i

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

Lauren Bauer, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Jay Shambaugh

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS | OCTOBER 2018

Work Requirements and Safety Net Programs

ii

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise

of opportunity, prosperity, and growth.

We believe that today’s increasingly competitive global economy

demands public policy ideas commensurate with the challenges

of the 21

st

Century. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a

judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by fostering

economic growth and broad participation in that growth, by

enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role

for effective government in making needed public investments.

Our strategy calls for combining public investment, a secure social

safety net, and fiscal discipline. In that framework, the Project

puts forward innovative proposals from leading economic thinkers

— based on credible evidence and experience, not ideology or

doctrine — to introduce new and effective policy options into the

national debate.

The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s

first Treasury Secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern

American economy. Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy,

believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would

drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent

aids and encouragements on the part of government” are

necessary to enhance and guide market forces. The guiding

principles of the Project remain consistent with these views.

MISSION STATEMENT

We thank reviewers John Coglianese, Jason Furman, Heather

Hahn, Kriston McIntosh, Ryan Nunn, and the Center on Budget

and Policy Priorities. We also thank the following who provided

research assistance: Patrick Liu, Jimmy O’Donnell, Jana Parsons,

Becca Portman, and Areeb Siddiqui.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

1

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

Work Requirements and Safety Net Programs

Lauren Bauer

The Hamilton Project and the Brookings Institution

Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach

The Hamilton Project, the Brookings Institution, and Northwestern University

Jay Shambaugh

The Hamilton Project, the Brookings Institution, and The George Washington University

OCTOBER 2018

2

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

receive disability income, people with young dependents, or

students; but, accurately exempting all those who are eligible

can be challenging and is likely to result in terminating

coverage for many people with health conditions or caregiving

responsibilities that fall outside of states’ narrow denitions.

Proponents of work requirements would ideally only like

to sanction individuals who are able to work, but choose

not to. But in practice strict enforcement of proposed work

requirements will sanction many groups, including: those

who are unable to work, those who are able to work but who

do not nd work, those who are working but not consistently

above an hourly threshold, and those who are meeting

work or exemption requirements but fail to provide proper

documentation. Evidence suggests that the vast majority of

those exposed to proposed work requirements for SNAP and

Medicaid fall into these groups.

In this paper, we analyze those who would be impacted by an

expansion of work requirements in SNAP and an introduction

of work requirements into Medicaid. Our principal

contribution is to characterize the types of individuals

who would face work requirements, describe what their

work experiences are over a two-year period, and identify

the reasons why they are not working if they experience a

period of unemployment or labor force nonparticipation. We

nd that most of those who fail the new work requirements

are either those who are in the labor force already but who

experience unstable employment, or those who might be

eligible for hardship exemptions, such as those with health

problems who are not already receiving disability income.

e compositional and labor market analyses reported below

suggest that the proposed work requirements will put at risk

access to food assistance and health care for millions who are

working, trying to work, or face barriers to working.

Introduction

Basic assistance programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp

Program) and Medicaid ensure families have access to food

and medical care when they are low-income. ese programs

li millions out of poverty while reducing food insecurity and

increasing access to medical care. ey also support work,

and increase health and economic security among families in

the short term as well as economic self-suciency in the long

term.

Today, some policymakers at the federal and state levels intend

to add new work requirements in order for beneciaries to

receive SNAP benets and participate in the Medicaid health

insurance program. In general, those exposed to a work

requirement would be required to prove that they are working

or participating in a training program for at least 20 hours per

week each month. Failure to prove that they have met the work

requirement or are eligible for an exemption would mean that

a program participant would lose food assistance benets or

health insurance for a time, or until they met the standard.

Work requirements are meant to force work-ready individuals

to increase their work eort and maintain that work eort

every month by threatening to withhold and subsequently

withholding food assistance or health coverage if a person

is not working a set number of hours. e strategy presumes

that the reasons that many low-income individuals are not

working or meeting an hourly threshold every month is

either due to their own lack of eort or to work disincentives

theoretically inherent to means-tested programs. It is clear

that some people face barriers to working outside the home

and as such, many work requirements exempt people that

Abstract

Basic assistance programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp Program) and

Medicaid ensure families have access to food and medical care when they are low-income. Some policymakers at the federal and

state levels intend to add new work requirements to SNAP and Medicaid. In this paper, we analyze those who would be impacted

by an expansion of work requirements in SNAP and an introduction of work requirements into Medicaid. We characterize the

types of individuals who would face work requirements, describe their labor force experience over 24 consecutive months, and

identify the reasons why they are not working if they experience a period of unemployment or labor force nonparticipation.

We nd that the majority of SNAP and Medicaid participants who would be exposed to work requirements are attached to the

labor force, but that a substantial share would fail to consistently meet a 20 hours per week–threshold. Among persistent labor

force nonparticipants, health issues are the predominant reason given for not working. ere may be some subset of SNAP

and Medicaid participants who could work, are not working, and might work if they were threatened with the loss of benets.

is paper adds evidence to a growing body of research that shows that this group is very small relative to those who would be

sanctioned under the proposed policies who are already working or are legitimately unable to work.

3

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

limits or work requirements for a set of individuals as a

condition for program eligibility.

Such work requirements can undermine the insurance value

of the programs, though, if people who are not working either

cannot work due to individual limitations or are unable to

nd steady work due to economic uctuations. Evaluating

whether work requirements are an appropriate policy lever—

as opposed to addressing work disincentives through other

means—thus depends on the goals of the program overall,

the characteristics of the target population, the design of the

work requirements, the cost of administering the program,

the likelihood of erroneously limiting access, and the strength

of the incentive eects.

Work requirement policies oen have diculty distinguishing

between those who are able to work and those who are unable

to work, because both groups can be hard to observe and

verify. As a result, strict enforcement of work requirements

will sanction those who are unable to work, as well as those

who could work but do not obtain employment in response to

the requirements. ey may also sanction some who are able

to work but who are not able to nd work, as well as those who

are working but fail to provide proper documentation.

In order to evaluate whether a work requirement is in

keeping with the purpose of a means-tested program, there

are a number of dimensions by which a proposal should be

evaluated. One would want to exempt those whom society

does not feel should be forced to work, accommodate changes

in the business cycle that make work more dicult to nd,

and have a system of verication and exemption that does not

raise barriers to entry or remove program participants who

should maintain access. But, one would have to ensure that

work requirements do not punish those who cannot obtain a

job due to economic conditions in their area, penalize those

who are actually working but have temporarily lost hours,

limit access to programs for an extended period of time aer

failing a work requirement, or, compromise the insurance

goals of the program in question. ese parameters can be

quite dicult to meet and they set the criterion by which

policymakers can determine whether work requirements are

inappropriate for the program in question.

ere is an extensive literature on whether work requirements

can in fact push people into the labor force, principally

studying the impacts of the 1996 Temporary Assistance for

Needy Families (TANF) reform (see Blank 2002 and Ziliak

2016 for reviews). e labor supply of the TANF population

did in fact rise, but this took place amidst a strong economy

and support from the Earned Income Tax Credt (EITC)

expansion as well (Schanzenbach 2018). For example, Fang

and Keane (2004) nd that while work requirements were the

most important factor driving the decline in participation in

welfare programs, the EITC expansion and macroeconomic

Adding explicit work requirements to assistance programs

must be analyzed in the context of program goals and from

many angles. Who would be impacted by an expansion of

work requirements? What are the administrative costs and

challenges of managing the work requirements? How do the

requirements interact with the realities of the low-wage work

experience? And how would the requirements impact the

health and economic benets to program participation? For

example, removing Medicaid coverage may have little positive

work-incentive eect for the currently healthy but may

undermine public health goals and reduce the labor supply of

those who do encounter health problems and have lost their

coverage. Removing SNAP benets from working-age adults

may impact resources available not just to them, but also to

any seniors and dependents in the household. Finally, tight

work requirements can undermine the automatic stabilizer

aspect of these programs. Instead of SNAP expanding as the

unemployment rate rises, the work requirements would cause

the program to contract, resulting in more people losing

benets when work becomes dicult for them to nd.

ere may be some subset of individuals who could work, are

not working, and might work if they were threatened with the

loss of benets. is paper adds evidence to a growing body

of research that shows that this group is very small relative to

those who would be sanctioned under the proposed policies

who are already working or are legitimately unable to work

(Bauer and Schanzenbach 2018a, 2018b; Gareld et al. 2018;

Goldman et al. 2018).

e goals of safety net programs are to provide insurance

protection to those who are experiencing poor economic

outcomes and to support those who are trying to improve

their situation. Our analysis suggests that work requirements

will harm more individuals and families than they would help

the small share who might increase their labor supply.

SNAP, Medicaid, and Incentives to

Work

e social safety net is intended to provide insurance against

bad outcomes. But, for means-tested benet programs,

economic theory suggests it may reduce the incentive to

work because (1) individuals are only eligible for a program

when their income remains below a given threshold and

(2) participants stand to lose benets as income increases

or reaches the eligibility threshold. In addition, any time

someone receives unearned income of sucient size, it may

theoretically reduce the amount of work that an individual

wants to supply to the market. In some cases, worries about

work disincentives have led to the implementation of time

4

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

factors were more important in driving the increase in work

participation (they nd work requirements had a positive

impact as well, but the contribution was smaller). Work

requirements oen come with a variety of supports and involve

dierent enforcement mechanisms and levels of stringency.

See Hamilton et al. (2001) for a detailed review as part of the

National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies. Many of

the work requirement programs that have generated positive

results also had substantial education and skills training

components (Pavetti and Schott 2016). Other studies, such

as Meyer and Rosenbaum (2001) and Grogger (2004) suggest

a smaller or negligible role for the TANF reforms compared

with other factors, especially the EITC expansion.

In this analysis, we focus more on the people who would be

impacted by new work requirements and the reasons why

they are not working, as opposed to the question of the

labor supply response. Given the extent to which the labor

market conditions—in particular for potentially impacted

populations—are dierent than those in the 1990s (Black,

Schanzenbach, Breitwieser 2017; Butcher and Schanzenbach

2018), it is helpful to consider specically what types of

individuals would be aected by proposed work requirements

and why they are not currently working to better understand

the possible impacts of expanded work requirements. In

this section we describe the SNAP and Medicaid programs,

the structure of their work incentives, and evidence of the

programs’ incentive eects on labor supply.

SNAP

Since the 1960s SNAP has provided resources to purchase

food for millions of low-income households. e goal of the

program is to provide beneciaries with resources to raise

their food purchasing power and, as a result, improve their

health and nutrition. Households are eligible for SNAP if

they meet an asset and income threshold, or if they receive

assistance from programs like Supplemental Security Income.

SNAP benet levels are targeted based on a given household’s

income and expenses.

SNAP currently addresses work disincentives in a variety of

ways. Similar to the EITC, SNAP addresses work disincentives

through an earnings disregard of 20 percent and a gradual

benet reduction schedule. is means that the size of the

earnings disregard increases as income increases and that

those with earned income receive larger SNAP benets than

those with no earned income (Wolkomir and Cai 2018).

When a person moves from being a labor force nonparticipant

to working while on SNAP, total household resources will

increase; as a beneciary’s earnings approach the eligibility

threshold, total household resources continue to increase.

e combination of the earnings disregard and a gradual

phase-out schedule—that states have the option to further

extend and smooth—ameliorate but do not eliminate work

disincentives.

States have had the option to impose work requirements on

certain beneciaries since the 1980s. Most SNAP participants

between the ages of 18 and 59 without dependents under 6

are required to register for work, accept a job if one is oered

to them, and not reduce their work eort. States are required

to operate an employment and training program, and

may require some SNAP recipients to participate or suer

sanctions. See Rosenbaum (2013) and Bolen et al. (2018) for

a detailed description of SNAP work requirements. Aer

1996, SNAP work requirements and benet time limits were

imposed on individuals aged 18–49 without dependents under

the age of 18, requiring them to register for work and accept

a job if one is oered to them. If they work or participate in

a training program for at least 20 hours per week, they can

maintain access to the program. is population is allowed

to receive 3 months of benets out of 36 months if they do

not work or participate in a training program. States are

permitted to exempt a share of individuals and apply to

the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for a waiver to

the time limit provisions, an essential capacity for SNAP’s

function as an automatic stabilizer. Studies show that when

SNAP payments increase to a local area in response to an

economic downturn, they serve as an eective scal stimulus

to the local area (Blinder and Zandi 2015; Keith-Jennings

and Rosenbaum 2015). Among other changes, the proposed

work requirements would make these regional waivers more

dicult to obtain.

SNAP improves health and economic outcomes in both the

near and long terms (see Hoynes and Schanzenbach 2016

for a review), but had a negative eect on employment in

the past. During the Food Stamp Program’s introduction in

the 1960s and 1970s, reductions in employment and hours

worked were observed, particularly among female-headed

households (Hoynes and Schanzenbach 2012). Whether work

requirements could oset this disincentive would depend on

their targeting and whether those who are not working could

readily increase their labor supply.

MEDICAID

Since 1965, the Medicaid program has been administered in

partnership between federal and state governments to provide

medical assistance to eligible individuals. e core goal of the

program is to provide health services and to cover health-care

costs in order to improve health. Under the Patient Protection

and Aordable Care Act (ACA), the eligible population

expanded to include low-income adults under the age of 65

who previously did not qualify.

Although some SNAP beneciaries have been subject to work

requirements since the 1980s, Medicaid work requirements

are being rolled out for the rst time in certain states. e ACA

does not allow work requirements to be imposed as a condition

for program participation in Medicaid, but states may apply

5

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

for a waiver under Section 1115 of the Social Security Act to

introduce work requirements if the Department of Health

and Human Services determines doing so advances program

objectives. ough the Obama administration and the U.S.

District Court for the District of Columbia (which rejected

Kentucky’s proposal for work requirements in Medicaid)

did not view work requirements as supporting core program

goals, the Trump administration has expressed its conviction

that work requirements are allowable (Centers for Medicare

& Medicaid Services 2018; Gareld, Rudowitz, and Damico

2018; Stewart v. Azar).

In the case of Medicaid, there are societal costs to taking

health insurance away from an otherwise eligible person

due to work requirements. For example, since there are

rules requiring hospitals to provide medical care to those

experiencing life-threatening emergencies regardless of the

individual’s ability to pay, those without insurance will in

many cases seek and receive treatment in ways that are more

BOX 1.

Trends in Prime-Age Labor Force Participation

For a number of decades labor force participation in the United States rose. is was especially true for prime-age (25–54) workers,

whose participation rose from 65 percent in the middle of the 20

th

century to a peak of 84 percent in 1999. is persistent trend

obscured an osetting force: Prime-age men were steadily working less while prime-age women were working more. In 1949 97

percent of prime-age men were in the labor force, but only 36 percent of women were. By 1999 those gures were 92 percent for men

and 77 percent for women.

Although women’s labor force participation rose in the 1980s and early 1990s, policymakers were concerned about the low labor

force participation for single women with children, which remained relatively at over that period. But for the past 20 years single

women who head households with children have participated in the labor market at nearly the same rate as single women without

children or married women without children. In fact, for the rst time, in 2017 the labor force participation rate of single women

with children was higher (79.09 percent) than single women without dependents (79.06 percent.) Married women with children are

still more likely to be out of the labor force (box gure 1). More recently, overall labor force participation has declined, in part due

to the aging population. Older working-age Americans (55–64) are less likely to work, with a labor force participation rate in 2017

around 72 percent for those aged 55–59 and 57 percent for those aged 60–64, compared to the current 82 percent for those aged

25–54.

ese trends provide context for who is not currently working that society might prefer to work. Most prime-age men work, though

nearly 10 percent do not. Most unmarried prime-age women with children also work. A much smaller share of older Americans

work.

BOX FIGURE 1.

Prime-Age Women’s Labor Force Participation, by Marital Status and Presence of

Children under Age 18

Married with children

Married, no children

Single with children

Single, no children

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002 2007 2012 2017

Labor force participation rate

Source: Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) (Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS] 1977–2017); authors’ calculations.

6

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

expensive for society (Institute of Medicine 2003). Second,

care delivered via insurance may include preventive care,

check-ups, and other care that is more ecient than delaying

care until a medical problem becomes severe enough to be

treated in an emergency room. us, denying insurance may

not reduce costs for society. Finally, evidence suggests that

health insurance is valued by participants at less than its cost,

making proposed work requirements less eective at raising

employment (Finkelstein, Hendren, and Luttmer 2015).

Evidence of the eect of Medicaid participation on

employment for childless adults is decidedly mixed, with

population dierences and prevailing economic conditions

as potential explanations for why studies have shown positive,

negative, and no eects on employment (Buchmueller, Ham,

and Shore-Sheppard 2016). Nevertheless, in the years since

Medicaid expansion through the ACA, the preponderance

of evidence suggests that Medicaid receipt has had little or

positive eects on labor supply (Baicker et al. 2014; Duggan,

Goda, and Jackson 2017; Garthwaite, Gross, and Notowidigdo

2014; Gooptu et al. 2016; Kaestner et al. 2017), with notable

exceptions (e.g., Dague, DeLeire, and Leininger 2017).

While there is no research evidence regarding the eect

of work requirements in Medicaid, last month, as the rst

state to implement a plan, Arkansas disenrolled program

participants for failing to comply with work requirements.

Arkansas terminated coverage for 4,353 citizens for failing

to qualify for an exemption or to meet work requirements,

while an additional 1,218 reported 20 hours per week of work

activities and 2,247 reported an exemption in the month of

August (Rudowitz and Musumeci 2018).

For these programs to accomplish their goals, eligible people

should not be dissuaded from applying for or improperly

prevented from receiving those benets. Evidence suggests

that, under a variety of scenarios, the vast majority of those

losing access to Medicaid would not lose access because they

failed to meet a work requirement, but because they failed to

successfully report their work/training activity or exemption

(Gareld, Rudowitz, and Musumeci 2018; Goldman et al.

2018). For example, in Arkansas, the only state currently

implementing a work requirement in Medicaid, beneciaries

are required to report through an online portal, Access

Arkansas (Arkansas Department of Human Services n.d.),

despite a large number of program-eligible Arkansans who

lack internet access (Gangopadhyaya et al. 2018).

Characteristics of Those Who

Would Face New Work

Requirements

Potential loss of access to SNAP and Medicaid on the basis

of a work requirement is a function of whether the person is

qualied for and veried as exempt from working and, if not,

whether the person works sucient hours each month to meet

the requirement. ose who have a categorical exemption

from work requirements—students, for example—are not

required to work unless their status changes. Exemptions

from work requirements can be applied individually for a

variety of reasons, including temporary health problems, or,

more broadly, when the unemployment rate for a location

BOX 2.

Proposed Expansion of Work Requirements

In April 2018 President Trump issued an executive order requiring that all means-tested programs be reviewed for the presence

of current work requirements, the current state of enforcement and exemption, and, for those programs without current work

requirements, whether such requirements could be added (White House 2018).

is executive order builds on executive action to implement work requirements in Medicaid for the rst time. In letters to governors

(Price and Verma 2017) and state Medicaid directors (Neale 2018), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

has oered guidance for states considering submitting a waiver request to apply work requirements for those receiving Medicaid.

Since the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services oered guidance to the states with regard to Medicaid in 2017, 14 states have

submitted work requirement proposals to HHS. HHS has approved four states’ plans, though Kentucky’s plan was vacated. e

state of Arkansas has begun to enforce work requirements (Urban Institute 2018). State proposals vary in terms of the age range and

household composition of exposure, who is exempt, and the hours required for work or approved activities.

Additionally, in reauthorizing the Farm Bill, in June 2018 the House voted to expand the scope of who is required to work in order

to receive SNAP benets to include adults 18–59 with dependent children aged 6–18 as well as those aged 50–59 without dependents

under the age of 6. As of publication, the conference committee is considering this proposal.

7

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

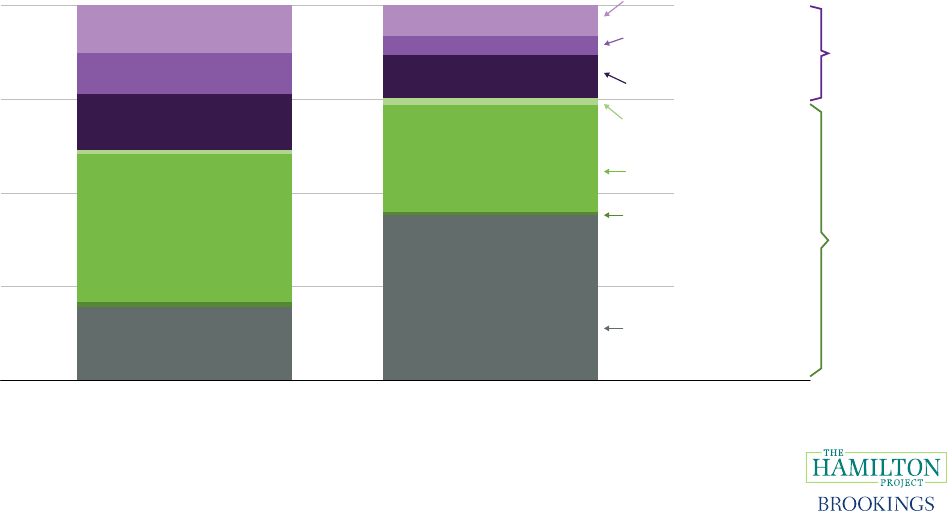

FIGURE 1.

Exposure to Work Requirements among Adult SNAP Participants, 2017

Source: ASEC (BLS 2018); authors’ calculations.

is high. Certain educational or training activities can also

qualify for meeting hourly thresholds.

To highlight one diculty in designing a work requirement

policy, consider the group of SNAP and Medicaid participants

who usually are not working. Many individuals in this group

are not expected to work, including the elderly, disabled,

children, students, caregivers, and the inrm. In fact, nearly

two thirds of individuals who participate in SNAP are elderly,

disabled, or children (USDA 2017a).

Some of these characteristics are straightforward to observe

and verify, such as age, school enrollment, and receipt of

disability benets. Other characteristics are dicult to

observe and costly to verify, such as those with temporary

medical conditions that make it impossible for them to work,

those who have a chronic health condition but do not meet the

high standard set for disability benets (or have not applied

for disability benets), and those who do not have the skills,

childcare, or transportation to obtain a job in their local

economy at present. Another share of this group might be

capable of employment but not willing to work; in that case

the work requirements might or might not provide enough

incentive for them to get jobs.

Using data from the Current Population Survey Annual Social

and Economic Supplement (ASEC), we quantify exposure

to work requirements in 2017 based on broad demographic

characteristics. To do so, we separate those who would likely

qualify for a categorical exemption from those who would

be required to work or who would qualify for a waiver to

maintain eligibility. To be clear, while we model who is

eligible for a categorical exemption, evidence suggests that not

everyone in these groups will successfully navigate the system

and obtain the exemption; in fact, estimates suggest that most

people who lose coverage under this policy will be eligible for

an exemption or already be working. For SNAP we followed

the federal guidelines for categorical exemption; for Medicaid

we created a composite from among the dierent plans put

forth by the states based on how frequently such groups are

exempt.

For SNAP, minors, those who are older than 59 years, students,

those receiving disability benets, and those with a child

under the age of 6 are exempt from both current and new,

proposed work requirements. e samples are further limited

to U.S. citizens and nonactive military. For simplication,

we describe those aged 18-49 without dependents as being

currently exposed to work requirements and those aged 18–

59 with a dependent between the ages of 6 and 17 (inclusive)

as well as those between the ages of 50 and 59 with no

dependents under the age of 6 as newly required to meet

work requirements or to participate in a training program in

order to receive SNAP benets. For the current group, some

Age 18−49,

no dependents

11.5%

More than 59 years old

24.0%

Dependent

less than 6 years old

23.6%

Disability income

13.6%

Students

5.7%

Age 18−49,

dependent age 6–17

13.1%

Age 50−59,

no dependents

less than 6 years old

8.5%

Current

Exempt New

8

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

may live in places exempt from work requirements or have an

unobserved good-cause exemption.

How many adult SNAP participants are—or would be—

exposed to work requirements? Figure 1 shows the entire adult

population (18 or older) who reported SNAP participation in

2017. Each rectangle represents a share of the total population

and whether the individuals in that share were eligible for a

categorical exemption to work requirements (teal), were in a

population currently exposed to a work requirement (green),

or would be newly exposed to work requirements under

the House proposal (purple). e shaded rectangles sum to

100percent, the total adult SNAP participant population.

Under the House bill parameters (described in box 2),

combined with current work requirements, one third of all

adults who reported receiving SNAP benets during 2017

would be exposed to work requirements, though a portion of

those impacted could apply for exemptions based on veried

health- or work-related concerns. Some already face work

requirements, but 22 percent of all participants would be

newly exposed to work requirements under the House bill

(purple).

Figure 1 also shows the reasons some participants would be

exempt from new requirements. e majority (67 percent)

of adults currently receiving SNAP benets would still be

exempt from work requirements based on age, having a

dependent under the age of 6, or having student or disability

status. Some would be exempt for multiple reasons; we group

them rst by age, then by the presence of dependents, and

then by student or disability status. For example, while gure

1 shows just 14percent exempt due to disability, 24percent of

all adult SNAP recipients report receipt of disability benets.

In 2017, 2.2million people who reported SNAP benet receipt

were exposed to work requirements during the year based on

their demographic characteristics. Under the House proposal

and based on 2017 numbers, this would more than double

with 2.5million adults aged 18–49 with dependent children

aged 6–17 and 1.6million adults aged 50–59 who would be

exposed to work requirements nationally for the rst time.

In any household, there may be others who rely on the benets,

and not just the individual facing work requirements. e

solution to concerns for other individuals in the household

has typically been to waive work requirements for those

who likely cannot work or who reside with those for whom

shielding from benet loss is a priority. Any reduction in

SNAP benets to adults would reduce the total amount of

resources available to them to purchase food, including food

for children. ere are 3.5 million children and 710,000

FIGURE 2.

Exposure to Work Requirements among Adult Medicaid Participants, 2017

Source: ASEC (BLS 2018); authors’ calculations.

More than 64 years old

or Medicare

11.9%

Dependent

less than 6 years old

22.1%

Disability

income

12.9%

Students

6.3%

Age 18−49,

no dependents less than 6 years old

30.9%

Age 50−64,

no dependents

less than 6 years old

15.8%

Exempt

New

9

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

seniors in these households that would be exposed to possible

benet loss due to work requirements.

We perform the same exercise to show the share of Medicaid

beneciaries who are targeted by the policy based on potential

new rules (gure 2). Minors, seniors (those over the age of

64), students, those receiving disability benets or Medicare,

and those with a child under the age of 6 are those who are

generally eligible to be exempt from work requirements based

on the plans that states submitted, though there is variation

across states. We apply these categories to the entire adult

Medicaid population, acknowledging that not every state has

submitted a work requirement proposal and that the aected

population varies by state plans. A nationwide expansion of

these rules would target 22.4million Americans for a possible

loss of Medicaid coverage.

Almost half of all adult Medicaid beneciaries would be

targeted by work requirements if the composite rules were

applied nationwide. e largest share of those exempt

from work requirements are parents with young children

(22 percent) followed by those reporting disability income

(13 percent) and Medicare/Medicaid dual enrollees

(12 percent). About 6 percent of Medicaid participants are

students.

Volatility in the Low-Wage Labor

Market

e decline in labor force participation—especially among

prime-age males—has drawn extensive attention in academic

and policy circles (e.g., Abraham and Kearney 2018; Council

of Economic Advisers [CEA] 2016; Juhn 1992). Some recent

academic work has emphasized the fact that participation may

be declining in part because an increasing number of labor

force participants cycle in and out of the labor force: a pattern

with direct relevance to proposed work requirements. e

most comprehensive look at the behavior of people cycling

through the labor force is Coglianese (2018). He documents

that, among men, this group—which he refers to as “in-and-

outs”—takes short breaks between jobs, returns to the labor

force fairly quickly (within six months), and, crucially, is no

more likely than a typical worker to take another break out of

the labor force. See also Joint Economic Committee (2018) for

a discussion of the in-and-out behavior of nonworking prime-

age men and reasons for their nonemployment.

SNAP or Medicaid participants who are employed but who

work in jobs with volatile employment and hours would be at

risk of failing work requirements. is group includes those

who lose their job; for example, the House bill sanctions

participants for months they are not working or in training for

at least 20 hours per week, even if they were recently employed

and are searching for a new job. Similarly, those who work in

jobs with volatile hours would be sanctioned in the months

that their average hours fell below 20 hours per week, whether

due to illness, lack of hours oered by the employer, or too few

hours worked by the participant if they fail to receive a good-

cause waiver.

Low-wage workers in seasonal industries such as tourism

would potentially be eligible for SNAP in the months when

they are working, but not in the months without employment

opportunities. In other words, while benets are most

needed when an individual cannot nd adequate work,

under proposed work requirements these are the times that

benets would be unavailable. Disenrollment could make

it more dicult for an individual to return to work—for

example, if a person with chronic health conditions is unable

to access needed care while they are between jobs. Any work

requirement that banned individuals from participation for

a considerable amount of time aer failing the requirements

would be even more problematic for those facing churn in the

labor market.

In a set of analyses, Bauer and Schanzenbach (2018a, 2018b)

found that although many SNAP beneciaries work on

average more than 20 hours a week every month, they

frequently switch between working more than 20 hours and

a dierent employment status over a longer time horizon.

Using the ASEC, those authors found that, over the course

of 16 months between 2016 and 2018, about 20 percent of

individuals aged 18–59 without a dependent child under age

6 switched between working more than 20 hours a week and

working fewer than 20 hours per week, seeking employment,

or being out of the labor force.

In this economic analysis we examine labor force status

transitions and the reasons given for not working among those

targeted for work requirements over 24 consecutive months,

January 2013–December 2014, using the rst two waves of the

Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

1

By using

a dataset that allows us to track workers over time, we identify

the share of program participants who are consistently out

of the labor force, the share who would consistently meet

a work requirement, and the share who would be at risk of

losing benets based on failing to meet a work requirement

threshold.

We assume that to comply with a program’s work requirement,

beneciaries would have to prove each month that they are

working for at least 20 hours per week averaged over the

month, which is the typical minimum weekly requirement

among the SNAP and Medicaid work requirement proposals.

Looking rst at SNAP and then at Medicaid, we calculate

the share of program participants who would be exposed

to benet loss because they are not working sucient hours

10

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

over the course of 24 consecutive months. Among those who

would be exposed to benet loss and who experienced a gap in

employment, we describe the reasons given for not working to

help quantify potential waiver eligibility.

We remove from the analysis all those who have a categorical

exemption. For SNAP and Medicaid, we exclude those outside

the targeted age range, those with children under 6, full- or

part-time students, and those reporting disability income.

ose receiving Medicare are additionally excluded from the

Medicaid analysis. As an instructive example, the labeled

group “18–49, no dependents” is additionally exclusive of

students and those reporting disability income. Program

participants are those who reported receiving SNAP or

Medicaid at any point between January 1, 2013, and December

31, 2014.

We categorize each individual in each month into one of

four categories: (1) employed and worked more than 20

hours a week on average, (2) employed and worked less than

20 hours a week on average, (3) unemployed and seeking

employment, or (4) not in the labor force. If a worker was

employed at variable weekly hours but maintained hours

above the monthly threshold (80 hours for a four-week month

and 120 hours for a ve-week month), then we categorize

them as “employed and worked more than 20 hours a week

for that month.” Individuals are considered to have a stable

employment status if they do not change categories over two

years, and are considered to have made an employment status

transition if they switched between any of these categories at

least once. ere is no employment status transition when a

worker changes jobs but works more than 20 hours a week at

each job.

EXPOSURE TO PROPOSED WORK REQUIREMENTS IN

SNAP

Among working-age adults, SNAP and Medicaid serve a

mix of the unemployed, low-income workers, and those who

are not in the labor force (USDA 2017b). Figure 3 describes

employment status by those groups who are currently exposed

to work requirements and who would be newly subject to work

requirements under the House proposal.

During the Great Recession, waivers to work requirements

were implemented nationwide. During the time period

covered by the SIPP (2013–14), 8 states stopped implementing

these waivers fully, and 10 states partially (Silberman

2013).

2

For analytic purposes, we look at employment status

transitions among 18 to 49 year-olds without dependents as the

demographic group currently exposed to work requirements,

regardless of whether they lived in state in which waivers

were implemented during 2013 and 2014. ose receiving

SNAP benets who are in the demographic group currently

exposed to work requirements—adults aged 18–49 with no

dependents—generally participate in the labor market, with

just 25percent consistently not in the labor force (discussed

FIGURE 3.

Employment Status over Two Years, SNAP Participants

Source: Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) (U.S. Census Bureau 2013–14); authors’ calculations.

0

25

50

75

100

Age 18−49,

no dependents

Age 18−49,

dependent 6−17

Age 50−59,

no dependent under 6

Percent

Stable

Transitioned

Employed <20 hours

Between 20+ hours

and unemployment

or not in the labor force

Between 20+ hours

and <20 hours

Employed 20+ hours

Unemployed

Not in labor force

Other transition

Currently

exposed

Newly

exposed

11

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

below). While 58percent worked at least 20 hours per week

in at least one month over two years, 25percent were over the

threshold at some point but fell below the 20-hour threshold

during at least one month over two years. Very few are always

working less than 20 hours a week or always unemployed (less

than 2 percent in either case), and 14 percent move across

these categories.

ose aged 18–49 who are not subject to the three-month

time limit because they have a dependent aged 6–17 but

who would face it under the House proposal demonstrate a

similar distribution of employment status as those without a

dependent, but they are more likely to work. ere are fewer

individuals who are always out of the labor force (14percent)

and more that consistently work 20 hours a week or more

(46 percent).

3

ere is also substantial month-to-month

churn (16 percent) between working above 20 hours per

week and less than 20 hours per week and churn (12percent)

between working above 20 hours per week and being either

unemployed or not in the labor force. is highlights the

number who are actively in the workforce and meeting the 20-

hour threshold in at least one month, but who might fail new

work requirements from time to time.

Older SNAP participants (aged 50–59 without dependents

under age 6) who would also be newly exposed to work

requirements and time limits have a distinct employment

status pattern from those aged 18–49. Almost half were

permanently out of the labor force in large part due to their

health. While 23 percent worked consistently above the

threshold of 20 hours a week, nearly as many (18 percent)

worked above the threshold at some point but also below the

threshold at some point, meaning they would fail the work

requirement despite having sometimes met the threshold.

ere is a meaningful portion of SNAP participants in

the labor force and working, but not all are working above

the monthly work requirement threshold consistently.

Coglianese’s (2018) nding that workers who are in and out of

the labor force are not more likely to take another break later

on suggests it is unclear how much more consistently work

requirements would attach these people to the labor force.

We next examine the reasons given for not working over the

two-year period, rst for those aged 18–49 with a dependent

between the ages of 6 and 17, and second for those 50 to 59

without a dependent under age 6 (gures 4a and 4b). e

FIGURE 4A.

Most-Frequent Reason for Not Working for Pay, SNAP Participants Aged 18–49

with Dependents Age 6–17

Source: SIPP (U.S. Census Bureau 2013–14); authors’ calculations.

Caregiving

3.8%

Health or

disability

5.1%

Other

4.7%

Student

2.5%

Work-related

34.6%

Caregiving

1.5%

Health or

Disability

7.3%

Student

2.7%

Work-

related

2.5%

Not in

Labor

Force

Labor Force Participant

Stable work, never asked

35.0%

Not interested

in working

0.3%

12

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

FIGURE 4B.

Most-Frequent Reason for Not Working for Pay, SNAP Participants Aged 50–59 with No

Dependent under Age 6

Source: SIPP (U.S. Census Bureau 2013–14); authors’ calculations.

Not in Labor Force

Labor Force Participant

Stable work, never asked

19.2%

Caregiving

1.7%

Health or

disability

13.6%

Work-related

16.5%

Health or

Disability

39.6%

Work-related

3.8%

Not interested

in working

0.7%

Early

retirement

0.7%

Student

0.2%

Other

1.8%

Caregiving

1.1%

Early retirement

0.7%

Not interested

in working

0.2%

Other

0.1%

green crosshatch shows the share of the population that

did not experience a gap in employment over the two-year

period, and thus were never asked why they were not working.

Among those who were asked why they were not working

for pay during at least one week, we report the reason for not

working in months they were not working. ose in solid

shades of green were in the labor force but experienced at least

one spell of unemployment or labor force nonparticipation.

ose in the blue were out of the labor force for the entire two-

year period. Each person is assigned one reason—their most

frequent reason—for not working.

Among those aged 18–49 with dependents aged 6–17 who are

newly exposed to work requirements (gure 4a), 86 percent

were in the labor force at some point over two years but not all

worked stably. Among those who did not work for pay for at

least one week but were in the labor force, the overwhelming

majority gave work-related reasons (68 percent), such as

temporary loss of job, temporary loss of hours (e.g., weather-

related, not getting enough shis, etc.), or a company shutting

down a plant or location. Other large groups include those

who are caregivers and those with health concerns. In a

program with extensive good-cause waivers, it appears the

bulk of these workers would not lose benets if waivers were

implemented with delity; but the administrative burden

required to sort those with work-related problems from those

who choose to not work could be quite high.

Among those out of the labor force for the entire two-year

period, more than half cite health reasons for being out of

the labor force. In total, 0.3percent of those aged 18–49 who

would be newly exposed to work requirements and who were

labor force nonparticipants said that they were not interested

in working.

Among individuals aged 50–59 (gure 4b), far more are out

of the labor force consistently and far fewer have stable work.

Overall, health (87 percent) and work-related (8 percent)

issues dominate. e prevalence of health problems is striking

considering we have already limited the sample to those not

receiving disability payments. Fewer than 1 percent were

retired or not interested in working.

e share of older SNAP participants listing caregiving as

a reason for being not in the labor force is notably smaller

than the share of the younger SNAP participant population.

13

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

Roughly 11 percent of SNAP participants aged 18–49 with

a dependent 6–17 that were out of the labor force for the

entire 24-month period list caregiving as a reason for not

being in the labor force. However, even 11 percent is smaller

than many might expect. Many caregivers who are not in

the labor force are in two-adult households where the other

adult is working. In addition, many are in households with

dependents aged 0–5, and those households are exempt from

work requirements.

In summary, based on 2013–14 data, 5.5million adult SNAP

participants would be newly exposed to work requirements

with 3.8million who would have failed them at some point

in this two-year window. Notable among those who were

asked about a spell of not working, 2.1million report health

or disability issues and 1.5million report work-related issues.

Only about 90,000 list a lack of interest or early retirement as

their reason for not working.

EXPOSURE TO PROPOSED WORK REQUIREMENTS IN

MEDICAID

We study the work participation of Medicaid beneciaries in a

similar manner. Unlike SNAP, there is no current population

of participants who face work requirements across the country

to use as a comparison group. As noted above, previous

administrations and the courts have not viewed Medicaid

work requirements as supporting core program goals; there

are substantive doubts about whether work requirements for

health insurance are appropriate. Nevertheless, we consider

the employment status of Medicaid beneciaries to illuminate

how such requirements would function.

Since Medicaid beneciaries do not currently face work

requirements, we do not separately examine the population

aged 18–49 without dependents. It is instructive to

dierentiate the work status transitions of younger (aged

18–49) and older (aged 50–64) Medicaid beneciaries,

restricted to those who either have a dependent 6–17 or no

dependents, i.e. no dependents under the age of 6. We identify

employment status transitions and the reasons given for not

working among those targeted for work requirements over 24

consecutive months (January 2013–December 2014).

Figure 5 shows that over two years (2013 and 2014), 80percent

of Medicaid beneciaries aged 18–49 without a dependent

child under age 6 were in the labor force at some point.

While about 40percent consistently worked over the 20-hour

threshold, 25 percent worked more than 20 hours at some

point but would potentially lose benets for falling below the

20-hour threshold for a month at another point.

e picture is quite dierent for older Medicaid beneciaries

(50 to 64) who would be exposed to work requirements. Of

that population, 44percent were out of the labor force for all

24 months. About 29percent worked consistently more than

20 hours a week and about 17percent worked more than 20

hours at least once but failed to do so every month. e reasons

given among working-age adult Medicaid beneciaries not

working for pay suggest that labor market reasons dominate

FIGURE 5.

Employment Status over Two Years, Medicaid Participants

SIPP (U.S. Census Bureau 2013–14); authors’ calculations.

0

25

50

75

100

Age 18−49,

no dependent under 6

Age 50−64,

no dependent under 6

Percent

Stable

Transitioned

Employed <20 hours

Between 20+ hours

and unemployment

or not in the labor force

Between 20+ hours

and <20 hours

Employed 20+ hours

Unemployed

Not in labor force

Other transition

14

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

FIGURE 6A.

Most-Frequent Reason for Not Working for Pay, Medicaid Participants Aged 18–49 with No

Dependents under Age 6

Source: SIPP (U.S. Census Bureau 2013–14); authors’ calculations.

Caregiving

4.6%

Health or

disability

7.3%

Other

4.5%

Student

3.9%

Work-related

25.1%

Health or

Disability

14.5%

Student

1.6%

Work-

related

2.0%

Not in

Labor

Force

Labor Force Participant

Stable work, never asked

33.8%

Caregiving

1.5%

Not interested

in working

1.1%

FIGURE 6B.

Most-Frequent Reason for Not Working for Pay, Medicaid Participants Aged 50–64 with No

Dependents under Age 6

Not in Labor Force

Labor Force Participant

Stable work, never asked

28.0%

Health or disability

8.8%

Work-related

12.5%

Health or Disability

35.0%

Work-related

3.7%

Early

retirement

1.9%

Other

2.3%

Caregiving

1.7%

Early retirement

3.1%

Not interested

in working

0.5%

Not interested

in working

0.9%

Care-

giving

1.4%

15

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

among labor force participants and health reasons dominate

among labor force nonparticipants (gures 6a and 6b). Once

again, only a small number of labor force nonparticipants are

not interested in work or are retired.

Among older participants of Medicaid (aged 50–64 without a

dependent under age 6, the population making up 37percent

of the sample population), 35 percent of those with Medicaid

coverage are out of the labor force for health reasons; this

group represents 79 percent of those who were not in the

labor force for the full two years. It is worth noting that

work requirements for this group would necessitate either

lax requirements with a very large portion of the population

getting waivers, or an administratively burdensome process

to determine which individual’s health concerns truly limit

them from work.

Work Status in a Snapshot vs.

Two Years

In its report on work requirements, the Council of Economic

Advisers (CEA 2018) looked at employment among adult

program participants for the month of December 2013 using

the SIPP and found that about three in ve participants

worked fewer than 20 hours per month. e CEA concludes

that this level of work—or lack thereof—“suggest[s] that

legislative changes requiring them to work and supporting

their transition into the labor market, similar to the approach

in TANF, would aect a large share of adult beneciaries and

their children in these non-cash programs” (1–2).

A critical empirical takeaway from the analysis presented

herein is that frequent movement between labor status

categories over time increases the number of people exposed

to losing benets for failing to consistently meet a work

requirement, and decreases the number of people who are

entirely out of the labor market. We now examine how the

analysis of work experiences diers when we compare a

snapshot in time—one month—with analysis that includes

transitions across status over two years. When we compare the

one month of SIPP data cited in the CEA report (December

2013) against 24 months, we nd that fewer program

participants are labor force nonparticipants and fewer meet

the work requirement threshold.

Figure 7 demonstrates how observed employment status is

dierent in one month versus two years. e rst two bars

show employment status categories for the full population

aged 18–59 without dependents aged 0–5, disability

payments, or status as students. e second two bars show

employment status categories in one month and two years

for SNAP participants aged 18–59 with no dependents aged

0–5, disability payments, or status as students. An “other”

transition during a one-month period are those who report

FIG U R E 7.

Employment Status in One Month vs. Two Years, SNAP

SIPP (U.S. Census Bureau 2013–14); authors’ calculations.

Month Two year Month Two year

0

25

50

75

100

Percent

Overall SNAP

Stable

Transitioned

Employed <20 hours

Between 20+ hours

and unemployment

or not in the labor force

Between 20+ hours

and <20 hours

Employed 20+ hours

Unemployed

Not in labor force

Other transition

16

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

FIGURE 8.

Employment Status in One Month vs. Two Years, Medicaid

SIPP (U.S. Census Bureau 2013–14); authors’ calculations.

One month Two years One month Two years

0

25

50

75

100

Percent

Stable

Transitioned

Employed <20 hours

Between 20+ hours

and unemployment

or not in the labor force

Between 20+ hours

and <20 hours

Employed 20+ hours

Unemployed

Not in labor force

Other transition

Overall Medicaid

being unemployed and a labor force nonparticipant during

dierent weeks within December 2013.

e rst feature that jumps out of the data is that far fewer

people are out of the labor force than is generally assumed.

While a one-month snapshot shows that 20 percent of the

overall population is not working (either out of the labor

force or unemployed), over the course of two years more

than 90percent of the overall population is employed at some

point. Many people are not truly on the sidelines as much as

they are cycling in and out of the game. Furthermore, fewer

people are solidly in the 20 hours plus–workforce. e share of

the overall population that stably works more than 20 hours

per week falls from 76percent in the one-month snapshot to

69percent over two years.

Looking only at those who participated in SNAP at any point

during the two-year period, the one-month snapshot is also

dierent from the two-year, both in terms of the number

of participants out of the labor force and the number who

would retain benets under the work requirement proposal.

Instead of 42percent being out of the labor force and roughly

11percent unemployed in the one-month snapshot—leading

to more than half of the group being labeled “not working”

in the one-month snapshot—roughly 29 percent are out of

the labor force and just 1percent are persistently unemployed

over two years, meaning fewer than one third are not working

consistently. Recall that the higher “not working” rate among

SNAP beneciaries is largely driven by those aged 50–59.

SNAP recipients aged 18–49 without dependents have a

“not working” rate of 25 percent over two years, and those

with dependents aged 6–17 have a “not working” rate of just

14percent. Almost a quarter of SNAP participants would fail

the work requirements some months and pass them in others,

with the majority giving work-related reasons for their change

in status.

A similar pattern holds for Medicaid beneciaries: the

monthly snapshot overstates the number of labor force

nonparticipants and understates those who would meet a

work requirement. ere is a 10 percentage point–reduction

in the share of those not working over one month (39percent)

versus two years (29percent). Forty-twopercent would meet

the work requirement in one month, but only 36percent do

over two years. In addition, in the two-year sample 22percent

of participants work over 20 hours in at least one month in the

sample but fail to in other months (gure 8).

Conclusion

e combination of a strong labor market, work requirements

to receive cash benets through TANF, and work incentives

generated by the EITC raised labor force participation rates

among single mothers in the mid-1990s (Ziliak 2016), leading

some to believe that further participation gains could be

obtained by extending only the work requirement component

to other programs (Haskins 2018; CEA 2018).

17

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

Work requirements are intended to counter any work

disincentives that come from a social safety net and to

ensure that society is not unnecessarily supporting people

who could otherwise support themselves. At the same time,

such work requirements add administrative complexity to

social programs and risk keeping benets from parts of the

population that should be receiving them. is economic

analysis establishes a set of facts that are relevant when

considering the expansion of work requirements.

What types of populations will face these new work

requirements? How many would fail to meet the requirements?

Do program participants appear to already be in the labor

force facing work-related constraints on hours or do they

choose not to work? And how many would in theory be

eligible for waivers relative to those individuals that society

would like to push toward work?

A large number of SNAP and Medicaid participants who

would face new work requirements cycle in and out of the labor

force and would thus lose benets at certain times. Among

those who are in the labor force, spells of unemployment are

either due to job-related concerns or health issues. Very few

reported that they were not working due to lack of interest.

Among those out of the labor force for the entire two-year

period, health concerns are the overriding reason for not

working, even aer removing those who receive disability

benets from the sample. e older portion of the population

newly exposed to work requirements is more likely to be out of

the labor force for extended periods of time. Among this group,

again, health reasons are the overriding factor in not working.

Work requirements for this group might push more onto

disability rolls, make the disability adjudication even more

consequential, and require a separate health investigation to

settle all the necessary waivers. Failure to receive a waiver

would result in disenrollment; losing access to these programs

would reduce resources available to purchase food and health

insurance among otherwise eligible households.

For those who qualify for exemptions, satisfy waiver

requirements, or work enough to meet the requirements, there

are still signicant informational and administrative barriers

to compliance. Program participants must understand how

the work requirement policy relates to them, obtain and

submit documentation, and do so at the frequency prescribed

by the state (Wagner and Solomon 2018). Frequent exposure to

verication processes, such as the monthly reporting periods

prescribed in the Agricultural Act of 2014 (the Farm Bill) and

many states’ Medicaid proposals, increases the administrative

burden on participants and enforcers, the likelihood of error,

and cost (Bauer and Schanzenbach 2018b). ese continuing

roadblocks to participation, with attendant informational and

transactional costs, are likely to result in lower take-up among

the eligible population and disenrollment (Finkelstein and

Notowidigdo 2018).

Looking at snapshots of work experience, such as a single

month, inates both the number of SNAP and Medicaid

participants who are out of the labor force and the number of

people who work sucient hours to satisfy work requirements.

Over 24 consecutive months the number of SNAP and

Medicaid program beneciaries not working or seeking work

as well as those working consistently above 20 hours fall

substantially.

ere are safety net levers that can be used to pull those out

of the labor force into work. Steps such as increasing the EITC

might be a very eective way to increase work participation

in this group without the same administrative burdens and

negative spillovers to vulnerable populations. (See Hoynes,

Rothstein, and Runi 2017 for a specic proposal along these

lines.) at proposal is estimated to increase participation by

600,000 people. Raising the returns to work via the EITC or

other measures, creating training or educational opportunities

that can increase individuals’ human capital, and providing

child care or improved treatment and medical care to reduce

health barriers to work could make full attachment to the

labor force more viable for many individuals.

18

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

Endnotes

1. See technical appendix tables 1 and 2 for additional work status transition

statistics.

2. e states not implementing able-bodied adult without dependents

waivers at some point during 2013–14 are: Delaware, Guam, Iowa, Kansas,

Nebraska, Oklahoma, Utah, Virginia, and Wyoming. States implementing a

partial waiver (partial referring to dierent parts of the state or only part of

the year): Colorado, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, North Dakota,

Ohio, South Dakota, Texas, Vermont, Wisconsin.

3. ose who meet the 20-hour threshold monthly hours variable include both

those who meet the threshold every week and those whose hours varied

each week but averaged to 20 hours per week each month. e volatility of

their hours may suggest they are more likely to fail the work requirement

threshold but they did not do so over the two-year window.

References

Abraham, Katharine G., and Melissa S. Kearney. 2018. “Explaining

the Decline in the U.S. Employment-to-Population Ratio:

A Review of the Evidence.” Working Paper 24333, National

Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Agricultural Act of 2014 (Farm Bill), Pub.L. 113-79 (2014).

Arkansas Department of Human Services. n.d. “Access Arkansas.”

(https://access.arkansas.gov.)

Baicker, Katherine, Amy Finkelstein, Jae Song, and Sarah Taubman.

2014. “e Impact of Medicaid on Labor Market Activity

and Program Participation: Evidence from the Oregon

Health Insurance Experiment.” American Economic Review

104 (5): 322–28.

Bauer, Lauren, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach. 2018a, July

27. “Employment Status Changes Put Millions at Risk

of Losing SNAP Benets for Years.” Blog. e Hamilton

Project, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

———. 2018b, August 9. “Who Loses SNAP Benets If Additional

Work Requirements Are Imposed? Workers.” Blog. e

Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

Black, Sandra E., Diane W. Schanzenbach, and Audrey Breitwieser.

2017. “e Recent Decline in Women’s Labor Force

Participation.” In Driving Growth through Women’s

Economic Participation edited by Diane W. Schanzenbach

and Ryan Nunn, 5–17. Washington, DC: e Hamilton

Project.

Blank, Rebecca. 2002.“Evaluating Welfare Reform in the United

States.” Journal of Economic Literature 40 (4): 1105–66.

Blinder, Alan S., and Mark Zandi. 2015. “e Financial Crisis:

Lessons for the Next One.” Policy Futures, Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities, Washington, DC.

Bolen, Ed, Lexin Cai, Stacy Dean, Brynne Keith-Jennings, Catlin

Nchako, Dottie Rosenbaum, and Elizabeth Wolkomir.

2018. “House Farm Bill Would Increase Food Insecurity

and Hardship.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,

Washington, DC.

Buchmueller, omas, John C. Ham, and Lara D. Shore-Sheppard.

2016. “e Medicaid Program.” In Economics of Means-

Tested Transfer Programs in the United States, Vol. I, edited

by Robert A. Mott, 21–136. Chicago, IL: University of

Chicago Press.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 1977–2017. “Current Population

Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement.” Bureau

of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Washington,

DC. Retrieved from IPUMS-CPS, University of Minnesota.

———. 2018. “Current Population Survey Annual Social and

Economic Supplement.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S.

Department of Labor, Washington, DC. Retrieved from

IPUMS-CPS, University of Minnesota.

Butcher, Kristin F., and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach. 2018.

“Most Workers in Low-Wage Labor Market Work

Substantial Hours, in Volatile Jobs.” Policy Futures, Center

on Budget and Policy Priorities, Washington, DC.

e Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2018. “Remarks

by Administrator Seema Verma at the 2018 Medicaid

Managed Care Summit.” As prepared for delivery:

September 27, 2018. e Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services, Washington, DC.

Coglianese, John. 2018, February. “e Rise of In-and-Outs:

Declining Labor Force Participation of Prime Age Men.”

Working Paper, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Council of Economic Advisers (CEA). 2016. “e Long-Term

Decline in Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation.”

Council of Economic Advisers, White House, Washington,

DC.

———. 2018. “Expanding Work Requirements in Non-Cash

Welfare Programs.” Council of Economic Advisers, White

House, Washington, DC.

Dague, Laura, omas DeLeire, and Lindsey Leininger. 2017. “e

Eect of Public Insurance Coverage for Childless Adults

on Labor Supply.” American Economic Journal: Economic

Policy 9 (2): 124–54.

Duggan, Mark, Gopi Shah Goda, and Emilie Jackson. 2017. “e

Eects of the Aordable Care Act on Health Insurance

Coverage and Labor Market Outcomes.” Working Paper

23607, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge,

MA.

Fang, Hanming, and Michael P. Keane. 2004. “Assessing the Impact

of Welfare Reform on Single Mothers.” Brookings Papers on

Economic Activity (1): 1-95.

19

The Hamilton Project • Brookings

Finkelstein, Amy, Nathaniel Hendren, and Erzo F. P. Luttmer. 2015.

“e Value of Medicaid: Interpreting Results from the

Oregon Health Insurance Experiment.” Working Paper

21308, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge,

MA.

Finkelstein, Amy, and Matthew J. Notowidigdo. 2018. “Take-up and

Targeting: Experimental Evidence from SNAP.” Working

Paper 24652, National Bureau of Economic Research,

Cambridge, MA.

Gangopadhyaya, Anuj, Genevieve M. Kenney, Rachel A. Burton,

and Jeremy Marks. 2018. “Medicaid Work Requirements in

Arkansas: Who Could Be Aected, and What Do We Know

about em?” Urban Institute, Washington, DC.

Gareld, Rachel, Robin Rudowitz, and Anthony Damico. 2018.

“Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid and Work.”

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, San Francisco, CA.

Gareld, Rachel, Robin Rudowitz, and MaryBeth Musumeci. 2018.

“Implications of a Medicaid Work Requirement: National

Estimates of Potential Coverage Losses.” Henry J. Kaiser

Family Foundation, San Francisco, CA.

Gareld, Rachel, Robin Rudowitz, MaryBeth Musumeci,

and Anthony Damico. 2018. “Implications of Work

Requirements in Medicaid: What Does the Data Say?”

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, San Francisco, CA.

Garthwaite, Craig, Tal Gross, and Matthew J. Notowidigdo. 2014.

“Public Health Insurance, Labor Supply, and Employment

Lock.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129 (2): 653–96.

Goldman, Anna L., Stee Woolhandler, David U. Himmelstein,

David H. Bor, and Danny McCormick. 2018. “Analysis of

Work Requirement Exemptions and Medicaid Spending.”

JAMA Internal Medicine online, September 10.

Gooptu, Angshuman, Asako S. Moriya, Kosali I. Simon, and

Benjamin D. Sommers. 2016. “Medicaid Expansion Did

Not Result in Signicant Employment Changes or Job

Reductions in 2014.” Heath Aairs 35 (1): 111–18.

Grogger, Jerey. 2004. “Welfare Transitions in the 1990s: e

Economy, Welfare Policy, and the EITC.”Journal of Policy

Analysis and Management23 (4): 671–95.

Hamilton, Gayle, Stephen Freedman, Lisa Gennetian, Charles

Michalopoulos, Johanna Walter, Dianna Adams-Ciardullo,

and Anna Gassman-Pines. “National Evaluation of

Welfare-to-Work Strategies.”2001. Prepared by MDRC,

Washington, DC for the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services and U.S. Department of Education.

Haskins, Ron. 2018, July 25. “Trump’s Work Requirements Have

Been Tested Before. ey Succeeded.” e Washington Post.

Hoynes, Hilary, Jesse Rothstein, and Krista Runi. 2017. “Making

Work Pay Better through an Expanded Earned Income Tax

Credit.” Policy Proposal 2017-09, e Hamilton Project,

Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

Hoynes, Hilary Williamson, and Schanzenbach, Diane Whitmore.

2012. “Work Incentives and the Food Stamp Program.”

Journal of Public Economics 96 (1): 151–62.

———. 2016, January. “e Safety Net as an Investment.” Working

Paper, University of California, Berkeley.

Institute of Medicine. 2003. “Spending on Health Care for

Uninsured Americans: How Much, and Who Pays?”

In Hidden Costs, Values Lost: Uninsurance in America,