MEDICAID

DEMONSTRATIONS

Actions Needed to

Address Weaknesses

in Oversight of Costs

to Administer Work

Requirements

Report to Congressional Requesters

October 2019

GAO-20-149

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-20-149, a report to

congressional requesters

October 2019

MEDICAID DEMONSTRATIONS

Actions Needed to

Address Weaknesses in

Oversight

of Costs

to Administer Work Requirements

What GAO Found

Medicaid demonstrations enable states to test new approaches to provide

Medicaid coverage and services. Since January 2018, the Centers for Medicare

& Medicaid Services (CMS) has approved nine states’ demonstrations that

require beneficiaries to work or participate in other activities, such as training, in

order to maintain Medicaid eligibility. The first five states that received CMS

approval for work requirements reported a range of administrative activities to

implement these requirements.

These five states provided GAO with estimates of their demonstrations’

administrative costs, which varied, ranging from under $10 million to over $250

million. Factors such as differences in changes to information technology

systems and numbers of beneficiaries subject to the requirements may have

contributed to the variation. The estimates do not include all costs, such as

ongoing costs states expect to incur throughout the demonstration.

Selected States’ Estimates of Administrative Costs to Implement Work Requirements in

Approved Medicaid Demonstrations and Federal Share of those Costs

State

Number of beneficiaries

subject to requirements

Estimated costs

(dollars in millions)

Estimated federal

share (percentage)

Kentucky

620,000

271.6

87

Wisconsin

150,000

69.4

55

Indiana

420,000

35.1

86

Arkansas

115,000

26.1

83

New Hampshire

50,000

6.1

79

Source: GAO analysis of data reported by selected states and selected state documents. | GAO-20-149

Notes: Estimates of beneficiaries subject to work requirements include those who may be eligible for

an exemption. Estimates of costs do not include all costs, and in Kentucky and Wisconsin include

some costs not specific to work requirements. Estimates generally cover from 1 to 3 years of costs.

GAO found weaknesses in CMS’s oversight of the administrative costs of

demonstrations with work requirements.

• No consideration of administrative costs during approval. GAO found

that CMS does not require states to provide projections of administrative

costs when requesting demonstration approval. Thus, the cost of

administering demonstrations, including those with work requirements, is not

transparent to the public or included in CMS’s assessments of whether a

demonstration is budget neutral—that is, that federal spending will be no

higher under the demonstration than it would have been without it.

• Current procedures may be insufficient to ensure that costs are

allowable and matched at the correct rate. GAO found that three of the

five states received CMS approval for federal funds—in one case, tens of

millions of dollars—for administrative costs that did not appear allowable or

at higher matching rates than appeared appropriate per CMS guidance. The

agency has not assessed the sufficiency of its procedures for overseeing

administrative costs since it began approving demonstrations with work

requirements.

View GAO-20-149. For more information,

contact

Carolyn L. Yocom at (202) 512-7114

or

Why GAO Did This Study

Section 1115 demonstrations are a

significant component of Medicaid

spending and affect the care of millions

of low-income and medically needy

individuals. In 2018, CMS announced a

new policy allowing states to test work

requirements under demonstrations

and soon after began approving such

demonstrations. Implementing work

requirements can involve various

administrative activities, not all of

which are eligible for federal funds.

GAO was asked to examine the

administrative costs of demonstrations

with work requirements. Among other

things, this report examines (1) states’

estimates of costs of administering

work requirements in selected states,

and (2) CMS’s oversight of these

costs. GAO examined the costs of

administering work requirements in the

first five states with approved

demonstrations. GAO also reviewed

documentation for these states’

demonstrations, and interviewed state

and federal Medicaid officials.

Additionally, GAO assessed CMS’s

policies and procedures against federal

internal control standards.

What GAO Recommends

GAO makes three recommendations,

including that CMS (1) require states to

submit projections of administrative

costs with demonstration proposals,

and (2) assess risks of providing

federal funds that are not allowable to

administer work requirements and

improve oversight procedures, as

warranted. CMS did not concur with

the recommendations and stated that

its procedures are sufficient given the

level of risk. GAO maintains that the

recommendations are warranted as

discussed in this report.

Page i GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

Letter 1

Background 6

States’ Work Requirements Varied in Terms of Target Population,

Required Activities, and Consequences of Non-Compliance 14

Available Estimates of Costs to Implement Work Requirements

Varied among Selected States, with the Majority of Costs

Expected to Be Financed by Federal Dollars 19

Weaknesses Exist in CMS’s Oversight of Administrative Costs of

Demonstrations with Work Requirements 25

Conclusions 34

Recommendation for Executive Action 34

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 34

Appendix I Other Beneficiary Requirements in States with Approved Medicaid

Work Requirements 38

Appendix II Comments from the Department of Health and Human Services 40

Appendix III GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 44

Related GAO Reports 45

Tables

Table 1: Beneficiary Groups Subject to and Characteristics of

Medicaid Work Requirements in States that Received

Approval for Such Requirements, as of May 2019 15

Table 2: Beneficiary Consequences for Non-Compliance with

Medicaid Work Requirements in States with Approved

Requirements, as of May 2019 17

Table 3: Selected States’ Estimates of Administrative Costs and of

Initial Expenditures for Implementing Medicaid Work

Requirements 20

Table 4: CMS Initiatives that May Provide the Agency with

Information on Demonstration Administrative Costs 27

Contents

Page ii GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

Table 5: Other Beneficiary Requirements in States with Approved

Medicaid Work Requirements, as of May 2019 38

Figures

Figure 1: States with Approved or Pending 1115 Demonstrations

with Work Requirements, as of May 2019 9

Figure 2: Approval and Effective Dates for States with Approved

Work Requirements, as of August 2019 10

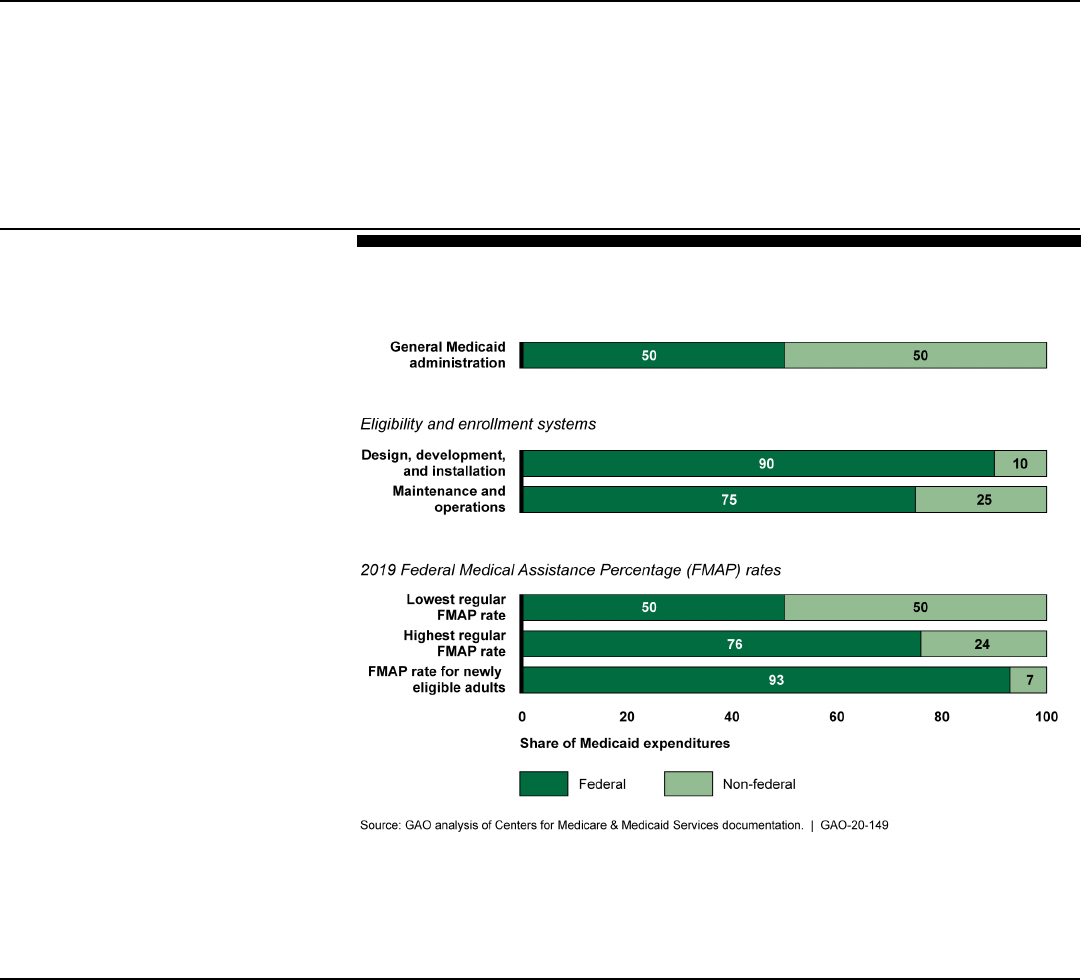

Figure 3: Federal and Non-Federal Shares for Selected Types of

Medicaid Expenditures, Fiscal Year 2019 12

Page iii GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

Abbreviations

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

FMAP Federal Medical Assistance Percentage

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

IT information technology

MCO managed care organization

PPACA Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

SNAP Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program

TANF Temporary Assistance to Needy Families

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

October 1, 2019

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Chairman

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

Medicaid section 1115 demonstrations—which allow states to test and

evaluate new approaches for delivering health care services under the

federal-state Medicaid program—have become a significant feature of the

program.

1

Section 1115 of the Social Security Act authorizes the

Secretary of Health and Human Services to waive certain federal

Medicaid requirements and approve new types of expenditures that would

not otherwise be eligible for federal Medicaid funds for experimental, pilot,

or demonstration projects that, in the Secretary’s judgment, are likely to

promote Medicaid objectives.

2

As of November 2018, over three-quarters

of states operated at least part of their Medicaid program under a section

1115 demonstration; in fiscal year 2017, federal spending for

demonstrations was about $145 billion, or over one-third of federal

Medicaid program expenditures.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), within the

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), oversees Medicaid

section 1115 demonstrations (referred to hereafter as demonstrations)

and has approved states’ use of demonstrations for a variety of purposes.

For example, under demonstrations, states have extended coverage to

populations, offered services not otherwise eligible for Medicaid, and

increased beneficiary premiums and cost-sharing above statutory limits.

1

Medicaid is a joint, federal-state program that finances health care coverage for low-

income and medically needy individuals. The program is a significant component of

federal and state budgets. It covered an estimated 75 million individuals at an estimated

cost of $629 billion in fiscal year 2018, including about $393 billion in federal spending and

$236 billion in state spending, according to estimates from the Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services’ Office of the Actuary.

2

42 U.S.C. § 1315(a).

Letter

Page 2 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

In January 2018, CMS issued guidance announcing a new opportunity for

states to use demonstrations to require certain beneficiaries to work or

participate in community engagement activities, such as vocational

training or volunteer activities, as a condition of Medicaid eligibility.

3

CMS

gave states flexibility in designing the work requirements within certain

parameters. Medicaid beneficiaries not meeting these work requirements

can face suspension or termination of coverage if they do not meet—and

do not appropriately report having met—the number of hours of activity

required. CMS approved the first demonstration testing work

requirements in Kentucky in January 2018 and has since approved such

requirements in eight other state demonstrations, with seven more state

demonstration applications pending as of May 2019. While work

requirements have long been a feature of programs such as Temporary

Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), CMS has not previously approved

work requirements in state Medicaid programs. As of August 2019, there

is ongoing litigation challenging CMS’s approvals of such requirements in

three states that had implemented, or were preparing to implement, work

requirements: Arkansas, Kentucky, and New Hampshire.

4

Implementing work requirements—like other changes in Medicaid—can

increase Medicaid administrative costs, as states may need to change

eligibility and enrollment systems and conduct additional beneficiary

outreach, monitoring, and evaluation.

5

In general, the federal government

3

According to CMS’s guidance, work requirements are to be targeted to non-elderly, non-

pregnant adult Medicaid beneficiaries who are eligible for Medicaid on a basis other than

disability. The guidance indicates that states will be required to provide exemptions for

beneficiaries based on medical frailty, disability, and other reasons. See CMS, State

Medicaid Director Letter; Re: Opportunities to Promote Work and Community Engagement

Among Medicaid Beneficiaries, SMD: 18-002 (Baltimore, Md.: Jan. 11, 2018).

CMS and states have used various terms to refer to these requirements including “work

requirements,” “community engagement requirements,” and “work and community

engagement requirements.” We use the term “work requirements” in this report consistent

with how similar requirements are referenced by other federal programs, including the

Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) and Temporary Assistance to

Needy Families (TANF).

4

The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia vacated CMS’s approvals of the

Arkansas and Kentucky demonstrations with work requirements in March 2019 and CMS’s

approval of New Hampshire’s demonstration in July 2019. Gresham v. Azar, 363 F. Supp.

3d 165 (D.D.C. 2019); Stewart v. Azar, 366 F. Supp. 3d 125 (D.D.C. 2019); Philbrick v.

Azar, No. 19-773 (JEB) (D.D.C. July 29, 2019). As of August 2019, CMS was appealing

the decisions vacating demonstrations in Arkansas and Kentucky.

5

In fiscal year 2018, Medicaid administrative expenditures were estimated to be $28.8

billion or about 4.6 percent of total Medicaid expenditures, according to CMS’s Office of

the Actuary.

Page 3 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

provides 50 percent of the funds for administrative costs, but pays for up

to 90 percent of certain costs, including those for information technology

(IT) system changes. CMS is responsible for overseeing Medicaid

administrative spending and ensuring that federal matching funds are

only provided for costs that are allowable under Medicaid rules.

Stakeholders have raised concerns that work requirements will increase

administrative costs.

Given the number of states opting to test work requirements, you asked

us to examine the administrative costs of demonstrations with work

requirements and CMS oversight of those expenditures. This report

examines

1. characteristics of work requirements in states with approved

demonstrations and pending applications;

2. selected states’ estimates of the administrative costs to implement

demonstrations with work requirements; and

3. CMS’s oversight of the administrative costs of demonstrations with

work requirements.

To examine the characteristics of work requirements in states that have

received approval and those with pending demonstration applications, we

reviewed demonstration documentation from CMS. Specifically, we

reviewed approval documents for the nine states that had received CMS

approval as of May 2019.

6

As part of our review, we identified the extent

of variation across states in the beneficiary groups subject to the work

requirements, including the age and eligibility groups; the hours of work

required and frequency of required reporting; and the consequences for

non-compliance, including both the nature of the consequence—

suspension or termination of coverage—and when it would take effect.

7

We also identified the extent of any variation in the populations states

exempted from the work requirements and the types of activities that met

the requirements. For the seven states with demonstration applications to

6

The nine states that received approval included Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Kentucky,

Michigan, New Hampshire, Ohio, Utah, and Wisconsin. A tenth state, Maine, received

CMS approval for work requirements, but the state subsequently terminated the

demonstration. As such, we did not include Maine in our review.

7

Medicaid eligibility groups include low-income individuals who meet financial and

categorical requirements, such as adults, pregnant women, parents and children,

individuals who are aged, and individuals with disabilities.

Page 4 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

implement work requirements that were pending as of May 2019, we

reviewed application documents for these same characteristics.

To examine selected states’ estimates of the administrative costs of

demonstrations with work requirements, we reviewed state data and

documentation for the five selected states that had received approval as

of November 2018. These states—Arkansas, Indiana, Kentucky, New

Hampshire, and Wisconsin—had the most time to implement work

requirements or make significant preparations to do so during the time

that we conducted our review.

8

Using a data collection instrument

provided to the selected states, we collected available estimates of the

administrative costs for implementing and administering work

requirements over the course of the demonstration approval periods (3 to

5 years), including the states’ estimates of federal and non-federal costs.

9

We also requested available information on the amounts of expenditures

for implementing and administering work requirements incurred from the

date the state submitted its application through the end of calendar year

2018.

10

We asked the selected states to break those expenditures out

according to several types of administrative activities, such as

implementation and operation of IT systems, beneficiary outreach, and

staff training, as well as by expected federal and non-federal amounts.

8

As noted earlier, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia vacated approvals for

Arkansas and Kentucky in March 2019 and the approval for New Hampshire in July 2019.

We included these states in the scope of our review because they had completed

implementation activities prior to the approvals being vacated. Arkansas received approval

of its demonstration in March 2018, implemented work requirements on June 1, 2018, and

administered the requirements for 9 months before the relevant approval was vacated.

Kentucky received approval for its demonstration in January 2018 and initially prepared to

implement work requirements on July 1, 2018. That approval was vacated on June 29,

2018. Kentucky received a new approval for work requirements in November 2018 and

began preparing for implementation in April 2019 before that approval was vacated on

March 27, 2019. New Hampshire received approvals for its demonstration in May and

November 2018, and implemented the demonstration in March 2019 before its approval

was vacated 4 months later.

9

States finance the non-federal share of Medicaid costs in large part through state general

funds and depend on other sources of funds, such as taxes on health care providers and

funds from local governments, to finance the remainder.

10

States sometimes began IT system development activities while their applications were

under review. According to CMS, states can receive federal approval and funds for related

expenditures prior to the approval of the demonstration to the extent CMS determines they

are reasonable and align with required business processes. See, CMS, Medicaid and

CHIP Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) Advanced Planning Documents (APD) for

System Development Associated with 1115 Demonstrations (Baltimore, Md.: June 13,

2019). Selected states submitted applications between August 2016 and July 2018.

Page 5 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

Where states could not provide expenditure amounts for a given type of

activity, we asked them to affirm whether expenditures were incurred for

that activity. We also reviewed related state documentation detailing the

use of the these funds, including descriptions of changes to IT systems

and agreements state Medicaid agencies entered into with managed care

organizations (MCO) or other state agencies to carry out administrative

tasks related to work requirements.

11

In addition, we interviewed Medicaid

officials in the five selected states and asked them about the

administrative activities they had undertaken or planned to take to

implement work requirements, expected ongoing annual costs, and

factors that affected implementation costs. We used our reviews of state

documentation and interviews with officials to identify any inconsistencies

or limitations in the data reported by the states. Based on these steps, we

found the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of our reporting

objectives.

To examine CMS’s oversight of the administrative costs of

demonstrations with work requirements, we reviewed documentation of

policies and procedures for approving, monitoring, and evaluating

demonstrations. This included the policies and procedures applied to all

demonstrations, as well as those applied to demonstrations with work

requirements.

12

We also reviewed policies and procedures for approving

federal funds for changes to Medicaid IT systems. In addition, for our five

selected states, we reviewed state demonstration applications and

interviewed state Medicaid officials about information the states provided

to CMS during the approval process about projected administrative costs.

11

Descriptions of changes to IT systems included proposals submitted by states to CMS

for approval of federal funds at higher federal matching rates available for certain system

development, and maintenance and operations costs, or for updates to previous

approvals, correspondence between the state and CMS on those proposals, and approval

documents.

12

With regard to policies and procedures with general application, we reviewed regulations

detailing state requirements and CMS procedures for transparency of demonstration

approvals and outcomes. 42 C.F.R. pt. 431 subpt. G. We also reviewed CMS’s policy for

ensuring that demonstrations are budget neutral. CMS, State Medicaid Director Letter; Re:

Budget Neutrality Policies for Section 1115(a) Medicaid Demonstration Projects, SMD: 18-

009 (Baltimore, Md.: Aug. 22, 2018). For policies and procedures specific to work and

community engagement requirements, we reviewed guidance to states, issued in January

2018, on applying for approval of work requirements, as well as subsequent guidance,

issued in March 2019, on monitoring and evaluation of demonstrations with work

requirements. CMS, SMD: 18-002; and CMS, 1115 Demonstration State Monitoring &

Evaluation Resources, accessed March 14, 2019,

https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/evaluation-reports/evaluation-

designs-and-reports/index.html.

Page 6 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

We also reviewed state documents detailing plans for obtaining and using

federal funds for the administrative costs associated with work

requirements and related CMS approval documents. We compared

states’ plans with CMS policy on allowable administrative activities—

those eligible for federal Medicaid matching funds—and the appropriate

federal matching rates for those activities. We also interviewed CMS

officials about the extent to which CMS considers administrative costs

when approving demonstrations, how CMS oversees the administrative

costs of demonstrations through the approval of IT funds and other

processes, and how CMS ensures that states receive appropriate federal

matching rates for allowable administrative costs under Medicaid rules.

Finally, we assessed CMS’s policies and procedures against federal

standards for internal controls related to risk assessment.

13

We conducted this performance audit from August 2018 to September

2019 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing

standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to

obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for

our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe

that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings

and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

As of November 2018, 43 states operated at least part of their Medicaid

programs under demonstrations. State demonstrations can vary in size

and scope, and many demonstrations are comprehensive in nature,

affecting multiple aspects of states’ Medicaid programs. In fiscal year

2017, federal spending on demonstrations accounted for more than one-

third of total federal Medicaid spending and in eight states accounted for

75 percent or more of Medicaid expenditures.

CMS typically approves demonstrations for an initial 5-year period that

can be extended in 3- to 5-year increments with CMS approval. Some

states have operated portions of their Medicaid programs under a

13

See GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO-14-704G

(Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014). Internal control is a process affected by an entity’s

oversight body, management, and other personnel that provides reasonable assurance

that the objectives of an entity will be achieved.

Background

Medicaid Section 1115

Demonstrations

Page 7 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

demonstration for decades. Each demonstration is governed by special

terms and conditions, which reflect the agreement reached between CMS

and the state, and describe the authorities granted to the state. For

example, the special terms and conditions may define what

demonstration funds can be spent on—including which populations and

services—as well as specify reporting requirements, such as monitoring

or evaluation reports states must submit to CMS.

In January 2018, CMS announced a new policy to support states

interested in using demonstrations to make participation in work or

community engagement a requirement to maintain Medicaid eligibility or

coverage.

14

CMS’s guidance indicates that states have flexibility in

designing demonstrations that test work requirements, but it also

describes parameters around the populations that could be subject to

work requirements and other expectations. CMS guidance addresses

several areas, including the following:

• Populations. Work requirements should apply to working-age, non-

pregnant adult beneficiaries who qualify for Medicaid on a basis other

than a disability.

• Exemptions and qualifying activities. States must create

exemptions for individuals who are medically frail or have acute

medical conditions. States must also take steps to ensure eligible

individuals with opioid addiction and other substance use disorders

have access to coverage and treatment services and provide

reasonable modifications for them, such as counting time spent in

medical treatment toward work requirements. The guidance indicates

that states can allow a range of qualifying activities that satisfy work

requirements, such as job training, education programs, and

community service. The guidance also encourages states to consider

aligning Medicaid work requirements with work requirements in other

federal assistance programs operating in their states.

15

14

See CMS, SMD: 18-002.

15

For example, SNAP includes work requirements that certain adult participants must

comply with as a condition of eligibility for benefits. However, certain participants are

exempt from SNAP work requirements, such as those who are physically unfit for

employment or those participating in a drug addiction or alcohol treatment and

rehabilitation program.

Work Requirements

Page 8 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

• Beneficiary supports. States are expected to describe their

strategies to assist beneficiaries in meeting work requirements and to

link them to additional resources for job training, child care assistance,

transportation, or other work supports. However, CMS’s guidance

specifies that states are not authorized to use Medicaid funds to

finance these beneficiary supports.

About one-third of states have either received CMS approval or submitted

applications to CMS to test work requirements in their demonstrations.

Nine states have had work requirements approved as part of new

demonstrations or extensions of or amendments to existing

demonstrations as of May 2019.

16

Also as of May 2019, seven more

states had submitted demonstration applications with work requirements,

which were pending CMS approval. (See fig. 1.)

16

CMS also approved a demonstration for Maine to institute work requirements in

December 2018, with implementation scheduled for July 2019. However, in January 2019,

Maine communicated to CMS that the state would not be implementing the demonstration.

Page 9 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

Figure 1: States with Approved or Pending 1115 Demonstrations with Work Requirements, as of May 2019

a

A federal district court vacated CMS’s approvals of demonstrations in Arkansas and Kentucky in

March 2019, and in New Hampshire in July 2019; as of August 2019, CMS was appealing the

decisions vacating demonstrations in Arkansas and Kentucky. CMS approved a demonstration for

Maine to institute work requirements in December 2018. However, in January 2019, Maine

communicated to CMS that the state would not be implementing the demonstration, and, as a result,

we listed Maine as having no pending or approved application.

Page 10 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

States with approved work requirements were in various stages of

implementation as of August 2019, and three states faced legal

challenges to implementation. The requirements were in effect in

Arkansas for 9 months before a federal district court vacated the approval

in March 2019.

17

Work requirements became effective in Indiana in

January 2019 and will be enforced beginning in January 2020. CMS’s

approval of work requirements in Kentucky was vacated in March 2019—

several days before the work requirements were set to become effective

on April 1, 2019.

18

As of August 2019, CMS was appealing the court

decisions vacating demonstration approvals in Arkansas and Kentucky.

Other states’ requirements are approved to take effect in fiscal years

2020 and 2021. (See fig. 2.)

Figure 2: Approval and Effective Dates for States with Approved Work Requirements, as of August 2019

17

Gresham v. Azar, 363 F. Supp. 3d 165 (D.D.C. 2019).

18

CMS’s initial approval of Kentucky’s demonstration in January 2018 was vacated by the

U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in June 2018. Stewart v. Azar, 313 F. Supp.

3d 237 (D.D.C. 2018). CMS reapproved Kentucky’s demonstration on November 20,

2018. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia vacated this approval on March

27, 2019. Stewart v. Azar, 366 F. Supp. 3d 125 (D.D.C. 2019).

Page 11 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

Notes: Kentucky was first approved to implement work requirements in January 2018; this approval

was vacated by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in June 2018. CMS reapproved

Kentucky’s demonstration in November 2018. New Hampshire was first approved in May 2018 to

implement work requirements, and, in November 2018, CMS approved an extension of the state’s

demonstration, including its work requirements. Under the terms of the approvals, states have

discretion to delay effective dates for work requirements.

Implementing work requirements, as with other types of beneficiary

requirements, can involve an array of administrative activities by states,

including developing or adapting eligibility and enrollment systems,

educating beneficiaries, and training staff. In general, CMS provides

federal funds for 50 percent (referred to as a 50 percent matching rate) of

state Medicaid administrative costs. These funds are for activities

considered necessary for the proper and efficient administration of a

state’s Medicaid program, including those parts operated under

demonstrations.

19

CMS provides higher matching rates for certain

administrative costs, including those related to IT systems. For example,

expenditures to design, develop, and install Medicaid eligibility and

enrollment systems are matched at 90 percent, and maintenance and

operations of these systems are matched at 75 percent.

20

States may also receive federal funds for administrative activities

delegated to MCOs. The amount of federal Medicaid funds states receive

for payments to MCOs that bear financial risk for Medicaid expenditures

is determined annually by a statutory formula based on the state’s per

capita income, known as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage

(FMAP).

21

The FMAP sets a specific federal matching rate for each state

that, for fiscal year 2019, ranges from 50 percent to 76 percent. There are

exceptions to this rate for certain populations, providers, and services.

For example, states that chose to expand Medicaid under the Patient

Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) receive a higher FMAP for

newly eligible adults, equal to 93 percent in 2019.

22

(See fig. 3.)

19

42 U.S.C. § 1396b(a)(7).

20

42 U.S.C. § 1396b(a)(3)(A)(i), (a)(3)(B).

21

42 U.S.C. § 1396d(b). The FMAP applies broadly to Medicaid expenditures, including

expenditures for most Medicaid services.

22

Newly eligible adults under PPACA include nonelderly, nonpregnant adults who are not

eligible for Medicare, and whose income does not exceed 138 percent of the federal

poverty level. The FMAP for newly eligible adults will decrease to 90 percent in 2020.

Federal Funding for

Administrative Costs to

Implement Work

Requirements

Page 12 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

Figure 3: Federal and Non-Federal Shares for Selected Types of Medicaid

Expenditures, Fiscal Year 2019

Notes: The FMAP is a statutory formula that determines the federal government’s share for most

Medicaid expenditures based on each state’s per capita income relative to the national average. In

2019, the federal share ranged from 50 percent to 76 percent. Newly eligible adults refer to

individuals eligible because their state chose to expand Medicaid under the Patient Protection and

Affordable Care Act. Under the act, costs for these individuals are matched at a higher rate than the

regular FMAP rates.

CMS has several different related processes under which the agency

oversees Medicaid administrative costs, including those for

demonstrations.

• Demonstration approval, monitoring, and evaluation. States

seeking demonstration approvals must meet transparency

requirements established by CMS. For example, states must include

certain information about the expected changes in expenditures under

the demonstration in public notices seeking comment at the state level

and in the application to CMS, which is posted for public comment at

the federal level. In addition, CMS policy requires that demonstrations

be budget neutral—that is, that the federal government should spend

no more under a demonstration than it would have without the

demonstration. Prior to approval, states are required to submit an

CMS Oversight of

Administrative Costs

Page 13 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

analysis of their projected costs with and without the demonstration.

CMS uses this information to determine budget neutrality and set

spending limits for demonstrations. During the demonstration, CMS is

responsible for monitoring the state’s compliance with the terms and

conditions of the demonstration, including those related to how

Medicaid funds can be spent and the demonstration spending limit.

States must also evaluate their demonstrations to assess the effects

of the policies being tested, which could include impacts on cost.

• Review and approval of federal matching funds for IT projects.

To request higher federal matching rates for changes to Medicaid IT

systems, including eligibility and enrollment systems, states must

submit planning documents to CMS for review and approval. States’

plans must include sufficient information to evaluate the state’s goals,

procurement approach, and cost allocations within a specified budget.

States may request funds for system development related to a

proposed demonstration before the demonstration is approved.

Funding can be approved and expended under the approved plan

while the demonstration application is being reviewed.

23

States submit

updates to planning documents annually for CMS review, which can

include requested changes to the approved budget.

• Quarterly expenditure reviews. In order to receive federal matching

funds, states report their Medicaid expenditures quarterly to CMS,

including those made under demonstrations. Expenditures associated

with demonstrations, including administrative expenditures, are

reported separately from other expenditures. CMS is responsible for

ensuring that expenditures reported by states are supported and

allowable, meaning that the state actually made and recorded the

expenditure and that the expenditure is consistent with Medicaid

requirements. With regard to consistency, this includes comparing

reported expenditures to various approval documents. For example,

CMS is responsible for comparing reported demonstration

expenditures against the special terms and conditions that authorize

payment for specified services or populations and establish spending

limits. CMS is also responsible for reviewing states’ reported

expenditures against budgets in states’ planning documents to ensure

that states do not exceed approved amounts.

A list of GAO reports related to these CMS oversight processes is

included at the end of this report.

23

CMS’s process recognizes that for timely implementation, some system design,

development, and installation may need to occur prior to demonstration approval.

Page 14 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

States took different approaches to designing work requirements under

their Medicaid demonstrations. These requirements varied in terms of the

beneficiary groups subject to the requirements; the required activities,

such as frequency of required reporting; and the consequences

beneficiaries face if they do not meet requirements.

In the nine states with approved work requirements as of May 2019, we

found differences in the age and eligibility groups subject to work

requirements, and, to a lesser extent, the number of hours of work

required and frequency of required reporting to the state. For example:

• Age and eligibility groups subject to work requirements. Four of

these states received approval to apply the requirements to adults

under the age of 50, similar to how certain work requirements are

applied under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP).

24

Among the other five states, approved work requirements

apply to adults up to the age of 59 (Indiana and Utah), 62 (Michigan),

and 64 (Kentucky and New Hampshire). States generally planned to

apply the requirements to adults newly eligible under PPACA or a

previous coverage expansion, but some states received approval to

apply the requirements to additional eligibility groups, such as parents

and caretakers of dependents.

25

• Number of hours of work required and frequency of required

reporting. Under approved demonstrations in seven states, Medicaid

beneficiaries must complete 80 hours of work or other qualifying

24

Generally, SNAP recipients ages 18 through 49 who are not physically or mentally unfit

for employment, are in a household not responsible for a dependent child, and do not

meet other exemptions must work or participate in a work program 20 hours or more per

week or otherwise earn the value of their SNAP benefits. In addition, SNAP recipients

ages 16 through 59 must generally comply with general work requirements that typically

include registering for work and may include additional required activities.

25

Prior to PPACA, states could expand coverage to populations not traditionally eligible for

Medicaid—such as childless adults—using state funds or through a section 1115

demonstration.

States’ Work

Requirements Varied

in Terms of Target

Population, Required

Activities, and

Consequences of

Non-Compliance

Beneficiaries Subject to

Work Requirements and

Required Activities

Page 15 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

activities per month to comply with work requirements. Five states’

approved demonstrations require beneficiaries to report each month

on their hours of work or other qualifying activities, using methods

approved by the state, such as online or over the phone. (See table

1.)

We saw similar variation under the seven state applications that were

pending as of May 2019.

26

Table 1: Beneficiary Groups Subject to and Characteristics of Medicaid Work Requirements in States that Received Approval

for Such Requirements, as of May 2019

Beneficiary groups subject to the work requirements

Beneficiary reporting requirements

State

Maximum age

Newly eligible

adults

a

Other eligibility

groups

b

Number of

hours required

monthly

Frequency of

required

reporting to state

Arizona

49

✓

—

80

Monthly

Arkansas

49

✓

—

80

Monthly

Indiana

59

✓

✓

80

Annually

Kentucky

64

✓

✓

80

Monthly

Michigan

62

✓

—

80

Monthly

New Hampshire

64

✓

—

100

Monthly

Ohio

49

✓

—

80

Annually

Utah

59

c

✓

d

Annually

Wisconsin

49

c

—

80

e

Legend:

✓ = yes

— = not applicable

Source: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) documentation. | GAO-20-149

Note: The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia vacated CMS’s approvals of demonstrations

in Arkansas and Kentucky in March 2019, and in New Hampshire in July 2019. Gresham v. Azar, 363

F. Supp. 3d 165 (D.D.C. 2019); Stewart v. Azar, 366 F. Supp. 3d 125 (D.D.C. 2019); Philbrick v. Azar,

No. 19-773 (JEB) (D.D.C. July 29, 2019).

a

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) permitted states to expand Medicaid

coverage to nonelderly, non-pregnant adults who are not eligible for Medicare and whose income

does not exceed 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

b

This includes such groups as parents and caretakers of dependents.

26

States’ pending applications varied in terms of the age groups subject to the

requirements with maximum ages ranging from 50 years to 65 years. In terms of eligibility

groups, six of the seven states had not expanded Medicaid to those newly eligible under

PPACA. Thus, those states’ applications focused the work requirements on other eligibility

groups, such as parents and caretakers of dependents. All seven states were seeking

approval to require beneficiaries to complete 80 hours per month (or 20 hours per week)

of work or other qualifying activities, and one state planned to require childless adults to

participate 30 hours per week.

Page 16 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

c

Utah and Wisconsin expanded coverage to adults with incomes at or below 100 percent—rather than

138 percent—of the federal poverty level and gained approval to subject those beneficiaries to work

requirements.

d

Utah requires beneficiaries to work 30 hours per week or complete a set of qualifying activities.

e

Wisconsin’s approval to implement work requirements does not specify the frequency of required

reporting.

All nine states with approved work requirements as of May 2019

exempted several categories of beneficiaries and counted a variety of

activities as meeting the work requirements. For example, all nine states

exempted from the work requirements people with disabilities, pregnant

women, and those with certain health conditions, such as a serious

mental illness.

27

In addition, depending on the state, other groups were

also exempted, such as beneficiaries who are homeless, survivors of

domestic violence, and those enrolled in substance use treatment

programs. States also counted activities other than work as meeting the

work requirements, such as job training, volunteering, and caregiving for

non-dependents. In addition to work requirements, eight of the nine states

received approval under their demonstrations to implement other

beneficiary requirements, such as requiring beneficiaries to have

expenditure accounts.

28

(See app. I for more information on these other

beneficiary requirements.)

The consequences Medicaid beneficiaries faced for non-compliance and

the timing of the consequences varied across the nine states with

approved work requirements. The consequences for non-compliance

included coverage suspension and termination.

29

For example, Arizona

received approval to suspend beneficiaries’ coverage after 1 month of

non-compliance. In contrast, Wisconsin will not take action until a

beneficiary has been out of compliance for 4 years, at which time

27

CMS guidance requires states to exempt certain populations, such as individuals

determined to be medically frail and individuals classified as “disabled” for Medicaid

eligibility purposes, and to make reasonable modifications for others.

28

Beneficiary expenditure accounts are similar to health savings accounts where funds are

used to pay for health care expenses.

29

Under a suspension, beneficiaries remain enrolled, but coverage is suspended until they

come into compliance with the work requirements or a specified period of time has

elapsed. Under termination, enrollment in the Medicaid program is terminated for

individuals and they must reapply to regain coverage. In some states, coverage may first

be suspended and subsequently terminated if beneficiaries do not come into compliance

by their annual eligibility redetermination.

Beneficiary Consequences

for Non-Compliance

Page 17 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

coverage will be terminated. Three states (Arkansas, Michigan, and

Wisconsin) imposed or planned to impose a non-eligibility period after

terminating a beneficiary’s enrollment.

30

For example, under Arkansas’

demonstration, after 3 months of non-compliance, the beneficiary was not

eligible to re-enroll until the next plan year, which began in January of

each year. Thus, beneficiaries could be locked out of coverage for up to 9

months. (See table 2.) For states with pending applications, suspension

or termination of coverage takes effect after 2 or 3 months of non-

compliance.

Table 2: Beneficiary Consequences for Non-Compliance with Medicaid Work Requirements in States with Approved

Requirements, as of May 2019

State

Number of months of non-

compliance before consequence Type of consequence

a

Non-eligibility period

b

Arizona

1

Suspension

—

Arkansas

3 in a calendar year

Termination

0 to 9 months

Indiana

4 in a calendar year

Suspension then termination

—

Kentucky

2 in a row

Suspension then termination

—

Michigan

3 in 12 months

Termination

At least 1 month

New Hampshire

2 in a row

Suspension then termination

—

Ohio

2 (60 days)

Termination

—

Utah

3 in 12 months

Termination

—

Wisconsin

48

Termination

6 months

Legend:

— = not applicable

Source: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) documentation. | GAO-20-149

Note: The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia vacated CMS’s approvals of demonstrations

in Arkansas and Kentucky in March 2019, and in New Hampshire in July 2019. Gresham v. Azar, 363

F. Supp. 3d 165 (D.D.C. 2019); Stewart v. Azar, 366 F. Supp. 3d 125 (D.D.C. 2019); Philbrick v. Azar,

No. 19-773 (JEB) (D.D.C. July 29, 2019).

a

Under a suspension, beneficiaries remain enrolled, but coverage is suspended until they come into

compliance with the work requirements or a specified period of time has elapsed. Under termination,

enrollment in the Medicaid program is terminated for individuals and they must reapply to regain

coverage. In some states, coverage may first be suspended and subsequently terminated if

beneficiaries do not come into compliance by their annual eligibility redetermination.

b

States with a non-eligibility period restrict an individual from reenrolling in the program following a

coverage termination due to noncompliance with the work requirements for a set period of time or

until certain conditions are met.

30

States with a non-eligibility period restrict an individual from reenrolling in the program

following a coverage termination due to noncompliance with the work requirements for a

set period of time or until certain conditions are met.

Page 18 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

For states that suspend coverage for beneficiaries, there are different

conditions for coming into compliance and lifting the suspension. For

example:

• Arizona received approval to automatically reactivate an individual’s

eligibility at the end of each 2-month suspension period.

• In other states, such as Indiana, beneficiaries must notify the state

that they have completed 80 hours of work or other qualifying

activities in a calendar month, after which the state will reactivate

eligibility beginning the following month. (See text box.)

Indiana’s Suspension Process for Non-Compliance with Medicaid Work

Requirements

At the end of each year, the state reviews beneficiaries’ activities related to work

requirements. Beneficiaries must meet the required monthly hours 8 out of 12 months of

the year to avoid a suspension of Medicaid coverage.

If coverage is suspended for not meeting work requirements, the suspension will start

January 1 and could last up to 12 months. During a suspension, beneficiaries will not be

able to access Medicaid coverage to receive health care.

Beneficiaries with suspended Medicaid coverage can reactivate coverage if they become

• pregnant;

• medically frail; or

• employed, enrolled in school, or engaged in volunteering.

Beneficiaries must contact the state to reactivate coverage.

Source: GAO summary of Indiana’s “Gateway to Work suspension process” website, accessed June 24, 2019,

https://www.in.gov/fssa/hip/2593.htm. | GAO-20-149.

To prevent suspension from taking effect, two states (Kentucky and New

Hampshire) require beneficiaries to make up required work hours that

were not completed in order to maintain compliance with work

requirements. For example, in Kentucky, if the beneficiary worked 60

hours in October (20 hours less than the required 80), the beneficiary

Page 19 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

must work 100 hours in November to avoid suspension of coverage in

December.

31

Available estimates of the costs to implement Medicaid work

requirements varied considerably among the five selected states, and

these estimates did not account for all costs. These states estimated that

federal funding would cover the majority of these costs, particularly costs

to modify IT systems.

Selected states (Arkansas, Indiana, Kentucky, New Hampshire, and

Wisconsin) reported estimates of the costs to implement work

requirements that ranged from under $10 million in New Hampshire to

over $250 million in Kentucky.

32

These estimates—compiled by states

and reported to us—did not include all planned costs. The estimates were

based on information the states had readily available, such as the costs

of contracted activities for IT systems and beneficiary outreach, and

primarily reflect up-front costs. Four selected states (Arkansas, Indiana,

Kentucky, and New Hampshire) had begun implementing work

requirements and making expenditures by the end of 2018. Together,

these states reported to us having spent more than $129 million in total

31

Kentucky’s vacated approval also allowed beneficiaries to avoid suspension or have

their coverage reactivated if they become suspended if they complete a state-approved

health or financial literacy course—an option that could be used once in a 12-month

period.

32

We collected information from the five states that received approval for demonstrations

with work requirements as of November 2018, which had the most time to implement work

requirements or make significant preparations to do so during the time that we conducted

our review. Kentucky’s and Wisconsin’s estimates include some costs not specific to work

requirements.

Available Estimates of

Costs to Implement

Work Requirements

Varied among

Selected States, with

the Majority of Costs

Expected to Be

Financed by Federal

Dollars

Selected States’ Estimates

of Administrative Costs

Associated with Work

Requirements Ranged

from Millions to Hundreds

of Millions of Dollars

Page 20 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

for implementation activities from the time the states submitted their

demonstration applications through the end of 2018.

33

(See table 3.)

Table 3: Selected States’ Estimates of Administrative Costs and of Initial Expenditures for Implementing Medicaid Work

Requirements

State

Estimated

costs

(dollars in

millions)

Description of estimates of administrative costs and of initial expenditures

Kentucky

271.6

•

Estimate includes $220.9 million in information technology (IT) costs for the Medicaid

demonstration as a whole, including work requirements, for fiscal years 2019 and 2020, and

$50.7 million in payments for managed care organizations’ cost to administer work and other

beneficiary requirements for the period of July 2018 through June 2020.

• Estimate does not include expected costs for evaluating work requirements.

Expenditures from application date (August 2016) through 2018: more than $99.5 million.

a

Wisconsin

69.4

•

Estimate includes $57.3 million for beneficiary outreach, evaluation, and other services from July

2019 through June 2021, and $12.1 million in fiscal year 2019 for IT systems changes for the

Medicaid demonstration as a whole.

Expenditures from application date (January 2018) through 2018: None.

b

Indiana

35.1

•

Estimate includes $14.4 million for IT systems for fiscal years 2018 through 2021, and $20.7

million for managed care organizations’ activities in 2019.

• Estimate does not include expected costs for evaluation.

Expenditures from application date (July 2017) through 2018: more than $800,000.

c

Arkansas

26.1

•

Estimate includes contracts in place from July 2017 through June 2019 for IT systems,

beneficiary outreach, and other activities, such as data analysis.

• Estimate does not include expected costs for beneficiary notices and increased payments to

qualified health plans.

Expenditures from application date (June 2017) through 2018: more than $24.1 million.

d

New

Hampshire

6.1

•

Estimate includes $4.5 million for IT system and other contracts in place from July 2018 through

June 2019, and $1.6 million for evaluation activities from 2019 through 2025.

• Estimate does not include all expected costs, such as increased payments to managed care

organizations.

Expenditures from application date (October 2017) through 2018: more than $4.4 million.

e

Source: GAO analysis of data reported by selected states and selected state documents. | GAO-20-149

Notes: States used standardized data collection instruments to report to GAO their estimated costs

and expenditures to implement work requirements approved under Medicaid section 1115

demonstrations.

a

Kentucky’s expenditures include costs associated with the demonstration as a whole, such as project

management and training costs. These costs do not include payments to managed care

organizations.

33

As with estimated costs, states’ expenditure amounts represented available information

and did not include all expenditures associated with implementing Medicaid work

requirements.

Page 21 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

b

Wisconsin had not begun to implement work requirements by the end of 2018 and so had not made

associated expenditures.

c

Indiana did not include expenditures they could not separately identify, such as expenditures

associated with beneficiary outreach, staff training, demonstration evaluation, and other activities.

d

Arkansas did not include expenditures they could not separately identify, such as expenditures

associated with notices, staff training, qualified health plans’ activities to educate beneficiaries, and

other activities. Arkansas included all expenditures for one contract that expired in March 2019.

e

New Hampshire did not include expenditures they could not separately identify, such as certain

beneficiary outreach expenditures.

Several factors may have contributed to the variation in the selected

states’ estimated costs of administering work requirements, including

planned IT system changes and the number of Medicaid beneficiaries

subject to the work requirements.

IT system changes. Selected states planned distinct approaches to

modify their IT systems in order to administer work requirements. For

example:

• Indiana, which implemented work requirements by expanding on an

existing work referral program, planned to leverage existing IT

systems, making modifications expected to result in IT costs of $14.4

million over 4 years.

• In contrast, Kentucky planned to develop new IT system capabilities

to communicate, track, and verify information related to work

requirements. Kentucky received approval to spend $220.9 million in

fiscal years 2019 and 2020 to do that and make changes needed to

implement other beneficiary requirements in its demonstration.

Number of beneficiaries subject to requirements. The estimated cost

of some activities to administer work requirements depended on the

number of Medicaid beneficiaries subject to work requirements, which

varied across selected states. For example:

• Kentucky estimated 620,000 beneficiaries would be subject to work

requirements—including those who may qualify for exemptions—and

estimated costs of $15 million for fiscal years 2019 and 2020 to

conduct beneficiary education, outreach, and customer service.

• In contrast, Arkansas had fewer beneficiaries subject to work

requirements (about 115,000 in February 2019, with about 100,000 of

those eligible for exemptions) and estimated fewer outreach costs.

Page 22 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

The state estimated $2.9 million in costs from July 2018 through June

2019 to conduct education and outreach.

34

As noted earlier, states’ available estimates did not include all expected

Medicaid costs. For example, four of the five selected states planned to

use MCOs or other health plans to help administer work requirements,

but two of these four did not have estimates of the associated costs.

Indiana and Kentucky estimated additional payments to MCOs—$20.7

million in Indiana to administer work requirements in 2019 and $50.7

million in Kentucky to administer its demonstration from July 2018 through

June 2020. In contrast, officials in New Hampshire told us that no

estimates were available. In Arkansas, where beneficiaries receive

premium support to purchase coverage from qualified health plans on the

state’s health insurance exchange, plans were instructed to include the

costs of administering work requirements in the premiums, according to

Arkansas officials. State officials and representatives from a qualified

health plan we spoke with could not provide the amount that the state’s

premium assistance costs increased as a result.

States’ estimates also did not include all ongoing costs that they expect to

incur after the up-front costs and initial expenditures related to

implementation of the work requirements. States had limited information

about ongoing costs, but we collected some examples. For instance, New

Hampshire provided estimated costs of $1.6 million to design and

implement the evaluation of its demonstration, which all states are

required to perform. In addition, officials or documents in each selected

state acknowledged new staffing costs that may be ongoing, such as

Indiana’s costs for five full-time employees to assist beneficiaries with

suspended coverage to meet requirements or obtain exemptions.

35

Finally, states reported that administering Medicaid work requirements

will increase certain non-Medicaid costs—costs that are not funded by

federal Medicaid, but are borne by other federal and state agencies,

stakeholders, or individuals. For instance, New Hampshire officials

34

Other selected states’ estimates of the number of beneficiaries potentially subject to the

requirements (including those who may qualify for exemptions) were as follows: 420,000

in Indiana; 50,000 in New Hampshire; and 150,000 in Wisconsin, although this included

beneficiaries aged 50 and up who are not subject to work requirements.

35

Another example of new staffing costs that may be ongoing is Kentucky’s estimate of

MCOs’ annual costs of $5.4 million for 270 caseworkers to help identify beneficiaries with

certain medical frailties. These beneficiaries receive 12-month exemptions from work

requirements, mandatory cost sharing, and healthy behavior incentives.

Page 23 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

planned to use approximately $200,000 to $300,000 in non-Medicaid

funds for six positions performing case management for workforce

development. Similarly, in July 2017, Indiana estimated that providing

beneficiaries with job skills training, job search assistance, and other

services would cost $90 per month per beneficiary, although state officials

said these costs were uncertain after learning they were not eligible for

federal Medicaid funds. In addition, beneficiaries and entities other than

states, such as community organizations, may incur costs related to the

administration of work requirements that are not included in states’

estimates.

36

All five selected states expected to receive federal funds for the majority

of estimated costs and expenditures (described previously) for

implementing work requirements.

37

For example, the four selected states

that provided data on expenditures to administer work requirements

through 2018 (Arkansas, Indiana, Kentucky, and New Hampshire)

expected the portion of those expenditures paid by the federal

government to range from 82 percent in Indiana to 90 percent in New

Hampshire and Kentucky.

38

These effective matching rates exceed the 50

percent matching rate for general administrative costs, largely due to

higher matching rates of 75 and 90 percent of applicable IT costs. For

example, Kentucky received approval to spend $192.6 million in federal

funds for its $220.9 million in expected IT costs over 2 years to implement

work requirements and other beneficiary requirements, an effective match

rate of 87 percent.

In addition to higher federal matching rates for IT costs, the selected

states receive federal funds for the majority of MCO capitation payments,

which the states planned to increase to pay MCOs’ costs to administer

36

For example, according to representatives of a stakeholder organization we interviewed,

churches, libraries, and homeless services organizations in Arkansas have dedicated

resources to help beneficiaries comply with work requirements, and beneficiaries spent

time and resources for transportation costs and cellular phone minutes to comply with

work requirements. In addition, we spoke with representatives of a qualified health plan in

Arkansas that serves Medicaid beneficiaries who said that administering work

requirements would increase non-Medicaid members’ premiums.

37

States reported that the federal share of estimated costs would be as follows: Arkansas,

83 percent; Indiana, 86 percent; Kentucky, 87 percent; New Hampshire, 79 percent; and

Wisconsin, 55 percent.

38

The federal share of expenditures reported by Arkansas was 86 percent.

Selected States Estimated

the Federal Government

Would Pay the Majority of

Administrative Costs

Associated with Work

Requirements

Page 24 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

work requirements.

39

Each of the three states that planned to use MCOs

to administer work requirements planned to increase capitation payments

in order to do so. For example, Indiana planned to increase capitation

payments to MCOs by approximately 1 percent (or $20.7 million in 2019)

to pay for a variety of ongoing activities to administer work requirements,

including requiring MCOs to help beneficiaries report compliance,

reporting beneficiaries who qualify for exemptions, and helping the state

verify the accuracy of beneficiary reporting, according to state officials.

The federal government pays at least 90 percent of capitation payments

to MCOs to provide covered services to beneficiaries who are newly

eligible under PPACA, the primary population subject to work

requirements among the five selected states.

40

Indiana and Kentucky also

received approval to apply work requirements to other populations, and

capitation payments for these other populations receive federal matching

rates of 66 percent in Indiana and 72 percent in Kentucky in fiscal year

2019.

States’ approaches to implementing work requirements can affect the

federal matching funds they receive. For example, Arkansas officials told

us that the state decided to collect information on beneficiary compliance

through an on-line portal—the initial cost of which received an effective

federal matching rate of 87 percent, according to Arkansas. Officials told

us that the state avoided having beneficiaries report compliance to staff—

costs of which receive a 75 percent matching rate.

41

However, after

approximately 17,000 beneficiaries lost coverage due to non-compliance

with work requirements, Arkansas revised its procedures to allow

beneficiaries to report compliance to state staff over the phone.

Three of the five selected states sought to leverage other programs

funded by the federal government to help implement work requirements

39

Capitation payments provide MCOs a set payment per beneficiary to provide a specific

set of Medicaid-covered services to Medicaid beneficiaries.

40

Specifically, states will receive a 93 percent federal matching rate for medical assistance

costs for newly eligible beneficiaries in fiscal year 2019, and 90 percent thereafter. States

receive this federal matching rate for the non-benefit portion of MCO capitation payments

if states transfer the financial risk associated Medicaid beneficiaries to the MCO. In

addition, Arkansas receives this federal matching rate for premiums to qualified health

plans for these beneficiaries.

41

Costs for developing the IT systems may be eligible for a 90 percent federal match rate

and 75 percent match rate for ongoing maintenance and operation, including staffing

costs.

Page 25 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

or provide beneficiary supports, such as employment services. Kentucky

officials reported piloting elements of Medicaid work requirements using

its SNAP Employment and Training program. Similarly, Arkansas officials

sought a waiver to be able to use TANF funds to provide employment

services to individuals without children in order to serve Medicaid

beneficiaries subject to work requirements.

42

New Hampshire also used

TANF funds to provide employment services to Medicaid beneficiaries

who were also enrolled in TANF.

CMS does not consider administrative costs when approving any

demonstrations—including those with work requirements—though these

costs can be significant. The agency has recently taken steps to obtain

more information about demonstration administrative costs. However, we

identified various weaknesses in CMS’s oversight of administrative costs

that could result in states receiving federal funds for costs to administer

work requirements that are not allowable.

CMS’s demonstration approval process does not take into account the

extent to which demonstrations, including those establishing work

requirements, will increase a state’s administrative costs. CMS policy

does not require states to provide projections of administrative costs in

their demonstration applications or include administrative costs in their

demonstration cost projections used by CMS to assess budget neutrality.

CMS officials explained that in the past demonstrations had generally not

led to increases in administrative costs, and as such, the agency had not

seen a need to separately consider these costs.

However, the officials told us and have acknowledged in approval letters

for demonstrations with work requirements, that demonstrations may

increase administrative costs. Kentucky provides an example of this,

reporting to us estimated administrative costs of approximately $270

million—including about $200 million in federal funds—to implement the

demonstration over 2 years. However, neither Kentucky nor the other four

selected states provided estimates of their administrative costs in their

applications to CMS, and CMS officials confirmed that no additional

42

As of June 2019, information on the status of this waiver application was not available

from the Arkansas officials we spoke with.

Weaknesses Exist in

CMS’s Oversight of

Administrative Costs

of Demonstrations

with Work

Requirements

CMS’s Approval Process

Does Not Take into

Account How a

Demonstration Will Affect

Administrative Costs

Page 26 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

information on administrative costs was provided by the states while their

demonstration applications were being reviewed.

By not considering administrative costs in its demonstration approval

process, CMS’s actions are counter to two key objectives of the

demonstration approval process: transparency and budget neutrality.

• Transparency. CMS’s transparency requirements are aimed at

ensuring that demonstration proposals provide sufficient information

to ensure meaningful public input. However, CMS officials told us that

they do not require the information states provide on the expected

changes in demonstration expenditures in their applications to

account for administrative costs. This information would likely have

been of interest in our selected states, because public commenters in

each state expressed concerns about the potential administrative

costs of these demonstrations. In prior work, we reported on

weaknesses in CMS’s policies for ensuring transparency in

demonstration approvals.

43

• Budget neutrality. The aim of CMS’s budget neutrality policy is to

limit federal fiscal liability resulting from demonstrations, and CMS is

responsible for determining that a demonstration will not increase

federal Medicaid expenditures above what they would have been

without the demonstration. However, CMS does not consider

administrative costs when assessing budget neutrality. For three of

our five selected states, the demonstration special terms and

conditions specify that administrative costs will not be counted against

the budget neutrality limit.

Even though demonstrations’ administrative costs can be significant,

CMS officials said the agency has no plans to revise its approval

process—either to (1) require states to provide information on expected

administrative costs to CMS or the public, or to (2) account for these

costs when the agency assesses whether a demonstration is budget

neutral. CMS officials explained that the agency needs more experience

43

In 2019, we reported that CMS’s approach to ensuring public transparency had

weaknesses when states proposed making major changes to their demonstrations

through amendments or major changes to pending applications. For example, we found

that enrollment information was not disclosed when Arkansas and New Hampshire each

sought to amend their demonstrations to add a work requirement. We made

recommendations, with which CMS concurred, for the agency to develop policies to

improve transparency when states propose major changes. See GAO, Medicaid

Demonstrations: Approvals of Major Changes Need Increased Transparency,

GAO-19-315 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 17, 2019).

Page 27 GAO-20-149 Medicaid Demonstration Administrative Costs

with policies that require administrative changes under a demonstration

before making any revisions to its processes. Without requiring states to

submit projections of administrative costs in their demonstration

applications, and by not considering the implications of these costs for

federal spending, CMS puts its goals of transparency and budget