'94A0=>4?D:1&0990>>009:CA4770'94A0=>4?D:1&0990>>009:CA4770

&$&0990>>00$0>0,=.3,9/=0,?4A0&$&0990>>00$0>0,=.3,9/=0,?4A0

C.3,920C.3,920

,>?0=>&30>0> =,/@,?0%.3::7

"$#"$&%"$%#"!%&*!%#"$&&"$#"$&%"$%#"!%&*!%#"$&&

'%&$&(%"&$ ! !F%'!%'%&$&(%"&$ ! !F%'!%

094>0 :=,B06

'94A0=>4?D:1&0990>>009:CA4770

/8:=,B06A:7>@?60/@

:77:B?34>,9/,//4?4:9,7B:=6>,?3??;>?=,.0?0990>>000/@@?6+2=,/?30>

#,=?:1?30@>490>>,B#@-74.$0>;:9>4-474?D,9/?34.>:88:9>9A4=:9809?,7%?@/40>

:88:9> ,=60?492:88:9>"?30=9?0=9,?4:9,7,9/=0,%?@/40>:88:9>%;:=?> ,9,20809?

:88:9>,9/?30%;:=?>%?@/40>:88:9>

$0.:8809/0/4?,?4:9$0.:8809/0/4?,?4:9

:=,B06094>0"$#"$&%"$%#"!%&*!%#"$&&'%&$&(%"&

$ ! !F%'!% ,>?0=>&30>4>'94A0=>4?D:1&0990>>00

3??;>?=,.0?0990>>000/@@?6+2=,/?30>

&34>&30>4>4>-=:@23??:D:@1:=1=00,9/:;09,..0>>-D?30=,/@,?0%.3::7,?&$&0990>>00$0>0,=.3,9/

=0,?4A0C.3,920?3,>-009,..0;?0/1:=49.7@>4:949 ,>?0=>&30>0>-D,9,@?3:=4E0/,/8494>?=,?:=:1&$

&0990>>00$0>0,=.3,9/=0,?4A0C.3,920:=8:=0491:=8,?4:9;70,>0.:9?,.??=,.0@?60/@

&:?30=,/@,?0:@9.47

,8>@-84??49230=0B4?3,?30>4>B=4??09-D094>0 :=,B0609?4?70/"$#"$&%"

$%#"!%&*!%#"$&&'%&$&(%"&$ ! !F%'!%

3,A00C,8490/?30G9,7070.?=:94..:;D:1?34>?30>4>1:=1:=8,9/.:9?09?,9/=0.:8809/?3,?

4?-0,..0;?0/49;,=?4,71@7G77809?:1?30=0<@4=0809?>1:=?30/02=00:1 ,>?0=:1%.409.0B4?3

,8,5:=49$0.=0,?4:9,9/%;:=? ,9,20809?

%D7A4,&=09/,G7:A, ,5:=#=:10>>:=

)03,A0=0,/?34>?30>4>,9/=0.:8809/4?>,..0;?,9.0

011=0D=,3,8,=>E46@>

..0;?0/1:=?30:@9.47

4C40&3:8;>:9

(4.0#=:A:>?,9/0,9:1?30=,/@,?0%.3::7

"=4249,7>429,?@=0>,=0:9G70B4?3:H.4,7>?@/09?=0.:=/>

CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY IN SPORT: THE ILLUSTRATIVE

CASE OF THE GERMAN MEN’S BUNDESLIGA

A Thesis Presented for the

Master of Science

Degree

The University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Denise Morawek

May 2024

ii

Copyright © 2024 by Denise Morawek

All rights reserved.

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to my advising committee for the continuous support and belief in my

proposal and ability.

iv

ABSTRACT

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has become a pivotal aspect for companies

and governments, exceeding mere risk management to create opportunities and enhance

overall performance. While the concept of CSR in sports is relatively recent, its

significance is growing, especially in Germany’s sport industry. The Bundesliga, one of

the world’s top football leagues, showcases a unique CSR landscape shaped by societal,

economic, and political drivers. Societal motives reinforce regional identity, economic

strategies target customer retention, and political actions, including governmental

programs and football governing bodies’ initiatives, shape CSR endeavors. Germany’s

distinctive 50+1 rule, albeit with exceptions, highlights the fan-centric model. The recent

integration of mandatory sustainability guidelines in Bundesliga licensing regulations

further emphasizes the league’s commitment to CSR, making it a compelling subject for

in-depth analysis.

This research intends to comprehensively investigate the prevailing standards of CSR in

the 1. German Men’s Bundesliga, specifically shedding light on potential differences in

focus areas and standards among the 16 consistent clubs during the 2021-2022 season. The

data collection process involved examining publicly available CSR reports, and club

websites, and employing document analysis. Additional analysis focused on the complex

interplay between factors such as financial performance, sponsorship investments,

consumer social response, and CSR initiatives. The study then categorizes clubs and

defines CSR standards utilizing an adapted CSR pyramid and Stakeholder Management

Capability (SMC) scale based on Carroll (1979), Carroll and Buchholtz (2014), and Visser

(2006). Noteworthy findings include a dominant focus on environmental and sustainability

aspects among many clubs, indicating a shared commitment to addressing contemporary

challenges. Although such a commitment to sustainability is exemplary, the study

emphasizes the need for clubs to broaden their focus to include more diverse CSR

approaches.

The study acknowledges the unique challenges and opportunities faced by each club and

emphasizes the significant progress made by clubs in integrating CSR. Additionally, the

v

results indicate an existent awareness that positions the Bundesliga clubs on the path to

continuous improvement.

Ultimately, this research contributes to the evolving understanding of CSR in the context

of sports, specifically regarding the standards of CSR in specific football clubs.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE – INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 1

Topic Relevance and Problem Statement ....................................................................... 1

CHAPTER TWO – LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................... 3

Defining Corporate Social Responsibility ...................................................................... 3

CSR in Sport ................................................................................................................... 6

The Landscape of CSR in German Sport ........................................................................ 7

CSR in the First German Football League (1. Bundesliga) .......................................... 10

Societal Drivers ......................................................................................................... 11

Economical Drivers .................................................................................................. 12

Political Drivers ........................................................................................................ 13

Theoretical Background ................................................................................................ 15

Prominent Theories ................................................................................................... 16

Conceptualization of a sport-based CSR framework ................................................ 20

Classification of CSR focus areas ............................................................................. 21

Financial Performance .............................................................................................. 23

Consumer Social Response (CnSR).......................................................................... 23

Research Questions ....................................................................................................... 25

CHAPTER THREE – METHODOLOGY ....................................................................... 26

Sample Size ................................................................................................................... 26

Data Collection ............................................................................................................. 29

CHAPTER FOUR – RESULTS ....................................................................................... 31

Frameworks................................................................................................................... 31

Classification of CSR focus areas ................................................................................. 32

Financial Performance .................................................................................................. 46

Consumer Social Response (CnSR).............................................................................. 47

CHAPTER FIVE – DISCUSSION ................................................................................... 56

CHAPTER SIX – CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION .................................. 65

Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 65

Recommendations ......................................................................................................... 66

Future Research ............................................................................................................ 66

Limitations .................................................................................................................... 67

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................. 69

APPENDICES .................................................................................................................. 86

VITA ............................................................................................................................... 113

vii

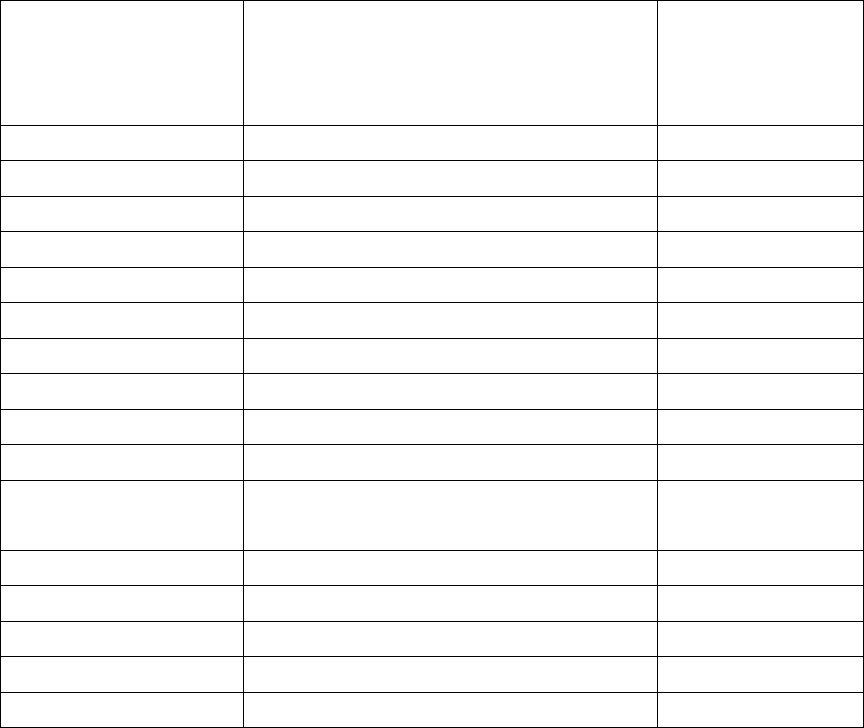

LIST OF TABLES

Table 3.1. The clubs of the 2021-2022 season of the 1. German Bundesliga .................. 27

Table 3.2. The respective foundations of the clubs .......................................................... 34

Table 4.1. An accumulative overview of initiatives divided by focus area and club ....... 34

Table 4.2. Overview and Ranking of the Financial Performance ..................................... 34

Table 4.3. Overview and Ranking of the Sponsors and Sponsorship Investments ........... 50

Table 4.4. Overview and Ranking of the Stadium Capacity ............................................. 52

Table 4.5. Overview and Ranking of the Popularity ........................................................ 55

Table 5.1. Definition and Comparison of CSR standards within the defined clubs ......... 34

viii

LIST OF FIGURES

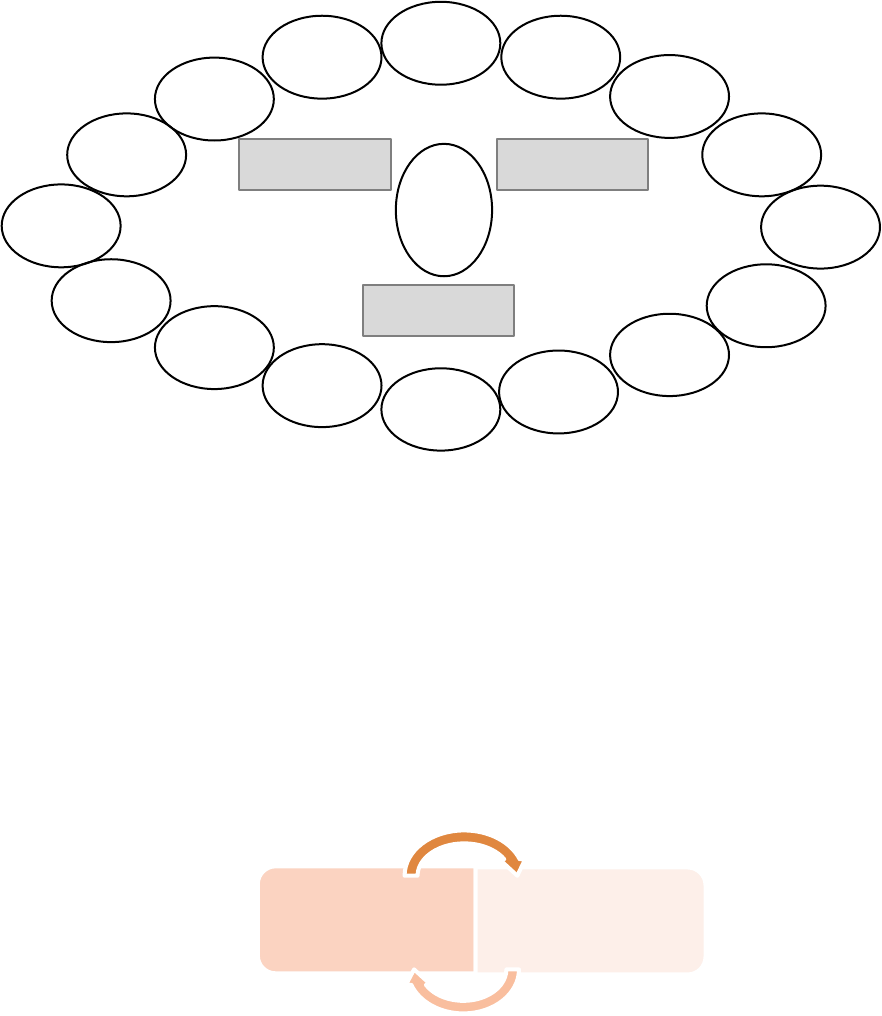

Figure 2.1. Non-hierarchical stakeholder map of a German Football club ...................... 17

Figure 2.2. The Stakeholder Symbiosis ............................................................................ 17

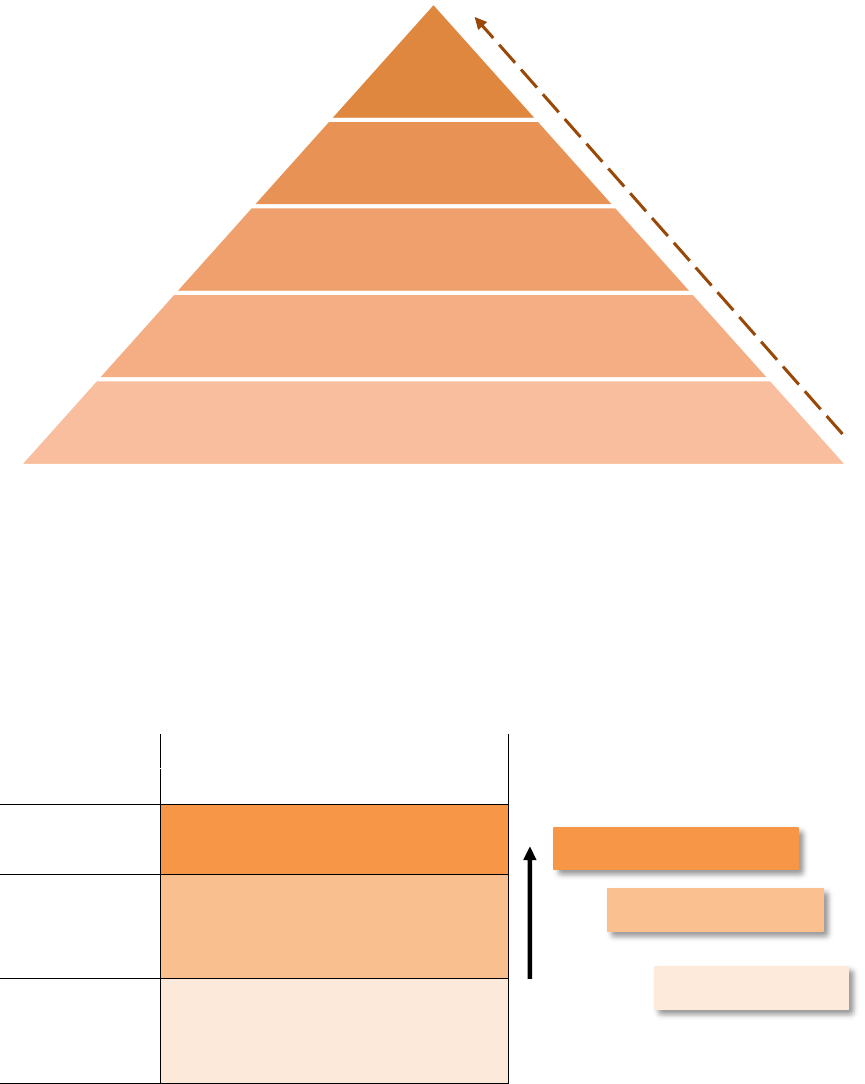

Figure 2.3. Conceptualization of a sport-based CSR Framework .................................... 17

Figure 2.4. Stakeholder Management Capability Scale (SMC) ........................................ 22

1

CHAPTER ONE – INTRODUCTION

Topic Relevance and Problem Statement

Sunil Misser, the Head of Global Sustainability Practice for Pricewaterhouse

Coopers LLP, more commonly known as “PwC,” once said: “Corporate Social

Responsibility (CSR) is not just about managing, reducing and avoiding risk, it is about

creating opportunities, generating improved performance, making money and leaving the

risks far behind” (as quoted in Thacker, 2020). The concept has repeatedly been identified

as a perpetual concern for companies and governments when trying to adapt throughout

the past decades (Welford, 2004). Moreover, it has become apparent to companies

worldwide that stakeholders are not simply just shareholders anymore, but considerably

consist of a much larger group of constituents (Babiak, 2010). Dating back to as early as

1990, the concept of CSR has been proven to not only improve a firms economic and

financial performance but also its reputation and thus its brand equity (Godfrey, 2009; Kim

& Manoli, 2022). While the importance of CSR has significantly transformed the

management and organizational business side, the concept has just reached the sport

industry a few years ago (Walker & Kent, 2009; Walzel et al., 2018). Even though CSR

reporting is yet to become mandatory in most countries, various multinational corporations

(“MNCs”) in the sport sector, such as Nike, have already been incorporating information

about their CSR activities in either their annual reports or in a separate statement as well

as related information on their programs on their websites (Annual Reports and Websites;

Nike, 2022; Walker & Kent, 2009).

Utilizing CSR in the sport industry is crucial when cultivating an effective

connection between the organization/club, the team and its players, and the community

(Franco et al., 2021; Ladhari et al., 2022; Moore, 2019). Many organizations still face a

perpetual distrust in their practices and measures within the CSR context (Wan Yusoff &

Alhaji, 2012). Therefore, sport organizations and their respective CSR practices experience

a greater demand from the public regarding their transparency, accountability, and

comparability (Fifka & Jäger, 2020). Consequently, some organizations have been

implementing new policies regarding their CSR performance over the past few years. For

2

example, to improve their transparency, the Adidas Group has been publishing a CSR

report covering their environmental, societal, and cultural programs/ investments each year

since 2000 (Adidas Group, 2017).

Another significant example within the sport industry is Germany’s men’s soccer

league (hereafter “Bundesliga”). It is one of the most successful sport leagues in the world

and the second strongest league in world football after the English Premier League

(Furniss, 2023). Within the league there are various CSR activities that clubs participate

in, some examples include the promotion of public transport (i.e., a combination of stadium

entrance tickets with the free use of public transportation), the use of Environmental

Management Systems, the promotion of green electricity including photovoltaic, the

support of community members in need (e.g., by donations or drives), support of

international peace campaigns or the integration of children membership clubs. This study

is focused around defining and examining the CSR standards of the clubs within the 1.

German Bundesliga and each of the clubs’ CSR activities. Furthermore, it explores the

extent to which CSR has been implemented by each club by categorizing the present CSR

standards into the levels of a newly established sport-based CSR framework. The

framework was adapted from Carroll and Buchholtz (2014) and Visser (2006). The levels

include economic, legal and political, ethical, societal and regional, and philanthropic

responsibilities (Figure 2.3). Additionally, the Stakeholder Management Capability

(“SMC”) scale, established by Carroll and Buchholtz (2014), was used to typologize the

clubs’ level of stakeholder management into rational, process, and transactional

relationship building capabilities (Figure 2.4).

3

CHAPTER TWO – LITERATURE REVIEW

Defining Corporate Social Responsibility

The term “Corporate Social Responsibility” (CSR) has broadly existed for over

4,000 years (Visser, 2015). However, the concept used in modern days goes back to the

mid-late 1800s and the Industrial Revolution when one of the rising concerns was working

conditions and how those interrelated with the worker’s productivity (Carroll, 2009). Yet,

during this era, the concept of CSR was arguably more based on economic reasons, rather

than charitable ones. Once industrialists realized the power behind the philanthropic side

of business, CSR awareness increased, leading to immediate action of businesses regarding

their social and environmental activities (Stutz, 2015). Examples include the revision of

labor laws and the founding of schools to increase access to education (Munro, 2020).

Paternalism is recognized as one of the earliest forms of CSR during the century. The

theory of paternalism was also utilized during the “Pullman experience,” operated by

George M. Pullman; an industrial town developed in Chicago that served as a showcase of

enlightened management due to its use of appearance standards, living spaces, working

conditions, and more. The city also established certain social institutions and community

parks within its borders to uphold its social responsibility (Carroll et al., 2022). Even

though such experiments broadened social consciousness, many researchers refer to the

Great Depression as one of the main initiating factors for more social and corporate

accountability (Carroll, 2009). A more pluralistic society and the dispersion of ownership

are inevitably additional components to the change in perspectives (Hay & Gray, 1974).

Nevertheless, the modern concept of Corporate Social Responsibility was raised in the

1950s with R. Bowen’s book “Social Responsibilities of the Businessman”, which is

viewed as the landmark of the present-day term (Latapí Agudelo et al., 2019).

However, unlike its American and British counterparts, Germany’s integration of

CSR commenced later due to its historical evolution. CSR in Germany holds its roots in a

rich tradition of socially responsible entrepreneurship, tracing back to the industrialization

era (Hiß, 2009). Germany, a primarily agrarian nation until the late 19

th

hundreds, despite

initial efforts, only advanced once rapid industrialization propelled it to become the world’s

4

second industrial power by World War I (Habisch & Wegner, 2005). By this time, the state

was seen as the driving force behind modernization: it provided infrastructure, repressed

labor movements, introduced social security, and integrated an old-age pension system

(Habisch & Wegner, 2005) – ultimately, ensuring that the interrelatedness of the state and

social security benefited businesses (Berthoin et al., 2009). Nonetheless, early industrial

practices lacked additional protective measures (Hiß, 2009). Issues such as labor

exploitation and environmental degradation continued until pioneers such as Werner von

Siemens, Alfred Krupp, and Ernst Abbe recognized the adverse effects of the system (Hiß,

2009). Wanting to improve these conditions, they started to reduce workloads as well as

offer complimentary social security measures to their employees (Hiß, 2009). By the end

of the 19

th

century, Reichskanzler Otto von Bismarck had formalized such initial voluntary

practices into implicit legal regulations (Habisch & Wegner, 2005). His social legislation

marked a significant turning point in German history, not only laying the groundwork for

the modern welfare state but also setting the foundation for CSR in Germany (Hiß, 2009).

In the years post World War II, a distinctive institutional framework, known as

“Deutschland AG,” emerged (Hiß, 2009). It integrated economic growth with social

equality. By encompassing diverse regulations such as the Co-Determination Act, training

systems promoting skill enhancement, and trust-based inter-company relationships, the

framework fostered implicit commitment and installed a concept of social responsibility

among institutions (Berthoin et al., 2009). However, when the “Deutschland AG” eroded,

the binding effect of institutions implying corporate responsibility weakened. As a result,

the landscape of corporate constitutional law changed significantly (Hiß, 2009). Moreover,

the introduction of the Corporate Control and Transparency Act (“KonTraG”) in 1998

brought about a fundamental change in corporate governance in Germany (Hiß, 2009).

KonTraG marked the shift from the stakeholder view of the firm by prioritizing shareholder

interests over stakeholder concerns; thereby, altering the legal landscape and diminishing

the implicit responsibility of companies towards broader societal and economic interests

(Berthoin et al., 2009). KonTraG initiated the transition from a mandatory institutionalized

system of responsibility to the new era of explicit voluntary CSR commitments of

companies (Hiß, 2009). Companies responded by participating in international initiatives,

5

engaging in national or global alliances, or establishing internal CSR departments (Hiß,

2009). This transformative journey signifies a broader evolution in corporate culture and

practice (Berthoin et al., 2009). CSR in Germany showcases a progression from early

socially responsible entrepreneurship to the formalization of implicit responsibility,

followed by an institutionalized phase and finally, the current era of explicit voluntary CSR

(Berthoin et al., 2009; Habisch & Wegner, 2005; Hiß, 2009).

Furthermore, the environmental consciousness cultivated in Germany since the

1970s, evidenced by the proliferation of “green” movements and governmental

environmental programs, set the stage for the nation’s heightened awareness of

sustainability and therefore, explains the backdrop for the ecological evolution of CSR in

Germany (Habisch & Wegner, 2005). Over time, companies in Germany adjusted by

implementing foundations into their corporate structures. With philanthropy deeply

ingrained in the country’s ethos, foundations have, for example, supported human/ social

services, education and research programs, and sustainability-focused endeavors (Toepler,

1998). These entities not only provide financial backing, but also act as key drivers of

change, influencing policy-making and societal awareness, further solidifying Germany’s

position as a leading nation in philanthropic engagement and environmental stewardship

(Toepler, 1998). Today, Germany’s economy has seen a boost in philanthropic activities

with German foundations accounting for one-third of the total foundation spending in

Europe and Germans donating around €5.4 billion each year (Alberg-Seberich, 2013;

Corcoran, 2021).

However, CSR as a concept has yet to be defined concisely; especially in relation

to its social and environmental impact within the sport context (Biscaia, 2012). This is

based on the contention that CSR activities within a firm regularly exceed the rudimentary

approach of just trying to create further revenue streams/ increase operating profits (Chen

& Lin, 2020). The focus of these activities usually lies in establishing a good corporate

image/ performance in the eyes of the stakeholders. This includes ensuring their

informational needs regarding factors such as human and animal rights, public health,

social safety, child labor, pollution, and other environmental or social issues are met

(Levermore, 2010). CSR and its reporting are therefore evidently indispensable when

6

wanting to meet, understand, and gain the trust of each stakeholder group (Liu & Schwarz,

2019; Morrison et al., 2018).

CSR in Sport

Even though the concept of CSR developed years ago and has become significant

within business and philanthropic leadership, the idea has just recently reached the sport

industry (Walker & Kent, 2009). Nevertheless, the literature surrounding the context of

CSR in sport, particularly CSR in professional sport organizations, has substantially grown

over the past years, allowing immense insights into a great variety of issues (Walzel et al.,

2018). These include the strategic implementation of CSR (Breitbarth et al., 2011),

financial benefits derived from implementing CSR (Inoue et al., 2011) or different forms

of CSR engagement, such as environmental sustainability (Trendafilova & Babiak, 2013;

Trendafilova et al., 2013).

When it comes to CSR, it is often argued that sport organizations do not differ from

other corporations and therefore, CSR is applied in the same context. However, Walker

and Kent (2009) argue that in the “sport industry CSR differs from other contexts as this

industry possesses many attributes distinct from those found in other business segments”.

In their study, they mention how sport teams experience higher connectivity to their local

community because of the way fans are affected and interrelated with a team’s success.

Schleef (2013) even goes so far as saying how the increased importance of sport within

today’s society has gained “the ability to influence change within communities around the

world” and Coskun et al. (2020) describe the different stakeholder influences in

comparison to regular businesses. The Olympics or the World Cup are perfect examples of

the truth behind these arguments; the location of the competition and the surrounding CSR

activities are crucial components of fan support as well as the final revenue (Franco et al.,

2021). Many fans condone FIFA for allowing the World Cup to be executed in Qatar due

to the country’s immense Human Rights violations (e.g., against LGBTQ+, women, etc.)

as well as their current labor laws which have continuously been compared to “modern

slavery” (Bennett & Vietor, 2022). This led to a decline in fan engagement, revenue

creation, and fan loyalty.

7

The fact that CSR within sport plays a different role than in other industries is even

more visible when looking at the concept behind sport organizations. They are not solely

just a business but a part of the community (Coskun et al., 2020; Lau et al, 2004; Walker

& Kent, 2009). Sport organizations are implicitly intertwined with the society and

community they are established in, a characteristic that is limited for other businesses

(Schleef, 2013; Steward et al., 2003). Moreover, the indirect consumption by fans

associated with the local sport organization is often an integral part of a city’s hospitality

income (Smith & Westerbeek, 2007). Fans who identify with a certain team are most likely

to want to attend games; therefore, spending money on local restaurants, hotels, souvenirs,

etc. (Koo & Hardin, 2008).

Hence, CSR in the sport industry has been increasingly characterized as a means to

bring more awareness to a larger array of social stances such as symbolism, sociability,

stakeholder theory, and community identification (Hunt et al., 1999; Melnick, 1994; Sutton

et al., 1997). Due to the strong affective connections of sport fans, CSR programs have

substantially surged within sport teams (Walker & Kent, 2009). This is also reflected in

teams’/ athletes’ websites and social media accounts which now proudly announce and

share whenever they are participating in a philanthropic activity. A great example is the

DFL Foundation, an initiative of the DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga e.V. and DFL GmbH.

The foundation was established as an umbrella organization that is responsible for the

social activities of the 1. and 2. Bundesliga in Germany. The foundation is described as

being “focused on Germany as a whole, to complement and link the most regional

commitments of clubs and players – specifically involved where football can use its

connective power in the best interest of society” (DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga, 2023a).

The Landscape of CSR in German Sport

Overall, the landscape of CSR in sports in Germany reflects a growing awareness

of the impact sport entities can have on society beyond the field or arena. However,

professional sport in Germany continues to face challenges when it comes to sustainability

and CSR (Breitbarth et al., 2011; Walzel et al., 2018). Issues in the construction of sport

facilities, CO₂ emissions due to massive mobility, or plastic waste at major events come at

8

a cost to people and the environment (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, 2023).

Pressure from civil society and politics is growing and as a result, both non-governmental

and governmental organizations are trying to make sport clubs and institutions more

accountable and transparent (Urdaneta et al., 2021).

Germany has implemented new strategies, regulations, and initiatives to combat

social and environmental issues within the context of CSR in sports (Andreae et al., 2021).

Consequently, the country’s CSR evolution, specifically in sports, has gained immense

momentum – for both, its political agenda and various other stakeholders in the sport

industry (Berthoin et al., 2007; Reiche, 2013). Sport organizations and clubs in Germany

increasingly focus on sustainability, for example, by implementing eco-friendly practices

in stadium operations, including reducing carbon emissions, waste management, and

renewable energy sources (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, 2023). Notably,

the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU)

funded a platform of the German Olympic Sports Confederation called the “Green

Champions 2.0 for sustainable sporting events” to provide organizations of various sizes

with specific recommendations on how to plan and organize events more sustainably

(Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, 2023). Additionally, sport organizations

engage in community-based initiatives (Trendafilova et al., 2017) such as supporting local

charities (Walzel, 2018), encouraging participation among underrepresented groups (Gieß-

Stüber et al., 2018), promoting mental health awareness and overall fitness (Raid, 2023),

and investing in youth development programs (Brettschneider, 2020). All of these

developments and the growing awareness in society are affecting decision-makers in sports

in Germany. Nowadays, companies often align their sponsorships and partnerships

strategically with their CSR goals – for example, by supporting a specific sport team or

event that lines up with their vision and mission (Breitbarth et al., 2011). Moreover,

individual athletes are progressively using their platforms to advocate for social issues,

environmental concerns, human rights, and more to bring about positive change (Filizöz &

Fişne, 2011).

This commitment to social and environmental transformation is showcased by a

variety of current German initiatives. “Our Football” is a fan initiative that represents a

9

commitment to the Paris Climate Agreement from top football clubs in Germany, from the

German Football League (DFL), the German Football Association (DFB), and from clubs

themselves. It calls for more sustainable match operations overall, including carbon

footprint assessments, emissions offsetting, setting environmental benchmarks, and supply

chain regulations for merchandise products (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales,

2023). Similarly, the WEED e.V. initiative sheds light on the supply chain and globalized

production of footballs. Under the motto of “All around the World”, the association

developed teaching material to raise awareness about ethically produced balls

(Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, 2023). Moreover, the UEFA and the DFB

ambitiously aim for the 2024 European Championship in Germany to be the “most

sustainable tournament to date” (DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga, 2023a).

In addition, the “Environment and Sport” advisory board convened by the BMU

advises the German federal government, monitors current research, and specifies concrete

goals for resource-conserving sport practices (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales,

2023). For example, the position paper “Sustainable Sport 2030” contains numerous

recommendations for action on how people and the environment can maintain a healthy

relationship in the long term when it comes to sport (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und

Soziales, 2023). These include the careful use of nature and the landscape, energy-efficient

and sustainably operated sport facilities, sustainable major sporting events and mobility

concepts as well as raising awareness of environmentally friendly and fairly-produced

sporting goods. Extending beyond football, the German Ski Association (DSV) provides

support with educational offers and environmental requirements (Deutscher Skiverband

(DSV), Snowboard Germany (SNBGER) & Stiftung Sicherheit im Skisport (SIS, 2024) –

highlighting a comprehensive approach toward sustainability. There is a recognition that

sports can be a powerful tool for positive social change, and organizations and athletes are

actively leveraging their influence to drive meaningful initiatives and support various

social causes. While prevailing CSR initiatives within specific sport industries,

organizations, and clubs have been identified, they have yet to be compared and contrasted,

thus, encouraging an analysis of ongoing practices within specific sport leagues such as the

1. German Men’s Bundesliga.

10

CSR in the First German Football League (1. Bundesliga)

Since CSR programs serve to positively affect the local community, sport

organizations have been incorporating them to influence sport consumers to potentially

transfer such positive emotions to the organization (Steward et al., 2003). Social

commitment has become a matter for sport organizations around the globe (Bradish &

Cornin, 2009; Breitbarth et al., 2011), with the German Bundesliga being only one

example. Over the past decade, German football and the Bundesliga have grown

immensely economically (Deutscher Fußball-Bund, 2020). The league doubled its revenue,

reaching a high of €4 billion in the 2018/19 season, right before Covid-19 hit (Zeppenfeld,

2023).

Although the Bundesliga is economically comparable to a medium-sized company,

the expectations differ greatly: today’s teams do not only have to succeed in their respective

sport, but also oblige other stakeholder requirements (Coskun et al., 2020). Fans, club

members, politicians, sponsors, investors, etc., increasingly expect the Bundesliga to

assume social and environmental responsibility encouraging clubs to invest in their own

foundations and CSR departments (Ludwig, 2022). Furthermore, the Bundesliga clubs are

spread out throughout the country. They are usually deeply rooted in their region,

potentially explaining differences in their commitment and CSR focus areas (Ludwig,

2022).

In the Bundesliga, CSR is driven by a variety of factors. Reiche (2013) explored

the interconnectedness of societal, economic, and political drivers behind CSR within the

Bundesliga. He explained how societal motives incentivize the clubs to participate in CSR

initiatives as they aim to bolster regional identity in the age of globalized football and

actively position themselves as societal role models, leveraging football’s immense reach

and influence (Breitbarth & Rieth, 2012; Underwood et al., 2001). From an economic

perspective, the CSR endeavors of the clubs are strategic, fostering an environment that

attracts sponsors and enhances customer loyalty, thus ensuring sustained financial viability.

Additionally, the globalization of football highlights the political drivers of clubs. Political

incentives and interventions, governmental action, and the oversight of football governing

11

bodies, such as the DFL and DFB in Germany, necessitate the integration of evolving

regulations and international standards of CSR.

Societal Drivers

In Germany, sport clubs are classified as “eingetragene Vereine” (e.V.), which

could be translated to registered associations or incorporated societies (Grenier, 2019). As

non-profit organizations, they are not driven by economic goals but rather aim to benefit

society and the common good. These associations are recognized as charitable entities in

Germany and therefore, receive support from the state in the form of tax exemptions and

trainer and volunteer allowances. Only those associations that are officially recognized by

their responsible tax office as such non-profit associations, within the meaning of tax

regulations, enjoy those tax benefits. The recognition of “Gemeinnützigkeit” (i.e., non-

profit status) is therefore of particular importance for every association in Germany

(Ministerium für Finanzen Baden-Württemberg, 2022). Here, the term “Gemeinnützigkeit”

is simply translated as non-profit, however that does not capture its full meaning. In

Germany, “gemeinnützige Vereine” must contribute the public and societal wellbeing by

law and tradition (Grenier, 2019). For the context of this study, it is thus important to note

that sport clubs in Germany have a particular cultural, historical, and legal context that

elevates stakeholder expectations. Thus, even when teams of the Bundesliga are organized

as limited or joint-stock company, they are a subsidiary of the “eingetragener Verein”. One

example is the relationship between the FC Bayern München AG and the FC Bayern

München e.V. (DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga, 2023b).

This unique setting of sport clubs in Germany aligns with Reiche’s (2013) findings

on societal drivers. Reiche higlighted that strengthening regional identity is a driving force

behind clubs’ CSR projects. He also discussed how commercialization and

internationalization of football in Germany have contributed to regional emphasis and how

that is evident in the transition of stadium naming rights from reflecting regional identity

to sponsorship by corporate entities. Other sources, such as Taylor (2006), identified the

growing number of foreign players in Bundesliga teams to be a leading cause of a perceived

detachment between fans and players. This shift seems to alter the traditional local fabric

12

of the sport. Nonetheless, many of the clubs have evolved within their regional

communities. As a result, fans often have generational affiliations with their local team

(Gehrmann, 1999). Based on this historical foundation, clubs are deeply rooted in their

regions. The clubs in the Bundesliga are recognized as more than just entities; they

represent a collective identity, shared history, and regional pride for their fans (Hamm,

1998). Recognizing the importance of such local support, the clubs within the Bundesliga

often specifically aim at implementing CSR projects that support their regional

communities (Breitbarth et al., 2011; Trendafilova et al., 2017; Walzel, 2018). Moreover,

Reiche (2013) described how clubs increasingly recognize their potential to impart values

and influence societal behavior among their supporters. One strategy used by clubs is to

integrate their team’s identity into educational curricula in their communities through

partnerships with schools, certain workshops/ programs specifically offered to schools, or

educationally-focused campaigns with local schools. Additionally, the clubs aim to

counterbalance adverse perceptions of football and alleviate any negative effects scandals

may have on their credibility by actively engaging in social initiatives (Park et al., 2014).

Economical Drivers

The next driver identified by Reiche (2013) revolves around customer retention

strategies, particularly focusing on children as a key demographic. Based on their historical

foundations and regional influence, clubs have realized the significant role that children in

their communities can play – not only for social support – but as potential lifelong investors

(Andreae et al., 2021). When utilizing early connections with young fans, clubs can convert

them into long-term customers (McDonald et al., 2015). By engaging children in football

early on, clubs benefit from the opportunity of scouting and recruiting future players at an

early age (Sweeney et al., 2021). Furthermore, clubs use specific CSR measures to improve

their attractiveness and generate positive publicity, either to increase the favorable

exposure of current sponsors or to gather the attention of prospective ones (Reiche, 2013).

Consequently, clubs within the Bundesliga often align their CSR initiatives with strategic

and business goals (Breitbarth et al., 2013; Reiche, 2013).

13

Political Drivers

The final driver behind CSR in the Bundesliga is governmental action. Germany

has vigorous federal policies regarding eco-friendly practices in place such as the feed-in

tariff, for example, to incentivize the adoption of renewable energy sources (Mendonca,

2009). Sport organizations often need legitimacy and goodwill from their governments to

receive certain financial benefits, for example, tax breaks (Lucidarme et al., 2017) as do

the clubs within the Bundesliga. By establishing positive relationships with local

politicians, clubs ensure political support for matters such as stadium financing,

infrastructure investments, and permits (Godfrey, 2009; Inoue et al., 2011). The influence

of political parties, particularly the Green Party in various Bundesliga cities (e.g.,

Freiburg), further underscores the importance of aligning CSR initiatives with

environmental expectations (Lucidarme et al., 2017). One of the most influential

governmental programs was the Green Goal program, an initiative launched in 2006 during

the FIFA World Cup in Germany (Kramer, 2006). The program, developed in collaboration

with governmental bodies and environmental organizations, aimed to project an eco-

friendly image of the country and left a legacy promoting sustainable practices in German

football.

Yet not just the German government influences CSR initiatives within the

Bundesliga politically. Football governing associations (FIFA, UEFA, DFB, and DFL)

also influence CSR within football in Germany. For instance, the DFL General Assembly

passed a resolution on a mandatory sustainability guideline in their licensing regulations

for all clubs in its 1. Bundesliga and 2. Bundesliga in May of 2022, making it the first major

professional soccer league to integrate such criteria (DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga, 2024b).

However, these associations do not usually impose binding obligations on the clubs, they

rather lead by example through numerous campaigns and projects. For example, UEFA

annually donates a €1 million charity check, emphasizing anti-discrimination efforts in

partnership with Football Against Racism in Europe (FARE) (Schwery et al., 2011). At the

national level, the DFL founded the Bundesliga Foundation, focusing on national-level

projects related to children, disabled individuals’ access to matches, integration, violence

prevention, and supporting athletes from less spotlighted sports (DFL Deutsche Fußball

14

Liga, 2024a). Moreover, the 50+1 rule, enforced by the German Football Association

(DFB) and the Deutsche Fußball Liga (DFL), stands as a distinctive and pivotal principle

within German football governance (Eilers, 2014). The principle ensures that clubs

maintain a majority stake (at least 51%) of their voting rights within their membership

structure (Deutscher Bundestag, 2022; DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga, 2023b).

While the DFB and DFL enforce the role, the German government also plays a

distinct role in its enforcement and scrutiny. The “Bundeskartellamt,” Germany's

independent competition regulator, has been actively involved in assessing the compliance

of the 50+1 rule with German competition law, especially in recent years

(Bundeskartellamt, 2024). In its preliminary assessment in 2021, the “Bundeskartellamt”

concluded that while the rule may restrict competition, it serves legitimate objectives,

particularly in maintaining the participatory and “member-led nature” of German football

clubs (Ford, 2021). The assessment came in response to recent attempts that challenged the

legality of the 50+1 rule. Critics argued that the rule breaches competition law because it

hinders investment opportunities in German football (Ford, 2021). Ultimately, the

“Bundeskartellamt” provided legal backing to the rule, especially acknowledging its role

in ensuring fairness and preserving the unique characteristics of German football clubs

(Bundeskartellamt, 2024). As such, the regulation sets Germany apart internationally.

Unlike many other football leagues globally, where ownership by external investors or

corporations is common, the 50+1 rule prioritizes fan involvement and community

influence, preserving the club’s control against corporate takeovers (Deutscher Bundestag,

2022). This approach underscores Germany’s distinct political landscape while

emphasizing a fan-centric model that explains the very common, deeply rooted regional

connection of the clubs with their communities (Breitbarth et al., 2011; Gehrmann, 1999;

Hamm, 1998).

RB Leipzig and TSG Hoffenheim are two exempt cases to the 50+1 rule in the

Bundesliga. Their exemptions are only allowed due to substantial external investment, RB

Leipzig with Red Bull’s sponsorship and TSG Hoffenheim through benefactor Dietmar

Hopp (Lammert, 2008; Lammert, 2014). Moreover, Bayer 04 Leverkusen and Vfl

Wolfsburg pose as additional distinctive cases due to a unique provision in the 50+1 rule,

15

allowing exemptions for investors with a longstanding interest exceeding 20 years in a club

(DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga, 2023b). The official Bundesliga website (2023) explains how

the club was established by employees of the German pharmaceutical company Bayer and

has, since its foundation in 1904, always maintained a connection with its corporate origin.

In parallel, Vfl Wolfsburg, established in 1945, is affiliated with the local Autoworks due

to the nature of the city’s creation being to accommodate Volkswagen workers. Both clubs

have been under the ownership of their respective companies since their inception,

predating their entry into the Bundesliga, therefore exempting them from the 50+1 rule

(DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga, 2023b).

While these exceptions have brought financial stability and success to these clubs,

they have brought mixed reactions among fans. Some appreciate the benefits these

investments bring, while others perceive these clubs as straying from the traditional

ownership model (Bauers et al., 2019; Inoue et al., 2011). Additionally, the

“Bundeskartellamt” raised concerns about current exemptions because they seemingly

undermine the rule's core principles of membership participation and fairness (Ford, 2021).

The resulting tensions sparked an ongoing debate within the football community regarding

the balance between financial stability and maintaining the essence of fan influence in club

matters (Bauers et al., 2019) – potentially affecting these clubs’ CSR strategies. As such,

the analysis of CSR activities, especially on the individual level of each club within the

Bundesliga, provides an interesting setting to study CSR further.

Theoretical Background

Understanding the theoretical foundations is pivotal in learning about the CSR

standards within the Bundesliga clubs. Porter and Kramer (2011) described how corporate

businesses must explore the principle of “shared value” to increase performance, improve

financially, and enhance brand reputation. As previously described, sport organizations

mirror such corporations in their financial operations, strategic planning, marketing

objectives, personnel management, operational efficiency, and stakeholder engagement –

so, to thrive clubs in the Bundesliga must navigate and implement similar theoretical

dimensions and approaches (Inoue et al., 2011). Especially, the dynamics among the

16

diverse stakeholder groups uncover a spectrum of opportunities and challenges vital for

sustainable growth (Walters & Tacon, 2010). In the context of the Bundesliga, all of the

clubs have to acknowledge societal interests and generate value through CSR initiatives,

not only for the clubs’ shareholders but also for the public (Figure 2.1; Porter & Kramer,

2011). This aligns with Carroll and Buchholtz’s (2014) concept of “stakeholder symbiosis”

depicted in Figure 2.2. To be successful, clubs must comprehensively examine the

challenges faced by each stakeholder group while recognizing the persistent

interdependence. For instance, while fans and local communities might not explicitly

articulate their needs, neglecting their concerns can profoundly impact the club's societal

standing and economic health (Walker & Kent, 2009). Both perspectives illustrate the

intrinsic link between a club’s sporting success and its stakeholder engagement,

underlining the significance of aligning club objectives with the interests of fans,

communities, and broader societal needs (Breitbarth et al., 2011). To ensure a

comprehensive examination of the CSR standards present within each club of the

Bundesliga, as well as the reasons behind potential differences, multiple theories, CSR

frameworks, financial components, and consumer responses – dimensions that possibly

influence stakeholder value – have to be considered.

Prominent Theories

To comprehend specific progress and define standards, key CSR theories must be explored.

CSR has shifted from philanthropy to stakeholder engagement, aligning increasingly with

Corporate Governance (CG) (Kumar, 2012). Both concepts are driven by ethical norms

and accountability, emphasizing how organizations interact with stakeholders, the

environment, and society—with both concepts focusing on transparency, sustainability,

and ethics (Jo & Harjoto, 2011). Corporate governance theories are therefore valuable in

understanding CSR responsibilities and activity levels. The five most prominent theories

are listed below.

17

Figure 2.1. Non-hierarchical stakeholder map of a German Football club

(Source: adapted from Breitbarth, 2012)

Figure 2.2. The Stakeholder Symbiosis

(Source: adapted from Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014)

Business'

success

Stakeholders'

success

FIFA

UEFA

Bundesliga

Government

European

Clubs

Public

International

Regularly Bodies

& Influence

Club

DFL

& DFB

Broadcasters

& Media

Employees

Own Business

Sponsors

Community

Players

& Agencies

Review

Bodies

Club

members

Fans

(Consumers)

Commercial

Partners

18

The Agency Theory

The agency theory explores the separation of ownership in firms and resulting

principal-agent problems while identifying the board of directors as a monitoring

mechanism to mitigate these issues (Mallin, 2016). Furthermore, the theory categorizes

managers as “agents” and owners as “principals”, suggesting that their self-interest drives

their decision-making. The theory focuses on contractual relationships within the firm,

investors’ knowledge, and the alignment of those with corporate governance activities

(Daily et al., 2003). Despite aiming to maximize shareholder value, the theory highlights

the risk of managers acting independently due to ownership separation. The efficacy of the

theory lies in diverse ownership structures within specific countries (Jensen & Meckling,

1976).

The Stakeholder Theory

The stakeholder theory centers around identifying and defining various

stakeholders within an institution, emphasizing the need to balance diverse needs for

organizational success (Wan Yusoff & Alhaji, 2012). In contrast to the agency theory, it

broadens the view beyond shareholders, recognizing governmental bodies, societies,

communities, employees, and the environment as critical components (Coleman et al.,

2008; McDonald & Puxty, 1979). This approach has gained prominence due to evolving

business models and heightened expectations for transparency and accountability in all

industries (Wan Yusoff & Alhaji, 2012). Based on the theory, Rodrigues et al. (2002)

categorized stakeholders into three types: (a) consubstantial, (b) contractual, and (c)

contextual stakeholders. He therefore highlighted individuals’ significance in creating

business credibility and brand reputation within social and environmental contexts

(Rodriguez et al., 2002).

The Resource Dependency Theory

The resource dependency theory asserts that a firm’s success hinges on its

connections with external resources, advocating for management to integrate with external

factors for future success (Hillman et al., 2000). The theory explores the role of directors

19

in incorporating uncertain environmental elements and emphasizing the interdependence

between organizations for necessary resources (Pfeffer, 1972). Ultimately, it suggests the

involvement of directors on multiple boards to bring essential elements like suppliers and

buyers into the corporation (Eccles & Williamson, 1987).

The Stewardship Theory

The stewardship theory presents managers as “good stewards” expecting them to

prioritize the corporation’s best interests (Donaldson & Davis, 1991). The theory is

grounded in social psychology analysis, it views the steward as a collectivist who balances

tensions among stakeholders to maximize shareholder value by maximizing a firm’s

performance (Smallman, 2004). The theory underscores a direct link between managerial

actions and firm success, advocating for a simplified, empowered organization where a

single person assumes responsibility for corporate vision and strategy (Davis et al., 1997).

Unlike the resource dependency theory, it doesn't advocate for a separation between the

roles of chairman and CEO (Clarke, 2004).

The Social Contract Theory

Unlike the other theories, the social contract theory categorizes society into

distinct social contracts between the society itself and its members (Allen, 1999).

Individuals voluntarily come together to form such a society and establish a governing

structured based on mutual agreement. Social responsibility is seen as an obligation of

organizations to society, presenting an integrated theory with macrosocial and microsocial

contracts guiding ethical decision-making (Donaldson & Davis, 1991).

While each theory gives a particular perspective on CSR, the stakeholder theory

served as the foundation for further analysis. The underlying model of the stakeholder

theory, in contrast to the other theories, is not a single approach focusing on a company’s

objectives, it contemplates a variety of influential factors such as a social, economic,

political, and ethical dimension (Coleman et al., 2008; McDonald & Puxty, 1979; Wan

Yusoff & Alhaji, 2012). Furthermore, the theory stood out as the optimal model,

specifically for the sport and soccer context due to the unique interplay between sport

20

organizations and society (Coskun et al., 2020; Walker and Kent, 2009) and the necessity

to therefore include multiple dimensions (Painter et al., 2021; Rodriguez et al., 2002). In

an industry where sport teams and organizations are deeply rooted in their regional

communities, the stakeholder theory proved most diverse in understanding all viewpoints

(Breitbarth et al., 2011; Gehrmann, 1999; Hamm, 1998). It acknowledges the intricate

relationships between entities and considers the broader impact of organizations, beyond

mere corporate goals. Thus, making it a more fitting model for understanding the levels of

CSR within each club within the Bundesliga.

Conceptualization of a sport-based CSR framework

Due to the unique nature of the sport setting, Carroll’s (1979) theoretical

frameworks and models assisted in removing inconsistencies and allowed for an analogy

to be drawn between each club. This enabled further comparison of the clubs. Carroll’s

three-dimensional pyramid from 1979 and the following adaptations (Carroll & Buchholtz,

2014), as well as Visser’s (2006) version, were used to establish a sport-based CSR

framework (Figure 2.3). The model allowed an examination and contrast of the differences

in CSR standards within the Bundesliga clubs and was adapted due to the unique drivers

of CSR within the Bundesliga (societal, economic, and political). By stating that the

“economic” and “legal” layers are required by society – and by the clubs to ensure financial

survival – the assumption is made that these layers are identical within each of the clubs.

However, based on the notion of regional differences and the varying historical foundations

of the clubs, a new layer of “societal and regional responsibilities,” seen as expected, was

added. This reflects the unique nature of sport organizations in comparison to regular

businesses, due to the intense emotional connections with fans, their interconnectedness

with the community, and diverse stakeholder dynamics (Coskun et al., 2020).

The framework ultimately establishes the responsibilities that the clubs have

towards each of their stakeholder groups. These lie within the levels of economic, legal

and political, ethical, societal and regional, and philanthropic obligations. To ensure a

multi-dimensional analysis, Carroll and Buchholtz’s (2014) Stakeholder Management

Capability (SMC) scale served as an evaluation framework (Figure 2.4). The information

21

on the scale aids in identifying how much each club recognizes and emphasizes the

relationship with its stakeholders. While clubs on the rational level are identified as simply

acknowledging the existence of stakeholders, clubs on the process level have started

incorporating stakeholder needs. The transactional level within the scale implies that a club

has reached a certain standard of authentic engagement resulting in a purposeful

relationship. The scale therefore enables an analysis of the level of CSR activities and

differing standards within each club in the Bundesliga.

Classification of CSR focus areas

When measuring the CSR activities, a distinction must be made that divides each

initiative into a theme/ focus area. This subdivide results in the identification of the CSR

area in which each club is most involved. The themes have been established on the

foundation of the internationalized ISO standards (ISO 26 000 themes, 2010; Appendix J)

and adjusted based on the identified societal, economic, and political drivers behind CSR

in the German Bundesliga.

The following themes served as classification:

(1) Regionally-focused Involvement

(2) Education and Health Promotion

(3) Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI)

(4) Integration, Tolerance, and Racism (role model identification)

(5) Environment and Sustainability (stadium management, climate protection, etc.)

(6) Internal Child and Youth Development

(7) Fair Operating and Business Practices (corruption prevention, working conditions,

etc.)

(8) International Involvement (e.g., in FIFA initiatives)

22

Figure 2.2. Conceptualization of a sport-based CSR Framework

(Source: adapted from Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014 and Visser, 2006)

Definitions

Level of SMC

Transactional

Engagement in authentic, purposeful

relationships with stakeholders.

Process

Establishment and incorporation of

practices to track actions for stakeholder

satisfaction.

Rational

Acknowledgement of stakeholder

existence and their legitimate stakes in a

business.

Figure 2.4. Stakeholder Management Capability Scale (SMC)

(Source: adapted from Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014)

Philanthropic

Responsibilities

= be proactive

Societal and Regional

Responsibilities

= be engaged in the

community

Ethical Responsibilities

= be ethical, be transparent, be fair

Legal and Political Responsibilities

= obey the law

Economic Responsibilities

= be profitable, be accountable

Expected

Required

Required

Desired

3 – Transactional Level

2 – Process Level

1 – Rational Level

Expected

23

Financial Performance

In an international business context, studies have explored the relationship between

financial performance and CSR, especially among multinational corporations (Awaysheh

et al., 2020). Such research suggests that larger corporations, which often face greater

media scrutiny and emphasize brand reputation, tend to experience higher profits, and are

better equipped to invest in CSR initiatives (Park et al., 2014). Translating this insight to

the Bundesliga, exploring the financial background of each club becomes crucial in

understanding the current CSR standards within each club (Inoue et al., 2011). A club's

financial stability directly impacts its ability to invest in CSR initiatives, dictating the

resources available for sustainable practices and community engagement (Awaysheh et al.,

2020; Inoue et al., 2011).

The balance sheet total was utilized for assessing the financial standing of the clubs

within the Bundesliga. This metric offers a comprehensive view of the clubs' financial

resources, including cash and equity, investments, property, equipment, assets, and

liabilities – therefore depicting a club’s capacity for sustained investment in CSR activities,

to repay debts, and to distribute profits to shareholders (Wilson, 2011). This gives insights

into the club's resources, including cash, investments, property, and equipment, which can

depict its capacity for sustained investment in CSR activities (Wilson, 2011). It is the most

accessible option to capture the full financial strength and asset availability of each club

for CSR initiatives. Ultimately, the decision to use this metric stemmed from its

significance in depicting long-term financial strength and its accessibility through the

independently published financial information by the DFL for each club in the Bundesliga

for the respective fiscal year.

Consumer Social Response (CnSR)

Consumer Social Response (CnSR) within the German Bundesliga context refers

to how fans and stakeholders react to a club's involvement in social causes, environmental

care, welfare, and ethical management. Initiatives pursued by clubs are, therefore,

reflective of their fans' behaviors (Brown & Dacin, 1997). A fan’s buying habits regarding

tickets, merchandise, and other products are linked directly to their perspective on how

24

responsible a company is concerning the five dimensions (economic, legal and political,

ethical, societal and regional, and philanthropical (Ramasamy & Yeung, 2008). Marquina

Feldman and Vasquez-Parraga (2013) argued that companies invest greater resources into

CSR practices once they perceive a positive correlation between their CSR initiatives and

CnSR. Moreover, Contini et al. (2020) examined how CSR activities can increase an

organization’s sales while fostering consumer loyalty – consequently, improving their

brand reputation. This heightened awareness and positive consumer attitude fortifies the

club against negative perceptions and may even foster new partnerships and sponsorships

in the future (Bhattacharya & Sen, 2004). Due to the lack of availability of merchandise

sales figures of the clubs, the analysis had to utilize a different approach to achieve a

quantifiable, measurable report. Therefore, three indices were selected to evaluate the

reactions of various stakeholders for the 2021-2022 season: (a) sponsor investments, (b)

the average attendance in relation to stadium capacity, and (c) a ranking of the clubs’

national popularity. The information about sponsors and their investments was gathered

through a study by ISPO Messe München (ISPO Sports Business Netzwerk, 2023b). This

information was crucial to understand the financial backing and support each club received

from sponsors during the 2021-2022 season. Furthermore, the Information gathered from

Transfermarkt indicates the average percentage of stadium capacity that was reached by

each club throughout the season, reflecting fan engagement and attendance trends

(Transfermarkt, 2023). Lastly, the ranks of the national popularity report by SLC

Management (2022) were utilized to further the analysis and gain an additional, more

extensive perspective. Their study evaluates the clubs yearly through a variety of criteria

to determine the popularity of Bundesliga clubs. It encompasses objective measures like

fan clubs, social media presence, and memberships, as well as subjective factors such as

the atmosphere in their stadium, general vs. league popularity, customer satisfaction, and

family friendliness (SLC Management, 2022). Consequently, being more comprehensive

and therefore, valuable when wanting to compare the individual levels of CSR standards

within the clubs.

25

Research Questions

Even though the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility has a long history and

has become increasingly significant within business and philanthropic leadership, the idea

has only reached the sport industry in the last decade (Reuter & Thalmeier, 2023). CSR

within sports plays a different role than in other industries (Painter et al., 2021). Sport

organizations are not solely just businesses but are intertwined within society and the

community they are established in – ultimately leading to a new setting in which CSR must

be analyzed (Coskun et al., 2020). Football in Europe has started to embrace the concept,

leading to a substantial surge in CSR programs within sport teams and establishing a new

perspective and foundation for CSR in the football industry (Reiche, 2013). Germany, one

of the leading football markets with one of the most successful sports leagues in the world,

is also working to impact society. Therefore, this study addresses the following research

questions:

1) What are the CSR standards of the clubs of the 1. Bundesliga in the 2021–2022

season?

2) What are the differences in CSR focus areas and standards of those clubs?

26

CHAPTER THREE – METHODOLOGY

Sample Size

The study includes 16 teams/ clubs of the 1. German Men Bundesliga (Table 3.1)

and their respective foundations, if one had been established (Table 3.2). These represent

the best nationwide clubs in Germany in the 2021 to 2022 season and are distributed across

the country. Excluding the two relegated clubs (Arminia Bielefeld, Spvgg Greuther Fürth)

from the season was based on the assumption that these clubs might face imminent

challenges, potentially leading to reduced investment or prioritization of CSR initiatives.

Furthermore, the decision to exclude these clubs was reinforced by practical

considerations regarding the availability of CSR reports. Not all clubs had annually

published CSR reports accessible for the 2021–2022 season, so reports relating to the

2022–2023 had to be included for some clubs. This maintains consistency and ensures the

analysis' integrity by focusing on clubs with a continued presence within the league over

both seasons, providing a more accurate portrayal of CSR efforts within the context of the

1. Bundesliga. These 16 clubs are listed in Table 3.1 (Olympia-Verlag, 2023).

For analytical purposes whichever independently published annual CSR report was

available was used, however as mentioned, this varied between the 2021–2022 and 2022–

2023 season. Detailed information from these reports or the respective websites can be

found in Appendices B through I. The first German football league was purposefully

chosen to ensure that the sample size varied in location, club size, ownership, and

organizational structure so that the analysis was as broad as possible. The decision to solely

include the men’s first league was based on the greater availability of data and media

coverage due to the league’s enormous popularity and success. The teams’ importance is

reflected by their immense national fanbases as well as international prominence. The

information on the club’s establishment of foundations was used to gain insights into the

corporate structures of the clubs and consequently, how each club organized, supervised,

and emphasized CSR importance (Reiche, 2013).

27

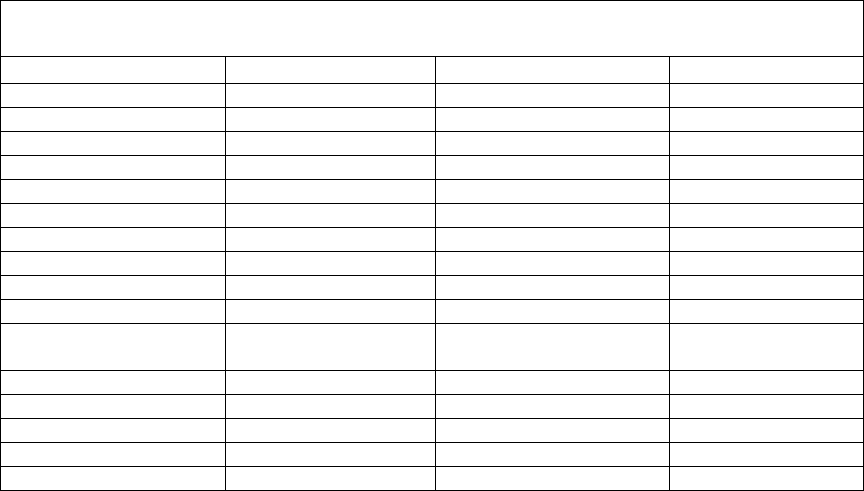

Table 3.1. The clubs of the 2021-2022 season of the 1. German Bundesliga

Clubs of the 2021 -2022 Men’s Bundesliga season

FC Augsburg

Hertha BSC

1. FC Union Berlin

RB Leipzig

Vfl Bochum

Bayer 04 Leverkusen

Borussia Dortmund

1. FSV Mainz 05

Eintracht Frankfurt

Borussia Mönchengladbach

SC Freiburg

FC Bayern München

TSG Hoffenheim

VfB Stuttgart

1. FC Köln

Vfl Wolfsburg

FC Augsburg

Hertha BSC

(Source; Olympia-Verlag, 2023)

28

Table 3.2. The respective foundations of the clubs

Bundesliga Club

Foundation

FC Augsburg

N/A

Hertha BSC

Hertha BSC Stiftung

1. FC Union Berlin

1. FC Union Berlin e. V. „UNION VEREINT."

Vfl Bochum

Vfl Bochum 1848 „HIER, WO DAS HERZ NOCH

ZÄHLT“

Borussia Dortmund

BVB-Stiftung

Eintracht Frankfurt

n.A.

SC Freiburg

Achim-Stocker-Stiftung

TSG Hoffenheim

TSG ResearchLab

1. FC Köln

Stiftung 1. FC Köln

Vfl Wolfsburg

Krzysztof Nowak-Stiftung

RB Leipzig

n.A.

Bayer 04 Leverkusen

Bayer 04-Sportförderung GmbH

(subsidiary enterprise)

Borussia Mönchengladbach

Borussia Stiftung

FC Bayern München

FC Bayern Hilfe e.V.

VfB Stuttgart

VfB-Stiftung Brustring der Herzen

1. FSV Mainz 05

N/A

(Source; DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga, 2010; Reiche, 2013)

29

Due to the variety of CSR-implementing infrastructures within the clubs of the

Bundesliga (e.g., foundations, subsidiaries), each respective approach had to be identified

and included to ensure a multidimensional, comprehensive examination of CSR-related

activities of each club – even those executed by external/ subordinate branches that act

within the scope of the official brand of each club.

Data Collection

Data were collected from 16 clubs in the German Bundesliga and their respective

foundations or departments (Table 3.1; Table 3.2). Either their publicly available CSR

reports or specifically published websites of each club were compiled (Appendices B

through I), utilizing document analysis and content analysis as a foundation for the division

of existing CSR areas in each report. Document analysis, primarily applied in qualitative

case studies, relies on non-technical literature like reports and internal correspondence for

empirical data. It plays a crucial role in uncovering insights and understanding complex

research problems (Bowen, 2009). The document analysis helped in gaining exclusive data

insights into each club's specific CSR activities. Based on the content analysis, the existing

CSR areas were summed up under the previously mentioned categorizations (regional-

focused involvement, education, and health promotion, DEI, integration, tolerance, anti-

discrimination, and racism, environment and sustainability, internal child and youth

development, fair operating and business practices, international involvement) for

simplification reasons and ensured ease of comparison.

The analyses were conducted by: 1. examining which content to use, 2. scanning

the content, 3. detailed examination of the content, and ultimately 4. interpreting the

findings (Bowen, 2009). The data collection was conducted between September 1, 2023,

and December 31, 2023. The timeframe was chosen to ensure an exhaustive search. While

document analysis stands as a valuable standalone method, it also complements other

research techniques (Bowen, 2009). This is why additional secondary data about CSR was

gathered such as external reports, financial reports, and information from governing

football associations. This includes a league-wide document from the DFL Deutsche

Fußball Liga GmbH. The document reports and summarizes the sustainability measures of

30

all clubs in the Bundesliga, and it is based on the individual, publicly accessible web pages

of each club as well as their own internal investigations (Göbl et al., 2013). The information

from the web pages includes breaking news, information about the team’s management

and updates, analysis of game results, and sharing planned activities concerning

community engagement. Moreover, the DFL portal “BundesligaWIRKT” served as the

main collection point for CSR reports with a total of 9 clubs making their reports available

for download on the (DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga, 2024c). Additionally, a report conducted

by Deloitte in 2019 about the sustainability within the Bundesliga was utilized. Deloitte’s

report entails the economic value creation, the social responsibility “of today and

tomorrow,” and the future perspective of sustainability in the Bundesliga (Ludwig &

Fundel, 2019). This iterative approach combines elements from content analysis and

thematic analysis. Such triangulation of data is employed to enhance the credibility of the

individual reports by cross-verifying findings from various sources and hence, establishing

a well-rounded overview and perspective (Bowen, 2009). Since some CSR reports are

published individually by the clubs, this step is essential when wanting to recognize

potential biases inherent in the information.

31

CHAPTER FOUR – RESULTS

Frameworks

The results are based on the findings of Deloitte’s sustainability report of the

Bundesliga and indicate that about 67 percent of the clubs manage their sustainability

measures by independent CSR departments (Ludwig & Fundel, 2019). Of this percentage,

40 percent also work with their foundation, which supports the implementation of

sustainability. Interestingly, none of the clubs in the report by Deloitte’s Sports Business

and Sustainability Group (2019) organized their sustainability activities exclusively

through either their own CSR department or a foundation (Ludwig & Fundel, 2019). At the

time that the report was conducted, a fifth of the clubs had not yet established structures

that specifically serve to address the topic (Ludwig & Fundel, 2019) – possibly, explaining

the lack of CSR-related publications by some of the clubs.

While the management structures and individual CSR publications done by the

clubs serve multiple stakeholders beyond just society or shareholders, the independently

published reports often serve to enhance their brand image (Ludwig, 2022; Lucidarme et

al., 2017). Additionally, the clubs utilize them to adhere to society’s expectations of

accountability and transparency (Wan Yusoff & Alhaji, 2012). Nevertheless, some clubs

implement CSR activities without full public disclosure. Although such reports are now

mandatory for the DFL licensing process, only nine of the 16 considered clubs have a

corresponding report available for download on the portal “BundesligaWIRKT” from the

DFL (as of 04.01.24). These clubs were Borussia Dortmund, Borussia Mönchengladbach,

FC Augsburg, Hertha BSC, RB Leipzig, Vfl Bochum, Vfl Wolfsburg, SC Freiburg and 1.

FSV Mainz 05 (DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga, 2024c). However, the only available report

for Mainz 05 in the portal was from 2020 while newer reports were available on their

website. Similarly, Bayer 04 Leverkusen also only made its report available for download

on their website. In addition to being the collection point for such reports, the DFL portal

also showcases other ongoing social and community engagement activities (DFL Deutsche

Fußball Liga, 2024).

32

Classification of CSR focus areas

The projects, initiatives, programs, and other similar activities within each club’s

report are categorized across the eight classifications. Each of the focus areas is

overlapping to some extent. For analytical clarity, projects are allocated based on their

primary focus, ensuring each project falls into the category that best represents its core. For

instance, a weight loss project solely targeting regional participants would be categorized

under regional involvement instead of education and health promotion. Emphasizing

inclusivity, each project appears only once, ensuring a comprehensive yet streamlined

representation across the previously defined classifications: (1) Regionally-focused

Involvement, (2) Education and Health Promotion, (3) Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

(DEI), (4) Historical Responsibility, Tolerance, and Racism (role model identification), (5)

Environment and Sustainability (stadium management, climate protection, CO2

emissions), (6) Internal Child and Youth Development, (7), Fair Operating and Business

Practices (corruption prevention, human rights, working conditions), (8) International