this question is difficult to answer with information from publicly available sources. The

Journal of Business Case Studies – July/August 2010 Volume 6, Number 4

30

appropriate amount of leverage is unique to each firm based on the firm balancing the tax benefits of increased debt

against the financial distress costs associated with increased debt. However, the deviation from the industry average

leverage ratio should be closely examined as, on average, other firms in similar business situations see the

appropriate balance between the tax shelter benefit and distress costs at much lower levels of leverage.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we demonstrate that financial ratio analysis using data for an actual company – Motorola -

and industry - telecommunications and semiconductor - is complicated and is further complicated for companies that

do not readily fall into a single industry. Motorola has six operating units that fall into several industries with two

industries accounting for most of the sales – telecommunications and semi-conductor. The differences in the

industry characteristics of these two industries complicate the financial ratio analysis of Motorola. However, a more

relevant picture of the operating characteristics of Motorola is achieved by increasing the complexity of the analysis;

that is, by comparing Motorola to both industries.

AUTHOR INFORMATION

Henry W. Collier is a faculty member emeritus of accounting at the University of Wollongong. Professor Collier

has published in numerous journals including The Accounting Educators' Journal, Applied Financial Economics,

Asia Pacific Journal of Finance and Banking Research, The Journal of Current Research in Global Business, The

Journal of Diversity Management, Financial Practice and Education, Managerial Finance,

Timothy Grai works in the automobile industry and is a former MBA student at Oakland University.

Steve Haslitt works in the automobile industry and is a former MBA student at Oakland University.

Carl B. McGowan, Jr., PhD, CFA is a Professor of Finance at Norfolk State University. Dr. McGowan has a BA

in International Relations (Syracuse), an MBA in Finance (Eastern Michigan), and a PhD in Business

Administration (Finance) from Michigan State. From 2003 to 2004, he held the RHB Bank Distinguished Chair in

Finance at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia and has taught in Cost Rica, Malaysia, Moscow, Saudi Arabia, and

The UAE. Professor McGowan has published in numerous journals including Applied Financial Economics,

Decision Science, Financial Practice and Education, The Financial Review, International Business and Economics

Research Journal, The Journal of Applied Business Research, The Journal of Diversity Management, The Journal of

Real Estate Research, Managerial Finance, Managing Global Transitions, The Southwestern Economic Review, and

Urban Studies.

REFERENCES

1. Brigham, Eugene F. and Joel F. Houston. Fundamentals of Financial Management, Ninth Edition,

Harcourt College Publishers, Fort Worth, 2001.

2. Graham, John R. and Campbell R. Harvey. “The Theory and Practice of Corporate Finance: Evidence

from the Field,” Journal of Financial Economics, 60, 2001, pp. 187-243.

3. Motorola Completes Sale of 25 Million of Its 108 Million Shares of Nextel, retrieved from

http://biz.yahoo.com/prnews/030304/cgtu025_1.html

4. Motorola Sells $325M of Nextel Stock, retrieve from

http//biz.yahoo.com/ap/030305/Motorola_Nextel_1.html

5. Nokia Unveils New Phones to Crack CDMA Market, retrieved from

http://biz.yahoo.com/rc/030317_tech_nokia_handsets_2.html

6. Nokia, Motorola Lose China Market Share to Domestic Companies, retrieved from

http://biz.yahoo.com/djus/030314/0020000011_1.html

7. Reiter, Chris. Mobile Phone Sales Rose 6% to 423 Million Units Last Year, Dow Jones Business New,

retrieved from http://biz.yahoo.com/djus/030309/2037000327_3.html

8. Yahoo.finance.com

9. Yahoo.marketguide.com

Journal of Business Case Studies – July/August 2010 Volume 6, Number 4

31

APPENDIX A

Motorola

Segment Sales and Earnings

2002

2001

Segment

Sales

%Sales

OE

OM

Sales

%Sales

OE

%OE

d(Sales)

PCS

10847

37.8%

804

7.4%

10436

33.2%

-318

-3.0%

3.9%

SPS

4818

16.8%

-283

-5.9%

4936

15.7%

-1000

-20.3%

-2.4%

GTSS

4540

15.8%

-11

-0.2%

6442

20.5%

32

0.5%

-29.5%

CGISS

3729

13.0%

361

9.7%

3850

12.3%

350

9.1%

-3.1%

BCS

2087

7.3%

257

12.3%

2854

9.1%

450

15.8%

-26.9%

IESS

2189

7.6%

115

5.3%

2239

7.1%

-12

-0.5%

-2.2%

OPS

486

1.7%

-267

-54.9%

658

2.1%

-212

-32.2%

-26.1%

Total

28696

100.0%

976

31415

100.0%

-710

-8.7%

OE

Operating Earnings

OM

Operating Margin

PCS

Personal Communications Segment

SPS

Semiconductor Products Segment

GTSS

Global Telecom Solutions Segment

CGISS

Commercial, Government, and Industrial Solutions Segment

BCS

Broadband Communications Segment

IESS

Integrated Electronic Systems Segment

OPS

Other Products Segment

APPENDIX B

Motorola

Telecommunications Industry

Alcatel

Cisco

Ericcson-

Lucent

NEC

Nortel

Nokia

Qualcomm

Siemens

Motorloa

Tele

Sony

Networks

Comm

ALA

CSCO

EDICY

Lucent

NIPNY

NT

NOK

QCOM

MOT

Industry

Assets

Accts Receivable

14956

1105

2923

1647

7737

2923

6143

925

16358

4437

59154

Inventory

4681

880

6741

1363

5366

1579

1920

88

11462

2869

36950

Current Assets

24650

17433

22926

7629

19854

11762

16664

4384

47325

17134

189760

Net Fixed Assets

4202

4102

1887

3503

9206

2571

2700

686

12612

6104

47573

Total Assets

36549

37795

29345

17791

41365

21137

24088

6510

83711

31152

329443

Liabilities

Current Liabilities

15547

8375

10754

6326

16148

9611

10275

675

37283

9705

124698

Long Term Debt

5879

0

6118

4986

15013

4094

304

94

11002

8857

56347

Total Liabilities

26700

9124

20882

20845

29451

15676

11015

1073

57867

19913

212546

Shareholder Equity

9849

28671

8464

-3054

11914

5461

13074

5437

25844

11239

116897

L&SE

36549

37795

29345

17791

41365

21137

24088

6510

83711

31152

329443

Revenues

25353

18915

27208

12321

42109

17511

33501

3040

90238

26679

296874

COGS

19074

6902

20408

10769

32287

14167

21252

1137

65314

17938

209248

Gross Profit

6279

12013

6799

1552

9822

3344

12249

1902

24925

8741

87626

Interest

679

382

2060

311

167

26

101

356

4081

Taxes

-1261

-1034

4757

-1231

-3252

1280

101

912

-961

-689

Net Income

-4963

-2495

11753

-2576

-8414

2363

360

2789

-2485

-3668

Price

7

13

6

2

3

2

13

34

39

8

Shares Outstanding (M)

1260

7110

1660

3910

1650

3850

4790

789

888

2301

Market Capitalization

8253

92501

6100

6100

5726

7970

60689

27012

34329

18431

270389

Journal of Business Case Studies – July/August 2010 Volume 6, Number 4

32

APPENDIX C

Motorola

Semi-Conductor Industry Data

Advance

Analog

Atmel

Fairchild

Intel

Maxim

Micron

National

NVIDIA

ST

Staiwan

Texas Inst

XILINK

Motorola MOT

Semi

Micro

Devices

Semi

Micro

Semi

Instrument

Conductor

AMD

ADI

ATML

FCS

INTC

MXIM

MU

NVDA

STM

TSM

TXN

XLNX

MOT

Industry

Assets

Accts Receivable

660

218

187

134

2607

130

538

132

147

902

571

1198

148

4437

12008

Inventory

381

247

302

209

2253

139

545

145

214

743

281

751

79

2869

9157

Current Assets

2353

3435

1189

875

17633

1236

2119

1073

1234

4558

2024

5775

999

17134

61636

Net Fixed Assets

2739

908

1652

660

18121

746

4700

737

120

5888

7183

5589

450

6104

55596

Total Assets

5647

4885

3024

2149

44395

2011

7555

2289

1503

10798

11262

15779

2335

31152

144784

Liabilities

Current Liabilities

1314

528

735

199

6570

229

753

404

434

1687

953

1580

196

9705

25286

Total Liabilities

2092

2042

1538

1341

8565

270

1189

508

739

4687

2617

3900

432

19913

49831

Shareholder

Equity

3555

2843

1487

808

35830

1741

6367

1781

764

6111

8645

11879

1904

11239

94953

L&SE

5647

4885

3024

2149

44395

2011

7555

2289

1503

10798

11262

15779

2335

31152

144784

Revenues

3892

2277

1472

1408

26539

1025

2589

1495

1370

6357

3675

8201

1016

26679

87993

COGS

2590

1008

1058

1054

13487

312

2700

941

850

4047

2636

5824

558

17938

55003

Gross Profit

1302

1269

415

354

13052

713

-111

553

519

2310

1039

2377

458

8741

32991

Interest

61

63

57

104

17

16

13

90

61

0

356

838

Taxes

-15

151

-113

-22

892

128

-92

-2

76

61

-107

-225

-79

-961

-308

Net Income

-61

356

-418

-42

1291

259

-907

-122

177

257

-628

-201

-114

-2485

-2637

Price

4.94

23.4

2.01

10.55

15.43

30.75

8.16

13

10.03

17.65

15.46

18.76

8.01