IN

THE

UNITED

STATES

DISTRICT COURT

FOR

THE DISTRICT

OF

COLUMBIA

1

1

V.

)

1

GALE

A.

NORTON, Secretary

of

1

the Interior,

&

&,

)

1

Defendants.

1

ELOUISE PEPTON COBELL,

a

al.,

1

No. 1:96CV01285

Plaintiffs,

1

(Judge Lamberth)

DEFENDANTS’ OPPOSITION TO

PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR

A

PROTECTIVE ORDER REQUIRING

DEFENDANTS TO

PAY

PLAINTIFFS’ EXPERT DEPOSITION FEES AND EXPENSES

Plaintiffs have moved for a “protective order” under Rule 26(b)(4)(C) and Rule 26(c) of

the Federal Rules

of

Civil Procedure concerning expert witness depositions that have already

been completed, when what Plaintiffs really want is reimbursement for

fees and expenses

purportedly related to

the

completed depositions

of

their experts, regardless

of

whether the costs

are reasonable or unconscionable, documented

or

entirely unsubstantiatcd. Rather than present a

cogent explanation

of

the charges and Plaintiffs‘ entitlement to them, most of Plaintiffs’ motion is

spent complaining that Defendants have not simply paid the bill

-

a

bill

totaling nearly

$71,000

for fewer than

40

hours of deposition, almost half

of

which is composed of blatant overcharges

and unsubstantiated expenses.’ Given these excesses, Plaintiffs‘ motion should be denied.

Defendants will not waste the Court’s time by refuting,

tit

for tat, every exaggeration and

misstatement Plaintiffs tender Concerning the “background” of the parties’ discussions about

reirnbursemcnt. Plaintiffs’ portrayal

is

not accurate, but none of it

is

pertinent

to

the ultimate

issue concerning the amount

of

reimbursement due. Suffice

it

to say that when Defendants

objected to Plaintiffs’ self-serving mischaracterizations of the parties’ discussions, Plaintiffs

chose to quarrel and accuse rather than focus on making certain that the materials they provided

to Defendants adequately explained and substantiated every dollar

of

their claim. Even upon

filing the instant motion, Plaintiffs have done nothing fiirther to substantiate

or

document their

Plaintiffs demand reimbursement for fees and expenses that are unreasonable,

unrecoverable and, in some cases, entirely undocumented. Defendants are not opposed to paying

Plaintiffs for the reasonable expenses, actually incurred, of their experts' depositions in

accordance with the Federal Rules, but nothing obligates Defendants to blindly pay whatever

amount Plaintiffs claim. Defendants object to Plaintiffs' claim to the extent it seeks

reimbursement for

(1)

unreasonably high witness fees,

(2)

overcharges for time,

(3)

exorbitant,

lavish expenses and

(4)

undocumented fees or costs.

In

turn, Defendants are also entitled to

setoff against the reasonable amount due Plaintiffs all corresponding reasonable fees and

costs

that Defendants incurred

in

producing their own experts for deposition by Plaintiffs. With these

adjustments, Plaintiffs are not due the

$70,990

their motion suggests, but an amount closer to

$25,780.

Plaintiffs basically contend that they have submitted a bill to Defendants and Defendants

must pay it, regardless

of

how unreasonable or questionable the charges are and without setoff

for any expenses due Defendants. Their position is as unreasonable as it is untenable. Had

Plaintiffs submitted a statement containing only reasonable and documented charges, the matter

could have been resolved more readily. Plaintiffs neglect to mention, however, that the amount

they seek is padded with excesses, such

as:

a

$1,000

hotel bill for a one-day deposition;

0

a lavish

$139

meal at an exclusive restaurant;

over

$100

of charges at

a

hotel lobby bar;

hourly fees of

$1,000

for testimony by one expert;

reimbursement claim.

2

time charged for attending another expert’s deposition;

charges for meeting with Plaintiffs’ counsel; and

what appears

to

be first class airfare.

These are just examples of the excesses behind Plaintiffs’ motion.

No

litigant should have to

cover such spending.

As

Plaintiffs note in their motion, the parties did discuss prior to the depositions whether

the government would pay for the experts’ travel time to Washington. The parties did reach an

agreement that such billable travel time would not exceed twelve to thirteen hours round trip per

witness. The parties, however, did not agree to abandon the prescription in the Federal Rules that

charges for expert fees and related travel must be reasonable to be reimbursable.

No

basis exists,

therefore, to assert that every dollar Plaintiffs claim is recoverable simply because the charge

appears

on

their list.

ARGUMENT

I.

A

Party Seekinp Reimbursement Under Rule

26

Bears

The

Burden

Of Proving Reasonable Expenses

A

party seeking reimbursement of deposition fees bears the burden of proving

reasonableness. Royal Maccabees Life

Ins.

Co.

v. Malachinski,

No.

96-C-6135,

2001 WL

290308,

at*

16

(N.D.

111.

Mar.

20,2001).

Unless Plaintiffs have documented each item of

expense for which they seek reimbursement with, for example, receipts, it necessarily follows

that they cannot discharge their burden of proving they were reasonable.

In

Part

I11

below,

Defendants identify those charges claimed by Plaintiffs that are unreimbursable because they are

not substantiated.

3

11.

A

Partv

Is

Not

Required

To

Pav More Than The Actual, Reasonable

Cost

Of

Expert Discovery

Rule 26 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides that

a

party deposing an

adversary’s expert should pay for the “reasonable” cost

of

providing that discovery. Fed.

R.

Civ.

P.

26(b)(4)(C) (“party seeking discovery [should] pay the expert

a

reasonable fee for time spent

responding to discovery”). The obligation is also reciprocal: Plaintiffs are equally obligated

under the same rule to pay the reasonable cost

of

producing Defendants’ experts for deposition.

The

key limitation to recovery of such fees and expenses, however, is that they be

“reasonable.” If one side decides to spend lavishly

on

an expert, the opposing side should not be

obligated to pay for that exorbitance.

As

one court put it, “[wlhile plaintiff may contract with

any

expert of plaintiffs choice and,

by

agreement, that expert may charge unusually high rates

for services, the discovery process will not automatically tax such unreasonable fees upon the

defendant.” Bowen v. Monahan,

163

F.R.D. 571, 574

(D.

Neb.

1995)

(ordering defendant to pay

half of expert’s proposed fee); accord

U.S.

Energy

COT.

v.

NUKEM,

Lnc., 163

F.R.D.

344,347

(D.

Colo.

1995)

(“[U]nless

the courts patrol the battlefield

to

insure fairness, the circumstances

invite extortionate fee setting.”).

In determining whether an expert’s fee

is

reasonable, courts consider the following

factors:

(1)

the witness’s area of expertise;

(2)

the education and training required to provide the

type of expert insight that is sought;

(3)

prevailing rates of other comparable experts;

(4)

the

nature, quality and complexity of the discovery responses provided;

(5)

the cost

of

living in the

particular area; and (6) any other factors likely

to

be

of

assistance to the court in balancing the

interests implicated by Rule 26.

a..

Bowen, 163 F.R.D. at

573;

accord Magee v. Paul Revere

4

Life

Ins.

Co., 172

F.R.D.

627,645 (E.D.N.Y. 1997) (commenting that none of these factors has

“talismanic qualities” but serve as a “guide for the Court”). The same test of reasonableness

applies to the recovery of related expenses. See,

e.g,

Frederick

v.

Columbia University, 212

F.R.D.

176,

177-78 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (“defendants are not required to provide first class travel or

first class accommodations” for plaintiffs’ expert);

cf.

Mathis v. Nynex, 165 F.R.D. 23 (E.D.N.Y

1996) (deposing party not obligated to pay for expert’s copy

of

transcript).

Defendants identify below each fee charge and expense item that they challenge and

explain the basis for their objection. With but one exception, Defendants will not quarrel with

the professional rates applied by Plaintiffs’ experts, but Defendants do object where the experts

have padded their hours. In other instances, Plaintiffs have claimed reimbursement for expenses

that they do not bother even to document, much less itemize. These costs are all objectionable

because Plaintiffs have failed to prove these unsubstantiated expenses are reasonable. Finally,

other expenses, although documented, are just plain unreasonable.

Table

A,

submitted herewith as Exhibit

1,

summarizes Defendants’ objections and the

adjustments that the Court should make to Plaintiffs’ claim. Column one lists each

of

Plaintiffs’

experts and, for convenience

of

reference, notes each expert’s affiliated

firm

where one exists2

The second column lists the number of hours that the expert was depo~ed.~ (One expert, Dwight

Duncan, was deposed

in

excess of eight hours because he was deposed as both an affirmative and

rebuttal witness.) The next three columns summarize the fees and expenses that Plaintiffs appear

In

some

cases, documents provided

by

Plaintiffs bear letterhead

of

only the expert’s affiliated

firm.

The length of deposition

is

a

useful yardstick for considering whether certain claimed expenses

are reasonable (e.g.,

3

days of lodging are patently unreasonable for a 2-hour deposition).

5

to claim for each listed witness. The next three columns summarize the dollar value

of

the

various objections Defendants assert in connection with the claimed amounts. The last two

columns,

on

the far right, summarize the total amount of fees and expenses that should be

disallowed for each witness, and the dollar value of Plaintiffs’ claim after adjusting for

disallowed amounts. The bottom row provides a grand total for the major categories.

111.

Plaintiffs’ Claimed Fees

And

Expenses Require

-

Adjustment Because They

Are

Excessive And,

In

Several Cases, Unproven

Defendants set forth below their objections to the fees and expenses Plaintiffs have

claimed in connection with the deposition of each

of

their expert witnesses. For ease

of

reference, Defendants will address each objection, witness by witness.

1.

Richard Fasold

Mr. Fasold appeared for deposition

on

March

21,2003.

According to the transcript, his

deposition commenced about

9:30

a.m. and concluded shortly before

5:OO

p.m., with a break for

lunch.4 For this one day

of

deposition.

Mr.

Fasold submitted

an

invoice totaling

$14,416.77.

That invoice includes charges

of

$1,000

per hour for the time spent in deposition, and

$500

per

hour for exactly six hours travel

to

Washington and back home. It includes

$402.47

for

-

not one

-

but two nights of lodging, while other receipts for his trip clearly indicate that

Mr.

Fasold

All deposition times cited in

this

response are based on the time entries made by the

stenographer on the record for each session.

6

remained in Washington for several more days, presumably at Plaintiffs’ request5 For example,

his bill includes $1 14.30 in charges for

two

dinners.6

A.

Mr. Fasold’s Rate

Is

Unreasonable

A

professional fee of

$1,000

per hour for deposition testimony and a base rate

of

$500

per

hour is unconscionable. Mr. Fasold testified at trial that he is

a

business partner and friend of

Plaintiffs’ lead counsel, Dennis Gingold. He claims his customary rate is

$500

per hour, but that

he doubles the rate for time spent testifying. Phase 1.5 Trial Tr., May 14,2003 a.m., at 71:21-

72:9

(R.

Fasold) (attached at Exhibit

2).

Although Mr. Fasold is surely overpaid at

$500

an hour,

Mr. Fasold did charge

his

stated rate for travel time within the limits agreed to by Defendants last

March,

so

Defendants do not object here to paying

$500

per hour for travel. Defendants do,

however, object to paying anything more for his time spent in deposition.

&,

s,

Frederick,

212 F.R.D. at 177 (exorbitant $975 hourly deposition fee for toxicologist reduced to $375);

Edin

v. Paul Revere Life

Ins.

Co.,

188

F.R.D.

543,

547

(D.

Ariz.

1999) (refusing to condone under

Rule

26

an “extortionist practice” of charging multiples of usual rate for testimony).

B.

Some of Mr. Fasold’s Expenses Are Unreasonable

The records submitted by Plaintiffs indicate that Mr. Fasold traveled to Washington

several days early, presumably

to

observe depositions of other expert witnesses. Given that Mr.

Fasold’s

own

deposition was completed by

5:OO

p.m.

on

March 21, it

is

not reasonable

to

ask

Defendants did not request

Mr.

Fasold’s presence beyond his own deposition.

Based upon the receipts for the meals, it also appears that Mr. Fasold dined with another party

and then simply billed for one-half the amount of the total. Defendants cannot confimi whether

the bills reflect the actual cost

of

Mr.

Fasold’s meal

or

whether the amount claimed would

subsidize the meals

of

Mr. Fasold’s guest.

7

Defendants to pay for any of Mr. Fasold’s lodging or meals after his own deposition concluded.

At that time, as far as Defendants were concerned, he was free to return home. The charge for

his second night of lodging and second dinner should be disallowed as unreasonable.

2.

John

Wright

John

Wright’s deposition was held

on

March 13,2003. It began at about

1O:lO

a.m. and

ended shortly after 3:00, for

a

total duration just shy of five hours, including all breaks. Mr.

Wright’s bill

for

this part-day deposition is

$8,848.23.

Although Plaintiffs’ counsel agreed that

experts would not bill travel time in excess of six hours in either direction, Mr. Wright billed a

total of 13.3 hours for

his

trip to Washington and return travel home, exceeding the agreed

ceiling. Although the transcript shows that the deposition took less than five hours to complete,

Mr.

Wright billed for

5.4

hours. The time exceeding five hours is also unreasonable.

Once he amved in Washington, Mr. Wright treated himself to

a

$325 (plus taxes) per

night room at the Willard Hotel, one of the priciest hotels in Washington. Although his

deposition took less than five hours and was finished by three o’clock, Plaintiffs seek to recover

three

days lodging at the Willard. His hotel bill includes over

$100

in what appear to be charges

fiom

the hotel’s lobby bar.7 His invoice includes a $139 dinner at the Oceanaire restaurant and an

additional $230 unexplained charge from his travel agent.

Defendants do not object to paying for one night

of

lodging and related meals,

if

billed at

a reasonable amount. Defendants do object, however, to lavish spending on premium hotels,

exclusive restaurants, and for more than one day of accommodations. The Willard room

was

The Willard hotel bill lists three charges from “Round Robin Beverage.” When contacted to

explain the reference, the hotel identified it as being the lobby bar. The hotel’s web site also

gives a similar description.

8

$325

a night plus taxes; by comparison the government per diem for Washington,

D.C.

is

$200

per day for all meals and lodging. Defendants acknowledge that it may not be possible for non-

government contractors to obtain government rates, but when an opposing expert consciously

chooses premium accommodations, the taxpayers should not be compelled to underwrite the

frivolity. Defendants, therefore, object to paying more than

$200

per night for lodging and more

than

$50

for a dinner.

3.

Landy Stinnett

A. Mr. Stinnett’s Hours Are Wildly Overstated

Mr. Stinnett appeared for deposition on March 18,2002. It began at

9:55

a.m. and ended

by

1

:49

p-m., for a total duration of less than four hours including all breaks. Plaintiffs have

presented a bill

of

$5,368.77 in connection with this brief deposition. Although the deposition

lasted less than four hours, Mr. Stinnett has billed time

of

twenty-four hours. The bill lists a

charge of four hours of travel each way, plus a full eight-hour

day

for

“preparation”

in

Washington the day before his deposition, plus eight hours

of

time for less than four hours of

testimony. Such exorbitant billing is patentIy unreasonable and not reimbursable under Rule

26.

Defendants

do

not object to the travel time billed or to four hours for deposition time, but do

object to all other billed time as excessive.

Although there does not appear to be a

set

rule in this district concerning whether

“preparation” time

is

a reasonable charge under Rule 26, the better view is not to authorize

it.

Some courts have disallowed such fees absent compelling circumstances, while others have

allowed some preparation time in the belief that a deposition should proceed more efficiently

when the expert has refreshed his recollection. See Magee, 172

F.R.D.

at 646 (listing cases on

9

both sides); compare

M.T.

McBrian. Inc. v. Liebert

Corp.,

173 F.R.D. 491

(N.D.

111.

1997) (no

preparation fee allowed for contract case)

y&

S.A.

Healv

Co.

v. Milwaukee MetroDolitan

Sewerage Dist., 154 F.R.D. 212, 214

(E.D.

Wis.

1994)

(testimony required review of one

hundred schedules attached to expert report). The better approach is to prohibit recovery

of

such

costs absent clear proof that the expert had to undertake specific work to ready himself for

examination. In this case,

no

such independent work should have been necessary

-

each expert

had submitted his report just

two

to three weeks prior to his deposition.

In

Mr. Stinnett’s case,

his expert report was only four pages

long.

More important, authorizing recovery for preparation time opens the door to abuse. It

tempts adversaries to charge for time that the expert actually spent working with the attorney who

will defend his deposition. Defendants note that the full eight hours Mr. Stinnett charged for

“preparation” occurred

after

he traveled to Washington for the deposition, suggesting that this

time was likely far more beneficial

to

Plaintiffs’ counsel than to Defendants.

Courts

have

refused the invitation

to

shift the cost of conference time with defending counsel to the deposing

party. See Magee, 172 F.R.D. at 647 (approving of some reasonable preparation time for expert

but not that billed for time “preparing the attorney who retained him”). Thus, Defendants object

to paying more than 12 hours for Mr. Stinnett’s time

(8

hours travel and 4 hours in deposition).*

’

Should the Court determine that reasonable preparation time is recoverable, Defendants ask the

Court

to permit Defendants to amend their compensation claim to include preparation time spent

by Defendants’ own experts prior to deposition. Presently, Defendants do not include such

charges in calculating the amount of setoff to which Defendants are entitled. Preliminary inquiry

indicates that if such preparation time were included, it would add approximately $13,500 to

Defendants’ reimbursement claim because

of

the depositions

of

Edward Angel (42.5 preparation

hours at

$105

per hour); Alan Newel1 (34 preparation hours for two deposition days at $150 per

hour); and Dr. David Lasater (7.9 preparation hours for two deposition sessions at $500 per

hour).

10

B.

Expenses Relating To Mr. Stinnett’s Travel Are Unsubstantiated

Plaintiffs also seek compensation for related expenses in the amount of $1,768.77. The

bill

from Pincock Allen

&

Holt, Mr. Stinnett’s employer, merely lists two dollar figures,

$1,110.77 for “Expenses” and $658.00 with a label of “American Express“ without explanation.

No

receipts or other proof of the expenses have been provided. None of the papers Plaintiffs

submitted to Defendants or to the Court (with the motion) prove that these expenses were

incurred. Without receipts or other explanation to demonstrate these costs were actually incurred

and are reasonable, Defendants cannot properly be asked to pay them. Defendants, thus, object

to all expenses listed by Plaintiffs in connection with Mr. Stinnett’s deposition.

4.

Paul M. Homan

Paul Homan appeared for deposition on April 9,2003.

His

deposition commenced at

10:06

a.m. and concluded at 5:03 p.m., for a total duration of

7.2

hours, including all recesses.

Plaintiffs, however, seek to recover expert fees for twenty-five hours. At a billable rate of

$500

per hour, the total charge Plaintiffs seek to impose is $12,500 for less than one

full

eight-hour

day of deposition.

If

approved, Plaintiffs’ demand would ratchet Mr. Homan’s effective rate up

to more than $1,700 per

hour

of deposition. The amount they seek is patently unreasonable.

As noted above with respect

to

Mr. Stinnett’s bill,

it

is not prudent

to

allow a party to

charge its adversary for the expert’s “preparation” in this case.

Mr.

Homan testified on April

9,

a

scant 10 days after he completed his expert report. The material, therefore, should have been

completely fresh

in

his mind. Mr. Homan’s deposition revealed also that much of the material in

his “report” was merely a rehash

of

the strategic plan he submitted to Congress while Special

Trustee, see generally Homan Deposition Tr. at 58-61(April9,2003) (attached at Exhibit

3),

11

afong with some more current observations he had included in testimony to Congress.

So,

there

was not much of anything “new” that Mr. Homan needed to review before his deposition. Only

the fee for his actual time in deposition should be recoverable.’

5.

Matthew Gabriel

Matthew Gabriel’s only deposition, held on March

1

1,

2003,

was brief

-

it

lasted a mere

three hours and twenty-three minutes; it was the second expert deposition that day, and ended at

458

p.m.. The bill presented by Plaintiffs totals $4,227.36. This bill reflects 21.6 hours of

billable time: 2.3 hours of billable time for meeting with Plaintiffs’ counsel for a “briefing on

disposition [sic],” 12.4 hours

of

round-trip travel time, and 3.5 hours of time billed, not for

Mr.

Gabriel’s own deposition, but for observing the McQuillan deposition earlier in the day.

If

Plaintiffs’ counsel desire to confer with their expert to be “briefed” on his expected testimony,

that is their prerogative, but it should not be at Defendants’ expense.

lo

Likewise, if an expert

wants to watch another deposition, the time he devotes to that activity is not properly chargeable

to his adversary;

it

is for his own benefit and for his own client’s account.

Mr.

Gabriel’s invoice reflects expenses

of

$1,527.36, including

$1,038

for airfare,

$342.36 for hotels and $1 12.45 for cabs. While most

of

the charges appear reasonable, the hotel

Although Defendants will not here contest whether a fee of

$500 per hour for Mr. Homan is

reasonable, the rate is unquestionably expensive. His high price should be considered as a factor

against allowing recovery for any preparation time. Defendants submit that his

high

hourly

rate

already reflects

his

“preparation”

-

years as a

bank

regulator and Special Trustee.

E?

The same arguments that militate against recovery of “preparation” time for Messrs. Stinnett

and Homan, above, apply even more strongly here. The time billed was expressly for meeting

with Plaintiffs’ counsel, which

should

not be recoverable even if other “preparation” work were

allowed.

12

charge appears excessive.

As

noted above, Defendants should not be required to pay more than

$200 per night for lodging,

so

the expenses require an adjustment of $142.36.

6. Alan McQuillan

Professor McQuillan appeared for a brief deposition on the morning of March 1 1,2003.

The deposition commenced at 9:40 a.m. and concluded by 12:

15

p.m., for a total elapsed time of

two

hours and thirty-five minutes. According to the text of Plaintiffs’ motion, the fees and

expenses relating to this brief deposition total $5,907.57. Not one piece of paper submitted with

Plaintiffs’ motion shows that these charges are reasonable.” Indeed, it is not even clear whether

Plaintiffs mean

to

claim any fee or expenses for the professor. Their proposed order makes no

mention of Professor McQuillan and proposes no recovery in connection with his deposition.

Having failed to substantiate any charges relating

to

the McQuillan deposition or to propose an

amount for them in their form of order, Plaintiffs are entitled

to

no reimbursement

in

connection

with the McQuillan deposition.

7.

Dwight

J.

Duncan

Dwight Duncan played two roles

in

discovery: he gave an expert report as an affirmative

expert and a report as a rebuttal expert for Plaintiffs.

In

connection with his affirmative case role,

Plaintiffs seek payment of $13,284.19, and for his rebuttal deposition, Plaintiffs demand

$6,437.30. Plaintiffs agreed to produce Mr. Duncan for

a

day of deposition on March 19,2003,

at 9:30 a.m. When that day arrived, however, the witness advised that he had

to

leave by mid-

afternoon in order to travel home. Defendants accommodated Mr. Duncan’s personal schedule

Plaintiffs appear to rely entirely upon a summary memorandum sheet prepared by Plaintiffs,

office assistant, but that sheet merely lists a total for Professor McQuillan.

13

by allowing Mr. Duncan to recess his deposition on March

19

and to complete it

on

March

25,

2003. Plaintiffs now seek to have Defendants pay for

both

of his trips, including double the

amount of billable travel time (a total of twenty-four hours), or

$6,000

just for travel fees.

In

addition, Plaintiffs want Defendants to foot the bill for all expenses in connection with

Mr.

Duncan’s

two

trips for

one

day of deposition, including

two

round-trip airfare charges

of

$2,264

and two hotel stays at more than $350 per night. These multiple charges

for

travel expenses

are patently unreasonable, and each expense

is

excessive by itself.’*

Defendants have similar objections concerning

Mr.

Duncan’s travel expenses for his

rebuttal deposition in April. That deposition was held on April 8,2003, and was concluded in

little more than ninety minutes. Mr. Duncan’s fees and expenses, however, total $6,437.30.

Again, there

is

an excessive $2,264 airfare, and this time, not one, but

two

hotel nights, at

a

cost

of $659.96. By any standard of reasonableness, these expenses are plainly excessive, especially

when the deposition was over before

11

:00

a.m.. Defendants object to paying for more than one

night of accommodations for each deposition round, and to paying hotel costs in excess of

$200

per night. Likewise, his exorbitant airfare should be reduced by one-half, to bring it in line with

what other experts charged.

8.

Plaintiffs’ Claimed Fees And Expenses Should Be Limited

To

$38.059

Defendants should not be made to bear the cost of lavish travel accommodations or extra

costs associated with an expert’s personal schedule

or

other interests. These costs, if actually

The airfare for each

of

Mr. Duncan’s trips appears to be excessive on its face. Each ticket is

more than twice that incurred by any of Plaintiffs’ other experts. Plaintiffs did not provide a

copy of any travel receipt for Mr. Duncan,

so

Defendants question whether Mr. Duncan traveled

on first class tickets. If

so,

the charges are clearly excessive.

14

incurred, should be borne by Plaintiffs. Second, Plaintiffs are not entitled to be reimbursed for

costs that they cannot substantiate by a receipt or similar transaction record.

No

compensation

should be allowed for hours that are padded or fees that are excessive.

When excessive costs and fees are eliminated and unsubstantiated charges are ignored,

the amount of reimbursement to which Plaintiffs are legitimately entitled is substantially less

than the amount they seek. Table A represents a summary of Defendants’ adjustments to

Plaintiffs‘ claimed amounts. Plaintiffs’ claim reimbursable fees and expenses

of

$70,990. After

all of the adjustments set forth above are made, that number falls

to

$38,058.79. The analysis,

however, cannot end there. Like Plaintiffs, Defendants also produced several experts for

deposition at Plaintiffs’ behest. Because Defendants are entitled to reimbursement of reasonable

fees and expenses of these depositions under Rule

26,

these amounts should be setoff against

whatever amount the Court determines that Plaintiffs are entitled to recover. That final

adjustment is addressed in the next section.

IV.

Defendants

Are

Entitled

To

A

Setoff

As

Reimbursement

For

Plaintiffs’ Deposition

Of

Defendants’ Experts

Plaintiffs took four discovery depositions of Defendants’ experts. Edward Angel

appeared

on

March 17,2003 for

6.5

hours

of

examination. Alan Newcll appeared for almost

two

days of deposition,

on

March 20, 2003 for 7.9 hours, and again

on

April

28,

with

4.S

more

hours

of

examination. Plaintiffs deposed Dr. David Lasater twice, once as an affirmative witness

and later in his role

as

a rebuttal witness. Dr. Lasater appeared

on

March 12,

2003

for

7.2

hours

of

deposition and

on

April

8,2003

for

5

hours of deposition.

Based

on

the contract rates at which each of these experts charges the governlent, the

fees associated with each witness’s testimony are siniple

to

compute. Defendants are making

no

15

claim for reimbursement of any fees relating to travel time. Defendants also submit that no fees

should be charged by either side for so-called “preparation” time in this case, and

so

none is

included here. Based on the deposition time noted

by

the court reporter and each expert‘s

contract rate,13 Defendants request reimbursement for expert fees in the following amounts:

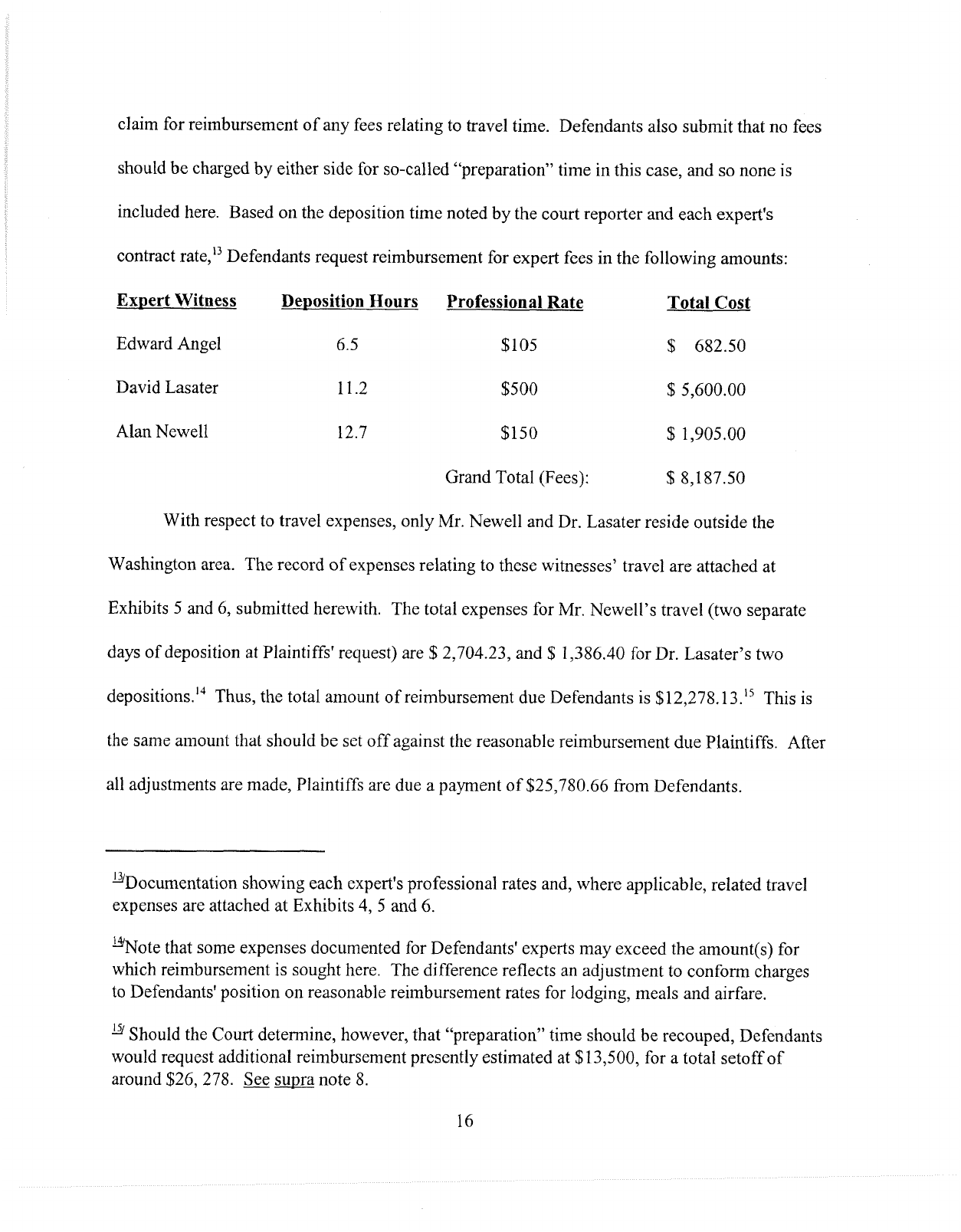

Expert Witness Deposition Hours Professional Rate Total

Cost

Edward Angel 6.5 $105

$

682.50

David Lasater 11.2

$500

$

5,600.00

Alan Newell 12.7

$150

$ 1,905.00

Grand Total (Fees):

$

8,187.50

With respect to travel expenses, only Mr. Newell and Dr. Lasater reside outside the

Washington area. The record of expenses relating to these witnesses’ travel are attached at

Exhibits

5

and 6, submitted herewith. The total expenses for Mr. Newell’s travel (two separate

days

of

deposition at Plaintiffs’ request) are $2,704.23, and

$

1,386.40 for Dr. Lasater’s

two

deposition^.'^

Thus, the total amount of reimbursement due Defendants is $12,278.13.’’ This is

the same amount that should be

sct

off against the reasonable reimbursement due Plaintiffs. After

all adjustments

are

made, Plaintiffs are due a payment of $25,780.66

from

Defendants.

gDocumentation showing each expert’s professional rates and, where applicable, related travel

expenses are attached at Exhibits

4,

5

and

6.

3Note that some expenses documented for Defendants’ experts may exceed the amount(s) for

which reimbursement is sought here. The difference reflects an adjustment to conform charges

to

Defendants’ position on reasonable reimbursement rates for lodging, meals and airfare.

Should the

Court

determine, however, that “preparation” time should be recouped, Defendants

would request additional reimbursement presently estimated

at

$I

3,500,

for

a

total setoff of

around $26,278. See supra note

8.

16

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, Defendant's motion for a protective order concerning expert witness

fees should

be

denied.

Instead, the

Court

should order Defendants to pay, and Plaintiffs to accept,

a payment

of

$25,780.66, representing the net amount due for fees and expenses of all expert

depositions conducted by either side

in

connection with discovery during Phase 1.5.

Dated: October 24,2003 Respectfully submitted,

ROBERT

D.

McCALLUM, JR.

Associate Attorney General

PETER

D.

KEISLER

Assistant Attorney General

STUART E. SCHFFER

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

J.

CHRISTOPHER

KOHN

Director

SANDRA

P.

SPOMER

D.C. Bar

No.

261495

Deputy Director

JOHN

T. STEMPLEWICZ

Senior Trial Counsel

MICHAEL

J.

QUI"

D.C.

Bar

No.

401376

Trial Attorney

Conimercial Litigation Branch

Civil Division

P.O. Box

875

Ben Franklin Station

Washington, D.C. 20044-0875

(202) 514-7194

17

THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR

THE DISTRICT

OF

COLUMBIA

ELOUISE

PEPION

COBELL,

3

&,

)

)

Plaint

i

ffs,

1

)

v.

)

Case

No.

1

:96CV01285

)

(Judge Lamberth)

GALE

A.

NORTON, Secretary of the Interior,

al.,)

1

Defendants.

1

ORDER

Upon

consideration

of

Plaintiffs' Motion for a Protective Order Requiring Defendants to

Pay Plaintiffs' Expert Deposition Fees and Expenses, Defendants' opposition thereto and request

for setoff, and the entire record herein, it is hereby

ORDERED,

that both Plaintiffs and Defendants are entitled to recover the reasonable

expenses relating to the production

of

their respective experts for deposition during discovery for

trial phase

1.5,

and that after all such reasonable expenses are calculated, Plaintiffs are due

a

net

sum

of

$25,780.66; and

it

is further

ORDERED, that Defendants' shall pay to Plaintiffs, within twenty (20) days of this order

Twenty-five Thousand Sewn Hundred Eighty dollars and Sixty-six cents ($25,780.66) to

reimburse them for the reasonable

costs

of presenting their experts for deposition, net of all

reasonable setoff to compensate Defendants' for their corresponding reasonable expenses of

producing their experts for deposition during trial phase 1.5; and it is further

ORDERED

that Plaintiffs motion for a protective order

is

denied as MOOT.

SO

ORDERED

this

day of

,2003.

ROYCE

C.

LAMBERTH

United States District

Judge

2

cc:

Sandra

P.

Spooner

John

T.

Stemplewicz

Commercial Litigation Branch

Civil Division

P.O. Box 875

Ben Franklin Station

Washington,

D.C.

20044-0875

Fax (202)

514-9163

Dennis

M

Gingold,

Esq.

Mark Brown,

Esq.

1275 Pennsylvania Avenue,

N.W.

Ninth Floor

Washington,

D.C.

20004

Fax (202)

3

18-2372

Keith Harper,

Esq.

Richard

A.

Guest,

Esq.

Native American Rights Fund

1712 N Street,

NW

Washington,

D.C.

20036-2976

Fax (202) 822-0068

Elliott

Levitas,

Esq.

1100 Peachtree Street, Suite 2800

Atlanta, GA 30309-4530

Earl

Old

Person

(Pro

se)

Blackfeet Tribe

P.O.

Box

850

Browning,

MT

59417

(406) 338-7530

CERTIFICATE

OF

SERVICE

I

declare under penalty of perjury that, on October 24,2003 I served the foregoing

Defendants

’

Opposition to Pluintiffs

’

Motion for

u

Protective Order Requiring Defendants to

Puy

Plainti&

’

Expert Deposition Fees and Expenses

by facsimile in accordance with their

written request

of

October 3

1,2001

upon:

Keith Harper,

Esq.

Richard A. Guest,

Esq.

Native American Rights Fund

1712

N

Street,

N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-2976

(202) 822-0068

Dennis M. Gingold,

Esq.

Mark Kester Brown,

Esq.

607

-

14th Street,

hW,

Box

6

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202)

3

18-2372

Per the Court’s Order

of

April 17,2003,

by facsimile and by

US.

Mail upon:

By

U.S.

Mail upon:

Earl Old Person

(Pro

se)

Blackfeet Tribe

P.O.

Box 850

Browning, MT 5941

7

(406) 338-7530

Elliott Levitas, Esq

1100

Peachtree Street, Suite

2800

Atlanta,

GA

30309-4530

Kevin P. ngston