1

Whole Health System Approach

to Long COVID

Patient-Aligned Care Team (PACT) Guide

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

August 1, 2022

2

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is leading an effort to

equip health care providers with a Veteran-centered Whole Health System approach to caring for Veterans

with Long COVID, also known as post-COVID-19 conditions (PCC). Whole Health is an evidence-informed,

multi-disciplinary, personalized, Veteran-driven approach that empowers and equips Veterans to take charge

of their health and well-being, and to live life to the fullest.

Organizations across the world have defined Long COVID with differing parameters. Diagnosing and defining

Long COVID is complicated as there are many signs, symptoms, and conditions that are associated with the

syndrome. Additionally, it is important to separate three things: pre-existing symptoms or conditions, those

that have worsened, and those that are new since an initial COVID-19 diagnosis. Risk factors for developing

Long COVID signs and symptoms include female sex (Pelà G, 2022) (Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, 2022)

,

respiratory symptoms at the onset, and the severity of the illness (Asadi-Pooya AA, 2021). At the time of this

writing, it is estimated that 4-7% of those diagnosed with COVID-19, or 2% of the U.S. population, will develop

Long COVID (Xie Y, 2021)

. Based on approximately 600,000 known Veterans with a diagnosis of COVID-19,

this equates to 24,000-42,000 Veterans. However, these numbers have the potential to be much higher, as

the VA has more than 6 million Veterans in care.

VA’s Office of Research and Development, the Long COVID Community of Practice, and the Long COVID

Integrated Project Team are working to organize, support, and report on the development of a national

program to help all Veterans who have Long COVID. They collaborated to produce this document for health

care providers to better facilitate defining, assessing, referring, and managing common Long COVID signs,

symptoms, and potential subsequent conditions using a Whole Health System approach. It is not intended to

replace clinical judgment. Rather, it provides suggestions for health care providers as they engage in shared

health care decision-making with Veterans who have this syndrome. The information available on Long

COVID is ever changing. This document will be periodically updated and republished as the scientific

community learns more about Long COVID.

Definition of Long COVID, Post-COVID-19 Conditions and Post-Acute

Sequalae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection

As mentioned above, organizations have defined Long COVID with differing parameters. The Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) define Long COVID as “new or

worsening symptoms” from “4 weeks after first being infected” with COVID-19. According to the CDC, the

term “post-COVID conditions” is an umbrella term for the wide range of physical and mental health

consequences that are present four or more weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection, including by patients who

initially had mild or asymptomatic COVID-19. NIH employs the term, Post-Acute Sequalae of SARS-CoV-2

infection (PASC), the result of the direct effects of the virus. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines

Long COVID as symptoms “lasting greater than 2 months, starting within 3 months from the onset” of COVID-

19.

Signs and symptoms associated with Long COVID vary widely and can last for weeks, months, or years. In

some individuals, signs and symptoms may resolve over time without treatment. Common

signs and

symptoms include tiredness or fatigue that interferes with daily life, signs and symptoms that get worse after

physical or mental effort (post-exertional malaise), respiratory symptoms, cardiac symptoms, neurologic

symptoms, digestive symptoms, joint or muscle pain, rash, changes in menstrual cycles, and others. The

presentation of signs, symptoms and severity range widely making them difficult to diagnose. This guide

highlights some of the more common Long COVID signs, symptoms, and potential subsequent conditions.

3

Prepared by

The VHA Long COVID Integrated Project Team Workstream 1:

Strategies and Best Practices

With support from

The VHA Long COVID Integrated Project Team

The VHA Long COVID Community of Practice

The VHA Office of Primary Care

The VHA Office of Healthcare Innovation and Learning

The VA Office of Information & Technology, Office of the Chief

Technology Officer

The VHA Office of Healthcare Transformation

The VHA Office of Patient Connected Care and Cultural Transformation

The VHA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

VHA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services

The San Francisco VA HCS Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

4

DIRECTORY OF SIGNS, SYMPTOMS, AND OTHER POTENTIAL

CONDITIONS

One-page guides are provided for signs, symptoms, and other potential subsequent conditions. Each guide is

hyperlinked below and includes the following details: things to keep in mind, evaluation with labs and tests,

PACT management, and consult suggestions.

Quick Guides

• ANOSMIA AND DYSGEUSIA 7

•

AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM DYSREGULATION 8

•

CHEST PAIN 9

•

COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT 10

•

COUGH 11

•

DYSPNEA 12

•

FATIGUE AND ACTIVITY INTOLERANCE 13

•

HEADACHES 14

•

MENTAL HEALTH (ANXIETY, DEPRESSION, PTSD) 15

•

OTHER POTENTIAL CONDITIONS: CARDIOMETABOLIC AND AUTOIMMUNE 16

Quick Links

• APPENDIX A: OLFACTORY TRAINING 17

•

APPENDIX B: FATIGUE AND ACTIVITY INTOLERANCE 18

•

APPENDIX C: 30 SECOND SIT TO STAND TEST 20

•

APPENDIX D: COMPOSITE AUTONOMIC SYMPTOM SCORE (COMPASS 31) 21

•

RESOURCES 26

•

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES 27

5

INTRODUCTION

VA’s Office of Research and Development, the Long COVID Community of Practice, and the Long COVID

Integrated Project Team are working to organize, support, and report on the development of a national

program to help all Veterans who have Long COVID. They collaborated to produce this document for health

care providers to better facilitate defining, assessing, referring, and managing common Long COVID signs,

symptoms, and potential subsequent conditions using a Whole Health System approach. Whole Health is an

evidence-informed, multi-disciplinary, personalized, Veteran-driven approach that empowers and equips

Veterans to take charge of their health and well-being, and to live life to the fullest. (Gaudet T, 2019) (Krejci L,

2014)

As one of the largest health care systems in the United States, VHA is leading the charge to deliver care to

Veterans with Long COVID whether post-COVID-19 conditions (PCC) (direct and indirect effects of the virus)

and the subset Post-Acute Sequelae of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)

infection (PASC) (direct effects of the virus), hereafter referred to as Long COVID. At the time of this writing, it

is estimated that 4-7% (Xie Y, 2021) of those diagnosed with COVID-19, or 2% of the U.S. population, will

develop Long COVID. Based on approximately 600,000 known Veterans with a diagnosis of COVID-19, this

equates to 24,000-42,000 Veterans. However, these numbers have the potential to be much higher, as the

VA has more than 6 million Veterans in care.

Organizations have defined Long COVID with differing parameters. The Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) define Long COVID as “new or worsening

symptoms” from “4 weeks after first being infected” with COVID-19. According to the CDC, the term “post-

COVID conditions” is an umbrella term for the wide range of physical and mental health consequences that

are present four or more weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection, including by patients who initially had mild or

asymptomatic COVID-19. NIH employs the term, Post-Acute Sequalae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), the

result of the direct effects of the virus. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines Long COVID as

symptoms “lasting greater than 2 months, starting within 3 months from the onset” of COVID-19.

A challenge for many health care providers is diagnosing Long COVID because there are several signs and

symptoms associated with the syndrome, some of which may resolve without treatment over time in certain

individuals. It is important to separate pre-existing signs and symptoms from those that have worsened or

those that are new since a COVID-19 diagnosis. This document is not intended to replace clinical judgment.

Rather, it provides suggestions for health care providers as they engage in shared health care decision-

making with Veterans who have this syndrome.

This guide is broken into several sections: an Executive Summary including a navigation guide, a primer on

the Whole Health System approach, and quick reference guides for Veterans’ care. Long COVID research is

in its infancy and the information available on Long COVID is ever changing. For example, there is minimal

evidence to-date on Long COVID and special populations such as racial and ethnic minorities and

transgender people. This document will be periodically updated and republished as the scientific community

learns more about Long COVID.

6

Whole Health System Approach to Long COVID Care

Whole Health is an evidence-based, multi-disciplinary, personalized, Veteran-driven approach that empowers

and equips Veterans to take charge of their health and well-being, and to live life to the fullest. The VA has

adopted the Whole Health System approach across many health sectors.

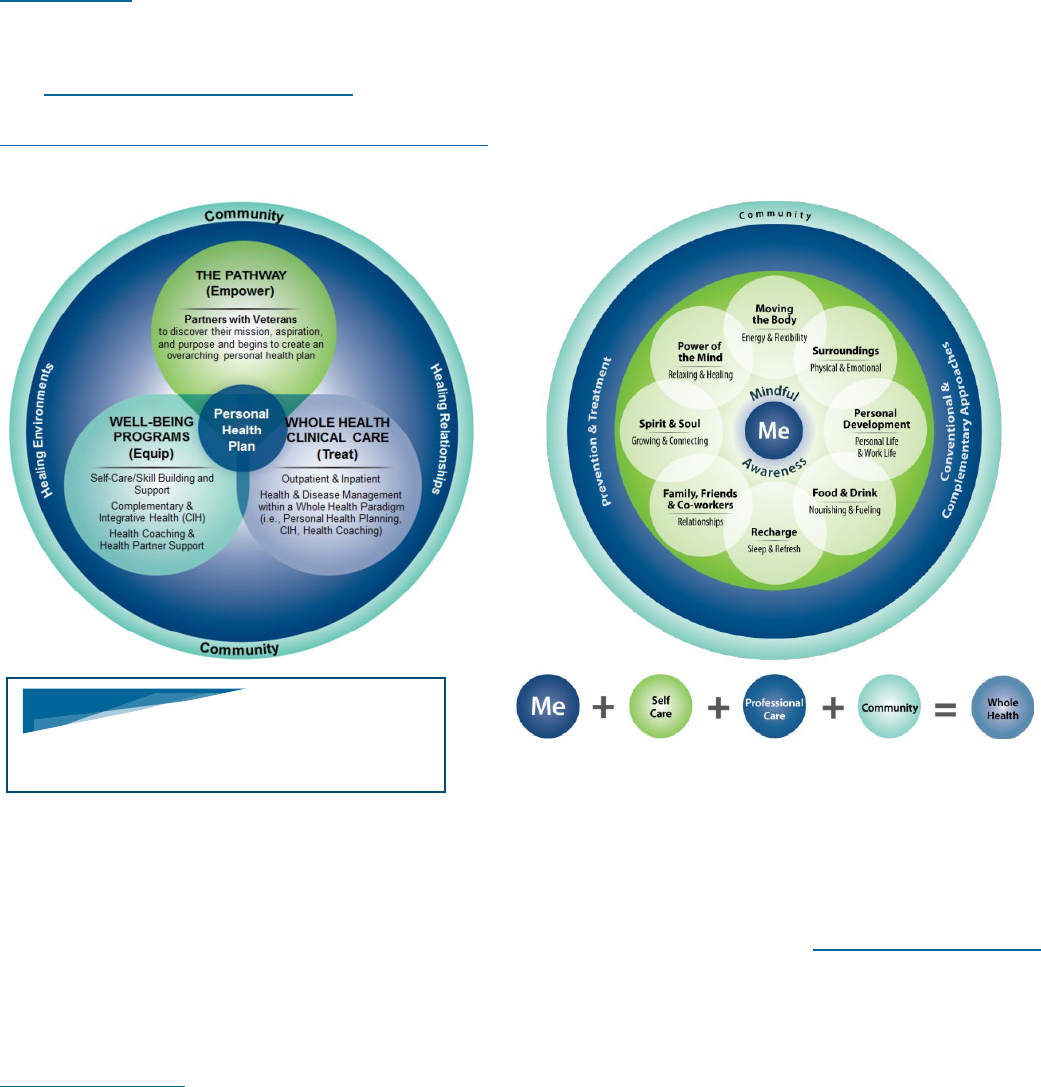

The Whole Health System approach consists of the following three components: The Pathway, Well-Being

Programs, and Whole Health Clinical Care. Included in the Whole Health System are health coaching,

complementary and integrative health approaches such as acupuncture and yoga, alongside conventional

care.

Discussing what is most important to the Veteran ensures that the Veteran and their unique circumstance is

at the center of health care, not just their signs and symptoms. This encourages and emphasizes the

Veteran’s ability to shape their health and well-being through self-care and self-management.

As part of this care, Veterans conclude their visit with a Personalized Health Plan that typically includes at

least one specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time-bound (SMART) goal. Building a SMART goal

with a provider injects the care and expertise of professional care for prevention and treatment aligned with

the Veteran’s personal health plan. A SMART goal considers a Veteran’s needs and environment, the

community of support a Veteran has, as well as those who rely on the Veteran for support, social

determinants of health, and other important factors that affect a Veteran’s everyday life. These and other

Whole Health tools help to ensure a Veteran-focused visit that empowers the Veteran to be an active

participant in their health goals.

In the following pages, we delineate an evidence-informed Whole Health System approach to Long COVID

care. Importantly, the Whole Health System of care is not solely a separate and standalone consult service or

program, rather it is a system-wide approach. This document is intended to be a broad approach, leaving

room for clinical judgment, individual circumstances, medical resources, and pre-existing referral patterns. As

the knowledge around Long COVID evolves, additional iterations of this guide will become available.

WHAT IS MOST IMPORTANT TO YOU

TO DISCUSS IN THE VISIT TODAY?

7

ANOSMIA AND DYSGEUSIA

This provides suggestions as you engage in shared health care decision-making with Veterans. It is not

intended to replace clinical judgement.

Up to 46% of patients reported anosmia at greater than 4 weeks post-COVID-19

1

(NICE, 2021), and

specifically 16% of non-hospitalized patients reported anosmia at 60- or 90-days post-COVID-19 onset.

2

(Yoo S, 2022)

Things to Keep in Mind

May need to prompt Veteran, as this may not be the primary complaint

May be associated with cognitive changes

3

(Douaud G, 2022), neurologic changes

4

(Premraj L, 2022),

phantosmia (smells that are not present) and dysosmia (altered sense of smell/taste such as excessive

chemical, salty or sour sensations)

Assess for possible contributors such as sinus disease and rhinitis

Assess the effect on food choices and quality of life

Hypertension (HTN) after anosmia and dysgeusia may occur due to increased salt placed on food

Educate on safety considerations (e.g., strategies to avoid spoiled food, increase vigilance to monitor

safety detectors in the home, etc.)

Assess pregnancy/lactation status, review teratogenic medications

Evaluation

Labs to Consider Tests to Consider

None None

PACT Management to Consider

Consults to Consider

ICD-10 Code: U09.9, Post-COVID-19 condition,

unspecified

Intranasal steroids may be used if other nasal signs

and symptoms with anosmia like congestion or rhinitis

are present; no strong data that steroids (oral or

intranasal) are significantly beneficial for isolated

post-COVID-19 anosmia

Recommend against antibiotics and Vitamin A drops

5

(Addison A, 2021)

6

(Hopkins C, 2021)

Smell/olfactory retraining and advice (Appendix A):

• The act of regularly sniffing or exposing oneself to

robust aromas with the intention of regaining a

sense of smell

Speech Language Pathology or

Occupational Therapy: olfactory

retraining, as well as additional

education and implementation

strategies to support safety

considerations related to impaired

smell

Ear, Nose, Throat (ENT) or Speech

Language Pathology: concurrent

dysphonia or dysphagia

Neurology: previous head injury or

neurologic signs and symptoms

Whole Health System approach:

Whole Health Coaching

1

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) UK, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188

2

Yoo S. Factors Associated with Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC) After Diagnosis of Symptomatic COVID-19 in the Inpatient and

Outpatient Setting in a Diverse Cohort. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Jun;37(8):1988-1995. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07523-3.

3

Douaud G. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature. 2022 Apr;604(7907):697-707. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-

04569-5

4

Premraj L. Mid and long-term neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome: A meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2022 Mar

15;434:120162. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2022.120162

5

Addison A. Clinical Olfactory Working Group consensus statement on the treatment of postinfectious olfactory dysfunction. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

2021 May;147(5):1704-1719. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.12.641

6

Hopkins C. Management of new onset loss of sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic - BRS Consensus Guidelines. Clin Otolaryngol. 2021

Jan;46(1):16-22. doi: 10.1111/coa.13636.

8

AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM DYSREGULATION

This provides suggestions as you engage in shared health care decision-making with Veterans. It is not intended to

replace clinical judgement.

Autonomic nervous system dysregulation may be present even after mild cases of COVID-19. Up to 48% of patients

reported dizziness or light headedness greater than 4 weeks post-COVID-19.

7

(NICE, 2021) Of 180 post-COVID-19

patients, 7.2% experienced dizziness and 61% of patients had autonomic dysfunction.

8

(Stella A, 2022)

Things to Keep in Mind

Signs and symptoms may manifest as palpitations, lightheadedness, dizziness, fatigue, blurry vision, falling,

presyncope and decreased exercise tolerance

Consider systemic conditions such as deconditioning, dehydration, anemia, hypoxia, anxiety, Parkinson’s Disease,

persistent fever, lung disease, and cardiac disease, including sinus node dysfunction, myocarditis, and heart failure

Consider orthostatic hypotension versus orthostatic tachycardia

Review medications such as diuretics, antidepressants, certain beta blockers

Assess pregnancy/lactation status, review teratogenic medications

Evaluation

Labs to Consider

Tests to Consider

Comprehensive

Metabolic Panel

(CMP)

Glucose

(hypoglycemia)

Complete Blood

Count (CBC)

(anemia)

Electrocardiogram (EKG) (arrythmia)

Evaluate for orthostatic blood pressure (lying, standing) for up to 10 minutes:

• Have patient lie down for 5 minutes and then measure blood pressure (BP) and

heart rate (HR). Have patient stand up and measure BP and HR after every 2

minutes for 10 minutes

• If there is a drop of systolic blood pressure (SBP) by 20 points or diastolic blood

pressure (DBP) by 10 points, then it is considered positive for orthostatic

hypotension

• If the HR increases by >30 BPM without hypotension, then it is positive for

orthostatic tachycardia

PACT Management to Consider

Consults to Consider

ICD-10 Code: U09.9, Post-COVID-19 condition, unspecified

Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 and Cardiovascular Autonomic Dysfunction:

What Do We Know?

Consider using Composite Autonomic Symptom Score (COMPASS 31)

9

(Sletten DM, 2012) for evaluating symptom trends (Appendix D)

Hydration immediately; for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)

consider 64 ounces of water intake daily

Avoid or limit alcohol intake as it can worsen or precipitate orthostatic

hypotension

Use of salt with caution especially if there is history of left ventricular

dysfunction (LVD); POTS recommendation is 3000-5000 mg per day

Avoid strenuous activity in hot weather

Start with recumbent or semi-recumbent exercise (rowing, swimming, cycling)

with gradual transition to upright exercise (walking, jogging, elliptical) as

orthostatic intolerance improves

Titrated return to activity program (Appendix B)

Lifestyle modification including slowly getting out of bed before standing and

use of compression stockings

Frequent, small, balanced meals with whole foods, protein, vegetables, and

fruits, and high fiber for POTS

Biofeedback

Cardiology:

• If assessment is

negative but high

clinical suspicion for

POTS

Physical Therapy:

• Titrated return to

individualized activity

program (Appendix B)

and energy

conservation

techniques

Occupational Therapy:

• Energy conservation

techniques

• Activities of daily

living (ADLs)

Whole Health System

approach:

• Biofeedback, yoga,

health coaching

Nutrition

7

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) UK, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188

8

Stella A. Autonomic dysfunction in post-COVID patients with and without neurological symptoms: a prospective multidomain observational study. Journal of

Neurology. 2022 Feb;269(2):587-596. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10735-y

9

Sletten DM. COMPASS 31: a refined and abbreviated Composite Autonomic Symptom Score. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Dec;87(12):1196-201. doi:

10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.013. PMID: 23218087; PMCID: PMC3541923

9

CHEST PAIN

This provides suggestions as you engage in shared health care decision-making with Veterans. It is not

intended to replace clinical judgement.

Chest pain is a common symptom with almost 5% of those diagnosed with COVID-19 reporting chest pain

>12 weeks after initial illness.

10

(Whitaker M, 2022) The usual conditions are considered in the differential for

recurrent chest pain.

11

(Gluckman T, 2022) In particular after COVID-19, cardiovascular conditions

including myocardial infarction (MI) and myocarditis were noted to be higher compared to those without

COVID-19, even in younger patients.

12

(Xie Y, 2022) The reason is unclear but may be related to virally

mediated vascular endothelial injury or indirectly from the immune response.

13

(Bellan M, 2021)

Furthermore, there seems to be a number of people with atypical chest pain that may be part of a post-

COVID-19 pain syndrome.

Things to Keep in Mind

The evaluation is similar to routine evaluation for chest pain

Maintain a high degree of suspicion for coronary artery disease (CAD), myocarditis/pericarditis, and

venous thromboembolism (VTE) given elevated risk after COVID-19 infection

Assess pregnancy/lactation status, review teratogenic medications

Evaluation

Labs to Consider

Tests to Consider

None

Additional testing as indicated by history and

exam

PACT Management to Consider

Consults to Consider

ICD-10 Code: U09.9, Post-COVID-19

condition, unspecified

For pleuritic pain or costochondritis:

• Diaphragmatic breathing

• Stretching

• 1 or 2 weeks of low dose non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID)

• If signs and symptoms worsen,

consider gastrointestinal causes like

esophagitis or esophageal spasm

Cardiology: if no improvement with initial therapies

described, or concern for underlying cardiac

disease or complications (myocarditis, heart

failure, ischemia/CAD, arrhythmia)

Physical Therapy: for accessory muscle usage/rib

excursion after ruling out cardiac issues

Chiropractic Care

Whole Health System approach: health coaching,

acupuncture

10

Whitaker M. Persistent COVID-19 symptoms in a community study of 606,434 people in England. Nature Communications 13, 1957 (2022).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29521-z

11

Gluckman T. 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Cardiovascular Sequelae of COVID-19 in Adults: Myocarditis and Other Myocardial

Involvement, Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Return to Play. J American College Cardiology. 2022 May, 79 (17) 1717–1756.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.02.003

12

Xie Y. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nature Medicine 28, 583–590 (2022).https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3

13

Bellan M. Respiratory and Psychophysical Sequelae Among Patients With COVID-19 Four Months After Hospital Discharge. JAMA Network Open.

2021;4(1):e2036142. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36142

10

COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

This provides suggestions as you engage in shared health care decision-making with Veterans. It is not intended to

replace clinical judgement.

Cognitive impairment is found in up to 60% of patients greater than 4 weeks after COVID-19. In some studies, 23% of

patients reported persistent signs and symptoms more than 8 months after COVID-19.

14

(NICE, 2021)

Things to Keep in Mind

Patient signs and symptoms

15

(AAPM&R, 2022)

• Attention - Brain fog, lost train of thought, concentration problems

• Processing Speed - Slowed thoughts

• Motor Function - Slowed movements

• Language - Word finding problems, reduced fluency

• Memory - Poor recall, forgetting tasks

• Mental Fatigue - Exhaustion, brain fog

• Executive Function - Poor multitasking and/or planning

• Visuospatial - Blurred vision, neglect

Perform a workup aiming to address reversible causes of dementia or cognitive impairment

Consider screenings for mental health, substance use and sleep disturbances

Assess pregnancy/lactation status, review teratogenic medications

Evaluation

Labs to Consider

Tests to Consider

B12

Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)

Glucose

Rapid plasma reagin (RPR)

For purely cognitive impairment without other

neurologic signs and symptoms, magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) or head computed

tomography (CT) is not routinely indicated

PACT Management to

Consider

Consults to Consider

ICD-10 Code: U09.9, Post-

COVID-19 condition,

unspecified

Medication reconciliation

Diaphragmatic breathing

Occupational Therapy, Speech Language Pathology or Primary Care

Mental Health Integration (PCMHI): perform Montreal Cognitive

Assessment (MOCA), Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), or Saint

Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS)

Occupational Therapy and Speech Language Pathology: perform

cognitive assessment, cognitive rehabilitation, functional assessment

and evaluate impact upon activities of daily living (ADLs), work,

school, and hobbies

PCMHI: address mental health concerns associated with coping with

new signs and symptoms, and provide cognitive behavioral therapy

for insomnia (CBT-I)

Nutrition: Nutrition optimization, food diary, and glucose regulation

Whole Health System approach: mindfulness/meditation, Tai Chi,

acupuncture, health coaching

Neurology: At initial visit if there are focal signs and symptoms or “red

flags” to suggest a systemic disease, OR potentially after 12-24

weeks if signs and symptoms worsen or persist, affecting daily

function and quality of life despite cognitive rehabilitation

14

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) UK, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188

15

American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. https://www.aapmr.org/members-publications/covid-19/pasc-guidance

11

COUGH

This provides suggestions as you engage in shared health care decision-making with Veterans. It is not

intended to replace clinical judgement.

Cough appears to be more common and duration may be longer after COVID-19.

16

(NICE, 2021) Cough

often persists for weeks to months after resolution of initial illness with 5-30% of patients reporting cough at 3

months.

17

(Jutant EM, 2022)

18

(Goërtz YMJ, 2020) There are likely multiple reasons potentially related to

development of fibrosis and underlying conditions such as asthma. For many people the cause is a post-

infectious cough, which is often managed like cough-variant asthma. The evaluation will be similar to

subacute and chronic cough for which the typical time courses are 3-8 weeks and >8 weeks, respectively.

Things to Keep in Mind

Post-infectious cough is likely a common cause which means it should resolve with time

Worsening cough could suggest secondary bacterial pneumonia or organizing pneumonia, which are

uncommon, so always correlate with dyspnea and hypoxia

Assess classic contributors such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), post-nasal drip, and

pulmonary fibrosis

Assess pregnancy/lactation status, review teratogenic medications

Evaluation

Labs to Consider

Tests to Consider

None

If greater than 8 weeks post COVID-19,

consider:

• Chest X-Ray

• Pulmonary Function Test (including pre-/post-

bronchodilator)

• Chest CT

PACT Management to Consider

Consults to Consider

ICD-10 Code: U09.9, Post-COVID-19 condition,

unspecified

Medication reconciliation to rule out iatrogenic causes

such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

(ACE-i)

Similar to cough-variant asthma with albuterol as

needed, inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), and ICS/long-

acting beta-agonist (LABA) for progressively severe or

more frequent episodes

Should limit to 2–3-month empiric trial and re-evaluate

if not resolved

Sputum management using hydration, expectorants,

and airway clearance devices

Diaphragmatic Breathing

Pulmonary: if continued cough

>12 weeks despite initial

treatment

Whole Health System approach:

biofeedback, mind body skills,

health coaching, yoga, Tai Chi

16

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) UK, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188

17

Jutant EM. Respiratory symptoms and radiological findings in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. ERJ Open Res 2022;8. 10.1183/23120541.00479-

2021

18

Goërtz YMJ. Persistent symptoms 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 infection: the post-COVID-19 syndrome? ERJ Open Res. 2020 Oct 26;6(4). doi:

10.1183/23120541.00542-2020.

12

DYSPNEA

This provides suggestions as you engage in shared health care decision-making with Veterans. It is not intended to

replace clinical judgement.

Post-COVID-19 dyspnea is common with multiple etiologies including cardiac, pulmonary, and neuromuscular issues.

Prevalence is likely proportional to initial severity with dyspnea reported in ~5-10% of mild (outpatient) cases,

19

(Sudre

CH, 2021)

20

(Nehme M, 2021) but up to 15-50% of those hospitalized.

21

(Carfi A, 2020)

22

(Froidure A, 2021)

23

(Jutant

EM, 2022) Patients who initially had mild COVID-19, and did not experience hypoxemia or require hospitalization, are

less likely to have post-acute pulmonary function or imaging abnormalities.

24

(AAPM&R, 2022)

Things to Keep in Mind

A functional assessment evaluating ADLs and recovery time after activity is helpful for triaging severity and creating

a titrated return to individualized activity program (Appendix B)

Differentiate between dyspnea at rest (forgetting to breathe), dyspnea with movement (bending forward), dyspnea

with exertion with or without hypoxemia, and post-exertional malaise (disproportionately long recovery time after

exertion)

Consider evaluation for pulmonary embolism (PE)

25

(Li P, 2021), coronary artery disease (CAD)

26

(Xie Y, 2022),

interstitial lung disease and myocarditis

27

(Puntmann VO, 2020)

28

(Daniels CJ, 2021) if clinically indicated given

higher rates after COVID-19

Assess pregnancy/lactation status, review teratogenic medications

Evaluation

Labs to Consider

Tests to Consider

Complete blood count (CBC)

If on oral contraceptive pill (OCP) with relevant

Wells or modified Geneva score, consider D-dimer

to screen for pulmonary thrombosis

Troponin if suspicious for myocarditis

Assess oxygen saturation at rest and with exertion

If lasting more than 8 weeks, consider:

• 2-view chest x-ray (CXR)

• Electrocardiogram (EKG)

• Pulmonary function tests (PFT)

PACT Management to Consider

Consults to Consider

ICD-10 Code: U09.9, Post-COVID-19

condition, unspecified

Supplemental oxygen

Pharmacologic therapies, including oral

corticosteroids, inhaled bronchodilators,

and inhaled corticosteroids, are not

routinely recommended for breathing

discomfort in the absence of a specific

diagnosis such as asthma

Heart healthy diet

Stress management

Diaphragmatic Breathing

Pulmonary: Persistent hypoxia at 6 weeks or abnormal work-up;

otherwise >12 weeks with persistent symptoms

Cardiology: Abnormal EKG, stress test, or highly suspicious for

cardiac etiology

Pulmonary rehabilitation: After prerequisite clinical assessment

for CAD, hypoxia, and participation (orthostatic hypotension)

while excluding post-exertional malaise

Ear, Nose, Throat (ENT) or Speech Language Pathology:

concurrent dysphonia or dysphagia

Physical Therapy: titrated return to individualized activity

program (Appendix B) if no post-exertional malaise

Occupational Therapy: regulated breathing during daily task

engagement in home and the community

Whole Health System approach: health coaching

19

Sudre CH. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nature Medicine. 2021 Apr;27(4):626-631. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y

20

Nehme M, CoviCare Study T. Prevalence of Symptoms More Than Seven Months After Diagnosis of Symptomatic COVID-19 in an Outpatient Setting. Annals

of Internal Medicine 2021;174:1252-60. doi: 10.7326/M21-0878.

21

Carfi A. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020;324:603-5.

22

Froidure A, Mahsouli A, Liistro G, et al. Integrative respiratory follow-up of severe COVID-19 reveals common functional and lung imaging sequelae.

Respiratory Medicine 2021;181:106383. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106383.

23

Jutant EM. Respiratory symptoms and radiological findings in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. European Respiratory Journal Open Res 2022;8 (2):00479-

2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00479-2021.

24

American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R). https://www.aapmr.org/members-publications/covid-19/pasc-guidance

25

Li P. Factors Associated With Risk of Postdischarge Thrombosis in Patients With COVID-19. JAMA Network Open. 2021 Nov 1;4(11):e2135397. doi:

10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.35397

26

Xie Y. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med 28, 583–590 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3

27

Puntmann VO. Outcomes of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).

JAMA Cardiology. 2020 Nov 1;5(11):1265-1273. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557

28

Daniels CJ. Prevalence of Clinical and Subclinical Myocarditis in Competitive Athletes With Recent SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Results From the Big Ten COVID-

19 Cardiac Registry. JAMA Cardiology. 2021;6(9):1078–1087. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2065

13

FATIGUE AND ACTIVITY INTOLERANCE

This provides suggestions as you engage in shared health care decision-making with Veterans. It is not intended

to replace clinical judgement.

Fatigue is one of the most common Long COVID related signs and symptoms in multiple studies, with an

incidence of 63% in those hospitalized

29

(AAPM&R, 2022) and 46% in those not hospitalized.

30

(Stavem K, 2021)

Things to Keep in Mind

Assess the Veteran’s prior level of function (independence with activities of daily living (ADLs), working

hobbies, exercising), current level of function, and recovery time from activities

Veteran may experience post-exertional malaise, making a titrated return to individualized activity (Appendix

B) important

Screen for mental health, substance disorder, sleep disturbances

Medication reconciliation

Women more likely to experience fatigue at 6 months

31

(Xiong Q, 2021)

Assess pregnancy/lactation status, review teratogenic medications

Evaluation

Labs to Consider

Tests to Consider

Complete blood count (CBC)

Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)

B12

Vitamin D

Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP)

Hemoglobin A1C

Consider:

• Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

• Hepatitis C virus (HCV)

Ambulatory pulse oximetry

30 second sit to stand to evaluate functional

lower extremity strength and endurance, and

provide information about fall risk, activity

tolerance, activity endurance, and functional

mobility (Appendix C)

29

(AAPM&R, 2022)

Evaluate other organ systems that may have

been affected by COVID-19 that impact exercise

participation (e.g., cardiac, pulmonary)

PACT Management to Consider

Consults to Consider

ICD-10 Code: U09.9, Post-COVID-19

condition, unspecified

Titrated return to individualized activity

program (Appendix B)

Diaphragmatic Breathing

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for

Insomnia

Replete B12 if low

Replete Vitamin D if low

Consider Fish oil – 1000mg (500mg

DHA/EPA) capsule combined

eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and

docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) daily with food

(avoid if on blood thinners or experiencing

gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD))

Occupational Therapy for a titrated return to

individualized activity program (Appendix B) and

energy conservation techniques

Physical Therapy for titrated return to individualized

activity program (Appendix B)

Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation (PM&R)

Cardiology

Pulmonology

Mental Health

Nutrition to discuss an anti-inflammatory lifestyle

and diet history.

Whole Health System approach: mindfulness,

health coaching, yoga, Tai Chi, biofeedback

29

American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R). https://www.aapmr.org/members-publications/covid-19/pasc-guidance

30

Stavem K. Prevalence and Determinants of Fatigue after COVID-19 in Non-Hospitalized Subjects: A Population-Based Study. Int J Environ Res Public

Health. 2021 Feb 19;18(4):2030. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042030

31

Xiong Q. Clinical sequelae of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China: a single-centre longitudinal study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021 Jan;27(1):89-95. doi:

10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.023

14

HEADACHES

This provides suggestions as you engage in shared health care decision-making with Veterans. It is not

intended to replace clinical judgement.

Up to 79% of patients reported headache at greater than 4 weeks post-COVID-19

32

(NICE, 2022), though

this improved with time and 10.6% reported ongoing headaches at 90 days, and 8.4% ≥180 days after

symptom onset/hospital discharge.

33

(Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, 2021)

Things to Keep in Mind

Consider screening for mental health, substance use disorder, sleep disturbances, traumatic brain

injury (TBI)

Neurological examination warranted

Medication reconciliation

Consider the following:

• Pre-COVID-19 episodic migraine now chronic post-COVID-19

• Delayed onset COVID-19 headache

• Persistent headache with migraine features onset with COVID-19

• Sinus congestion

• Cervical and upper back muscle tightness

• Increased stress level

• Medication rebound headache

Assess pregnancy/lactation status, review teratogenic medications

Evaluation

Labs to Consider

Tests to Consider

None

No recommendations for imaging if headache only

PACT Management to Consider

Consults to Consider

ICD-10 Code: U09.9, Post-COVID-19 condition,

unspecified

Treating Headaches Handout for Patients

Over the counter (OTC) and prescription

analgesic review

Lifestyle management and evaluation (sleep,

exercise, nutrition, headache diary)

Consider Riboflavin 400mg every morning with

food

Consider Magnesium Oxide 420mg every

evening

Regulate glucose levels

Recommend 64 ounces of water daily

Diaphragmatic Breathing

Neurology: if no improvement despite

initial management or if abnormal

neurological examination present

Nutrition: to discuss an anti-

inflammatory diet and headache

elimination diet

Whole Health System approach:

biofeedback, mindfulness, health

coaching, yoga, acupuncture, Tai Chi

Chiropractic Care

Osteopathy

32

NICE https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188/resources/covid19-rapid-guideline-managing-the-longterm-effects-of-covid19-pdf-51035515742

33

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C. Headache as an acute and post-COVID-19 symptom in COVID-19 survivors: A meta-analysis of the current literature.

Eur J Neurol. 2021 Nov;28(11):3820-3825. doi: 10.1111/ene.15040.

15

MENTAL HEALTH (ANXIETY, DEPRESSION, PTSD)

This provides suggestions as you engage in shared health care decision-making with Veterans. It is not

intended to replace clinical judgement.

Anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been reported in 30 -

40% of COVID-19 survivors, similar to survivors of other pathogenic coronaviruses.

34

(Nalbandian A, 2021)

These signs and symptoms may be exacerbated by specific COVID-19 related or pandemic-associated events

such as loneliness, job loss, childcare issues, lack of typical recreational activities, and relationship strain.

Things to Keep in Mind

Given the overall increase in suicides during the pandemic and the increased risk for mental health

symptoms following COVID-19, consider assessment for suicidality

Complete usual mental health screens and discern whether reported signs and symptoms are temporally

related to Long COVID (increase in previous or new signs and symptoms)

Normalize and validate signs and symptoms as appropriate

Assess contribution from sleep disturbances, physical function changes, substance use, and other lifestyle

changes that may affect mental health

Consider the following:

• Adjustment Disorder following change in health or role

• Generalized Anxiety Disorder

• Panic Disorder

• Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

• Depression

• Anxiety related to air hunger

• Acute Stress Disorder

• Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

• Post Intensive Care Syndrome

• Sleep Disorders to include insomnia

• Substance Use Disorder

• Coping with stigma

• Survivor’s guilt

• Problems in relationship

Assess pregnancy/lactation status, review teratogenic medications

Evaluation

Labs to Consider

Tests to Consider

Routine labs for mental health evaluation

None

PACT Management to Consider

Consults to Consider

ICD-10 Code: U09.9, Post-COVID-19 condition, unspecified

Explore Veteran’s hope to address signs and symptoms using

Veteran's mission, aspiration, and purpose.

Primary Care Mental Health Integration (PCMHI)

Veterans Crisis Line – contact options:

• Dial 988 then Press 1

• Dial 800-273-8255 then press 1

• Text 838255

COVID-19 Coach App – Stress management

Insomnia Coach App - Path to better sleep

Diaphragmatic Breathing

Guided Meditation – Audio files

Consider antidepressant

Consider Fish oil – 1000mg (500mg DHA/EPA) capsule

combined eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic

acid (DHA) daily with food (avoid if on blood thinners or

experiencing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD))

Explore interest in Mental Health

follow up

• Mental Health consult for

high complexity

Long COVID Support Groups

Nutrition

Physical Therapy: titrated return

to individualized activity program

(Appendix B)

Peer Support Specialists

Whole Health System approach:

health coach, Tai Chi, yoga,

acupuncture/battlefield

acupuncture/national

acupuncture detox

Chaplain

34

Nalbandian A. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021 Apr;27(4):601-615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z

16

OTHER POTENTIAL CONDITIONS:

CARDIOMETABOLIC AND AUTOIMMUNE

This provides suggestions as you engage in shared health care decision-making with Veterans. It is not intended to replace

clinical judgement.

Given evidence that COVID-19 may increase the risk for Diabetes, renal impairment, cardiovascular complications and

autoimmune conditions, a history of infection should be considered along with other factors in deciding who should be

screened for these conditions.

Cardiovascular

Increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI),

cardiovascular accident (CVA), congestive heart

failure (CHF), myocarditis

35

(Xie Y, 2022)

High awareness for cardiovascular complications

36

(Gluckman T, 2022)

Kidney Disease

Increased risk of significant decline in estimated

glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), proportional to

severity of disease, though present even in those

not admitted to the hospital

37

(Bowe B, 2021)

If not already assessed, evaluate kidney function glomerular

filtration rate (GFR) using creatine or cystatin C at 3-6

months after resolution of COVID-19

Compare results to pre-COVID-19 GFR if available

Diabetes

Compared with those who never had COVID-19,

Veterans who have had COVID-19 are at greater

risk of developing type 2 Diabetes up to a year later,

even after a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection.

38

(Xie Y,

2022)

39

(Wander P, 2022)

Ask all Veterans who had severe COVID-19 about signs and

symptoms of diabetes at every routine visit. Consider asking

Veterans who had mild or asymptomatic COVID-19.

A baseline A1c test should be done post-COVID-19 for all

Veterans

For symptomatic Veterans:

• Veterans experiencing post-COVID-19 signs and

symptoms with pre-existing diabetes should have an

additional A1c test at 6 months post-infection

• Veterans experiencing post-COVID-19 signs and

symptoms without pre-diabetes but with significant risk

factors for diabetes- such as strong family history and

obesity-can be considered for an A1c test at 6 months

post-infection

• Routine laboratory testing for other indications should

include a Fasting Blood Glucose (FBS) when possible

• If there has been a significant increase (>0.5%) in A1c

from baseline, obtain a repeat A1c or FBS earlier than 6

months post-infection

Autoimmune

Up to 25% may develop antinuclear antibody (ANA)

positivity, but the titers were low and deemed not

clinically significant.

40

(Lerma L, 2020) The serology

of 61 patients 5 weeks after COVID-19 had no

increased incidence of anti-cyclic citrullinated

peptides (CCP) positivity.

41

(Derksen V, 2021)

Coronaviruses seem to typically cause signs and symptoms

of arthralgia and myalgia.

42

(Zacharias H, 2021)

43

(Cui D,

2022) If a patient develops clinical features of inflammatory

arthritis following COVID-19, the diagnostic work-up should

be similar to a patient with new onset rheumatoid arthritis

(RA) in an infection naive patient.

44

(Sapkota H, 2022)

35

Xie Y. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med 28, 583–590 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3

36

Gluckman. ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Cardiovascular Sequelae of COVID-19 in Adults, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.02.003

37

Bowe B. JASN November 2021, 32 (11) 2851-2862; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2021060734

38

Xie Y. Risks and burdens of incident diabetes in long COVID: a cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022 May;10(5):311-321. doi: 10.1016/S2213-

8587(22)00044-4

39

Wander P. The Incidence of Diabetes Among 2,777,768 Veterans with and Without Recent SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Diabetes Care 1 April 2022; 45 (4): 782–788.

https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-1686

40

Lerma L. Prevalence of autoantibody responses in acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Transl Autoimmun, 2020. 10.1016/j.jtauto.2020.100073

41

Derksen V. Onset of rheumatoid arthritis after COVID-19: coincidence or connected? Ann Rheum Dis, 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-219859

42

Zacharias H. Rheumatological complications of Covid 19. Autoimmun Rev, 2021. 20(9): 10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102883

43

Cui D. Rheumatic Symptoms Following Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Chronic Post–COVID-19 Condition, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume

9, Issue 6, June 2022, ofac170, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofac170

44

Sapkota H. Long COVID from rheumatology perspective - a narrative review. Clin Rheumatol, 2022. 41(2): p. 337-348. 10.1007/s10067-021-06001-1

Epidemiology

Recommendation

17

APPENDIX A: OLFACTORY TRAINING

This section provides details about the Olfactory Training at the Veterans Affairs Otolaryngology

Department in Atlanta, GA

1. Actively smell or sniff

2. Four familiar scents

3. Think about your memory of the odor while smelling the odor

4. In random order, sniff for a total of 20-60 seconds for each odor

5. Rest for 30 seconds between each scent

6. Sniff the four scents, 2 to 4 times a day, each, for 24-36 weeks

7. Change the odorants used every 12 weeks

The stimulating smells used are often in commercially available smell kits are often selected from major

smell categories, such as aromatic, flowery, fruity, and resinous.

18

APPENDIX B: FATIGUE AND ACTIVITY INTOLERANCE

This section provides details on the titrated return to individualized activity program including baseline

activity tolerance and paced graded activity.

Titrated Return to Individualized Activity Program

Mild Fatigue: Patients should try to continue all household and community activities that have been

tolerated with a slow return to higher intensity activities and exercise. The “rule of tens” may be helpful.

Moderate Fatigue: It’s recommended to continue household and limited community activities that have

been tolerated. Patients should begin an activity or aerobic exercise program with exertion at sub-

maximal levels (rate of perceived exertion (RPE) 9–11/Very Light-Light).

Severe Fatigue: Severe fatigue or significant post-exertional malaise: Continue any house-hold

activities that have been tolerated without symptom exacerbation. Patients can begin a physical activity

program, which should initially consist of upper and lower extremity stretching and light muscle

strengthening before any targeted aerobic activity. Once tolerated, patients can begin an activity or

aerobic exercise program at submaximal levels, RPE 7–9/Extremely to Very Light.

Activities or exercise can be slowly advanced as the patient tolerates in all levels of fatigue. Harm can

be done if patients are pushed beyond what they can tolerate. If signs and symptoms worsen after

increasing activity level in any severity of fatigue (which may be delayed until the evening and/or days

after the activity/exercise session), patient should return to prior tolerated level of activity.

Baseline Activity Tolerance

Measure how long low intensity tasks such as walking, light exercises, and daily activities (e.g., self-

care tasks, light housework) can be engaged in without resulting in immediate or delayed fatigue. Do

this for both “good” and “bad” days for 3 days. Average the three trials and subtract a fifth. The result

with be your activity duration starting point.

Table 1: Activity Duration Baseline

Time 1

Time 2

Time 3

Average

4/5 Average

19 min

17 min

21 min

19 min

15 min

Paced Graded Activity

Start with low intensity daily activities. Keep in mind that patients with different symptom severity will be

able to tolerate different levels of activity. Transition over the course of days to months based on

response, with a 10-20% increase every 1-2 weeks being a common marker. Work to keep a consistent

schedule vs adapting day by day based on symptom levels or life demands. It is important to remember

to not try to over-exert oneself on days they are feeling well, as this may worsen signs and symptoms.

To increase activity level over time:

1. First focus on increasing the FREQUENCY of activity

2. Then work to increase the DURATION of activity

3. When able to engage reliably in low intensity activity consistently throughout the day without

flares of fatigue, then moderate and eventually higher INTENSITY activity can be added.

19

The following table gives an example of what this could look like in practice. Help your Veteran to set

their own starting point and progression based on their activity tolerance and response.

Table 2: Pace Graded Activity

Week

Intensity

Activity Duration (min)

Rest Duration (min)

1-2

Low

15

50

3-4

Low

15

40

5-6

Low

15

30

7-8

Low

20

30

9-10

Low

25

25

11-12

Low

30

20

13-14

Low

35

15

15-16

Low ; Moderate

30 ; 5

15

17-18

Low ; Moderate

25 ; 10

15

19-20

Low ; Moderate

20; 15

15

20

APPENDIX C: 30 SECOND SIT TO STAND TEST

The 30 second chair stand test (30CST) is a measurement that assess functional lower extremity

strength in older adults. It is part of the Fullerton Functional Fitness Test Battery. This test was

developed to overcome the floor effect of the 5 or 10 repetition sit to stand test in older adults.

Instructions

1. Instruct the patient:

a. Sit in the middle of the chair.

b. Place your hands on the opposite shoulder crossed, at the wrists.

c. Keep your feet flat on the floor.

d. Keep your back straight and keep your arms against your chest.

e. On “Go,” rise to a full standing position, then sit back down again.

f. Repeat this for 30 seconds.

2. On the word “Go,” begin timing. If the patient must use their arms to stand, stop the test. Record

“0” for the number and score.

3. Count the number of times the patient comes to a full standing position in 30 seconds. If the

patient is over halfway to a standing position when 30 seconds have elapsed, count it as a

stand.

4. Record the number of times the patient stands in 30 seconds.

21

APPENDIX D: COMPOSITE AUTONOMIC SYMPTOM

SCORE (COMPASS 31)

COMPASS 31 is a quantitative measure of autonomic symptoms.

Assessment

1. In the past year, have you ever felt faint, dizzy, “goofy”, or had difficulty thinking soon after standing

up from a sitting or lying position?

1 Yes

2 No (if you marked No, please skip to question 5)

2. When standing up, how frequently do you get these feelings or symptoms?

1 Rarely

2 Occasionally

3 Frequently

4 Almost Always

3. How would you rate the severity of these feelings or symptoms?

1 Mild

2 Moderate

3 Severe

4. In the past year, have these feelings or symptoms that you have experienced:

1 Gotten much worse

2 Gotten somewhat worse

3 Stayed about the same

4 Gotten somewhat better

5 Gotten much better

6 Completely gone

5. In the past year, have you ever noticed color changes in your skin, such as red, white, or purple?

1 Yes

2 No (if you marked No, please skip to question 8)

6. What parts of your body are affected by these color changes? (Check all that apply)

1 Hands

2 Feet

7. Are these changes in your skin color:

1 Getting much worse

2 Getting somewhat worse

3 Staying about the same

4 Getting somewhat better

5 Getting much better

6 Completely gone

8. In the past 5 years, what changes, if any, have occurred in your general body sweating?

1 I sweat much more than I used to

2 I sweat somewhat more than I used to

3 I haven’t noticed any changes in my sweating

4 I sweat somewhat less than I used to

5 I sweat much less than I used to

22

9. Do your eyes feel excessively dry?

1 Yes

2 No

10. Does your mouth feel excessively dry?

1 Yes

2 No

11. For the symptom of dry eyes or dry mouth that you have had for the longest period of time, is this

symptom:

1 I have not had any of these symptoms

2 Getting much worse

3 Getting somewhat worse

4 Staying about the same

5 Getting somewhat better

6 Getting much better

7 Completely gone

12. In the past year, have you noticed any changes in how quickly you get full when eating a meal?

1 I get full a lot more quickly now than I used to

2 I get full more quickly now than I used to

3 I haven’t noticed any change

4 I get full less quickly now than I used to

5 I get full a lot less quickly now than I used to

13. In the past year, have you felt excessively full or persistently full (bloated feeling) after a meal?

1 Never

2 Sometimes

3 A lot of the time

14. In the past year, have you vomited after a meal?

1 Never

2 Sometimes

3 A lot of the time

15. In the past year, have you had a cramping or colicky abdominal pain?

1 Never

2 Sometimes

3 A lot of the time

16. In the past year, have you had any bouts of diarrhea?

1 Yes

2 No (if you marked No, please skip to question 20)

17. How frequently does this occur?

1 Rarely

2 Occasionally

3 Frequently ____________ times per month

4 Constantly

18. How severe are these bouts of diarrhea?

1 Mild

2 Moderate

3 Severe

23

19. Are your bouts of diarrhea getting:

1 Much worse

2 Somewhat worse

3 Staying the same

4 Somewhat better

5 Much better

6 Completely gone

20. In the past year, have you been constipated?

1 Yes

2 No (if you marked No, please skip to question 24)

21. How frequently are you constipated?

1 Rarely

2 Occasionally

3 Frequently ____________ times per month

4 Constantly

22. How severe are these episodes of constipation?

1 Mild

2 Moderate

3 Severe

23. Is your constipation getting:

1 Much worse

2 Somewhat worse

3 Staying the same

4 Somewhat better

5 Much better

6 Completely gone

24. In the past year, have you ever lost control of your bladder function?

1 Never

2 Occasionally

3 Frequently ____________ times per month

4 Constantly

25. In the past year, have you had difficulty passing urine?

1 Never

2 Occasionally

3 Frequently ____________ times per month

4 Constantly

26. In the past year, have you had trouble completely emptying your bladder?

1 Never

2 Occasionally

3 Frequently ____________ times per month

4 Constantly

27. In the past year, without sunglasses or tinted glasses, has bright light bothered your eyes?

1 Never (if you marked Never, please skip to question 29)

2 Occasionally

3 Frequently

4 Constantly

24

28. How severe is this sensitivity to bright light?

1 Mild

2 Moderate

3 Severe

29. In the past year, have you had trouble focusing your eyes?

1 Never (if you marked Never, please skip to question 31)

2 Occasionally

3 Frequently

4 Constantly

30. How severe is this focusing problem?

1 Mild

2 Moderate

3 Severe

31. Is the most troublesome symptom with your eyes (i.e. sensitivity to bright light or trouble focusing)

getting:

1 I have not had any of these symptoms

2 Much worse

3 Somewhat worse

4 Staying about the same

5 Somewhat better

6 Much better

7 Completely gone

25

Raw Domain Scoring

The raw domain scores are derived by adding the points for the questions comprising each domain.

Where an answer to a question is not assigned a point, the score for that answer is zero.

Final Domain Scoring

The final domain scores are generated by multiplying the raw score with a weight index. The total score

is the sum of all domain scores.

Domains and Number of Questions Retained Based on Exploratory Factor Analysis and Clinical

Revisions as Used in the Final Instrument (COMPASS 31)

a

Domain

No. of

Questions

Max raw score

Weighting

factor

Max weighted

score

Cronbach

α

Orthostatic Intolerance

4

10

4.0

40

0.92

Vasomotor

3

6

0.8333333

5

0.91

Secretomotor

4

7

2.1428571

15

0.48

Gastrointestinal

b

12

28

0.8928571

25

0.78

Bladder

3

9

1.1111111

10

0.62

Pupillomotor

5

15

0.3333333

5

0.84

Total

31

75

100

a

Appropriate weighting factors for each domain result in appropriately balanced autonomic domains

and a total score between 0 and 100. Max = maximum.

b

Combines former constipation, diarrhea, and gastroparesis domains into one domain.

26

RESOURCES

Veteran Whole Health Library

https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/

Veteran Whole Health Education Handouts

https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/veteran-handouts/index.asp

Veterans Health Library

www.veteranshealthlibrary.va.gov

Veterans Crisis Line

https://www.veteranscrisisline.net

American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R)

https://www.aapmr.org/members-publications/covid-19/pasc-guidance

https://www.aapmr.org/members-publications/icd-10-codes

National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

www.prevention.va.gov

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), UK

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188

UW Integrative Health, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health

https://www.fammed.wisc.edu/integrative/resources/

27

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

• Addison AB, Wong B, Ahmed T, Macchi A, Konstantinidis I, Huart C, et al. Clinical Olfactory

Working Group consensus statement on the treatment of postinfectious olfactory dysfunction. The

Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2021 May;147(5):1704-1719. doi:

10.1016/j.jaci.2020.12.641

• Alaparthi GK, Augustine AJ, Anand R, Mahale A. Comparison of Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercise,

Volume and Flow Incentive Spirometry, on Diaphragm Excursion and Pulmonary Function in

Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Minimally

Invasive Surgery. 2016;2016:1967532. doi: 10.1155/2016/1967532

• American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R) (2022). PASC Consensus

Guidance. https://www.aapmr.org/members-publications/covid-19/pasc-guidance

• Andres S, Pevny S, Ziegenhagen R, et al. Safety aspects of the use of quercetin as a dietary

supplement. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2018;62(1). doi:10.1002/mnfr.201700447

• Anton SD, Embry C, Marsiske M, et al. Safety and metabolic outcomes of resveratrol

supplementation in older adults: results of a twelve-week, placebo-controlled pilot study.

Experimental Gerontology. 2014;57:181-187. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2014.05.015

• Asadi-Pooya AA, Akbari A, Emami A, Lotfi M, Rostamihosseinkhani M, Nemati H, Barzegar Z,

Kabiri M, Zeraatpisheh Z, Farjoud-Kouhanjani M, Jafari A, Sasannia F, Ashrafi S, Nazeri M, Nasiri

S, Shahisavandi M. Risk Factors Associated with Long COVID Syndrome: A Retrospective Study.

Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2021 Nov;46(6):428-436. doi: 10.30476/ijms.2021.92080.2326

• Aziz M, Goyal H, Haghbin H, Lee-Smith WM, Gajendran M, Perisetti A. The Association of "Loss of

Smell" to COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of the Medical

Sciences. 2021 Feb;361(2):216-225. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2020.09.017

• Bellan M, Soddu D, Balbo PE, Baricich A, Zeppegno P, Avanzi GC, et al. Respiratory and

Psychophysical Sequelae Among Patients With COVID-19 Four Months After Hospital Discharge.

JAMA Network Open. 2021 Jan 4;4(1): doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36142

• Berman AY, Motechin RA, Wiesenfeld MY, Holz MK. The therapeutic potential of resveratrol: a

review of clinical trials. Precision Oncology - Nature. 2017;1:35. doi:10.1038/s41698-017-0038-6

• Bowe B, Xie Y, Xu E, Al-Aly Z. Kidney Outcomes in Long COVID. Journal of the American Society

of Nephrology. Nov 2021, 32 (11) 2851-2862; doi: 10.1681/ASN.2021060734

• Cavanaugh AM, Spicer KB, Thoroughman D, Glick C, Winter K. Reduced Risk of Reinfection with

SARS-CoV-2 After COVID-19 Vaccination — Kentucky, May–June 2021. Morbidity and Mortality

Weekly Report. 2021 Aug 13;70(32):1081-1083. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7032e1

• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions. July

11, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html

• Chainani-Wu N. Safety and anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin: a component of tumeric

(Curcuma longa). Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2003;9(1):161-168.

doi:10.1089/107555303321223035

• Cui D, Wang Y, Huang L, Gu X, Huang Z, Mu S, Wang C, Cao B. Rheumatic Symptoms Following

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Chronic Post–COVID-19 Condition, Open Forum

Infectious Diseases, Volume 9, Issue 6, June 2022, ofac170, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofac170

28

• Derksen VFAM, Kissel T, Lamers-Karnebeek FBG, et al. Onset of rheumatoid arthritis after COVID-

19: coincidence or connected? Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2021;80:1096-

1098.:http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-219859

• Douaud G, Lee S, Alfaro-Almagro F, Arthofer C, Wang C, McCarthy P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is

associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature. 2022 Apr;604(7907):697-707.

doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04569-5

• European Food Safety Authority, Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies, 2016.

Scientific opinion on the safety of synthetic trans-resveratrol as a novel food pursuant to Regulation

(EC) No 258/97. EFSA Journal 2016;14(1):4368, 30 pp. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4368

• Favero G, Franceschetti L, Bonomini F, Rodella LF, Rezzani R. Melatonin as an anti-inflammatory

agent modulating inflammasome activation. International Journal of Endocrinology.

2017;2017:1835195. doi:10.1155/2017/1835195

• Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Navarro-Santana M, Gómez-Mayordomo V, Cuadrado ML, García-

Azorín D, Arendt-Nielsen L, Plaza-Manzano G. Headache as an acute and post-COVID-19

symptom in COVID-19 survivors: A meta-analysis of the current literature. European Journal of

Neurology. 2021 Nov;28(11):3820-3825. doi: 10.1111/ene.15040

• Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Martín-Guerrero JD, Pellicer-Valero ÓJ, Navarro-Pardo E, Gómez-

Mayordomo V, Cuadrado ML, Arias-Navalón JA, Cigarán-Méndez M, Hernández-Barrera V, Arendt-

Nielsen L. Female Sex Is a Risk Factor Associated with Long-Term Post-COVID Related-

Symptoms but Not with COVID-19 Symptoms: The LONG-COVID-EXP-CM Multicenter Study.

Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022 Jan 14;11(2):413. doi: 10.3390/jcm11020413

• Gaudet T, Kligler B. Whole Health in the Whole System of the Veterans Administration: How Will

We Know We Have Reached This Future State? Journal of Alternative and Complementary

Medicine. 2019 Mar;25(S1):S7-S11. doi: 10.1089/acm.2018.29061.gau

• Gluckman TJ, Bhave NM, Allen LA, Chung EH, Spatz ES, Ammirati E, et al. 2022 ACC Expert

Consensus Decision Pathway on Cardiovascular Sequelae of COVID-19 in Adults: Myocarditis and

Other Myocardial Involvement, Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection, and Return to Play:

A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. Journal of the

American College of Cardiology. 2022 May 3;79(17):1717-1756. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.02.003

• Goërtz YMJ, Van Herck M, Delbressine JM, Vaes AW, Meys R, Machado FVC, et al. Persistent

symptoms 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 infection: the post-COVID-19 syndrome? European

Respiratory Society (ERS) Open Research. 2020 Oct 26;6(4):00542-2020.

doi:10.1183/23120541.00542-2020

• Hopkins C, Alanin M, Philpott C, et al. Management of new onset anosmia during the COVID

pandemic - BRS Consensus Guidelines. Authorea. May 22, 2020.

doi:10.22541/au.159015263.38072348

• Hu J, Webster D, Cao J, Shao A. The safety of green tea and green tea extract consumption in

adults – results of a systematic review. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2018;95:412-

433. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2018.03.019

• Hummel T, Heilmann S, Hüttenbriuk KB. Lipoic acid in the treatment of smell dysfunction following

viral infection of the upper respiratory tract. Laryngoscope. 2002 Nov;112(11):2076-80.

doi:10.1097/00005537-200211000-00031.

29

• Institute for Functional Medicine (IFM). COVID-19 Functional Medicine Resources: The Functional

Medicine Approach to COVID-19: Virus-Specific Nutraceutical and Botanical Agents. October 15,

2021. https://www.ifm.org/news-insights/the-functional-medicine-approach-to-COVID-19-virus-

specific-nutraceutical-and-botanical-agents/

• Isomura T, Suzuki S, Origasa H, et al. Liver-related safety assessment of green tea extracts in

humans: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Published correction appears in

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016;70(11):1340

• Jutant EM, Meyrignac O, Beurnier A, Jaïs X, Pham T, Morin L, et al. Respiratory symptoms and

radiological findings in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. European Respiratory Society (ERS) Open

Research. 2022 Apr 19;8(2):00479-2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00479-2021

• Kattar N, Do TM, Unis GD, Migneron MR, Thomas AJ, McCoul ED. Olfactory Training for Postviral

Olfactory Dysfunction: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck

Surgery. 2021 Feb;164(2):244-254. doi: 10.1177/0194599820943550

• Krejci, Laura P. MSW; Carter, Kennita MD; Gaudet, Tracy MD Whole Health, Medical Care:

December 2014 - Volume 52 - Issue - p S5-S8, doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000226

• Kronenbuerger M, Pilgramm M. Olfactory Training. StatPearls; January 3, 2022.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567741/

• Kunnumakkara AB, Bordoloi D, Padmavathi G, et al. Curcumin, the golden nutraceutical:

multitargeting for multiple chronic diseases. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2017;174(11):1325-

1348. doi:10.1111/bph.13621

• Leite Pacheco R, de Oliveira Cruz Latorraca C, Adriano Leal Freitas da Costa A, Luiza Cabrera

Martimbianco A, Vianna Pachito D, Riera R. Melatonin for preventing primary headache: a

systematic review. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2018;72 (7):e13203.

doi:10.1111/ijcp.13203

• Lerma LA, Chaudhary A, Bryan A, Morishima C, Wener MH, Fink SL. Prevalence of autoantibody

responses in acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Journal of Translational Autoimmunity.

2020;3:100073. doi: 10.1016/j.jtauto.2020.100073

• Mehrabani S, Askari G, Miraghajani M, Tavakoly R, Arab A. Effect of coenzyme Q10

supplementation on fatigue: A systematic review of interventional studies. Complementary

Therapies in Medicine. 2019 Apr;43:181-187. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.01.022

• McDermott MM, Leeuwenburgh C, Guralnik JM, et al. Effect of resveratrol on walking performance

in older people with peripheral artery disease: the RESTORE randomized clinical trial. JAMA

Cardiology. 2017;2(8):902-907. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0538

• Menegazzi M, Campagnari R, Bertoldi M, Crupi R, Di Paola R, Cuzzocrea S. Protective effect of

epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) in diseases with uncontrolled immune activation: could such a

scenario be helpful to counteract COVID-19? International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

2020;21(14):5171. doi:10.3390/ijms21145171

• Mytinger M, Nelson RK, Zuhl M. Exercise Prescription Guidelines for Cardiovascular Disease

Patients in the Absence of a Baseline Stress Test. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and

Disease. 2020 Apr 27;7(2):15. doi: 10.3390/jcdd7020015.

• Nalbandian, A., Sehgal, K., Gupta, A. et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nature Medicine 27,

601–615 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z

30

• National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the

longterm effects of COVID-19. January 3,2022.

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188/resources/covid19-rapid-guideline-managing-the-longterm-

effects-of-covid19-pdf-51035515742

• Oketch-Rabah HA, Roe AL, Rider CV, et al. United States Pharmacopeia (USP) comprehensive

review of the hepatotoxicity of green tea extracts. Toxicology reports. 2020;7:386-402.

doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.02.008

• Pelà G, Goldoni M, Solinas E, Cavalli C, Tagliaferri S, Ranzieri S, Frizzelli A, Marchi L, Mori PA,

Majori M, Aiello M, Corradi M, Chetta A. Sex-Related Differences in Long-COVID-19 Syndrome.

Journal of Womens Health (Larchmt). 2022 May;31(5):620-630. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2021.0411

• Premraj L, Kannapadi NV, Briggs J, Seal SM, Battaglini D, Fanning J, et al. Mid and long-term

neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome: A meta-analysis.

Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2022 Mar 15;434:120162. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2022.120162

• Saenger U, Fumal A, Magis D, Seidel L, Agosti RM, Schoenen J. Efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in

migraine prophylaxis: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2005 Feb 22;64(4):713-5. doi:

10.1212/01.WNL.0000151975.03598.ED

• Sapkota, H. a. (2022). Long COVID from rheumatology perspective - a narrative review. Clinical

Rheumatology, 41(2). doi:10.1007/s10067-021-06001-1

• Sarma DN, Barrett ML, Chavez ML, et al. Safety of green tea extracts: a systematic review by the

US Pharmacopeia. Drug Safety. 2008;31(6):469-484. doi:10.2165/00002018-200831060-00003

• Shoskes DA, Zeitlin SI, Shahed A, Rajfer J. Quercetin in men with category III chronic prostatitis: a

preliminary prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Urology. 1999;54(6):960-963.

doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00358-1

• Sletten DM, Suarez GA, Low PA, Mandrekar J, Singer W. COMPASS 31: a refined and abbreviated

Composite Autonomic Symptom Score. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2012 Dec;87(12):1196-201. doi:

10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.013

• Sorokowska A, Drechsler E, Karwowski M, Hummel T (March 2017). "Effects of olfactory training: a

meta-analysis". Rhinology. 55 (1): 17–26. doi:10.4193/Rhin16.195

• Stavem K, G. W. (2021, Feb 19). Prevalence and Determinants of Fatigue after COVID-19 in Non-

Hospitalized Subjects: A Population-Based Study. International Journal of Environmental Research

and Public Health, 18(4). doi:10.3390/ijerph18042030

• Stella, A. B., Furlanis, G., Frezza, N. A., Valentinotti, R., Ajcevic, M., & Manganotti, P. (2022).

Autonomic dysfunction in post-COVID patients with and without neurological symptoms: a

prospective multidomain observational study. Journal of Neurology, 269(2), 587-596.

doi:10.1007/s00415-021-10735-y

• Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations betweenCOVID-19 and

psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62,354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet

Psychiatry. 2021 Feb;8(2):130-140. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4

• Turner RS, Thomas RG, Craft S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of

resveratrol for Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2015;85(16):1383-1391.

doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002035

31

• Vehar S, Boushra M, Ntiamoah P, Biehl M. Update to post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2

infection: Caring for the 'long-haulers'. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2021 Oct 8. doi:

10.3949/ccjm.88a.21010-up

• Wander P, Lowy E, Beste LA, Tulloch-Palomino L, Korpak A, Peterson AC, et al. The Incidence of

Diabetes Among 2,777,768 Veterans With and Without Recent SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Diabetes

Care 1 April 2022; 45 (4): 782–788. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-1686

• Whitaker, M., Elliott, J., Chadeau-Hyam, M. et al. Persistent COVID-19 symptoms in a community

study of 606,434 people in England. Nature Communication 13, 1957 (2022).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29521-z

• Wirtz PH, Spillmann M, Bärtschi C, Ehlert U, von Känel R. Oral melatonin reduces blood

coagulation activity: a placebo-controlled study in healthy young men. Journal of Pineal Research.

2008;44(2):127-133. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00499.x

• Xie, Y., Bowe, B. & Al-Aly, Z. Burdens of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 by severity of acute

infection, demographics and health status. Nature Communication. 12, 6571 (2021).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26513-3