Land Covenants in Auckland and

Their Effect on Urban Development

Craig Fredrickson

July 2018

Technical Report 2018/013

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on

urban development

Technical Report 2018/013 July 2018

Craig Fredrickson

Research and Evaluation

Auckland Council

Technical Report 2018/013

ISSN 2230-4525 (Print)

ISSN 2230-4533 (Online)

ISBN 978-1-98-856458-6 (Print)

ISBN 978-1-98-856459-3 (PDF)

This report has been peer reviewed by the Peer Review Panel.

Review completed on 11 July 2018

Reviewed by two reviewers

Approved for Auckland Council publication by:

Name: Eva McLaren

Position: Acting Manager, Research and Evaluation (RIMU)

Name: Regan Solomon

Position: Manager, Land Use, Infrastructure Research and Evaluation

Date: 11 July 2018

Recommended citation

Fredrickson, Craig (2018). Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on

urban development. Auckland Council technical report, TR2018/013

© 2018 Auckland Council

This publication is provided strictly subject to Auckland Council’s copyright and other intellectual property rights (if any) in the

publication. Users of the publication may only access, reproduce and use the publication, in a secure digital medium or hard copy, for

responsible genuine non-commercial purposes relating to personal, public service or educational purposes, provided that the publication

is only ever accurately reproduced and proper attribution of its source, publication date and authorship is attached to any use or

reproduction. This publication must not be used in any way for any commercial purpose without the prior written consent of Auckland

Council.

Auckland Council does not give any warranty whatsoever, including without limitation, as to the availability, accuracy, completeness,

currency or reliability of the information or data (including third party data) made available via the publication and expressly disclaim (to

the maximum extent permitted in law) all liability for any damage or loss resulting from your use of, or reliance on the publication or the

information and data provided via the publication. The publication, information, and data contained within it are provided on an "as is"

basis.

© 2018 Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities National Science Challenge

Acknowledgements

This research was conceived of by

Dr K. Saville-Smith as part of the Architecture of

Decision-making Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities programme, funded by the

Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities National Science Challenge and developed

and executed by Craig Fredrickson, RIMU, Auckland Council.

Executive summary

A covenant is a contract or promise between parties that binds them to obligations in a

contract for a fixed period of time, or in perpetuity. Covenants ‘run with the land’, meaning

they bind owners of the land to a covenant’s condition. In recent decades they have

become a common method for developers to control how future owners of land develop

and maintain land in New Zealand (Quality Planning, 2013; New Zealand Productivity

Commission, 2015). As such, covenants create a private planning regime that is

enforceable in the civil courts (Mead & Ryan, 2012; Toomey, 2017).

Strong population growth in Auckland is expected to remain high in coming years, putting

pressure on housing supply in the region. Council’s high-level strategy, The Auckland

Plan, and the Auckland Unitary Plan seek to use both urban intensification and expansion

to supply new dwellings to accommodate the increasing population. But will property level

constraints such as land covenants affect the city’s ability to grow as and where is

needed?

Land covenants in New Zealand are commonly used in modern residential subdivisions,

which are the focus of this research. They are used as a mechanism to control land use

and development, and to create and maintain neighbourhood amenity. There has been

little research on land covenants on residential land in New Zealand, and this report seeks

to understand their numbers, location, and nature in Auckland. The effects of land

covenants include acting as a barrier to development and redevelopment, increasing

house prices and decreasing affordability, and being used to stifle competition, as a

method of social exclusion, and as a form of land control. While covenants present a

number of disbenefits to some parties, they create benefits to others, including increased

property value, and maintained or increased amenity. Land covenants are also used to

protect heritage, and for conservation purposes.

Land covenants are spread across the Auckland region, where there are 151,170 land

covenants on 96,261 titles. The land area of titles with a covenant covers 60,757 hectares

or 12 per cent of Auckland’s land area. Residential zones contain 83,068 titles that are

affected by land covenants, or 19 per cent of the total number of titles in residential zones;

these titles cover an area of 8685 hectares, 23 per cent of the total area of residential

zones. Residential zoned titles with land covenants are concentrated in greenfield suburbs

that have been developed over the last few decades. Analysis shows the proportion of

titles with land covenants in residential zones has been increasing over time. Less than 10

per cent of titles issued in the early 1980s in current residential zones had a land covenant

on them; for titles issued in 2017 it is over 50 per cent. Furthermore, over three-quarters

(86 per cent) of the covenants in residential zones are on titles that have been created in

the last 30 years. Properties in residential zones with a land covenant have commercially

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development i

feasible capacity for 13,243 additional dwellings, or 12 per cent of the total commercially

feasible capacity for all residential zones.

Centre zones contain 2529 titles affected by covenants; they cover a land area of 336

hectares, or 23 per cent of the total combined area of centre zones. In the Future Urban

zone, 897 titles have covenants or 26 per cent of the total titles in the zone. The land area

of the titles with covenants in this zone is 10,674 hectares, or 26 per cent of the total land

area of the zone. Over 5800 titles in rural zones have a land covenant or 19 per cent of the

total tiles in these zones. The Countryside Living zone has the highest number (2507) and

the highest proportion (34 per cent) of titles with land covenants of any of the rural zones.

Analysis of the data by local board area shows that Howick Local Board has the largest

number of titles with land covenants (18,261). Other local boards with high numbers are

Hibiscus and Bays (11,746) and Upper Harbour (11,414). Upper Harbour Local Board has

the highest proportion of titles with covenants with 46 per cent. Auckland’s two rural local

boards, Rodney and Franklin, each have just under 9000 titles with covenants, accounting

for 29 per cent and 28 per cent of the total number of titles in each respectively.

Covenants present a number of barriers to development and redevelopment in an urban

context. In Auckland the presence of covenants in residential areas earmarked for

intensification, or future urban expansion, will have an effect on the ability of these areas to

change. While land covenants will have an effect on urban development in the future, they

can also have a number of benefits such as providing assurance to prospective buyers on

the quality of development and neighbourhood amenity. Covenants may be a barrier to

urban development, but there are also a number of solutions that could be employed to

overcome them. These include the use of time limits or sunset clauses on new covenants,

the introduction of an easy process for those with benefits from covenants to agree to have

them modified or removed, and legislative change to allow for public planning documents

to override covenants – as is done in New South Wales.

The contents and effects of land covenants are difficult to understand, given the way

information about them is stored by Land Information New Zealand, and further research

on the topic may be required to fully comprehend their present and future impacts.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development ii

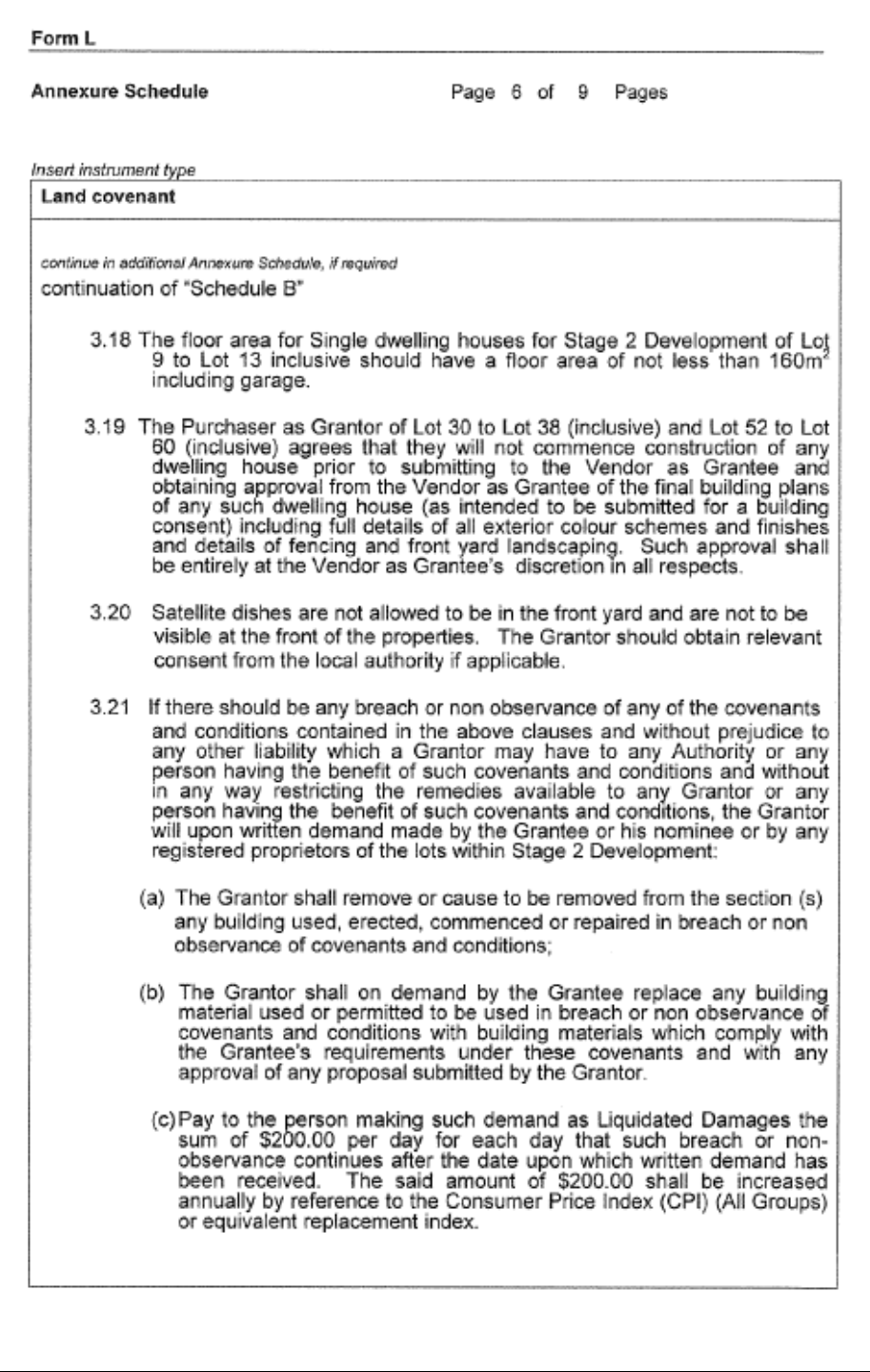

Figure: Titles with land covenants in Auckland

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development iii

Table of contents

Executive summary .............................................................................................................. i

Table of contents ................................................................................................................ iv

1.0 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1

1.1 Scope of this report ............................................................................................ 2

2.0 Background ................................................................................................................. 3

2.1 What is a land covenant? ................................................................................... 3

2.2 Use of land covenants in New Zealand .............................................................. 5

2.3 Land covenants in overseas jurisdictions ......................................................... 10

2.4 The effects of land covenants .......................................................................... 12

3.0 Method to identify titles with land covenants in Auckland .......................................... 18

3.1 Caveats, limitations, and notes on outputs ...................................................... 19

4.0 Analysis ..................................................................................................................... 21

4.1 Land covenants by local board ........................................................................ 22

4.2 Land covenants by zoning ............................................................................... 24

4.3 Plan enabled and feasible capacity of parcels with land covenants in residential

zones ......................................................................................................................... 30

5.0 Discussion ................................................................................................................. 34

6.0 Conclusion ................................................................................................................. 40

7.0 References ................................................................................................................ 42

8.0 Appendices ................................................................................................................ 48

Example of schedule of covenants for a residential subdivision .................. 49 Appendix A:

Number of titles, land covenants, and titles with land covenants in Auckland Appendix B:

2018, by Auckland Unitary Plan (operative in part) zone ................................................... 58

Area zoned and area covered by land covenants in Auckland 2018, by Appendix C:

Auckland Unitary Plan (operative in part) zone .................................................................. 60

National Policy Statement on Urban Development Capacity 2016: Housing Appendix D:

and business development capacity assessment for Auckland. Executive summary.

(Auckland Council, 2017) ................................................................................................... 62

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development iv

1.0 Introduction

Land covenants are a legal mechanism that can be used to control land, what it can

be used for, and can stipulate the types of development that can occur on it.

Covenants placed on land either restrict or require a land owner to do or not do

something, depending on the terms of the covenant deed. In New Zealand over the

last few decades, land covenants have become a popular way for developers to

control land use, building style, and other aspects of neighbourhoods, as a way to

increase or maintain perceived value (Mead & Ryan, 2012; Rikihana Smallman,

2017; Land Information New Zealand, n.d.). Land covenants have also been a

popular mechanism in New Zealand to protect for conservation land which is

privately owned, through the Queen Elizabeth the Second National Trust (QEII Trust)

(Saunders, 1996), through the Reserves Act 1977, or by consent notice under the

Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA).

Land covenants play an important but often hidden role in our planning system, with

their abundance and impacts little understood. In New Zealand there is little evidence

to understand how land covenants, and other barriers, slow down the delivery of

housing to the market (Johnson, Howden-Chapman, & Eaqub, 2018). Land

covenants in effect are private planning rules that are enforceable through civil courts

(Mead & Ryan, 2012), and at times do not match, or are counter to, both strategic

plans and the district planning rules.

Auckland has had strong population growth in the last decade, with it increasing by

180,700 people to a total of 1,657,200, between 2008 and 2017 (Statistics New

Zealand, 2017). The city’s population growth is also expected to remain strong into

the future, with the region projected to accommodate 60 per cent of the country’s

population growth to 2043 (Ross, 2015). Rather than keeping pace with population

growth, dwelling growth in the city has not been as strong, creating what is being

widely called a “dwelling shortfall” (New Zealand Government & Auckland Council,

2013; Alexander, 2015). In order to overcome the shortfall, and increase dwelling

growth, Auckland Council’s spatial plan (known as The Auckland Plan), set out a

development strategy that built on legacy regional planning approaches that were

based on the compact city model. The plan sought to accommodate 400,000 new

residential dwellings, or between 60-70 per cent of projected dwelling growth to 2040

in the existing urban area (as at 2012) (Auckland Council, 2012). A new updated

version of the spatial plan (still in draft form, and known as Auckland Plan 2050)

continues the strategy of both urban intensification and expansion (Auckland Council,

2018). Given the importance of both the intensification and the expansion of

Auckland’s urban area to increase dwelling numbers, will constraints at the individual

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 1

property level, such as land covenants, affect the city’s ability to grow as and where

is needed?

New planning rules enabled by the Auckland Unitary Plan came into effect over most

of the city in November 2016. The plan indicated that many areas that are currently

rural or semi-rural on the urban fringe, often typified by large lot residential and

countryside living will be the site of future urban development. In addition, more

permissive rules increasing dwelling densities across most of the suburban area

were also introduced; this will likely see dwelling intensification through infill

development, redevelopment, addition of minor household units (granny flats), and

internal subdivision of dwellings. But will the presence of land covenants that restrict

owners on what they can do with their properties affect the ability of the city to

develop as planned?

1.1 Scope of this report

The analysis undertaken and reported in this study explores the location and quantity

of property affected by land covenants across the entire Auckland region. The focus

of comment and discussion in this report is on how covenants may affect urban

development, redevelopment, expansion, and change, and understanding how the

possible future effects of covenants may impact on the city’s long-term growth

strategy and the planning rules.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 2

2.0 Background

2.1 What is a land covenant?

A covenant is a contract or promise between parties that bind them to obligations in a

contract for a fixed period of time, or in perpetuity. Covenants, or private deed

restrictions, have featured in England and Wales land and property law since the 16

th

century (Taylor & Rowley, 2017), but their modern origins began in England in 1848

with the case of Tulk v Moxhay (1848). Many of New Zealand’s laws are derived or

have evolved from statues enacted in the United Kingdom, including laws around

covenants. Covenants ‘run with the land’, meaning they bind owners of the land to a

covenant’s conditions, often in perpetuity. In recent decades they have become a

common method for developers to control how future owners of land develop and

maintain land in New Zealand (Quality Planning, 2013; New Zealand Productivity

Commission, 2015). As such, covenants create a private planning regime that is

enforceable in the civil courts (Mead & Ryan, 2012; Toomey, 2017).

In the context of this research, land covenants refer to those which affect freehold

land. Covenants relating to leases and leasehold land form a distinct area of land law

and as such are not addressed in this research.

Land covenants that require a land owner to do something are positive covenants,

and those that prohibit or prevent an owner from doing something are known as

restrictive covenants. In New Zealand, land covenants may be private agreements

between parties, or imposed by councils as conditions of the land use and

subdivision consenting process (Mead & Ryan, 2012; Quality Planning, 2013).

Official records of covenants and their details are documented against a title in Land

Information New Zealand’s (LINZ) computer register.

Land covenants between two or more parties have a grantor and a grantee (also

known as a covenanter). The grantor of the covenant (also called the covenanter)

agrees to have a burden on their land, to the benefit of another piece of land. The

grantee (also known as a covenantee) agrees that their land will have the benefit

associated with the covenant. Land that has the burden of a covenant is known as

the servient land, while land that has the benefit of the covenant is known as the

dominant land. Under the provisions of the Property Law Act 2007, land covenants

give the grantee a legal interest in the land (Property Law Act 2007, 2007).

Mutual land covenant schemes impose restrictions or control land use or building

styles, with the scheme allowing each lot to be both dominant and servient land for

the covenants in relation to all the other lots in the scheme (Land Information New

Zealand, n.d.). Mead and Ryan (2012) note that in New Zealand it is common for

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 3

large residential subdivisions to have a building scheme, which LINZ refers to as

‘mutual land covenant scheme’. Schemes place restrictions on the use of the land,

and aim to maintain the quality of the neighbourhood; any owner of land within the

scheme may enforce against another any of the covenants made under the scheme

(McMorland et al., 2017).

Covenants can also be applied on a property as a condition of resource consent

under the Resource Management Act 1991.

Covenants on land can be created through three mechanisms enabled by the Land

Transfer Act 1952

1

. Covenants are added to a piece of land’s Certificate of Title

through the creation of an easement instrument. Section 90 of the Act outlines that

this can be done in one of three ways (Land Transfer Act 1952, 1952). The first is

through a transfer instrument. This is when a covenant is created when the

ownership of land is transferred from one party to another. The second is through an

easement instrument. This is when a covenant is created and is registered on the

title using an easement instrument. Thirdly, covenants can be created through a

deposited plan. This is when a new property is created through a subdivision and the

plans are registered, with any covenants, and new Certificates of Title are issued.

Cross lease titles, the terms of their leases, and related covenants, are registered in

an easement instrument just like any other other covenant. While covenants relating

to cross leases are land covenants, due to their unique nature and complex issues

(Fredrickson, 2017) they have been excluded from analysis with other land

covenants in this research,

While land covenants can prevent land owners from undertaking certain activities,

they are not permitted, or can be voided, if they breach the provisions of legislation,

specifically the Human Rights Act 1993, the Residential Tenancies Act 1986, the

Property Law Act 2007, or the Commerce Act 1986 (Hinde, McMorland, & Sim,

2018).

Land covenants can be revoked or modified under Section 307 of the Property Law

Act 2007, and must be executed by the registered proprietors of the affected

dominant and servient titles (Land Information New Zealand, n.d.). The High Court

also has jurisdiction to modify or extinguish land covenants under Section 3017 of the

Act, when an application is made to the Court by someone bound or burdened by a

positive or restrictive covenant (Property Law Act 2007).

1

Aspects of the Act relating to the creation of easement instruments was amended by the Land

Transfer (Computer Registers and Electronic Lodgement) Amendment Act 2002

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 4

2.2 Use of land covenants in New Zealand

The most common uses for land covenants in New Zealand are those associated

with residential subdivisions, the focus of this research. Covenants are also used

protect heritage, and for conservation purposes. Covenants can also be used for

water and soil, forest research areas, and wahi tapu, all in respect of Crown forestry

licences, and for purposes under the Resource Management Act 1991 in connection

with resource consents and subdivisions (Hinde et al., 2018).

2.2.1 Residential subdivision

There is little academic literature on the use of the land covenants on residential land

in New Zealand, but there has been much coverage in local media on the subject in

recent years, and comment by the New Zealand Productivity Commission in their

report on using land for housing published in 2015. For Auckland there has been no

research on land covenants to date. Hattam and Raven (2011) undertook research

on the extent of the use of land use covenants in the Rolleston area in Canterbury,

and found that 75 per cent of new residential properties had a restrictive covenant

requiring a minimum dwelling size of at least 160 square metres, with 180 square

metres being a typical requirement. Also observed was that only three per cent of the

properties in the area created in Rolleston since 1990 had no covenants specifying

the minimum size of dwellings that could be built (Hattam & Raven, 2011).

Examples of the restrictions used in covenants in new residential subdivisions

include subdivision controls, stipulations on the size of dwellings, their form, and their

construction material, and directions on landscaping and fencing. The following part

of this report presents a synthesis of restrictions observed, from a variety of sources,

including (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2015), reports in online media (for

example, Dally, 2013; Simpson, 2016; Rikihana Smallman, 2017), analysis supplied

by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (S. Jacobs, personal

communication, March 1, 2018), developer/ development websites (for example,

Addison, 2010; Beach Grove, 2013; Silverwood Corporation, 2014), and from

personal inspection of covenant schedules on Certificates of Title. While this

summary is not extensive, it provides some insight into the types of restriction that

have been used.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 5

Subdivision and land use

• No further subdivision allowed, or no further subdivision without the consent of

the developer.

• Developer approval of house plans required before construction (although one

case cited noted that this clause expired a few years after the subdivision went

on sale).

• No commercial activity in residential properties.

• No state housing is allowed.

Dwellings and construction

• Minimum floor area of the dwelling; some include the floor area of a required

garage, others do not.

• Time limits on the length of the construction period, for example the exterior

completed within six months from the start of work, and the interior completed

within 12 months.

• Conditions that the dwelling may only be occupied as a residence, once a

Code Compliance Certificate has been issued.

• Requirement for the completed dwelling to be of at least a minimum value.

• Restrictions on look, shape, and form. This includes no dwelling should have

the same plan, building shape or use the same materials as any other within

250 metres of the land, only single level dwellings permitted, or in another

case have a minimum of two levels. No bright or vibrant colours can be used

on dwellings. Many covenants have a requirement for a garage, and for it to

be attached to the dwelling.

• Controls on the types of construction materials that can be used, including the

prohibition of recycled or reused materials. Some include rules on the types of

cladding and roofing to be used e.g. roofing can only be slate, tile or a pre-

coloured steel.

• The requirement to ensure regular maintenance to dwellings and to ensure

they look neat and tidy.

• No accessory dwellings (also called minor household units or granny flats) are

permitted.

• No prefabricated houses, or relocatable houses; in some cases they were

permitted, but only with developer approval.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 6

• No structures other than dwellings are to be built on the land; this includes

shed, huts, or carports. Storing of caravans is also prohibited.

• If a dwelling is damaged or destroyed, any rebuilt dwelling must be to

substantially the same specifications, be materially the same in look, and use

materials not unlike the original.

Amenity

• Rules on landscaping and fencing, including landscaping plan must be

approved by the developer, minimum and maximum number of trees allowed

in the front yard, along with minimum and maximum heights of the trees. Also,

for fencing, restrictions on the location (some ban fences in front yards),

heights, and types of materials (for example, no corrugated iron or fibrolite)

that can be used. In some cases no garden sheds permitted, or restrictions,

such as they cannot be seen from the road, or from a neighbouring property.

• Clotheslines are only permitted if they cannot be seen from the road.

• Restrictions on the size and location of aerials/antennae and satellite dishes,

including rules stating that they cannot be visible from the street.

• Limitation on the size of letterboxes, including the types of material that can be

used.

• Signs and advertising are banned, except for signs used to market the

property for sale (size limits may apply). ‘For rent’ signs are forbidden.

• Occupants of houses are not allowed to park caravans, boats, trailers, trucks,

commercial vehicles or vans. One stated that owners are not permitted to park

on the street, ever. Also vehicles that are in a poor state of repair, damaged,

used for agriculture, or heavy, are prohibited.

• Requirement to remove graffiti within 48 hours of it being carried out.

• No outdoor furniture of any kind in the front yard.

Other

• Owners won’t permit noise which might be found to be offensive or a nuisance

to others.

• Owners are not permitted to object or impede to any future plans of the

subdivision’s developer.

• Restrictions on animals, including a ban on cats, and animal that may cause

nuisance or annoyance, and a ban on certain dog breeds.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 7

• Restriction on utility operators that can be used, one covenant viewed only

permitted the use of Telecom New Zealand as the telephone provider.

Enforcement

2

• Often covenants include fines for non-compliance, such as $500 per day of

breach, a one off penalty of at least $20,000, or a penalty of 25 per cent of the

dwelling’s value.

• Permission for the developer to enter the land with 48 hours’ notice to monitor

compliance with the covenant.

An example of a schedule of covenants for a residential subdivision in Auckland can

be found in Appendix A.

The passing of the Property Law Act in 2007 meant that both positive and negative

covenants could apply to land (Hinde et al., 2018). Prior to this, all covenants needed

to be expressed in negative terms, even if they required the owner of the land to do

something (Norris Ward McKinnon, 2011). In most other jurisdictions only restrictive

(negative) covenants are permitted.

2.2.2 Heritage

Covenants can also be used to protect heritage, under the Reserves Act 1977. The

Act allows for private land owners to protect private land that “possesses such

qualities of natural, scientific, scenic, historic, cultural, archaeological, geological, or

other interest that its protection is desirable” (Reserves Act 1977, p. 121). Such

covenants are included in the Christchurch City Council’s Heritage Conservation

Policy, which states that the council will use them as a mechanism to “protect

buildings, places and objects of heritage value” (Christchurch City Council, 2007).

The Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014 also includes specific

provisions for heritage covenants as a mechanism to protect historic places, such as

private homes and other buildings, archaeological sites, and sites of significance to

Maori (Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, n.d.).

2

A number of the covenants around enforcement are designed to be applied during the construction

period and would be enforced by the subdivision developers, but others would require enforcement by

owners of dominant land under a covenant, or other land owners in a mutual covenant scheme. All of

these would need to be done through an application to the Court.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 8

2.2.3 Conservation

Given their widespread use in New Zealand, land covenants for conservation should

also be mentioned. Land covenants for conservation include those for open

space, conservation purposes, to preserve the natural environment, for heritage,

sustainable management, and in relation to Crown forestry licences for protection of

sites that have archaeological, historical, spiritual, emotional, or cultural significance,

water and soil, forest research areas and wahi tapu (Hinde et al., 2018). Areas of

private land, deemed to “preserve the natural environment, or landscape amenity, or

wildlife or freshwater-life or marine-life habitat, or historical value” can be covenanted

for conservation purposes under section 77 of the Reserves Act (Reserves Act 1977,

p. 122).

The most widely known covenants for conservation in New Zealand are those related

to Queen Elizabeth II National Trust, known colloquially as QEII covenants. The QEII

Open Space Covenant scheme, sees QEII partner with land owners to voluntarily

protect land and water bodies that are of “aesthetic, cultural, recreational, scenic,

scientific or social interest or value” (Queen Elizabeth II National Trust, 2011). QEII

covenants are put in place by land owners who want to help protect areas of their

property that they and the QEII trust consider of ‘value’. While owners often covenant

the land for selfless reasons to protect areas, there are also a number of benefits.

These include the QEII Trust advising property owners on the management of the

land, providing monitoring of the land, and support for fencing, weed and control,

restoration planting, and even rates relief (Queen Elizabeth II National Trust, 2018).

Other benefits to the land owner can include covenanted areas providing shade and

wind protection (Johnston, 2003), bush can help prevent slips and erosion and bring

back native birds, and wetlands can act as water filters and act as run-off retainers

(Orr, n.d.). The QEII trust has protected around 180,000ha (at 30 June 2014) of land

with covenants, protecting features including native forest, wetlands, high country,

coastlines, and cultural and archaeological sites (Queen Elizabeth II National Trust,

2011).

2.2.4 Condition of resource consent

Another use for covenants is under Section 108 of the RMA. While most land

covenants are between two private parties, covenants can also be required as a

condition of a resource consent issued by a consenting authority (local or regional

council). This is done through a consent notice, which is registered against a property

title, and includes the conditions required to be complied with under the consent

(Quality Planning, n.d.). Under section 221 of the RMA, a consent notice is deemed

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 9

to be “a covenant running with the land when registered under the Land Transfer Act

1952, and shall, notwithstanding anything to the contrary in section 105 of the Land

Transfer Act 1952, bind all subsequent owners of the land” (Resource Management

Act 1991, p. 457). Examples of covenants being used as part of the resource

consenting process in Auckland include the rural subdivision rules in the former

Rodney District. Aspects of the rules required the protection of vegetation and other

areas by covenant (Auckland Council, 2011). Similar provisions requiring covenants

to protect areas are also proposed in the rural subdivision rules of the Auckland

Unitary Plan

3

(Auckland Council, 2016).

2.2.5 Non-complaint

Covenants can also be used to address reverse sensitivity issues, though the use of

a 'restrictive non-complaint covenant'. Central Auckland’s Britomart Precinct has

restrictive non-complaint covenants preventing complaints about noise effects

generated by Ports of Auckland, with the covenant required under council’s planning

documents (Auckland Council, 2016). A second example of a restrictive non-

complaint covenant is in Albany, where North Shore City Council required land

owners looking to develop apartments next to North Harbour (QBE) Stadium to future

proof against noise complaints (Thompson, 2007).

2.3 Land covenants in overseas jurisdictions

Land covenants are a popular mechanism of private land use control in the United

Kingdom. While covenants are widely used, unlike New Zealand, there are

processes in place to cancel or modify covenants where they are deemed to be out

of date. In Scotland a tribunal system is used, to assess the modification of

cancellation of covenants. (Adams, Disberry, Hutchison, & Munjoma, 2001) note that

there are cases where covenants that prevented redevelopment in the centre of

towns being cancelled to facilitate higher-density developments. In England

applications can be made to a tribunal for restrictive covenants to be discharged or

modified if it can be shown that that the restriction is obsolete on the basis of

changes in the neighbourhood or the property (Brading & Styles, 2017).Covenants

can also be discharged or modified by the tribunal where covenants are shown to

limit or impede some reasonable use of the land for public or private purposes, with

decisions on applications taking into account any relevant planning documents (Lee,

2017).

3

The rural subdivision rules of the Auckland Unitary plan are not yet operative, and at the time of

writing this report were still under appeal in the Environment Court.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 10

Edmonton, in Alberta, Canada has been struggling with the redevelopment of parts of

the city where restrictive covenants only allow single stand-alone houses, or have

been used to exclude grocery stores (Ziff & Jiang, 2012). Currently, like New

Zealand, there are few options available to discharge covenants that prevent

redevelopment, except through expropriation schemes

4

(Ziff & Jiang, 2012).

Suggestions for law reform to allow judicial power to discharge out of date covenants

has been mooted, along with proposals that would allow municipal authorities to

impose time limits for new covenants, or allow them the ability to respond to

covenants that affect their power (Ziff & Jiang, 2012).

Restrictive covenants have a long history in the United States, and were used before

the development of public zoning by local governments as a method of land use

control, often by land developers (Deng, 2003). The covenants were used as a way

to prevent incompatible land use conflicts and their potential effects of property

devaluation (Fischel, 2004). In Houston, Texas, there are still large swathes of the

city that have no zoning, instead privately established covenants are used to control

land use (Buitelaar, 2004) and also to control aesthetics (Korngold, 2001). Covenants

have also been used to bar commercial activities in residential areas, to shape

physical characteristics of suburbs, as well as their historical use to influence the

social sphere – particularly through the now illegal use as a method to prevent sales

to non-white buyers (Dehring & Lind, 2007). The near-universal use of land use

planning in towns and cities across the country has led to complex conflicts between

covenants and planning rules, but with covenants often outweighing planning rules

when tested in the courts (Berger, 1964). Most states have no statutory mechanism

to remove covenants or for their modification, but common law doctrine of ‘changed

conditions’ has led to their modification or termination (Walsh, 2017). Many states

currently use covenants ‘not to sue’ on contaminated brownfield sites

5

. The

covenants are used to encourage redevelopment by the State waiving the right to

sue for clean-up costs from innocent purchasers of polluted sites (those not

responsible for causing the contamination) (Andrew, 1996). Restrictive covenants,

like in New Zealand, are being used in modern subdivisions, with covenants used to

empower homeowner associations to administer and enforce covenants (Korngold,

2001). In 1975 estimated that 2.85 per cent of housing units in United States were in

homeowner association developments, in 1998 that estimate has risen to 14.67 per

4

An expropriation scheme is similar to New Zealand’s compulsory acquisition powers under the Public

Works Act 1981.

5

In the United States the term brownfield is defined by the United States Environmental Protection

Agency (n.d.) as “property, the expansion, redevelopment, or reuse of which may be complicated by

the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant”.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 11

cent (Korngold, 2001). Covenants have also been used for conservation purposes,

as in here in New Zealand (Mahoney, 2002), and as a method to protect solar and

wind resources (Newman, 2000)

Covenants are also used in Australia, particularly for private residential estates

(Kenna, Goodman, & Stevenson, 2017), and both New South Wales and Victoria,

unlike New Zealand, have mechanisms to remove covenants (with varying levels of

effectiveness). In New South Wales, the Environmental Planning and Assessment

Act 1979 specifically enables planning instruments to override restrictive covenants

(Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979). Research by Taylor and

Rowley (2017) notes that in Victoria, prior to 2000, covenants were treated external

to planning and were dealt with through property law. Legislative changes made in

2000 included provisions allowing planning instruments and processes to be used to

remove or vary covenants, but poorly devised legislation meant that a number of

issues still remained. Further changes have meant that the outcome is that

covenants now have a privileged status in the planning process, and they are hard to

remove and continue to trump public interest arguments (Taylor & Rowley, 2017).

2.4 The effects of land covenants

2.4.1 Form of land use control

Covenants act as a form of land control. In Houston, Texas, private restrictive

covenants are widely used to control land uses and urban development in the place

of a formal planning and zoning system (Buitelaar, 2009). In many parts of the world,

including New Zealand, land covenants are used to encourage conformity such as

how a house should look (Ziff & Jiang, 2012) or restrict further development (Kenna

et al., 2017). In New Zealand covenants sit outside the planning system but often

impose more restrictive rules than set out in statutory planning documents. In some

cases covenants prevent more intensive use of land than plans allow and there is

little councils can do to prevent or alter them (New Zealand Productivity Commission,

2015). While similar examples are also seen overseas (Kenna et al., 2017), some

jurisdictions have introduced processes that prevent rules of public planning

documents being undermined by private covenants (Mead & Ryan, 2012; Taylor &

Rowley, 2017). Covenants can also be used in New Zealand to control land use,

which can also act as a barrier to development and intensification. This includes

when the inclusion of a covenant is required as a condition of a resource consent,

particularly in rural or peri-urban areas. Covenants in these cases can include

requirements to protect vegetation or other natural features, or prevent development

through prohibiting further subdivision. While covenants in these cases may prevent

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 12

intensification, they could be considered justified as they are used a mechanism to

generate other benefits, such as environmental protection.

2.4.2 Barrier to development and redevelopment

The New Zealand Productivity Commission (2015) have identified land covenants

and their restrictive nature as a barrier to both development and redevelopment, by

restricting the current and future capacity for additional dwellings of land. The

Commission also noted that when covenants specify the requirements for types of

materials to be used in a development they can prohibit efficient building techniques,

including the use of building materials that may be developed in the future. A

submission to the Commission in their investigation revealed how land covenants

have been used as a barrier to development on neighbouring land, with a covenant in

Tauranga used to prevent the provision of road access or services to adjoining land

zoned for residential development (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2015).

Mead and Ryan (2012) indicate that they believe that covenants operating in

perpetuity could thwart strategic planning objectives for intensification. Mead and

Ryan further note that the absence of covenants in older areas but their presence in

modern subdivisions “will mean that intensification pressures may be concentrated in

areas less suitable for urban change, such as areas with earlier period or character

housing” (2012, p. 4). Existing land covenants were also noted as contributing to the

challenge of the Christchurch rebuild following the earthquakes that affected the city

by MBIE’s chief architect (Joiner, 2012).

Land covenants were also indicated as a barrier to development in overseas

jurisdictions. Research in Australia has highlighted that the use of land covenants on

residential properties in the City of Darebin, in greater Melbourne, will be a constraint

on future housing growth (City of Darebin, 2011). In Sydney the proliferation of

private residential estates with covenants are seen as an inhibitor to infill

redevelopment and increased densities (Kenna et al., 2017). In England and

Scotland, covenants can impact the development process, but can be overcome with

relative ease (Adams & Hutchison, 2000; Walsh, 2017). In the United States

covenants are noted as a constraint, particularly to ‘brownfield’ redevelopment

6

(Adams et al., 2001), and in the Netherlands heritage covenants were identified as a

barrier to redevelopment, with an example noted where they had a “large impact on

the estimated for land development costs, causing a delay in the planning process”

(Baarveld, Smit, & Dewulf, 2018, p. 109).

6

Refer to footnote 4.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 13

2.4.3 Effects on house prices and affordability

In residential areas, land covenants can affect house prices and affordability. Given

covenants are put in place to either restrict what can happen or require an action, it is

unsurprising. The NZPC in their report on housing affordability noted that in New

Zealand, land covenants increased the cost of housing by often having direct

requirements that minimum costs or size be met. and also by requiring the use of

certain building techniques and materials (New Zealand Productivity Commission,

2012). Covenant restrictions mean that it is often impossible for affordable housing

options to be constructed, either through requirements for a minimum floor space

size or restrictions on housing typology (Easton, Austin, & Hattam, 2012). Covenants

can also add to transaction costs in the development process, adding expense and

time (Buitelaar, 2004; Dally, 2013), and so increasing the cost of housing. Over the

last decade there have been numerous comments in New Zealand media about how

covenants prevent affordable housing. Some of the commentary includes:

• Developers using covenants, in conjunction with development staging, as a

mechanism to stop the construction of smaller or affordable houses, and thus

increasing the value of land and sale price of homes for later stages

(Stevenson, 2018).

• The use of covenants that restrict smaller houses, increasing build costs and

therefore increasing unaffordability (McDonald, 2017). One example is of a

retiring couple wanting a smaller home but finding that new subdivision

covenants prevent them from building a home to fit their needs (Rikihana

Smallman, 2017).

• The exclusion of pre-made, pre-fabricated, or relocatable houses, all of which

are often cheaper methods of building, from new subdivisions (Dally, 2013;

Heyward, 2018).

• Neighbouring residents of a proposed co-housing development in Flaxmere

want it to be subject to the same covenants as their properties, which include

minimum dwelling size requirements, integrated garages and internal

boundary fencing (Harper, 2018).

While there has been no economic assessment of the effects of covenants in New

Zealand, there has been in the United States. Research by Speyrer (1989) showed

that in Houston, Texas, houses that were in neighbourhoods which had private

covenants had significant premiums compared to identical houses without covenants.

Speyrer also found that the use of covenants to protect from externalities were more

valuable than any forgone development opportunities – this means that the benefits

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 14

of being in a covenant scheme were greater than the disbenefits of having to comply

with covenant rules. In Louisiana, analysis by Hughes and Turnbull (1996) revealed a

number of relevant points, including:

• That restricting utilities (such as power and phone) to being underground

increased house prices

• The requirement to mow lots, decreased prices

• Restrictions on prefabricated houses and on drilling had no effects

• Constraints such as no signs, and parking and dumping restrictions also

increased house prices.

Hughes and Turnbull also observed that stricter restrictions have a diminishing price

effect as neighbourhoods mature, and perhaps most importantly covenants

increased house price by about six per cent in 10-year-old neighbourhoods and by

two per cent in 20- year-old neighbourhoods. A note here that covenants in Louisiana

can only have a 20-year lifespan, after which they can be renewed, perhaps

accounting for the low margin on their benefits after that length of time. Analysis by

Rogers (2006, 2010) showed that properties with covenants governed by residential

community associations had a premium of about two to three per cent, and that the

marginal price of covenants falls to zero after 25 years if a covenant is not renewed.

2.4.4 Covenants used to stifle competition

Covenants are sometimes used as a mechanism to control or restrict business

activity, and can be used to stifle or reduce competition in a market (OECD, 2010) .

In Edmonton, Canada, research by Ziff and Jiang (2012) notes an example where

supermarket firms relocate their stores to a new location and sell the existing site,

placing a covenant on the land that prevents any future owner from operating a

supermarket on the site. Other examples of covenants used for these purposes

include a fast food chain selling a restaurant site and inserting a covenant that

prevents beef-based fast food being sold, or a former private hospital site having a

covenant preventing another hospital operating on the land in the future (OECD,

2010). Ziff and Jiang (2012) further note that such uses of covenants have

contributed to reduced competition and customer choice, and the creation of what

are referred to as ‘food deserts’

7

.

7

A food desert is defined in United States of America legislation as being an area “with limited access

to affordable and nutritious food, particularly such an area composed of predominantly lower-income

neighbourhoods and communities” (Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008).

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 15

As noted in earlier, in New Zealand covenants can be ruled invalid if they violate the

Commerce Act 1986. The Act states that covenants shall not have the effect of

“substantially lessening competition in a market” (Commerce Act 1986). Although

covenants cannot be used to substantially lessen competition, they can be used to

lessen it none the less. An Auckland example of the use of a covenant to prevent

competition is the former Village 8 cinema site on Crown Lynn Place in New Lynn

(Figure 1). The owner closed the cinema complex in June 2001, when it opened a

new cinema complex in Henderson’s WestCity Waitākere mall (then known as

Westfield WestCity). When the site was sold, including the cinema complex building,

a covenant was placed on it preventing any future land owner operating a cinema

complex on the site (and interestingly any single retail shop with a floor area less

than 400 square metres) (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Former Village 8 cinema complex site in New Lynn

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 16

Figure 2: Covenant text for former Village 8 cinema site, New Lynn (CT# NZ960/262)

2.4.5 Covenants as a mechanism of exclusion

Covenants can be used as a method of exclusion, either explicitly or surreptitiously.

An historic example, and perhaps the most well-known, use of land covenants to

exclude was their application across the United States to exclude non-whites from

some suburbs (Jones-Correa, 2000). By 1940, 80 per cent of property in Chicago

and Los Angeles had restrictive covenants excluding black families (United States

Commission on Civil Rights, 1973). Despite racial restrictive covenants being ruled

unenforceable in 1948, Berry (2001) poses that other types of private covenants may

play a part in racial and economic segregation in residential areas of Houston and

Dallas. Covenants mandating that homeowners pay for amenities in a development,

have been raised as a method of exclusion – deterring undesired residents, that is

lower-income households, from purchasing homes (Strahilevitz, 2006). Restrictive

covenants only allowing single-family homes have been used to prevent the

establishment of group homes or shelters for people with mental disabilities in the

US, although a few states have enacted laws to counter such covenants (Salsich,

1986).

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 17

3.0 Method to identify titles with land covenants in

Auckland

The datasets used to identify titles that had land covenants, as at February 2018, are

listed below (Table 1).

Table 1: List of data sources and descriptions used in modelling

Data Description Format Organisation; source

NZ title

memorials list

List information relating to a transaction,

interest or restriction over a piece of

land, including mortgages, discharge of

mortgages, transfer of ownership, and

leases. Data in table is for both current

and historic memorials, and also

provides a high-level memorial

description. (Land Information New

Zealand, 2017)

Table

Land Information New

Zealand; LINZ Data

Service

NZ property

titles

Spatial extent of property titles, including

a record of all estates, encumbrances

and easements that affect a piece of

land. (Land Information New Zealand,

2017)

Spatial/GIS

Land Information New

Zealand; LINZ Data

Service

Auckland

Council local

board

boundaries

Polygons indicating the extents of the

local board areas for Auckland.

Spatial/GIS

Statistics New

Zealand; 2013

census-based

geographic boundary

files

Zoning

(Auckland

Unitary Plan,

operative in

part)

Extents of zoning defined by polygons

for the Auckland Unitary Plan, operative

in part (as at November 2016)

Spatial/GIS

Auckland Council;

SDE

8

8

SDE refers to Auckland Council’s ArcGIS geospatial repository

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 18

The creation of a dataset of titles with land covenants in Auckland is a multi-step and

multi-output process (Table 2). Each dataset output is an intermediate dataset used

for further processing, or an output dataset in its own right, that is used for analysis.

Table 2: Method for creating land covenant dataset for Auckland

Step

No.

Name Description

One

Create core

dataset

Joining current

9

memorial text to titles (spatial file), and extracting only

those that have a ‘land covenant’ recorded (Output 1). This output creates

one polygon per land covenant.

Two

Tag core

dataset with

additional data

Take land covenant dataset (Output 1) and tag the titles (spatial file) with

the Auckland Unitary Plan (operative in part) zone and local board (Output

2).This dataset is used as the input for steps three, four and five.

Three

Number of

covenants

Take tagged land covenant dataset (Output 2) and filter out those not on

land (in the General Marine Zone), and those that are cross leases (Output

3). This dataset is used to calculate the number of land covenants.

Four

Number of

titles

Take tagged land covenant dataset (Output 2) and remove duplicate titles,

i.e. those that have more than one covenant on them (Output 4). This

dataset is used to calculate the number of titles with land covenants.

Five Land area

Take tagged land covenant dataset (Output 2) and remove duplicate titles

that have more than one covenant on them, and then “flatten” the title

dataset (remove duplicate title shapes, where there is more than one title

per shape, such as with unit titles) (Output 5). This dataset is used to

calculate the land area covered by land covenants.

Each of the datasets outputted is saved as a geodatabase file (a spatial or GIS file

that can be used in mapping software), and then if required exported and saved as

an MS Excel file for creating tables for analysis.

3.1 Caveats, limitations, and notes on outputs

As with many datasets and analysis, there are a number of important things to note

about the data. For the data and analysis created for this report, the following should

be noted:

• The title data downloaded from the LINZ data portal was dated 27 January

2018.

• Auckland Unitary Plan (operative in part) zoning data was as at 8 November

2016.

9

The NZ title memorials list dataset from LINZ contains all current and historic memorials. Current

memorials are those that are currently in effect and/or are for titles that presently exist. Historic

memorials are those that are no longer in effect and/or for titles that no longer exist. As part of this

process all historic memorials were filtered out.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 19

• All titles that are registered as a cross lease have been filtered out of analysis,

as all cross lease titles have a land covenant registered in their memorial.

Cross leases have been excluded from this analysis as they have been

addressed in Fredrickson (2017); that analysis showed that there were 99,829

cross lease titles in Auckland on 39,636 properties.

• For analysis, the results exclude those titles that were identified as being in

the ‘General Coastal Marine’ zone; this was because these titles are not on

land.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 20

4.0 Analysis

Land covenants, excluding those on cross lease titles, are spread across the entire

region, in areas of both rural and urban character (Figure 3Figure 2). In Auckland

there are 151,170 land covenants on 96,261 titles. Seventeen per cent of titles in the

region have a land covenant on them. The land area of titles with a covenant on

covers an area of 60,757 hectares, or 12 per cent of Auckland’s land area.

Figure 3: Titles with land covenants in Auckland

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 21

4.1 Land covenants by local board

All 21 of Auckland’s local boards have titles that are affected by land covenants, but

two-thirds of the titles with covenants are in just six local board areas. Howick Local

Board has the largest number of titles affected by land covenants, 18,261, which is

38 per cent of the total titles in that area and 19 per cent of the regional total of titles

affected by land covenants. Two other local board areas have more than 30 per cent

of titles in their area with covenants; Upper Harbour Local Board area has 46 per

cent (11,414), or 12 per cent of the region total, and Papakura with 34 per cent

(6618, or seven per cent of the region total). All of these areas have large residential

areas that have been developed in the last 20 years. Other local boards with high

numbers of titles with land covenants are Hibiscus and Bays (11,741, or 12 per cent

of the regional total), and the two rural local boards, Rodney (8981) and Franklin

(8893, or nine per cent of the regional total). Conservation covenants and covenants

preventing further subdivision, both often used as conditions in the resource

consenting process, may be the cause for this.

Table 3: Number of titles, land covenants, and titles with land covenants in Auckland,

by local board area

Local board name

Total

number

titles in

local

board

Number of

land

covenants

Number of

titles with a

land

covenant

Proportion of

total titles

with a land

covenant

Proportion of

regional total

of titles with a

land

covenant

Albert - Eden

34,663

960

817

2%

1%

Devonport - Takapuna

22,545

1,076

907

4%

1%

Franklin

31,127

11,096

8,893

29%

9%

Great Barrier

1,538

109

83

5%

0%

Henderson - Massey

38,048

8,841

6,673

18%

7%

Hibiscus and Bays

41,644

17,990

11,746

28%

12%

Howick

47,507

23,180

18,261

38%

19%

Kaipātiki

30,866

1,838

1,564

5%

2%

Mangere - Otahuhu

19,416

21,580

1,694

9%

2%

Manurewa

24,360

7,045

6,225

26%

6%

Maungakiekie -

Tamaki

28,644 1,393 914 3% 1%

Ōrākei

32,856

4,416

3,409

10%

4%

Otara - Papatoetoe

21,770

2,909

885

4%

1%

Papakura

19,556

10,601

6,618

34%

7%

Puketāpapa

17,615

822

756

4%

1%

Rodney

32,061

14,337

8,981

28%

9%

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 22

Local board name

Total

number

titles in

local

board

Number of

land

covenants

Number of

titles with a

land

covenant

Proportion of

total titles

with a land

covenant

Proportion of

regional total

of titles with a

land

covenant

Upper Harbour

24,573

14,871

11,414

46%

12%

Waiheke

6,902

490

392

6%

0%

Waitakere Ranges

19,165

1,908

1,678

9%

2%

Waitematā

54,402

4,284

3,102

6%

3%

Whau

25,676

1,424

1,249

5%

1%

Total

574,934

151,170

96,261

17%

-

The local board areas where the land area of titles with a land covenant add up to the

most hectares are Rodney and Franklin which together comprise three-quarters of

the region’s total land area affected by land covenants. Titles with land covenants in

Rodney add up to 28,703 hectares, which is 13 per cent of the total area of the board

and half the regional total of affected land area, while Franklin’s titles with land

covenants cover 14,955 hectares, 12 per cent of the board’s land area – a quarter of

the regional total. The land area of titles with land covenants in the Howick Local

Board cover close to half (48 per cent) of the board’s land area, but only five per cent

of the regional total. The only other local board with more than 30 per cent of land

area affected by covenants is Mangere-Otahuhu (39 per cent), but its affected area

(2031 hectares) is only three per cent of the regional total. Hibiscus and Bays has 29

per cent of its land affected, or 3147 hectares (five per cent of the regional total).

Table 4: Total land area of titles with a land covenant, by local board area, in Auckland

Local board name

Total land area

in local board

(ha)

Land area of

titles with

covenant (ha) in

local board

Proportion of

total land area of

titles with

covenant in

local board

Proportion of

total area of

titles with

covenant in

region

Albert - Eden

2,834

138

5%

0%

Devonport - Takapuna

2,113

72

3%

0%

Franklin

119,752

14,955

12%

25%

Great Barrier

32,066

518

2%

1%

Henderson - Massey

5,321

566

11%

1%

Hibiscus and Bays

11,006

3,147

29%

5%

Howick

6,969

3,376

48%

6%

Kaipātiki

3,384

226

7%

0%

Mangere - Otahuhu

5,247

2,031

39%

3%

Manurewa

3,712

735

20%

1%

Maungakiekie -

Tamaki

3,642 137 4% 0%

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 23

Local board name

Total land area

in local board

(ha)

Land area of

titles with

covenant (ha) in

local board

Proportion of

total land area of

titles with

covenant in

local board

Proportion of

total area of

titles with

covenant in

region

Ōrākei

3,225

299

9%

0%

Otara - Papatoetoe

3,706

562

15%

1%

Papakura

4,072

858

21%

1%

Puketāpapa

1,872

110

6%

0%

Rodney

227,495

28,703

13%

47%

Upper Harbour

6,973

1,861

27%

3%

Waiheke

15,476

702

5%

1%

Waitakere Ranges

30,403

1,345

4%

2%

Waitematā

1,939

163

8%

0%

Whau

2,685

255

9%

0%

Total

493,891

60,757

12%

-

4.2 Land covenants by zoning

Assessing titles and land covenants by their zoning allows some insight into how

areas of the city are affected, either now or in the future. This section breaks down a

number of zoning groups and analyses the number of titles in each zone, the

numbers with a land covenants, and the area that they cove. A full table of all

Auckland Unitary Plan (operative in part) zones and statistics can be found in

Appendix B (numbers of titles) and Appendix C (land area of titles).

4.2.1 Residential zones

Residential zones contain 83,068 titles that are affected by land covenants, or 19 per

cent of the total number of titles in those zones; 86 per cent of all titles affected by

covenants in Auckland are in residential zones (Table 5). These titles cover an area

of 8685 hectares, 23 per cent of the area of the zones; 14 per cent of total land area

affected by covenants in Auckland is in residential zones (Table 6). Residential

zoned titles with land covenants are concentrated in greenfield suburbs that have

been developed over the last few decades, such as Long Bay, Greenhithe, West

Harbour, Flat Bush, and Karaka. Close to half (42,450, or 44 per cent) of all titles with

land covenants are located in the Mixed Housing Suburban zone, another quarter

(23,567, or 24 per cent) being in the Single House zone, and a tenth (9,992) being in

the Mixed Housing Urban zone.

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 24

Table 5: Number of titles, land covenants, and titles with land covenants in Auckland,

2018, by residential zones of the Auckland Unitary Plan (operative in part)

Zone name

Number

titles

Number of

land

covenants

Number of

titles with a

land

covenant

Proportion

of total titles

in zone with

a land

covenant

Proportion

of total titles

with a land

covenant in

region

Large Lot

6,879

1,622

24%

<1%

2%

Mixed Housing Suburban

199,468

42,450

21%

10%

44%

Mixed Housing Urban

100,687

9,992

10%

2%

10%

Rural and Coastal

settlement

5,841 727 12% <1% 1%

Single House

86,191

23,567

27%

5%

24%

Terrace Housing and

Apartment Buildings

42,415 4,710 11% 1% 5%

Total

441,481

83,068

19%

19%

86%

Table 6: Area zoned and area covered by land covenants in Auckland, 2018, by

residential zones of the Auckland Unitary Plan (operative in part)

Zone name

Total zoned

area (ha)

Zoned area

that has land

covenant (ha)

Proportion of

total zoned

area with land

covenant

Proportion of

total area of

titles with

covenant in

region

Large Lot

2,912

887

30%

1%

Mixed Housing Suburban

14,970

3,608

24%

6%

Mixed Housing Urban

7,531

851

11%

1%

Rural and Coastal settlement

1,856

399

21%

1%

Single House

8,539

2,604

30%

4%

Terrace Housing and

Apartment Buildings

2,485 337 14% 1%

Total

38,293

8,685

23%

14%

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 25

Figure 4: Titles with land covenants in residential zones (in Auckland’s urban core),

2018

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 26

Title issue date can be used to analyse the proportion of titles in residential zones

with and without land covenants over time. The analysis shows residential titles the

proportion of titles with land covenants has been increasing over time. Less than 10

per cent of residential titles issued in the early 1980s had a land covenant on them.

In 2017, over 50 per cent of residential titles issued had a land covenant on them.

The proportion of titles issued pre-1980 (not shown on graph) show only small

proportions of titles with covenants – two per cent or less prior to 1964, with the

proportion increasing through the 1970s. The early 1980s saw a slight dip, but has

been increasing steadily since.

Figure 5: Proportion of current titles in residential zones with land covenants, by year

of title issue, Auckland, 1980-2017

4.2.2 Centre zone

Centre zones, including the city centre (CBD), metropolitan centres, and other

centres are areas of the city that are expected to accommodate large amount of floor

space and high numbers of apartments as the city intensifies. These zones contain

2529, or three per cent of the regional total, of the of titles affected by covenants

(Table 7); Titles in the centre zones affected by covenants cover a land area of 336

hectares, or 23 per cent of the total combined area of the zones (Table 8). The City

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 27

Centre zone has the highest number of titles affected by land covenants, with 1616,

with the area of titles with covenants in in the Metropolitan Centre zone covering 108

hectares.

Table 7: Number of titles, land covenants, and titles with land covenants in Auckland,

2018, by centre zones of the Auckland Unitary Plan (operative in part)

Zone name

Number

titles

Number of

land

covenants

Number of

titles with a

land

covenant

Proportion

of total titles

in zone with

a land

covenant

Proportion

of total titles

with a land

covenant in

region

City Centre

28,824

2,573

1,616

6%

2%

Local Centre

2,404

343

150

6%

<1%

Metropolitan Centre

5,436

903

426

8%

<1%

Neighbourhood Centre

1,994

57

43

2%

<1%

Town Centre

6,382

407

294

5%

<1%

Total

45,040

4,283

2,529

6%

3%

Table 8: Area zoned and area covered by land covenants in Auckland, 2018, by centre

zones of the Auckland Unitary Plan (operative in part)

Zone name

Total zoned

area (ha)

Zoned area

that has land

covenant (ha)

Proportion of

total zoned

area with land

covenant

Proportion of

total area of

titles with

covenant in

region

City Centre

261

104

40%

<1%

Local Centre

246

59

24%

<1%

Metropolitan Centre

382

108

28%

<1%

Neighbourhood Centre

132

12

9%

<1%

Town Centre

442

52

12%

<1%

Total

1,463

336

23%

1%

4.2.3 Rural zones

In rural zones over 5800 titles have a land covenant or 19 per cent of the total titles in

these zones (Table 9); they cover a land area of 41,000 hectares or two-thirds of

Auckland’s total covenanted land area (Table 10). Of all the rural zones, the

Countryside Living zone has the highest number (2507) and the highest proportion

(34 per cent) of its titles with land covenants. Titles with land covenants in the Rural

Production zone cover the largest area of any of the rural zones, covering 19,104

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 28

hectares or half of rural zone covenanted land and fully a third of total covenanted

land by area.

Table 9: Number of titles, land covenants, and titles with land covenants in Auckland,

2018, by rutal zones of the Auckland Unitary Plan (operative in part)

Zone name

Number

titles

Number of

land

covenants

Number of

titles with a

land

covenant

Proportion

of total titles

in zone with

a land

covenant

Proportion

of total titles

with a land

covenant in

region

Countryside Living

7,299

3,862

2,507

34%

3%

Rural Production

12,579

2,574

1,694

13%

2%

Mixed Rural

4,500

1,240

767

17%

1%

Rural Coastal

3,437

960

593

17%

1%

Waitakere Ranges

Foothills

1,200 185 141 12% <1%

Waitakere Ranges

2,169

134

122

6%

<1%

Rural Conservation

215

44

39

18%

<1%

Total

31,399

8,999

5,863

18%

6%

Table 10: Area zoned and area covered by land covenants in Auckland, 2018, by rural

zones of the Auckland Unitary Plan (operative in part)

Zone name

Total zoned

area (ha)

Zoned area

that has land

covenant (ha)

Proportion of

total zoned

area with land

covenant

Proportion of

total area of

titles with

covenant in

region

Countryside Living

22,592

6,953

31%

11%

Rural Production

165,169

19,104

12%

31%

Mixed Rural

39,077

6,185

16%

10%

Rural Coastal

77,770

7,397

10%

12%

Waitakere Ranges Foothills

3,141

317

10%

1%

Waitakere Ranges

2,870

314

11%

1%

Rural Conservation

3,093

992

32%

2%

Total

313,714

41,262

32%

68%

Land covenants in Auckland and their effect on urban development 29

4.2.4 Future Urban zone