Ignition Interlocks –

What You Need

To Know

A Toolkit for Policymakers,

Highway Safety Professionals,

And Advocates

Second Edition

February 2014

(updated November 2019)

This publication is distributed by the U.S. Department of

Transportation, National Highway Trafc Safety Administration,

in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, ndings, and

conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors

and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation

or the National Highway Trafc Safety Administration. The

United States Government assumes no liability for its content

or use thereof. If trade or manufacturers’ names or products

are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to

the object of the publication and should not be construed as an

endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse

products or manufacturers.

Mayer, R. (2019, November). Ignition interlocks – A toolkit for program administrators,

policymakers, and stakeholders. 2nd Edition. (Report No. DOT HS 811 883). Washington,

DC: National Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

i

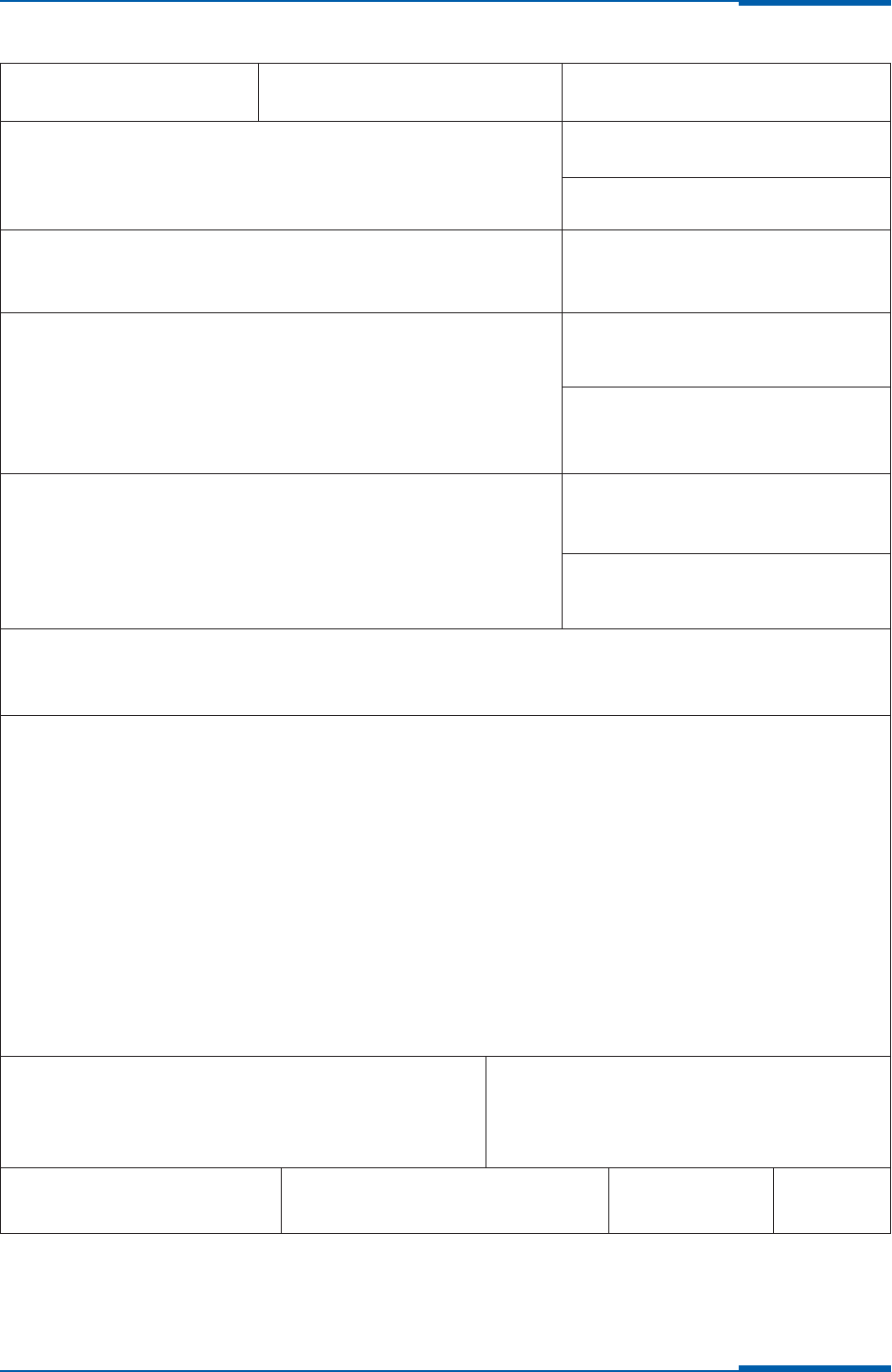

Technical Report Documentation Page

1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No.

DOT HS 811 883

4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date

Ignition Interlocks – What You Need to Know: A Toolkit for

Policymakers, Highway Safety Professionals, and Advocates

(2nd Edition)

November 2019

6. Performing Organization Code

7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No.

Robin Mayer

9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS)

Mayer & Associates

53 Church Street

Damariscotta, ME 04543

11. Contract or Grant No.

DTRTAC-11-P-00040,

Task 3.2.b

12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered

Department of Transportation

National Highway Trafc Safety Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue SE.

Washington, DC 20590

Report

14. Sponsoring Agency Code

15. Supplementary Notes

Maureen Perkins, Task Order Manager

16. Abstract

This toolkit is designed to provide basic information regarding ignition interlocks and considerations for

program administrators and policy makers in designing an efcient program.

The general topics in the toolkit include

• Description of an interlock device and how it works,

• Brief summary of interlock technology development,

• Ignition interlock research,

• Program implementation,

• Vendor selection and management, and

• Program costs.

In addition, the status of each State’s interlock program is provided, as are a series of frequently asked questions,

sample talking points and administrative forms, and checklists to aid in program planning and implementation.

17. Key Words 18. Distribution Statement

Alcohol; Ignition Interlock; Driving While Intoxicated;

DWI

Document is available to the public from

the National Technical Information Service

www.ntis.gov.

19 Security Classif. (of this report) 20. Security Classif. (of this page) 21 No. of Pages 22. Price

Unclassied Unclassied 60

Form DOT F 1700.7 (8/72)

Reproduction of completed page authorized

iii

Table of Contents

Introduction..................................................................1

How to Use the Toolkit .........................................................2

What Is an Ignition Interlock? ...................................................3

Summary of Interlock Development ...........................................3

Ignition Interlock Research .....................................................5

Effects on DWI Recidivism ..................................................5

Compliance Rates and Circumvention.........................................5

Removal of an Interlock at Completion of the Sanction ...........................6

Support for Interlocks ......................................................6

Interlocks and Substance Abuse Treatment .....................................6

Interlock Program Implementation ...............................................7

Benets of an Ignition Interlock Program.......................................7

Types of Interlock Programs .................................................8

Interlock Programs: Getting Started...........................................8

Program Goals ........................................................9

Stakeholder Involvement ...............................................10

Program Planning ....................................................10

Vendor Selection and Oversight .............................................12

Offender Monitoring and Reporting .........................................13

Interlock Program Costs .......................................................15

Indigent Funds ...........................................................15

References ..................................................................17

Resources...................................................................20

Appendices

A: Frequently Asked Questions.............................................21

B: State Ignition Interlock Laws, Regulations, and Program Information...........24

C: Publicity and Promotion................................................33

D: Internal Planning and Preparation .......................................36

E: External Relationships With Vendors .....................................39

F: Sample Forms ........................................................45

1

Introduction

Signicant strides have been made in reducing alcohol-impaired driving since the mid 1990s,

yet this offense continues to kill more than 10,000 people in the United States each year.

1

Therefore, the prevention of impaired driving continues to be critical to reducing alcohol-

impaired-driving deaths and injuries.

To combat this continuing trafc safety problem, all States have enacted legislation requiring or

permitting the use of breath alcohol ignition interlock devices (hereinafter referred to as “igni-

tion interlocks” or “interlocks”) to prevent alcohol-impaired driving.

An ignition interlock is an after-market device installed in a motor vehicle to prevent a driver

from operating the vehicle if the driver has been drinking. Before starting the vehicle, a driver

must breathe into the device and if the driver’s blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is above a

pre-set limit or set point,

2

the ignition interlock will not allow the vehicle to start.

Ignition interlocks have been used to prevent impaired driving in the United States for more

than 20 years. Over the years they have become more accurate, reliable, available, and less

costly to install and maintain, making them a valuable tool to separate a driver who has been

drinking from operating his/her motor vehicle, thereby decreasing the incidences of driving

while impaired and increasing public safety.

A number of research studies have been conducted examining the effectiveness of interlocks

and case studies have been published highlighting the operation of State ignition interlock pro-

grams. In addition, a variety of reports have been published providing guidance to establish,

expand, and strengthen State programs.

This toolkit brings together resources that explain and support the use of alcohol ignition inter-

locks, identies issues faced by ignition interlock programs and includes information on the cur-

rent use of interlocks in each State and the District of Columbia. It is designed to advance the

understanding of ignition interlock technology, improving its application as an effective strategy

to save lives and prevent impaired driving injuries.

1

NHTSA, 2012.

2

State law establishes the set point, which, in most States, is .02 grams per deciliter.

2

How to Use the Toolkit

This toolkit is designed as a quick resource, identifying and describing elements that should be

considered when establishing or strengthening a State ignition interlock program. As such, it

is not designed to necessarily be read from start to nish. Rather, the reader is encouraged to

select sections of immediate interest or need. Because of this, however, the reader will nd some

redundancy between sections.

Examples and checklists to aid in the understanding and usefulness of the information are

included where appropriate. In some instances, specic States are identied as examples. In the

section on program costs, for example, potential funding sources are identied, followed by the

State that uses that source (“Fees imposed on all DWI offenders [NM]”). All States identied

in examples are used solely to provide the reader with a reference for further research on the

particular topic under discussion.

Appendices provide the reader with a variety of ready-made resources, from the status of State

programs to frequently asked questions, talking points, detailed checklists, and sample forms.

3

What Is an Ignition Interlock?

Simply stated, an ignition interlock is a device installed on a motor vehicle that requires a breath

sample to determine the driver’s breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) before the vehicle can

start. It does so by requiring the prospective driver to blow into a breath alcohol sensor con-

nected to the vehicle’s ignition system before the vehicle’s engine will start.

An on-board computer analyzes the alcohol concentration of the driver’s breath to determine

if it is below the set point, usually .02 grams per deciliter, before the vehicle will start. If the test

registers above the set point or the person does not provide a breath sample, the interlock will

prevent the vehicle’s engine from starting.

Ignition interlocks are comprised of four basic elements:

1. A breath alcohol sensor installed in the passenger compartment of a vehicle con-

nected to a control unit in the engine compartment that allows the engine to start

only upon an acceptable breath test;

2. A tamper-proof system for mounting the control unit in the engine compartment;

3. A data-recording system that logs breath test results, tests compliance, and other

data required by a State; and

4. A retest system which, after the engine has started, requires the driver to provide

another breath sample to ensure that the driver remains alcohol-free at varying

intervals (such as every 10 to 15 minutes). Manufacturers strongly recommend a

drivers not perform the re-test while the vehicle is in motion, but rather exit trafc

and comply with the test.

3

The installation of an ignition interlock is relatively simple on most vehicles, generally taking no

more than 45 minutes, though it can require up to 2 hours, depending on the individual vehicle

and the experience of the installer.

With all systems in place and operating as intended, the interlock system ensures that the vehicle

cannot be started or driven by a person who has been drinking. Test results and other collected

data provide program administrators with a range of information to monitor offender behavior

during the period that the device is installed.

It is important to note that an interlock device will not interfere with an operating engine. In

the retest, for example, the driver will be required to provide a breath sample while the vehicle

is being operated. In these tests, to ensure safety, several minutes are provided for the driver to

move to a safe location in order to take the test. If a breath sample isn’t provided or the sample

exceeds the set point, the device will warn the driver and activate an alarm (e.g., horn blowing,

lights ashing) that will continue until the ignition is turned off or an acceptable breath sample

is provided.

Summary of Interlock Development

Ignition interlocks have been employed in the United States for more than two decades, with

their use currently proscribed by each State’s laws and regulations.

The rst interlock devices used semiconductor alcohol sensors. This technology was not alcohol-

specic, resulting in frequent false positives and requiring frequent maintenance. Technology

development shifted in the early 1990s from semiconductor sensors to fuel cell technology, the

3

Robertson, 2006

4

same as employed in many evidential breath test instruments used today. Fuel cell ignition inter-

locks are specic to alcohol, retain their calibration longer under normal operating conditions,

and require less maintenance than do their predecessors.

In the early stages of ignition interlock technology development, the National Highway Trafc

Safety Administration issued “Model Specications for Breath Alcohol Ignition Interlock

Devices” (hereinafter referred to as Model Specications), containing recommended perfor-

mance standards and data-recording systems to render tampering or circumvention efforts both

more difcult to undertake and easier to identify.

4

NHTSA has not developed a conforming

products list of devices that meet the specications. Building on NHTSA’s Model Specications,

States have developed their own performance standards and specications. On May 8, 2013,

NHTSA published revised Model Specications for BAIIDs in the Federal Register, revising

the 1992 Model Specications.

5

Current technology development seeks to reduce an operator’s ability to circumvent the system;

increase system tamper resistance; and document each breath test via in-vehicle cameras to

ensure that the offender is the individual providing the breath sample. Other recent develop-

ments include software enhancements and expansion of the types of data that can be collected.

4

Model Specications for Breath Alcohol Ignition Interlock Devices, 1992.

5

National Highway Trafc Safety Administration, 2013.

5

Ignition Interlock Research

Numerous research efforts have been conducted over the past 20 years concerning various

aspects of ignition interlocks, from their value in reducing recidivism to offender compliance

and long-term effects after interlocks have been removed. Highlights of the research are pre-

sented below.

Effects on DWI Recidivism

Research provides strong evidence that, while installed on an offender’s vehicle, interlocks

reduce recidivism among both rst-time and repeat offenders. This includes high-risk offenders,

i.e., those who repeatedly drive after drinking with high BACs, and are resistant to changing

behavior.

6

Once ignition interlocks are removed from a vehicle, however, recidivism rates of ignition inter-

lock users increase and resemble the rates for offenders for whom interlocks were not required.

7

Interlocks and First Offenders. Research projects studying unique offender populations, dif-

ferent measures of recidivism, and varying evaluation periods concluded that ignition interlock

devices are effective in reducing recidivism of rst-time DWI offenders.

8

Interlocks and Repeat Offenders. A number of studies have examined repeat DWI offend-

ers and ignition interlocks, concluding that interlocks reduced subsequent DWI behavior by

those offenders while the interlock was installed on the vehicle.

9

The record of breath tests logged into an ignition interlock has been effective in predicting the

future DWI recidivism risk. Offenders with higher rates of failed BAC tests have higher rates of

post-ignition interlock recidivism.

10

Compliance Rates and Circumvention

When ignition interlock programs were in the early stages of implementation, many drivers

ordered to install an ignition interlock continued to drive without installing the device for a

variety of reasons, ranging from the cost of installation and monthly fees to a lack of vendors/

service providers

11

or monitoring and offender claims of lack of vehicle ownership.

12

Over time,

this has been remedied to some extent through increases in vendors and facilities, and better

offender monitoring (e.g., online data reporting) and the imposition of additional sanctions for

non-compliance.

6

EMT Group 1990; Popkin et al., 1992; Morse & Elliot, 1992; Jones, 1993; Tippetts & Voas, 1997;

Weinrath, 1997; Beirness et al., 1998; Coben & Larkin, 1999; Vezina, 2002; Voas & Marques,

2003; Tashima & Masten, 2004; Willis et al., 2005.

7

Jones, 1993; Popkin et al., 1993; Coben & Larkin, 1999; Beirness, 2001; Marques et al., 2001;

DeYoung, 2002; Raub et al., 2003.

8

EMT Group, 1990; Morse & Elliot, 1992; Tippets & Voas, 1998; Voas et al., 1999; Voas et al.,

2005; Marques et al., 2010; McCartt et al., 2012.

9

Jones, 1993; Popkin et al., 1993; Beirness et al., 1998; Beck et al., 1999; Coben & Larkin, 1999;

Beirness, 2001; Marques et al., 2001; DeYoung, 2002; Raub et al., 2003.

10

Marques & Voas, 2008.

11

The terms “interlock installers,” “service providers,” and “vendors” all refer to those companies

operating in a State to carry out aspects of the ignition interlock program devices themselves, in-

cluding calibration and certication, installation, maintenance and removal, data recording, etc.

For ease of reference, this document will use the term “vendor” when referring to such compa-

nies.

12

DeYoung, 2002; Marques et al., 2010.

6

Offenders who do install interlocks often attempt to circumvent the device during the rst few

weeks after installation by tampering with the breath sample or attempting to disconnect the

device itself from the vehicle’s starter. Research indicates that over time, tampering with the

device decreases.

13

This occurs because offenders learn about the system and recognize their

inability to successfully circumvent it. They also come to understand that tampering attempts

are recorded, resulting in the receipt of additional sanctions for the tampering violation.

Offenders can circumvent an interlock sanction simply by driving another vehicle not equipped

with an interlock device. To remedy this problem, some States have established vehicle usage

criteria when offenders are ordered to install an interlock (e.g., the average number of miles an

offender would be expected to drive to and from work on a weekly basis). If it is subsequently

determined that the vehicle with the ignition interlock has not been driven the expected num-

ber of miles, the State can further sanction the offender if there is no justication for the low

mileage.

Removal of an Interlock at Completion of the Sanction

While studies consistently demonstrate that interlocks reduce recidivism while the device is

installed in an offender’s vehicle, the research also indicates that once the device is removed,

recidivism rates increase to levels comparable to those offenders who were not required to have

an interlock installed as part of their sanction.

14

As a consequence, several studies suggest that

interlocks may be necessary as a long-term or permanent prerequisite for driving for repeat

offenders.

15

Support for Interlocks

Surveys of DWI offenders have found that the majority believed that, even though they may

have disliked having an interlock installed, the sanction was fair and that the interlock reduced

driving after drinking.

16

Families of offenders with ignition interlocks were in favor of the tech-

nology indicating that, while the devices were an inconvenience, they provided a level of reassur-

ance that the offender was not driving while impaired.

17

Other benets to the interlock sanction

include the ability for offenders to continue to drive to work, appointments, family activities,

etc., without disruptions or incurring the added cost and time of alternate transportation.

Interlocks and Substance Abuse Treatment

Research has suggested that the effectiveness of an interlock can be increased when combined

with substance abuse treatment.

18

States that include substance abuse counseling in the sanc-

tioning of DWI offenders could make use of interlock data to facilitate that treatment. For

example, offenders who have a high number of early morning lockouts (i.e., vehicle will not start

because the BAC reading is above the set point) are frequently still intoxicated from the prior

evening’s drinking, information that could be used by a counselor to demonstrate consequences

of heavy drinking. Further, objective data regarding an offender’s alcohol use through monitor-

ing reports can counter an offender’s denial of drinking during the treatment process.

13

Marques et al., 2010.

14

Jones, 1993; Popkin et al., 1993; Beirness et al., 1998; Coben & Larkin, 1999; Marques et al.,

1999; Marques et al., 2001; Beirness, 2001; DeYoung, 2002; Raub et al., 2003; Marques et al.,

2010.

15

DeYoung 2002; Rauch & Ahlin 2003; Raub et al., 2003; Beirness et al., 2003.

16

Roth, 2005; Marques et al., 2010.

17

Beirness et al., 2007; Marques et al., 2010.

18

Baker et al. 2002; Marques et al. 2003a, 2003b

7

Interlock Program Implementation

All States have passed legislation requiring or permitting the use of ignition interlocks, and pro-

grams have been implemented to varying degrees across the Nation based on State legislation

and administrative regulation.

Today’s programs vary in many respects—from how the program is mandated to vendors who

install and service the devices, offender eligibility, and type and frequency of data collected.

The considerations described in this section identify key elements in designing or enhancing an

interlock program within parameters established by State law and regulation.

Benets of an Ignition Interlock Program

Ignition interlocks, when appropriately used, prevent alcohol-impaired driving by DWI offend-

ers, resulting in increased safety for all roadway users. There are other benets to ignition inter-

locks, however, that enhance their value.

Reduction in Recidivism. Research has shown that, while installed on an offend-

er’s vehicle, ignition interlocks reduce recidivism among both rst-time and repeat

DWI offenders.

19

Legal Driving Status. Ignition interlocks permit offenders to retain or regain legal

driving status, thus enabling them to maintain employment and manage familial

and court-ordered responsibilities that require driving. This is a particularly relevant

benet, as many offenders without interlocks drive illegally on a suspended/revoked

license, often after drinking.

20

The installation of an interlock on the offender’s vehi-

cle reduces the probability of this occurring, thereby improving public safety.

Offenders and Families Approve. A majority of offenders surveyed believe igni-

tion interlock sanctions to be fair and reduce driving after drinking.

21

Family mem-

bers believed that ignition interlocks provided a level of reassurance that an offender

was not driving while impaired and reported a generally positive experience and

impact on the offender’s drinking habits.

Predictor of Future DWI Behavior. The record of breath tests logged into an

ignition interlock has been found to be an excellent predictor of future DWI recidi-

vism risk.

22

Offenders with higher rates of failed BAC tests have higher rates of post-

ignition interlock recidivism, information that could be critical regarding whether to

restore an offender’s license, and any conditions under which such action may occur.

Cost Effectiveness. As with any sanction, there are costs. Most administrative

costs (i.e., those costs associated with managing the interlock program) are absorbed

by the State. Costs associated with the devices themselves, including installation,

maintenance, monitoring, estimated at approximately $3 to $4 per day, are borne by

the offender. Research has estimated a cost/benet of an ignition interlock sanction

at $3 for a rst time offender, and $4 to $7 for other offenders accruing for each dollar

spent on an interlock program.

23

The cost of an interlock sanction is less than incar-

ceration, vehicle impoundment, or other monitoring devices such as alcohol monitor-

ing bracelets, with the costs accruing to the offender through a series of fees rather

19

Marques & Voas, 2010.

20

Roth Voas, & Marques, , 2007.

21

Roth, 2005; Marques et al., 2010.

22

Marques et al., 2010.

23

Miller, 2005; Roth et al., 2007.

8

than the State. As interlock programs mature and more offenders are added into the

program, the cost/benet ratio should improve.

Substance Abuse Treatment. A number of States require the installation of an igni-

tion interlock as a nal step toward an unrestricted driving privilege after DWI con-

viction, sometimes combined with substance abuse treatment. In these instances, the

data collected by the interlock can provide treatment providers with current, objec-

tive information regarding the offender’s behavior, which should result in a better

treatment outcome. The combination of an interlock and treatment provides a benet

for the public, in that counseling based on objective data from the interlock’s records

rather than subjective information provided by the offender should have a more posi-

tive effect on the offender, resulting in an increased probability of a reduction in

recidivism.

Types of Interlock Programs

24

Interlock programs in the U.S. have evolved on a State-by-State basis, consistent with each

State’s impaired driving laws and regulations. In spite of the variety of means by which they

have developed, interlock programs can be grouped into three categories:

Administrative. A department of motor vehicles or similar agency requires the

installation of an interlock device as a condition of licensing for a suspended driver,

for license reinstatement. ( CO, IL, MN)

Judicial. The courts mandate an interlock device for offenders, either pre-trial or

post-conviction ( IN, NY, TX)

Hybrid. These programs include features of both the administrative and judicial

approaches (FL, MD, OK)

The advantage of administrative or license-based programs is that they are more uniformly

applied to offenders throughout a jurisdiction, resulting in the likelihood of higher installa-

tion rates. There are a potentially smaller number of agencies and departments involved in an

administrative program, streamlining the processes and making it more cost effective.

The advantage of the judicially administered program is that the courts have the legal authority

to ensure compliance and may better monitor offenders utilizing an established system to track

offenders. Court-administered programs are also able to require pre-trial interlock use, impose

additional sanctions for noncompliance or tampering with the interlocks, and mandate offender

participation in substance abuse treatment programs.

The hybrid approach can incorporate the strengths of both the administrative and judicial

systems within the State’s legal framework, thereby developing a more efcient and effective

program. However, hybrid programs face the challenge of coordination between the adminis-

trative and judicial systems, as well as a potential for increased costs associated with the involve-

ment of a larger number of governmental entities.

Interlock Programs: Getting Started

All States currently have ignition interlock laws, and nearly all have ignition interlock pro-

grams. These programs are in various stages of implementation and have met with varying

levels of success. Proper planning is essential in developing and rening these programs. The

following should be included in planning ignition interlock programs.

24

Trafc Injury Research Foundation, 2009.

9

Program Goals

25

The rst step in designing a successful program is to identify the primary purpose for the igni-

tion interlock component of the State’s overall impaired driving program. This is essential in

establishing the goals and objectives

of the interlock program in support of

the larger effort.

The primary methodology used in an

interlock program is incapacitation,

that is, separating the impaired driver from the vehicle. Drivers sanctioned to an ignition inter-

lock is only able to start and drive a vehicle when their BAC is below the set point. The ignition

interlock, by preventing the offender from driving the vehicle after drinking, will reduce the

likelihood of the offender from becoming a danger to himself, passengers, and other roadway

users—a key program goal.

There are, however, several overarching goals a successful program should consider:

Punishment. The offender suffers the punishment of having an interlock installed.

While it is a less onerous punishment than jail or home connement, it serves as a

continual reminder to the offender of the crime committed since the offender is, in a

sense, incapacitated (e.g., cannot drink and drive), and reinforces the fact that there

are serious consequences for violating the law. The stigma of having the device on the

motor vehicle, providing a breath sample to start the vehicle (often in front of family

and friends), having to take time off work for routine servicing, having data collected

on many aspects of an offender’s activities, all contribute to the punishment of each

offender with an interlock sanction.

Deterrence. The thrust of deterrence in impaired driving programs is to discourage

people from drinking and driving by imposing a series of specic consequences—

including, in this case, an interlock—on those convicted of DWI. Informing and

educating the community that interlocks are part of the sanctioning process may also

prove an effective general deterrent, as some potential offenders may change their

behavior to avoid arrest and an interlock sanction.

Rehabilitation. An interlock can provide a “teachable moment” for offenders,

motivating them to examine their behavior and providing an opportunity to change.

Depending on specic program goals, this can be accomplished through the simple

act of using the interlock over an extended period of time, or a formalized program

of substance abuse treatment, where offenders are required to combine treatment

with the interlock sanction. In instances of combined substance abuse treatment and

interlock use, the data collected by the device provides valuable objective data to aid

counseling.

A successful interlock program should consider the following goals:

Incapacitation Punishment

Deterrence Rehabilitation

Specic goals identied for the program should be used to dene supporting objectives and pro-

cesses involved in the program, including the identication of participating agencies, workow,

25

TIRF, 2009.

Conceivably, the best way to structure interlock programs is

to impose on offenders a level of monitoring restriction that

matches the level of public risk they represent.

Marques et al., 2010.

10

resources. The goals will also serve as the basis for the policies that dene program participa-

tion, non-compliance, and more.

Stakeholder Involvement

State experience has demonstrated the value of identifying and engaging key stakeholders early

in the ignition interlock program development process. At a minimum, each of the agencies

responsible for implementing any of

the tasks associated with the inter-

lock program should participate in

planning, since their capabilities,

cost implications and needs must

be taken into account in developing

operational plans that will meet pro-

gram goals, while identifying poten-

tial problems that will need to be

addressed.

Additionally, it is advisable to establish a subset of the stakeholder work group to assist with edu-

cational and outreach opportunities, and to engage professional associations and community

groups in understanding and supporting the interlock program’s goals and the importance of

reducing impaired driving.

Potential Stakeholders

Legislators and policy makers • State highway safety ofces • Law enforcement ofcials,

Law enforcement liaisons • Judges • State licensing agencies • Prosecutors • Defense

attorneys • Probation personnel • Trafc safety resource prosecutors • Judicial outreach

liaisons • Toxicology laboratory authorities • Alcohol and drug

treatment personnel • Ignition interlock vendors

Program Planning

The steps involved in designing an ignition interlock program are no different than the plan-

ning required for any major initiative. Once stakeholders have been identied and invited to

participate, the process is relatively straightforward.

Depending on the number of participants on the planning group, it is advisable to create a

steering committee and work groups to deal with specic aspects of the program (e.g., legislative

review, vendor/device certication, data collection, monitoring, evaluation, communications/

publicity).

26

Establish program goals and objectives. These goals and objectives will dene

the ultimate outcomes of the interlock program. Having the goals in mind will ensure

that the appropriate chain of authority and communications channels are established

during the planning process.

Include provisions for evaluation and communication in early planning.

Evaluation, and communications and public information/education components of

a program should relate directly to the established goals. In some instances baseline

data will need to be collected to allow for the program to be evaluated once estab-

lished. The program goals will need to be communicated to participants, stakehold-

ers, and the public early in the process. A well-planned communications strategy will

26

Spratler, 2009; GHSA, 2010.

Form an inclusive committee of stakeholders to plot the course of

a State’s interlock program, including the State highway safety

ofce, the DMV, interlock vendors and even other representa-

tives from States with interlock experience.

Mimi Kahn

Deputy Director, CA DMV

National Ignition Interlock Summit

November 2010

11

ensure that all are aware of the purpose and value of the program, and questions

can be asked and concerns addressed early in the implementation process. Public

awareness and education of the program’s goals and objectives will help ensure its

acceptance. If these components are not included, a valuable opportunity will be lost.

Develop clear and concise administrative rules. These rules should detail the

following.

S The specic agency that will have overall responsibility for the ignition interlock

program

S Chain of authority

S Functions to be performed and by whom

S Vendor oversight

§

Licensing and certication

§

Monitoring and reporting

S Offender participation

§

First, high-BAC or multiple offenders

§

When the sanction will take effect (immediately upon conviction, in lieu of or

after license suspension)

§

Requiring interlocks for offenders having a hardship license

§

Mandatory installation for re-licensing

§

Length of interlock sanction

§

Minimum vehicle use requirements

§

Relation to substance abuse treatment

§

Restriction added to the driver’s license

S Handling non-compliance

§

Repeated BAC lockouts

§

Procedural failures (e.g., not taking retests)

§

Circumventing/tampering with the device

S Linkage to substance abuse treatment

§

Eligible offenders

§

Use of data to assess offender progress

Develop process ow charts. Charting all agencies and ofces involved in the

program will assist in eliminating overlap or redundancy while ensuring that part

of the process is not overlooked. The ow chart will help establish chains of author-

ity and accountability, and will begin to shed light on resources (staff, equipment,

funding) and training that may be required among the various agencies and ofces

involved in program implementation.

Plan for interstate coordination and collaboration. Today’s society is

extremely mobile, leading to the strong possibility that potential offenders could reg-

ularly cross State lines, traveling to work, vacations, and other destinations. It is also

possible an offender convicted of DWI in one State is a resident of another. This could

12

lead to a variety of challenges regarding the installation, servicing and monitoring

of use of an interlock. It is also possible that, to provide increased access to vendors

in rural areas, one State’s vendor might be located in a neighboring State. To ensure

appropriate program oversight and reduce the potential for problems, it is important

to develop plans to establish reciprocity and address coordination with neighboring

States early in the process. Include the plans as part of vendor selection and oversight.

Review current legislation/regulations. Eliminate redundancy, overlap or

conicts, and loopholes.

Because of the complexities of even the most simple and

straightforward ignition interlock program, it is important that sufcient

time be allocated to the planning stage.

Vendor Selection and Oversight

27

There are a number of interlock manufacturers and vendors currently doing business in the

United States, providing a variety of management models and technology options for the States.

When deciding on vendors that will be approved for a State’s program, policy makers must

thoroughly review and prioritize a range of issues, from their facilities and operations to tech-

nology options, in relation to the program’s requirements.

NHTSA’s Model Specications for breath alcohol ignition interlock devices provide recom-

mended performance standards and data-recording systems for the devices themselves.

Individual States, however, have rened operational and data requirements for interlock devices

certied for use to meet State-specic program goals and objectives.

In developing requirements, it is imperative that a State’s requirements

and expectations are specic and clearly spelled out for the vendors.

The States currently employ a variety of vendor oversight models. The following should be

considered when planning vendor management.

28

Free-market contracting and multiple providers (MD) versus limited (FL) or even a

sole provider (HI).

The geographic distribution of vendors, particularly in rural areas, so all offenders

can be easily served.

Reciprocity, coordination, and collaboration with adjoining States for the installation

and monitoring of offenders or transient violators. (OK, NY)

Certication of vendors and devices as well as vendor inspection and monitoring.

De-licensing or de-certication procedures for vendors that fail to comply with State

requirements and regulations.

Provisions for interlock override capability for routine maintenance of the interlocked

vehicle (i.e., when the vehicle is taken to a dealer for servicing).

27

Robertson, Holmes, & Vanlaar, 2011.

28

Appendix E: External Relationships with Vendors/Service Providers, contains a detailed checklist to assist

in developing effective vendor management and oversight programs.

13

The type of data collected, format in which it is reported, and frequency with which

it is reported.

It is important that vendor oversight be manageable and achievable. When vendors are involved

in the planning process, the oversight plan has a better likelihood of success. After the plan has

been nalized and vendors selected, meetings between program staff and vendors should rou-

tinely take place to ensure the plan is working, and to address problems as they arise.

When licensing and certifying multiple vendors, a common set of

attainable reporting requirements should be developed so program

administrators can track the number of interlocks installed in

offenders’ vehicles, monitor the provision of interlock services, and

easily compare data provided by all vendors.

Offender Monitoring and Reporting

Most ignition interlocks collect and record a signicant amount of information each time the

interlock is accessed. Data related to vehicle use, driver alcohol use, and attempts to circumvent

the technology provide important information for driver control and sanctioning authorities,

ensuring offenders comply with the program and identifying noncompliant offenders who will

require more intensive supervision and, perhaps, the imposition of additional nes/sanctions.

Using the data to monitor offender behavior is critical to the effectiveness of the program and,

ultimately, roadway safety.

Reporting standards and a system for the transfer of data from

vendors to program administrators must be developed during initial

planning. What is required, why it is required, and how it will be used

are all important considerations in developing reporting standards.

Data elements require clear, consistent denitions. Different vendors may have differing de-

nitions for “circumvention” of a device, for example, or activity that results in a “violation.”

To ensure consistency in the data that is compiled and delivered by the range of vendors and

devices that may be in use in a State, it is imperative that all vendors are absolutely clear on the

denition of the data they are to collect, and all those who will be using the data understand

the denition

State standards should include a set of clear denitions with respect to

all data collection and reporting terms.

All interlock devices are designed to capture the following date/time-stamped data, in addition

to offender and vehicle information, mileage, and date of servicing.

All breath tests (initial and retests)

Failures to submit to a breath test

Each time the vehicle is turned on/off

Tampering and circumvention attempts

Failure to turn the vehicle off following a failed test

14

The time period the vehicle was driven

Mileage driven

Vehicle lockouts and/or early recalls

29

Use of the emergency override feature (when activated)

If a State does not capture all available data, the most important data to collect, in addition to

the offender and vehicle information, mileage, and date of servicing, includes:

Alcohol positive breath tests (e.g., those above the set point),

Failure to submit to a breath test,

Tampering and circumvention attempts,

Vehicle lockouts and/or early recalls, and

Use of the emergency override feature (when available and activated).

Offenders must be made aware that they will be monitored (the data collected and frequency of

reporting) and the consequences for violating the established protocol. Monitoring provides the

impetus to “reward” an offender for continued good behavior or adds sanctions to those who

continue to attempt to drink and drive or circumvent the system.

As essential as monitoring/reporting is, it is also one of the more difcult aspects of an ignition

interlock program. Lack of clear denition of terms; no clear chain of authority and responsibil-

ity between vendors and program staff; poor communications; lack of training among practitio-

ners; all contribute to the possibility of inconsistent monitoring and reporting, resulting in the

possibility of violations not being identied and violators not receiving the appropriate sanction

for the violation.

Because of this, it is imperative that policies and procedures are put into place during planning

detailing chain of reporting, identifying the agency with the authority to take action against

noncompliant offenders, and the graduated sanctioning that may be taken in response to spe-

cic violations. It is also important that compliant behavior be recognized during monitoring

as a method to encourage positive behavior change.

Accurate and timely data will provide program administrators with

information needed to assess the offender’s compliance with the

sanction and justication for more intense supervision or imposition of

additional nes/sanctions for noncompliant offenders.

In addition to policies and procedures, everyone who will be involved in monitoring must be

sufciently trained to accomplish all tasks for which they will be responsible. Further, pro-

cesses for routine collaboration and coordination between all entities involved with monitoring/

reporting should be established to ensure all violations are quickly identied and offenders

receive the appropriate sanction for the violation.

29

An early recall requires that an interlocked vehicle be taken to the vendor prior to its normal

servicing schedule due to a large number of lockouts (e.g., failed breath tests).

15

Interlock Program Costs

In examining costs associated with an interlock program, there are two areas to consider:

administrative costs and the cost of the device itself.

Administrative costs, including increased workloads and operational systems established to

manage a higher volume of cases, are usually absorbed by the State. However, some States have

established fees, collected from offenders and vendors, to generate revenue.

Costs associated with the interlock devices themselves are usually paid by the offender and

include device installation and maintenance costs, calibration, data collection services, device

failed lockout reset fees, and removal fees when an offender leaves the program.

Potential Sources of Funding

Fees Collected From the Offender

Enrollment

Interlock Installation

Monitoring

Transfer of interlock to a new vehicle

Interlock Reset (running retest refusal, device lockout, tampering)

Interlock removal (at the conclusion of the sanction)

Roadside service call

License reinstatement

Fees Collected From the Vendor

Initial license and certication

Renewal license and certication

Installation service center certication and licensing (and renewal)

Installer training and certication (and renewal)

Average initial installation costs are about $70 to $90. Monthly fees of approximately $70 cover

costs associated with downloading and reporting data captured by the interlock. Assuming that

an offender does not violate the sanction (by circumventing or tampering with the device, for

example) resulting in the payment of additional fees, the daily cost of an ignition interlock aver-

ages about $3 to $4 per day, the cost of a typical drink.

30

Indigent Funds

State programs face the challenge of how to address the problem that some offenders cannot

afford the fees associated with an interlock sanction. To address this, a growing number of

States are developing a special indigent offender fund to help offset costs for those who other-

wise cannot afford an interlock. This has become increasingly important as more States move

to applying an ignition interlock sanction to rst offenders.

30

TIRF, 2009.

16

Sources for indigent offender funds are as varied as the programs themselves, coming from

sources such as

Fees imposed on all DWI offenders,

Fees added to license reinstatement, and

A charge added by vendors to their paying customer’s fees.

To ensure that only truly indigent offenders receive funding assistance, objective criteria must

be developed against which all applicants will be judged. This eliminates bias and reduces the

possibility of fraud.

Sample Indigency Qualifying Criteria

Proof of enrollment in one or more public assistance programs (NM)

Financial Disclosure Report Forms itemizing sources of income and expenses (NY)

Gross income as a percentage of the Federal poverty guidelines (CO)

In establishing an indigent offender fund, the following, at a minimum, should be documented.

The agency responsible for administering the fund

Objective criteria to determine eligibility

Fees to be covered

Penalties for interlock violations by participants

Periodic participant reassessment for continued eligibility

When nalized, brochures should be developed that summarize the indigent offender fund,

document the criteria, itemize fees to be covered, and outline the process to apply for funding

assistance. In addition, an application form should be developed that will be used by all apply-

ing for nancial assistance.

17

References

Baker, S. P., Braver, E. R., Chen, L-H., Li, G., & Williams, A. F. (2002). Drinking Histories of

Fatally Injured Drivers. Injury Prevention 8(3): 221-226.

Beck, K., Rauch, W., Baker, E., & Williams, A. (1999). Effects of Ignition Interlock License

Restrictions on Drivers with Multiple Alcohol Offenses: A Random Trial in Maryland. American

Journal of Public Health 89, 1696-1700.

Beirness, D. J., Simpson, H. M., & Mayhew, D. R. (1998). Programs and Policies for Reducing

Alcohol-Related Motor Vehicle Deaths and Injuries. Contemporary Drug Problems 25, 553-578.

Beirness, D. J. (2001). Best Practices for Alcohol Interlock Programs. Ottawa, ON: Trafc Injury

Research Foundation.

Beirness, D. J., & Marques, P. M. (2004). Alcohol Ignition Interlock Programs. Trafc Injury

Prevention 5(3), 299-308.

Beirness, D. J., Clayton, A., & Vanlaar, W. G. M. (2007). An Investigation of the Usefulness,

the Acceptability and Impact on Lifestyle of Alcohol Ignition Interlocks in Drink Driving

Offenders. Road Safety Research Report No. 88. London: Department of Transport.

Coben, J. H., & Larkin, G. I. (1999). Effectiveness of Ignition Interlock Devices in Reducing

Drunk Driving Recidivism. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 16 (IS), 81- 87.

DeYoung, D. J. (2002). An Evaluation of the Implementation of Ignition Interlock in California.

Journal of Safety Research 33, 473-482.

EMT Group. (1990). Evaluation of the California Ignition Interlock Pilot Program for DWI Offenders

(Farr-Davis Driver Safety Act of 1986). California Ofce of Trafc Safety. Sacramento, CA: The

EMT Group, Inc.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2011). Table 69, Arrests. Crime in the United States. Washington,

DC:.

Fielder, K., Brittle, C., & Stafford, S. (2012). Case Studies of Ignition Interlock Programs. (Report No.

DOT HS 811 594). Washington, DC: National Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

Governor’s Highway Safety Association. (2010). National Ignition Interlock Summit: Summary Report.

Washington, DC:.

Jones, B. (1993). The Effectiveness of Oregon’s Ignition Interlock Program. In: H.D. Utzelmann,

H.D., Berghaus, G., & Kroj, G. (Eds.). Alcohol, Drugs and Trafc Safety, Köln, Germany, 28

September – 2 October 1992. Köln: Verlage TÜV Rheinland GmbH, Vol. 3, pp. 14600-1465.

Marques, P. R., Tippetts, A. S., Voas, R. B., & Beirness, D. J. (2001). Predicting repeat DWI

offenses with the alcohol interlock recorder. Accident Analysis and Prevention 33(5), 609-619.

Marques, P. R., Tippetts, A. S., & Voas, R. B. (2003a). The alcohol interlock: An underutilized

resource for predicting and controlling drunk drivers. Trafc Injury Prevention 4(3): 188-194.

Marques, P. R., Tippetts, A. S., & Voas, R. B. (2003b). Comparative and joint prediction of

DUI recidivism from alcohol ignition interlock and driver records. Journal of Studies on Alcohol

64(1): 83-92.

18

Marques, P. R., & Voas, R. B. (2008). Alcohol Interlock Program Features Survey. Unpublished

survey results from the Interlock Working Group of the International Council of Alcohol Drugs

and Trafc Safety.

Marques, P. R., & Voas, R. B. (2010). Key Features for Ignition Interlock Programs. (Report No. DOT

HS 811 262). Washington, D.C.: National Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

Marques, P. R., Voas, R. B., Roth, R., & Tippetts, A. S. (2010). Evaluation of the New Mexico

Ignition Interlock Program. (Report No. DOT HS 811 410). Washington, DC: National Highway

Trafc Safety Administration.

McCartt, A. T., Leaf, W. A., Farmer, C. M., & Eichelberger, A. H. (2012). Washington State’s

Alcohol Ignition Interlock Law: Effects on Recidivism Among First-Time DUI Offenders. A rling ton, VA:

Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

Miller, T. R., & Hendrie, D. (2005). How Should Governments Spend the Drug Prevention

Dollar: A Buyer’s Guide. In T. Stockwell& P. Gruenewald,, et al. (eds.), Preventing Harmful

Substance Use: The Evidence Base for Policy and Practice. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Model Specications for Breath Alcohol Ignition Interlock Devices (BAIIDs). 57 Federal

Register, 11774-11787. (April 7, 1992). National Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

Model Specications for Breath Alcohol Ignition Interlock Devices (BAIIDs). 75 Federal

Register, 61820-61833. (October 6, 2010). National Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

Morse, B. J. & Elliott, D. S. (1992). Hamilton County Drinking and Driving Study. Interlock Evaluation:

Two Year Findings. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado Institute of Behavioral Science.

National Highway Traf c Safety Administration. (2012). Traf c Safety Facts: Alcohol-Impaired

Driving: 2010 Data. (Report No. DOT HS 811 606). Washington, DC: Author.

Popkin, C. L., Stewart, J. R., Bechmeyer, J., & Martell, C. (1993). An Evaluation of the

Effectiveness of Interlock systems in Preventing DWI Recidivism Among Second-Time DWI

Offenders. In: H.E. Berghaus, & G. Kroj (Eds.). Alcohol, Drugs and Trafc Safety, Köln, Germany,

28 September – 2 October 1992. Köln: Verlage TÜV Rheinland GmbH, Vol. 3, pp. 1466-1470.

Raub, R. A., Lucke, R. E., & Wark, R. I. (2003). Breath Alcohol Ignition Interlock Devices:

Controlling the Recidivist. Trafc Injury Prevention 4, 199-205.

Robertson, R. D., Holmes, E., & Vanlaar, W. (2011). Alcohol Interlocks: Harmonizing Policies and

Practices. Proceedings of the 11th International Alcohol Interlock Symposium. Montebello, QC:

Trafc Injury Research Foundation.

Robertson, R. D., Holmes, E. A., & Vanlaar, W. G. M. (2011). Alcohol Interlock Programs: Vendor

Oversight. Ottawa: Trafc Injury Research Foundation.

Robertson, R. D., Vanlaar, W. G. M., & Simpson, H. M. (2006). Ignition Interlocks From Research

to Practice: A Primer for Judges. Ottawa: Trafc Injury Research Foundation.

Roth, R., Voas, R., & Marques, P. (2007). Interlocks for First Offenders: Effective? Trafc Injury

Prevention 8, 346-352.

Roth, R. (2005). Surveys of DWI Offenders Regarding Ignition Interlock. Anonymous surveys

conducted before Victim Impact Panels in Santa Fe and Albuquerque, NM.

19

Roth, R. (2008). New Mexico Interlock Program Overview. PowerPoint presentation, 10-28-

08. www.drivesoberillinois.org/pdf/Richard%20Roth.pdf.

Roth, R. (2012). 2011 Survey of Currently Installed Interlocks in the U.S. Santa Fe, NM: Impact DWI,

Inc.

Sprattler, K. (2009). Ignition Interlocks – What You Need to Know. (Report No. DOT HS 811 246).

Washington, D.C.: National Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

Tippets, A. S., & Voas, R. B. (1997). The Effectiveness of the West Virginia Interlock Program

on Second Drunk-Driving Offenders. In E. Mercier-Guyon (Ed.). Alcohol, Drugs and Trafc Safety

– T97. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Alcohol, Drugs and Trafc Safety, Annecy,

France, September 21-16, 1997. Annecy: CERMT, Vol. 1, pp. 185-192.

Tippets, A. S. & Voas, R. B. (1998). The Effectiveness of the West Virginia Interlock Program.

Journal of Trafc Medicine 26, 19-24.

Trafc Injury Research Foundation. (2009). Alcohol Interlock Curriculum. Ottawa: Trafc Injury

Research Foundation.

Vezina, L. (2002). The Quebec Alcohol Interlock Program: Impact on Recidivism and Crashes.

In D. R. Mayhew & C. Dusault (Eds.). Alcohol, Drugs and Trafc Safety – T2002. Proceedings of the

16th International Conference on Alcohol, Drugs and Trafc Safety. Montreal, August 4-9, 2002. Quebec

City: Societe de l’assaurance automobile du Quebec, pp. 97-104.

Voas, R. B., Marques, P. R., Tippetts, A. S., & Beirness, D. J. (1999). The Alberta Interlock

Program: The Evaluation of a Province-wide Program on DUI Recidivism. Addiction 94(12),

1849-1859.

Voas, R. B. & Marques, P. R. (2003). Commentary: Barriers to Interlock Implementation.

Trafc Injury Prevention 4(3). 183-187.

Voas, R. B., Roth, R., & Marques, P. R. (2005). Interlocks for First Offenders: Effective? Global

Perspective. Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Alcohol Ignition Interlock Programs, Annecy,

France, September 25-27, 2005, pp. 7-8. Ottawa: Trafc Injury Research Foundation.

Voas, R. B. & Marques, P. R. (2007). History of Alcohol Interlock Programs: Lost Opportunities

and New Possibilities. Proceedings of the 8th Annual Ignition Interlock Symposium, August. 26 –27, 2007,

Seattle, WA.

Weinrath, M. (1997). The Ignition Interlock Program for Drunk Drivers: A Multivariate Test.

Crime and Delinquency 43(1). 42-59.

Willis, C., Lybrand. S., & Bellamy, N. (2004). Alcohol Interlock Programmes for Reducing

Drink Driving Recidivism (Review). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4).

20

Resources

The documents and Web sites identied below provide the

reader with additional information on ignition interlock program

implementation and administration.

Association of Ignition Interlock Program Administrators. A new organization designed to

provide “leadership to the ignition interlock device community by promoting best practices,

enhancing program management, and providing technical assistance to improve trafc safety

by reducing impaired driving.” http://aiipa.org/.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Reducing Alcohol-Impaired Driving: Ignition Interlocks.

www.thecommunityguide.org/mvoi/AID/ignitioninterlocks.html.

Fielder, K., Brittle, C., & Stafford, S. (2012). Case Studies of Ignition Interlock Programs. (Report No.

DOT HS 811 594). Washington, DC: National Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

Governor’s Highway Safety Association. (2010). National Ignition Interlock Summit: Summary Report.

www.ghsa.org/html/meetings/interlock.html.

MADD. Ignition Interlocks. www.madd.org/laws/ignition-interlock.html. This website provides

an overview of MADD’s position on interlocks, fact sheets, frequently asked questions, and

additional reference materials.

MADD. Annual Survey of Currently Installed Ignition Interlocks. www.madd.org/blog/2012/august/

annual-survey-of-IID.html.

NHTSA Reports No. DOT HS 811 262, Key Features for Ignition Interlock Programs, and DOT HS

811 410, Evaluation of the New Mexico Ignition Interlock Program. (See references above.)

McCartt, A.T., Leaf, W.A., Farmer, C.M., & Eichelberger, A.H. (2012). Washington State’s Alcohol

Ignition Interlock Law: Effects on Recidivism Among First-time DUI Offenders. Arlington, VA: Insurance

Institute for Highway Safety.

National Center for DWI Courts. Ignition Interlock Guidelines for DWI Courts. www.dwicourts.

org/search/apachesolr_search?keys=ignition+interlocks&submit=Go. This site provides cur-

rent State legislation, guidelines regarding interlock programs for DWI courts and identies

additional resources.

National Conference of State Legislators. State Ignition Interlock Laws. http://www.ncsl.org/

issues-research/transport/state-ignition-interlock-laws.aspx/.

Trafc Injury Research Foundation.

Alcohol Interlock Curriculum. http://aic.tirf.ca.

Alcohol Interlock Programs: Vendor Oversight. www.tirf.ca/publications/PDF_ publications/

NHTSA_Tech_Assistance_VendorReport_4_web.pdf.

Ignition Interlocks From Research to Practice: A Primer for Judges.

The Implementation of Alcohol Interlocks for Offenders: A Roadmap. www.tirf.ca/publica-

tions/PDF_publications/CC_2010_Roadmap_2.pdf.

21

Appendix A: Frequently Asked Questions

Ignition Interlocks

: Q What is an alcohol ignition interlock?

An alcohol ignition interlock is a device installed on a motor vehicle that is connected to the

ignition system. A driver is required to provide a breath sample to verify that the person seeking

to operate that vehicle does not have a breath alcohol concentration above a specied limit or

set point, usually .02 grams per deciliter. An interlock is comprised of a breath alcohol sensor,

typically installed on the vehicle’s dashboard, a control unit connected to the vehicle’s starter or

ignition, and a data collection system.

When an alcohol-free breath sample is given and veried by the interlock system, the ignition

interlock will provide power to the vehicle. If the breath test registers above the set point or a

person does not provide a breath sample, no power will reach the starter circuit, preventing the

vehicle from starting.

At random times after the engine has been started, the device will require the driver to provide

another breath sample, called a retest. In these instances, the driver is given several minutes to

exit trafc and move to a safe location to take the test. If the breath sample isn’t provided or the

sample exceeds the set point, the device may warn the driver and activate an alarm (e.g., horn

blowing, lights ashing) that will continue until the ignition is turned off or a breath sample that

is within the acceptable limits is provided. For safety reasons, the interlock device cannot turn

off the vehicle’s ignition once it has been started.

An alcohol ignition interlock’s software system logs test results and records other data, such as

number of times a vehicle is turned on and off, mileage driven, and attempts to circumvent

or tamper with the device, providing program administrators with a range of information to

monitor offender behavior during the period that the device is installed.

: Q Can an offender bypass using the ignition interlock device?

Ignition interlocks currently on the market have anti-circumvention features designed to pre-

vent an offender from bypassing the device. Pressure and temperature sensors, in-vehicle cam-

eras to video the breath test, retests, and the ability to record all events related to the vehicle

use, have thwarted many of the methods offenders previously used to try to circumvent igni-

tion interlocks. Further, attempts to circumvent the interlock are recorded and offenders can

have additional fees and sanctions added to their sentence, reducing the incentive to attempt

to thwart the device. Some ignition interlock models contain an override feature as an option,

allowing a driver to be able to start the vehicle without taking a breath test, to be used only in

emergency situations. It is important that, if this feature is included on the interlock, the data

recorder continue to function as normal, recording all data routinely collected (e.g., mileage,

length of time the vehicle was driven) so that it can be compared with the explanation provided

by the driver. To prevent misuse of this feature, additional requirements to a driver’s sanction,

such as servicing following each use of the emergency override and extending the time the

device is on the vehicle, should be required.

There is also the possibility that offenders will attempt to avoid interlock installation by claim-

ing they do not own a vehicle or that they do not drive, or simply by driving another vehicle. To

encourage interlock use, States can employ incentives (e.g., shorter license suspension with an

interlock, reduced nes and fees), increase offender follow-up and monitoring to ensure inter-

locks are installed, or increase sanctions for offenders who do not install or use the device.

22

Some States have established vehicle usage criteria (e.g., the average number of miles an offender

would be expected to drive to and from work on a weekly basis) when offenders are ordered to

install an interlock. If it is subsequently determined that the vehicle with the ignition interlock

has not been driven the expected number of miles, the State can further sanction the offender

if there is no justication for the low mileage.

: Q What happens if an offender takes medicine with an alcohol base

or uses an alcohol-based mouthwash?

Alcohol is alcohol. If the BAC found in the breath sample exceeds the set point, the vehicle will

not start. In the case of mouthwash containing alcohol, if the driver waits several minutes for the

mouth alcohol to dissipate and then takes a retest, the vehicle should start.

: Q What happens when an offender tries to start a vehicle after

drinking alcohol?

The ignition interlock will enter a short lockout period of a few minutes for the rst failed test,

followed by a longer lockout for any subsequent test. This permits an opportunity for the alco-

hol to dissipate from the mouth and allow the driver to consider the reason for the failed test. If

subsequent tests are not passed, the vehicle will not start.

: Q How do ignition interlocks affect the offender’s family?

Anyone using a vehicle with an ignition interlock must blow into the device for the vehicle to

start. In spite of the inconvenience, most family members favor interlocks, as they maintain

order in the family: the offender can continue to drive to work and appointments, and chil-

dren can be driven to school and other activities. The alternative, losing the driving privilege,

can be very disruptive to a family. It can result in the offender losing his or her job due to lack

of transportation, family members having to provide the offender transportation to work and

appointments, or the offender violating additional laws (driving without a license, driving while

impaired, etc.).

Reliability and Effectiveness of Ignition Interlocks

: Q How reliable are ignition interlocks?

The NHTSA Model Specications, rst adopted in 1992, provide that an ignition interlock

must prevent a vehicle from starting 90 percent of the time the BAC is .01 g/dL greater than the

set point (.02 g/dL in extreme weather conditions).

31

Using the Model Specications as a start-

ing point, individual States have developed performance standards for devices eligible for use in

the State. On May 8, 2013, NHTSA published revised Model Specications for BAIIDs in the

Federal Register (78 Fed. Reg. 26849), revising the 1992 Model Specications.

: Q How effective are ignition interlocks?

Research has demonstrated that many alcohol-impaired drivers continue to drive illegally

regardless of the fact that their driver’s license has been suspended or revoked. An ignition

interlock is designed to prevent that by permitting an offender to continue to drive so long as

he/she passes the interlock’s breath test. Ignition interlocks effectively deter impaired driving

while they are on the offender’s vehicle. In fact, recidivism is reduced by 50 to 90 percent while

the device is installed.

: Q Are ignition interlocks effective for rst-time and repeat DWI

offenders?

Research shows that an ignition interlock on an offender’s vehicle keeps both rst-time and

repeat DWI offenders from driving after drinking while it is installed on the vehicle.

31

Model Specicaons for Breath Alcohol Ignion Interlock Devices, 1992.

23

Interlock Programs

: Q How are ignition interlock programs administered?

There are currently three types of ignition interlock programs used in the United States:

Administrative. A State licensing authority or similar agency requires the instal-

lation of an interlock device as a condition of licensing for a suspended driver, for

license reinstatement, etc.

Judicial. The courts mandate an interlock device for offenders, either pre-trial or

post-conviction.

Hybrid. A combination of the administrative and judicial approaches.

The fundamental difference between the rst two is that State licensing authorities are more

likely to order the use of interlocks, while judges that order interlocks can more effectively

enforce the interlock requirement. The hybrid approach seeks to combine the best attributes of

each of the other types for a more comprehensive and effective program.

: Q Who is eligible to have an ignition interlock installed?

Ignition interlock laws exist in all States, and those States with active interlock programs admin-

ister them through several means: administratively (through a department of motor vehicles

or similar agency), judicially (through court mandate), or a hybrid approach (a combination of

elements of the administrative and judicial approach). Generally, interlock eligibility is either

required or provided in one of four ways:

1. A voluntary option for some offenders in return for a shorter license suspension;

2. A requirement by an individual judge as a condition of probation;

3. A requirement by State law for some or all repeat or high BAC (usually .15 g/dL or

above) offenders as a condition of license reinstatement; or

4. A requirement by State law for all offenders as a condition of license reinstatement.

See. Appendix B: State Ignition Interlock Laws, Regulations, and Program

Information, for a listing of eligible offenders by State.

: Q How much do interlocks cost?

While installation of an ignition interlock varies by vendor, features, and region of the country,

they generally cost between $70 and $90 to install. In addition, there are monthly monitoring

fees and a removal fee required at the conclusion of the sanctioning period. If an offender does

not violate the sanction by failing a test or attempting to circumvent or tamper with the device,

which can result in additional fees, the average daily cost is $3 - $4, or about the cost of a typical

drink.

: Q What if the offender is unable to afford the cost?

While most States require that the entire cost of an ignition interlock sanction be paid by the

offender, more and more States are establishing an indigent offender fund to cover a portion (or

all) of the costs associated with installation, monitoring and servicing for qualifying offenders.

In these cases, specic criteria dene “indigent,” ensuring that non-indigent offenders are not

able to take advantage of the program.

See Appendix B: State Ignition Interlock Laws, Regulations, and Program

Information for a listing of those States that maintain an indigent offender fund.

24

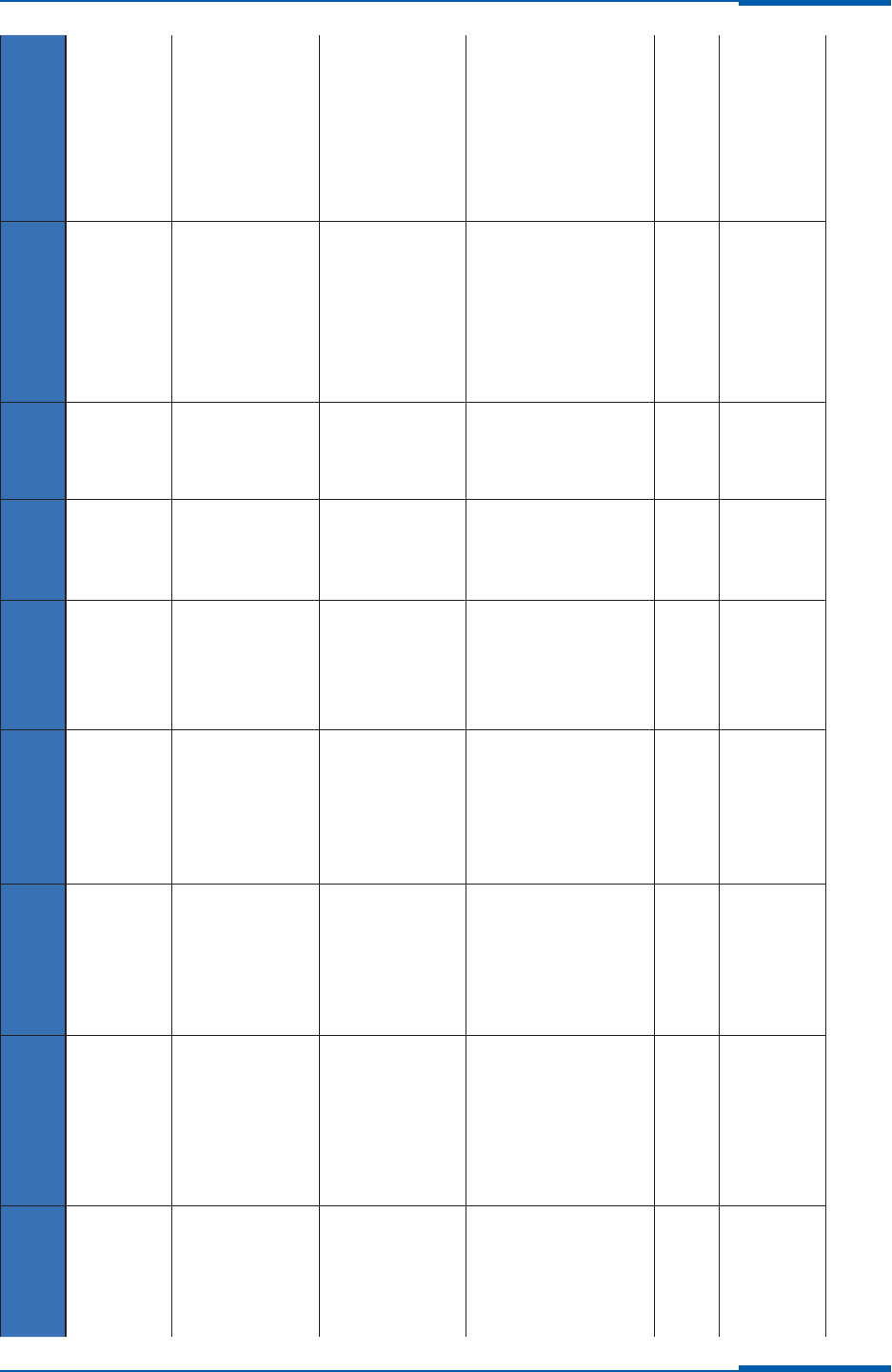

Appendix B: State Ignition Interlock Laws, Regulations,

and Program Information

This appendix is intended for informational and educational purposes only, and is not intended

to provide legal advice. Laws, regulations and policies vary not only by State but also by local

jurisdiction. Therefore, it is important to seek out legal advice from a licensed attorney on spe-

cic issues or questions you may have. For your reference, we have compiled a State-by-State list

of ignition interlock laws, regulations and program information. Please note that information

may have changed since the publication of this toolkit.

25

State

Interlocks Mandatory

Permissive or Both

Administrative

Judicial or Hybrid

DWI Offenders

Eligible

Indigent

Fund Y/N

Interlocks In

Use, 2012*

DWI Arrests

2011**

Interlock Manufacturers

Approved to

Provide Services State Contact

Alabama Mandatory Hybrid First offenders with

a BAC of .15 g/dL or

higher, a minor in

the vehicle, or who

caused injury to

another, upon license

reinstatement.

Y 0 287 Draeger, SmartStart AL Dept. of Public Safety

334.353.8216; AL Dept. of

Forensic Sciences (device

specifications)

334.84.4648

Alaska Mandatory Judicial Mandatory for all

offenders

N 2,175 4,420 Draeger, SmartStart Deputy Commissioner,

AK Dept. of Corrections

907.465.4670

Arizona Both Hybrid Mandatory for

all offenders

(administrative)

Permissive (courts)

N 19,153 35,496 Alcohol Detection

Systems, Consumer

Safety Technology,

Draeger, Guardian,

LifeSafer, SmartStart

Criminal Justice Liaison

Ignition Interlock

Program Manager, Motor

Vehicle Division, AZ DOT

602.712.7677

Arkansas Permissive Administrative First or subsequent

convictions

N 5,000 7,758 Consumer Safety

Technology, Draeger,

Guardian, LifeSafer,

SmartStart

Manager, Driver Control,

Office of Driver Services,

AR Dept. of Finance

and Administration

501.682.7060

California Both Hybrid Permissive for first

offenders, mandatory

for repeat offenders

N 21,900 104,345 Alco Alert Interlock,

Alcohol Detection

Systems, Autosense

International, Consumer

Safety Technology,

Draeger, Guardian,

LifeSafer, SmartStart

Manager, CA DMV Driver

Licensing Policy Unit

916.657.6217

Colorado Mandatory Administrative Mandatory for repeat

offenders; others

permissive

Y 19,363 27,314 Alcohol Sensors

International, AutoSense

International, Combined

Systems Technology,

Draeger, Guardian,

LifeSafer, SmartStart

Operations Director /

Driver Control, DO

Dept. of Revenue

303.205.5795

Connecticut Mandatory Hybrid Repeat offenders Y 1,434 8,487 Alcohol Detection

Systems, Consumer

Safety Technology,

Draeger, SmartStart

Division Chief 1 DMV 60

State Street Wethersfield,

CT 06161

860.263.5720

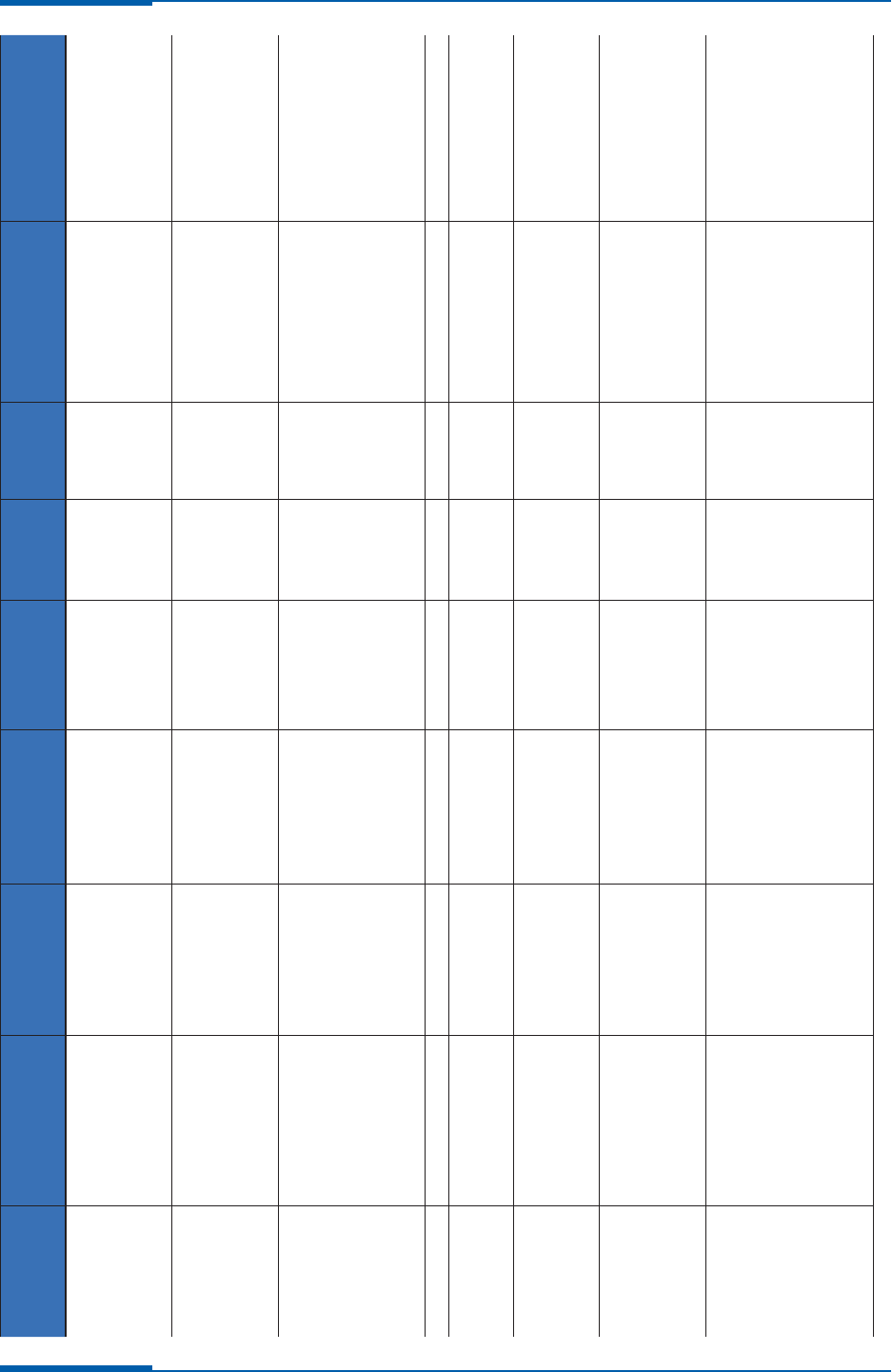

26

State

Interlocks Mandatory

Permissive or Both

Administrative

Judicial or Hybrid

DWI Offenders

Eligible

Indigent

Fund Y/N

Interlocks In

Use, 2012*

DWI Arrests

2011**

Interlock Manufacturers

Approved to

Provide Services State Contact

Delaware Mandatory Hybrid Mandatory for repeat

offenders; others

permissive

Y 232 242 Draeger, LifeSaver DE DMV P.O. Box

698 Dover, DE 19903

302.774.2408

District of

Columbia

Permissive Administrative Repeat offenders may

apply

N 43 Alcohol Detection

Systems

Florida Mandatory Hybrid Mandatory for repeat

offenders; permissive

for offenders

applying for license

reinstatement

N 9,110 43,784 Alcohol Countermeasure

Systems, LifeSafer

Bureau of Driver

Education & DUI Programs

Division of Driver Licenses

850.617.3815

Georgia Mandatory Judicial Mandatory for repeat

offenders; others

permissive.

N 2,294 31,176 Alcohol Detection

Systems, AutoSense

International, Consumer

Safety Technology,

Determinator, Draeger,

Guardian, LifeSafer,

Safety Interlock Systems,

SmartStart

Regulatory Compliance

Division GA

Dept. of Driver Services

770.413.8413

Hawaii Mandatory Judicial Mandatory for all

convictions

Y 1,254 SmartStart Highway Safety Specialist

HI DOT 808.587.6315

Idaho Permissive Judicial May be required after