Work Requirements and

Work Supports for Recipients of

Means-Tested Benefits

JUNE | 2022

Low Income

Workforce

Income

Development

Services

Families With

Sources

Training

Earnings

Benefits

Subsidized

Employment

Federal

Budget

Reduc d

Poverty

Deep

Single

Mothers

Welfare

Reform

Economic

Conditions

Enrollment

Cash

Payments

Federal

Funding

Goods Services

Policy

Options

of

Policies

Child

Care

Job-Search

Assistance

Temporary

Assistance

for Needy Families

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Medicaid

Unemployment

Rate

Budgetary

Savings

and

Barriers to Work

Participants

Online Tools

Years

Months

Programs

Work

Literature

Recipients

Able-Bodied

Adults

Aid

to

Families

Children

Dependent

With

Families

Children

Young

With

Poverty

Thresholds

At a Glance

In this report, the Congressional Budget Oce analyzes the eects of work requirements and work

supports on employment and income of participants in Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

(TANF), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and Medicaid. e agency also

assesses how changing work requirements and work supports in those programs would aect the

federal budget. In many cases, the size of those eects is highly uncertain.

Effects of Work Requirements on Employment, Income, and the Federal Budget

•

Making the receipt of benets contingent on working or preparing to work has substantially

increased the employment rate of the targeted recipients in TANF during the year after they enter

the program and by a smaller amount in later years. Work requirements in SNAP have increased

employment less; in Medicaid, they appear to have had little eect on employment.

•

Although some people have higher income because they work more to meet the programs’

requirements, other people do not meet the work requirements and are left with little income

from in-kind benets, cash payments, earnings, or other sources. Overall, the increase in total

earnings from TANF’s work requirements is about equal to the reduction in benets. In contrast,

work requirements in SNAP and Medicaid have reduced benets more than they have increased

people’s earnings.

•

In general, tightening work requirements would reduce federal spending by decreasing the amount

of benets provided; the extent of the budgetary savings would depend on the details of the policy.

If lawmakers used the savings from tightening work requirements to increase work supports that

helped recipients meet those requirements, the federal budget would change little (or perhaps not

at all).

Effects of Work Supports on Employment, Income, and the Federal Budget

•

Subsidized child care, job-search assistance, and subsidized employment have increased the

employment of recipients, whereas job training has had mixed results.

•

In addition to boosting recipients’ earnings, federal funding for work supports has freed up

income that recipients would have spent on those supports to instead be spent on other goods and

services.

•

If policymakers chose to expand work supports, they would need to provide additional funding.

Child care subsidies can cost several thousand dollars per recipient, whereas less intensive services

(such as assisting people who are searching for a job by providing access to literature and online

tools) generally cost less.

www.cbo.gov/publication/57702

Contents

Summary 1

How Do Work Requirements Aect People’s Employment and Income? 1

How Do Work Supports Aect People’s Employment and Income? 2

How Might Policymakers Change Work Requirements and Work Supports? 2

Chapter1: An Overview of Work Requirements, Work Supports, and Means-Tested Programs 5

Work Requirements and Work Supports in Recent Years 5

Changes to Work Requirements and Work Supports During the 1990s 6

Changes in Federal Spending and Enrollment 8

Chapter2: Eects of Work Requirements on People’s Employment and Income 11

TANF 11

SNAP 18

Medicaid 19

Chapter3: Eects of Work Supports on People’s Employment and Income 21

Subsidized Child Care 21

Workforce Development Services 22

Chapter4: Factors That Aect How Work Requirements and Work Supports Change

People’s Employment and Income 25

Participation in Work-Related Activities in the Absence of Work Requirements and Work Supports 25

Barriers to Work 26

Economic Conditions 27

Chapter5: Options for Changing Work Requirements and Work Supports 31

Two Options That Would Expand Work Requirements 31

Two Options That Would Reduce Work Requirements 33

Two Options That Would Expand Work Supports 34

One OptionThat Would Decrease Work Supports 37

iv WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS JUNE 2022

Boxes

1-1. How Are Means-Tested Programs Funded? 9

2-1. How Policy Changes Made to Means-Tested Programs During the 1990s Aected

Single Mothers’ Employment 13

AppendixA: Sources of Income for Families 24Months After They Start Receiving Cash Assistance 39

The SIPP Data That CBO Used 39

CBO’s Approach to Analyzing the SIPP Data 39

Families’ Sources of Income 24Months After Receiving Cash Assistance 41

AppendixB: The Eects of Work Requirements on People’s Employment and Income in Recent Years 43

The HHS Data That CBO Used 43

Eects of Work Requirements When the Unemployment Rate Is High 44

Eects of Work Requirements on Families With Young Children 44

List of Tables and Figures 52

About This Document 53

Notes and Definitions

To complete and publish this report promptly, the Congressional Budget Oce used its

July2021baseline for the analysis. CBO expects that the ndings would be similar had the analysis

used the agency’s most recent baseline (published in May2022).

Unless this report indicates otherwise, all years referred to are federal scal years, which run from

October1 to September30 and are designated by the calendar year in which they end.

Numbers in the text, tables, and gures may not add up to totals because of rounding.

Projected future costs and the other dollar gures in the options are in nominal dollars. All other

dollar gures are expressed in 2019 dollars, using the price index for personal consumption expendi-

tures from the Bureau of Economic Analysis to remove the eects of ination.

Some of the gures in this report use shaded vertical bars to indicate periods of recession. (A recession

extends from the peak of a business cycle to its trough.)

References to states include the District of Columbia.

A TANF recipient is a person who receives recurring cash payments through the Temporary

Assistance for Needy Families program. Data on the recipients of other forms of assistance provided

by TANF, such as job training, are limited.

Intensive job-search assistance is generally provided in person, such as through workshops or one-on-

one career counseling.

An able-bodied adult is a person over the age of 17who does not receive disability benets (either

through Supplemental Security Income or Disability Insurance).

A parent is a person who lives with one or more dependents under the age of 18.

A child is a dependent who is under the age of 18.

Cash income generally consists of earnings, business income, income from savings, child support,

and cash payments from means-tested programs, Social Security, and unemployment insurance. at

measure of economic well-being is similar to what the Census Bureau uses to determine the ocial

poverty rate.

Income includes cash income, in-kind benets from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,

and refundable tax credits. at measure of economic well-being is similar to what the Census Bureau

uses to determine the Supplemental Poverty Measure.

Poverty thresholds are used by the Census Bureau to determine the ocial poverty rate. e thresh-

olds are based on family income and dier for families of dierent sizes.

vi WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS JUNE 2022

Deep poverty is when a family’s cash income is less than half of the applicable poverty threshold.

Welfare reform is the term for a series of actions that policymakers took in the mid-1990s to encour-

age employment among benet recipients and shorten the duration of benet receipt. It consisted of

executive actions that introduced work requirements in Aid to Families With Dependent Children

(the program that preceded TANF) and implementation of provisions of the Personal Responsibility

and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act.

Summary

e federal government has many programs that are

designed specically to help people who have relatively

low income obtain food, health care, housing, and other

goods and services that they might not otherwise be

able to aord. ose means-tested programs provide

cash payments or other assistance to qualied recipients.

If recipients’ earnings rise, then their benets typically

decline. To counter that incentive for participants to

work less, the programs often incorporate work require-

ments (which make the receipt of benets contingent

on working or preparing to work) and work supports

(which make working more feasible and protable for

participants). Work support programs usually also have

work requirements. (For example, only people who work

are eligible for the earned income tax credit.)

is report focuses on work requirements and work

supports in three federal programs: Temporary Assistance

for Needy Families (TANF), the Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program (SNAP), and Medicaid. Of those

programs, TANF is the smallest, providing monthly

cash payments to about 1million families each year. By

law, most able-bodied parents who receive those benets

must participate in work-related activities. SNAP and

Medicaid serve much broader and larger populations

than TANF; they also have included work requirements

at times, but typically applied them only to able-bodied

adults without dependents. To support recipients who

are working or searching for work, policymakers have

made subsidized child care and workforce development

services available to some participants in those programs,

particularly TANF.

In this report, the Congressional Budget Oce analyzes

how work requirements and work supports aect the

employment and income of former, current, and poten-

tial participants. In addition, the agency estimates how

changes to those requirements and supports would aect

the federal budget over the next nine years. Even though

research suggests that means-tested programs can con-

tinue to aect former participants for many years, this

report focuses on the programs’ more immediate eects.

How Do Work Requirements Aect

People’s Employment and Income?

TANF’s work requirements have generally increased

employment while having little eect (on net) on average

income. Some recipients have earned more by getting a

job, but others have lost benets without nding work,

which probably increased the number of people in deep

poverty. Work requirements in SNAP and Medicaid have

also reduced the benets that people receive but have

increased their employment or earnings less (for SNAP

recipients) or maybe not at all (for Medicaid recipients).

TANF recipients facing work requirements have been

provided with strong work supports, unlike SNAP and

Medicaid recipients.

TANF

Most of the research on work requirements focuses on

single mothers who received recurring cash payments

through TANF or its predecessor, Aid to Families With

Dependent Children. e imposition of work require-

ments in the 1990s boosted the employment of those

single mothers but had little eect on their average

income, mainly because the increase in earnings for those

who worked was about equal to the reduction in cash

payments for those who lost benets. e number of

people receiving cash payments has continued to decline

over the past two decades; by 2019, the number of recip-

ients was about 2million, or one-seventh of what it had

been in 1993.

Although TANF’s work requirements have probably had

little eect on average income among single mothers,

those requirements have probably changed how income

is distributed among that group. e mothers who

gained employment often saw their income boosted by

higher earnings and receipt of additional tax credits, but

many mothers who lost benets because they did not

meet the work requirements were left in deep poverty.

TANF continues to be the primary source of recurring

cash assistance for able-bodied single mothers without

education beyond high school, but the percentage of

those mothers who are receiving assistance has fallen

along with the total number of recipients.

2 WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS JUNE 2022

Before work requirements were imposed, nearly all

less-educated single mothers who did not work for an

extended period received cash payments. By calendar

year 2019, though, about one-seventh of less-educated

single mothers had no earnings and no cash assistance,

CBO estimates. Many of those families report hav-

ing almost no income beyond benets from SNAP.

By removing families from TANF before they found

work—and by deterring families from entering the pro-

gram—work requirements have probably played a role in

increasing the number of families in deep poverty.

SNAP

SNAP’s work requirement has probably boosted employ-

ment for some adult recipients without dependents but

has reduced income, on average, across all recipients.

Earnings increased among recipients who worked more,

but far more adults stopped receiving SNAP benets

because of the work requirement. Most of the adults

who had their SNAP benets terminated for failing to

comply with the work requirement have very low income

because few of them have earnings or receive cash

payments.

Medicaid

Evidence of the eect of work requirements on Medicaid

recipients is limited to Arkansas, the only state where a

work requirement was imposed on recipients for more

than a few months. ere, many of the targeted adults

lost their health insurance as a result of the work require-

ment. Employment did not appear to increase, although

the evidence is scant. Research indicates that many par-

ticipants were unaware of the work requirement or found

it too onerous to demonstrate compliance.

How Do Work Supports Aect

People’s Employment and Income?

Most work supports increase employment and income.

Subsidized child care, for instance, benets single parents

(its main recipients) by boosting their employment and

increasing their resources substantially. Parents who nd

employment benet from higher earnings, and those

who would have purchased child care even without a

subsidy have more income to spend on other goods and

services. (e resources of some working parents are

unaected because they would have had a relative or

friend watch their children in the absence of the subsidy.)

Job-search assistance and subsidized employment

provided by workforce development programs have

increased employment and income, but job training

provided by those programs has had mixed results.

According to a study conducted by the Department of

Labor in the early 2010s on two of the largest workforce

development programs, intensive job-search assistance

(such as career counseling) increased participants’

average earnings by about $2,200in the year following

the receipt of assistance. In contrast, job training could

reduce employment and income by causing participants

to delay their job search or by reducing the number of

hours they work. In the Department of Labor’s study,

participants in job-training programs worked less while

in training and did not work more or earn more after-

ward, on average.

Lawmakers modied the large workforce development

programs in 2014 to better align job training with the

demands of local employers. A comparable evaluation

of those programs’ eectiveness since then might show

increased employment and income from job-training

programs if the alignment between those programs

and labor market demand has improved lately. Recent

research demonstrates that job training provided by

smaller programs can increase employment and income

when it focuses on the demands of local employers.

How Might Policymakers Change

Work Requirements and

Work Supports?

To increase employment, raise income, or reduce federal

spending, the Congress could pursue various options

that would change work requirements and work sup-

ports. ose options fall into four broad categories.

Options in a category would typically accomplish similar

objectives, although the eects of any particular option

on employment, income, and the federal budget would

depend on its details (see Table S-1).

•

Options that expanded work requirements would

typically increase employment. But they would

have little eect on recipients’ average income (net

of medical expenses, in the case of Medicaid) or

would reduce it because the overall loss in benets

would equal or exceed the total gain in earnings

from increases in employment. Some participants’

earnings would increase more than their benets

decreased; other participants would be left without

any earnings or benets. If the work requirements

were tied to receipt of SNAP or Medicaid, the

loss in benets would reduce federal spending

3SUMMARY WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS

because the government pays for a xed portion

of the cost of those benets. In this analysis, CBO

assessed expanding work requirements in SNAP and

Medicaid. e SNAP option that CBO discusses in

this report might not reduce federal spending because

it includes additional spending on work supports.

e other option would substantially increase the

amount that people who lost Medicaid coverage pay

out of pocket for medical services.

•

Options that reduced work requirements would

typically increase federal spending on benets

and reduce employment. ey would decrease

the number of people with very low income and

would either raise average income or change it

little. Reducing work requirements during periods

of high unemployment could boost recipients’

income substantially while having little eect on

employment. In this analysis, CBO assesses reducing

work requirements in SNAP and TANF. e TANF

option would not increase federal spending because

that program’s funding is set at a xed total.

•

Options that expanded work supports would typically

lead to larger gains in income than options that

expanded work requirements, but they would also

push up federal spending. In addition, they would

increase employment and reduce recipients’ expenses

for work supports, leaving them with more income

to spend on other goods and services. In this analysis,

CBO assesses one option that would provide more

workforce development services to TANF recipients

when jobs are scarce and a second option that would

generally increase funding for subsidized child care.

•

Options that reduced work supports would typically

lead to less employment, lower income, and reduced

federal spending. In this analysis, CBO assesses an

option that—rather than reducing federal spending—

would shift funding from work supports to cash

payments for nonworking families. Such a policy

would reduce employment but could raise recipients’

income and make deep poverty less prevalent.

Table S-1 .

Typical Eects of Changing Work Requirements and Work Supports,

by Broad Category of Options

Option

Category

Typical Eects on People Subject to the Change

Typical Eect on

Federal SpendingEmployment Income and Expenses

Expand Work Requirements Increase Average income would change

little or decrease; more people

would have very low income

Decrease

Reduce Work Requirements Decrease Average income would change

little or increase; fewer people

would have very low income

Increase

Expand Work Supports Increase Increase income and decrease

expenses

Increase

Reduce Work Supports Decrease

Decrease income and increase

expenses Decrease

Source: Congressional Budget Oce.

Work supports consist of subsidized child care and workforce development services, such as job-search assistance, job training, and subsidized employment.

The eects of a particular option would depend on its details.

Chapter1: An Overview of Work

Requirements, Work Supports, and

Means-Tested Programs

e federal government has many programs that provide

benets to help people who have relatively low income.

Such means-tested programs—some of which are admin-

istered jointly with the states—help the people who

receive those benets obtain goods and services that they

might not otherwise be able to aord. ree of those

programs are Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

(TANF), which funds monthly cash payments along

with many other services; the Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program (SNAP), which assists people in

purchasing food; and Medicaid, which provides health

insurance.

Although the people served by those programs dier,

they generally have cash income near or below the

poverty line (see Table 1-1). Most families in TANF,

for instance, are headed by single mothers who have no

education beyond high school; despite the cash pay-

ments they receive from the program, they have very

low cash income—in many cases, it is so low that they

are considered to be in deep poverty. Income for SNAP

and Medicaid recipients is still low but not as low, and a

greater share of adults in those programs are married or

childless. (In addition, many of those adults are elderly

or disabled.)

In 2019, TANF provided cash payments of about $500a

month, on average, to participating families consisting

of an able-bodied parent and two children—an amount

equal to roughly 30percent of the poverty threshold.

SNAP provided a monthly food allowance of $372, on

average.

1

Average government spending on health care

for such a family in Medicaid was higher—at roughly

$800per month—but was concentrated among recipi-

ents with severe medical conditions.

1. e maximum SNAP benet increased by slightly more than

20 percent in October 2021. In contrast, TANF benets have

not risen recently in most states and are unlikely to substantially

increase in the future because federal funding for that program is

not scheduled to rise.

By design, benet amounts in TANF and SNAP decline

rapidly as participants’ earnings increase. at structure

can create an incentive for participants to work less,

although additional tax credits can oset a substantial

portion of that decline.

2

e decrease in benets tends

to be largest for families in TANF, who receive about

50cents less in cash payments for each additional dollar

they earn.

Work Requirements and Work

Supports in Recent Years

To encourage participants in TANF, SNAP, and

Medicaid to work, policymakers have added require-

ments to those programs. To receive benets, participants

must demonstrate that they are working or preparing

to work. Most adults in TANF are required to work

or participate in related activities, such as searching or

training for a job. A far smaller portion of adults in

SNAP are subject to such a requirement: Many SNAP

recipients are elderly or disabled and thus not expected

to work, and the requirement is not imposed on house-

holds that include dependent children. Medicaid does

not have work requirements, although Arkansas imposed

a work requirement on some childless adults who receive

Medicaid benets in 2018. (Several other states began

implementing work requirements for Medicaid recip-

ients, but Arkansas was the only state that terminated

Medicaid benets because of insucient employment.)

3

To make work more feasible and protable, the fed-

eral government provides funds (often directly to the

2. For more details, see Congressional Budget Oce, Eective

Marginal Tax Rates for Low- and Moderate-Income Workers in

2016 (November 2015), www.cbo.gov/publication/50923.

3. e Trump Administration encouraged states to apply for

waivers that would allow them to impose work requirements

on Medicaid recipients and then approved the applications

of 10 states. However, the Biden Administration rescinded

those approvals before most of the states had implemented the

proposed requirements.

6 WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS JUNE 2022

states) for work supports, such as subsidized child care

and workforce development services. ose services

are primarily funded by the Child Care Development

Fund (CCDF), Title 1 of the Workforce Innovation and

Opportunity Act (WIOA), and TANF. (All those fund-

ing sources focus assistance on people with low income,

although not exclusively on TANF, SNAP, and Medicaid

recipients.)

In 2019, the CCDF funded $8billion of subsidized

child care; by providing state-run care for dependent

children, those programs enabled the parents to work,

train, or search for a job.

4

at same year, Title 1 of

WIOA funded $5billion of workforce development

services, including job-search assistance, job training,

and subsidized employment. TANF provided $3billion

for subsidized child care and $3billion for workforce

development services in 2019. Other programs that

provide work supports to families in TANF, SNAP, and

Medicaid and that also aect people’s incentives to work

(such as Head Start, the child tax credit, and the earned

income tax credit, or EITC) are beyond the scope of

4. e Congress temporarily increased CCDF funding in 2020 and

2021 in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

this report.

5

(CBO used 2019as a proxy for what work

requirements and supports will look like after the public

health emergency declaration related to the coronavirus

pandemic is lifted.)

Changes to Work Requirements and

Work Supports During the 1990s

e most signicant changes to employment of partici-

pants in means-tested programs occurred in the 1990s,

when work requirements and work supports were sub-

stantially expanded for many participants. e changes

were implemented through a series of executive actions

followed by enactment of the Personal Responsibility

and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA)

in 1996. ose legislative changes are collectively referred

to as welfare reform.

5. Head Start provides free care and education for the young

children of parents with low income. e EITC was designed

to encourage people to work by providing a refundable tax

credit that initially increases as earnings rise. e child tax credit

also encourages work in the same way (although it temporarily

stopped functioning as a work support in 2021 because the

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 made it available to all

families with qualifying children regardless of their earnings).

Table 1-1 .

Characteristics of Selected Means-Tested Programs, 2019

Recipient Households

Headed by Single Parents

(Percent)

Typical Benet for a Parent and

Two Children (2019 dollars)

Highest Monthly

Income Eligible

a

Average Monthly

Benet

Change in Benet per

Dollar of Earnings

TANF

b

66 1,138 504 -0.50

SNAP 25 2,252 372 -0.24

Medicaid

c

25 2,453 800 Small

Source: Congressional Budget Oce, using data from the Urban Institute and the Department of Health and Human Services.

See www.cbo.gov/publication/57702#data.

In 2019, the federal poverty threshold for a family of three (a single parent and two children) was $1,716 per month.

SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

a. These amounts are gross income limits for initial eligibility, which typically disregard some earnings and other sources of income. Applicants must also meet a

net income standard, which further restricts the eligibility of people who do not have much income that qualifies for exclusion.

b. CBO used benefits in Washington to represent TANF benefits because that state has an income threshold, average benefit, and relationship between benefits

and earnings that are close to the average of all states.

c. Medicaid benefits are measured in terms of the payments that federal and state governments make for the medical care of recipients. In most states,

Medicaid benefits do not change as earnings increase until families reach the eligibility threshold. At that point, families lose eligibility for Medicaid but can

get heavily subsidized insurance through the marketplaces established under the Aordable Care Act.

7CHAPTER 1: AN OVERVIEW WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS

Before those changes were implemented, the government

provided cash payments to qualifying recipients through

Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC). Into

the early 1990s, that program had only minimal work

requirements. From 1993 through 1996, most states

imposed their own work requirements on AFDC partici-

pants by using waivers provided by the Bush and Clinton

Administrations. In 1997, as a result of PRWORA,

TANF replaced AFDC. For a family to receive cash pay-

ments from TANF, all able-bodied parents in it generally

must participate in work-related activities. PRWORA

also imposed a work requirement on able-bodied adults

without dependents in SNAP.

Welfare reform substantially increased the amount of

work supports available to participants in means-tested

programs. PRWORA consolidated four child care

assistance programs into the CCDF and added $1bil-

lion in funding. (All gures are in 2019dollars.) It also

allowed states to reallocate TANF funding from cash

payments to work supports and other services. e states

have used that discretion to drastically change the types

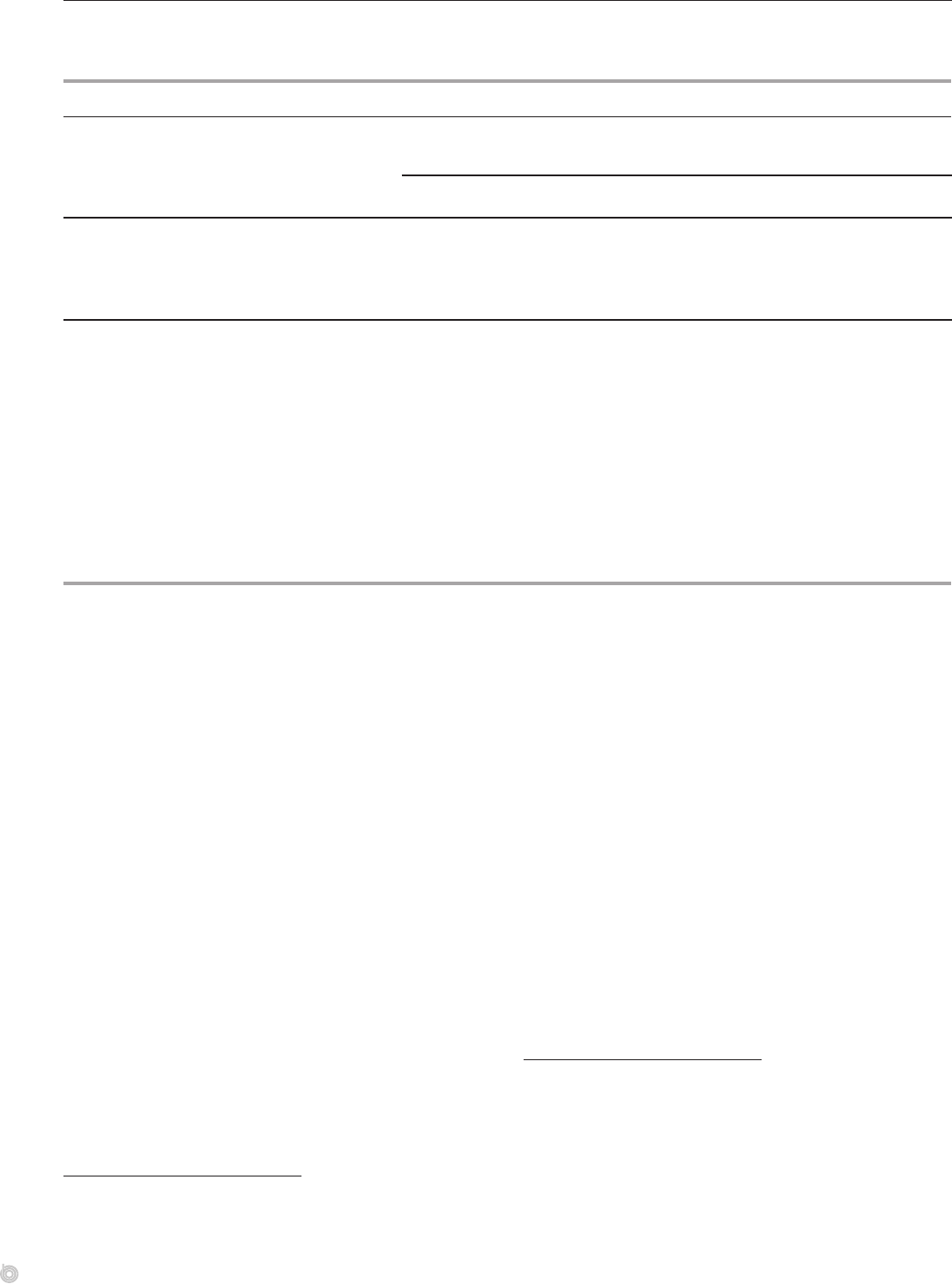

of assistance TANF provides. In 1996, for example,

about 84percent (or $31billion) of the federal and

state funding for the programs that preceded TANF

was spent on recurring cash payments, whereas about

5percent (or $2billion) was spent on work supports (see

Figure 1-1). By 2019, states had allocated about 51per-

cent (or $14billion) of TANF funding to work supports.

In addition, states reallocated funding for recurring cash

payments to a wide array of other services, leaving only

about 23percent (or $7billion) of TANF funding for

those recurring cash payments in 2019.

6

Welfare reform coincided with a large increase in the

EITC, which also supports work. e Omnibus Budget

Reconciliation Act of 1993roughly tripled the maxi-

mum credit for families with two or more children and

roughly doubled the maximum credit for families with

one child. ose increases were phased in from 1994

through 1996. In addition, policymakers created the

6. States spent the remaining 26 percent of TANF funding on

a broad array of other services, including initiatives to reduce

out-of-wedlock pregnancies, encourage two-parent families, and

support the foster care system.

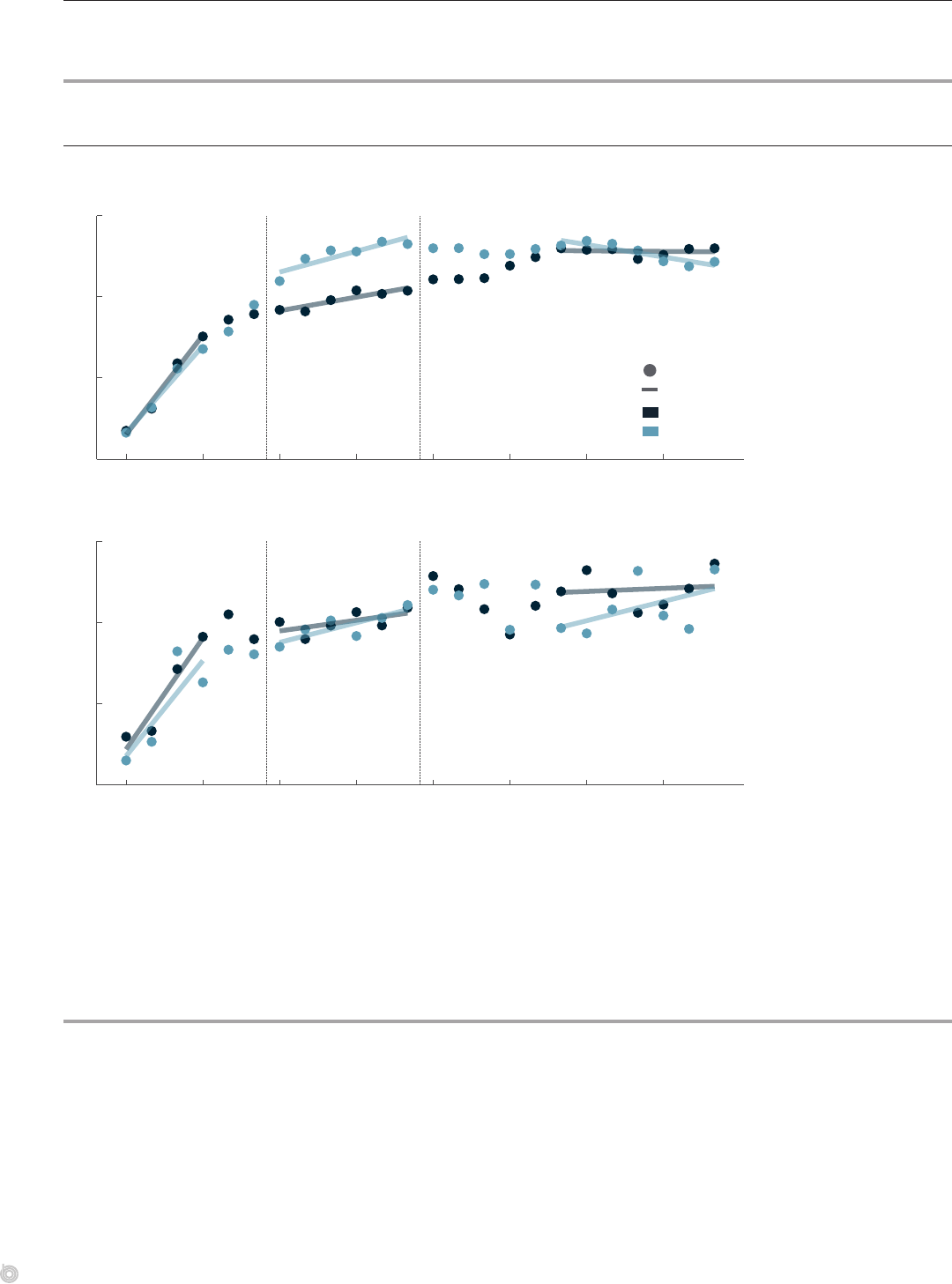

Figure 1-1 .

Spending for TANF and the Programs That Preceded It, by Type of Assistance

Percentage of Total Spending

0

25

50

75

100

1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019

Other Services

TANF replaces AFDC

Recurring Cash

Assistance

Work Supports

Data source: Department of Health and Human Services. See www.cbo.gov/publication/57702#data.

Before the creation of TANF in 1997, AFDC distributed recurring cash assistance, the Job Opportunities and Basic Skills Training program provided work support,

and the Emergency Assistance program supplied other services for low-income families.

Costs to administer the program and monitor compliance with eligibility rules are distributed proportionally among the three types of assistance.

AFDC = Aid to Families With Dependent Children; TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

States used the flexibility

provided by TANF to

shift funding from cash

assistance to work

supports, including

subsidized child care.

8 WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS JUNE 2022

child tax credit in 1998. at credit was available to few

working families with low income before 2001, however.

Changes in Federal Spending and

Enrollment

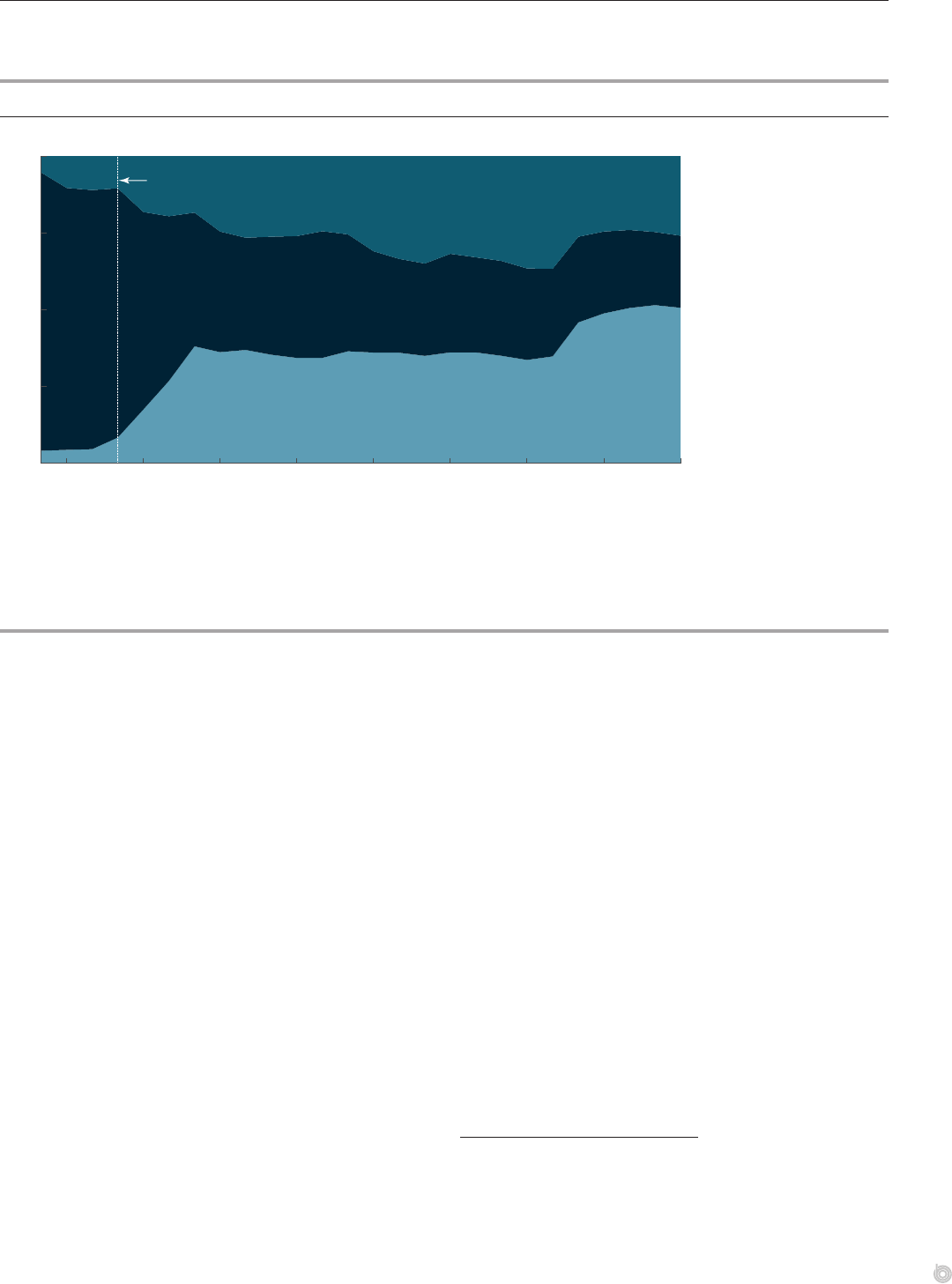

Over the past few decades, federal spending on SNAP

and Medicaid has increased substantially, whereas

spending on AFDC/TANF has fallen drastically (see

Figure 1-2). In 1989, the federal government spent

$63billion on Medicaid, compared with roughly

$20billion each on SNAP (which was known as the

Food Stamp program at that time) and AFDC. (Again,

all gures are in 2019dollars.)

Medicaid spending exceeded spending on the other

programs in 1989largely because health care coverage

was much more costly than other benets, a trend that

has persisted. Spending per enrollee and the number of

enrollees in Medicaid have increased substantially since

1989, bringing the program’s total federal spending to

$409billion in 2019(in addition to the $221billion

states spent on the program in that year).

Federal spend-

ing on SNAP has also increased (to $60billion in 2019),

driven mostly by a rise in the number of recipients.

7

For

Medicaid and SNAP, funding has been adjusted over

7. In 2019, states spent $4 billion on administrative costs for SNAP.

Figure 1-2 .

Federal Spending for Selected Means-Tested and Work Support Programs

Billions of 2019 Dollars

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019

0

5

10

15

1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019

SNAP

Medicaid

AFDC/TANF

a

Means-Tested Programs

Work Support Programs

CCDF

a

WIOA

a

Over the past few decades,

federal spending on SNAP

and Medicaid has increased

substantially, whereas

spending on AFDC/TANF

has fallen from $20 billion

to $16 billion. The CCDF and

WIOA have each provided

about $5 billion per year in

work supports.

Data source: Congressional Budget Oce. See www.cbo.gov/publication/57702#data.

Work supports are funded by the CCDF (subsidized child care), WIOA (workforce development services), and TANF (subsidized child care and workforce

development services). The transfers that states make from TANF to the CCDF are only included as spending on TANF. Amounts for WIOA are appropriations

because data on spending were not available.

CCDF = Child Care Development Fund; SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families; WIOA = Workforce

Innovation and Opportunity Act.

a. Includes spending on predecessors: the Child Care Development Block Grant for the Child Care Development Fund, the Workforce Innovation Act and the Job

Training Partnership Act for the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, and Aid to Families With Dependent Children for Temporary Assistance for Needy

Families. The WIOA and its predecessors funded a wide range of programs.

9CHAPTER 1: AN OVERVIEW WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS

the years so that benets are available to everyone who

applies for and qualies for the programs (see Box 1-1).

Spending on SNAP has also uctuated because of

changes in food prices and how those changes aect the

benets provided.

Funding for TANF, CCDF, and WIOA is handled

dierently. Lawmakers furnish a specic amount of

money for those programs each year, which might not be

sucient to provide benets to all qualied applicants.

Since TANF was implemented in 1997, lawmakers have

not increased the nominal amount of the state family

assistance grant, which provides states with most of

their funding for the program; that value has been and

remains at about $16.5billion. Because the amount

has not been raised to account for ination, in eect

the value of the program’s funding has fallen by about

30percent since 1997.

8

(To receive all that funding,

states are required to spend a certain minimum amount

of their own funds on the program. at amount is also

8. e decline in the ination-adjusted value of funding for TANF

exceeds the decline in the value of spending for the program

because several states did not spend all the funding that they

received in the program’s rst two years.

not adjusted for ination; it has been and remains at

about $10billion.) Lawmakers have increased funding

for CCDF and WIOA on multiple occasions. ose

nominal increases have elevated the ination-adjusted

value of CCDF and approximately maintained it for

WIOA.

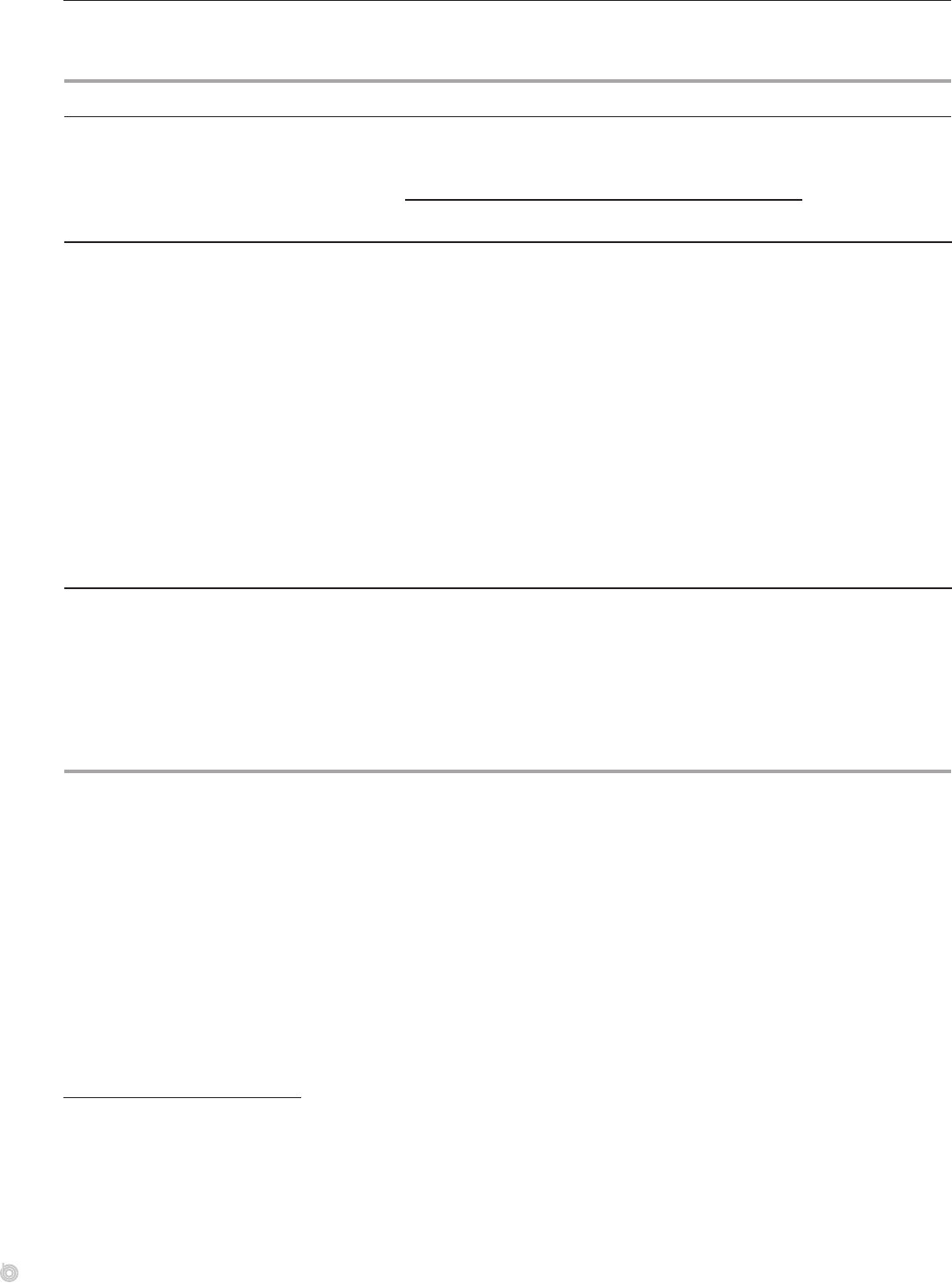

Enrollment in Medicaid and SNAP has risen substan-

tially over the past three decades, but enrollment in

AFDC/TANF has plummeted (see Figure 1-3). In 1989,

Medicaid and SNAP had about 20million recipients

each in an average month, and about 10million peo-

ple received cash payments through AFDC. Over the

subsequent 30years, enrollment has changed for each

program.

•

Medicaid. Enrollment has skyrocketed as lawmakers

have repeatedly expanded eligibility for the program,

including 2014’s expansion under the Aordable

Care Act. e number of Medicaid recipients has

roughly tripled since 1989, reaching 75million (or

about one-quarter of the U.S. population) during an

average month in 2019.

Box 1-1 .

How Are Means-Tested Programs Funded?

Means-tested programs are funded in various ways. Lawmak-

ers furnish a specific amount of money for Temporary Assis-

tance for Needy Families (TANF), which is primarily provided

in the form of a block grant. The state family assistance grant,

which totals about $16.5billion, has accounted for 95percent

of TANF’s federal funding in most years. In recent years, the

contingency fund has provided around $600million in addi-

tional funding.

1

Funding for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP) is handled dierently. The amount of money appropri-

ated for SNAP each year is intended to cover the cost of pro-

viding benefits to all people who apply for and are eligible for

the program. If the appropriated amount does not cover those

costs, lawmakers would need to appropriate additional funds,

1. The contingency fund is a mechanism that can increase the amount of TANF

funding available to states that are experiencing economic downturns. For

additional details on the funding of TANF, see Congressional Budget Oce,

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Spending and Policy Options

(January 2015), www.cbo.gov/publication/49887.

or the Administration would have to cut benefits. There has not

been any need to use supplemental appropriations or to imple-

ment any reduction in benefits in recent years. (Supplemental

appropriations were last provided about 30years ago.)

Medicaid is an entitlement, which means that federal funding

for medical services provided to eligible individuals is open-

ended. Funding for the program adjusts automatically as

enrollment or costs per enrollee change.

All three programs are jointly financed by the federal govern-

ment and state governments. To varying degrees, states fund a

portion of the services provided through TANF, SNAP, and Med-

icaid. TANF has a maintenance-of-eort requirement, which is

designed to limit the extent to which federal funding displaces

money that state governments would otherwise have spent on

the program. In contrast, states cover a share of the adminis-

trative costs for SNAP, which include employment and training

services. For Medicaid, states cover a share of the costs of the

services provided by the program in addition to a share of the

administrative costs.

10 WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS JUNE 2022

•

SNAP. Participation rose substantially in the 2000s,

primarily as a result of outreach initiatives. In general,

participation in the program tends to uctuate, rising

during and after recessions and diminishing when the

unemployment rate is low.

9

•

TANF. Participation has dropped drastically

since the onset of welfare reform, having fallen

by 85percent from 1993 to 2019. Some of that

decrease can be attributed to rising earnings among

single mothers, but it primarily has been driven

by declining participation among families whose

income is low enough for them to qualify for the

9. For more details on how participation in SNAP has changed over

the years, see Congressional Budget Oce, e Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (April 2012), www.cbo.gov/

publication/43173.

program. PRWORA contributed to the decline in

the participation rate through the changes it made to

AFDC/TANF.

10

10. Since before 1997, many states have not increased the nominal

value of the maximum payment available in TANF, even though

the rising cost of living has eroded the value of that payment

by about 30 percent. A growing number of income-eligible

families appears to nd those payments an inadequate incentive

to go through the process of demonstrating eligibility for the

program—a process made more onerous by the imposition of

the work requirements. See Zachary Parolin, “Decomposing

the Decline of Cash Assistance in the United States, 1993 to

2016,” Demography, vol. 58, no. 3 (April 2021), pp. 1119–1141,

https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-9157471. PRWORA has

contributed to states’ not maintaining the purchasing power of

benets by converting the funding mechanism into a grant of

constant nominal value and by allowing states to divert most of

that money from cash payments to a wide array of other services.

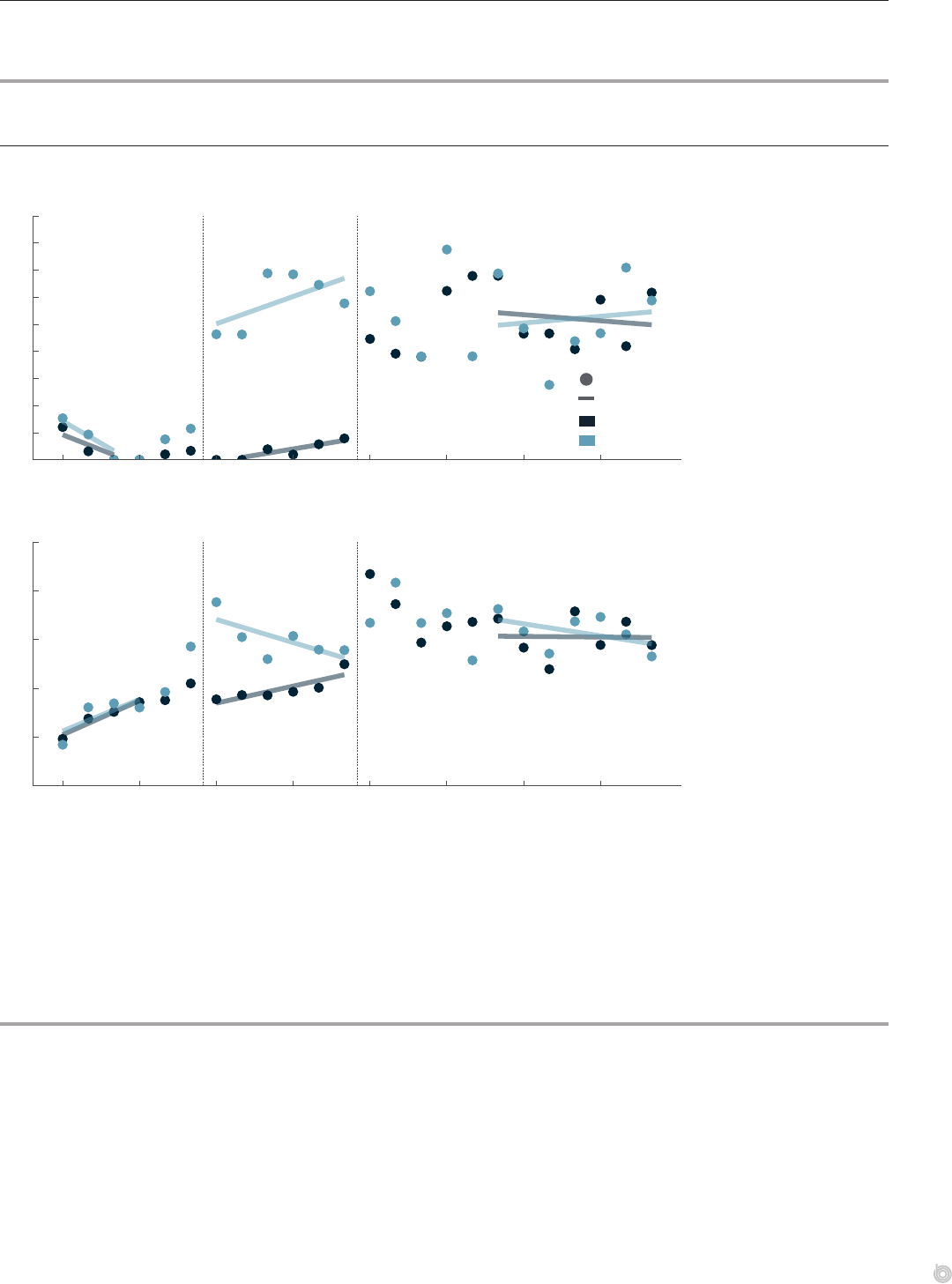

Figure 1-3 .

Participation in Selected Means-Tested and Work Support Programs

Millions of People

0

20

40

60

80

1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019

SNAP

Medicaid

TANF

a

CCDF

Even though enrollment

in Medicaid and SNAP

has risen greatly over the

past three decades, the

number of people receiving

recurring cash payments

has plummeted.

Data source: Congressional Budget Oce. See www.cbo.gov/publication/57702#data.

Data for the CCDF were not available before 1998. CBO did not compile participation data for the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act because

participation in the programs it funds can range from a brief self-directed job search to a full year of intensive job training with income support.

CCDF = Child Care Development Fund; SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

a. Consists of recipients of recurring cash assistance and includes participants in its predecessor, Aid to Families With Dependent Children.

Chapter2: Eects of Work Requirements

on People’s Employment and Income

e eects of work requirements vary among partici-

pants in dierent means-tested programs. Most of the

research conducted on those eects has focused on work

requirements in the Temporary Assistance for Needy

Families program and its predecessor, Aid to Families

With Dependent Children, in the 1990s, when wel-

fare reform greatly altered those programs. Evidence of

the eects of work requirements in the Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program and Medicaid is more

limited.

Overall, available evidence indicates that the eects of

work requirements on employment and income probably

dier among the three programs.

1

In addition, the gain

in employment among program participants who are

subject to work requirements is probably oset in part

by temporary reductions in employment among people

who are not subject to the requirements.

2

e analysis

in this chapter is mostly based on data from the annual

1. is report focuses on changes in employment and income

within the standard period used for the Congressional budget

process, which extended through 2031 when this report

was prepared. Evidence of the longer-term eects of work

requirements and supports is limited, although research

indicates that access to SNAP benets during childhood tends

to increase earnings in adulthood. See Marianne P. Bitler

and eodore F. Figinski, Long-Run Eects of Food Assistance:

Evidence From the Food Stamp Program (August 2019),

https://tinyurl.com/2p974kdj (PDF, 9.2 MB). us, work

requirements that terminate benets for families with children

might reduce their earnings later in life.

2. Most of the research on unemployment insurance indicates

that policies that increase employment by encouraging people

to search for a job decrease employment among people not in

the program. Such spillovers are probably rarer when jobs are

plentiful, and those studies were conducted during periods

of high unemployment. For example, see Ioana Marinescu,

“e General Equilibrium Impacts of Unemployment

Insurance: Evidence From a Large Online Job Board,”

Journal of Public Economics, vol. 150 (June 2017), pp. 14–29,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.02.012.

supplement to the Census Bureau’s Current Population

Survey, so the numbers provided are for calendar years.

TANF

Nationwide, most adults in TANF are required to

participate in work-related activities. Specically, the

federal government requires a certain percentage of

able-bodied parents of children receiving monthly cash

payments—50percent, before adjustments are made—to

either have sucient hours of employment or participate

in approved activities that could lead to employment,

such as vocational training. Any state that does not meet

that work standard risks having its federal funding for

the program reduced, so states typically decrease or ter-

minate a family’s benets if the parent’s work hours are

not sucient. Many states have chosen to impose more

stringent work requirements even when they do not

appear to be at risk of violating the work standard.

In general, those work requirements have increased

employment, which has substantially boosted the income

of some single mothers.

3

(Most TANF recipients are

in families headed by single mothers.) e number of

people receiving cash payments in TANF has declined

by about 85percent since the mid-1990s, however, and

many single mothers have very low income because they

are not working or receiving assistance. (is analysis

focuses on parents who do not receive disability benets,

because they are most likely to be subject to the work

requirements.)

Employment

Most TANF families are headed by single mothers with

no education beyond high school. Employment among

that group rose substantially in the 1990s, in part

3. Initially, AFDC only provided benets to single mothers or the

wives of men who were unable to work. Eligibility was extended

to single fathers and families with two able-bodied parents before

the transition to TANF. However, participation in the programs

has remained low among those groups.

12 WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS JUNE 2022

because of the widespread imposition of work require-

ments. In the years leading up to welfare reform, single

women without education beyond high school were

far less likely to be employed if they had a child (see

Figure 2-1).

4

From 1993 to 2000, though, the employ-

ment rate for less-educated single mothers increased by

16percentage points (rising from 52percent to 68per-

cent), whereas the employment rate of their childless

counterparts increased by only 4percentage points.

During those years, many states added work require-

ments to AFDC (from 1993 to 1996), all states transi-

tioned from AFDC to TANF (in 1997), and states that

did not have work requirements already in place started

imposing them in TANF (from 1997 to 1999).

Although work requirements accounted for some of the

16percentage-point increase in employment from 1993

to 2000, most of the increase was probably the result of

4. Families of women without dependents are not eligible for

cash payments from TANF. Because such childless women are

largely unaected by TANF, they are used as proxies for how the

employment and income of single mothers without education

beyond high school would have changed in the absence of welfare

reform.

other policy changes (see Box 2-1). Experimental evalu-

ations conducted in AFDC waiver programs during the

1990s indicate that work requirements similar to those in

TANF, when combined with increases in work supports,

increased the employment rate by about 5percentage

points over ve years.

5

TANF’s work requirements have continued to boost

employment for the single parents who have entered the

program in recent years, according to the limited evi-

dence that is available. Since 2000, the employment rate

of single mothers without education beyond high school

has remained relatively steady, moving in tandem with

5. e experimental evaluations compared recipients who were

randomly assigned to a combination of work requirements,

intensive job-search assistance, and additional subsidized

child care with recipients of the standard array of assistance.

For a summary of the ndings of those evaluations, see Gayle

Hamilton and others, National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work

Strategies (submitted by Manpower Demonstration Research

Corporation to the Department of Health and Human Services,

December 2001), p. 86, https://tinyurl.com/2p89s5ad. e

Congressional Budget Oce estimated the employment eects

from evaluations of programs that focused on labor force

attachment because that is TANF’s focus.

Figure 2-1 .

Employment Rates for Single Women With No Education Beyond High School,

by Presence of Children

Percent

0

20

40

60

80

1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019

With Children

Without Children

The employment rate

for less-educated single

mothers—the primary group

served by Aid to Families

With Dependent Children

and Temporary Assistance

for Needy Families—rose

substantially in the 1990s

after work requirements

were added to the cash

assistance programs

and work supports were

increased.

Data source: Census Bureau, Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey, from IPUMS-USA. See www.cbo.gov/

publication/57702#data.

The data are by calendar year and are limited to unmarried women between the ages of 18 and 61 who have no postsecondary education, are not students, and

are not receiving disability benefits. The employment rates are for March of the specified year.

13CHAPTER2: EFFECTS OF WORK REQUIREMENTS ON PEOPLE’S EMPLOYMENT AND INCOME WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS

the rate of their childless counterparts. But the changes

to work requirements have been gradual enough that

their eects on employment are obscured by 20years of

changes in the economy and other labor market policies.

6

To bolster the available evidence, the Congressional

Budget Oce analyzed Alabama’s extension of its work

requirement to parents of young children and found

that it increased their employment rate by 11percentage

6. e Urban Institute’s welfare rules database indicates that more

states have tightened work requirements than have loosened

them. See Urban Institute, “Welfare Rules Databook,” https://

wrd.urban.org/wrd/databook.cfm (accessed May 31, 2022).

points.

7

at increase is similar in size to the increase of

10 percentage points that occurred during the rst year

7. Alabama expanded the number of people subject to TANF’s work

requirement when it stopped providing exemptions to parents with

a child between the ages of 6 months and 11 months. In CBO’s

estimation, that expansion increased the employment rate among

participants who were newly subject to the work requirement by

about 4 percentage points in the year following their entry into

TANF. Because the requirement only applied to parents when their

child was between the ages of 6 months and 11 months, though,

participants were newly subject to the work requirement for only

about half of the rst year. Had those participants never been

subject to the work requirement before the expansion and became

subject to it for the full year after the expansion, their employment

rate would have increased by about 9 percentage points in the rst

year after entering the program, CBO estimates. For more details

about the methods CBO used for this analysis, see Appendix B.

Box 2-1 .

How Policy Changes Made to Means-Tested Programs During the 1990s

Aected Single Mothers’ Employment

To encourage employment and limit cash payments, policymak-

ers in the mid-1990s began making changes to the program that

would become Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

Probably the most well-known change was the imposition of work

requirements, which made the receipt of benefits contingent

on working or engaging in work-related activities. Those work

requirements are one of several components of TANF that con-

tributed to the rise in employment among single mothers in the

late 1990s. Other contributing changes include the following:

•

A five-year lifetime limit on TANF’s cash payments.

Researchers have found evidence that the five-year lifetime

limit on cash payments contributed to the rise in employment,

even though no families could have reached that limit by

2000. Those researchers argue that the limit caused some

families to leave TANF for employment earlier so that they

could save some of their potential time in the program in case

of future hardship.

1

•

A weakened disincentive to work. Benefits drop more slowly

as earnings increase under TANF than under its predecessor

program, Aid to Families With Dependent Children. Many

1. Francesca Mazzolari, “Welfare Use When Approaching the Time Limit,”

Journal of Human Resources, vol. 42, no. 3 (Summer 2007),

pp. 596–618, https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.XLII.3.596; and Jerey Grogger,

“The Eects of Time Limits, the EITC, and Other Policy Changes on

Welfare Use, Work, and Income Among Female-Headed Families,” Review

of Economics and Statistics, vol. 85, no. 2 (May 2003), pp. 394–408,

https://doi.org/10.1162/003465303765299891.

states weakened that disincentive to work by reducing

the benefits available to families without earnings and by

allowing families to keep more of their benefits once their

earnings rose.

2

•

Additional funding for work supports. States shifted some

TANF funds from cash payments to work supports, including

subsidized child care and workforce development services.

Policy changes not directly related to TANF also boosted the

employment of single mothers. Of those changes, increases

in the Child Care Development Fund (CCDF) and the earned

income tax credit (EITC) probably contributed the most to their

rise in employment from 1993 to 2000.

3

Lawmakers substantially

increased the EITC in phases from 1994 to 1996, which elevated

the compensation that parents received for working and thus

boosted their incentive to work. Furthermore, lawmakers doubled

spending for the CCDF from 1993 to 2000; the additional sub-

sidized child care provided by that increase made employment

more feasible and profitable for some single mothers.

2. Rebecca M. Blank, “Evaluating Welfare Reform in the United States,” Journal

of Economic Literature, vol. 40, no. 4 (December 2002), pp. 1105–1166,

https://doi.org/10.1257/002205102762203576. That study suggests that the

rapid growth of the economy also contributed to the rise in employment.

3. For a description of the research on the eects of the EITC on the

employment of single mothers, see Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach and

Michael R. Strain, Employment Eects of the Earned Income Tax Credit:

Taking the Long View, Working Paper 28041 (National Bureau of Economic

Research, November 2020), www.nber.org/papers/w28041.

14 WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS JUNE 2022

after parents entered the AFDC waiver experiments.

8

However, the overall size of the increase in employment

was modest because TANF serves far fewer families than

AFDC did.

9

Research on the eects of recent changes to

work requirements made in other states is scant.

Income

Work requirements in TANF have had a small eect on

average income for single mothers. According to studies

from the 1990s, that is because increases in their earn-

ings and in the earned income tax credit roughly equaled

8. See Gayle Hamilton and others, National Evaluation of Welfare-

to-Work Strategies (submitted by Manpower Demonstration

Research Corporation to the Department of Health and Human

Services, December 2001), p. 352, https://tinyurl.com/2p89s5ad.

e employment eects shrank over time. CBO did not

have sucient data to estimate the eect of Alabama’s TANF

expansion over a longer period.

9. In Alabama, TANF served only about 4 percent of single parents

in poverty during an average month in 2018. Nationally, TANF

served about 10 percent of that group, whereas AFDC served

about 77 percent of that group during the years leading up to

enactment of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity

Reconciliation Act.

reductions in cash payments and food assistance.

10

ose

ndings are consistent with trends in the data showing

that the average cash income of single mothers with no

education beyond high school has generally moved in

parallel with the average for their childless counterparts

over the past 30years (see Figure 2-2).

e eect on the income of single mothers has probably

been uneven, though. In recent years, single mothers

who found work while in TANF saw their cash income

rise to an average of about $1,300per month at the

point they left the program, but mothers who left the

program without a job had very little cash income.

11

Income of Former TANF Recipients Who Found Work.

About half of single mothers are employed when they

leave TANF, enabling some of their families to rise out

of poverty. Studies of families that left TANF in the late

10. See Gayle Hamilton and others, National Evaluation of Welfare-

to-Work Strategies (submitted by Manpower Demonstration

Research Corporation to the Department of Health and Human

Services, December 2001), https://tinyurl.com/2p89s5ad.

11. For details on CBO’s analysis, see Appendix B.

Figure 2-2 .

Average Cash Income for Single Women With No Education Beyond High School,

by Presence of Children

Thousands of 2019 Dollars

0

5

10

15

20

25

1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019

With Children

Medicaid

TANF

Without Children

Pretax cash income of

less-educated single

mothers has changed

little, on average, despite

the addition of work

requirements in the 1990s.

Data source: Census Bureau, Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey, from IPUMS-USA. See www.cbo.gov/

publication/57702#data.

The data are by calendar year and are limited to unmarried women between the ages of 18 and 61 who have no postsecondary education, are not students, and

are not receiving disability benefits.

15CHAPTER2: EFFECTS OF WORK REQUIREMENTS ON PEOPLE’S EMPLOYMENT AND INCOME WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS

1990s documented their income in subsequent years.

About half of the families with a working adult had

monthly cash income (in 2019dollars) above $1,716,

which was the poverty threshold for a single parent with

two children in 2019. e primary source of that income

was the parent’s earnings, and some parents had a partner

with substantial earnings as well. Earnings for those fam-

ilies grew modestly in later years, on average.

12

Work requirements have raised the income of employed

single mothers by increasing how quickly they found

a job, which reduced the amount of time they spent

in AFDC/TANF. Between the early stages of welfare

reform in 1993 and PRWORA’s implementation in

1997, the percentage of mothers who had earnings

24months after entering the program rose from about

12. ose ndings come from a summary of studies conducted in

12 states, although data generally were not available for all 12

states. See Gregory Acs and Pamela Loprest, Leaving Welfare:

Employment and Well-Being of Families at Left Welfare in the

Post-Entitlement Era (W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment

Research, 2004), https://doi.org/10.17848/9781417550012.

31percent to about 46percent (see Figure 2-3).

13

at

increase in earnings boosted their income, but some of

the increase was oset by a decline in the cash payments

they received. From 1993 to 1997, the share of families

headed by single mothers who were still receiving cash

payments from AFDC/TANF 24months after entering

the program fell from about 65percent to about 35per-

cent. Over the following years, most single mothers con-

tinued to leave the program within 24months. About

half of those mothers had earnings. For most of them,

the increase in earnings was larger than the reduction in

benets from leaving TANF. In addition, about 25per-

cent of single mothers who had earnings 24months after

entering the program were still receiving cash payments.

Income of Families Without Earnings or Cash

Assistance. About half of single mothers are not

13. Federal law requires states to impose work requirements on

families within their rst 24 months of receiving assistance.

For details, see Appendix A, which compares the changes in

employment and benets for single mothers in SNAP who were

not subject to work requirements.

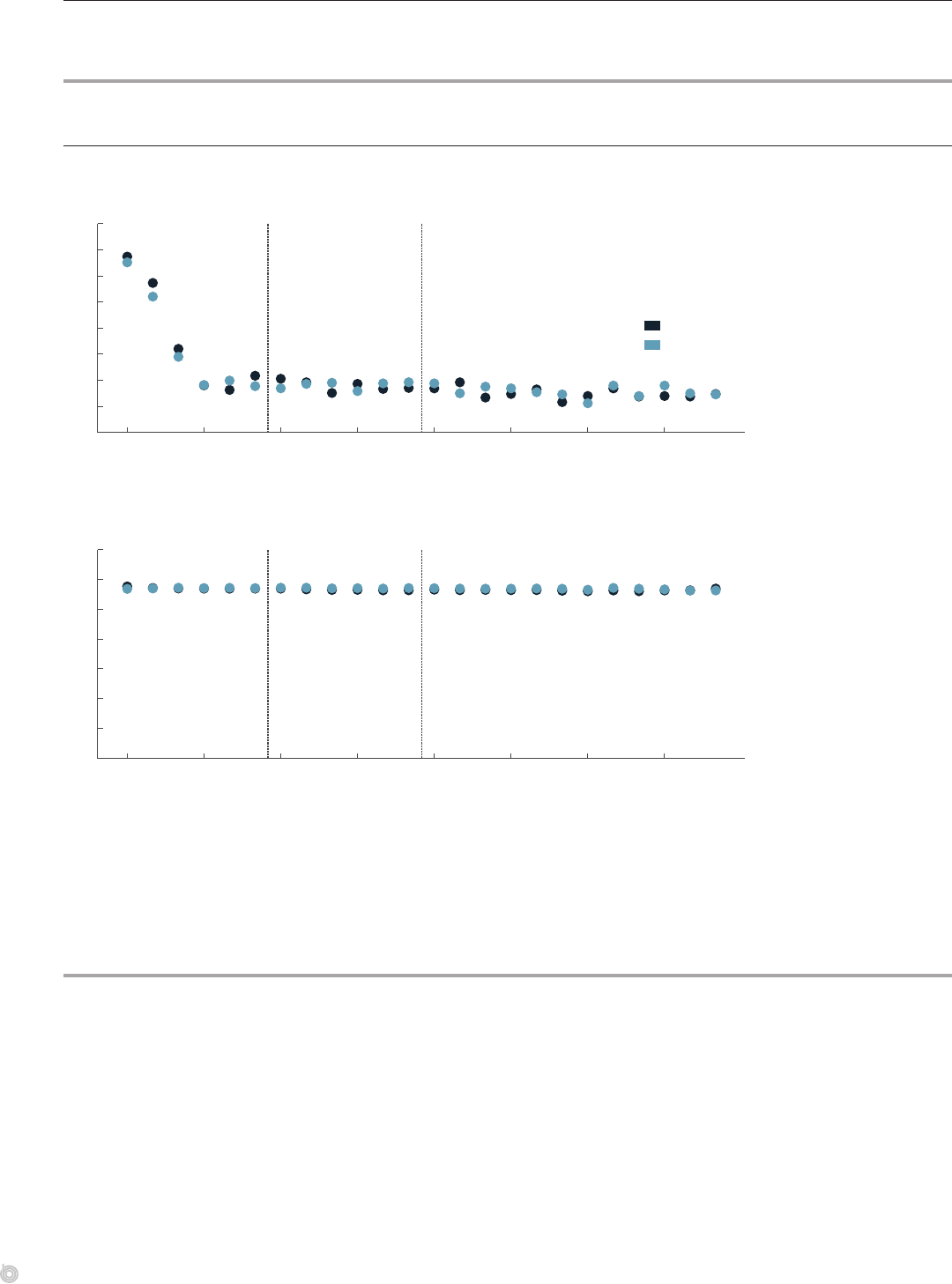

Figure 2-3 .

Sources of Income for Families of Single Women With Children 24 Months After They

Started Receiving Cash Assistance, by Year

Percentage of Families Receiving Income From the Specified Source

0

20

40

60

80

1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019

Employment

AFDC/TANF

After work requirements

were added to cash

assistance programs,

recipients tended to find

employment more quickly

and stop receiving benefits

sooner.

Data source: Survey of Income and Program Participation. See www.cbo.gov/publication/57702#data.

Data are limited to unmarried mothers between the ages of 18 and 61 who received cash assistance from AFDC or TANF, are not students, and are not receiving

disability benefits.

Data are presented only for the years in which the sample size provided sucient precision.

AFDC = Aid to Families With Dependent Children; TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

16 WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS JUNE 2022

employed when they stop receiving cash assistance,

and the share of single mothers without earnings or

cash assistance from AFDC/TANF has risen substan-

tially since welfare reform began.

14

Work requirements

have probably contributed to that increase in two

ways: Families that do not meet those requirements are

removed from TANF, and other families are deterred

from entering the program. However, the low levels of

participation in TANF appear to be primarily driven by

other changes made to AFDC/TANF by PRWORA.

14. One study found that TANF’s work requirements led to some

nonworking single mothers’ receiving more cash assistance

through Supplemental Security Income than they would have

through TANF. e prospect of losing TANF benets because

of the work requirements appears to have led some mothers

to undertake the more strenuous application process for SSI,

which generally provides larger monthly payments than TANF.

See Lucie Schmidt and Purvi Sevak, “AFDC, SSI, and Welfare

Reform Aggressiveness: Caseload Reductions Versus Caseload

Shifting,” Journal of Human Resources, vol. 39, no. 3 (Summer

2004), pp. 792–812, https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.XXXIX.3.792.

Trends in the Data. In the early 1990s, nearly all

less-educated single mothers received recurring cash pay-

ments if they had not worked for an extended period. As

the number of families receiving cash assistance plum-

meted, though, the share of less-educated single mothers

who did not have income from work or AFDC/TANF

rose from close to zero in 1993 to 9percent in 2000,

CBO estimates (see Figure 2-4). Over that period, partic-

ipation in AFDC/TANF declined among those who had

earnings, so the portion of less-educated single moth-

ers who received cash payments fell by about 34per-

centage points in total. In comparison, the portion of

less-educated single mothers who had earnings (whether

they participated in AFDC/TANF or not) increased by

about 14percentage points from 1993 to 2000.

Over the next two decades, the share of less-educated

single mothers who did not have income from work

or TANF continued growing, albeit more gradually.

Reductions in TANF receipt were no longer coun-

tered by substantial increases in employment, leaving

Figure 2-4 .

Sources of Cash Income for Families of Single Women With Children and

With No Education Beyond High School

Percentage of Families

0

20

40

60

80

100

1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019

No Work or

AFDC/TANF

AFDC/TANF

But No Work

Work and

AFDC/TANF

Work But No

AFDC/TANF

The portion of single

mothers without income

from cash assistance or

work rose substantially in

the late 1990s and early

2000s and has stayed

elevated since then.

Data sources: Census Bureau, Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey, from IPUMS-USA; Department of Health and Human

Services. See www.cbo.gov/publication/57702#data.

Data are by calendar year and are limited to unmarried mothers between the ages of 18 and 61 who have no postsecondary education, are not students, and

are not receiving disability benefits. The only sources of income considered are the mother’s employment and recurring cash assistance through TANF or its

predecessor, AFDC. Sources of income have been adjusted for errors in reporting.

AFDC = Aid to Families With Dependent Children; TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

17CHAPTER2: EFFECTS OF WORK REQUIREMENTS ON PEOPLE’S EMPLOYMENT AND INCOME WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS

one-in-seven less-educated single mothers without

income from work or TANF in 2019. (at estimate is

highly uncertain because of imprecision in the underly-

ing data.)

15

Sources of Income. In recent years, most single mothers

without earnings or cash assistance reported being in

deep poverty. ey had little cash income, although they

typically received benets through SNAP to purchase

food. About 39percent of those mothers lived with an

adult who reported working, typically the children’s

(unwed) father. Other mothers reported receiving cash

from people who they did not live with or were not

related to; the most common forms of assistance were

child support (11percent) and help from friends or rel-

atives (11percent). e mothers might understate cash

income from those sources, which could help explain

why single mothers tend to report spending substantially

more income than they report receiving.

16

The Role of Work Requirements. Work requirements

probably increase the number of single mothers with-

out earnings or cash assistance by removing them from

TANF when they are not employed. Work requirements

can aect that number by changing the length of time

nonworking mothers receive assistance and by changing

whether those mothers are employed when they stop

receiving assistance. e expansion of Alabama’s work

requirement in 2018appears to have had little eect on

the latter variable, but it did reduce the length of time

families received assistance by about a month during

the rst year after they entered the program, on average.

us, the work requirement probably caused the number

of families without earnings or cash assistance to increase

modestly. Other research nds evidence of a larger

15. e underreporting of earnings and cash assistance in household

surveys is well established. See Bruce D. Meyer and others,

“e Use and Misuse of Income Data and Extreme Poverty in

the United States,” Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 39, no. S1

(January 2021), pp. S5–S58, https://doi.org/10.1086/711227.

CBO adjusted downward the number of single mothers without

earnings on the basis of inconsistencies between multiple

interviews covering the same years. at adjustment decreased

the estimated number of families without income from work or

AFDC/TANF by 18 percent in 1993; by 2019, the size of that

adjustment had grown to 29 percent. In addition, CBO adjusted

the percentage of single mothers who receive recurring cash

payments so that it matched the administrative data.

16. Bruce D. Meyer and James X. Sullivan, “Changes in the

Consumption, Income, and Well-Being of Single Mother Headed

Families,” American Economic Review, vol. 98, no. 5 (December

2008), https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.5.2221.

increase in the number of such families stemming from

a more stringent work requirement implemented when

the labor market was weaker.

17

In addition, the AFDC

waiver experiments showed that work requirements

often increase the number of families in deep poverty,

and deep poverty is common among families without

earnings or cash assistance.

18

Although some single mothers end up disconnected

from employment and cash payments because they are

removed from TANF for not complying with its work

requirements, most are probably disconnected because

they do not apply for TANF or because their application

is rejected. Before welfare reform, most single mothers

whose income and assets were low enough to qualify for

recurring cash payments received that assistance. But

TANF participation among that group has fallen over

the past three decades, from about 80percent to roughly

25percent.

19

Many single mothers with suciently low

income and assets are not entering the program because

they are ineligible for other reasons or because they do

not complete the application process.

Work requirements may have increased the number of

single mothers without earnings or cash assistance by

stopping some of them from enrolling in TANF. Work

requirements can reduce entry into TANF by discour-

aging parents from applying or by causing them to be

ineligible. e expansion of Alabama’s work requirement

does not appear to have had an immediate eect on

the number of families entering the program. Repeated

violation of the work requirement can lead to families’

being ineligible to enter the program for a year, however.

(Ten other states impose ineligibility periods of a year or

more for repeated violations of the work requirement; six

of those states permanently bar families from reentering

the program.) us, TANF’s work requirements proba-

bly reduce entry into the program by mothers without

earnings by removing them from the program when they

are not working and then barring their reentry. However,

17. Tazra Mitchell, LaDonna Pavetti, and Yixuan Huang, Life After

TANF in Kansas: For Most, Unsteady Work and Earnings Below

Half the Poverty Line (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,

February 2018), https://tinyurl.com/mpxsxkbj.

18. Stephen Freedman and others, National Evaluation of Welfare-

to-Work Strategies (submitted by Manpower Demonstration

Research Corporation to the Department of Health and Human

Services, June 2000), p. 199, https://tinyurl.com/38k9exee.

19. Linda Giannarelli, What Was the TANF Participation Rate in

2016? (Urban Institute, July 2019), https://tinyurl.com/3tny44sc.

18 WORK REQUIREMENTS AND WORK SUPPORTS FOR RECIPIENTS OF MEANSTESTED BENEFITS JUNE 2022

the low levels of participation in TANF appear to be pri-

marily driven by other changes made to AFDC/TANF

by PRWORA.

20

SNAP

e federal government places two work requirements

on adults in SNAP. First, most able-bodied nonelderly

adults who are not working at least 30hours a week or

caring for a child under age 6must register for work—

that is, notify their state’s employment oce that they

are available to work—and accept a suitable job if one