Quality of the local environment

London Borough of Hackney and the City of

London 2019

Authors: Alexander Miller, Poppy Middlemiss, Robert Tyler and Matthew

Carrington

Quality of the local environment | 2

● Content

London Borough of Hackney and the City of London 2019 1

Content 2

7.1 Introduction 4

7.1.1 Outdoor air quality 4

7.1.2 Indoor air quality 5

7.1.3 Climate change 5

7.1.4 Land contamination 5

7.1.5 Noise 6

7.2 Key facts about the quality of the local environment 7

7.3 Health and wellbeing impacts 8

7.3.1 Air quality - outdoor 8

7.3.2 Air quality - indoor 11

7.3.3 Climate change 12

7.3.4 Contaminated land 15

7.3.5 Noise 16

7.4 Number of people affected 17

7.4.1 Air quality - outdoor 17

7.4.2 Air quality - indoor 17

7.4.3 Climate change 18

7.4.4 Contaminated land 18

7.4.5 Noise 18

7.5 Inequalities 19

7.5.1 Age 19

7.5.2 Gender 20

7.5.3 Ethnicity 21

7.5.4 Disabilities and long-term conditions 21

7.5.5 Socio-economic deprivation 21

7.5.6 Location within Hackney and the City 22

7.6 Comparisons with other areas and over time 26

7.6.1 Air quality – outdoor 26

7.6.2 Air quality - indoor 30

7.6.3 Climate change 30

7.6.4 Contaminated land 34

7.6.5 Noise 34

7.7 Evidence and good practice 38

7.7.1 Air quality - outdoor 38

7.7.2 Air quality - indoor 46

7.7.3 Climate change 48

7.7.4 Contaminated land 51

7.7.5 Noise 53

Industrial noise 54

Transport noise 54

Quality of the local environment | 4

7.1 Introduction

This section describes several distinct, though interlinked, environmental factors

which influence health and wellbeing in Hackney and the City of London, namely:

● outdoor air quality

● indoor air quality

● climate change

● land contamination

● noise pollution

Though environmental damage has a negative impact on health, many actions taken

to improve population health can reduce impact on the environment. This includes

for example, policies designed to encourage active travel, and planning policies

which promote warmer homes and walkable communities.

In this respect, the potential relationship between population health and the

environment has been described as a virtuous circle. [1]

7.1.1 Outdoor air quality

Air pollution in the outdoor environment is a high profile public health concern –

though levels have been decreasing in recent decades, parts of inner-city areas such

as Hackney and the City of London remain above EU limit values and World Health

Organisation (WHO) guidelines. The extent of health problems associated with air

pollution is increasing as research in this area grows.

The main source of outdoor air pollution in the area is road transport – associated

pollutants include oxides of nitrogen, fine particles (PM10 and PM2.5), ozone,

sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide, benzene and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

[6].

For more information on transport and health, see the ‘Transport and travel’ section

of the JSNA.

Other key sources of air pollution locally include domestic gas, and commercial

cooking, as well as river transport in the City – see Figure 26 and Figure 27 for

example, and Table 3. Other sources of outdoor air pollutants include construction

work, as well as industrial and agricultural sources beyond the borough boundaries.

[2] Alongside manmade sources, there are also natural sources of air pollutants,

though these are much less significant.

Particulates and nitrogen dioxide are widely considered to be the two most important

pollutants – in terms of health impacts and concentration in the environment.

There are numerous other substances which are air pollutants – including ozone,

benzene, lead and other heavy metals, all of which have been found to be harmful to

health.

Quality of the local environment | 5

7.1.2 Indoor air quality

People may spend up to 90% of their day indoors, and as such, internal air pollution

can add significantly to the overall lifetime exposure to a range of harmful pollutants.

[3]

The indoor environment includes anywhere that people spend time – in particular,

the home, the workplace, and schools, though also hospitals, nurseries, shops,

inside vehicles, restaurants, bars, and hotels.

Indoor air pollution is particularly associated with cooking stove use in the home in

developing countries. [4] In the UK however, this is considered to be a much less

significant problem, though there are numerous other pollutants and sources. This

includes outdoor air pollution which impacts on indoor air quality. The most harmful

source of indoor pollution in the UK is tobacco smoke – this is discussed further in

the JSNA section on ‘Smoking’.

As well as being a more complex and less widely understood issue, with a less

developed evidence base, regulation of indoor air is more difficult outside of

commercial and industrial settings.

Several indoor air pollutants are associated with a range of illnesses. Some groups

of vulnerable people are likely to spend more time indoors, and so can be particularly

affected by indoor air quality.

7.1.3 Climate change

Over the last 50 years, human activities – particularly the burning of fossil fuels –

have released sufficient quantities of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases

(gases capable of absorbing infrared radiation) to trap additional heat in the lower

atmosphere, which has led to a rapid change in global climate. [5] This process was

described by the UK Chief Scientific Officer as “the biggest challenge that our

civilisation has ever had to face up to”. While some efforts to reduce climate change

require national and international cooperation, local actions can also be effective,

alongside building resilience to mitigate the effects of rising temperatures. Hackney

is among a majority of English local authorities who have declared a climate

emergency over the past year.

Climate change is likely to become a major environmental crisis, with effects already

evident locally. While much of the political effort to prevent it requires concerted

international action, individuals and organisations in Hackney and the City can lead

this effort. It is also important that local health and other services are aware of the

impacts and are prepared to adapt to the challenges – most particularly, in increased

summer heat waves and other extreme weather patterns.

7.1.4 Land contamination

Land contamination is a potential health risk in parts of the local area associated with

former industrial use. Industrial development from the late 18

th

century onwards saw

Quality of the local environment | 6

the growth of factories in Hackney. This, alongside the building over of farm land,

leaves a legacy of potential for ground contamination.

Materials of human origin underlie parts of the borough, and may be associated with

elevated levels of chemicals of concern - such as lead, polycyclic aromatic

hydrocarbons and asbestos.

Contaminated land can have serious consequences for both human health and the

environment.

7.1.5 Noise

Noise pollution can also be defined as “unwanted sound” and is a health concern in

many localities in Hackney and the City. Transport is the major source of the

problem though there are also issues caused by neighbours, construction sites and

entertainment venues for example.

Noise can have long and short-term impacts on health, which are often

underestimated. These include cognitive impairment, sleep disturbance, tinnitus,

annoyance, negative impact of children’s learning, and a small increase in the risk of

cardiovascular disease. [6] [7]

There are a number of groups who are particularly vulnerable to the impact of noise,

including children, older people and those in poor health. Certain occupation types

are also more vulnerable.

National research reports that noise problems are particularly associated with high

density housing, rented accommodation (both social and private sectors), socio-

economic deprivation, and urban environments. [8]

Box 1: Definitions

Attributable deaths – an estimate of the proportion of deaths caused by a risk factor in a

population. For example, by consulting experts, and looking at rates of death in

populations more and less exposed to man-made fine particulate air pollution, it is

thought that 5% of all deaths of people aged over 30 in England can be attributed to

this risk factor.

CO (carbon monoxide) – a gas produced when carbon-based fuel burns incompletely.

Outdoor concentrations of CO are generally low in the UK, though it can be found in

toxic concentrations indoors.

CO

2

(carbon dioxide) – the main “greenhouse gas” which contributes to man-made climate

change.

COMEAP – the Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollution, a panel of experts who

advise the UK Government.

Quality of the local environment | 7

Contaminated land - a specific legal definition whereby the land must cause significant

harm, or present significant possibility of such harm. In London, this is normally

associated with former industrial sites.

Decibels (abbreviated to dB) - a measure of the volume of sound. Safe and healthy levels

are defined with reference to the World Health Organisation guidelines. dB(A) refers

to a measure that is adjusted to reflect the ear's response to different frequencies of

sound.

Heatwave – the UK Met Office uses the World Meteorological Organisation definition of a

heatwave, which is "when the daily maximum temperature of more than five

consecutive days exceeds the average maximum temperature by 5°C” (with the

comparison being the period 1961-1990).

LEN (Low Emission Neighbourhood) – An area-based scheme that includes a package of

measures focused on reducing emissions (and promoting sustainable living more

generally).

MSOA (Middle Super Output Area) – geographical areas defined during the UK Census to

support data release and analysis. Each has an average of 7,200 residents. There

are 28 MSOAs in Hackney and one in the City of London.

NOx (oxides of nitrogen). A group of polluting compounds, including Nitric Oxide (NO) and

Nitrogen Dioxide (NO

2

) that have been associated with a number of short and long-

term health conditions including respiratory and cardiovascular conditions.

PM2.5 and PM10 (particulate matter 2.5 and 10). Air pollutants are made up of a complex

mixture of non-gaseous particles of varied physical and chemical composition. Small

particles are defined by their diameter - here, below 2.5 micrometres in diameter

(PM2.5) or below 10 micrometres in diameter (PM10).

ULEZ – Ultra Low Emission Zone – An area within which motor vehicles need to meet

exhaust emission standards or pay a daily charge to travel.

Urban heat island – higher temperatures experienced by urban areas (such as inner London)

due to materials like tarmac and stone absorbing and storing more heat than

vegetated areas, along with concentrated energy use due to the larger population.

ZEN (Zero Emissions Network) – business engagement network to encourage businesses to

reduce emissions.

7.2 Key facts about the quality of the local environment

● There are several distinct, though interlinked, environmental factors which

influence health and wellbeing in Hackney and the City as elsewhere. People

living in the most socio-economically deprived circumstances, who are at

increased risk of a range of health problems, are often the most vulnerable to

these influences.

Quality of the local environment | 8

● Outdoor air pollution, mostly from transport sources in Hackney, and industrial

sources in the City, is thought to be among the largest causes of ill-health and

premature death, and its reduction is a significant priority in both local

authority areas.

● The overall impact of poor indoor air quality is lower. In the home, it stems

from a wide range of pollutants and sources, some of which are not well

understood. There are also exposures associated with various occupations,

some of which have a major effect on health - for example in workers in

factories, and the beauty industry.

● Climate change is a major global threat, though in the short term less so in

wealthy countries with a temperate climate such as the UK. Residents of

Hackney and the City of London are thought to be particularly vulnerable to

heatwaves (due to the urban heat island effect). These are becoming

increasingly common as global temperatures continue to rise.

● In Hackney, most carbon emissions can be ascribed to domestic sources, with

a similar volume coming from industrial and commercial sources, and less

from transport. In the City of London, almost all carbon emissions come from

the industrial and commercial sectors. Local residents also have an impact on

carbon emissions produced elsewhere – for example, through products they

use.

● Due to its inner-city location, and high level of socio-economic deprivation,

Hackney has recently been ranked among the three areas in England most

vulnerable to heatwaves. [9]

● Hackney and the City of London are exposed to the risk of flooding, with

significant areas within the floodplain of the River Thames and its tributary, the

River Lea. This risk is likely to grow as the impact of climate change grows.

● Data show that, due to a relatively energy efficient housing stock, and a less

carbon intensive local economy, Hackney has a relatively low level of per

person CO

2

emissions than the national average. [10]

● Contaminated land is an ongoing problem in Hackney, and may be impacting

on population health in some local areas. Local estimates suggest that almost

25% of Hackney is associated with current or past potentially contaminating

land use, but only a small proportion of these areas are likely to be resulting in

harm to local people.

● Noise can have serious implications for health, and is particularly acute in

inner-city boroughs such as Hackney and the City. Transport is the major

source of the problem though there are also issues caused by neighbours,

construction sites and entertainment venues for example

7.3 Health and wellbeing impacts

7.3.1 Air quality - outdoor

Outdoor air pollution is a major contributor to ill health and early death in Hackney

and the City of London. Estimates suggest that the proportion of deaths attributable

to pollution locally is among the highest in the country. Current air pollution levels

locally exceed legal standards, and have a negative impact on the health of all

residents and visitors. However, those with existing conditions and/or living in socio-

economically deprived circumstances are particularly affected, making air pollution a

contributor to health inequality.

Quality of the local environment | 9

As well as chronic long-term effects, poor outdoor air quality causes acute health

problems for people with respiratory conditions.

Specific harmful health effects include suppressed lung growth in children, asthma

and other chronic lung conditions, onset of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease,

cancer, and neurodegenerative disease (dementia). [11] Pregnant women exposed

to air pollution are at increased risk of restricted foetal brain growth, as well as

having low birth weight babies, stillbirth and infant mortality. [11] [12] Air pollution

can affect lung function, exacerbate asthma and increase cardiovascular and

respiratory disease. [13] Research continues to uncover previously unknown

harmful effects of air pollution. [11]

Measures of overall population impact are largely based on expert elicitation and

modelled estimates. For example:

● in 2015 the Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollution (COMEAP)

estimated that there were 29,000 attributable deaths in the UK annually due to

PM2.5 pollution alone [14] [15]

● a study by the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

(Defra), estimated that a further 23,500 people die each year in the UK due to

NO2 (nitrogen dioxide) [16]

● in 2010, an estimated 9,416 deaths in Londoners were attributable to long-

term exposure to NO2 and PM2.5 overall [17]

There is considerable uncertainty around these estimates, however. Recent

research suggests that the number of deaths attributable to air pollution may be

twice as high as these estimates across Europe, causing a 2.2 year reduction in

overall life expectancy. [18] In 2018, COMEAP revised their estimate to between

28,000 and 36,000 deaths nationally from all sources of human made air pollution.

[19]

Illnesses and causes of death most commonly associated with air pollution include

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and lower respiratory tract infections,

cardiovascular disease (CVD) (including coronary heart disease and stroke),

diabetes, and cancers of the respiratory system. For more information on these

conditions, see the ‘Adult health and illness’ chapter of the JSNA.

Figure 1 shows the proportion of deaths from each of these conditions that can be

attributed to particulate air pollution locally.

Figure 1: Estimated annual attribution of outdoor particulate air pollution to deaths in

Hackney and the City of London (all ages, 2017)

Quality of the local environment | 10

Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation [4]

International pollution, which drifts into London during particular weather events, can

also impact health – this is particularly the case with springtime pollution episodes,

which can build up across the continent over several days. However, it is overall

background levels of pollution which are the major contributor to ill-health, rather

than these specific episodes.

There is growing evidence of the effects of air pollution, including NOx, on cognitive

performance. For example, recent research has demonstrated a relationship with

road traffic accidents, and it is likely that there will be a negative impact on other

activities requiring high mental effort and concentration. [20] There is evidence of an

increasing correlation between air pollution levels and reduced cognitive

performance with age, particularly in less educated males. [21]

Beyond the direct impact on health and wellbeing, environmental factors (in

particular air pollution) have a significant, but difficult to quantify, economic impact –

this includes the cost of additional GP visits and working days lost to illness.

Estimates of the health and care costs show these to be significant in Hackney and

the City (Table 1).

Table 1: Estimated costs to local health and care services of PM2.5 and NO

2

pollution in £ millions (2019; age 18+ only)

Hackney

City of London

PM2.5

NO

2

PM2.5

NO

2

Primary care

£4.6m

£3.8m

£0.2m

£0.2m

16

(24% of total)

8

(15% of total)

15

(11% of total)

4

(7% of total)

8

(10% of total)

3

(21% of total)

Quality of the local environment | 11

Secondary care

£12.0m

£5.5m

£0.6m

£0.2m

Medication

£8.6m

£5.1m

£0.4m

£0.2m

Social care

£5.1m

£5.3m

£0.3m

£0.2m

Combined costs

£30.3m

£19.9m

£1.6m

£0.8m

Source: Public Health England [22] and GLA SHLAA 2016-based population estimates

Note that figures may not add up due to rounding

Air pollution also has a wider economic impact than this. The United Nations

estimates that developed countries lose 2% of GDP to urban air pollution. [23] This

proportion is likely to be considerably higher in central London.

Concerns around the health impacts of air pollution can also negatively affect

people’s enjoyment and use of the wider local environment, which may limit

opportunities for physical activity including active travel. It has been demonstrated

that the health impact of air pollution is worse for commuters using motorised

transport than those travelling by bicycle or on foot. This is due to high levels of

pollutant exposure inside vehicles, as well as harms caused by a lack of physical

activity. [24]

Air pollution contributes to land contamination across wide areas in the longer term.

This effect has been observed in parks such as Hampstead Heath which have higher

levels of lead than similar areas outside London. [25]

As well as impacting local air pollution, burning hydrocarbons is a major source of

carbon dioxide gas – the major cause of climate change.

Actions taken to reduce outdoor air pollution are likely to drive a further range of

public health co-benefits – reduced dependency on fossil fuel based transport

sources in particular can reduce obesity, physical inactivity, and social isolation.

7.3.2 Air quality - indoor

Indoor air pollution is a major cause of ill health and mortality globally, associated

with solid fuel cooking fires in developing countries. In wealthier countries, such as

the UK, a range of other indoor pollutant chemicals are in regular use, although

these are considered to be of a much lower health impact overall. [26]

People in specific occupations may be of increased risk of exposure to indoor air

pollution – including drivers, industrial workers who may be exposed to mineral

dusts, and people who work in beauty salons. [27] [28]

The government’s Clean Air Strategy [3] has recognised the importance of indoor air

pollution: “The principal forms of indoor air pollution are particulate matter (PM) and

Non-Methane Volatile Organic Compounds (NMVOCs). PM is produced by many

forms of cooking and home heating, most notably from combustion in open fires and

Quality of the local environment | 12

stoves. NMVOCs are emitted by a wide variety of chemicals that are found in

carpets, upholstery, paint, cleaning, fragrance, and personal care products. Sulphur

dioxide (SO2) is emitted by coal burned in open fires”.

There is a growing body of evidence showing that people inside vehicles are

exposed to relatively high levels of pollution. [24] Evidence is also emerging about

high concentrations of particulates in parts of the London Underground system. [29]

The health impacts of some specific sources of indoor air pollution are described

below.

● Carbon Monoxide. Nationally, there are around 40 deaths recorded each

year due to CO poisoning, 4,000 A&E attendances, and 200 hospital

admissions. [30] It is believed that the longer term chronic effects of non-

acute exposure are likely to be a more significant health risk.

● Fine particulate matter. Deaths and ill-health associated with particulate

matter indoors are included in the overall estimates reported in section 7.3.1.

● Dust mites and other allergens. Pets, dust mites and damp and mould in

homes can all cause allergic conditions, and can exacerbate respiratory

problems. [31]

● Oxides of nitrogen. Deaths and ill-health associated with oxides of nitrogen

indoors are included in the overall estimates reported in section 7.3.1..

● Lead dust and mineral fibres. Asbestos, a mineral fibre, can cause lung

disease, and is mostly associated with historical industrial exposure. Lead

dust exposure is particularly associated with old paint disturbed during

renovations – it can accumulate in the body and cause significant health

problems, particularly in children.

● Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. The overall health impact of these

substances is unclear, though they are likely to be associated with a small

number of cancers.

● Radon. Thought to be responsible for around 1,100 lung cancer deaths each

year in the UK in affected localities.

● Tobacco. Second hand smoke indoors is a serious public health risk. For

further information see the JSNA section on ‘Smoking’.

● Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). These can cause short-term

respiratory irritation or headaches, and exacerbate respiratory problems.

Long-term effects may include increased risk of some cancers. [32] [33]

While considered separately here, it should also be noted that outdoor air pollution is

also a major source of indoor air pollution. For example, research suggests that

75% of the daily variation in particulate matter in indoor air can be explained by

changes in outdoor air, although this Indoor/Outdoor (I/O) ratio can vary greatly,

even within the same building. [8] [10]

7.3.3 Climate change

Globally, a range of major health and societal impacts of climate change are

predicted, as described in Table 2. In temperate, developed countries (such as the

UK) the effects are likely to be more limited, though still significant.

Quality of the local environment | 13

The major health impact in Hackney and the City will be an increase in deaths and

ill-health during hot weather in the summer. Certain population groups, including the

very old and young, and people with long-term conditions are particularly vulnerable

to the effects of high temperatures. Winters are expected to become increasingly

warmer and wetter, with higher risk of flooding. [34] A worsening of respiratory

conditions in the UK can be expected due to a combination of hot weather and poor

air events. This impact of climate change is worsened by the ‘Urban Heat Island’

effect – this happens because materials like tarmac and stone absorb and store heat

more than vegetated areas, along with concentrated energy use due to the larger

population – see Figure 2.

Figure 2: The average temperature across the 2006 summer in London

demonstrating the Urban Heat Island effect – Hackney and the City boundaries are

shown in green.

Source: [35]

Extreme weather patterns are becoming more likely due to rising temperatures, with

rainfall concentrated in storm events. Major floods which affected parts of the UK

during 2007, 2013 and 2019 show the potential impact of this, as do the heatwaves

in 2003, 2006, 2013, 2018 and 2019. The heatwave in 2003 led to 2,000 deaths

nationally, while estimates suggest that the heatwaves in 2018 and 2019 may each

have been responsible for around 1,000 deaths nationally [36] [37] Older people,

people with existing medical conditions, and outdoor workers would be particularly

affected.

Quality of the local environment | 14

Climate change is likely to make winters in England milder, as well as wetter. This is

likely to reduce the numbers of excess winter deaths, though this would not offset

the additional summer deaths. For more information on excess winter deaths locally,

see the JSNA section on ‘Vulnerable Adults – Older People’.

As it historically developed around a port, like many cities in Europe, London is

vulnerable to sea level rise and associated flooding. The increased likelihood of

drought is another probable consequence of climate change. [9]

Some increase in the prevalence of food and vector borne infectious disease may

also be expected in the UK. [38] For more information on the impact of infectious

disease locally, see the JSNA section on ‘Infectious Disease’.

Wider effects of climate change will also impact on public health - this includes the

loss of biodiversity. Diverse and well-functioning ecosystems provide clean air, fresh

water and food security, as well as contributing in turn to a stable climate. [39]

Beyond this, it is likely that the global effects of climate change will increase the risk

of political instability and war internationally – the impact of this locally is difficult to

predict, though increased migration from worse affected countries, and reduced

economic growth, could be expected, with consequent health impacts. In 2019,

international experts polled by the World Economic Forum, suggested that issues

related to climate change are the biggest risk to the world currently. [40] Less

predictable effects are likely to have implications for the UK, although the specific

health impacts are uncertain.

It is these larger risks that led Hackney council, along with the majority of other local

authorities nationally, to recognise in 2019 that the world is facing a “climate

emergency”. This declaration acknowledges the limited time available to make

changes which could prevent these worst case scenarios.

Carbon based fuels are the major contributor to air pollution. High temperatures can

also increase the production of air pollutants such as ozone, as well as extending the

season of allergenic pollen.

Many local efforts to reduce climate change have the same health co-benefits as

efforts made to reduce air pollution more widely.

Table 2: Summary of the impacts of climate change on human health

Consequence

of climate

change

Impacts on human health

Increased

temperatures

and extended

heat waves

Increased risk of heat-related deaths during heatwaves, particularly

among vulnerable groups. Higher levels of ultraviolet radiation

which is a major cause of skin cancer. Decreased cold-related

mortality in temperate countries.

Quality of the local environment | 15

Flooding

Immediate risk of drowning. Increased risk of water-borne

infections. Food shortages and famine associated with loss of crops

and livestock. Increased risk of land contamination. Physical

damage to healthcare settings. Impact on mental health.

Drought

Risk of food shortages and famine associated with loss of crops

and livestock. Significant displacement of populations.

Wildfires

Increased risk of fire-related death or harm. Impact of poorer air

quality on health. Impact on mental health.

Vector-borne

disease

Increased geographical spread and reproductive speed of

infectious diseases spread by food and water, and those

transmitted by insect vectors

Air pollution

and

aeroallergen

levels

Climate change is expected to have a negative impact on outdoor

air pollutants, in particular ozone. Warmer winters are likely to

extend the season for people suffering from hayfever in temperate

countries.

Natural

disasters and

extreme

weather

events

Increased risk of injury or loss of life due to hurricanes, tsunamis

etc. Destruction of health infrastructure.

Source: Adapted from [34]

Climate change will have serious consequences for human health in the coming

decades. Though the UK, as a wealthy country with a temperate climate, will be less

seriously affected than most parts of the globe, it is important for local services to be

aware of these changes.

7.3.4 Contaminated land

’Contaminated Land’ has a specific legal definition under Part 2A of the

Environmental Protection Act 1990. In order to determine areas as contaminated

land, the land must cause significant harm or present significant possibility of such

harm to any receptor. This includes the potential to cause significant pollution of

surface waters (such as lakes or rivers) or groundwater. However, it should be noted

that land that does not fit the legal definition under Part 2A may still be affected by

contamination. Contamination can occur through the deliberate or accidental release

of chemicals, or as a result of historical industrial practices. Land is still becoming

contaminated through the release of chemicals and other human activities.

Soil lead concentrations for example are generally high across London with some

local variation. [25] Levels are highest in central London, and there are differences

associated with land use. Levels in public parks tend to be lower than in domestic

gardens – levels are generally higher in older dwellings (probably associated with

ash from burned domestic waste and the use of lead-based paints), and higher still

in industrial areas. [41]

Quality of the local environment | 16

Contaminated land can have serious consequences for both human health and the

environment. Increased risk of flooding is likely to be a consequence of climate

change, and may also facilitate the mobilisation of soil contaminants such as arsenic.

[42]

Health consequences from exposure to land contamination are thought to vary

greatly depending the type and quantity of the contaminant(s), level, mode and

duration of exposure, and individual vulnerability. [43]

Compounds associated with land contamination have been linked to a range of

health impacts including skin and eye irritation, fatigue and nausea, cancers,

congenital disorders, kidney damage and other long-term conditions. However, the

evidence of these health impacts tends to be inconsistent and of variable quality, and

associations linked to long-term exposure are very difficult to demonstrate. [44]

The health impacts of exposure to specific land contaminants, such as landfills, are

particularly difficult to define as many chemicals with different known adverse effects

usually coexist (Figure 3). Beyond direct exposure, there is further potential

contamination of water bodies and supplies.. In addition, contamination of many sites

is poorly documented and no information is available when contamination results

from illegal practices.

Evidence does exist around the impact of stress and anxiety related to living near

hazardous waste sites, which may be more broadly applicable to living near or on

contaminated land generally. [44]

Figure 3: Routes of potential human exposure to land contaminants

Source: Adapted from Environment Agency [45]

7.3.5 Noise

The most common negative effect of noise is annoyance, but there are a number of

other effects, including: sleep disturbance; hearing impairment; heightened cortisol in

Quality of the local environment | 17

the blood (a marker of stress); impairment of cognitive performance in children; and

increased risk of developing CVD in those exposed long-term to noise pollution. [46]

A large study in 2015 found that across London there are significant excess deaths

associated with traffic noise, however it’s not clear that this is causal. [47]

WHO estimate that one million healthy years of life are lost every year in Western

Europe because of traffic noise, particularly due to the contribution of raised cortisol

levels to CVD. [48]

Impairment of early childhood development and education caused by noise may

have lifelong effects on academic achievement and future health. [49]

High levels of traffic noise are also associated with higher levels of air pollution,

which can make it difficult to attribute specific underlying causes of related health

impacts. Some recent research suggests that air pollution, rather than noise

pollution, is associated with higher levels of low birth weight babies. [12]

7.4 Number of people affected

7.4.1 Air quality - outdoor

All residents and visitors to Hackney and the City of London are affected by the high

levels of outdoor air pollution to some extent, although it affects vulnerable

population groups, such as older people with long term health conditions, the most.

Concentration of particulate pollution in Hackney and the City is high compared to

other parts of England and London. In 2017, the adjusted annual concentration of

fine particulate matter in Hackney was 12.2 µg/m

3

and in the City of London it was

12.6 µg/m

3

. [50]

Estimates for Hackney suggest that as many as 7.0% of all deaths in those aged 30+

may be attributed to particulate air pollution, and 7.1% in the City of London. [50] In

London as a whole, 6.6% of deaths in this age range can be attributed to particular

pollution, compared to a national average of 5.2%. Additional local deaths

associated with NO

2

in particular are difficult to estimate.

According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study, an estimated 54 deaths in

residents of Hackney and the City were attributable to air pollution in 2017. [4]

7.4.2 Air quality - indoor

All residents and visitors to Hackney and the City are affected to some extent by

indoor pollutants.

According to the Global Burden of Disease Survey, five deaths in residents of

Hackney and the City were attributable to occupational exposures to particulate

matter, gases, fumes and diesel exhausts in 2017. [4] Three deaths in this same

year were estimated to be attributable to residential radon gas.

Quality of the local environment | 18

7.4.3 Climate change

In Hackney, most carbon emissions can be ascribed to domestic sources, with a

similar volume coming from industrial and commercial sources, and less from

transport. The National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory does not identify any

individual large industrial installations in the borough. [51]

In the City, almost all carbon emissions come from the industrial and commercial

sector. Per person CO

2

emissions are particularly high in the City due to the small

resident population. The National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory identifies four

individual large industrial installations in the borough. [51]

Climate Just, a network of organisations including the Environment Agency and the

Joseph Rowntree Foundation, have produced a model estimating the vulnerability of

small areas (MSOAs, see Box 1) across England to flood and heat hazards

associated with climate change. This is based on population vulnerability, ability to

respond, ability to recover and likelihood of the hazard occurring. The model

suggests that two out of 28 (7%) MSOAs in Hackney have a high vulnerability to

flooding, and 13 out of 28 (46%) MSOAs have a high vulnerability to heat. The one

MSOA in the City of London is categorised as having a high vulnerability to flooding

and heat. [52]

Across London, a total of 468 deaths have been estimated to have resulted from the

summer heatwaves of 2018, the highest rate of death in England. [53] Estimates are

not available for Hackney and the City specifically.

7.4.4 Contaminated land

The location of contaminated and potentially contaminated land in Hackney has

been identified under Part 2A of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 (see section

7.5.6). In total, 0.35 hectares of contaminated land have been identified locally, with

a further 434.6 hectares identified as potentially contaminated (23% of the land in the

borough).

No contaminated land sites in the City of London have been identified.

7.4.5 Noise

Noise from transport, construction sites and entertainment venues are particular

issues in inner London.

Hackney Council received 5,413 complaints about noise in 2015/16. The Public

Health Outcomes Framework estimates that 15% of the local population are exposed

to transport noise of 65dB(A) or more in the daytime, and 18% at night. [54] The

majority of complaints received by the council concern music.

The Hackney Matters Antisocial Behaviour (ASB) e-panel Survey in 2015 found that

over 90% of those surveyed had experienced noise from people in the street at

night, 85% from sirens, 80% from noise from neighbours at night and nearly 70%

from noise from neighbours during the day. For more information, see the

‘Community Safety’ section of the JSNA.

Quality of the local environment | 19

The City of London received 1,093 complaints about noise in 2014/15 from residents

and businesses. These concerned a range of sources, but were predominantly

related to demolition/construction sites, street works and entertainment venues.

The Public Health Outcomes Framework estimates that 28% of the resident

population are exposed to transport noise of 65dB(A) or more in the daytime, and a

similar proportion at night.

7.5 Inequalities

As well as affecting a significant number of individuals in total, environmental

influences are a source of health inequalities.

7.5.1 Age

Air pollution disproportionately affects the elderly and children, as well as those with

heart and respiratory disease. Estimates from the GBD study suggest that most

related deaths in residents of Hackney and the City occur in people aged 80 or older

(Figure 4).

Other research has shown that concentrations of particulate matter in a sample of

classrooms in London are above guideline values. [55]

Older people are particularly vulnerable to heatwaves associated with climate

change. For example, of the 468 deaths in London estimated to have resulted from

the summer heatwaves of 2018, 92% were thought to have occurred in people aged

65 or older. [53]

Chronically ill and elderly people are also more sensitive to noise disturbance. [56]

As children require more sleep than adults, they are more likely to be disturbed by

night-time noise pollution. Impairment of early childhood development and education

caused by noise may have lifelong effects on academic achievement and health.

[49] Older adults, and people in poor health, are also considered to be more

vulnerable to the effects of noise.

Figure 4: Estimated annual attribution of air pollution to deaths in Hackney and the

City of London by age (all ages, 2017) [4]

Quality of the local environment | 20

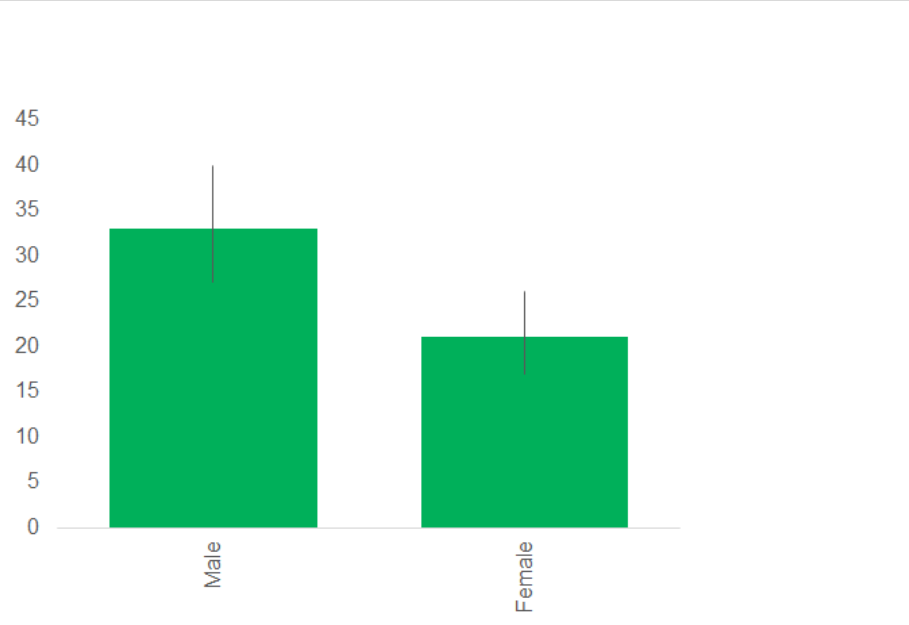

7.5.2 Gender

Estimates from the GBD study suggest that males are more likely to suffer

premature mortality due to the effects of air pollution than females (Figure 5).

There is no clear local evidence for particular inequalities with respect to gender and

other environmental health determinants.

Quality of the local environment | 21

Figure 5: Estimated annual attribution of air pollution to deaths in Hackney and the

City of London by gender (all ages, 2017) [4]

7.5.3 Ethnicity

Nationally, the higher proportion of Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) people

living in inner-city areas means that there are major inequalities in exposure to

outdoor air pollution, urban noise pollution and heat waves – all of which are more

common in built up areas. [57]

7.5.4 Disabilities and long-term conditions

Air pollution, heat waves, and noise pollution disproportionately affect people with

existing medical conditions, including heart and respiratory disease.

7.5.5 Socio-economic deprivation

Though the relationship is complex, overall air and noise pollution are

disproportionately experienced by people in lower socio-economic groups, who tend

to be more concentrated in inner-city areas where roads are more congested. [57]

[58] Other sections of the JSNA also show that more deprived residents also have

higher rates of cardiovascular and respiratory disease, which increase the impact of

pollution.

Research published in 2017 confirmed that many schools in deprived parts of East

London were exposed to particularly high levels of air pollution. [59]

Poor indoor air quality (with high levels of VOCs, particulates and NO

2)

are

associated with poor housing standards, linked to socio-economic deprivation. [11]

Dampness is more common in homes that have insufficient heating, ventilation and

insulation, and in homes that are overcrowded – again, more common among low

Quality of the local environment | 22

income households. People working in manual and lower skilled occupations (such

as drivers, industrial workers, or those working in nail salons) are also at increased

risk of exposure to indoor air pollution (see section 7.3.2).

While the causes of climate change are driven disproportionately by the actions of

wealthier individuals, the health impacts are more commonly experienced by those

living in deprived circumstances. It is estimated that the wealthiest 10% of the UK

population produce more lifestyle CO

2

emissions than the poorest 40%. [60] [61]

Exposure to noise pollution is more common among socio-economically deprived

groups, linked to higher housing costs in quieter areas plus the costs of insulation.

[8] Occupational exposures to noise pollution are also linked to socio-economic

status. Shift workers are also thought to be particularly vulnerable to noise-related

harms due to sleeping at noisier times of the day. [8]

In general terms, people living in more deprived circumstances are less likely to be

able to move houses or jobs to avoid any environmental nuisance or harm.

7.5.6 Location within Hackney and the City

Inner-city areas with high traffic density are particularly affected by air pollution.

These areas are also more vulnerable to the health impacts of climate change due to

the urban heat island effect. [35]

Locally, the areas with the highest rates of pollution are Hackney Central,

Shoreditch, the area close to the A12 in Hackney Wick, and the whole of the City of

London (Figure 6). The highest concentrations of pollutants in both Hackney and the

City are around major roads.

Estimates of the number of deaths attributable to PM2.5, however, suggest that

these are evenly spread across Hackney. [62] This highlights the difficulty in clearly

ascribing the impacts of air pollution geographically, as people will be exposed

where they live, work and study; and longer-term impacts will be affected by areas

they have spent time in over the course of their life.

There is also significant variation in air pollution exposure over very small areas.

Shelter from air movements caused by tall buildings in parts of London, for example,

can create a ‘street canyon’ microclimate, thus concentrating pollution over time.

[63]

Quality of the local environment | 23

Figure 6: Average annual concentrations of nitrogen dioxide (NO

2

) across Hackney

and the City of London (2016)

Source: [64]

Quality of the local environment | 24

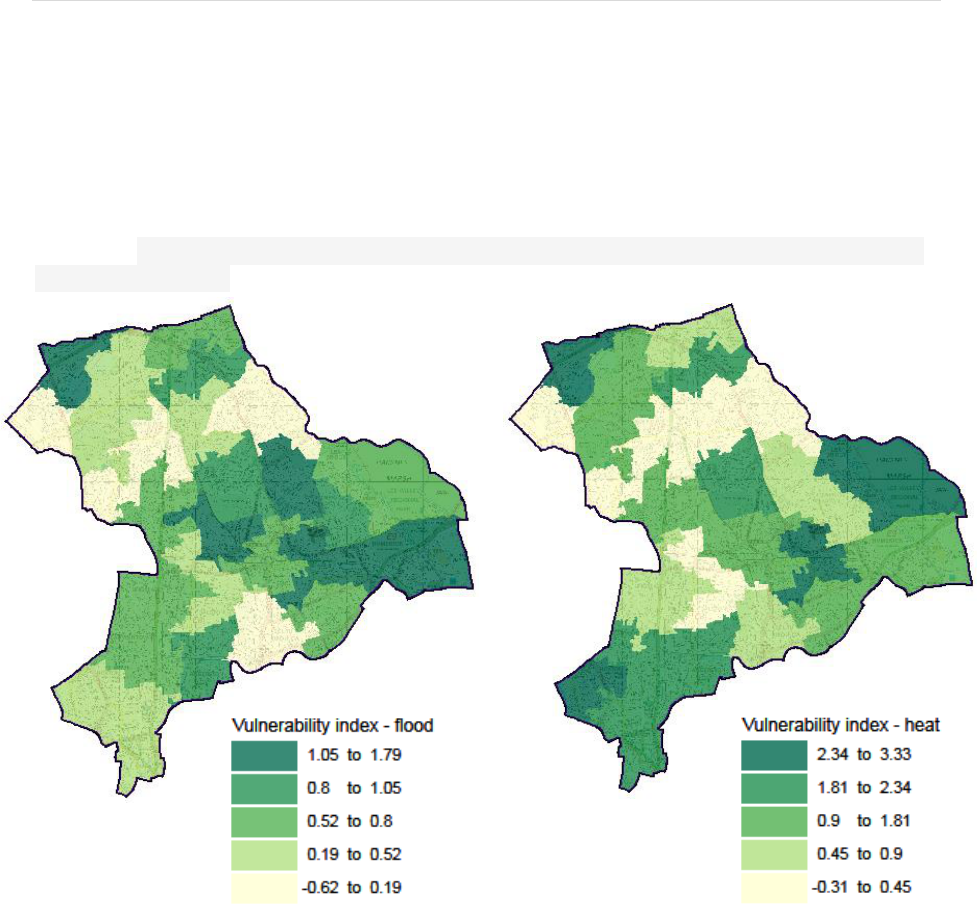

Based on the estimates of risk produced by Climate Just, vulnerability to flood and

heat in Hackney, (based on population vulnerability, ability to respond, ability to

recover and likelihood of the hazard occurring) is concentrated in different parts of

the borough – see Figure 7.

Figure 7: The socio-spatial vulnerability index to heat and flood from climate change

in Hackney (2014)

Source: Climate Just [52]

The location of contaminated and potentially contaminated land in Hackney is shown

in Figure 8.

Quality of the local environment | 25

Figure 8: Contaminated and potentially contaminated land in Hackney (2016)

Source: London Borough of Hackney

Figure 9 shows the estimated average levels of traffic noise experienced locally in

Hackney and the City of London. This follows a broadly similar geographical pattern

in Hackney as that shown in Figure 6 for air pollution, though less so in the City

where sources are not primarily road transport.

Quality of the local environment | 26

Figure 9: 24 hour annual average traffic noise level in decibels with weightings

applied for the evening and night periods (2012)

Source: www.extrium.co.uk

7.6 Comparisons with other areas and over time

7.6.1 Air quality – outdoor

The Public Health Act was passed in 1891, creating the first financial pressure on

businesses in London to reduce smoke emissions which were responsible for many

thousands of deaths at the time. Pollution levels in London were comparable in the

Victorian era to those experienced by cities such as Delhi and Beijing currently. The

Quality of the local environment | 27

Clean Air Act was passed in 1956 in response to continuing smogs in the UK,

coinciding with the peak of negative consequences of industrialisation in the UK.

Pollution is much less visible now, over 60 years after this law was passed, which

has led some to suggest that there has been some complacency over the issue in

recent years. [5]

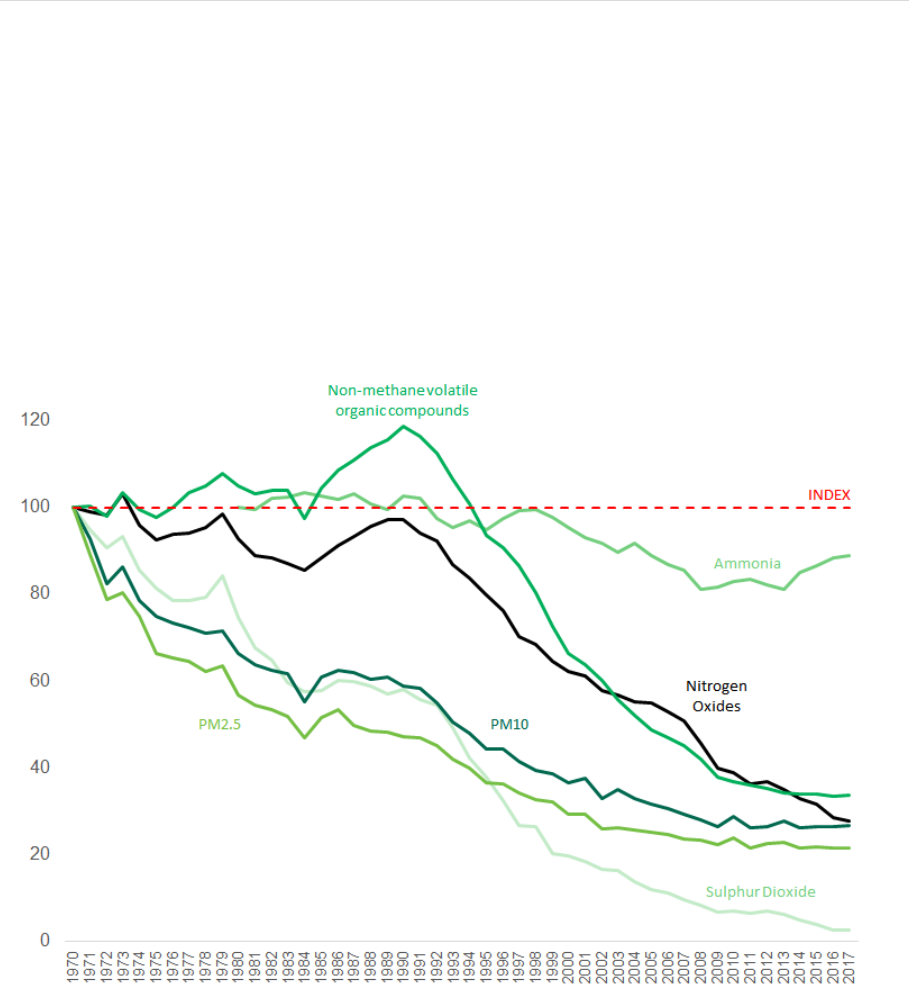

While overall levels of emissions in the UK have fallen significantly in recent

decades, the resulting decline in concentrations have been slower in London and

levels overall remain well above legal limits (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Trends in emissions of major air pollutants in the UK (1970 - 2017)

Note: Comparator index line shows the level of emissions if they had remained constant from the

beginning of the time trend

Source: Defra

Locally, concentration of fine particulate pollution is higher than regional and national

averages (Figure 11). However, there is evidence of a reduction in the annual levels

of PM2.5 since 2010 in City and Hackney (Figure 12).

Quality of the local environment | 28

Figure 11: Annual concentration of man-made fine particulate matter (PM2.5)

adjusted for population exposure (µg/m

3

, 2017)

Source: Defra. Confidence intervals not provided. [50]

Figure 12: Annual concentration of man-made fine particulate matter (PM2.5)

adjusted for population exposure (µg/m

3

, 2010-17)

Source: Defra. Confidence intervals not provided. [50]

Figure 13 shows that the fraction of all-cause adult mortality attributable to

particulate air pollution in Hackney and the City is among the highest of Hackney’s

statistical peers. However, there has been a downward trend in recent years, and at

a faster rate than national and regional trends (Figure 14), which mirrors the decline

in pollutant levels. Care should be taken when interpreting these trends and

comparisons, as confidence intervals are not available in the published data to

determine if they are statistically significant..

Quality of the local environment | 29

Figure 13: Fraction of all-cause adult mortality attributable to anthropogenic

particulate air pollution, measured as fine particulate matter, PM2.5 (age 30+, 2018)

Source: Public Health Outcomes Framework. Confidence intervals not provided. [50]

Figure 14: Percentage of all-cause adult mortality attributable to anthropogenic

particulate air pollution measured as fine particulate matter, PM2.5 (age 30+, 2010-

2018)

Source: Public Health Outcomes Framework. Note: Confidence intervals not provided. [50]

The concentration of diesel vehicles in England, and more widely in Europe, is

unique globally. The use of small diesel delivery vehicles nationally is likely to have

increased over time, with an increase in internet shopping and home deliveries.

However, recent national efforts to regulate diesel vehicles will have helped to

mitigate against some of the negative impacts of diesel vehicles of this at least to

some extent.

Quality of the local environment | 30

Predictions suggest that air pollution will continue to fall in Hackney and the City over

time, particularly from transport sources. As a result, the proportionate contribution

from domestic and commercial sources will correspondingly increase. [2]

7.6.2 Air quality - indoor

No data are available to compare the quality or impact of indoor air quality in

Hackney and the City with other areas.

High concentrations of outdoor air pollutants will have a significant impact on indoor

air and so the data reported in 7.6.1 have some relevance here.

Due to the downward trend in smoking prevalence locally (and nationally), indoor air

pollution from tobacco smoke will have declined similarly in recent years – for more

information, see the JSNA section on ‘Smoking’ in the ‘Lifestyle and behaviour’

chapter.

7.6.3 Climate change

Carbon dioxide is the main greenhouse gas.

Figure 15 shows that the level of CO2 emissions per person in Hackney are lower

than the national and regional average, and most similar areas in London. This may

partially reflect the relative efficiency of using transport and other infrastructure in

cities.

In Hackney, the overall level of carbon emissions fell by 19% between 2005 and

2015, from 915,000 to 742,000 tonnes of CO2. Per person CO2 emissions also fell

during this period, from 4.2 to 2.8 tonnes (Figure 16). In the City of London, the

overall level of carbon emissions fell by 48% over this same period, from 1,641,000

to 860,000 tonnes of CO2. Per person estimates for the City of London are not

presented, as the figures are artificially inflated due to exclusion of the large number

of daytime City workers/commuters from the denominator.

Quality of the local environment | 31

Figure 15: Estimated CO

2

emissions (tonnes per person, 2015)

Source: DECC. Confidence intervals not provided. [50]. NB Figures for the City of London are not

shown as they do not take into account the daytime worker population.

Figure 16: Estimated CO

2

emissions (tonnes per person, 2005-2015)

Source: DECC. Confidence intervals not provided. [50]. NB Figures for the City of London are not

shown as they do not take into account the daytime worker population.

Quality of the local environment | 32

The longer term time trend of global average temperature rises associated with

climate change is shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17: Long-term trends in global average temperature

Source: [34] Note: Based on three observational datasets as shown in the key.

The proportion of MSOA areas (see Box 1) estimated to be highly vulnerable to

climate change related flood risk in Hackney is similar to the national average

(Figure 18). The proportion of areas estimated to be highly vulnerable to heat risk is

higher than the London and national average (Figure 19). The one MSOA in the City

of London is categorised as having a high vulnerability to both flooding and heat.

[52]

Quality of the local environment | 33

Figure 18: Estimated proportion of MSOA areas which are highly vulnerable to

climate change related flooding (2014)

Source: [52]. Note: Based on 28 MSOA areas in Hackney. The one MSOA area in the City of London

was also considered to be highly vulnerable, and is not shown for clarity.

Figure 19: Estimated proportion of MSOA areas which are highly vulnerable to

climate change related heat (2014)

Source: [52]

Note: Based on 28 MSOA areas in Hackney. The one MSOA area in the City of London was also

considered to be highly vulnerable, and is not shown for clarity.

Quality of the local environment | 34

7.6.4 Contaminated land

Comparative and time trend data relating to land contamination are not available.

Most land contamination in the UK is associated with areas which have previously

had some industrial use, such as Hackney.

7.6.5 Noise

Figure 20 shows that Hackney has higher levels of exposure to significant daytime

noise than the London and England averages, but similar to many of its statistical

peers.

The City has the highest rate of exposure in the country and much higher than the

London or national average. This is due to its location, at the heart of London, and

the density of development. However, please note that statistical significance cannot

be ascertained in making these comparisons as confidence intervals are not

available in published data.

Figure 20: Percentage of the population exposed to significant daytime road, rail and

air transport noise (2016)

Source: Public Health Outcomes Framework [54].

Notes: ‘Significant’ daytime noise is defined by WHO as 65dB or above. Confidence intervals not

provided.

Figure 21 shows that exposure to significant night-time noise is again higher in

Hackney than the England average, but similar to most of its statistical peers. Levels

of exposure in the City are much higher than in Hackney, London and England on

average. Although again, statistical significance of these comparisons cannot be

ascertained.

Quality of the local environment | 35

Figure 21: Proportion of the population exposed to significant night-time road, rail

and air transport noise (2016)

Source: Public Health Outcomes Framework.

Notes: ‘Significant’ night-time noise is defined by WHO as 55dB or above. Confidence intervals not

provided. [65]

The proportion of the population exposed to significant daytime and night-time traffic

noise is estimated to have reduced in Hackney between 2006 and 2016, from 17%

to 15% in the daytime (Figure 22) and 22% to 19% at night (Figure 23). This is in line

with London averages. The reductions are more significant in the City over this same

period, with a sharp fall from 42% to 28% in those affected by daytime noise and

from 48% to 28% in those affected by night-time noise.

Time trends in the health impact of occupational noise, estimated in the GBD study,

show a largely stable trend in Hackney and the City from 1992 to 2017. [4]

Quality of the local environment | 36

Figure 22: Percentage of the population exposed to significant daytime road, rail and

air transport noise (2006-16)

Source: Public Health Outcomes Framework [54].

Notes: ‘Significant’ daytime noise is defined by WHO as 65dB or above. Confidence intervals not

provided.

Figure 23: Proportion of the population exposed to significant night-time road, rail

and air transport noise (2006-16)

Source: Public Health Outcomes Framework. [65]

Notes: ‘Significant’ night-time noise is defined by WHO as 55dB or above. Confidence intervals not

provided.

The rate of complaints about noise in Hackney is higher than both the England and

London average, and in the middle of Hackney’s statistical peers (Figure 25).

Camden, Wandsworth and Hammersmith and Fulham have lower rates, while

Lambeth and Islington’s rates are higher than that of Hackney.

Quality of the local environment | 37

There has been a downward trend in the rate of complaints about noise in Hackney

over recent years (Figure 25).

Figure 24: Rate of complaints per year per local authority about noise (per 100,000

population, 2015/16)

Source: Public Health Outcomes Framework. [54] Figures not available for the City of London

Figure 25: Rate of complaints per year per local authority about noise per 100,000

population (2010/11 - 2015/16)

Source: Public Health Outcomes Framework. [54] Figures not available for the City of London

Quality of the local environment | 38

7.7 Evidence and good practice

7.7.1 Air quality - outdoor

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published guidance on

air pollution in 2017. [63] Key recommendations from this guidance are summarised

in Box 2.

Box 2: Summary of NICE guidance NG70: Air pollution: outdoor air quality and

health [63]

● Include air pollution within local strategic plans and processes (including the

Local Plan, core strategy, transport plan, and health and wellbeing

strategies), with a focus on zero or low-emission travel.

● Consider air quality within plans for new developments or regeneration

programmes, ensuring appropriate steps are taken to reduce the need for

motorised travel and to minimise exposure to air pollution.

● Utilise Community Infrastructure Levy funding to implement air quality

monitoring and measures to reduce road traffic-related emissions.

● Considering ways to reduce or mitigate road-traffic-related air pollution,

including initiatives to reduce motorised vehicle trips, to encourage the use

of no or low emission vehicles, and to review tree and vegetation

management.

● Consider the implementation of local, potentially cross-borough clean air

zones, which act to promote zero or low emission travel and discourage

motorised vehicular travel.

● Ensure that air quality is considered within decisions around public sector

fleet procurement, and that the staff driving these vehicles are adequately

trained in how to drive in such a way as to minimise fuel consumption and

air pollution.

● Provide both the public and health professionals with information about the

impacts of poor air quality on health, and how to reduce local air pollution

and minimise exposure to it.

● Develop infrastructure to support and encourage cycling and other forms of

active travel.

Quality of the local environment | 39

Figure 26 and Figure 27 below show the source of two major pollutants locally.

Figure 26: Expected sources of oxides of nitrogen in Hackney (left) and City of

London (right) (2016, released 2019)

Source: GLA [64]

Figure 27: Expected sources of PM2.5 particulates in Hackney (left) and City of

London (right) (2016, released 2019)

Source: GLA [64]

Quality of the local environment | 40

Table 3: Expected sources of PM2.5 particulates and oxides of nitrogen in Hackney

and City of London (2016, released 2019)

Category

Subcategory

Sources

Nitrogen oxides

(NOx)

Particulates (PM2.5)

Hackney

City of

London

Hackney

City of

Londo

n

Transport

Aviation

Aviation

0.0%

1.0%

0.0%

0.1%

Transport

Rail

Freight, Passengers

0.8%

-

0.3%

-

Transport

River

Commercial,

Passengers, Small

Vessels

0.1%

15.7%

0.0%

5.4%

Industrial and

Commercial

Heat and

Power

Generation

Combustion from Gas,

Coal, Oil Fuels

15.8%

41.8%

3.8%

11.9%

Industrial and

Commercial

Industrial

Processes

Part As/Bs, NRMM from

Industrial Sites

0.7%

1.0%

2.1%

0.8%

Industrial and

Commercial

Construction

Construction Dust,

NRMM from Construction

Sites

8.9%

2.5%

17.1%

6.5%

Industrial and

Commercial

Waste

Landfill, WTS, Small

Scale Waste Burning,

STW

0.0%

0.0%

0.2%

0.0%

Industrial and

Commercial

Cooking

Cooking from

Commercial Outlets

-

-

28.2%

53.3%

Domestic

Heat & Power

Generation

Combustion from Gas,

Coal, Oil Fuels

9.2%

0.2%

6.3%

0.1%

Domestic

Biomass

Wood Burning

-

-

9.3%

0.0%

Resuspension

-

-

1.0%

0.7%

Miscellaneous

0.2%

0.0%

2.4%

0.8%

Transport

Road

Motorcycle

0.3%

0.3%

0.4%

0.5%

Transport

Road

Taxi

4.1%

7.4%

2.1%

6.5%

Transport

Road

Car - Petrol

4.3%

0.9%

6.4%

1.9%

Transport

Road

Car - Diesel

13.9%

4.0%

7.6%

2.7%

Transport

Road

Car - Electric

-

-

0.0%

0.0%

Transport

Road

Van / Minibus

9.6%

4.9%

5.3%

3.5%

Transport

Road

TfL Bus

17.2%

8.7%

3.5%

2.4%

Transport

Road

Non-TfL Bus and Coach

2.9%

4.6%

0.5%

0.8%

Transport

Road

HGV - Rigid

10.0%

6.2%

2.8%

1.9%

Transport

Road

HGV - Artic

2.0%

0.9%

0.5%

0.2%

Source: GLA [64]

Published quality standards underpinning this guidance identify four priority areas

for action, as described below. [63]

● Quality statement 1: Local authorities identify in the Local Plan, local transport

plan and other key strategies how they will address air pollution, including

enabling zero- and low-emission travel and developing buildings and spaces

to reduce exposure to air pollution.

Quality of the local environment | 41

● Quality statement 2: Local planning authorities assess proposals to minimise

and mitigate road-traffic-related air pollution in planning applications for major

developments.

● Quality statement 3: Public sector organisations reduce emissions from their

vehicle fleets to address air pollution.

● Quality statement 4: Children, young people and adults with chronic

respiratory or cardiovascular conditions are given advice at routine health

appointments on what to do when outdoor air quality is poor.

Each of the four quality statements has a number of suggested indicators that can be

used by local areas to monitor progress. These include measures such as mean

particulate and NO2 concentrations, levels of active or low/zero-emission journeys

taken by local residents, rates of specific hospital attendances or admissions, as well

as evidence drawn from key local documents.

NICE provides further guidance and information for a range of stakeholders around

the implementation of NICE quality standards at a local level. [66]

Table 4 summarises key recommendations from the Royal College of Physicians

(RCP) and Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) on reducing the

health risks of poor air quality, at societal and individual level. This shares many of

the recommendations covered by the NICE guidance described above.

Quality of the local environment | 42

Table 4: Air quality - recommendations from the RCP and RCPCH

Broad

area

Summary of recommendations

Societal

action

● Put the onus on polluters. Political leaders at a local, national

and European level must introduce tougher regulations, including

reliable emissions testing for cars.

● Local authorities need to act to protect public health when air

pollution levels are high. When these limits are exceeded, local

authorities must have the power to close or divert roads to reduce

the volume of traffic, especially near schools.

● Monitor air pollution effectively. Air pollution monitoring by

central and local government must track exposure to harmful

pollutants in major urban areas and near schools. These results

should then be communicated proactively to the public in a clear

way that everyone can understand.

● Quantify the relationship between indoor air pollution and

health. Understanding of the key risk factors and effects of poor

air quality in our homes, schools and workplaces needs to be

improved. A coordinated effort is required to develop and apply

any necessary policy changes.

● Define the economic impact of air pollution. Air pollution

damages not only physical health, but also economic wellbeing.

Further research needs to be conducted into the economic

benefits of well-designed policies to tackle it.

● Lead by example within the NHS. The health service must no

longer be a major polluter; it must lead by example and set the

benchmark for clean air and safe workplaces.

Individual

action

● Use alternatives to car travel, preferably taking the ‘active’ option:

bus, train, walking and cycling.

● Aim for energy efficiency in homes.

● Keep gas appliances and solid fuel burners in good repair.

● Learn more about air quality and stay informed.

Source: RCP, 2016 [10]

In March 2019, Public Health England (PHE) published an evidence review of a

broad range of interventions aimed at improving outdoor air quality. Reviews of

intervention evidence were conducted across five areas of potential action: vehicles

and fuels; spatial planning; industry; agriculture; and behaviour change. This

process highlighted the highly variable quality and quantity of the available research

evidence relating to air quality interventions, with high quality evidence notably

lacking across the areas of vehicle and fuel, spatial planning and behaviour change.

Despite this, PHE was able to provide a number of recommended actions across the

five areas, as well as a number of more general, cross-cutting approaches. They

also identified seven general principles that can help to guide action on air quality at

both the local and national level [67]:

1. Different air pollutants should be considered and tackled together

2. Local authorities need to work together

Quality of the local environment | 43

3. Effective strategies require a coherent approach

4. Everyone has a role to play

5. It is better to reduce air pollution at source that to mitigate the consequences

6. Improving air quality can go hand in hand with economic growth

7. As action is taken some groups may need particular support

While vegetation and tree planting is thought to have a positive impact on air quality,

a review by NICE and a recent report prepared for Defra identified a lack of

conclusive evidence, suggesting that the overall effect on urban air quality is likely to

be low. [68] [63] Some planting approaches may in fact worsen air quality in the

immediate vicinity. As such, approaches to planting should be considered at a local

level, with a focus on species selection, placement and pruning schedules.

Approaches to reducing specific emissions

Industrial standards for vehicle engines are based on international standards and, as

such, there is little that can be done at local level to directly influence these. Older,

more polluting vehicles can be retrofitted with either particulate or selective catalytic

reduction filters, which can reduce levels of various emissions from anywhere

between 20% and 90%. [69]

There is mixed evidence regarding the impact of low emission zones (LEZ) operating

in a number of European cities in relation to levels of key pollutants. [70] [71] This

may be related to the varying ways in which these schemes are implemented,

monitored and enforced. The Greater London LEZ, implemented from 2008, has

focused on heavy commercial vehicles. While there have been good levels of

compliance, the impact on overall air pollution levels has been modest, with no

discernible changes in NOx concentrations. [72]

Encouraging modal shift in transport also offers a key opportunity to reduce air

pollution attributable to motorised vehicles, both in terms of exhaust emissions and

particulate matter linked to tyre and brake wear. In a recent study, it was estimated

that by taking necessary steps to meet the Government’s Cycling and Walking

Investment Strategy targets in England, more than 8,300 deaths attributed to air

pollution could be prevented over ten years, and annual savings of £567m could be

achieved for the national economy. This financial saving is five times that estimated

over a 10 year period from implementation of the Government’s Clean Air Zones in

England. [73]

Open fires and wood-burning stoves have risen in popularity over recent years.

While London has the lowest regional rate of domestic solid fuel burning in the UK,

this is still the biggest contributor to particulate matter concentrations, accounting for

up to 31% of the urban derived PM2.5 in the capital. [74] [2] Education around fuel

choice, stove efficiency and chimney maintenance are important in reducing

emissions resulting from solid fuel burning. [3] Voluntary schemes, such as the

Defra-backed ‘Ready to Burn’ scheme, aim to make it easier for consumers to

purchase suitable fuel. [3] In 2022, new tougher emissions standards will come into

effect for all new domestic stoves. [3]

Quality of the local environment | 44

Approaches to mitigate individual health risks from poor air quality

Morbidity and mortality rise during air pollution incidents, and this justifies efforts to

inform the public and groups at particular risk. Avoidance strategies should form an

important part of any public education approach. [63]

Health and social care services have a key role to play in providing information

directly to vulnerable people known to them, as well as a wider role in reducing their

own emissions (see Error! Reference source not found. for a local example).

Box 3: Case Study - Barts Health Action on Air Pollution

The Barts Health Action on Air Pollution: Collaboration and Public Health at Scale

project was a three year programme designed to take a comprehensive trust-wide

approach to air quality. Alongside interventions to increase green space on trust

sites, encourage modal shift and reduce fleet emissions, a number of the

programme strands involved the delivery of patient interventions by clinicians and

other healthcare staff.

Programme

strand

Key deliverables

Warm and well

Community-based trust staff acted as trusted

messengers to share key health messages with those most at

risk of fuel poverty and in areas with high average

domestic gas use.

Protecting

patients

Clinicians and community staff were empowered to give their

vulnerable patients practical advice on how to access key

information around daily pollution levels, reduce

their exposure and take action to protect themselves.

Waltham Forest

pharmacies

10 pharmacists in Waltham Forest gave practical advice to

patients in ‘at risk’ groups, and distributed 1,000 Cleaner Air

packs to patients collecting certain

medication.

The evaluation report of the programme identified that delivering messages

relating to air quality via health care staff was up to 33% more effective than simply

providing patients with relevant resources to consult themselves.

Source: Barts Health NHS Trust, 2016

Schemes such as airText provide free air quality forecasts by text, voicemail, twitter

and an app. These resources allow members of the public to monitor local air quality,

and to take appropriate steps to mitigate against the impacts of periods of high

pollution levels. [75]

A 2014 evaluation of an air quality alert programme in Canada identified reductions

in respiratory morbidity, but found impact on cardiovascular morbidity or mortality, or

on respiratory mortality. [23] One relatively small study conducted in Wales did

identify a near doubling of hospital admissions among patients with a range of long-

term conditions who received air quality alerts over a two year period, with a four-fold

Quality of the local environment | 45

increase in respiratory admissions. The latter study highlights the need to ensure

that the public, and particularly high risk groups, have clear advice about appropriate

actions in light of air quality alerts. [76]

The NHS Sustainable Development Unit has produced a tool to support

commissioning organisations to calculate the impact their transport has on health,

the environment, and on finances. [77]

There are several route planners available which allow members of the public to

optimise their journey to avoid areas with higher levels of pollution – this includes

Londonair.org.uk. These tools can be complemented with further messaging around

strategies to reduce exposure, such as travelling outside of peak times when

possible and walking further away from traffic on the pavement.

Beyond this, new technology linked to smartphones increasingly allows members of

the public to have access to personal air pollution monitors. However, there are