Entrepreneurship

in the Middle East

and North Africa:

How investors

can support and

enable growth

By

Ahmad J. Alkasmi

Omar El Hamamsy

Luay Khoury

Abdur-Rahim Syed

Entrepreneurship

in the Middle East

and North Africa:

How investors

can support and

enable growth

The Middle East and North Africa region is on the cusp of a potential

entrepreneurship gold rush. Public and private investors that follow

six best practices will be poised to support and enable the growth of

the region’s burgeoning start-up ecosystem.

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

5

1. Executive summary

2. MENA has high, but mostly untapped, entrepreneurship potential

3. Digital entrepreneurship is beginning to thrive in MENA

3.1 E-commerce

3.2 Digital music

3.3 Last-mile delivery and logistics

3.4 Fintech

3.5 Travel

4. The MENA venture capital ecosystem to support entrepreneurship

is flourishing

4.1 Corporate venture capital is becoming increasingly relevant

4.2 Government-led initiatives are focusing on ecosystem growth

4.3 Exits are a key challenge in the region

5. Six best practices for start-up ecosystems players to turbo-charge MENA

entrepreneurship

5.1 Develop robust investment theses leveraging local context

5.2 Capture and proactively engineer network effects

5.3 Invest at scale

5.4 Invest and manage performance with a patient, programmatic growth mind-set

5.5 Secure investment independence in governance, to win right talent

5.6 Monitor KPIs in line with value creation model

6. Conclusion

7. About the authors

06

09

15

15

15

16

16

18

21

22

24

26

29

29

29

31

32

33

34

36

37

Contents

6

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

1

For the purposes of this report, we rely on the World Bank’s definition of the Middle East and North Africa

(MENA) region: Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman,

Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, the West Bank and Gaza, and Yemen. (“Middle

East and North Africa,” World Bank, accessed March 20, 2018, worldbank.org.) The research assembled for

this report draws from various sources that may define the region slightly differently.

2

The Mobile Economy, Middle East and North Africa, GSMA 2016, GSMA Intelligence, Wearesocial.com.

3

“Media use in the Middle East 2017: A seven-nation survey,” Northwestern University in Qatar, 2017,

mideastmedia.org.

4

John McKenna, “The Middle East’s start-up scene explained in five charts,” World Economic Forum, May 17,

2017, weforum.org.

5

Enrico Benni, Tarek Elmasry, Jigar Parel, and Jan Peter aus dem Moore, Digital Middle East: Transforming the

region into a leading digital economy, October 2016, McKinsey.com.

6

MAGNiTT interviews conducted March 2017

7

The state of digital investments in MENA: 2013–2016, a joint report from ArabNet and Dubai SME, sme.ae.

1. Executive summary

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is one of the most digitally connected

in the world:

1

across countries, an average of 88 percent of the population is online daily,

and 94 percent of the population owns a smartphone.

2

Digital consumption is similarly

high in some countries; for example, Saudi Arabia ranks seventh globally in social media

engagement, with an average of seven accounts per individual.

3

However, despite this sizable appetite for online content and services, key digital sectors

remain nascent, and entrepreneurship potential is yet to be fully tapped. Across MENA,

only 8 percent of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have an online presence—ten times

less than in the United States—and only 1.5 percent of MENA’s retail sales are online, five

times less than in the United States.

4

Research by Digital McKinsey suggests that the Middle

East has only realized 8 percent of its overall digital potential, compared with 15 percent in

Western Europe and 18 percent in the United States.

5

However, we believe the region is at the start of a new s-curve: MENA is experiencing a

startling growth in both the number of successful start-ups and the amount of investment

funding available to them. From digital music to digital logistics, start-ups are scaling by

adapting offerings and business models to serve local needs. Examples of this abound, from

Fetchr’s use of GPS technology to power delivery in a region with few addresses, to Fawry’s

local network of retailers that anchors its payments network and overcomes barriers in the

fintech space.

Moreover, the number of investors in the region increased by 30 percent from 2015 to 2017,

while total funding increased by over 100 percent in the same period.

6

Corporate venture

capital funds (CVCs) in particular are rapidly emerging in the evolving MENA investment

ecosystem. In 2015 and 2016, 14 new, significant CVCs entered the MENA market. Corporate

VC assets under management (AUM) grew by over 2.4 times from 2012 to 2016, reaching 20

percent of total venture capital (VC) AUM in the region.

7

Furthermore, from targeted, VC-like investment funds to structured incubator and

accelerator programs, public institutions are also playing an increasingly key role in the

start-up ecosystem. Recent examples include the establishment of Fintech Factory in Egypt,

Fintech Hive in the United Arab Emirates, and National Fund for SME Development

in Kuwait.

71. Executive summary

Overall, the ecosystem supporting the growth of MENA’s start-up landscape has been

falling into place. However, distinct gaps remain for investors in properly identifying

potential in new business models, and in scaling chosen start-ups. We recommend investors

in the start-up space adopt six best practices to unlock the potential of entrepreneurship in

the MENA region:

Develop robust investment theses leveraging local context

Capture and proactively engineer network effects

Invest at scale

Manage performance with a patient, programmatic growth mind-set

Secure investment independence in governance, to win the right talent

Monitor KPIs in line with the value creation model

Local entrepreneurs have demonstrated they can be innovative and bold to meet changing

demand. With the appropriate adoption of best practices in venture investing, significant

value can be created for investors, promising new businesses, and for the entrepreneurship

ecosystem in the region.

8

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

9Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

2. MENA has high, but mostly

untapped, entrepreneurship potential

MENA’s digital future is bright. Entrepreneurship is a key engine of economic growth

and innovation. A 2016 report on the Middle East’s economic recovery and revitalization

highlighted the impact of entrepreneurship’s “multiplier effect” on an economy. The report

noted that for every ten successful new enterprises, nearly $1.5 billion in new valuations and

more than 2,500 jobs are directly created.

8

Undergoing a period of great social, political, and economic transformation, the Middle

East and North Africa (MENA) region is becoming a burgeoning hub of commercial

innovation and entrepreneurship. Home to a population of more than 430 million people

across its constituents and with a GDP of USD $2.8 trillion,

9

the states across the region are

experiencing a new wave of economic activity, and their digital future looks even brighter.

MENA is projected to exhibit real GDP growth in the coming years, reaching $3.4 trillion

in GDP value by 2020; however, the region has in fact realized only 8.4 percent of its digital

potential.

10

This growth potential has been attributed to many factors, including the region’s large,

youthful population. Currently, approximately 60 percent of the overall MENA population

is under the age of 30, while 30 percent falls within the 15–29 age bracket.

11

We expect these

young people to fuel the rapid expansion of the digital sector in the coming years.

A second powerful variable, dramatically interacting with the comparatively young

population, is the region’s rapidly increasing access to technology as well as its propensity

for digital adoption and consumption. Today, 88 percent of the Middle East’s population

are online daily; 94 percent own a smartphone device, on which they spend an average of

three hours on mobile daily; and 38 percent of the population are active social media users.

Moreover, in 2016 alone, the number of active social media users increased by 47 percent.

12

However, as smartphone penetration rates have spiked in certain countries—namely Gulf

Cooperation Council countries—they have remained far lower in others. Kuwait, Saudi

Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) boast even higher penetration than the United

States. At the other end of the spectrum, Algeria, Egypt, and Morocco stand in stark contrast

with far lower penetration (Exhibit 1). This diversity signals a deep underlying heterogeneity

across the region’s digital economy—another key driver of the untapped growth potential.

8

“Entrepreneurship in the Middle East: The time is now,” Endeavor Insight, June 29, 2016,

ecosysteminsights.org.

9

The World Bank DataBank, Middle East & North Africa data, accessed December 2017, data.worldbank.org;

“Regional economic outlook: Middle East and Central Asia,” International Monetary Fund, October 2017,

imf.org.

10

The IMF Data Mapper, International Monetary Fund, December 2017, imf.org; Enrico Benni, Tarek Elmasry,

Jigar Parel, and Jan Peter aus dem Moore, Digital Middle East: Transforming the region into a leading digital

economy, October 2016, McKinsey.com.

11

Arab human development report 2016: Youth and the prospects for human development in a changing reality,

United Nations Development Program (UNDP), 2016, arabstates.undp.org.

12

The Mobile Economy, Middle East and North Africa, GSMA 2016, GSMA Intelligence, Wearesocial.com.

10

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

Exhibit 1:

Mobile phone penetration, 2010-2022E

200

160

120

100

80

2016 2019 2020

60

140

180

2017 2018 2022

220

240

2013 2015201220112010 2014 2021

Iraq

Iran

Tunisia

Saudi Arabia

Qatar

UAEOmanKuwait

Egypt

Algeria

Morocco

Penetration,

%

Year

SOURCE: Mason DataHub

As smartphone penetration and online accessibility have increased in some countries, so too

has digital demand—which is therefore disproportionately high in those countries compared

with those with lower penetration. As consumers increasingly get online through improved

3G/4G data access and reach (Exhibit 2), greater hunger for online content and services has

followed.

Take Saudi Arabia, for example. The country ranked seventh globally by number of

individual accounts on social media in 2017, with an average of seven accounts for each

individual.

13

It also ranked first among MENA countries in Twitter and YouTube usage in

2017.

14

The number of Instagram users in Saudi Arabia grew sixfold from 2016 to 2018, to

13 million from 2.1 million,

15

and the country’s Snapchat penetration grew from 24 percent

in 2014 to 74 percent in 2016—while the global average moved from 12 percent to just 23

percent.

16

Of course, Saudi Arabia is not alone. According to Ericsson, smartphone data consumption

across MENA will increase from 1.8 GB in 2016 to 13 GB in 2022.

17

13

“Media use in the Middle East 2017: A seven-nation survey,” Northwestern University in Qatar, 2017,

mideastmedia.org.

14

“Media use in the Middle East 2017.”

15

“Media use in the Middle East 2017.”

16

Damian Radcliffe, Social media in the Middle East: The story of 2016, December 2016, academia.edu.

17

Naushad K. Cherrayil, “Video consumption in UAE, Saudi Arabia exceeds global average,” Gulf News,

November 23, 2016, gulfnews.com.

112. MENA has high, but mostly untapped, entrepreneurship potential

18

John McKenna, “The Middle East’s start-up scene explained in five charts,” World Economic Forum, May 17,

2017, weforum.org.

19

Enrico Benni, Tarek Elmasry, Jigar Parel, and Jan Peter aus dem Moore, Digital Middle East: Transforming the

region into a leading digital economy, October 2016, McKinsey.com.

Exhibit 2:

Growth in smartphones, broadband and 3G/4G usage

Smartphone penetration and mobile

broadband subscriptions, %

3G/4G network migration across MENA from

2010 to 2020, % of connections

90

95

99

61

95

89

31

42

77

85

UAE

Saudi

Arabia

Lebanon

Egypt

Qatar

90

85

81

77

71

62

56

51

46

42

39

19

23

28

36

39

41

43

45

46

8

11

13

16

15

10

2

15

5

16 19181714

1

13112010 12 2020

Mobile broadband subscriptions

Smartphone penetration

2G4G

3G

SOURCE: The Mobile Economy, Middle East and North Africa, GSMA 2016, GSMA Intelligence, Economic Forum 2015,

Network readiness index

However, despite this sizable appetite for online content and services, key digital sectors are

still nascent. E-commerce, for example, has significant potential for further growth. Across

MENA, only 8 percent of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have an online presence—

ten times less than in the United States. Moreover, only 1.5 percent of MENA’s retail sales are

online, five times less than in the United States.

18

Beyond e-commerce, untapped digital potential throughout the region is a common theme.

Research by Digital McKinsey suggests that the Middle East has only realized 8 percent of

its overall digital potential, compared with 15 percent in Western Europe and 18 percent in

the United States. In fact, the region stands poised to unlock an additional $95 billion per

year to its annual GDP through the digital economy if it reached the levels of global leaders.

19

Moreover, global players rather than regional ones are capturing the bulk of the digital value

being created. Digital giants such as Facebook and Google, and enterprise IT behemoths

such as IBM and Microsoft, remain the leading players catering to local demand.

12

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

Relative to global GDP contribution, local digital markets are just a fraction of their

potential size (Exhibit 3). This is costing local champions significantly; in e-commerce

alone, more than 80 percent of local spending goes to global suppliers and service providers

as global giants enter the market through acquisitions, joint ventures, or their own direct

entry into the markets. The situation is similar in digital payments, where local players have

left 70 percent on the table. In a market where the global transaction value in online, mobile,

and contactless payments increased 20 percent from 2015 to 2016, reaching $3.6 trillion in

value, there is significant room for local players to capture a greater share.

Exhibit 3:

MENA has lost revenue potential for local champions

1

100% = Global market revenues * (MENA's GDP/Global GDP) per sector

2

Actual MENA market size as a % of potential market; lost revenue potential due to revenues that are captured by international

players or untapped

SOURCE: Various sources (Gartner, Magna global, 451 Research)

Revenue pools are being captured by global players instead of local champions

MENA revenue

potential

(%)

1

Actual MENA

revenue share

2

(%)

Digital payments Digital gaming E-commerce

30%

17%

45%

100%100% 100%

Across the Middle East, the digital economy’s contribution to GDP is generally low compared

with other regions, at just 4.1 percent—half that of the United States (Exhibit 4). There is

again variance at the country level; for example, Bahrain’s digital contribution to GDP,

which is driven by digital exports, is akin to that of the United States.

13

Exhibit 4:

Share of digital contribution to GDP, %

0.4

0.9

3.8

4.3

4.4

5.1

8.0

4.1

6.2

8.0

United

States

Middle

East

Bahrain United

Arab

Emirates

Oman QatarKuwait Egypt Saudi

Arabia

Europe

SOURCE: Euromonitor Passport, September 2016; IDC ICT Black Book, September 2016; World Industry Services Database,

September 2016; UN data; World Development Indicators, World Bank, September 2016; Magna 2015; UNCTAD

stats 2011-2015; McKinsey analysis

Digital contribution as a share of GDP, estimates

In sum, MENA’s digital economy has seen and will see even more significant growth and

disruptions. These changes will be propelled by the region’s shift away from oil-based

economies toward more service-oriented industries with a strong digital presence; the

demographic shift to a younger, tech-savvy population; and the exponential evolution of

technology and channels.

However, for MENA to unlock the untapped entrepreneurship potential associated with

the digital economy, crucial questions remain: Will the high smartphone penetration rates

in some countries spread to the rest of the region to facilitate online accessibility? Will the

region succeed in enabling the growth of key digital sectors, such as e-commerce? Will local

entrepreneurs successfully capitalize on the regional digital demand? Fortunately, native

successes such as Careem, a ride-hailing app company based in Dubai, suggest that indeed,

regionally specific digital services can exist and can even flourish, despite the formidable

global competition of giants such as Uber.

2. MENA has high, but mostly untapped, entrepreneurship potential

14

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

15Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

3. Digital entrepreneurship is

beginning to thrive in MENA

Across digital spaces, a generation of local MENA start-ups have emerged and gained a

foothold throughout the value chains of various sectors. Five examples—e-commerce,

digital music, last-mile delivery and logistics, fintech, and travel—illustrate the growth of

local digital entrepreneurship.

3.1 E-commerce

Within e-commerce, the most mature digital sector in MENA, a variety of entrepreneurial

solutions have emerged—from pure-play marketplaces, such as Dubizzle in Dubai, that offer

a diverse array of sellers a platform to sell their goods, to full-fledged e-retailers, such as

Namshi, that offer digital storefronts, payment facilities, and delivery solutions (Exhibit

5). Moreover, hybrid models, such as Amazon’s Souq.com, have thrived offering both

marketplace and e-retail offerings.

Exhibit 5:

E-commerce sector offers a variety of solutions across the value chain – it is the

most mature yet still sub-scale

NOT EXHAUSTIVE

E-retailers

Market-

places

Hybrid

model

(market-

place &

e-retailer)

Platform

1

Currently few marketplaces

rely purely on customer-to-

customer sales

Platform

1

Starting as e-retailers, many

companies have developed

hybrid models to offer more

products to customers

Platform

1

Most e-retailers have

started to offer hybrid

model to customers

Integrated

2

Scant examples of inte-

grated marketplaces (e.g.

JadoPado acquired in 2017)

Integrated

2

So far, only two major inte-

grated players with sufficient

scale to dominate the

marketplace

Integrated

2

Some e-retailers have

started to offer payment

and delivery options

Attract

customers

Run the

store

Process

payments

Deliver

products

Engage &

care

Value chain

3

Local characteristics

1 Platform describes the internet platform without any integrated services (e.g. logistics or payment processing)

2 Integrated describes a company that is integrated along the value chain (e.g. ebay also has their own payment processor)

3 Assumption according to current plans for Noon

SOURCE: Publicly available information, team analysis

3.2 Digital music

Based in Lebanon, Anghami, the region’s largest local music-streaming service, launched in

2012 and provides unlimited streaming access to Arabic and international music. As of early

2017, the service’s 30 million users streamed 500 million songs a month.

20

The company has

flourished, with revenues in range of $20 million in 2017,

21

despite fierce competition from

20

Carolina Valladeres, “How we started the Arab world’s biggest music service,” January 30, 2017, bbc.com;

Samuel Wendel, “Meet the Lebanese entrepreneurs who built Anghami, the largest Arabic music streaming

app,” Forbes Middle East, March 9, 2017, forbesmiddleeast.com.

21

“Anghami, a million-dollar venture in tune with the region,” National, July 15, 2017, thenational.ae.

16

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

the likes of global players Apple Music and Spotify. Anghami also recently entered a new

direct licensing deal with Warner Music Group to bring the group’s catalog of music to

the region.

22

The company generates 65 percent of its revenue through paid subscriptions, which have

grown 300 percent year over year.

23

Anghami has built an innovative offering that caters

directly to local tastes; for example, it has Arabic language functionality across its platform,

exclusive deals with the region’s largest artists, and several partnerships with local media

and telecom networks. The company is also mobile-first, with 95 percent of its consumption

occurring on mobile devices. As the region’s access to 3G and 4G data is expected to double

between 2015 and 2020, the music streaming user base will also increase, leading to

significant room for further growth of Anghami and similar services.

3.3 Last-mile delivery and logistics

As many consumers in MENA lack traditional home addresses, last-mile delivery can be

a costly and time-consuming exercise. Fetchr, a Dubai-based company, uses smartphone

GPS technology to accurately locate users for package delivery. Fetchr and other similar

services, such as what3words, offer solutions catered to developing markets by overcoming

contextual infrastructure barriers. As industries such as e-commerce continue to grow

rapidly in the region, solutions that address infrastructural shortcomings will prosper from

complementary effects. Global investors have begun to understand this concept, highlighted

by Fetchr’s recent $41 million Series B financing round.

24

3.4 Fintech

According to Payfort, a Dubai-based payment processing company owned by Amazon, the

region saw a 23 percent increase in online payments even back in 2015—suggesting the

fintech space is growing quickly, particularly in leading countries such as Saudi Arabia,

which exhibited year-on-year growth of 40 percent.

25

In this context, and enabled by the

growth in e-commerce, locally owned digital payments start-ups have sprung up across

the region.

22

“Warner Music Group and Anghami enter long term direct deal to provide music to the Middle East and North

Africa,” Warner Music Group, November 15, 2017, wmg.com.

23

Robert Elder, “Meet Anghami, the Spotify of the Middle East,” Business Insider France, August 31, 2016,

businessinsider.fr.

24

“Fetchr secures $41 million in Series B funding led by new enterprise associates, to continue disrupting the

traditional delivery industry,” Business Wire, May 16, 2017, businesswire.com.

25

“Arab world could see US$69 billion in online payment transactions per annum by 2020,” Payfort, June 2,

2016, payfort.com.

173. Digital entrepreneurship is beginning to thrive in MENA

Exhibit 6:

Fintech activities are intensifying

$50mn Investments in 2017

2X The increase in fintech investments up to 2016 but still <1% of global investments

105 Fintech start-ups in 2015 up from 30 in 2011

50–60% Compound annual growth rate for UAE fintechs over 4 years up to 2016

Rise of accelerators and funds

Fintech Hive

at DIFC

Fintech Factory

by Payfort

Fintech VC fund

and accelerator

Change in regulations

RegLab: First fintech regulatory

framework and sandbox

Sandbox and licenses

for nonbanks

SOURCE: “State of Fintech”, A report by Wamda and Payfort (URL accessed December 2017:

https://www.difc.ae/files/3614/9734/3956/fintech-mena-unbundling-financial-services-industry.pdf) “Startup fever: MENA exits

reach $3 billion over five years”, MAGNiTT Blog (URL accessed January 2018: https://www.magnitt.com/startup-fever-mena-exits-

reach-3-billion-over-five-years)

For example, Fawry, launched in 2010, is an Egypt-based, multichannel digital payment

platform that enables customers to transfer money without the need for a bank account. It

operates in more than 65,000 locations and has a presence across a multitude of channels

including online, ATMs, mobile wallets, and brick-and-mortar retail stores. Fawry has used

its local knowledge and network to build partnerships with several retailers, including a

range of small businesses such as groceries, pharmacies, and post offices. Each partner is

equipped with adapted point-of-sale machines—advances notoriously difficult to make for a

non-local company. Fawry claims more than 20 million customers, performs more than 1.5

million financial transactions daily, and processes $113.2 million annually in payments.

26

As connectivity grows in the region and smartphone penetration increases further, the

payments market is poised to grow rapidly, with Fawry in prime position to gain even

more ground.

Payfort (now an Amazon company post acquisition) has grown into one of the leading

payment platforms in the Arab world. It claims a wide array of partners, including Jumbo

Electronics, talabat.com, and Air Arabia. It has regularly updated its offering to cater to

specific segments; in 2015, it acquired White Payments to fast-track the online payment

options of start-ups and small businesses. At the same time, it has successfully delivered

broader innovative products and services, such as the recent card-on-delivery for UAE

customers and merchants.

27

26

“Fawry in numbers,” accessed in December 2017, fawry.com.

27

“PayFort rolls on card-on-delivery service for customers and merchants in UAE,” The Paypers, May 9, 2017,

thepaypers.com; Tamara Pupic, “PAYFORT acquires Dubai-based start-up,” Arabian Business, June 30, 2015,

arabianbusiness.com.

18

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

PayTabs, a Saudi alternative payment solution gateway with a head operations office in

Bahrain, has placed a strong emphasis on fraud prevention in e-commerce transactions.

PayTabs helps its clients reduce the payment bottleneck from e-commerce transactions and

provides more than 130 alternative payment options. It has gained a strong foothold in the

market: in 2017, the company raised $20 million in financing to facilitate its expansion to 20

markets in MENA, Africa, Europe, India, and Southeast Asia.

28

3.5 Travel

Wego is MENA’s largest travel search engine. Founded in Singapore in 2005, Wego has

grown to generate more than $1.5 billion per month in booking referrals to its various

partners. Initially the company focused on local preferences, with a strong emphasis on

being mobile-friendly and using its network to build partnerships with local travel agents,

airlines, and hotels. It has since invested in innovative solutions, such as its progressive web

app, which has led to an increase of 35 percent in average time spent on its iOS app, and the

use of advanced analytics to better target customers.

29

In August 2017, MBC (MENA’s largest multimedia company) invested in Wego through a

deal worth $12 million.

30

This strategic partnership should allow Wego to harness MBC’s

various digital platforms to reach millions of local customers using video content and

product merchandising. With significant consolidation in the global travel search engine

market as dominant players such as Expedia and Priceline spread their weight, MBC’s

investment shows confidence in a service that caters to local tastes.

28

“PayTabs raise $20M investment,” ArabNet, August 22, 2017, news.arabnet.me.

29

“Wego,” Case studies, Google Developers, accessed September 2017, developers.google.com.

30

Martin Cowen, “Middle East media giant invests in Wego,” Tnooz, August 7, 2017, tnooz.com.

19Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

20

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

21Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

4. The MENA venture capital ecosystem

to support entrepreneurship is

flourishing

The VC investment ecosystem in MENA is thriving. Incumbent VCs have ramped up activity,

while new VCs have emerged from both within and outside the region. We estimate the

total number of VC-like investors in MENA grew from just nine in 2008 to 145 by the end of

2016.

31

Of these investors, significant classes include regional and international VCs actively

investing in the region, as well as accelerators, incubators, and angel investors (Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7:

MENA incubators, accelerators and co-working spaces

(illustrative and non-exhaustive)

Egypt Morocco

Saudi Arabia Lebanon JordanKuwait

NOT EXHAUSTIVE

SOURCE: Venture Capital in the Middle East, MENAScapes.com

UAE

Bahrain Qatar Tunisia

As the number of investors increases, of course, so too does capital access for entrepreneurs

and early-stage companies. Indeed, total funding in the region has increased significantly,

from $53 million in 2014 to $410 million in 2017 (Exhibit 8),

32

as investors such as Middle

East Venture Partners (MEVP), STC Ventures, Turn 8, and Wamda Capital have raised

significantly sized funds. The number of deals doubled, from 131 in 2014 to 258 in 2017, and

average ticket size also increased, at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 54 percent

from 2014 to 2017.

31

The state of digital investments in MENA: 2013–2016, published 2017, a joint report from arabnet and Dubai

SME, sme.ae.

32

Note: Deals sourced by Careem and SOUQ have been excluded from the data because they disproportionately

skew the figures, with deal sizes of $275 million and $350 million, respectively.

22

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

Exhibit 8:

Funding growth between 2014-2017

Increase in access to funding from

2014

to 2017

Average ticket size,

excluding Souq.com and Careem

1

560

270

138

260

177

191

133

2014

909

2015 2016 2017

Funding ($mn)

No. of deals

CAGR

2

54%

0.43 $mn 1.11 $mn 1.43 $mn

2014 2015 2016

1.59 $mn

2017

1

1 deal per year assumed for both SOUQ and Careem

2

Compound annual growth rate

SOURCE: MAGNiTT analysis and publicly available information

These additional investments are generating outsized returns for investors. Souq.com,

the region’s largest e-commerce player (which was recently acquired by Amazon for $650

million), generated a return of more than 50 percent for its consortium of international

and local investors—including Baillie Gifford, IFC Venture Capital Group, MENA Venture

Investments, and Tiger Global Management—despite a lower valuation relative to its

previous round.

33

The acquisition also brought several strategic advantages to the region

such as an established logistics and fulfillment service and a full-fledged, operational

payments platform.

4.1 Corporate venture capital is becoming increasingly relevant

While VCs in general are proliferating, CVCs in particular are rapidly emerging in the

evolving MENA investment ecosystem. CVCs take diverse forms; they can be anything

from “outsourced R&D departments” to investment vehicles nearly indistinguishable

from a traditional VC. Interestingly, the CVC structure seems especially suited to MENA’s

nuances. The competitive advantage for CVCs relative to their VC counterparts is typically

their ability to leverage parent company synergies and scale in attracting and growing

the most promising start-ups. CVCs can offer start-ups key value-added advantages, from

operational support and customer and distribution access to fast-tracked exit options. In a

start-up ecosystem still disadvantaged by typical emerging market shortfalls, CVCs’ value

proposition of rapidly scaling new ventures can be attractive for budding entrepreneurs.

33

“Souq.com raises more than AED 1 billion (USD 275 million), the largest e-commerce funding in the Middle

East history,” Souq, February 29, 2016, pr.souq.com; Ingrid Lunden and John Russell, “Amazon to acquire

Souq, a Middle East clone once valued at $1B, for $650M,” TechCrunch, March 23, 2017, techcrunch.com.

234. The MENA venture capital ecosystem to support entrepreneurship is flourishing

34

“Careem raises US$ 60 million in new funding with The Abraaj Group as lead investor,” The Abraaj Goup,

November 10, 2015, abraaj.com.

And indeed, in 2015 and 2016, 12 new CVCs entered the MENA market (Exhibit 9). Notably,

Saudi Telecom’s STC Ventures was among the largest external investors in ride-hailing

unicorn Careem, especially in the Seed, Series B, and Series C rounds.

34

Exhibit 9:

Investors in MENA are increasing

Investor growth in MENA, number of investors

12

19

26

10

9

15

13

9

11

18

30

44

65

83

145

30

10

20

0

60

50

40

80

70

100

90

150

110

140

130

120

2009

11

11

2008

1

20132012

2

4

2015

115

2016

6

6

2014

5

2011

6

2010

New noncorporate VCs

Total VC-type investors (estimate)

New corporate VCs

SOURCE: State of Digital investment in MENA – Arabnet

1 Jan 2017

Accordingly, corporate VC AUM grew by more than 660 percent from 2012 to 2017, reaching

one-fifth of total MENA VC AUM (Exhibit 10). The lion’s share of that growth came from

2016 to 2017, and we expect CVC funding to further increase in 2018 and beyond, given

average ticket size in 2017 for CVCs was $29 million—more than double the average in 2016.

CVCs are clearly expressing heightened interest in MENA start-ups.

24

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

Exhibit 10:

CVC growth in MENA

Corporate venture capital (CVC), $bn

0

0.8

1.0

0.4

0.6

1.4

1.2

0.2

0.23

0.26

1613

0.18

0.59

11 2017

1.35

12

+663%

0.04

05

0.10

0.08

2003 04 08

0.45

0.11

0.42

1007

0.05

06 09

0.14

0.15

14 15

0.05

As a % of

total VC

26 32 23 24 11 10 13 16 44 22 25 23 31 29

Number

of deals

4 10 7 13 8 12 9 14 22 23 37 28 46 52

Avg CVC

deal ($mn)

9.83 11.36 13.20 11.56 7.66 13.94 16.60 13.93 23.82 11.08 7.34 11.70 12.24 12.14

20

55

29.40

SOURCE: Pitchbook

4.2 Government-led initiatives are focusing on ecosystem growth

Augmenting the private sector’s increasing involvement in MENA start-ups, government-

led efforts to catalyze digital entrepreneurial growth have emerged across the region. From

targeted, VC-like investment funds to structured incubator and accelerator programs,

public institutions are playing an increasingly key role in the start-up ecosystem. Examples

include:

UAE: Fintech Hive at DIFC, Abu Dhabi Global Markets RegLab.

Saudi Arabia: The government has set aside SAR 2.8 billion in public sector stimulus for

a government VC to support angel investors and private-sector VC funds. Furthermore,

the sovereign wealth fund has a fund-of-funds that will invest in VC and PE, and

the government has created an SME authority with a mandate to develop the whole

entrepreneurship and SME ecosystem beyond just financing—for example, improving

ease of doing business, demand stimulation, business support, innovation, culture, and

education.

Egypt: Fintech Factory by Payfort.

Morocco: Morocco’s capital of Rabat is home to several start-up spaces. The government

has launched programs to support organizations and incubators aimed at promoting

social entrepreneurship, and it has succeeded in improving the creation of social

enterprises.

Kuwait: National Fund for SME Development.

25

Bahrain: home to a Fintech VC fund and accelerator, with a specific Regulatory sandbox

and tailored licenses for fintechs.

Jordan: The Central Bank of Jordan and the World Bank have partnered to launch the

Innovative Startups Fund, which will pool US $98 million in early-stage financing for

innovative start-ups and SMEs with high growth potential.

35

Lebanon: Central Bank of Lebanon start-up fund.

Tunisia: The “Startup Act” is a draft law to encourage the establishment of a new legal

framework and an ecosystem conducive to the emergence of innovative start-ups.

The UAE, currently ranked 26th in the Global Entrepreneurship Index,

36

has been a MENA

pioneer in its start-up ecosystem development efforts (Exhibit 11). New initiatives with

innovative value creation theses, such as the Dubai Future Accelerators, harness public-

and private-sector staff, expertise, and mentors to help companies from around the world

address local opportunities in a variety of digital sectors, without any requirements for

a financial stake. Participating start-ups have seen great successes—with 64 percent of

companies progressing to later-stage investments.

37

Exhibit 11:

UAE efforts

Support organization Business ecosystem Funding source Incubator & hub

Corporate program Government program University program

Coworking space

Event

Technology ecosystem

Media

Domain legend

ILLUSTRATIVE

1999 2002 2005 2007 2006 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Impact Hub Dubai

Dubai

Biotechnology and

Research Park

Inj az UAE

Began allowing

publication of company

records at Department

of Economic

Development

Abolished requirement

for severanc e

payments

Twofour54 in

Abu Dhabi

Improved online system for

obtaining no objection

certificates and building

permits

Abolished minimum capital

requirement and simplified

documentation

requirements for registration

Masdar City Free Zone

Increased capacity at

container terminal in Dubai,

eliminated requirement for

handling receipt

HoneyBee Tech Ventures

in Dubai

MBC Ventures

BECO Capital

The Entrepreneur

TV show

Y Venture Partners

in Beruit

Turn6

Introduced disclosure requirements

to relate d-party transactions in

annual stock exchange report

Increased operating hours of land

registry and reduced transfer tees

Eliminated site inspections and

reduced time required to provide

new connections

Flat6Labs Abu Dhabi

Dubai Future Accelerators Initiative

Announced 1.8 million sq. ft.

Innovation Hub

Law on declaration of bankruptcy

Dubai SME and Al Tamimi &

Company j oin to support

entrepreneurial innovations and

patents

Dubai's Global Blockchain Council,

public-private initiative

Mohammad bin Rashid Al

Maktoum Innovation Fund

SME Beyond Borders and similar

conferences

Dubai Internet City

Established in private

credit bureau and

allowed borrowers to

inspect data in bureau

Introduced electronic

filing for court documents

Jabbar Internet Group

Investors MENA

Created legal framework for

operation of private credit bureau

Streamlined document

preparation and reduced time to

trade with launch of new customs

system

Dubai SME

SeedStartup

Created law to establish federal

credit bureau under supervision

of central bank

Merged filing documents with

Chamber of Commerce and

Department for Economic

Development

Removed the requirements for English and

Arabic headboards after receiving office

premise clearance

Established an online filing and payment

system for social security contributions

WOMENA

Created a “one window, one step” process

to submit and track documents online

Emerge Ventures

Potential—Hadafi, free women’s

entrepreneurship program

In5, three innovation centers for

entrepreneurs and start-ups

NYU Abu Dhabi Hackathon

Endeavor UAE

Dubai SME, Higher

College of Technology

Incubator

AstroLabs, Dubai Tech

Hub

Dubai Technology

Entrepreneurship

Centre

Mohammed bin Rashid Al

Maktoum Foundation

Khalifa Fund

SOURCE: Wamda Research Lab’s Country Insight 2015, Venture capital in the Middle East, MENAScape

35

Dana Al Emam, “Planning ministry, World Bank sign loan agreement to establish Innovative Startups Fund,”

The Jordan Times, August 21, 2017, jordantimes.com.

36

Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018, The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute, 2018,

thegedi.org.

37

“Dubai future accelerators invests in 19 projects graduating first session of the program,” Entrepreneur,

December 21, 2016, entrepreneur.com.

4. The MENA venture capital ecosystem to support entrepreneurship is flourishing

26

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

Saudi Arabia’s government has similarly committed to significant investments both

globally, through the Vision Fund, as well as through other entities like the SMEA. The

joint effort by Japan’s SoftBank Group and Saudi Arabia’ PIF has created the world’s largest

fund (with more than $93 billion raised to date), to invest in technology sectors including

emerging tech such as artificial intelligence and robotics.

38

The Central Bank of Lebanon has launched multiple initiatives, including the setup of

EntrepreneursLebanon.com. This central online platform provides multiple services,

including entrepreneur collaboration spaces, connections with investors and funders,

information on support organizations, and a calendar listing local and regional

entrepreneurship-focused events. The Central bank promises $400 million worth of

investment in the knowledge economy, of which $200 million is a recent new commitment to

help guarantee Lebanese commercial banks’ direct investments in local start-ups or

VC funds.

39

4.3 Exits are a key challenge in the region

Over 2012-2017, 60 MENA start-ups have exited at an estimated valuation of approximately

$3 billion in aggregate.

40

However, the majority of exits in the region are strategic exits—

direct equity sales to large, family-owned groups or multinational companies. The

predominant exit valuation for over one-third of the region’s exits was between $10 million

and $20 million.

41

Overall, more than 60 percent of the disclosed deals were for less than $50

million.

42

Some notable examples were Amazon’s acquisition of MENA-focused Souq.com;

43

Alabbar Enterprises’ purchase of the UAE’s JadoPado;

44

Delivery Hero’s trio of acquisitions,

including Turkey’s Yemeksepeti, as well as Kuwaiti food delivery companies Talabat and

Carriage;

45

Tiger Global Management’s acquisition of the daily deals website Cobone.

com;

46

Thomson Reuters’ purchase of the business information portal Zawya;

47

and Japan’s

Cookpad taking over the Lebanese recipe website Shahiya.

48

In contrast, public listings, or IPO exit opportunities, are limited in the region. Of the more

than 1,000 IPOs around the world in 2016, less than 10 percent were on exchanges in the

38

Andrew Torchia, “Softbank-Saudi tech fund becomes world’s biggest with $93 billion of capital,” Reuters, May

20, 2017, reuters.com.

39

Chloe Domat, “Lebanon’s Central Bank pledges $600 million for start-ups,” Global Finance, October 14, 2016,

gfmag.com.

40

Magnitt News, “Startup fever: MENA exits reach $3 billion over five years,” June 21, 2017, magnitt.com.

41

Magnitt News, “Startup fever.”

42

Magnitt News, “Startup fever.”

43

Simeon Kerr, “Amazon to acquire Middle Eastern online retailer Souq.com,” Financial Times, March 22, 2017,

ft.com.

44

“Fund led by Dubai billionaire Alabbar buys UAE website JadoPado,” Reuters, May 11, 2017, reuters.com.

45

Ingrid Lunden, “Delivery Hero eats up Turkey’s Yemeksepeti for a record $589M,” Tech Crunch, May 5,

2015, techcrunch.com; Shona Ghosh, “Food ordering startup Delivery Hero is buying Kuwaiti rival Carriage,”

Business Insider, May 30, 2017, businessinsider.com.

46

Triska Hamid, “Daily deal website Cobone has new owner,” National, December 7, 2014, thenational.ae.

Note: Cobone has since been purchased from Tiger Global Management by Middle East Digital Group for an

undisclosed amount.

47

Frank Kane, “Thomson Reuters buys business information service Zawya,” National, June 26, 2012,

thenational.ae.

48

“Japan’s Cookpad to acquire Middle East recipe purveyor,” Nikkei Asian Review, October 30, 2014, asia.nikkei.

com.

27

Middle East.

49

Across MENA, the IPO market readiness is low relative to more developed

markets, lacking depth and maturity.

Varying factors impact the IPO readiness, such as regulatory hurdles, types of institutional

investors involved, valuation potential, exchange listing standards, and fees. Regulatory

readiness remains a critical hurdle to be overcome in MENA, where currently highly

complex procedures and high tax rates involved in exits act as a major deterrent to the

process. One common example is the 20 percent capital gains tax imposed in Saudi Arabia

on foreign parties exiting their shares in unlisted companies.

50

Moreover, a lack of uniform

transparency and disclosure hinders overall start-up investment in every stage,

especially exits.

49

Global IPO trends: Q2 2017 Investor confidence is growing, Ernst & Young, 2017, ey.com.

50

10th Annual MENA Private Equity and Venture Capital Report 2015, a joint report with Deloitte, Dubai

International Finance Centre, MENA Private Equity Association, and Thomson Reuters, 2015, menapea.com.

4. The MENA venture capital ecosystem to support entrepreneurship is flourishing

28

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

29Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

5. Six best practices for start-up

ecosystems players to turbo-charge

MENA entrepreneurship

Overall, the ecosystem supporting the growth of MENA’s digital entrepreneurship potential

has been falling into place, with thriving demand, bolder entrepreneurs, proliferating VC

firms, and increased government enablement. However, to unlock all its entrepreneurship

potential, we recommend that all public and private investors—including VCs, CVCs, family

offices, public entities, and so forth—adopt six best practices.

5.1 Develop robust investment theses leveraging local context

The first of the core elements essential to succeeding in emerging entrepreneurial

ecosystems is to craft investment theses that provide a disproportionate ability to create

value. Investment theses will guide investors and entrepreneurs in their investment

decisions and allow local investors to establish their goals in the MENA context. The

right thesis not only capitalizes on the investor’s distinctive value proposition (aside from

capital), but also helps attract the right investment talent and LPs. Four prominent types

of theses include insight-driven, vertical-driven, asset/capability-driven, and geographic-

driven (Exhibit 12). Each is borne of a different set of beliefs.

Exhibit 12:

Types of investment theses (outside-in view)

Types of investment theses Examples

VC believes it has insight on how

start-up space will evolve and

where future value will be

created

Insight-

driven

Union Square Ventures looks for network effects:

"

Large networks of engaged users, differentiated

through user experience, and defensible through

network effects

.”

VC believes in growth of a

specific vertical and therefore

hires top investment minds in

specific vertical

Vertical-

driven

Deep Space Ventures focuses on eSports: “

how big

[eSports] market is… how early we are in the

evolution of the market, how fast it is growing, and

how intensely passionate the individuals who

comprise this market are about playing, improving,

and following the space.

”

VC invests where it can add

disproportionate value from its

own assets or portfolio, or the

start-up can add disproportionate

value to investor's portfolio.

Typical of CVCs.

Asset/

capability-

driven

Intel Capital invests in start-ups with strong core

value:

“…focus on investing more money in fewer start-

ups that are strategically aligned with the company's

lines of business, moving away from chasing

opportunities based solely on their financial returns..”

Geo-

graphic-

driven

VC invests in geography it

believes is under-invested in

and holds much promise. Typical

of emerging market VCs.

SAIF Partners focuses on India:

“

The $350 million fund… was now focused only on

the home country and its buzzing start-up

ecosystem.

”

SOURCE: Deal Street Asia, Intel Capital, Deep Space Ventures, Union Square Ventures

5.2 Capture and proactively engineer network effects

The start-up investment landscape reveals the power law distribution in practice: returns

are concentrated in a select cadre of start-ups. For that reason, co-investing with other funds

can allow for a healthy pipeline of deals while minimizing downside risk associated with the

seed level given that investments are diversified across a larger number of potentials hits

(and misses).

30

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

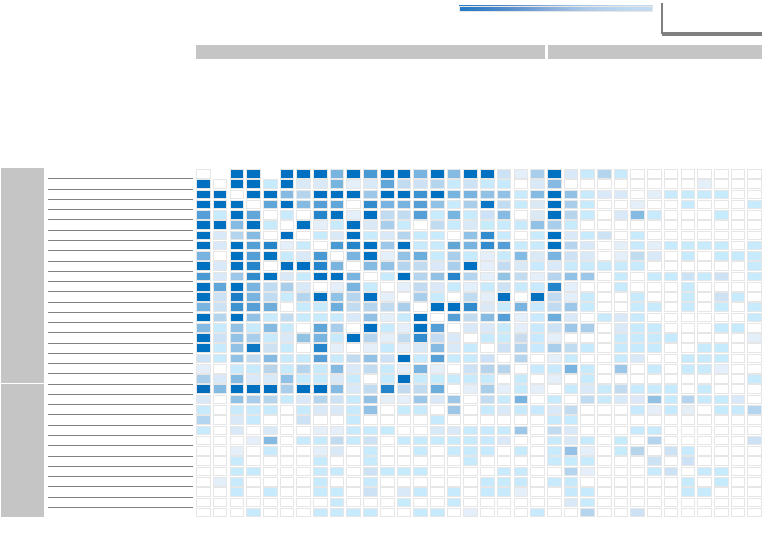

In Silicon Valley, for instance, larger-scale, top-performing VC firms tend to have higher

levels of deal syndication than single-investor CVC firms (Exhibit 13). Accordingly, these

network effects likely lead to significantly higher deal flow—that is, more business proposals

and investment offers. Investors across MENA can adopt a similar approach, overcoming

structural gaps in the current landscape by putting additional effort in maintaining a broad

and diverse set of deal partners.

Exhibit 13:

Top performing VCs have significantly higher deal syndication – broad deal flow is

critical to success

VC firms

Corporate

investors

Lerer Hippeau Ventures

Andreessen Horowitz

First Round Capital

Kleiner Perkins Caufield &

Byers

Founder Collective

500 Startups

Greylock Partners

New Enterprise Associates

Felicis Ventures

Accel

CrunchFund

Index Ventures

Khosla Ventures

General Catalyst Partners

Sequoia Capital

Founders Fund

CRV

Redpoint Ventures

Bessemer Venture Partners

Union Square Ventures

GV

Intel Capital

Qualcomm Ventures

DG Incubation

Salesforce Ventures

Comcast Ventures

Cisco Investments

In-Q-Tel

Samsung Ventures

Bertelsmann Digital Media Inv

T-Venture

Motorola Solutions

SV Angel

American Express

VC firms Corporate investors

Lerer Hippeau Ventures

Andreessen Horowitz

First Round Capital

Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers

Founder Collective

500 Startups

Greylock Partners

New Enterprise Associates

Felicis Ventures

Accel

CrunchFund

Index Ventures

Khosla Ventures

General Catalyst Partners

Sequoia Capital

Founders Fund

CRV

Redpoint Ventures

Bessemer Venture Partners

SV Angel

Union Square Ventures

Intel Capital

Qualcomm Ventures

DG Incubation

Salesforce Ventures

Comcast Ventures

Cisco Investments

In-Q-Tel

Samsung Ventures

Bertelsmann Digital Media Investments

T-Venture

Motorola Solutions

GV

American Express

EXAMPLE:

SILICON VALLEY

Amount of deals shared between VCs.

Darker square = more shared deals

SOURCE: CBInsights, cbinsights.com

In addition, for investors, the benefits of network effects extend beyond deal flow

syndication. As generations of start-ups graduate from seed to revenue-generating growth

ventures, they become active and passive assets within their networks. In leading global

accelerator Y Combinator, for example, program graduates become mentors to later cohorts

of aspiring founders.

To date, a limited number of public and private players in the MENA ecosystem have engaged

in network engineering. In Saudi Arabia and the UAE, some government initiatives and

programs have connected all stages of the start-up life cycle, from support to innovation

and seed-stage, to early-stage incubators and accelerators, to revenue-generating and SME

development programs. In the VC space, some entities have similarly taken a multistage

approach to partnerships with other entities, building deal flow ranging from seed and

early-stage through active VC investing on later-stage ventures. For example, Flat6Labs and

Sawari Ventures have maintained a portfolio of investments across these stages to engineer

their own microecosystem.

315. Six best practices for start-up ecosystems players to turbo-charge MENA entrepreneurship

5.3 Invest at scale

The capital managed by the ten largest US VC firms has doubled over the past decade,

bringing myriad advantages. Economies of scale within a fund can be leveraged to acquire

and retain better talent, as well as to expand a quality network with strong links between VC

general partners and entrepreneurs to boost quality deal flow and exploit synergies within

the portfolio or parent company.

As a result, such scale has led to the largest funds generating top-quartile internal rate of

return (IRR) performance relative to smaller funds. Over the past several decades, the top 5

percent of US VC firms by measure of AUM have, on average, been more than twice as likely

to be top performers relative to the smallest 75 percent of US funds by AUM (Exhibit 14).

Exhibit 14:

Frequency of top quartile performance

0

80

60

40

20

Fund vintage

2005–08

Frequency of top-quartile performance among US VC firms, %

1980–84 1985–89 2000–041990–94 1995–99

Largest 5% of funds in each vintage

Smallest 75% of funds in each vintage

SOURCE: ThompsonOne, Fortune, US NBER, Preqin

Indeed, a breakdown of US VC funds by AUM further reveals the IRR performance gap

enjoyed by the top 5 percent (Exhibit 15). While funds in the three smallest quartiles

performed in the top quartile less than a quarter of the time, the largest quartile of US VC

funds by AUM exhibited disproportionate top-quartile IRR performance of 32 percent.

Narrowing down to the top 5 percent of US VC firms by AUM, an impressive 41 percent of the

largest firms exhibited top-quartile IRR performance.

32

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

Exhibit 15:

Proportion of funds in each size category falling into each IRR performance quartile

27%

28%

29%

16%

26% 24%

28%

23%

20%

25%

25%

21%

29%

30%

22%

23%

23%

32%

41%

10%

Largest 5%

of funds in

each vintage

Largest 25%

of funds in

each vintage

3rd fund

size quartile

2nd fund

size quartile

Smallest 25%

of funds in

each vintage

2nd quartile 4th quartile

3rd quartileTop quartile

Performance quartile

1

SOURCE: Thomson ONE

1

Figures may not sum to 100%, because of rounding

Investors across MENA must integrate this key lesson: investing with scale is more likely to

sustainably yield significant returns in the long run.

5.4 Invest and manage performance with a patient, programmatic growth mind-set

Too often, traditional VC investors take a short-term approach to IRR expectations.

Adjusting the typical investment horizon from short-term earnings to medium and longer-

term gains will require a shift in mind-set in the region’s ecosystem players, especially

public investors and CVCs. Typically, CVCs face annual and quarterly targets, whereas VC

return horizons are much longer (8–12 years). Growth without discipline can lead to bloated

portfolios that lack focus and the ability to adapt rapidly to shifts, such as technological

advances and contextual changes in the region.

Instead, performance should be managed by setting and monitoring investment progress

against specific key performance indicators (KPIs) that address strategic, operational, and

cultural issues.

The approach of four large Chinese firms to investing in US technology companies has

demonstrated that a patient, disciplined, and programmatic strategy can create significant

value in the medium to long term. From 2011 to 2017, these four Chinese firms increased

their investments into US tech companies at a CAGR of 24 percent (Exhibit 16). The more

than 800 deals involved $8 billion in focused capital.

33

Exhibit 16:

The number of Chinese-backed deals from 2011 to 2017 had a CAGR of 24 percent

137

193

172

138

77

59

37

2013 2014

+24% p.a.

2016 2017201520122011

Chinese-backed deals into US tech companies, # of deals by year

SOURCE: PitchBook

5.5 Secure investment independence in governance, to win right talent

It’s crucial for VC firms to separate core business KPIs and earning expectations from VC

investments. CVCs, in particular, often find it difficult to find the right governance balance.

On the one hand, CVCs need to let the start-ups and VCs operate with enough independence

to move rapidly. On the other hand, a system has to be in place to ensure that the investments

made align with the strategic objectives of the parent. In addition, the metrics used for start-

ups (adoption, traction, etc.) are significantly different from usual financial metrics adopted

by corporate investors.

Getting governance right is critical and requires balancing between two equally important

objectives: ensuring the independence of investors while aligning them with the cause,

and maintaining an independent investing body allocating capital independently of the

investors who contribute funds. Firms’ widespread use of the “2+20” fee (that is, 2 percent

of total asset value and 20 percent of any profits earned) and carry incentive schemes

underlie these governance models—focusing incentives on variable, performance-based

compensation to ensure general partners are focused first on generating returns.

VC talent is rare, and it requires much different talent acquisition, retention, and

performance management / compensation methods. These may not automatically align

with corporates existing setups and getting the governance right to attract the right talent

requires a concerted effort. MENA investors must bear this in mind as they optimize for

getting governance right.

5. Six best practices for start-up ecosystems players to turbo-charge MENA entrepreneurship

34

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth

5.6 Monitor KPIs in line with value creation model

From the onset, VCs need to consider what KPIs to track for the investment made. Typical

VCs are usually financially driven by IRR or cash in simple terms. However, some theses-

driven VCs should have a strategic KPI to facilitate investing in a particular start-up, be it

exposure to a certain sector or stage of funding.

In general, CVCs have a much broader set of KPIs than other investors (Exhibit 18). In

addition to pure financials, CVCs factor in whether and how a potential investment ties in

with their overall strategic vision. For instance, what synergies can the parent company

drive in terms of complementing products? How can it help mitigate risks via industry

diversification? How can it help be a disruptive innovator? Another traditional CVC KPI

relates to the organizational impact of an investment. How can the employees of both

companies interact with each other? Is there a way to facilitate technology and knowledge

transfer between them? How can a parent gain from the faster pace innovation timelines of a

start-up so that it become more agile?

Exhibit 17:

Typical VC, CVC KPIs

Financially focused CVC & VC Core-driven CVC

Organizational

▪ N/A

▪ Knowledge (ie, integrate technology and market

knowledge into core)

▪ Employee engagement (eg, involvement in cross-

unit activities)

▪ Corporate innovation (eg, new initiatives, products

and features, R&D, etc)

Strategic

▪ Proportion of deals in line with

sector/stage investment thesis

▪ Strategic moves (complementary products,

services, market/segments access, operational

improvement)

▪ Network expansion (build and use partner

network, start-up ecosystem)

▪ Risk mitigation (industry diversification and

strategic hedging vs disruption)

Financial

▪ Internal rate of return (IRR)

▪ Cash-on-cash returns

▪ Net asset value

▪ Internal rate of return (IRR)

▪ Cash-on-cash returns

▪ Post-acquisition ROE

35

36

Given MENA’s strengthening digital presence; demographic shifts toward a younger, tech-

savvy population; and the exponential evolution of technology, digital consumption in the

MENA region is growing exponentially. However, the digital entrepreneurship landscape

has remained limited, as the bulk of the region’s digital potential is not being tapped and exit

options are limited for start-ups that have ventured into the digital space. Furthermore,

competition from foreign players is eating up a major chunk of the market.

That said, we are in the midst of an uplift of digital entrepreneurship in MENA, with visible

acceleration in the number of start-ups and funding opportunities, especially through

CVCs. However, the coming of age of entrepreneurship in the MENA region will hinge on

the right enabling environment to support investor financing, growth, and value creation.

To unlock the start-up system, private and public investors must play an active role and take

deliberate and concerted actions regarding investment theses, networking, growth mind-

set, investment scale, governance and performance management. The best practices offered

in this article are just the beginning—but they form a crucial foundation for the future of

investment in MENA entrepreneurship.

6. Conclusion

Entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: How investors can support and enable growth 37

About the authors

Omar El Hamamsy is a senior partner in McKinsey’s Dubai

office. He leads much of the firm’s work in technology and media

in the Middle East and broader region, as well as co-leads the

firm’s entrepreneurship efforts in the Middle East.

Abdur-Rahim Syed is a partner in McKinsey’s Dubai office.

He is part of the Telecom, Media & Technology practice, as well

as Digital McKinsey. He co-leads McKinsey’s entrepreneurship

practice in the Middle East.

Luay Khoury is an associate partner in McKinsey’s Dubai office.

He is part of the Telecom, Media & Technology practice, and

co-leads McKinsey’s Advanced Analytics service line in the

Middle East.

Ahmad J. Alkasmi is an associate in McKinsey’s Dubai office,

and specializes in innovation and entrepreneurship topics across

the Middle East and North America.

The authors would also like to acknowledge Rauf Khan, Bilal

Tariq, and Katherine Verrier-Fréchette for their contributions.

Contacts

Omar El Hamamsy

Omar_El_Hamamsy@mckinsey.com

Abdur-Rahim Syed

Abdur-Rahim_Syed@mckinsey.com

Digital McKinsey

03.04.18

Copyright © McKinsey & Company

www.mckinsey.com