GAO

United States Government Accountabilit

y

Office

Report to the Committee on Homeland

Security and Governmental Affairs,

U.S. Senate

DCAA AUDITS

Widespread Problems

with Audit Quality

Require Significant

Reform

September 2009

GAO-09-468

What GAO Found

United States Government Accountability Office

Why GAO Did This Study

Highlights

Accountability Integrity Reliability

September 2009

DCAA AUDITS

Widespread Problems with Audit Quality Require

Significant Reform

Highlights of GAO-09-468, a report to the

Committee on Homeland Security and

Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate

The Defense Contract Audit

Agency (DCAA) under the

Department of Defense (DOD)

Comptroller plays a critical role in

contractor oversight by providing

auditing, accounting, and financial

advisory services in connection

with DOD and other federal agency

contracts and subcontracts.

Last year, GAO found numerous

problems with DCAA audit quality

at three locations in California,

including the failure to meet

professional auditing standards.

This report addresses audit quality

issues at DCAA offices nationwide.

GAO was asked to (1) conduct a

broad assessment of DCAA’s

management environment and

audit quality assurance structure,

(2) evaluate DCAA actions to date

to correct previously identified

problems, and (3) identify potential

legislative and other actions for

improving DCAA effectiveness and

independence. To achieve these

objectives, GAO analyzed DCAA’s

mission, strategic plan, audit

policies, and quality assurance

program; conducted interviews;

reviewed selected audits at DCAA

offices; and analyzed legislative

and other actions.

What GAO Recommends

GAO makes 17 recommendations

to DOD and the DOD Inspector

General (IG) to improve DCAA’s

management environment, audit

quality, and oversight. GAO also

discusses matters that Congress

should consider to enhance the

effectiveness and independence of

DCAA contract audits. DOD and

DOD IG generally agreed with

GAO’s recommendations,

concurring with all but two.

GAO found audit quality problems at DCAA offices nationwide, including

compromise of auditor independence, insufficient audit testing, and

inadequate planning and supervision. GAO’s conclusions stem from a review

of 69 audit assignments supporting contract award and administrative

decisions; an assessment of DCAA’s audit quality assurance structure, which

found similar audit quality problems but gave satisfactory ratings to deficient

audits; and DCAA’s rescission of 80 problem audit reports. The rescinded

audits supported decisions on pricing and contract awards and impacted the

planning and reliability of hundreds of other DCAA audits, representing

billions of dollars in DOD expenditures. GAO findings include the following.

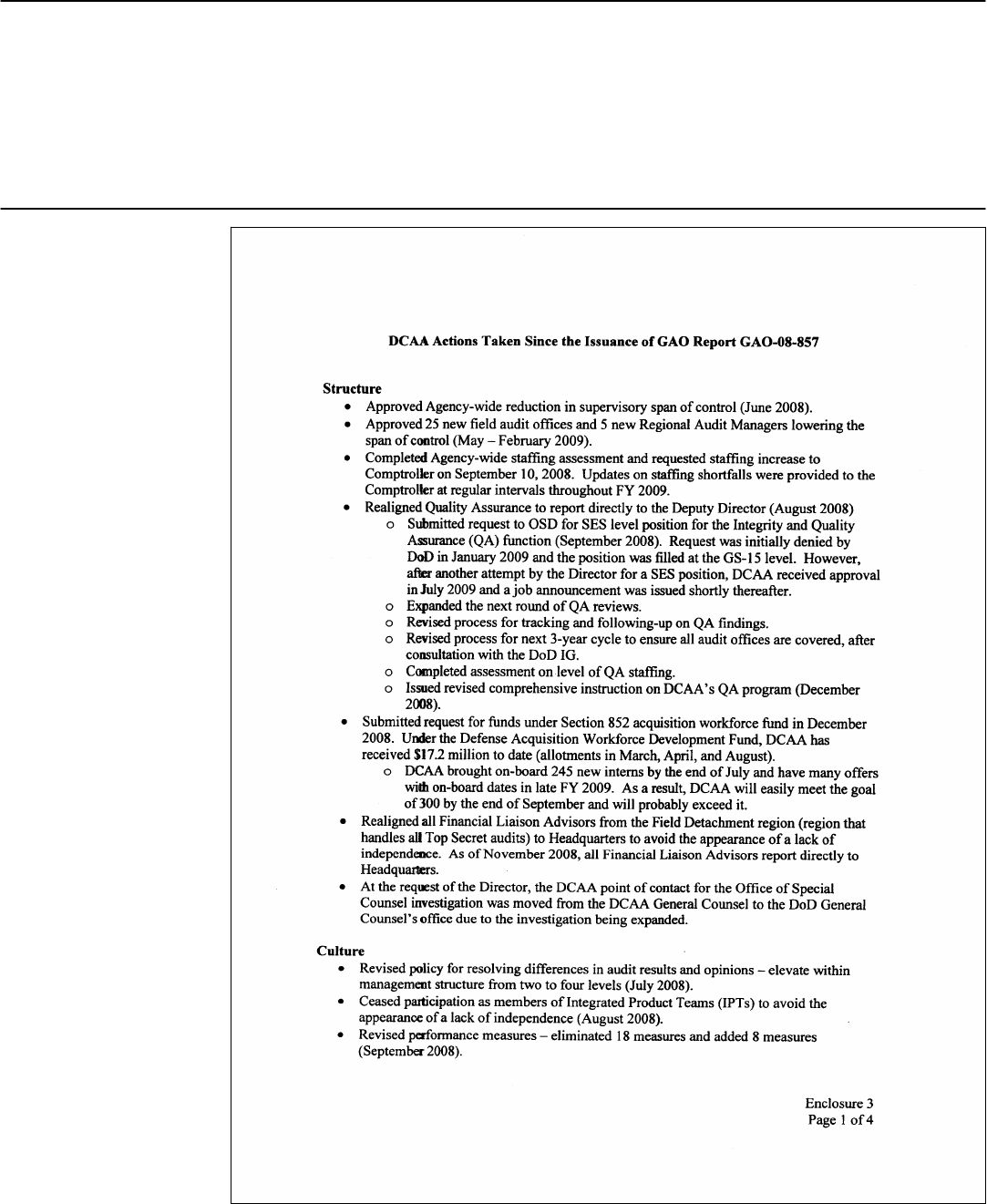

Selected Details of Audits GAO Reviewed

Contractor Audit Significant case study issues

Research and

development

grantee

Billing

system

• DCAA auditors spent 530 hours to support an audit of a

nonexistent billing system and reported adequate system controls.

• Instead, DCAA should have relied on the Single Audit Act report on

the grantee’s cash management system. DCAA agrees.

Combat

systems

Billing

system

• This was a new system and therefore high risk, but auditors

deleted key audit steps related to contractor policies and internal

controls over progress payments without explanation.

• One auditor told GAO he did not perform detailed tests because

“the contractor would not appreciate it.”

• DCAA allowed the contractor 7 months to address 6 significant

deficiencies, dropping 2 and downgrading the other 4.

• DCAA rescinded this audit report following GAO’s review.

Iraq

reconstruction

Accounting

system

• Contractor objected to draft report, which included 8 significant

deficiencies in the accounting system.

• Auditors dropped 5 significant deficiencies and downgraded 3

others to suggestions to improve without performing new work.

• Supervisory auditors directed audit staff to delete some audit

documents, generate others, and in one case, copy the signature

of a prior supervisor onto new documents making it appear that the

prior supervisor had approved a revised risk assessment.

• Supervisory auditor who approved altered documents was later

promoted to western region quality assurance manager, where he

served as quality control check over thousands of audits.

Source: GAO.

GAO found DCAA’s management environment and quality assurance structure

were based on a production-oriented mission that put DCAA in the role of

facilitating DOD contracting without also protecting the public interest. DCAA

has taken several positive steps. However, DOD and DCAA have not yet

addressed fundamental weaknesses in DCAA’s mission, strategic plan,

metrics, audit approach, and human capital practices that had a detrimental

effect on audit quality.

To improve DCAA oversight, the DOD Comptroller requested Defense

Business Board and “tiger team” reviews and established a DCAA Oversight

Committee. In addition, in the short-term, Congress could provide DCAA with

certain legislative protections and authorities similar to those available to IGs.

In the longer term, Congress may wish to consider organizational changes to

elevate DCAA to a component agency reporting to the Deputy Secretary or to

establish an independent governmentwide contract audit agency.

View GAO-09-468 or key components.

For more information, contact Gregory Kutz at

(202) 512-6722 or kutzg@gao.gov.

Page i GAO-09-468

Contents

Letter 1

Background 5

Nationwide Audit Quality Problems Are Rooted in DCAA’s Poor

Management Environment 14

DCAA Has Made Progress, but Correcting Fundamental Problems

in Agency Culture That Have Impacted Audit Quality Will

Require Sustained Leadership 42

Legislative and Other Actions To Improve DCAA’s Effectiveness

and Independence 61

Conclusions 69

Recommendations for Executive Action 70

Matters for Congressional Consideration 72

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 73

Appendix I Internal Control System Audits Did Not Meet

Professional Standards 83

Appendix II DCAA Does Not Perform Sufficient Work to Identify

and Collect Contractor Overpayments 100

Appendix III Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 105

Appendix IV Comments from the Department of Defense 113

Appendix V Comments from the Department of Defense Inspector

General 143

Tables

Table 1: Examples of DCAA Audit and Nonaudit Services 10

Table 2: Summary of Five Selected Internal Control Audits 20

Table 3: Summary of Five Selected Cost-Related Assignments 28

Table 4: Summary of Selected DCAA Audit Quality Review Results 34

DCAA Audit Environment

Table 5: GAGAS Noncompliance on 37 Selected Audits of

Contractor Controls 84

Table 6: Case Studies of Problem DCAA Cost-Related Assignments 103

Table 7: Summary of DCAA Audits Reviewed for GAGAS

Compliance 107

Table 8: Summary of DCAA Cost-Related Audits Reviewed 108

Figures

Figure 1: DCAA Opinions on Contractor Internal Control Systems

Audits 18

Figure 2: Comparison of DOD Contract Obligations and DCAA

Workforce for Fiscal Years 2002 through 2008 53

Figure 3: DCAA Questioned Costs and Amounts Sustained by

Contracting Officers 102

Abbreviations

AICPA American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

AT AICPA Statements on Attestation Standards

AT&L Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics

APO Audit Policy and Oversight (a Defense Inspector General

organization)

AU AICPA Statements on Auditing Standards

CAS Cost Accounting Standards

CAM Contract Audit Manual, also referred to as the DCAA Contract

Audit Manual, or DCAM

CFO Chief Financial Officer

COSO Committee on Sponsoring Organizations

DBB Defense Business Board

DCAA Defense Contract Audit Agency

DCAM DCAA Contract Audit Manual

DCMA Defense Contract Management Agency

DFARS Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement

DFAS Defense Finance and Accounting Service

DFMR Defense Financial Management Regulation

DOD Department of Defense

DPAP Director of Defense Procurement Policy

FAO field audit office

FAR Federal Acquisition Regulation

Page ii GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

FLA Financial Liaison Advisor

FMR Financial Management Regulation, also referred to as the

Defense Financial Management Regulation, or DFMR

GAGAS generally accepted government auditing standards

GAS Government Auditing Standards

GPRA Government Performance and Results Act

GS General Schedule

IG Inspector General

IGDH Inspector General, Defense Handbook

OIG Office of Inspector General

PCIE President’s Council on Integrity and Efficiency, renamed the

Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency

SAS AICPA Statements on Auditing Standards

SES Senior Executive Service

SIGIR Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction

SSAE AICPA Statements on Standards for Attestation Engagements

USC United States Code

USD Under Secretary of Defense

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page iii GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

Page 1 GAO-09-468

United States Government Accountability Office

Washington, DC 20548

September 23, 2009

The Honorable Joseph I. Lieberman

Chairman

The Honorable Susan M. Collins

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and

Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Claire C. McCaskill

Chairman

Subcommittee on Contracting Oversight

Committee on Homeland Security and

Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

This report addresses audit quality problems and independence issues at

the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA). In a September 2008 hearing

before the Committee, we testified

1

that DCAA failed to meet professional

audit standards at three locations in California. Specifically, we found that

the audit documentation for 14 selected audits at two locations did not

support reported opinions, that DCAA supervisors dropped findings and

changed audit opinions without adequate audit evidence for their changes,

and that sufficient audit work was not performed to support audit

opinions and conclusions. Further, we found that contractor officials and

the Department of Defense (DOD) contracting community improperly

influenced the audit scope, conclusions, and opinions of several audits,

including forward pricing audits at a third location—a serious

independence issue. During our investigation, DCAA managers took

actions against their staff at two locations that served to intimidate

auditors and create an abusive work environment. For example, we

learned of verbal admonishments, reassignments, and threats of

disciplinary action against auditors who spoke with or contacted our

investigators, DOD investigators, or DOD contracting officials.

1

GAO, DCAA Audits: Allegations That Certain Audits at Three Locations Did Not Meet

Professional Standards Were Substantiated, GAO-08-993T (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10,

2008).

DCAA Audit Environment

At the time of the September 2008 hearing, we were conducting a broad

assessment of DCAA’s management environment and audit quality

assurance structure at DCAA offices nationwide. Given the evidence

presented at this hearing, you requested that we expand our ongoing

assessment. This report therefore presents (1) an assessment of DCAA’s

management environment and quality assurance structure; (2) an analysis

of DCAA’s corrective actions in response to our July 2008 report,

2

the

Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller/Chief Financial Officer)

3

“tiger

team” review,

4

and the Defense Business Board study;

5

and (3) potential

legislative and other actions that could improve DCAA’s effectiveness and

independence.

To assess DCAA’s overall management environment and quality assurance

structure, we analyzed DCAA’s mission statement and strategic plan,

performance metrics, policies and audit guidance, and system of quality

control. We also reviewed audit documentation for selected audits at

certain field audit offices (FAO) in each of DCAA’s five regions for

compliance with generally accepted government auditing standards

(GAGAS)

6

and other applicable standards. We selected 37 audits of

contractor internal control systems performed by seven geographically

disperse DCAA field offices within the five DCAA regions during fiscal

years 2004 through 2006.

7

These were the most recently completed fiscal

years at the time we initiated our audit. Our approach focused on DCAA

offices that reported predominately adequate, or “clean,” opinions on

audits of contractor internal controls over cost accounting, billing, and

2

GAO, DCAA Audits: Allegations That Certain Audits at Three Locations Did Not Meet

Professional Standards Were Substantiated, GAO-08-857 (Washington, D.C.: July 22, 2008).

3

Hereafter referred to as the DOD Comptroller/CFO.

4

Under Secretary of Defense—Comptroller, Memorandum for Director Defense Contract

Audit Agency, Subject: Implementation of Corrective Actions, (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 20,

2008).

5

Defense Business Board, Report to the Secretary of Defense: Independent Review Panel

Report on the Defense Contract Audit Agency, October 2008.

6

GAO, Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards, GAO-03-673G (Washington,

D.C.: June 2003) and GAO-07-731G (Washington, D.C.: July 2007).

7

In the case of follow-up audits, we also reviewed the documentation for the previous audit

to gain an understanding of the scope of work and deficiencies identified in the prior audit.

Page 2 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

cost estimating systems issued in fiscal years 2005 and 2006.

8

We selected

DCAA offices that report predominately adequate opinions on contractor

systems and related internal controls because contracting officers rely on

these opinions for three or more years to make decisions on pricing and

contract awards, and payment. For example, audits of estimating system

controls support negotiation of fair and reasonable prices.

9

Also, the FAR

requires contractors to have an adequate accounting system prior to award

of a cost-reimbursable or other flexibly priced contract.

10

Billing system

internal control audit results support decisions to authorize contractors to

submit invoices directly to DOD and other federal agency disbursing

offices for payment without government review.

11

In addition, DCAA uses

the results of internal control audits to assess risk and plan the nature,

extent, and timing of tests for other contractor audits and other

assignments. When a contractor has received an adequate opinion on its

systems and related controls, DCAA would assess the risk for subsequent

internal control and cost-related audits as low and would perform less

testing on these audits. Although our selection of the seven offices and 37

internal control audits was not statistical, it represented about 9 percent of

the total 76 DCAA offices that issued audit reports on contractor internal

controls and nearly 18 percent of the 40 offices that issued 8 or more

reports on contractor internal controls during fiscal year 2006. Of the 37

internal control audits we reviewed, 32 reports were issued with adequate

opinions and 5 reports were issued with inadequate-in-part opinions.

At the same seven DCAA field offices, we selected an additional 32 paid

voucher, overpayment, request for equitable adjustment, and incurred cost

assignments that were completed during fiscal years 2004 through 2006 for

review of supporting documentation to determine whether DCAA auditors

were identifying and reporting contractor overpayments and billing

8

In selecting the seven DCAA offices, we considered a 2-year history of internal control

audit results. The seven DCAA offices we selected reported adequate opinions on 89

percent or more of the internal control reports they issued during fiscal year 2006. During

fiscal year 2005, 4 of the 7 offices reported adequate opinions in 85 percent or more of the

internal control reports they issued, and the other 3 offices issued adequate opinions in 50

to 69 percent of the internal control audit reports they issued.

9

DCAA, Contract Audit Manual (CAM) 5-1202.1a and Defense Federal Acquisition

Regulation Supplement (DFARS) 215.407-5.

10

FAR §§ 16.104(h) and 16.301-3(a)(1).

11

FAR § 42.101 and DFARS § 242.803.

Page 3 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

errors.

12

In total, we reviewed 69 DCAA audits and cost-related

assignments.

13

To address our second objective, we assessed the status

and analyzed several key actions that DCAA initiated as a result of our

earlier investigation, including changes in performance metrics and policy

and procedural guidance, as well as DCAA efforts in response to DOD

Comptroller/CFO and Defense Business Board

14

recommendations. To

achieve our third objective to identify potential legislative and other

actions that could improve DCAA’s effectiveness and independence, we

considered DCAA’s current role and responsibilities; the framework of

statutory authority for auditor independence in the Inspector General Act

of 1978, as amended;

15

best practices of leading organizations that have

made cultural and organizational transformations; our past work on DCAA

organizational alternatives; GAGAS criteria for auditor integrity,

objectivity, and independence; and GAO’s Standards for Internal Control

In the Federal Government

16

on managerial leadership and oversight.

Throughout our audit, we met with the DCAA Director and DCAA

headquarters policy, quality assurance, and operations officials and DCAA

region and FAO managers, supervisors, and auditors. We also met with

DOD Office of Inspector General (OIG) auditors responsible for DCAA

audit oversight and DOD OIG hotline office staff. We conducted this

performance audit from August 2006 through December 2007, at which

time we suspended this work to complete our investigation of hotline

complaints regarding audits performed at three DCAA field offices. We

resumed our work on this audit in October 2008 and performed additional

12

Contractor overpayments can occur as a result of errors made by paying offices, such as

duplicate payments and payments in excess of amounts billed, and contractor billing

errors, such as using the wrong overhead rate, failing to withhold designated amounts on

progress payments, duplicate billings, or billing for unallowable cost. Recoveries of

overpayments can be accomplished through refunds, subsequent billing offsets, or other

adjustments to correct billing errors.

13

Although we selected 73 assignments for review, two internal control assignments were

assist audits and two cost related assignments were not completed assignments. As a

result, we did not consider these four assignments in our analysis, and we discuss the

results of our analysis of the 69 completed assignments that we reviewed.

14

On August 19, 2008, at the request of the DOD Defense, Comptroller, the Deputy

Secretary of Defense established an independent review panel under the Defense Business

Board (DBB) to review DCAA operations and make recommendations for improvements.

15

Codified in an appendix to Title 5 of the United States Code (hereafter 5 U.S.C. App.).

16

GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO/AIMD-00-21.3.1

(Washington, D.C.: November 1999).

Page 4 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

work through mid-September 2009 to evaluate DCAA’s quality assurance

program during fiscal years 2007 and 2008, assess DCAA corrective actions

on identified audit quality weaknesses, and consider legislative and

organizational placement options. During our assessment of DCAA

corrective actions and analysis of legislative and organizational placement

options for DCAA, we met with the former DOD Comptroller/CFO to

discuss plans for Office of Comptroller/CFO and Defense Business Board

reviews, and we continued to meet with and obtain information from the

new DOD Comptroller/CFO and his staff. We also met with Comptroller’s

new DCAA Oversight Committee, which includes the Auditors General of

the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force; the DOD Director of Defense

Procurement and Acquisition Policy; and the DOD Deputy General

Counsel for Acquisition. We obtained DOD and DOD OIG comments on a

draft of this report. DOD and DOD IG comments are summarized in the

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation section of this report. DOD

comments are reprinted in appendix IV and DOD OIG comments are

reprinted in appendix V. We conducted our audit in accordance with

generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards

require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate

evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions

based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained

provides a reasonable basis for findings and conclusions based on our

audit objectives. We performed our investigative procedures in

accordance with quality standards set forth by the Council of the

Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency (formerly the President’s

Council on Integrity and Efficiency). A detailed discussion of our

objectives, scope, and methodology is included in appendix III.

DOD contract management continues to be a high-risk area for the

government.

17

With hundreds of billions of taxpayer dollars at stake,

strong controls are needed to provide reasonable assurance that contract

funds are not lost to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement. Downsizi

of contract administration personnel during the 1990s coupled wit

increased contract spending since 2000 have exacerbated the risks

associated with DOD contract management. Our work continues to

Background

ng

h

17

GAO, High-Risk Series: An Update, GAO-09-271 (Washington, D.C.: January 2009).

Page 5 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

identify significant problems with federal agency contract payments

18

and

contract management.

19

DCAA is charged with a critical role in DOD contractor oversight by

providing auditing, accounting, and financial advisory services in

connection with the negotiation, administration, and settlement of

contracts and subcontracts. DCAA also performs contract audit services

and payment reviews for other federal agencies, as requested, on a fee-for-

service basis. DCAA contract audit services are intended to be a key

control to help assure that prices paid by the government for needed

goods and services are fair and reasonable and that contractors are

charging the government in accordance with applicable laws, regulations

(e.g., Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) and Defense Federal

Acquisition Supplement (DFARS), standards (e.g., Cost Accounting

Standards (CAS)), and contract terms.

DCAA is headed by a director who reports to the Under Secretary of

Defense (Comptroller/CFO). DCAA’s placement provides the DOD

Comptroller/CFO with access to financial information on defense

contracts and allows the Comptroller/CFO to make this information

available to the Secretary and Deputy Secretary of Defense. In addition, it

permits the Comptroller/CFO to elevate policy issues concerning the

scope of DCAA’s authority and level of resources. The DCAA Director is

18

GAO, Global War on Terrorism: DOD Needs to More Accurately Capture and Report the

Costs of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom, GAO-09-302

(Washington, D.C.: Mar. 17, 2009); Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Internal

Control Deficiencies Resulted in Millions of Dollars of Questionable Contract Payments,

GAO-08-54 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 15, 2007); Defense Contract Management: DOD’s Lack

of Adherence to Key Contracting Principles on Iraq Oil Contract Put Government

Interests at Risk, GAO-07-839 (Washington, D.C.: July 31, 2007); Hanford Waste Treatment

Plant: Department of Energy Needs to Strengthen Controls over Contractor Payments

and Project Assets, GAO-07-888 (Washington, D.C.: July 20,2007); Iraq Contract Costs:

DOD Consideration of Defense Contract Audit Agency’s Findings, GAO 06-1132

(Washington, D.C. Sept. 25, 2006); Department of Energy, Office of Worker Advocacy:

Deficient Controls Led to Millions of Dollars in Improper and Questionable Payments to

Contractors, GAO-06-547 (Washington, D.C.: May 31, 2006); and Federal Bureau of

Investigation: Weak Controls over Trilogy Project Led to Payment of Questionable

Contractor Costs and Missing Assets, GAO-06-306 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 28, 2006).

19

GAO, Defense Acquisitions: Assessments of Selected Weapon Programs, GAO-09-326SP

(Washington, D.C.: Mar. 30, 2009); Defense Management: Actions Needed to Overcome

Long-standing Challenges with Weapon Systems Acquisition and Service Contract

Management, GAO-09-362T (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 11, 2009); and Defense Acquisitions:

DOD’s Increased Reliance on Service Contractors Exacerbates Long-standing Challenges,

GAO-08-621T (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 23, 2008).

Page 6 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

responsible for day-to-day management of DCAA, development of strategic

plans, audit guidance and procedures, and the quality of DCAA’s audit

services. DCAA’s Contract Audit Manual (CAM)

20

prescribes the

standards, policies, and techniques to be followed by DCAA personnel in

conducting contract audits. DCAA emphasizes and supplements CAM

guidance through policy memorandums and other written notices, as well

as through training and oral communications.

The IG Act gives the DOD IG broad responsibilities to provide policy

direction for and to conduct, supervise, and coordinate audits and

investigations in DOD and in contractor operations, if warranted. DOD IG

duties pertaining to DCAA include (1) providing policy direction for all

DOD audits; (2) investigating fraud, waste, and abuse uncovered as a

result of audits; (3) monitoring and evaluating adherence by all DOD

auditors to audit policies, procedures, and standards; and (4) requesting

assistance as needed from other auditors in DOD. As part of its audit

policy and oversight responsibilities, the DOD IG reviews DCAA’s system

of audit quality control on a 3-year basis that is intended to meet the

requirements under GAGAS for a peer review.

DCAA History and

Organizational Structure

Audits of military contracts can be traced back to at least the World War I

era. Initially, the various branches of the military had their own contract

audit function and associated instructions and accounting rulings.

Contractors and government personnel recognized the need for

consistency in both contract administration and audit. The Navy and the

Army Air Corps made the first attempt to perform joint audits in 1939. By

December 1942, the Navy, the Army Air Corps, and the Ordnance

Department had established audit coordination committees for selected

areas where plants were producing different items under contracts for

more than one service. On June 18, 1952, the three military services jointly

issued a contract audit manual that later became the DCAA CAM.

In May 1962, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara instituted “Project

60” to examine the feasibility of centrally managing the field activities

20

DCAA, Contract Audit Manual (CAM), DCAAM 7640.1.

Page 7 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

concerned with contract administration and audit.

21

An outcome of this

study was the decision to establish a single contract audit capability within

DOD and DCAA was established on June 8, 1965.

22

At that time, DCAA’s

mission to perform all necessary contract audits for DOD and provide

accounting and financial advisory services regarding contracts and

subcontracts to all DOD components responsible for procurement and

contract administration was established. The former Deputy Comptroller

of the Air Force was selected as the DCAA Director and the former

Director of Contract Audit for the Navy, was selected as the Deputy

Director. DCAA was placed under management control of the Under

Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), where it remains today.

DCAA consists of a headquarters office at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, and six

major organizational components—a field detachment office, which

handles audits of classified contracting activity, and five regional offices

within the United States. The regional offices manage field audit offices

(FAO), which are identified as branch offices, resident offices, or

suboffices. Resident offices are located at larger contractor facilities in

order to facilitate DCAA audit work. In addition, regional office directors

can establish suboffices as extensions of FAOs to provide contract audit

services more economically. A suboffice depends on its parent FAO for

release of audit reports and other administrative support. In total, there

are more than 300 FAOs and suboffices throughout the United States and

overseas. During fiscal year 2008, DCAA employed about 3,600 auditors at

more than 300 FAOs throughout the United States, Europe, the Middle

East, and in the Pacific to perform audits and provide nonaudit services in

support of contract negotiations related to approximately 10,000

contractors.

DCAA Audit and Nonaudit

Services

DCAA’s mission encompasses both audit and nonaudit services in support

of DOD contracting and contract payment functions. FAR subpart 42.1,

“Contract Audit Services,” and DOD Directive 5105.36, Defense Contract

21

Project 60 also resulted in consolidation of the military services’ contract management

activities under the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA), formerly the Defense

Contract Management Command (DCMC) within the Defense Logistics Agency. On March

27, 2000, DCMC was established as DCMA under the authority of the Under Secretary of

Defense (Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics).

22

DOD, General Plan: Consolidation of Department of Defense Contract Audit Activities

into the Defense Contract Audit Agency (Feb. 17, 1965).

Page 8 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

Audit Agency (DCAA), establish DCAA as the department’s contract audit

agency

23

and set forth DCAA’s responsibilities.

FAR 42.101 prescribes contract audit responsibilities as submitting

information and advice to the requesting activity, based on the analysis of

contractor financial and accounting records or other related data as to the

acceptability of the contractors’ incurred and estimated costs; reviewing

the financial and accounting aspects of contractor cost control systems;

and, performing other analyses and reviews that require access to

contractor financial and accounting records supporting proposed and

incurred costs. DOD Directive 5150.36 lists several responsibilities and

functions that shall be performed by the DCAA Director,

24

including:

• “Assist in achieving the objective of prudent contracting by providing

DOD officials responsible for procurement and contract

administration

25

with financial information and advice on proposed or

existing contracts and contractors, as appropriate.”

• “Audit, examine, and/or review contractors’ and subcontractors’

accounts, records, documents, and other evidence; systems of internal

control; [and] accounting, costing, and general business practices and

procedures; to the extent and in whatever manner is considered

necessary to permit proper performance of other functions ….” These

other functions cover contract audit and nonaudit services. In addition,

the Directive states that the DCAA Director shall perform such other

functions as may be assigned by the Secretary and Deputy Secretary of

Defense or the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller/CFO).

• “Approve, suspend, or disapprove costs on reimbursement vouchers

received directly from contractors, under cost-type contracts,

transmitting the vouchers to the cognizant Disbursing Officer.”

DCAA uses the term audit to refer to a variety of evaluations of various

types of data.

26

In fiscal year 2008, DCAA reported that over 97 percent of

its service work hours were spent on audits, meaning that DCAA has opted

to provide nearly all of its services to the contracting and finance

23

DODD 5105.36, paragraph 4.2, reissued on February 28, 2002.

24

DODD 5105.36, paragraphs 5.1 through 5.14.

25

Contract administration responsibilities are set forth in FAR Subparts 42.2 and 42.3.

26

CAM 2-001.

Page 9 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

communities under applicable auditing standards, as discussed below.

Table 1 lists several audit and nonaudit services provided by DCAA during

the three phases of the contracting process—pre-award, contract

administration, and close-out—and cites the statutory and regulatory

provisions that authorize or establish the need to have DCAA perform the

service. DCAA audits also support the contract payment process both

directly and indirectly. For example, audits of contractor incurred cost

claims and voucher reviews directly support the contract payment process

by providing the information necessary to certify payment of claimed

costs.

27

Other audits of contractor systems, including audits of contractor

internal controls, CAS compliance, and defective pricing, indirectly

support the payment process by providing assurance about contractor

controls over cost accounting, cost estimating, purchases, and billings that

the agency may rely upon when making contract decisions, such as

determinations of reasonable and fair prices on negotiated contracts. For

example, an accounting system deemed to be adequate by a DCAA audit

permits progress payments based on costs to be made without further

audit.

28

Table 1: Examples of DCAA Audit and Nonaudit Services

Payment support

Contract phase and

assignment Audit and Nonaudit services

Contracting

support Direct Indirect

Pre-award phase:

Accounting system

a

Audit: DCAA determines adequacy of the contractor’s accounting

system prior to award of a cost-reimbursable or other flexibly

priced contract. FAR § 16.301-3(a)(1).

X X

Contractor accounting

disclosure statements

Audit: DCAA reviews the contractor’s Disclosure Statement for

adequacy and CAS compliance and determines whether the

contractor’s Disclosure Statement is current, accurate, and

complete. DCAA also reviews Disclosure Statements during the

post award phase if contractors revise them. FAR §§ 30.202-6(c),

30.202-7 and 30.601(c).

X X

Estimating system

a

Audit: DCAA determines adequacy of contractor estimating

systems. FAR § 15.407-5 and DFARS § 252.215-7002(d), (e).

X X

27

Disbursing officers are authorized to make payments on the authority of a voucher

certified by an authorized certifying officer, who is responsible for the legality, accuracy,

and propriety of the payment. 31 U.S.C. §§ 3325, 3521(a), and 3528(a).

28

FAR § 32.503-4.

Page 10 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

Payment support

Contract phase and

assignment Audit and Nonaudit services

Contracting

support Direct Indirect

Contract price

proposals and forward

pricing proposals

b

Audit: DCAA examines contractor records to ensure that cost or

pricing data is accurate, current, and complete and supports the

determination of fair and reasonable prices. 10 U.S.C. §§ 2306a

and 2313 (DOD) and 41 U.S.C. § 254d (other agencies); FAR

Subpart 15.4 (esp. FAR § 15.404-2(c)) and § 52.215-2(c); and

DFARS § 215.404-1.

X X

Financial liaison

advisory services

b

Nonaudit: DCAA Director establishes and maintains liaison

auditors and financial advisors, as appropriate, at major procuring

and contract administration offices. These services are also

provided during the post-award phase, as needed. DODD

5105.36, paras. 7.1.1 and 5.9.

X

X

Post award/administration phase:

Internal control system

audits (generally)

Audit: DCAA reviews the financial and accounting aspects of the

contractor’s cost control systems, including the contractor’s

internal control systems. FAR § 42.101(a)(3) and DFARS §

242.7501.

X X

Billing system audits

a

Audit: DCAA determines adequacy of contractors’ billing system

controls and reviews accuracy of paid vouchers. DCAA uses audit

results to support approval of contractors to participate in the

direct-bill program. FAR § 42.101 and DFARS § 42.803 (b)(i)(C).

X X

Purchasing system

review b

Audit: DCAA determines adequacy of a contractor’s or

subcontractor’s purchasing system. FAR Subpart 44.3.

X X

Progress payments

b

Audit: DCAA verifies amount claimed, determines allowability of

contractor requests for cost-based progress payments, and

determines if the payment will result in undue financial risk to the

government. FAR §§ 32.503-3, 32.503-4, and 52.232-16.

X X

Incurred cost claims

a

Audit: DCAA determines acceptability of the contractors’ claimed

costs incurred and submitted by contractors for reimbursement

under cost-reimbursable, fixed-price incentive, and other types of

flexibly priced contracts and compliance with contract terms, FAR,

and CAS, if applicable. FAR §§ 42.101, 42.803(b), and DFARS §

242.803.

X X

Billing rates and final

indirect cost rates

a

Audit: DCAA establishes billing rates for interim indirect costs and

final indirect cost rates. FAR §§ 42.704, 42.705 and 42.705-2 and

DFARS § 42.705-2.

X X

Defective pricing

b

Audit: DCAA determines the amount of cost adjustments related

to defective pricing. See above authorities to audit contractor cost

and pricing data and FAR § 15.407-1.

X X

CAS compliance

b

Audit: DCAA determines contractor and subcontractor compliance

with CAS set forth in 48 CFR § 9903.201 and determines cost

impacts of noncompliance. FAR §§ 1.602-2, 30.202-7, and

30.601(C).

X X

Other specially

requested services

Audit and nonaudit services: DCAA conducts performance audits

and other audits based on requests from DOD components and

requests from other federal agencies. DOD Directive 5105.36,

Sec. 5.

X X

Page 11 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

Payment support

Contract phase and

assignment Audit and Nonaudit services

Contracting

support Direct Indirect

Paid voucher reviews

a

Nonaudit services: DCAA reviews vouchers after payment to

support continued contractor participation in the direct bill

program. CAM 6-1007.6; FAR § 42.803; DFARS § 242.803;

DODD 5105.36, paras. 5.4 and 5.5; and DOD Financial

Management Regulation (FMR), vol. 10, ch. 10, para. 100202.

X X

Approval of vouchers

prior to payment

a

Nonaudit: DCAA reviews and approves contractor interim

vouchers for payment and suspends payment of questionable

costs. FAR § 42.803; DFARS § 242.803(b)(i)(B); DOD Directive

5105.36, paras. 5.4 and 5.5; and DOD FMR vol. 10, ch. 10, para.

100202.

X X

Overpayment reviews

a

Non audit services: At the request of the contracting officer, DCAA

reviews contractor data to identify potential contract

overpayments. FAR §§ 2.605, 52.216-7(g), (h)2.

X X

Close-out/termination phase:

Contract close-out

procedures and

audits

a

Audit: DCAA reviews final completion vouchers and the

cumulative allowable cost worksheet and may review contract

closing statements. DFARS § 242.803(b)(i)(D).

X X

Source: GAO analysis.

a

Indicates DCAA audit and nonaudit services covered in this audit.

b

Indicates types of audits covered in our prior investigation (GAO-08-857). We reviewed progress

payment and contract close-out audits that related to audits in our earlier investigation or this audit

where the auditors considered the evidence in those audits.

Importance of Audits in

Accordance with GAGAS

DCAA policy states

29

that it follows GAGAS

30

when conducting audits.

These standards provide a framework for conducting high quality

government audits and attestation engagements. These standards also

provide guidelines to help government auditors maintain competence,

integrity, objectivity, and independence in their work and require that they

obtain sufficient evidence to support audit conclusions and opinions.

When auditors are required to follow GAGAS or are representing to others

that they followed GAGAS, they should follow all applicable GAGAS

requirements and should refer to compliance with GAGAS in the auditor’s

report.

31

Most DCAA audits are performed as attestation audits under

GAGAS. For attestation audits, GAGAS incorporates the American

29

CAM, 2-101. Except where stated otherwise in this report, various types of evaluations

entailing different levels of assurance that DCAA refers to as audits—such as examinations,

attestations, and reviews—were subject to GAGAS.

30

GAO-03-673G, §1.01, and GAO-07-731G, §1.03.

31

GAO-07-731G, § 1.11.

Page 12 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) general standard on

criteria, and the field work and reporting standards and the related

Statements on Standards for Attestation Engagements (SSAE), unless

specifically excluded or modified by GAGAS.

32

DCAA also conducts

performance audits upon request. This report addresses DCAA attestation

audits and related supporting assignments.

GAGAS state that the public expects auditors to observe the principles of

serving the public interest and maintaining the highest degree of integrity,

objectivity, and independence in discharging their professional

responsibilities. Serving the public interest and honoring the public trust

are critical when performing government audits. Auditors increase public

confidence when they conduct their work with an attitude that is

objective, fact-based, nonpartisan, and non-ideological with regard to

audited entities and users of the auditors’ reports. Auditors also should be

intellectually honest and free of conflicts of interest in discharging their

professional responsibilities.

33

Management of the audit organization sets

the tone for ethical behavior throughout the organization by maintaining

an ethical culture, clearly communicating acceptable behavior and

expectations to each employee and creating an environment that

reinforces and encourages ethical behavior throughout all levels of the

organization.

34

The credibility of auditing in the government sector is

based on auditors’ objectivity and integrity in discharging their

professional responsibilities.

35

32

GAO-03-673G, § 6.01, and GAO-07-731G, § 6.01.

33

GAO-07-731G, §§ 2.06 through 2.10.

34

GAO-07-731G, § 2.01.

35

GAO-07-731G, § 2.10.

Page 13 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

We found audit quality problems at DCAA offices nationwide, as

demonstrated by serious quality problems in the 69 audits and cost-related

assignments we reviewed, DCAA’s ineffective audit quality assurance

program, and DCAA’s rescission of 80 audit reports in response to our

work.

36

Of the 69 audits and cost-related assignments we reviewed for this

report, 65 exhibited serious GAGAS or other deficiencies similar to those

found in our prior investigation, including compromise of auditor

independence, insufficient audit testing, and inadequate planning and

supervision. Although not as serious, the remaining four audits also had

GAGAS compliance problems. The 69 audits and cost-related assignments

we reviewed included 43 audits that DCAA reported were performed in

accordance with GAGAS and 26 non-GAGAS cost-related assignments,

including 10 overpayment and 16 paid voucher assignments. According to

DCAA officials, DCAA rescinded the 80 audit reports because the audit

evidence was outdated, insufficient, or inconsistent with reported

conclusions and opinions and reliance on the reports for contracting

decisions could pose a problem. Nearly one third (24) of the 80 rescinded

reports relate to unsupported opinions on contractor internal controls,

which were used as the basis for risk-assessments and planning on

subsequent internal control and cost-related audits. Other rescinded

reports relate to CAS compliance and contract pricing decisions. Because

the conclusions and opinions in the rescinded reports were used to assess

risk in planning subsequent audits, they impact the reliability of hundreds

of other audits and contracting decisions covering billions of dollars in

DOD expenditures. We found that DCAA’s focus on a production-oriented

mission led DCAA management to establish policies, procedures, and

training that emphasized performing a large quantity of audits to support

contracting decisions over audit quality. An ineffective quality assurance

structure compounded this problem.

Nationwide Audit

Quality Problems Are

Rooted in DCAA’s

Poor Management

Environment

Audit Quality Problems

Found in All Audits GAO

Reviewed

We found audit quality problems, including GAGAS compliance problems,

with all 37 audits of contractor internal controls and the 4 incurred cost

and the 2 request for equitable adjustment audits we reviewed at 7 FAOs

across the 5 DCAA regions covered in this audit. In addition, none of the

26 cost-related assignments we reviewed from these same FAOs included

sufficient testing to identify contractor overpayments and billing errors.

36

According to documentation provided by DCAA as of the end of July 2009, the 80

rescinded reports include 62 reports related to findings in our July 2008 investigative report

and 18 reports related to this audit.

Page 14 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

For additional details on our analysis of these DCAA audits and

assignments, including narrative case-studies, see appendixes I and II.

DCAA performs attestation audits of contractors’ systems for cost

accounting, estimating, and billing to gather evidence to express an

opinion on the adequacy of the contractor’s systems and related internal

controls for compliance with applicable laws and regulations and contract

terms. A contractor must have an adequate accounting system to be

awarded a government cost-reimbursement contract, an adequate billing

system to submit invoices for payment without government review, and an

acceptable estimating system to support a contracting officer’s approval of

pricing proposals. A secondary objective of DCAA’s audits of contractor

systems and controls is to determine the degree of reliance that can be

placed on the contractor’s internal controls as a basis for planning the

scope of other related audits. For example, if a contractor receives an

adequate opinion on various systems control audits, auditors assess risk as

low and reduce the level of testing on subsequent internal control and

cost-related audits, including audits of contractors’ annual incurred cost

claims. Although the reports for all 37 audits of contractor internal

controls that we reviewed stated that the audits were performed in

accordance with GAGAS, we found GAGAS compliance issues with all of

these audits. Examples of GAGAS compliance issues we found included:

Internal Control Audits

Independence issues. For 7 audits we reviewed, DCAA independence

was compromised because auditors provided material nonaudit services

to a contractor they later audited; experienced access to records problems

that were not fully resolved; or significantly delayed report issuance in

order to allow the contractors to resolve cited deficiencies. GAGAS state

that auditors should be free from influences that restrict access to records

or improperly modify audit scope.

37

Insufficient evidence. We found that 33 of the 37 internal control audits

did not include sufficient testing of internal controls to support auditor

conclusions and opinions. GAGAS for examination-level attestation

engagements require that sufficient evidence be obtained to provide a

reasonable basis for the conclusion that is expressed in the report.

38

However, our review of audit documentation often found that only two,

three, or sometimes five transactions were tested to support audit

37

See GAO-03-673G, § 3.19, and GAO-07-731G, § 3.10.

38

GAO-03-673G, § 6.04b.

Page 15 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

conclusions, and the audit documentation did not contain a justification

for the small sample sizes selected for testing. For internal control audits,

which are relied on for 2 to 4 years and sometimes longer, the auditors

would be expected to test a representative selection of transactions across

the year and not transactions for just one day, one month, or a couple of

months.

39

For many controls, the procedures performed consisted of

documenting the auditors’ understanding of controls, and the auditors did

not test the effectiveness of the implementation and operation of controls.

Generally, the basis for an auditor’s determination of sufficient testing

should include (1) an adequate risk assessment, taking into consideration

any auditor alerts arising from related audits, past findings, and corrective

actions; (2) the contractor’s overall control environment; and (3) the

nature and volume of transactions and associated materiality and risk of

error. For example, decisions on sufficient testing of contractor internal

controls would include consideration of the number and types of contracts

or proposals; the nature, dollar amount, and volume of transactions; and

key control attributes or special characteristics of the transactions.

Further, a representative selection would include a representative number

of transactions from a population of transactions representing a

reasonable period of time, in order for test results to support conclusions

and opinions on the overall adequacy of the contractor’s systems and

effectiveness of the related controls. For example, under the GAO/PCIE

Financial Audit Manual,

40

the minimum sample size for an attribute

sample of a control would be 45 items.

Reporting problems. According to GAGAS, audit reports should, among

other matters, identify the subject matter being reported and the criteria

used to evaluate the subject matter. Criteria identify the required or

desired state or expectation with respect to the program or operation and

provide a context for evaluating evidence and understanding the findings.

41

None of the 37 internal control audit reports we reviewed cited specific

criteria used in individual audits. Instead, the reports uniformly used

boilerplate language to state that DCAA audited for compliance with the

“FAR, CAS, DFARS, and contract terms.” As a result the user of the report

39

AICPA Statements on Auditing Standards, AU 350, and Audit and Accounting Guide:

Audit Sampling, §§ 3.14, 3.29-3.34, 3.58, and 3.61.

40

GAO/PCIE, Financial Audit Manual, GAO-08-585G (Washington, D.C.: July 2008).

41

GAO-07-731G, § 4.15.

Page 16 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

does not know the specific Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), Cost

Accounting Standards (CAS), or contract terms used as criteria to test

contractor controls. This makes it difficult for users of the reports to

determine whether a particular report provides the level of assurance

needed to make contracting decisions.

The lack of sufficient support for the audit opinions on 33 of the 37

internal control audits we reviewed rendered them unreliable for decision

making on contract awards, direct billing privileges, the reliability of cost

estimates, and reported direct cost and indirect cost rates. For example,

the FAR requires

42

government contracting officers to determine the

adequacy of a contractor’s accounting system before awarding a cost-

reimbursement contract. Of the 9 audits of contractor accounting system

internal controls that we reviewed, only two of the audits included

sufficient testing to support DCAA’s audit opinion that internal controls

over the contractors’ accounting systems were adequate. In addition, none

of the 20 audits of contractor billing system internal controls we reviewed

contained sufficient testing of controls to support the reported opinions.

Adequate opinions on billing system audits are the basis for DCAA

decisions to approve contractors for the direct bill program, whereby

contractors submit invoices directly to a government disbursing office

without prior review.

43

Four of the 6 audits of contractor estimating

system controls that we reviewed did not include sufficient testing to

support the reported opinions. DOD requires

44

that large contractors have

acceptable estimating systems. Opinions on contractor estimating system

support DCAA decisions on the extent of testing performed on contract

proposals. Neither of the two internal control audits of contractor indirect

and other direct costs we reviewed included sufficient testing to support

reported opinions. As shown in figure 1, at the time these audits were

performed, DCAA policy guidance provided for three categories of

opinions on internal control audits. This policy provided for different

opinions and criteria for judging them based on the severity of the

problems identified. Professional standards have long recognized differe

levels of severity with regard to reporting deficiencies and material

weakness

s

nt

es in internal controls.

42

FAR §§ 16.104(h) and 16.301-3(a)(1).

43

FAR § 42.101 and DFARS § 242.803(b)(i)(C).

44

DFARS § 215.407-5-70; see FAR § 15.407-5.

Page 17 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

Figure 1: DCAA Opinions on Contractor Internal Control Systems Audits

Source: GAO analysis of DCAA policy.

Risk

Adequate

Inadequate

In

No significant

deficiencies were

identified in the audit

Auditors identified one

or more significant

deficiencies that render

the entire contractor

system unreliable

Auditors identified one

or more significant

deficiencies that affect

parts of the contractor’s

system

Scope of future audits will be decreased based on assurance provided by

adequate controls.

Contractor is required to make improvements and DCAA is to perform follow-up

testing within 6 months.

Inadequate opinion requires expanded audit scopes on other audits because

controls do not provide reasonable assurance that data generated by the

contractor’s system are reliable.

Contractor is required to make improvements, and DCAA is to perform follow-up

testing within 6 months.

Inadequate in part opinion also requires expanded audit scopes on future and

concurrent audits until the contractor’s corrective actions are confirmed by

the auditors.

adequate in part

eRairetirCnoinipo AACD sultant actions

Low

High

Supervisors of the DCAA internal control audits we reviewed dropped

auditor findings of significant deficiencies from the audit reports or

treated them as suggestions for improvement without adequate support,

including instances of FAR noncompliance that should have been reported

as material weaknesses. In some cases, auditors reported “inadequate-in

part” opinions when the severity of the deficiencies or material

weaknesses identified would have called for “inadequate” opinions.

On December 19, 2008, DCAA revised its policy to eliminate the

“inadequate-in-part” opinion and the requirement to report suggestions for

improvement.

45

The new DCAA policy defines “significant

deficiency/material weakness” as an internal control deficiency that

(1) adversely affects the contractor’s ability to initiate, authorize, record,

process or report government contract costs in accordance with

applicable government contract laws and regulations; (2) results in a

reasonable possibility that unallowable costs will be charged to the

government; and (3) the potential unallowable cost is not clearly

immaterial. The new DCAA policy also establishes new guidance on

45

DCAA, “Audit Guidance on Significant Deficiencies/Material Weaknesses and Audit

Opinions on Internal Control Systems,” 08-PAS-043R (Dec. 19, 2008).

Page 18 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

reporting audit opinions on contractors’ internal control systems. For

example, the new DCAA policy states that audit reports that identify any

significant deficiencies/material weaknesses in contractors’ internal

control systems will include opinions that the systems are “inadequate.”

The policy notes that the contractor’s failure to accomplish any control

objective tested in DCAA’s internal control audits will or could ultimately

result in unallowable costs being charged to government contracts, even

when the control objective does not have a direct relationship to charging

costs to government contracts. As an example, the policy notes the control

objective related to ethics and integrity is not directly related to charging

costs to government contracts, but that the contractor’s failure to

accomplish the control objective creates an environment that could

ultimately result in mischarging to government contracts.

By eliminating the “inadequate-in-part” opinion, the new policy does not

recognize different levels of severity and could unfairly penalize

contractors whose systems have less severe deficiencies by giving them

the same opinion—”inadequate”—as contractors having material

weaknesses or serious deficiencies that in combination would constitute a

material weakness.

At the time we finalized our draft report for DOD comment, DCAA had

rescinded 18 of the 33 audits of contractor internal controls that we

determined did not contain sufficient testing to meet GAGAS.

46

Unreliable

audit opinions on contractor internal controls pose a significant risk

because DCAA generally performs these audits on a 2- to 4-year cycle and

the audit results are relied on for several years to make decisions on

testing in various audits of contractor internal controls and cost-related

assignments. In response to our earlier investigation in November 2008,

DOD added DCAA audits not meeting professional standards to its list of

material weaknesses.

47

Table 2 provides details on five case studies that

are typical of the flawed internal control audits that we reviewed during

the course of our work. For more detail on the internal control audits we

reviewed, see appendix I.

46

Under its decentralized management environment, DCAA headquarters obtains field

office agreement to rescind audit reports that do not meet GAGAS.

47

DOD, Fiscal Year 2008 Agency Financial Report, Department of Defense (Washington,

D.C.: Nov. 17, 2008).

Page 19 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

Table 2: Summary of Five Selected Internal Control Audits

Case Region Audit type Case details

1 Western Billing system (2004)

• DCAA auditors inappropriately planned and performed a billing system audit of a

federally funded research and development center (grantee) with $1.5 billion in annual

funding. The grantee does not have a “billing system.”

• The grantee is funded by a line of credit, which provides for cash draws and

transaction reporting by the grantee’s accounting system.

• DCAA auditors spent 530 hours revising Single Audit Act cash management audit

documentation to address procedures required in DCAA’s standard audit program for

billing system internal controls and developed a billing system audit report, when the

auditors could have simply forwarded the results of work on the grantee’s cash

management system performed under the Single Audit Act to the federal agency’s

buying command.

• As a result of our review, DCAA reassessed the need to perform a billing system audit

for the grantee and determined that it would rely on the Single Audit reports in the

future.

2 Western Accounting system

(2004)

• This audit involving accounting controls for one of the five largest DOD contractors

working in Iraq was initiated in November 2003.

• In September 2005, after nearly 2 years of audit work, DCAA provided draft findings

and recommendations to the contractor that included 8 significant deficiencies in the

contractor’s accounting design and operation.

• The contractor objected to the findings, stating that the auditors did not fully

understand its new policies and procedures, which were just being developed for the

fast track effort in Iraq.

• Following the contractor’s objections, various supervisory auditors directed the

auditors to revise and delete some workpapers, generate new workpapers, and in one

case, copy the signature of a prior supervisor onto new workpapers making it appear

that the prior supervisor had approved a revised risk assessment.

• On August 31, 2006, after dropping 5 significant deficiencies and downgrading 3

significant deficiencies to suggestions for improvement, DCAA reported an “adequate”

opinion on the contractor’s accounting system without adequate audit evidence for the

changes.

• The interim audit supervisor, who instructed the lead auditor to copy and paste the

prior supervisor’s name onto key risk assessment workpapers, was subsequently

promoted to be the Western Region’s quality assurance manager where he served as

quality control check over thousands of audits, including those GAO reported on last

year.

• In April 2007, the Special IG for Iraq Reconstruction (SIGIR) reported that despite

being paid $3 million to complete the renovation of a building in Iraq, the contractor’s

work led to plumbing failures and electrical fires in a building occupied by the Iraqi

Civil Defense Directorate.

• DCAA rescinded the audit report on December 2, 2008.

Page 20 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

Case Region Audit type Case details

3 Eastern Billing system (2005)

• In May 2005, DCAA reported an inadequate-in-part opinion on the billing system

internal controls of a second of the five largest DOD contractors.

• After issuing the report, DCAA auditors helped the contractor develop policies and

procedures related to accounts receivable, overpayments, and system monitoring

before performing a required follow-up audit—a serious impairment to auditor

independence.

• In June 2006, DCAA reported an adequate opinion on the contractor’s billing system

internal controls, including the policies and procedures DCAA helped the contractor

develop.

• As a result of GAO’s review, DCAA rescinded the follow-up audit report on March 6,

2009.

4 Central Billing system

(2005)

• This audit, which was initiated in July 2005, covered a new billing system at a

business segment of another of the five largest DOD contractors. Although DCAA

considers new systems to be high-risk and requires increased testing, auditors

deleted key audit steps related to contractor policies and internal controls over

progress payments from the standard audit program without explanation and

performed little or no testing of the contractor’s billing controls.

• The contractor objected to requests for documentation to test whether billing clerks

had received necessary training.

• One auditor told GAO he did not perform other tests because “the contractor would

not appreciate it.”

• The auditors provided draft findings and recommendations to the contractor in

February 2006 that included six suggestions to improve the system related to the

need for internal audits, oversight of subcontractor accounting systems, and

improvements in policies and procedures and desk instructions.

• Instead of issuing the report, when audit work was completed and noting the status of

any contractor actions to address identified control weaknesses, the auditors

monitored contractor corrective actions for 7 months, dropping the two suggestions for

improvement related to internal audits and monitoring subcontractor accounting

systems. The failure to monitor subcontractor accounting systems should have been

considered a significant deficiency.

• On September 15, 2006, DCAA reported an “adequate” opinion on the contractor’s

billing system.

• Following GAO’s review of this audit, DCAA rescinded the audit report on February

10, 2009.

Page 21 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

Case Region Audit type Case details

5 Central Billing system (2006)

• A fraud investigation by the Army’s Criminal Investigative Division was under way at

the time DCAA performed this contractor’s billing system audit. The FAO was aware

of the substance of the Army’s investigation.

• The auditor requested increases in budgeted audit hours to perform increased testing

because of fraud risk and the contractor’s use of temporary accounts for charging

costs that had not yet been authorized by the contracting officer.

• The auditor drafted an “inadequate” opinion on the contractor’s billing system, which

was overturned by the supervisor and FAO manager.

• Despite a reported $2.8 million in fraud for this contractor, DCAA reported an

“inadequate-in-part” opinion related to 3 significant deficiencies in the contractor’s

billing system on August 31, 2005, and an “adequate” opinion on September 11,

2006, related to a follow-up audit.

• The auditor, whose performance appraisal was lowered for performing too much

testing and exceeding budgeted audit hours, was assigned to and then removed from

the follow-up audit. The auditor left DCAA in March 2007.

• Following GAO’s review, DCAA rescinded both audit reports on November 20, 2008.

Source: GAO analysis of DCAA audit documentation and auditor interviews.

The 32 cost-related assignments we reviewed did not contain sufficient

testing to provide reasonable assurance that overpayments and billing

errors that might have occurred were identified. As a result, there is little

assurance that any such errors, if they occurred, were corrected and that

related improper contract payments, if any, were refunded or credited to

the government. Contractors are responsible for ensuring that their

billings reflect fair and reasonable prices and contain only allowable costs,

and taxpayers expect DCAA to review these billings to provide reasonable

assurance that the government is not paying more than it should for goods

and services. Further, we found that DCAA does not consider some cost-

related assignments to be GAGAS audits, even though these assignments

are used to provide assurance of the reasonableness of contractor billings,

for example:

Cost-Related

A

ssignments

Paid voucher reviews. DCAA performs annual testing of paid vouchers

(invoices) to determine if contractor voucher preparation procedures are

adequate for continued contractor participation in the direct-bill

program.

48

Under the direct-bill program, contractors may submit their

invoices directly to the DOD disbursing officer for payment without

further review. Although DCAA does not consider its reviews of contractor

48

DCAA does not perform paid voucher reviews during the year that it performs an audit of

the contractor’s billing system internal controls.

Page 22 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

paid vouchers to be GAGAS engagements; it has not determined what

standards, if any, apply to these assignments. In addition, for the 16 paid

voucher assignments we reviewed, we found that DCAA auditors failed to

comply with CAM guidance.

49

Rather than documenting the population of

vouchers, preparing sampling plans, and testing a random (statistical)

sample, auditors generally did not identify the population of vouchers, did

not create sampling plans, and made a small, nonrepresentative selection

of as few as one or two invoices for testing to support conclusions on their

work. Even when DCAA auditors tested 20 or 30 invoices, they did not test

billing controls or review supporting documentation for goods and

services purchased. Instead, the auditors performed limited procedures

such as determining whether the vouchers were mathematically correct

and included current and cumulative billed amounts. Based on this limited

work, the auditors concluded that controls over invoice preparation were

sufficient to support approval of the contractors’ direct billing privileges.

However, the limited work performed does not provide assurance that

contractor billings are accurate and comply with applicable laws, the FAR,

CAS, and contract terms. This is of particular concern because we

determined that Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS)

certifying officers rely on DCAA voucher reviews, and they do not repeat

review procedures they believe to be performed by DCAA.

Professional literature contains guidance to help auditors determine the

level of testing that should be performed to obtain sufficient, appropriate

evidence to support a conclusion that internal controls are effectively

designed, implemented, and operating effectively. Inquiry alone does not

provide sufficient, appropriate evidence to support a conclusion about the

effectiveness of a control. Some of the factors that affect the risk

associated with a control include

• the nature and materiality of misstatements that the control is intended

to prevent,

• the inherent risk associated with the related account(s) and

assertion(s),

• whether there have been changes in the volume or nature of

transactions that might adversely affect control design or operating

effectiveness,

49

CAM 6-1007.

Page 23 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

• the degree to which the control relies on the effectiveness of other

controls (i.e., information technology controls),

• the competence of personnel who perform the control or monitor its

performance, and whether there have been changes in key personnel

who perform the control or monitor performance, and

• whether the control relies on performance by an individual or is

automated (an automated control would generally be expected to be

lower risk if relevant IT general controls are effective).

50

Professional standards

51

state that the auditor should focus more attention

on the areas of highest risk. As the risk associated with the control being

tested increases, the evidence that the auditor should obtain increases. In

addition, the GAO/PCIE Financial Audit Manual provides guidance on

sampling control tests that would be relevant to DCAA testing of

contractor invoices.

52

The auditor should assess risk in determining the

control attributes to be tested and select a sample that the auditor expects

to be representative of the population. Attribute sampling requires random

or systematic, if appropriate, selection of sample items without

considering the transactions’ dollar amount or other special

characteristics. To determine the sample size, the auditor uses

professional judgment to determine three factors—confidence level,

53

tolerable rate (maximum rate of deviations from the prescribed control

that the auditor is willing to accept without altering the preliminary

control risk), and expected population deviation rate (expected error

rate).

54

50

AU § 350.19 and SSAE §§15.64 and 15.69.

51

AU §§ 350.07 through 350.14.

52

GAO-08-585G, § 450.

53

Confidence interval is the probability associated with the precision, that is, the

probability that the true misstatement is within the confidence interval.

54

For example, for a confidence level of 90 percent and a tolerable rate of 5 percent, a

sample size of 45 transactions would have an acceptable number of deviations of zero and

a sample size of 78 transactions would have an acceptable number of deviations of one. For

the same confidence level of 90 percent and a tolerable rate of 10 percent, a sample size of

45 would have an acceptable number of deviations of one and a sample size of 78 would

have an acceptable number of deviations of four.

Page 24 GAO-09-468 DCAA Audit Environment

Finally, the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA)

Audit and Accounting Guide: Audit Sampling

55

(Audit Guide) contains

attestation guidance on the application of SSAEs in specific

circumstances, including engagements for entities in specialized

industries. The Audit Guide states that an auditor using nonstatistical

sampling is not required to compute the sample size using statistical