I

NNOCENT

B

YSTANDERS

?

M

ONETARY

P

OLICY AND

I

NEQUALITY IN THE

U.S.

Olivier Coibion Yuriy Gorodnichenko

UT Austin

and NBER

U.C. Berkeley

and NBER

Lorenz Kueng John Silvia

Northwestern University

and NBER

Wells Fargo

This Draft: February 17

th

, 2016

Abstract: We study the effects of monetary policy shocks on—and their historical

contribution to—consumption and income inequality in the United States since 1980 as

measured by the Consumer Expenditures Survey. Contractionary monetary policy

systematically increases inequality in labor earnings, total income, consumption and total

expenditures. Furthermore, monetary policy shocks account for a non-trivial component

of the historical cyclical variation in income and consumption inequality. Using detailed

micro-level data on income and consumption, we document some of the different

channels via which monetary policy shocks affect inequality, as well as how these

channels depend on the nature of the change in monetary policy.

Keywords: Monetary policy, income inequality, consumption inequality.

JEL codes: E3, E4, E5.

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Global Interdependence Center and are grateful to

Stefania Albanesi, Jihad Dagher, Pierre Jaillet, Ricardo Reis, Aysegul Sahin and anonymous referees for

comments. We thank Peter Ireland for sharing his data. The views in the paper are those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent those of Wells Fargo.

1

I Introduction

With the level of income inequality in the U.S. rising to record levels in recent years, popular

concern with this question has grown, as illustrated for example by the Occupy Wall Street

movement. The topic of inequality has even breached the walls of the central banking community,

and a number of monetary policymakers have departed from their traditional focus on aggregate

considerations to discuss the potential distributional effects of monetary policy actions (Mersch 2014,

Bullard 2014, Forbes 2015, Bernanke 2015). But how even typical monetary policy decisions, much

less quantitative easing or forward guidance, affect economic inequality is a priori ambiguous

because of the number of channels through which these actions affect agents. In this paper, we show

that contractionary monetary policy shocks by the Federal Reserve have historically been followed

by persistent increases in income and consumption inequality and provide evidence on some of the

channels underlying these distributional consequences of monetary policy.

One channel that can generate heterogeneous effects of monetary policy on income is the

income composition channel, i.e. the fact that there is heterogeneity across households in terms of their

primary sources of income. While most households rely primarily on labor earnings, others receive

larger shares of their income from business, financial or transfer income. To the extent that monetary

policy affects these different forms of income in a heterogeneous manner (and it does), then different

types of households will experience different income outcomes. For example, richer households tend to

receive relatively more business income, and since the latter tends to rise relative to wages after

expansionary monetary shocks, this effect would tend to increase income and consumption inequality.

A second channel is the financial segmentation channel: if some agents frequently trade in financial

markets and are affected by changes in the money supply prior to other agents, then an increase in the

money supply will redistribute wealth toward those agents most connected to financial markets, as in

Williamson (2009) and Ledoit (2009). If agents participating actively in financial trades have higher

income and consumption on average than unconnected agents, then this channel implies that

consumption inequality should rise after expansionary monetary policy shocks. An additional channel

pushing in the same direction is the portfolio channel. If low-income households tend to hold relatively

more currency than high-income households (Erosa and Ventura 2002, Albanesi 2007), then

inflationary actions on the part of the central bank would represent a transfer from low-income

households toward high-income households which would tend to increase consumption inequality.

Two other channels, however, will tend to move inequality in the opposite direction in response

to expansionary monetary policy actions. The first is the savings redistribution channel: an unexpected

increase in interest rates or decrease in inflation will benefit savers and hurt borrowers as in Doepke

2

and Schneider (2006), thereby generating an increase in consumption inequality (to the extent that

savers are generally wealthier than borrowers). The second is the earnings heterogeneity channel.

Labor earnings are the primary source of income for most households and these earnings may respond

differently for high-income and low-income households to monetary policy shocks. This could occur,

for example, if unemployment disproportionately falls upon low income groups, as documented in

Carpenter and Rogers (2004). Similar effects could arise among the employed due to different wage

rigidities across the income distribution (e.g. from unionization in production but not management),

varying degrees of complementarity/substitutability with physical capital depending on agents’ skill

sets, or different endogenous labor supply responses from household-specific characteristics which

differ across the distribution. Heathcote et al. (2010), for example, document that the labor earnings at

the bottom of the distribution are most affected by business cycle fluctuations. The income composition

channel could also push toward reduced—rather than increased—inequality after expansionary

monetary policy since low-income households receive, on average, a larger share of their income from

transfers (e.g. unemployment benefits, food stamps) and transfers tend to be countercyclical.

In short, these different channels imply that the effect of monetary policy on economic

inequality is a priori ambiguous. As a result, we turn to the data to assess whether U.S. monetary

policy has contributed to historical changes in consumption and income inequality in the U.S., and if

so, through which channels. To do so, we study the dynamic responses of measures of consumption

and income inequality to monetary policy shocks identified as in Romer and Romer (2004). Our

measures of inequality come from detailed household-level data from the Consumer Expenditures

Survey (CEX) since 1980. These data are available on a higher frequency (quarterly) than other

sources such as IRS data employed by Piketty and Saez (2003), which is necessary to analyze the

effects of monetary policy shocks. While the CEX does not include the very upper end of the income

distribution (i.e. the top 1%) which has played a considerable role in income inequality dynamics

since 1980 (CBO 2011), the detailed household-level data do allow us to consider a wide range of

inequality measures for labor income, total income, consumption and total expenditures.

Using these measures of inequality, we document that monetary policy shocks have

statistically significant effects on inequality: a contractionary monetary policy shock raises the

observed inequality across households in income, labor earnings, expenditures and consumption.

These results are robust to the time sample, such as dropping the Volcker disinflation period or all

recession quarters, with only earnings inequality displaying some sensitivity. They are also largely

invariant to controlling for household size and other observable household characteristics such as

age, education and family size. The effects are economically large for consumption and expenditure

3

inequality, and moderate for total income inequality, but the effects on earnings inequality are much

smaller. Given the historical sequence of identified monetary policy shocks, these shocks appear to

have played a non-trivial role in accounting for cyclical fluctuations in some forms of inequality over

this period. While the contribution of monetary policy shocks to labor earnings inequality is virtually

nil in forecast error variance decompositions, it is approximately 10 percent for total income at

longer horizons and over twenty percent for consumption and expenditure inequality. Furthermore,

monetary policy shocks can account for a surprising amount of the historical cyclical changes in

income and expenditure inequality, particularly since the mid-1990s.

The fact that overall labor earnings inequality responds little to monetary policy shocks masks

some underlying distributional heterogeneity. After a contractionary monetary policy shock, upper

income households (90

th

percentile) see their labor incomes rise on average relative to the median

household, but so do low income households (10

th

percentile), at least temporarily. This leads to a

widening of the earnings distribution at the upper tail but a condensing of the distribution at the lower

tail, i.e. the earnings distribution becomes more skewed as in Guvenen et al. (2014). There is therefore

evidence for the earnings heterogeneity channel, even though its effects on the second moments of the

distribution are very small.

The effects of monetary policy shocks on total income inequality are larger, a feature which

appears to primarily reflect the income composition channel. We find that the incomes of households

at the 90

th

percentile rise somewhat relative to the median household, while households at the 10

th

percentile see their relative incomes fall particularly sharply. This is consistent with the fact that low

income households receive a much larger share of their income from transfers than labor earnings

than other groups, and real wages rise relative to transfers after monetary shocks. We also find that

financial income rises sharply after monetary policy shocks. Because the top 1% of the income

distribution receive a disproportionate share of their income from financial income (CBO 2011), our

baseline results on income inequality are most likely a lower bound since they exclude the top 1%.

The effects on consumption and expenditure inequality are larger still. But unlike the

heterogeneity in income inequality, heterogeneity in consumption and expenditure is driven primarily

by the upper end of the distribution: those at the 90

th

percentile see a much larger rise in consumption

and expenditures relative to the median household than the relative decline seen by those at the 10

th

percentile. In fact, the relative changes in consumption at the upper end of the distribution are

significantly larger than their relative changes in income, which suggests that portfolio, savings

redistribution and/or financial segmentation channels must also play some role.

4

Because the CEX does not include reliable measures of household wealth, it is difficult to

identify these channels. For example, in the absence of consistent measures of the size of household

currency holdings or financial market access in the CEX, we cannot directly quantify the specific

(money holding) portfolio channel emphasized by Albanesi (2007) or the financial market

segmentation channel in Williamson (2009). Nonetheless, to the extent that both channels imply that

contractionary monetary policy shocks should lower consumption inequality, the fact that our baseline

results go in the opposite direction suggests that these channels, if present, must be relatively small.

However, in the case of the savings redistribution channel, we provide evidence of wealth transfers by

identifying high and low net-worth households following the characterization of Doepke and Schneider

(2006), namely that high net-worth households are older, own their homes, and receive financial

income while low net-worth households are younger, have fixed-rate mortgages and receive no

financial income. We find that while the average responses of total income and labor earnings are

broadly similar across the two groups, consumption and, to a lesser extent, total expenditures rise

significantly more for high net-worth households than low net-worth households after contractionary

policy shocks.

Finally, we consider the sensitivity of these results to the nature of the monetary policy

innovation. Specifically, we focus on changes in the Fed’s inflation target, identified either as in

Coibion and Gorodnichenko (2011) or as in Ireland (2006). Permanent decreases in the inflation target

are also associated with higher levels of labor earning, total income, expenditure and consumption

inequality. While historical changes in the Fed’s inflation target account for a smaller fraction of the

forecast error variance than broader measures of monetary shocks for each form of inequality, changes

in the inflation target can account for the vast majority of the dynamics of inequality over the early to

mid-1980s, indicating that the Volcker disinflation period likely played a particularly important role in

accounting for the evolution of economic inequality during this time period.

Monetary policy therefore may well have played a more significant role in driving recent

historical inequality patterns in the U.S. than one might have expected. These results are noteworthy

for several reasons. First, the potential contribution of monetary policy to inequality has received

relatively little attention in the economics literature (Romer and Romer (1998) is an early exception).

Understanding and quantifying the sources of inequality is a first step to determining what kinds of

policies, if any, are most appropriate to address it. Second, the heterogeneity in consumption and

income responses across households, as well as the channels underlying them, are of immediate

relevance to monetary economists and policymakers for understanding the monetary transmission

mechanism. In addition, some research has linked rising inequality to credit booms and financial

5

crises (e.g. Rajan 2010, Kumhof et al. 2015), therefore suggesting a potential link from inequality to

macroeconomic stability. Third, there is a growing macroeconomics literature integrating

heterogeneous agents and distributional effects into New Keynesian models to revisit optimal fiscal

and monetary policy design.

1

Our results provide a rich set of stylized facts about the conditional

responses of income, earnings and consumption patterns across households to monetary policy shocks

that can be used to calibrate and differentiate between different classes of heterogeneous agent

models, in the same spirit as the use of monetary policy shocks by Christiano et al. (2005) to estimate

the parameters of New Keynesian models. Finally, recent work (e.g. Heathcote et al. 2010) has

emphasized not only the cyclical component to economic inequality but also the variation in

inequality across business cycle episodes. With changes in monetary policy having been proposed as a

potential contributor to the Great Moderation (e.g. Clarida et al. 2000), one can naturally consider

monetary policy as also affecting cyclical inequality patterns.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the Consumer Expenditure Survey, the

construction of inequality measures and their unconditional properties. Section 3 presents the main

results on the effects of monetary policy shocks on income, labor earnings, expenditure and

consumption inequality. Section 4 assesses the wealth effects of monetary policy shocks while

section 5 considers the implications of changes in the inflation target. Section 6 concludes.

II Measuring Inequality

In this section, we briefly describe the Consumer Expenditure Survey and the construction of

measures of inequality for total income, wage income, consumption and total expenditures.

2.1 The Consumer Expenditure Survey

The Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX) is the most comprehensive data source on household

consumption in the U.S. and is used for constructing weights of the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The

CEX, which is provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), consists of two separate surveys:

the Interview Survey and the Diary Survey. In this study we only use data from the Interview Survey

since the Diary Survey covers only expenditures on small items that are frequently purchased, mostly

related to food. The Interview Survey provides information on up to 95% of the typical household's

consumption expenditures. The CEX is a monthly rotating panel, where households are selected to be

representative of the US population, and is available on a continuous basis since 1980. About 1,500-

1

Examples include Gornemann et al. (2014), Guerrieri and Lorenzoni (2015), Luetticke (2015), Auclert (2016),

Kaplan et al. (2016), and McKay and Reis (2016).

6

2,500 households are surveyed in any given month. Each household is interviewed once per quarter,

for at most five consecutive quarters, although the first interview is used for pre-sampling purposes

and is not available for analysis. In each interview, the reference period for expenditures covers the

three months prior to the interview month. However, the within-interview variation is much lower

than the between-interview variation because the BLS processes many individual expenditure

categories assigning a third of the reported spending to each of the three months. Moreover, many

households also seem to smooth their reported three-month expenditures equally over the three

months. While these three-monthly periods do not coincide with calendar quarters and monthly

spending can include information from periods outside a given calendar quarter, we aggregate

monthly expenditures into quarterly expenditures to maximize the size of the sample and thus reduce

sampling error in the resulting series as well as to make the resulting series conformable with other

macroeconomic variables. In robustness checks, we explore alternative aggregation approaches and

find similar results. In short, “household time” is quarterly.

We define household consumption as the sum of non-durables (e.g. food and gasoline),

services, and expenditures on durable goods (e.g. furniture, jewelry). We also construct a broader

measure of household expenditures by adding mortgage and rent payments, health expenditures,

education spending and other expenses to household consumption levels.

2

As recommended by the

BLS, we sum expenditures that occur in the same month but are reported in different interviews.

Income data is asked in the first and last interview, and financial data is only asked in the last interview.

The reference period for income flows covers the twelve months before the interview. All nominal

variables are deflated using the CPI-U and survey sample weights are consistently applied. To reduce

the influence of outliers, we winsorized income and spending variables at bottom and top 1 percent.

3

Much work has been devoted to assessing the quality of the CEX relative to other data.

Heathcote et al. (2010), for example, compare income inequality data in the CEX with equivalent

measures from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and the Current Population Survey

(CPS). They find strong comovement among pre-tax earnings inequality measures from all three

surveys. Attanasio (2003) and Attanasio et al. (2004) similarly document the consistency of wage

inequality in the CEX and the CPS. More concern has been raised with respect to underreporting of

2

We correct sample breaks due to slight changes in the questionnaire of the following variables: food at home

(1982Q1-1988Q1), personal care services (2001Q2), and occupation expenditures (2001Q2). To further improve the

quality of the data, we drop the following observations: interviews with more or less than three monthly

observations; households reporting zero food or total expenditures; and observations with negative expenditures

where there should not be any.

3

See Appendix B for more details on how we process CEX data.

7

consumption in the CEX. For example, Krueger et al. (2010), Aguiar and Bils (2015) and Attanasio

et al. (2012) document that the CEX underreports consumption relative to aggregate data and that

this underreporting has become more severe over time. On the other hand, Bee et al. (2012) compare

reported consumption spending data in the CEX to comparable data from the national income

accounts data and find that the CEX data conform closely to aggregate data for large consumption

categories. For our purposes, the potential underreporting of consumption in the CEX is less of a

concern, since we will focus on cyclical fluctuations in consumption inequality. In addition, our

empirical specifications will focus on changes in inequality rather than levels. Nonetheless, the

potential limitations in the quality of the CEX survey data are an important caveat to bear in mind.

2.2 Measures of Inequality

Given the availability of household data on both consumption and income, the CEX allows us to

study the behavior of both forms of inequality. To do so, we focus on three ways of measuring each

form of inequality: Gini coefficients of levels, cross-sectional standard deviations of log levels, and

differences between individual percentiles of the cross-sectional distribution of log levels.

4

The Gini

coefficient has long been used to measure inequality and summarizes the extent to which a variable is

equally allocated across different components of the distribution. In addition, we will also use the

cross-sectional standard deviation of log values. Taking logs diminishes the sensitivity to outliers but

requires us to drop observations equal to zero, in contrast to the Gini coefficient. Finally, we use the

difference between the 90

th

percentile and the 10

th

percentile of the log levels in each distribution,

which also requires the elimination of observations with values of zero. However, the percentile

differential is less sensitive to extreme observations in the tails of the distributions.

Given the detailed data in the CEX, we will consider two forms of inequality for income and

consumption each. On the income side, we first construct measures of labor earnings inequality

across households. Given the survey nature of the data, the advantage of labor earnings is that they

are likely to be known with the highest precision by households relative to other forms of income.

The disadvantage is that labor income is only one component of most households’ income. As a

result, we also construct measures of total income inequality based on labor earnings as well as

4

All of our baseline measures of inequality are raw, i.e. do not control for any household characteristics like the

number of household members, age, education, etc. This is because some of the channels by which monetary policy

might affect inequality could be systematically related to some of these observables. For example, the redistribution

of wealth from borrowers to savers should likely be related to the age of households. Controlling for age would

make it more difficult to identify this kind of channel. Similar logic applies to other household characteristics.

However, while our baseline measures do not control for any household observables, we consider a number of

robustness checks in which we do control for household characteristics.

8

financial income, business income and transfers for each household. Because individuals in the CEX

are asked about their income only in the first and last quarters of their participation in the survey and

the BLS imputes income for periods in between, we use only those individuals who are reporting

their income in each survey to construct measures of income and earnings inequality. Hence, the

sample used to construct income inequality measures each quarter is only a subset of the total

population in the survey that period. We will focus primarily on pre-tax measures of total income,

although we also present after-tax income inequality measures and show that our results are robust to

this alternative measure.

5

Appendix Table 1 reports correlations among the different measures of

inequality for both income and labor earnings: all correlations are quite high, with those for income

being 0.89 or above over the entire sample from 1980Q1 to 2008Q4.

Similarly, we construct both a narrow and broad measure of consumption inequality. The

narrow measure, which we refer to as consumption inequality, includes the same categories as in

Parker (1999). Consumption goods in this category include non-durables, services, and some durable

goods (household appliances, entertainment goods like televisions, furniture) but do not include large

durable purchases such as house and car purchases. We also define a broad measure of consumption,

which we refer to as total expenditures and which includes the previous definition of consumption as

well as mortgage payments, purchases of cars, medical supplies and services, and tuition and books

for schooling among others. In contrast to income measures, consumption and expenditure data for

individuals in the survey is measured every survey wave, so consumption and expenditure inequality

measures use the entire population in the survey each period subject to the caveats discussed in

section 2.1. For both consumption and expenditures, we aggregate all reported purchases within each

definition at the household level, then construct inequality measures across households. Appendix

Table 1 documents high correlations across measures of expenditure inequality, ranging from 0.75 to

0.89. Correlations among the consumption measures are slightly smaller, ranging from 0.79 to 0.43.

2.3 Unconditional Properties of Inequality Measures

Figure 1 plots the historical inequality measures of income, labor earnings, expenditures and

consumption inequality measures from the CEX based on the cross-sectional standard deviation

(Panel A), Gini coefficient (Panel B) and the 90

th

to 10

th

percentile differential (Panel C), averaged

over the previous and subsequent quarter to illustrate more clearly business cycle and low-frequency

variations. Consistent with results documented in the literature (Krueger and Perri 2005), our

5

Following Kueng (2012) we compute tax burdens using the TAXSIM calculator of the NBER; see Feenberg and

Coutts (1993). The code is available at http://www.nber.org/~taxsim/to-taxsim/cex-kueng.

9

measures of total income inequality are all trending up over time. A similar pattern occurs for labor

earnings inequality when measured using the Gini coefficient but not when measured using the cross-

sectional standard deviation nor the 90

th

– 10

th

percentile differential, a feature of the data also

documented in Heathcote et al. (2010). There is a sharp increase in all forms of inequality in the early

1980s. Income inequality rises over the course of the 1990s but not consumption or expenditure

inequality measures. Finally, there is a noticeable decline in expenditure inequality over the course of

the 2000s despite there being no such decrease in income inequality.

The figures therefore reveal some evidence of cyclical behavior in inequality measures,

consistent with Heathcote et al. (2010). Table 1 presents unconditional correlations between

inequality measures and quarterly inflation, the unemployment rate and the Federal Funds rate. All

series are HP-filtered prior to measuring correlations so that the latter primarily reflect business cycle

fluctuations rather than trends. Correlations of different forms of inequality with the inflation rate are

very small and somewhat negative. Similar results obtain with interest rate correlations. Labor

earnings inequality is weakly positively correlated with the unemployment rate and negatively with

inflation. Expenditure and consumption inequality are more strongly negatively correlated with the

unemployment rate. This could be interpreted as being consistent with a wealth channel, whereby

even if income inequality varies little with the business cycle, cyclical fluctuations in asset prices

have significant effects on wealth holdings of individuals, leading to lower consumption and

expenditures of the wealthy during recessions.

6

Overall, however, the unconditional correlations do

not point toward very strong links between business cycles and inequality patterns.

III Effects of Monetary Policy Shocks on Inequality

In this section, we present baseline results for the effects of monetary policy shocks on measures of

income inequality. We first discuss the construction of monetary policy shocks, then present results

quantifying the effects of these shocks on different forms of inequality in the U.S., as well as number

of robustness checks. We also present results on how monetary policy shocks affect different

components of the distributions, whether mobility within the distribution changes after monetary

shocks, and the economic importance of monetary policy for inequality dynamics.

3.1 The Identification of Monetary Policy Shocks

6

Consistent with this, Parker and Vissing-Jorgensen (2009) document that consumption of high-income households

moves disproportionately with aggregate consumption.

10

To characterize the effects of monetary policy (MP) on inequality in the U.S., we follow Romer and

Romer (2004, RR henceforth) to identify innovations to monetary policy purged of anticipatory

effects related to economic conditions. RR first construct a historical measure of changes in the target

Federal Funds rate (FFR) at each FOMC meeting from 1969 until 1996. Using the real-time forecasts

of the Fed staff presented in the Greenbooks prior to each FOMC meeting (denoted by F), RR

construct a measure of MP shocks from the component of policy changes at each meeting that is

orthogonal to the Fed’s information set. Specifically, they estimate

where m denotes the FOMC meeting,

is the target FFR going into the FOMC meeting,

is the Greenbook forecast from meeting m of real output growth in quarters around meeting

m (-1 is previous quarter, 0 is current quarter, etc.),

are Greenbook forecasts of GDP deflator

inflation, and

are Greenbook forecasts of the current quarter’s average unemployment rate.

The estimated residuals !

are then defined by RR as MP shocks.

We extend the RR dataset on MP shocks until December 2008 as follows. First, we

incorporate more recent changes in the target FFR decided upon at regular FOMC meetings. Second,

we extend the Greenbook forecasts until December 2008, the most recent period through which the

Federal Reserve has released them. The dataset therefore extends until the zero-bound on interest

rates became binding in December 2008. Estimating the exact same specification as RR upon this

extended dataset since January 1969 yields a sequence of MP shocks at the frequency of FOMC

meetings. We then construct a quarterly measure of MP shocks by summing the orthogonalized

innovations to the FFR from each meeting within a quarter. Consistent with the results documented

in RR, the shocks are particularly large and volatile in the early 1980s during the Volcker disinflation

(Appendix Figure 1). The shocks also identify periods in which policy was more contractionary than

usual conditional on real-time forecasts. For example, the “pre-emptive strike” against inflation in

1994-1995 is visible as a period of consistently positive MP shocks, as is the 2005-2006 period. The

2000-2004 period, on the other hand, is identified as more expansionary than would have been

typical given staff forecasts of macroeconomic conditions, consistent with Taylor (2007).

Before turning to the effects of MP shocks on inequality, we first investigate how

contractionary monetary policy actions affect macroeconomic aggregates, financial variables, as well as

more detailed income and consumption aggregates. We follow Jorda (2005) and estimate the response

of economic variables to monetary policy shocks at different horizons h using local projection methods

11

"

#$%

"

#$%

&

%

'

%

("

#'

"

#'

)

*

'

%

#

++,

--.-

#$%

/ 012

3

where x is the variable of interest and the

#

++

are quarterly monetary policy innovations. With the

exception of interest rates, we use first-differences of macroeconomic variables in estimating (2) and

generate accumulated impulse responses to MP shocks from the estimated 4

5

%

6

%

7

.

7

As a

benchmark, we set J=2 and I=20. We estimate the system of equations across horizons jointly.

Standard errors are as in Driscoll-Kraay (1998) to allow for arbitrary serial and cross-sectional across

horizons and time. For each impulse response, we present one and 1.65 standard deviation

confidence intervals, as well as p-values for tests of the null hypothesis that the impulse response is

equal to zero for all horizons / 012. We consistently use H=20 quarters.

The results are presented in Figure 2 using data from 1969:Q3 to 2008Q4, the entire period over

which MP shocks are available. For comparability across specifications, we define the time sample based

on the time series of the dependent variable for horizon h=0. Over the entire sample, contractionary

monetary policy shocks lower real GDP and raise unemployment, and lower consumption. The reduction

in consumption obtains for both durables as well as non-durables and services.

8

These results conform to

the empirical literature on the effects of MP shocks (see Christiano et al. 1999 for a review).

In addition, we consider the effects of MP shocks on real housing prices (Case-Shiller price

index deflated by the GDP deflator), which are a particularly important component of household

wealth. Real housing prices, the major financial asset for many households, decline gradually after one

to two years, ultimately falling by 5% after a one hundred basis point shock to the FFR. This suggests

one channel through which monetary policy might affect households differently: to the extent that

households’ wealth is not allocated in the same manner across assets, then those households whose

wealth is particularly concentrated in their home would tend to experience very different wealth effects

than non-homeowners. Wong (2015) presents additional evidence in line with this channel.

Figure 2 also presents responses of different sources of income to contractionary MP shocks.

The response of real wages is not statistically different from zero over either sample, while business

income drops rapidly and significantly. Financial income, on the other hand, rises significantly. Total

7

It is conventional to assume that monetary policy shocks do not have contemporaneous effects on output, inflation,

etc. but may have contemporaneous effect on interest rates, etc. Consistent with this convention, we set the

contemporaneous effect for all variables (except the fed funds rate) to zero in the impulse responses reported in Figure

2. That is, we use 8

5

%

9 rather than 8

5

%

9 for all variables but fed funds rate. For fed funds rate, we use 8

5

%

9.

8

NIPA’s definitions of spending are different from our definitions of consumption/spending in the CEX. NIPA’s

non-durable consumption is the closest counterpart of our definition of consumption in the CEX. Appendix Table 13

documents that the response of non-durable consumption is similar to the response of CEX-based measure of

consumption. Thus, although there is a discrepancy in the aggregate levels of CEX and NIPA spending, the impulse

responses to monetary policy shocks are not necessarily different.

12

income from transfers drops over the first year after a shock before returning to its original level. Thus,

these results suggest that heterogeneity in income sources across households may also lead to important

distributional consequences to monetary policy actions.

9

Contractionary monetary policy will tend to

raise incomes for those who receive a lot of financial income but lower incomes for business owners.

3.2 The Effects of Monetary Policy Shocks on Inequality

To quantify the overall effects of MP shocks on economic inequality, we estimate a version of

equation (2) using inequality measures for total income, labor earnings, total expenditure and

consumption, defined as in section 2:

10

"

#$%

"

#$%

&

%

'

%

("

#'

"

#'

)

*

'

%

#

++,

--.-

#$%

/ 012:

3;

Note that we allow a contemporaneous response of inequality to monetary policy shocks because of

time aggregation in the CEX data (we discuss this more below and in Appendix A) and thus the

impulse response is given by 4

5

%

6

%

7

.

We do so for each form of inequality using three different measures of inequality for each: the

cross-sectional standard deviation (of logged values), the Gini coefficient, and the difference between

the (log) 90

th

percentile and the (log) 10

th

percentile. While MP shocks are generated regressors, Pagan

(1984) shows that if the null hypothesis is

%

0 for any / 012, then standard errors need no

adjustment. Furthermore, as discussed in Coibion and Gorodnichenko (2012a), explicitly adjusting

standard errors for the presence of generated regressors has negligible effects in this setting because the

shocks are the residuals from the first stage rather than the fitted values. Given the consensus view

among mainstream economists that monetary policy has played little role in affecting economic

inequality in the U.S., this is a reasonable null to hold. Furthermore, because MP shocks are the residuals

from estimates of equation (1), they will be largely orthogonal to contemporaneous economic conditions

and other factors absorbed into the error term in equation (2), further justifying the use of unadjusted

standard errors. In estimating equation (2) for inequality measures, we consistently use a lag structure of

< 3 and = 30 quarters, but show later that our results are insensitive to alternative lag structures.

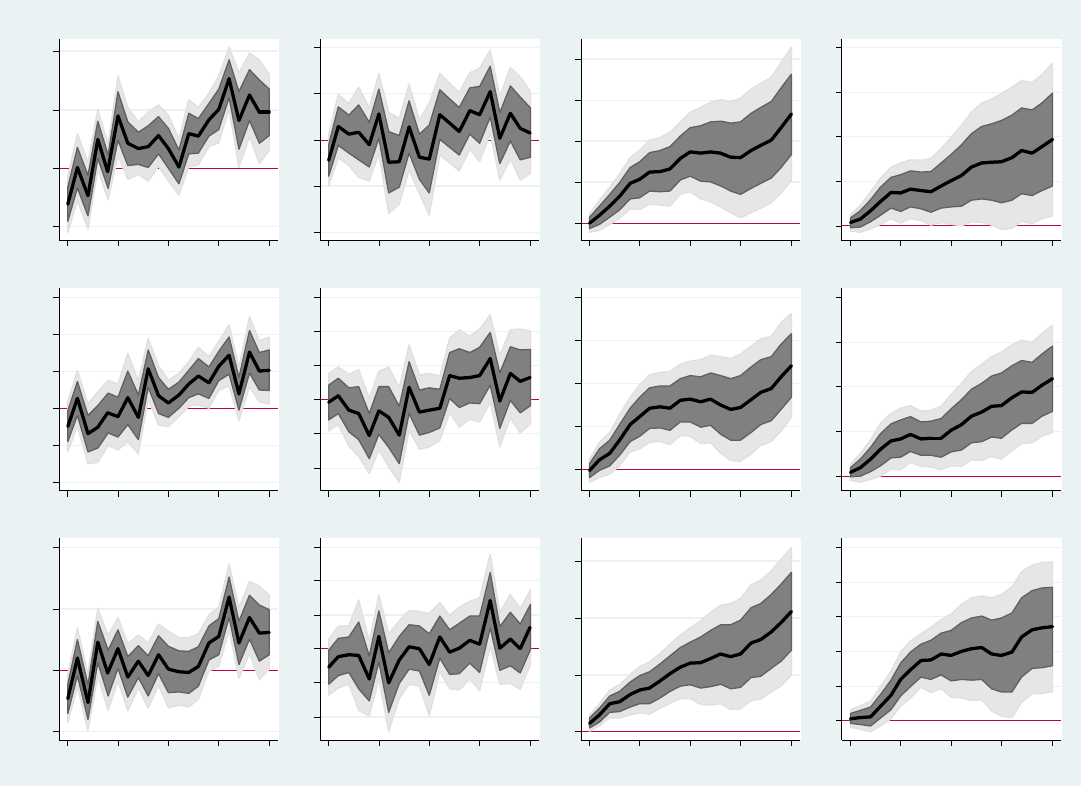

Figure 3 presents the accumulated impulse responses from estimates of equation (2) for each

form of inequality (income, labor earnings, expenditure and consumption) and measure of that

inequality (standard deviation, Gini, and 90

th

to 10

th

percentile differential) using data from 1980Q3

9

In Appendix Figure 2, we show that these differential responses of incomes also hold in the post-1980 period.

10

To ensure that changes in inequality are not driven by changes in the composition of CEX households over time,

we hold the set of households constant when we calculate changes in measures of consumption and expenditure

inequality from a given quarter to the next one.

13

until 2008Q4 and the associated one and 1.65 standard deviation confidence intervals. For each

response, we again report p-values for the test of the null hypothesis that monetary policy shocks

have no effect on each form of inequality across all (/ 0130) horizons. The results for both

income and labor earnings inequality point to statistically significant effects of MP shocks on

inequality. For total income inequality, the rise in inequality is somewhat delayed, occurring one to

two years after the shock depending on the specific measure. We can strongly reject the null of no

response in income inequality, both pointwise at longer horizons and across all horizons (p-values

<0.01). The results are almost identical if we use after-tax income inequality (Appendix Figure 3).

Furthermore, the quantitative responses are relatively large: a one hundred basis point increase in the

FFR leads to increases in income inequality that half of one standard deviation (Appendix Table 1).

With earnings inequality, the responses are less precisely estimated. Although we can still reject the

null of no response over the entire horizon and earnings inequality appears to be moderately higher

two to three years after the shock, the evidence for higher inequality in earnings after a

contractionary monetary policy shock is more tentative than it is for overall income inequality.

Strong and persistent effects of monetary policy shocks are consistent with other evidence for

the economic effects of these shocks. For example, Romer and Romer (2004) find that the maximum

effect of monetary shocks on GDP occurs two years after a shock and the effect remains significant

after then for quite some time. Coibion and Gorodnichenko (2012b) and others document that

monetary policy is extremely persistent so that a monetary shock is propagated for a long time. To

assess whether the strong response of inequality is plausible, we focus on the Volcker disinflation

when the experiment is perhaps as clear cut as one can get. The cumulative Romer-Romer shock over

1980-1984 is approximately 1.5 percentage points. The Congress Budget Office (2011, Figure 11)

estimates that the Gini coefficient for market income plus transfers increased by approximately 3

percentage points. Our estimates in Figure 3 suggest that given the cumulative size of the shock (1.5

percentage points), Gini inequality should have increased by approximately 1.5 percentage points for

income. Theoretical models are also consistent with these magnitudes. For example, the

heterogeneous agent model of Gornemann et al. (2014) implies that a one hundred basis point

increase in the federal funds rate should raise the income Gini by approximately 0.003 percentage

points, or around one-third of what we find, whereas the calibrated model of Luetticke (2015)

predicts a larger response of the income Gini of over 0.02 percentage points, or twice what we find.

Our estimates are therefore in line with both historical and theoretical magnitudes.

14

Turning to consumption and expenditure inequality, every measure of inequality points to a

statistically significant and highly persistent increase in inequality after a contractionary monetary

policy shock. Furthermore, the point estimates for expenditures are consistently larger than for other

forms of inequality, pointing to MP shocks having disproportionately large effects on expenditure

inequality relative to other forms of economic inequality. With the volatility of consumption and

expenditure inequality being significantly lower than that of income inequality (Appendix Table 1),

this translates into even larger economic effects: a one hundred basis point monetary policy shock

raises inequality in expenditures and consumption by approximately three standard deviations each.

11

In short, across all forms of inequality (with only earnings inequality being a possible exception) and

the different ways of measuring each type of inequality, the impulse responses indicate that

contractionary MP shocks are associated with higher levels of economic inequality.

12

3.2 Robustness

We consider a number of robustness checks on this benchmark result. First, we assess the sensitivity

of our findings to lag lengths in specification (2). Using fewer lags of monetary policy shocks has

little qualitative effect on the result, as illustrated in Appendix Figure 4 for the case of I=12. We also

consider using more lags of the dependent variable, setting J=4, which requires us to drop two

quarters in 1980. While this has little effect on the responses of income, expenditure and

consumption inequality, both the Gini and the 90-10 measures of earnings inequality now point

toward a brief decline in earnings inequality after contractionary monetary policy shocks (Appendix

Figure 5). To identify whether this reflects the addition of lags or the reduction in the time sample,

we re-estimate our baseline specification of (2) omitting the entire Volcker disinflation period (i.e.

starting in 1985Q1). Results for income, expenditure and consumption inequality are again largely

unaffected, but earnings inequality now briefly declines when measured using all three inequality

measures (Appendix Figure 6). This suggests that the rise in earnings inequality identified in the

11

The fact that the estimated response of income/earnings inequality is weaker than the estimated response of

consumption/expenditures need not indicate an inconsistency. First, income measures reported in CEX do not include

changes in valuation of assets. In other words, if valuation gains are not realized, they are not recorded in CEX.

Obviously, households can consume more in response to capital gains and thus consumption/expenditure responses can

be stronger. Second, consumption can be more volatile/disperse than current income because consumption can respond

to news about future income. For example, if the income process has positive correlation of growth rates (e.g. an

ARI(1,1) process), consumption will be more volatile than income because households want to start to consume against

their future income that is greater than the current income. Third, CEX survey questions about income refer to the

previous twelve months while consumption questions refer to more recent periods (the last three months or more

recent). Thus, a weak response in measures of income inequality may be a result of this CEX limitation.

12

We find similar results (Appendix Table 12) when we use monetary policy shocks identified from changes in fed

funds futures around FOMC announcements (see Gorodnichenko and Weber (2016) for more details on the

construction of these shocks).

15

benchmark results could be particularly sensitive to the Volcker disinflation period, a feature which

is not the case for the other inequality measures. In contrast, if we drop all recession periods from the

analysis, we find that the rise in earnings inequality is much more pronounced than in the baseline

case (Appendix Figure 7) while the results for other forms of inequality are again qualitatively

unchanged. Hence, while the rise in income, expenditure and consumption inequality after

contractionary monetary policy shocks appears to be remarkably robust, there is more sensitivity in

the response of earnings inequality to the specific time period included in the analysis.

As a second set of checks, we investigate whether our benchmark results are sensitive to

timing assumptions. Specifically, the survey questions in the CEX ask respondents to report their

spending for certain types of goods over the previous three months (other types of spending are

reported at the monthly frequency). The resulting 3-month spending for these types is allocated into

monthly spending by imputing a third of the 3-month consumption to each month that falls into the

given 3-month period. Because a third of participating households is surveyed in a given month, the

total level of spending in a given calendar quarter includes consumption that may occur in other

calendar quarters. As a result, time aggregation of these cohorts to the quarterly frequency can lead to

a temporal structure which does not conform to that used for monetary policy shocks. As shown in

Appendix A, this implies that our local projection approach will recover a smoothed average of the

underlying impulse response functions.

An alternative approach is to construct a different quarterly sequence of monetary policy

shocks to conform to the timing of each consumption within each cohort (A, B, and C), construct

inequality measures within each cohort, and then estimate the response of inequality as a system of

equations across cohorts and horizons:

>?

#$%

(@

A

)

%A

B

C

%

D

C

>?

#C

(@

A

)B

E

%

F

E

#E++

A

--.-

#%

A

>?

#$%

(@

G

)

%G

B

C

%

D

C

>?

#C

(@

G

)B

E

%

F

E

#E++

G

--.-

#%

G

>?

#$%

(@

H

)

%H

B

C

%

D

C

>?

#C

(@

H

)B

E

%

F

E

#E++

H

--.-

#%

H

for / 012, where we restrict the impulse responses to be the same across cohorts. We allow for

fixed effects which vary by cohort and horizon (γ). This alternative approach, described in more

detail in Appendix A, ensures that the timing of monetary policy shocks conforms to the timing of

16

consumption within each cohort. However, because the cross-section of each cohort is much smaller,

each inequality measure is now much noisier than our benchmark measures. As illustrated in

Appendix Figure 8, this alternative timing significantly reduces the precision of the estimates (as

expected from noisier measures of inequality) and leads to more transitory increases in consumption

inequality, but does not otherwise alter the qualitative result that contractionary monetary policy

shocks raise consumption and expenditure inequality.

Finally, we want to ensure that our results are robust to household characteristics. Our baseline

measures of economic inequality across households do not control for a number of household

characteristics such as number of people in the household, age of household members, education, etc.

Because work on inequality sometimes normalizes household income and consumption by the number of

individuals in the household, we also consider measures of income and consumption inequality across

households adjusted using an OECD equivalence scale.

13

The results (using the cross-sectional standard

deviations) are very similar to those in our baseline (Appendix Figure 9), with only the response of

consumption inequality being significantly smaller and more transitory than in the baseline.

We also consider measures of inequality after controlling for factors which would contribute to

differential income and consumption levels across households. For example, we control for age of the

head of household (quartic polynomial), the number of adults and the number of children in the

household, race, the education level of the head of household, and a number of other characteristics by

first regressing logged household income, earnings, consumption and expenditures on these observables.

Inequality is the cross-sectional standard deviation of the residuals across households (since Gini

coefficients cannot be constructed using residuals). Again, the estimates are qualitatively unchanged with

only the response of consumption inequality being significantly smaller (but still significantly positive).

In short, contractionary monetary policy shocks have a discernable effect on economic

inequality: they are followed by prolonged rise in income, consumption and expenditure inequality

and, to a lesser extent, a rise in labor earnings inequality.

3.4 Why Does Inequality Increase After Contractionary Monetary Policy Shocks?

The evidence in section 3.2 suggests that contractionary monetary policy actions raise consumption and

income inequality. We now investigate some of the mechanisms underlying this inequality response.

Specifically, we focus on the extent to which MP shocks affect consumption and income in the upper

and bottom ends of the distribution. To do so, we consider the responses of different percentiles of the

13

The OECD equivalence scale assigns a value of 1.0 to the head of the household, a value of 0.7 to each additional

adult (17+), and a value of 0.5 to each child.

17

consumption and income distributions to MP shocks. Because of the nature of the survey data, the way

these measures are constructed for income measures versus consumption measures are different. In the

case of both income and labor earnings, we construct percentiles each quarter from the distribution of

households reporting income and earnings that quarter. Since households are asked about their income

and earnings over the last twelve months in only the first and fourth quarter in which they participate in

the survey, these measures of different percentiles of the earnings and income distribution reflect a

changing composition of households each quarter. In contrast, because consumption and expenditures

are tracked each quarter, we can control for the potentially changing composition and ranking of

households across periods when we measure the changes in consumption and expenditures by

percentile each quarter. Specifically, in each quarter, we rank households according to either their

consumption or expenditures. Then, we isolate those households near each percentile of interest (90

th

,

50

th

, and 10

th

) that quarter and construct the percent changes in their consumption and expenditures.

Applying this procedure each quarter yields a time series of changes for each percentile controlling for

composition effects. We then look at how the difference between the 90

th

and 50

th

percentile of each

distribution responds to monetary policy shocks using equation (2) and do the same for the difference

between the 10

th

and 50

th

percentile of each distribution. We estimate the two sets of impulses

responses jointly for each form of inequality (income, earnings, expenditure and consumption) and test

the null hypothesis that the two are equal across all horizons (h=0,…,20).

Consistent with the absence of a strong response of earnings inequality as measured by the

difference between the 90

th

and 10

th

percentiles of the earnings distribution in Figure 3, we find

(Figure 4) only limited evidence of heterogeneity in labor earnings across the distribution after

monetary policy shocks. The difference between the 90

th

and 50

th

percentiles remains relatively close

to zero. Although we can reject the null that earnings responses of the 90

th

and 50

th

percentiles are

equal, the earnings of the 90

th

percentile rise only 1-2% relative to the median. The dynamics of the

difference between the 10

th

and the 50

th

percentiles are similar, so we cannot reject the null that the

two impulse responses are the same over the entire horizon. Thus, a contractionary monetary policy

shock is characterized by a widening of the earnings distribution above the median but a tightening

of the earnings distribution below the median, leading to only small effects (if any) on inequality as

measured by the difference between the 90

th

and the 10

th

percentile.

In contrast, we find more heterogeneity in total income responses. Incomes of those at the 90

th

percentile rise persistently relative to the median household while those at the 10

th

percentile see their

income decline relative to the median, especially at longer horizons. The behavior of total income of

90

th

percentile relative to the median follows fairly closely the pattern of labor earning differences, but

18

this is not the case for total incomes of the 10

th

percentile relative to the median. Appendix Table 2

presents a decomposition of total income for each quintile (measured by consumption of nondurables

and services as a proxy for permanent income). This decomposition illustrates the greater importance of

labor earnings as a share of total income at higher quintiles. In the 1990s, labor income accounted for

nearly 80% of total income for the highest quintile, but less than 40% for the bottom quintile. Instead,

the largest contributor to total income (approximately 50%) for those in the bottom quintile of the

distribution is the “other income” category, which includes unemployment insurance, Social Security

and pension payments, welfare, worker’s compensation, and other transfer programs. Even at the

second quintile of the distribution, other income accounts for approximately 25% of total income,

whereas this ratio is less than 10% for the top 2 quintiles. Financial and business income shares vary

much less across the distribution: the share of business income rises from 2% of total income for the

bottom quintile to 5-9% for the top quintile while financial income falls from a share of 11% at the

bottom quintile to approximately 8% for the top quintile. Because transfers fall relative to wages after

contractionary monetary shocks (by two percentage points when estimated over the whole sample and

by four percentage points over the post-1980 period), much of the relative decline in the total income of

lower income groups can be accounted for by their different composition of income.

With consumption and expenditures, we observe even more heterogeneity. Consumption and

expenditures of the 10

th

percentile decline relative to the median (we can reject the null that the

response is equal to zero at standard levels for each variable) by similar orders of magnitude as the

relative decline in their income. However, the consumption and expenditures of the 90

th

percentile rise

disproportionately relative to the median: by 10% for consumption and 15% for expenditures while

their relative incomes rise only by 2-3%. The increase in consumption and expenditure inequality

observed in Figure 3 after contractionary monetary policy shocks is therefore primarily driven by rising

expenditures and consumption of those at the top of the distribution, and only to a smaller extent falling

consumption and expenditures by those at the lower end of the distribution. One reason for these

patterns could be that different groups consume very different bundles of goods, especially if those at

the top of the distribution have more expenditures tied to interest rates. Appendix Table 3 provides a

decomposition of consumption and expenditures by households across quintiles, ranked by

consumption of non-durables and services each quarter, as well as information about their relative

expenditures on interest-sensitive expenditures.

14

While households in the upper end of the distribution

consume relatively more durables and devote more of their spending to interest-sensitive expenditures

14

Interest-sensitive expenditures are defined as mortgage payments, purchases of automobiles, spending on

education, spending on repairing houses and other real estate, and durable consumption goods.

19

like mortgage payments and auto purchases, the differences across quintiles are small. Hence, the

greater response of expenditures for those at the 90

th

percentile of the expenditure distribution after MP

shocks is unlikely to be explained via composition of spending across quintiles.

3.5 Distributional Mobility after Monetary Policy Shocks

A potential caveat to the responses of specific percentiles of income and consumption distributions to

MP shocks is that it is not clear to what extent households are moving across the distribution. To assess

mobility across the distribution, we construct time-varying quarterly transition probabilities for each

quintile of the consumption distribution. These are defined as the fraction of consumers within each

quintile who, in the next quarter, end up in another quintile. Figure 5 plots the time-varying transition

frequencies of households staying within the same quintile of the consumption distribution from 1980Q1

until 2008Q4. One notable feature of these time series is that mobility has generally declined over time

for each quintile. For example, for the middle quintile, the frequency of remaining within that quintile

from one quarter to the next has gone from approximately 35% in 1980 to nearly 45% in 2008.

To assess whether MP shocks have significant effects on these transition frequencies, we

estimate equation (2) for each series measuring the probability of staying in the same quintile from

one quarter to another with squared monetary policy innovations as the shocks. The latter identify

whether MP shocks, be they positive or negative, lead to increased movements across the

distribution. Impulse responses, presented in Figure 5, point to little persistence in the effects of MP

shocks on transition probabilities: after two years, almost none of the estimates are different from

zero. At the same time, MP shocks cause increased movement within the distribution: the frequency

of households remaining within the same quintile declines for all quintiles. These results suggest one

reason why impulse responses for different percentiles of the total income and labor earnings

distribution appear so volatile over the first two years: there is significant movement within the

distribution in the quarters following MP shocks. However, as this increased mobility fades after two

years, the percentile responses converge to more stable outcomes. Consistent with this, percentile

responses of the expenditure and consumption distributions, which control for composition, are more

stable over the first two years than are those of the earnings and income distributions.

3.6 How Important Is The Contribution of Monetary Policy Shocks to Inequality?

In this section, we consider the extent to which MP shocks can account for the dynamics of income

and consumption inequality in the U.S. That is, whereas the previous section focused on

characterizing whether MP shocks affect inequality, we now turn to the question of assessing the

quantitative contribution of this relationship.

20

First, we consider the share of the variance in inequality which can be accounted for by MP

shocks over this time period. The fraction of the variance in inequality at different horizons accounted

for by MP shocks can be recovered directly from estimates of equation (2). This measure therefore

provides one metric of the extent to which MP shocks are quantitatively important in driving inequality

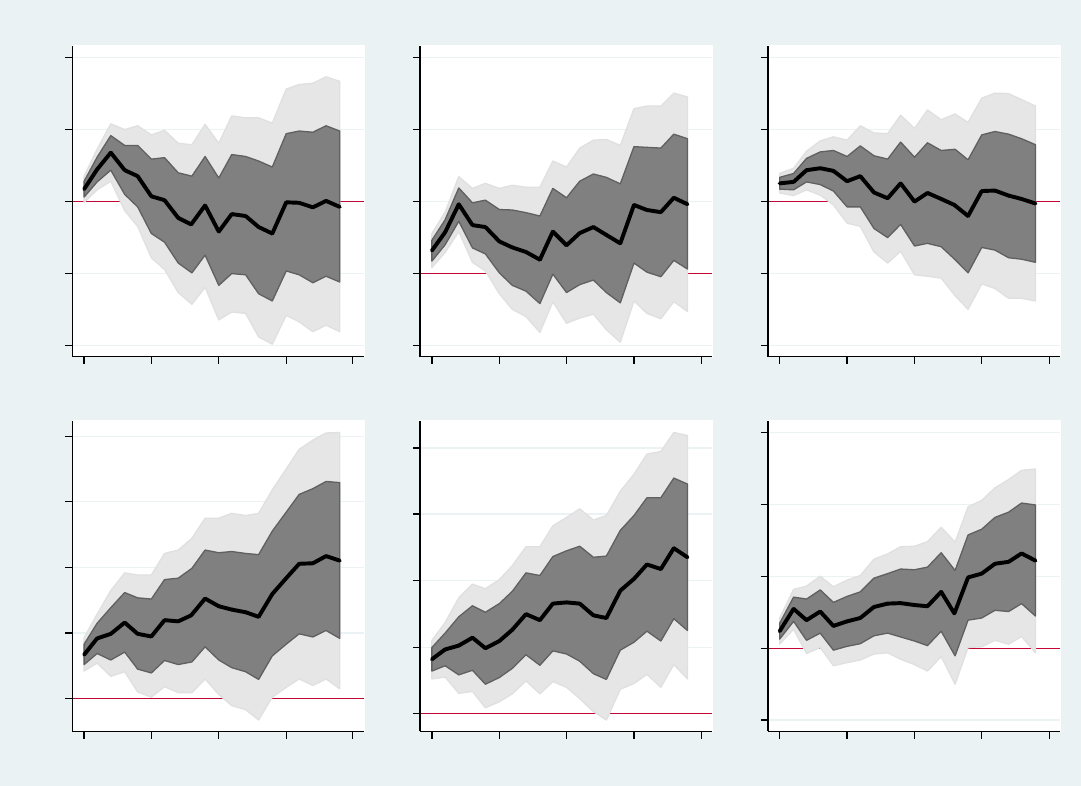

dynamics. Estimates from the variance decompositions are presented in Figure 6 for total income, labor

earnings, total expenditures, and consumption inequality. In line with the impulse responses, we find

that the quantitative contribution of monetary policy shocks to earnings inequality has been small, less

than 5% at all horizons of 5 years or less. But for other variables, monetary policy shocks have been

more important. With income and consumption inequality, monetary policy shocks account for 10-20%

of forecast error variance at longer run horizons, and an even larger share for expenditure inequality.

These magnitudes are in line with the contribution of monetary policy shocks to other macroeconomic

variables (Christiano et al. 1999) and are consistent with these shocks playing a non-trivial role in

accounting for U.S. inequality dynamics.

As a second way to assess whether the impulse responses of inequality are quantitatively

important, we consider the extent to which MP shocks since 1980 can account for the historical

variation in U.S. income and consumption inequality. Predicted changes in income, salary,

expenditure and consumption inequality due to MP shocks come from our estimates of equation (2).

We average both actual and predicted variables over the previous and subsequent quarter values to

downplay very high-frequency variation in inequality measures.

Figure 7 presents the results using the cross-sectional standard deviation measures of

inequality, with other measures yielding qualitatively similar results. First, monetary policy shocks

appear to account for very little of the variation in earnings inequality, consistent with the results of

the forecast error variance decomposition, except during the very early 1980s and to a lesser extent

the mid to late 1980s. This likely explains the sensitivity of the impulse responses of earnings

inequality to the inclusion of the Volcker disinflation discussed in section 3.2. In contrast, there is a

much higher correlation visible between predicted movements in income, consumption and

expenditure inequality driven by monetary policy shocks and actual changes in these variables

throughout the sample. While monetary policy shocks clearly cannot account for the trends in these

variables, these results do suggest that monetary policy changes have indeed played some role in

accounting for higher frequency movements in economic inequality in the U.S.

IV Wealth Redistribution in Response to Monetary Policy Shocks

21

While the previous section documented heterogeneity in labor income responses to MP shocks, as

well as heterogeneity in sources of income across individuals, discussion of the distributional effects

of monetary policy actions frequently focuses on three additional channels. First, if households hold

different portfolios and some financial assets are more protected against inflation surprises than

others, then monetary policy actions can, via their effects on inflation, cause a reallocation of wealth

across agents, as emphasized in Erosa and Ventura (2002) and Albanesi (2007). A second

redistributive channel stems from segmented financial markets: if some agents frequently trade in

financial markets and are affected by changes in the money supply prior to other agents who are less

involved in financial markets as in Williamson (2009), then contractionary MP shocks should

redistribute wealth from those connected to the markets toward the unconnected agents leading to

declining consumption inequality. Unfortunately, the CEX does not include reliable data on the cash

holdings of households nor does it include information that would allow us to identify which

households are most connected to financial markets, such as those working for the financial industry.

However, to the extent that both channels point toward contractionary MP shocks lowering

consumption inequality, the fact that our baseline results go precisely in the opposite direction

suggests that these channels, if present, must be significantly weaker than the labor earnings channel.

In addition, because monetary policy actions alter real interest rates in the short run, they will

have redistributive effects on savers and borrowers as in Doepke and Schneider (2006): since

contractionary policy shocks represent a transfer from borrowers (low net-worth) to savers (high net-

worth), one might expect to see disproportionate increases in the expenditures of borrowers. While

the CEX does not include reliable data on the net wealth position of households, we can still assess

this channel by restricting our attention to households with those characteristics identified by Doepke

and Schneider (2006) as being closely associated with high net-worth and low net-worth households.

Specifically, they argue that the main losers from inflation are “rich, old households” while the main

winners are “young, middle-class households with fixed-rate mortgage debt.” In the context of the

CEX, we therefore restrict the sample to two groups: 1) low net-worth households are defined as

aged 30-40 year-old white households with a male head in the household, no financial income, and

positive mortgage payments, 2) high net-worth households are defined as aged 55-65 years white

households with a male head in the household, positive financial income, and no mortgage payments.

We restrict the first two categories to be white households with a male head in the household to limit

the possible sources of differences between the two categories without unduly restricting the number

of households in each group (as would be the case if we imposed restrictions on education levels).

22

For each set of households, we then construct measures of mean (log) income and expenditures

as well as subcategories of each. We then take the difference between the two groups and construct

impulse responses for the difference in levels using equation (2). The results, plotted in Figure 8, support

the redistribution of nominal wealth effect in generating heterogeneity in consumption. Labor earnings

of high net-worth households are, if anything, lower than those of low net-worth households after

monetary shocks but their incomes are modestly higher, approximately 0.5% on average. While their

relative expenditures rise by a proportional amount, their consumption is much higher: rising as much as

5% relative to low net-worth households. This disproportionate response of consumption, relative to

income, is consistent with a redistributive effect of monetary policy.

V Permanent Changes in Monetary Policy

In assessing the effects of MP shocks on inequality, we have followed the approach of Romer and

Romer (2004) because their identification procedure has a number of advantages over previous

attempts to do so. However, as emphasized by RR, their procedure is not designed to characterize the

reaction function of the Fed and therefore the identified innovations reflect a number of potential

sources: changing operating procedures, policymakers’ evolving beliefs about the workings of the

economy, variation in the Fed’s objectives, political pressures, and responses to other factors. Some

of these changes could be interpreted as innovations to the central bank’s policy rule (i.e. its

systematic behavior)—for example if a new Chairman dislikes inflation more than a previous one—

while others would more appropriately be characterized as transitory deviations from a policy rule

(for example, political pressures at the time of an election). RR deliberately do not attempt to

separate out these different sources to maintain as much variation in the shocks, but a caveat to this is

that different sources of shocks may yield very different economic responses. In particular, one might

expect permanent changes in monetary policy to have more pronounced effects than transitory

changes. If different forms of MP actions affect inequality differently, then using a composite shock

measure such as that of RR may understate the effects of monetary policy on inequality.

As a result, we want to assess whether similar qualitative results obtain using a narrower but

more persistent type of monetary policy action: changes in the Federal Reserve’s target rate of

inflation. Because of the inability to directly observe the historical inflation target of the Federal

Reserve, we consider two different estimates of this measure. First, following Coibion and

Gorodnichenko (2011), we posit a reaction function for the central bank:

I

#

( J

#

J

#

)K

#

--

#

L

M#

#

#$

N

#

OP#

#

Q

#

Q

N

N

N

N

R#

"

#

S

23

J

#

I

#

J

#

I

#

T

#

U

according to which the central bank moves interest rates with its perception of the natural rate of

interest

#

--

#

L

, and also responds to deviations of expected inflation

#

#$

from its potentially time-

varying target N

#

, deviations of expected output growth from its target

#

Q

#

QN

N

N

N

, and the output

gap

"

#

. In addition to allowing for time variation in the intercept, we allow for variation in the

target level of inflation, in the response coefficients to macroeconomic conditions, and in the degree

of interest-smoothing, which is an important element of the Fed’s reaction function (Coibion and

Gorodnichenko 2012b). Each time-varying coefficient is assumed to follow a random walk process

as in Boivin (2006). We estimate the coefficients of this reaction function as in Kozicki and Tinsley

(2009) and Coibion and Gorodnichenko (2011, CG henceforth) using data from 1969 to 2008 at the

FOMC meeting frequency using real-time forecasts of inflation, output growth and the output gap.

For robustness, we also consider an additional measure, the inflation target estimated by

Ireland (2006). Ireland uses an otherwise standard small-scale New Keynesian model with a Taylor

(1993) rule in which the target rate of inflation rate varies over time. He then estimates the

parameters of the model by maximum-likelihood methods using data on output, prices, and interest

rates from which he recovers the implied time path of the Fed’s target rate of inflation. Thus, whereas

our first measure of target inflation comes from single-equation of a Taylor rule with time-varying

coefficients on real-time Greenbook forecasts, Ireland’s approach is the polar opposite: estimation of

the entire structural model using final data for macroeconomic aggregates and no real-time forecasts.

Both approaches point toward rising inflation targets over the 1970s, peaking at

approximately 8% (Appendix Figure 10). The two measures also pick up rapid declines in target

inflation in the early 1980s, corresponding to the Volcker disinflation, and a prolonged subsequent

decline in the target inflation rate over the course of the 1990s and 2000s, with the target rate of

inflation reaching 2% in 2005 in both cases. At the same time, a number of qualitative differences are

present: Ireland’s measure points to a rapid increase in the inflation target starting around 1973,

reaching 8% in late 1974 before declining to 6% in 1975. In contrast, the CG measure points to only

a gradual increase in the inflation target during this time period. Second, while both measures reach

maximum values of 8% prior to the Volcker disinflation, the Ireland measure begins to decline in

1981 while the CG measure continues to rise until the end of 1982, at which point it drops much

more abruptly: 3% points over the course of just a few months.

To assess the effects of changes in target inflation rates on inequality, we estimate inequality

responses using equation (2) for either measure of shocks to the inflation target rather than RR

24

shocks. We present the results for cross-sectional standard deviations, for a 1% point decrease in the

inflation target in Figure 9 using the CG measure of target inflation. Using the Ireland (2006)

measure yields very similar results (Appendix Figure 11). First, a decrease in the Fed’s inflation

target leads to a rise in both earnings and income inequality: we can reject the null of zero response

for both at the 1% level. Second, both consumption and expenditure inequality also rise persistently.

Third, shocks to the inflation target generally account for a smaller fraction of the forecast error

variance than broader definitions of monetary policy shocks, as one might expect. They are