THE IMPACT OF A-F LETTER GRADES

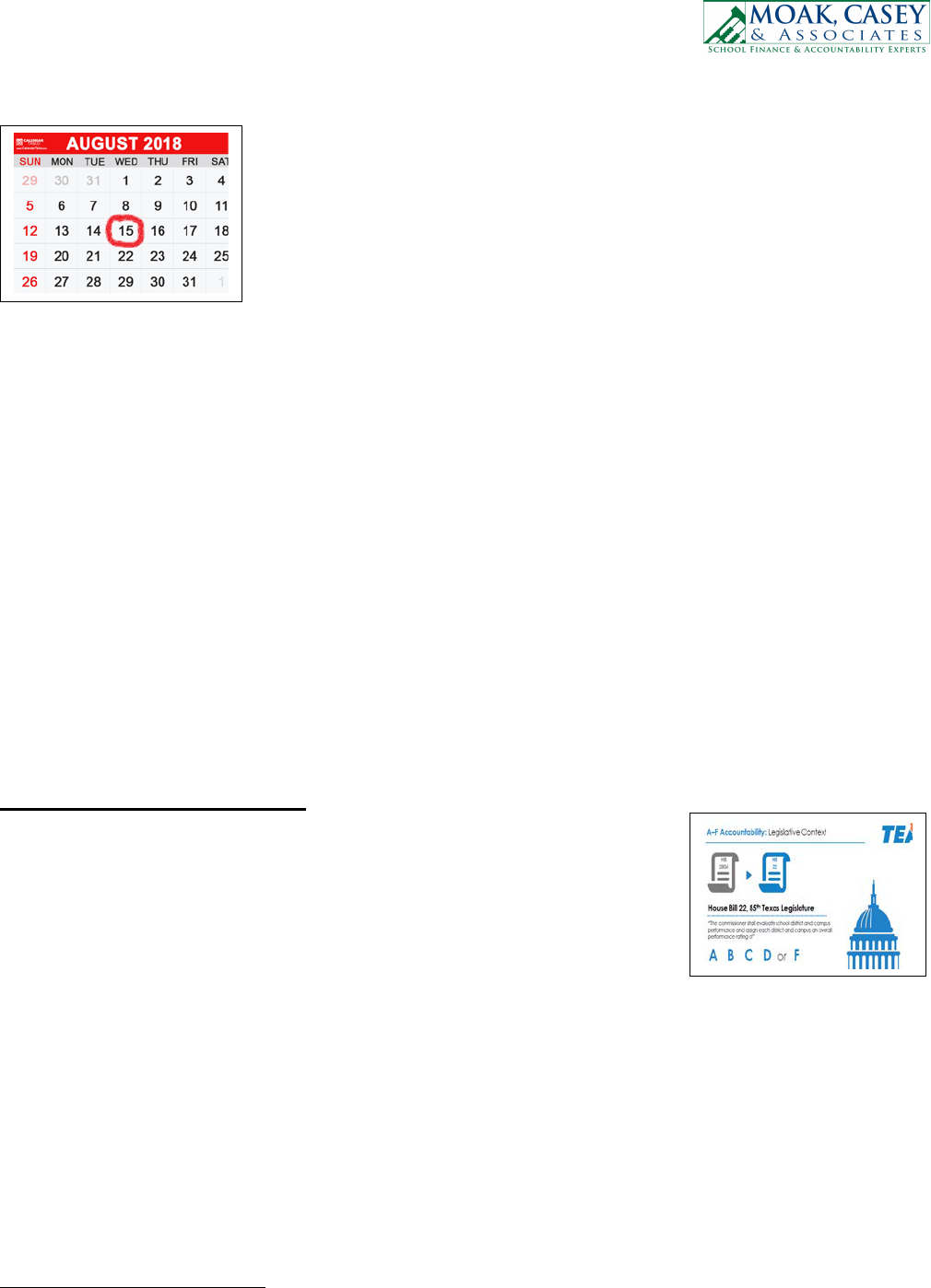

Circle, highlight, and underline this date on the calendar… August 15, 2018.

This is when the state will unveil the inaugural “A-F” letter grade ratings for

public school districts via the state’s academic accountability system. (TEA

will not issue campus-level A-F ratings until summer, 2019.) Regardless of

one’s beliefs about public education, accountability ratings in the form of A-

F letter grades will be critically important to virtually all of the education

system’s stakeholders: students, parents, teachers, campus administrators,

district administrators, school board members, neighborhoods and communities, pro-public education

advocates, pro-voucher advocates, realtors, business and industry leaders, the higher education system,

and officials (including elected officials) at the local, state and even federal levels.

No doubt there will be a plethora of media releases, informational brochures, and website updates prepared

in advance of the August 15 accountability ratings release. Some individuals and organizations will simply

total the number of D’s and/or Fs and issue a broad-brush declaration of failure, with the solution being

an immediate call for vouchers. Some will bemoan the K-12 system’s apparent failure to adequately

prepare students for postsecondary success. Some will tout the A-ratings given to their local school

districts on marquees and/or billboards. And some may dismiss the letter grades by observing that “…a

letter grade will not measure all of the great things we do in public education.”

1

To address the last statement, one must first understand “how we got here,” that is, the policy framework

within which the public education accountability system operates.

CURRENT LAW

What We Knew as of “Sine Die”

The 85

th

Regular Texas Legislature changed the education code by passing

HB 22, which requires the commissioner of education to: “measure and

evaluate school district and campuses with respect to: (1) improving student

preparedness for success in: (A) subsequent grade levels, and (B) entering

the workforce, the military, or postsecondary education; (2) reducing, with

the goal of eliminating, student academic differentials among students from

different racial and ethnic groups and socioeconomic backgrounds; and (3)

informing parents and the community regarding campus and district performance.” (TEC, §39.053(a-1))

Legislative action repealed the index system that had been used in the 2012 through 2017 ratings cycles.

Also repealed was the former statutory requirement to implement an A-F rating system (per HB 2804,

2015, 84

th

Texas Legislature), which would have evaluated schools and districts on five domains of

performance. Current law requires the commissioner to implement a new A-F rating system that comprises

three domains, referred to as the Student Achievement, School Progress, and Closing the Gaps domains,

respectively. (TEC, §39.053(c))

TEC, §39.0541 explicitly grants the commissioner broad authority to “adopt indicators and standards

under this subchapter at any time during a school year before the evaluation of a school district or

1

Superintendent’s Panel, Texas Tribune Festival. From Twitter, @MoakCasey, 23 Sept 2017

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

1

campus.” The law further states that “The commissioner shall evaluate school district and campus

performance and assign each district and campus an overall performance rating of A, B, C, D or F.”

(TEC, §39.054(a)) Statute defines A-F letter grades using terminology borrowed most recently from the

TAKS-based era of accountability, last applied in 2011 (TEC, §39.054(a)):

A = Exemplary Performance

B = Recognized Performance

C = Acceptable Performance

D = In Need of Improvement

F = Unacceptable Performance

The commissioner of education must assign each district and charter an A-F rating beginning in August

2018 and each campus an A-F rating beginning in August 2019. (TEC, §39.054(a-4)) When the Texas

Education Agency calculates an overall rating, the commissioner must select “whichever performance

rating is higher” between the Achievement and Progress domains [within certain limitations], and

combine that result with the letter rating assigned to the Closing the Gaps domain. The commissioner is

required to weight the Closing the Gaps domain as “no less than 30%” of the overall rating. (TEC,

§39.054(a-1)) The limitations specify that: 1) the commissioner cannot assign a composite rating higher

than a “B” if the district or school received an “F” rating in either the Achievement or the Progress domains

and 2) the commissioner cannot assign an “A” rating in a domain or overall if any of the district’s

campuses has a corresponding “D” or “F” rating. (TEC, §39.054(a))

Statute mandates that “The commissioner shall ensure that the method used to evaluate performance is

implemented in a manner that provides the mathematical possibility that all districts and campuses

receive an A rating.” (TEC, §39.054(b); emphasis added.) The agency effectively is prohibited from

developing a state accountability system that applies a forced statistical distribution, such as a percentile

rank, which would result in predetermined numbers or percentages of “A” or “F” ratings.

Statue also requires the commissioner to “solicit input statewide from persons who would likely be affected

by the proposed rule [pertaining to assessment and accountability], including school district boards of

trustees, administrators and teachers employed by school districts, parents of students enrolled in school

districts, and other interested stakeholders.” (TEC, §39.001(b))

The next sections of this opinion article are intended to inform stakeholders, especially district and campus

administrators, about how the new accountability system could impact schools, districts, and

communities.

2

The analyses identify potential issues with or limitations of the new accountability system.

Stakeholders may be most interested in providing feedback to TEA that can improve the system’s fairness,

accuracy and utility by addressing the already identifiable issues and/or limitations.

2

All descriptions, analyses, etc. are based on publicly available information as of January 31, 2018.

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

2

STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT DOMAIN

What We Know Now

Using the 2017 Texas Academic Performance Report (TAPR) data

and TEA’s published methodology

3

, Moak, Casey & Associates

(MCA) models suggest that campuses educating large numbers of

economically disadvantaged students will not be as likely as other

campuses to receive “A” ratings. In other words, while the statute

requires a “mathematical” possibility for all campuses to receive “A”

ratings, the draft policies set forth by the commissioner appear to have

a systematic bias making it more difficult for some schools than others to earn those ratings.

The scatterplots below display the MCA models for the Student Achievement Domain results* for

campuses based on the percentage of economically disadvantaged (EcD) students enrolled at each campus.

(Please see Attachment A for a description of MCA’s methodology.) In Figures 1 and 2, the blue dots

represent campuses with less than 20% EcD students enrolled and the red dots represent campuses with

80-100% EcD students enrolled. The dotted line at 60 represents TEA’s published cut score for an “A.”

The cut score of 60, as TEA explains it, is intended to align the K-12 system with the Texas Higher

Education Coordinating Board’s “TX 60x30” plan; which states that by 2030, at least 60% of Texans ages

25-34 will have a certificate or degree.

*TEA’s methodology averages approaches, meets and masters grade level for all 2017 STAAR subjects.

Figures 1 and 2. Relatively few high-poverty elementary and middle schools would receive an ‘A’

for the Student Achievement Domain.

Graphs are based on 2017 TAPR data and TEA published methodology

3

.

Figure 1. Elementary Schools

3

TEA Accountability Policy Advisory Committee (APAC) materials, December 2017. At this time, the commissioner has not

made his final accountability decisions; therefore the methodology could change.

732 (or 17%) elementary school campuses = A

≈ 53% of the A’s enroll less than 20% EcD students

≈ 13% of the A’s enroll 60 –100% EcD students

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

3

Figure 2. Middle Schools

Sources: Graphs are based on 2017 TAPR data and TEA published methodology

3

.

The scatterplots shown above in figures 1 and 2 indicate that very few high-poverty elementary and middle

schools would receive an “A” for the Student Achievement Domain as it is currently defined, while a little

more than half of all low-poverty schools would receive an “A”.

Curious readers may ask, “Which high-poverty campuses (the yellow and red dots) are above the “A”-

line? To what practices do they attribute their results? Can other schools implement these same practices

to obtain similar outcomes?” By looking at the school names and total enrollment, we’ve learned that

most, but not all, of the few high-poverty campuses above the cut score of 60 are small campuses, each

with fewer than 500 enrolled students. Many have names that include the words “Magnet,” “G/T,”

“Montessori,” “STEM” or “STEAM,” “Young Men’s or Young Women’s Academy,” etc. From the

names, one can infer that these probably are high-performing, high-poverty specialty campuses, possibly

with selective enrollment criteria, rather than traditional, comprehensive neighborhood schools.

Elementary and middle schools only have STAAR results to use in the Student Achievement Domain

calculation. In contrast, statute requires the use of multiple data sources in the domain calculation for high

schools and districts: STAAR results; graduation rates; and College, Career, and Military Readiness

(CCMR) indicators. (TEC, §39.053(c)(1)(B).) The commissioner must decide how much to weight each

of these indicators in calculating the Student Achievement Domain score for high schools and districts.

Accountability advisory groups (e.g., ATAC and APAC) and other public school advocates strongly

recommend that TEA weight each high school indicator equally when calculating the Student

Achievement Domain score. However, if it is true that TEA will implement a single accountability system

to satisfy both state and federal accountability requirements, then it appears that TEA has declined to use

208 (or 13%) middle school campuses = A

≈ 60% of the A’s enroll less than 20% EcD students

≈ 5% of the A’s enroll 60 –100% EcD students

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

4

this recommendation. TEA’s revised ESSA plan

4

states that the indicators will be weighted as follows

to calculate the domain score: STAAR, 40%; CCMR, 40%; and Graduation Rates, 20%. Please see

Figure 3 to understand the potential impact of applying equal weights in the domain calculation.

Figure 3. Almost all high schools would receive an “A” when STAAR, CCMR, and Graduation

Rate indicators are weighted equally. Graphs are based on 2017 TAPR data, Index 4 PSR and TEA published

methodology

3

.

Figure 3. HS Option A: 34/33/33 grad rate

Graphs are based on 2017 TAPR data, Index 4 PSR and TEA published methodology

3

.

Figure 3 shows that almost all high schools, regardless of EcD enrollment, would receive an “A” when

STAAR, CCMR, and Graduation Rate indicators are weighted equally in the calculation of the Student

Achievement Domain score; and fewer high schools would receive “A” ratings if Graduation Rates were

to be weighted only 20% in the calculation (88% compared to 94%).

The absence of a clear explanation for the state’s decision to minimize graduation rates leads us to wonder

if TEA leadership is concerned about the appearance of having “too many” high schools earn “A” ratings

– eventhough the law clearly states that it should be mathematically possible for ALL campuses to earn

“A” ratings. The commissioner recently praised Texas’ public high schools for being among the top five

performers in the nation with regard to graduation rates.

5

Why, then, is this same indicator going to be

minimized in the state’s calculations?

Following are some recommendations for the commissioner, and for districts, to mitigate concerns about

the use of letter grades as ratings. Particular attention is given to potential limitations in the Student

Achievement Domain calculations, as they are defined in the commissioner’s current proposal.

4

TEA submitted the revised ESSA plan to USDE on January 8, 2018. More information about TX ESSA Plan can be found

here: https://tea.texas.gov/About_TEA/Laws_and_Rules/ESSA/Every_Student_Succeeds_Act/

5

Commissioner Morath, Jan. 24, 2018 in remarks to the appointed Texas Commission on Public School Finance. More

information about the commission can be found here https://tea.texas.gov/schoolfinancecommission/

94% HS campuses = A with equal weights applied

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

5

Recommendations to TEA

• The commissioner is urged to include non-test based indicators for elementary and middle schools to

promote fairness. Some examples include “enrichment” course completion rates for fine arts, physical

education, and second language acquisition, extra-curricular participation rates (UIL, clubs, etc.),

middle school dropout rates, and full-day Pre-K participation rates. Statute provides the commissioner

with authority to adopt indicators and standards at any time; exercising that authority would address

the entirely test-driven determination of the Student Achievement domain as is currently planned.

• The commissioner should accept the recommendations of practitioners by applying equal weights to

the STAAR, CCMR and graduation rate indicators in the evaluation of high schools and districts.

Doing so is 1) within the commissioner’s authority in current law, 2) consistent with the accolades

given to Texas public high schools for their exemplary graduation rates, and 3) renders “A” ratings

attainable for most high schools – which is aligned to specific direction to the commissioner in the

current law.

• The commissioner should phase in the Student Achievement Domain targets to 1) align with the ESSA

Academic Achievement Indicator (47-53-60), and 2) positively motivate continuous improvement.

The commissioner could begin with the statewide average of 47 as a reasonable initial target and

increase the target in 5-year increments, which also serves to balance the need for system stability with

the need for continuous academic improvement.

• The commissioner should expand the list of industry certifications to include CTE ‘coherent sequence

of course’ graduates and School-to-Workforce program graduates to recognize the achievement of

these graduates, too.

Recommendations to Districts

• District leadership should provide an appropriate interpretive framework when reporting Student

Achievement Domain scores in the new system. This will help stakeholders to understand that the

appearance of “lower” results is as much a function of the changes in state methodology, as it may be

of any changes in actual performance.

• Districts should adopt CTE coherent sequence of courses that lead to certifications in high-demand

fields in the workforce, primarily because that will serve students well.

• If a domain score of 60 is the adopted target to represent an “A” in the new system, then district and

campus leaders should anticipate some pushback from certain groups of people (e.g., “the system is

rigged to give everyone an ‘A,’” or “the standards have been lowered for schools - students would be

given ‘F’s’ for grades of 60)”. Factual information, provided in advance, may help to manage the

expectations of various stakeholder groups.

• District and campus leadership teams should ensure contextual understanding of the results. That is,

while the law requires it to be mathematically possible for all schools or districts to receive “A” ratings,

available data suggest that such ratings in the Student Achievement Domain are less likely to be

assigned to elementary and middle school campuses educating large percentages of economically

disadvantaged students, than to campuses with small percentages of these students.

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

6

SCHOOL PROGRESS DOMAIN

What We Know Now

Statute requires that the School Progress Domain indicators include:

“the percentage of students who met the standard for improvement, as

determined by the commissioner; and for evaluating relative

performance, the performance of districts and campuses compared to

similar districts or campuses.” (TEC, §39.053(c)(2)) In response, TEA

plans to implement two methods of gauging progress. The first method,

referred to here as Part A: Student Growth, measures whether the

students’ levels of proficiency change over time on STAAR reading

and mathematics. The second method, referred to here as Part B: Relative Performance, uses a regression

model to assign letter grades based on the relationship between the percentage of economically

disadvantaged students enrolled and Student Achievement Domain scores, relative to the relationship

observed for the entire state.

Using available 2017 Texas Academic Performance Report (TAPR) data and TEA’s published

methodology, MCA modeled campus and district results for Part B: Relative Performance in the new

School Progress Domain. The results indicate that this component of the new accountability system does

not appear to function with a similar negative bias for campuses that serve large percentages of

economically disadvantaged students, as was seen in MCA’s modeling of the Student Achievement

Domain. Potential issues in the School Progress domain instead stem from 1) the weights proposed for

use in calculating Part A: Student Growth and 2) the meaningfulness of the varying cut scores used to

assign letter grades in Part B: Relative Performance. Each of these potential issues is discussed next.

Part A: Student Growth awards points (0, 0.5 or 1 point) based on year-over-year changes in students’

proficiency levels on STAAR reading and mathematics tests (e.g., declined a level or more, stayed at the

same level, or increased a level, respectively). This proposed approach is a significant departure from past

accountability systems. From 1994 to 2011, the state’s academic accountability systems relied upon

changes in the percentages of students “passing” the state assessments, from one year to the next, as the

key metric. Changes in percent passing were considered to be indicative of growth or improvement in

performance. With implementation of the STAAR assessment program in 2012, the state began to

calculate individual-level year-over-year progress on STAAR reading and mathematics tests, and compare

those results to statistically expected performance. The amount of actual change then was classified as

having either met, exceeded, or not met the statistically expected growth. The new A-F system changes

the dynamic entirely. Not only does the new system shift to yet another growth metric calculation, the

system employs a weighting scheme that emphasizes growth toward postsecondary readiness – the highest

possible proficiency level – for all students regardless of their prior year proficiency level.

Three specific points of information are needed to anticipate how Part A: Student Growth might work in

the new accountability system. First, the commissioner needs to define how the system will distinguish

between “excellent performance” and “minimally acceptable performance.” Second, it is not clear whether

high schools can be evaluated for Student Growth with adequate reliability, given the limited availability

of pertinent data (particularly in mathematics). Third, the commissioner has not announced how letter

grades will be assigned to schools or districts on the Part A: Student Growth component of the School

Progress Domain. Until we gain clarity on these three points, it is impractical to model this component of

the School Progress domain.

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

7

Part B: Relative Performance uses a regression model to compare the relationships between Student

Achievement Domain scores and the percentages of economically disadvantaged (EcD) students enrolled

in schools or districts across the state. A trend line shows the statewide average relationship between the

two variables. Specific distances above and below the trend line are used to define various performance

‘bands’ that, in turn, determine the letter grade for the Relative Performance component. Therefore, a

campus with a relatively small percentage of enrolled EcD students must meet a higher Student

Achievement Domain score to receive an “A,” than does a campus with a very large percentage of enrolled

EcD students. Please see TEA’s graphical representation of Part B, Relative Performance, in Figure 4

below.

Figure 4. TEA Middle School Example

Source: TEA APAC Meeting December 4, 2017, page 18.

TEA’s most recently published cut scores show that the performance band for a Part B: Relative

Performance grade of “A” begins at a Student Achievement Domain score of 43 (for a high poverty middle

school) and reaches a maximum of 92 (for a low poverty high school), depending on the campus type and

percentage of EcD students enrolled.

6

On the one hand, the wide spread in the cut scores for the

assignment of an “A” rating seems reasonable given historical data showing large and persistent

performance disparities among EcD and Non-EcD students in Texas on state assessments. On the other,

a 40+ point span to earn the exact same letter grade risks confusion in the community and the media about

the meaningfulness of any given letter grade with regard to student learning and campus or district

effectiveness.

By applying TEA’s most recently published cut scores to the results of MCA’s Student Achievement

Domain models, the scatter plots below show the performance bands that could be used to assign letter

grades to the Part B: Relative Performance scores. Please see Figures 5 through 7, below.

6

TEA School Progress Look-Up Table, APAC, December 4. 2017. Additional information regarding the 2018 Accountability

Development materials can be found here https://tea.texas.gov/2018AccountabilityDevelopment/

. At this time, the

commissioner has not made his final accountability decisions; therefore the methodology and cut scores could change.

Part B: Relative Performance.

Using TEA’s regression model, a campus

with a small percentage of EcD students

enrolled must meet a higher standard to

receive an ‘A’ than does a campus with a

large percentage of EcD students enrolled.

>83

>43

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

8

Figures 5 – 7. “Mathematically possible” can mean “reasonably likely” for campuses educating

large percentages of economically disadvantaged students. Graphs are based on 2017 TAPR data and TEA

published methodology

6

.

Figure 5. Elementary Schools

Figure 6. Middle Schools

Most, but not all, of the high-performing, high-poverty middle and elementary schools

enroll fewer than 500 students and have names that include the words “Magnet,” “G/T,”

“Montessori,” “STEM” or “STEAM,” “Early College,” “Young Men’s” or “Young Women’s

Academies,” etc. From the names, one can infer that these are high-performing, high-poverty

specialty campuses, possibly with selective enrollment criteria, rather

than traditional,

comprehensive neighborhood schools.

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

9

Figure 7. HS Option B: 40/40/20 grad rate

Sour

ces: Graphs are based on 2017 TAPR data and TEA published methodology

6

.

Thus, in contrast to the model of the Student Achievement Domain, It appears that “mathematically

possible” for any or all schools or districts to receive an “A” rating can mean “reasonably likely”,

regardless of the percentages of economically disadvantaged students being served.

The results of MCA’s modeling affirm the possibility that, among high schools in particular, exemplars

with high performance and large percentages of economically disadvantaged students abound. The data

displays also give rise to some questions. For example, why are the performance bands so tightly “packed”

at the middle school level, when contrasted with those at the elementary and/or high school levels? How

instructionally meaningful are the differences in performance at the “C” versus “B” letter grades, or

perhaps more importantly, at the “C” versus “D” letter grades, since sanctions commence with “D” letter

grades? And, do these results in any way shed light on how educational practices must change for all

schools to become “high performers,” regardless of the characteristics of their respective student

populations? These questions go to the heart of the new accountability system’s ability to meaningfully

discriminate between performances for purposes of assigning letter grades (i.e., validity and reliability),

and the system’s utility in informing improvements in instruction. It is difficult to accept the premise

that accountability is intended to drive systemic improvement, if the system can neither consistently and

meaningfully classify performance as acceptable or unacceptable, nor inform practitioners about what,

and how, specific instructional behaviors need to change.

Recommendations to TEA

• The commissioner should elect to assign letter grades to the School Progress Domain results by

selecting the best outcome between the Part A: Student Growth and Part B: Relative Performance

components. This will serve to promote fairness by reducing the risk of incorrectly identifying

campuses or districts as having unacceptable levels of performance, particularly during the earliest

years of implementation of the new system. This approach to the assignment of domain grades also

may temper some of the anticipated rhetoric about “How come that district got an “A” when my district

has a higher score on the exact same component?” The commissioner can revisit this decision once a

stable baseline of complete information is established.

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

10

• To promote fairness and validity of the accountability system, the commissioner is urged to continue

Agency research into a more accurate measure (or measures) of educational need or educational

‘degree of difficulty’ than continuing to use participation in the Free / Reduced-Price Meals (FRPM)

program as the statistical proxy for educational disadvantage.

o The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), National Forum on Education Statistics

calls on the education community to “adopt and implement alternative SES measures that may

more accurately identify individual students who are socioeconomically in need.”

7

This call

to action is made based on the fact that the FRPM indicator is becoming progressively less

suitable as a proxy for an individual student or family’s socioeconomic status due to three

primary factors:

1. “Interpretation and use in a manner not intended by the collection: FRP eligibility is

being used as a proxy for SES even though it only reflects income (or, in some cases,

school-wide characteristics) rather than other components of SES that are widely

acknowledged to be relevant at the individual level, such as parent/guardian occupation

and education.”

2. “Severely limited access within the education community: FRP eligibility data at the

individual level are available only for the purposes of administering the meals program.

NSLP prohibits other education staff from using the data to determine the instructional and

non-instructional (service eligibility) needs of individual students.” [MCA note: Access has

not been severely limited in Texas.]

3. “Decreasing applicability as a measure of economic need: CEP is expected to improve

the efficiency and effectiveness of the NSLP meals program; however, it will also result in

the loss of individual student-level FRP eligibility data in participating education agencies.

Because many education agencies rely on FRP eligibility as a measure of SES, this change

would have serious implications on the quality of the SES proxy in LEA, SEA, and ED

data systems.”

Recommendations to Districts

• District and campus leadership must consistently communicate the message that every student must

demonstrate growth. How does the district intend to address instructional improvement so that student

academic growth is both universal and substantive?

• Districts must determine how to more rapidly identify and effectively serve students to keep from

perpetuating what the accountability system sees as “failures” – especially when growth actually is

occurring. The “school-dependent” student who starts the year behind grade level must experience

accelerated growth to meet or exceed grade level standards by the end of the school year.

• As with the Student Achievement Domain, district and campus leaders should provide an interpretive

framework to consumers of the ratings – parents, community and business leaders, the media, et al. –

so that they understand up front that the Relative Performance score associated with an “A” rating can

vary widely, i.e., from a 43 to a 92. Arguments over “they got an ‘A’ for the exact same score as we

did, but we only got a ‘B,’” and so forth, distract from the much more important conversation around

the question of, “what are WE going to do about this?”.

• District and campus leaders should work to ensure contextual understanding of the results.

Comparisons of current results for one’s own district or school to: 1) historical data prepared using the

same methods (when possible), 2) “like” districts or schools and 3) statewide results may help to

ground the outcomes for consumers.

7

National Forum on Educational Statistics: Forum Guide to Alternative Measures of Socioeconomic Status in Education Data

Systems, page 6. The complete guide is found here https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2015/2015158.pdf

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

11

CLOSING THE GAPS DOMAIN (and ESSA DOMAIN)

What We Know Now

According to TEA’s most recent plan to implement the Every Student

Succeeds Act (ESSA), the Closing the Gaps Domain letter grade is

determined by the percentage of student groups that meet or exceed

state-identified achievement targets.

8

Large, diverse campuses may

have more than 70 achievement targets to meet. Individual students’

results are used multiple times in the domain evaluation. TEA models

show that most campuses will meet less than half of their applicable

achievement targets. And the Closing the Gaps Domain score

comprises 30% of the overall letter grade rating.

HB 22 codified that the Closing the Gaps Domain include: “the use of disaggregated data to demonstrate

the differentials among students from different racial and ethnic groups, socioeconomic backgrounds, and

other factors, including: (A) students formerly receiving special education services; B) students

continuously enrolled; and (C) students who are mobile. (TEC, §39.053(c)(3)) While the statutory

language is broad, Commissioner Morath has been clear in his intent to align the state and federal

accountability systems in the Closing the Gaps Domain. Many educators and parents remember the days

when “Adequate Yearly Progress” (AYP) determinations, under the federal No Child Left Behind act,

were not aligned with the state accountability system. As a result, it was possible for apparent

“mismatches” in ratings to occur. A campus rated as “Recognized” by the state could, for the very same

school year, be identified as having “Missed AYP.” The resulting dissonance was difficult to explain and

raised doubts about the credibility of both the state and federal accountability ratings systems.

As shown in the 2018 Closing the Gaps Domain Status Report

9

the following elements are included in the

letter grade calculation for this domain:

• 14 Student Groups

• 5 Groups of Achievement Indicators [these are identical to the ESSA-required indicators]:

− Academic Achievement in Reading and Mathematics, as determined by the “Meets Grade

Level” standards on STAAR

− Growth in Reading and Mathematics (Elementary and Middle Schools), as determined by the

“Meets Growth” standard on STAAR

− Graduation Rates (High Schools, K-12, Districts), as determined by federally compliant

calculations (no state-required records exclusions are applied)

− English Language Proficiency (ELP), as determined by levels achieved on TELPAS

− School Quality or Student Success:

Student Achievement Domain Performance for Elementary and Middle Schools as

determined by combining Approaches Grade Level, Meets Grade Level, and Masters

Grade Level performance on STAAR in Reading, Mathematics, Writing, Science, and

Social Studies

8

TEA submitted the revised ESSA plan to USDE on January 8, 2018. More information about TX ESSA Plan can be found

here: https://tea.texas.gov/About_TEA/Laws_and_Rules/ESSA/Every_Student_Succeeds_Act/

9

Appendix F of the revised ESSA plan

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

12

College, Career, and Military Readiness Performance (High Schools, K-12, and

Districts), as calculated for the relevant Student Achievement Domain CCMR

indicators

• Results compared to Achievement Indicator Goals or Targets (both long-term and 5-year interim),

as established in the state’s ESSA plan

10

• Test participation rates for all students and each student group compared to 95% targets for

participation in STAAR Reading and Mathematics, as required by ESSA

While having this many indicator targets to meet in a single domain seems rather daunting on its face, it

also appears to be fundamentally unfair to large, diverse campuses and districts; which will have 25 or

more students in most, if not all, of the student group categories. TEA’s model from the December APAC

meeting demonstrate that there is good reason to be concerned: the model shows that not very many

campuses will meet all of their indicator targets by this coming August. Please see Figure 8, below.

Figure 8. TEA Data Modeling

Source: TEA APAC Meeting December 4, 2017, page 21.

Recommendations to TEA

• The commissioner should elect to use the performance results of Title I campuses to set the baseline

targets, rather than using the results of ALL campuses (both Title I and Non-Title I) as is currently

proposed.

• To promote fairness in this domain calculation, the commissioner is urged to expand the idea of

satisfying targets in either Student Achievement OR School Progress indicators. Texas’ proposed

ESSA plan has two categorical calculations for achievement (Academic Achievement and School

Quality) and only one category for growth. The commissioner is urged to expand the ESSA plan to

include additional, non-test-based measures in accountability evaluations. For example, the state

should consider using chronic absenteeism (like 33 other states’ plans do) or a statewide climate survey

(like 10 other states’ plans do) for the School Quality / Student Success Indicator, rather than yet

another variation of STAAR results. Large, diverse elementary and middle school campuses could

have over 70 achievement targets to meet in the Closing the Gaps domain, and high schools appear to

10

Appendix A of the revised ESSA plan displays both the long-term and short-term targets

High schools, whose indicators

include CCMRs, graduation rates,

TELPAS, and STAAR, are found

to meet more of their achievement

indicators than do elementary and

middle schools, whose Closing the

Gaps D

omain score is almost

exclusively based on STAAR tests.

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

13

have an advantage over elementary and middle schools because non-STAAR based measures are

included in their evaluations.

• It is essential that the commissioner introduce some “checks and balances” in the federal accountability

evaluations, given the large number of targets that schools and districts must meet. Therefore, in its

final ESSA plan, TEA should include the use of an improvement mechanism as a way for “D”-rated

schools and districts to achieve a passing letter grade.

Recommendations to Districts

• Just as was true under NCLB, the state’s ESSA plan makes it clear that individual students’ results are

going to be used multiple times in the evaluation of this domain. District leadership should ensure

contextual understanding that poor achievement by a small number of individuals may affect multiple

targets for a given school or district.

• The proposed TEA model inadequately recognizes the complex challenges posed by poverty in

education, because of its use of F/RPM participation as a proxy for educational disadvantage. District

and campus leadership teams should be prepared to showcase all of the ways in which they are creating

and maintaining support systems for the success of all students. The expectations and targets are

equally high for all students. What the proposed accountability system fails to recognize is the wide

variation in intensity of effort that may be required to help all students attain or surpass those

expectations and targets.

We agree with those who believe that letter grades will not measure all of the great things we do everyday

in public education. And we will continue to advocate for a fair and meaningful accountability system.

The commissioner has not issued his final accountability decisions and TEA continues to accept feedback

on the development of the A-F system. What recommendations do you have to improve the proposed

system? Send your comments to feedbackAF@tea.texas.gov.

Questions about this MCA opinion article? Please send questions to dcarney@moakcasey.com.

© Moak, Casey & Associates, February 2018

14

Appendix A

Moak, Casey Model Methodology for Student Achievement and School

Progress Domains

Data Sources: 2017 TAPR Download, 2017 Accountability Download

STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT DOMAIN

Calculate the STAAR score.

1. Using the numerators and denominators from the 2017 TAPR download, the values for Reading, Math,

Science, Social Studies, and Writing for All Students are used to calculate the percentage of tests meeting

the standard as follows: Tests Meeting Standard divided by Tests Taken (R+M+S+SS+W) / (R+M+S+SS+W).

2. This is repeated for Approaches Grade Level, Meets Grade Level, and Masters Grade Level.

3. The 3 levels (Approaches, Meets, and Masters) are added together and then divided by 3 to create the

average of the 3 levels, or the STAAR score. (The final STAAR score is rounded).

Limitations: Some numerators and denominators are masked in the download file due to small numbers.

These absent numbers were ignored during the calculations, and so the percentages for Approaches, Meets,

and Masters Grade Level may not match the 2017 TAPR exactly. TAPR percentages were not used because the

2017 TAPR Meets Grade Level percentages are for 2 or more subjects (not all subjects). Differences will be

more observable in districts/campuses with smaller enrollments.

College, Career, and Military Readiness (CCMR) score.

Due to the unavailability of many of the indicators in the proposed CCMR score, the 2017 Index 4 CCR measure

was used as a proxy from the 2017 Accountability download.

Graduation Rate score.

The 4-year graduation rate and the 5-year graduation rate for All Students are taken from the 2017 Accountability

download. The higher of the 2 graduation rates is used.

Overall Student Achievement Score.

For elementary and middle or junior high schools, the STAAR score is the Student Achievement Domain score. For

high schools and districts, which include STAAR, CCMR, and Graduation Rates, we elected to use Option B as

described in the December 2017 APAC document: STAAR score – 40%, CCMR score – 40%, and Graduation rate

score – 20%. For campuses, with no graduation rate, the weight is distributed equally between the STAAR score

and the CCMR score (50%-50%). If there is no CCMR score, then only the STAAR score is used. Alternative

Education campuses/districts and campuses/districts with no significant data are not included.

SCHOOL PROGRESS DOMAIN Part B: Relative Performance

The same overall score used for the Student Achievement Domain is used for School Progress, but a

school/district’s Economically Disadvantaged Enrollment is taken into consideration. The sample chart on page

17 of the Accountability Policy Advisory Committee (APAC – Dec. 2017) HB 22 Domain Models document was used

to assign the letter grades in this domain.